Triterpenoid bis-Amide Analogs via the Ugi Reaction †

Abstract

1. Introduction

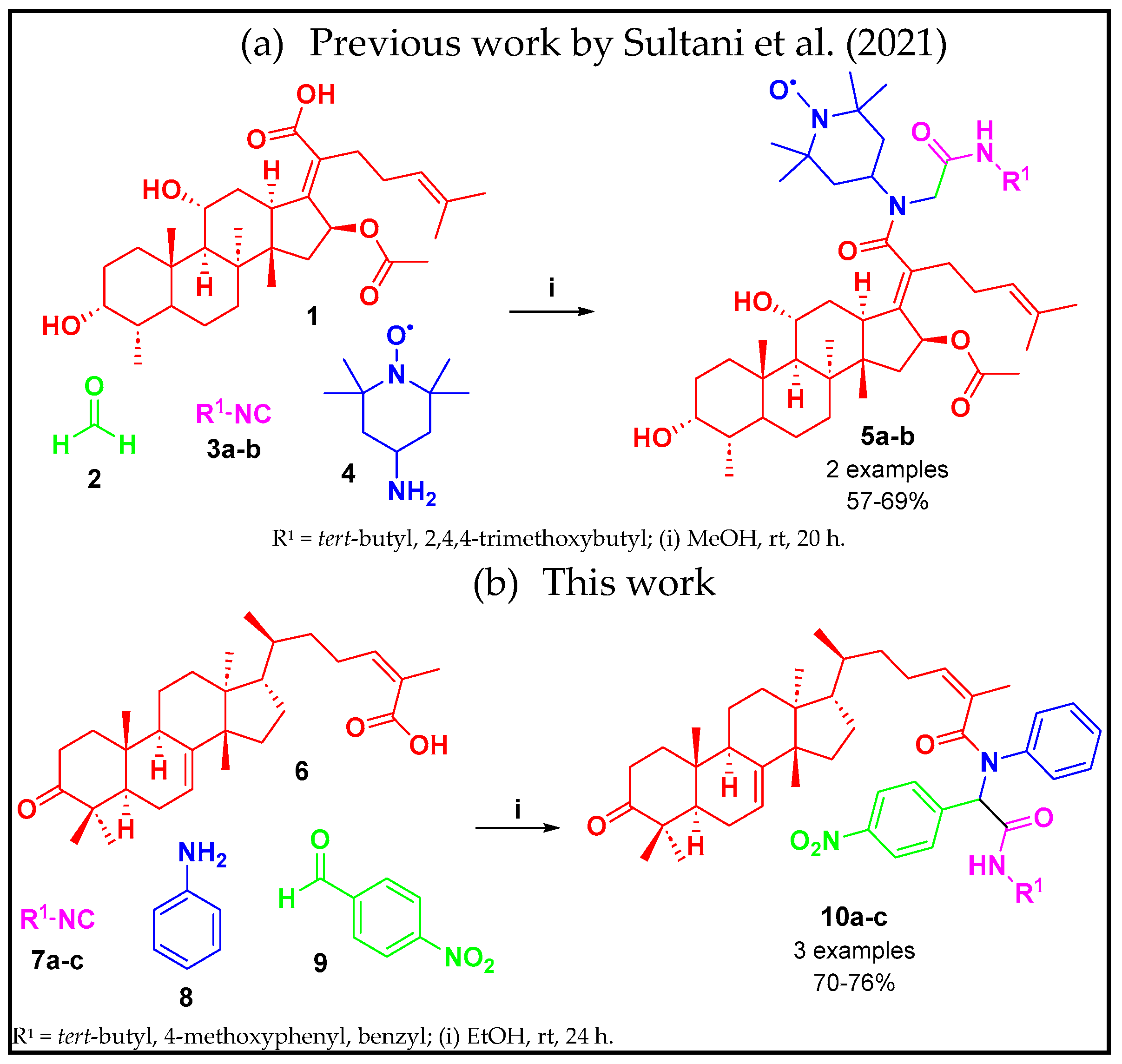

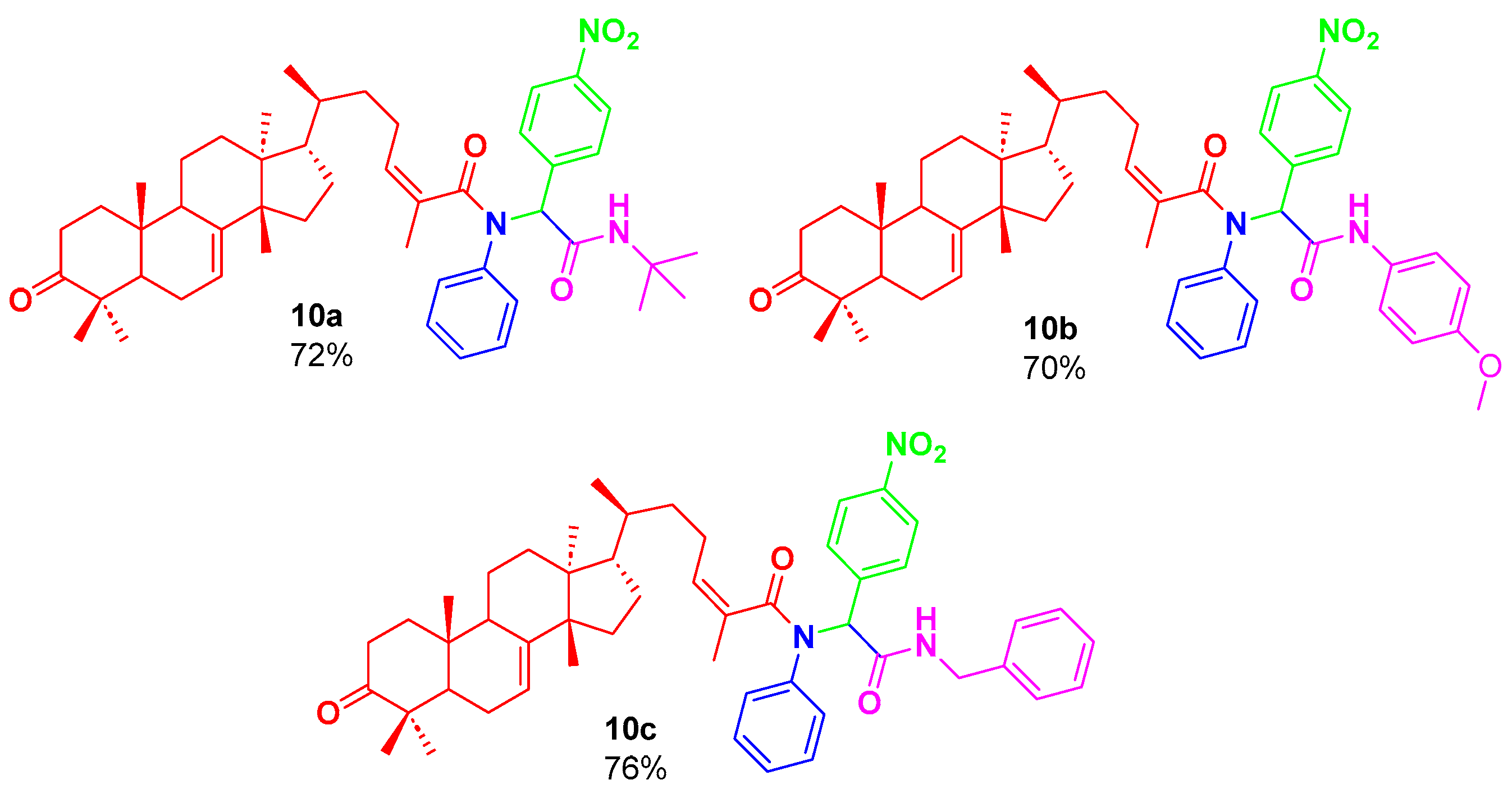

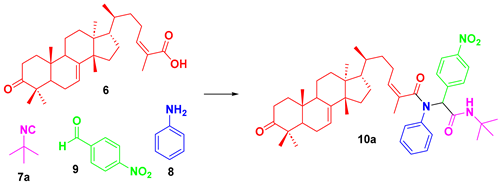

2. Results and Discussion

3. Experimental Section

3.1. General Information, Instrumentation, and Chemicals

3.2. General Procedure

3.3. Spectral Data

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dömling, A.E.; AlQahtani, A.D. General Introduction to MCRs: Past, Present, and Future. In Multicomponent Reactions in Organic Synthesis; Zhu, J., Wang, Q., Wang, M., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tietze, L.F.F.; Brasche, G.; Gericke, K.M. Multicomponent reactions. In Domino Reactions in Organic Synthesis; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cioc, R.C.; Ruijter, E.; Orru, R.V.A. Multicomponent reactions: Advanced tools for sustainable organic synthesis. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 2958–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, M.A.; Abdel-Hamid, H.; Ayoup, M.S. Two Decades of Recent Advances of Ugi Reactions: Synthetic and Pharmaceutical Applications. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 42644–42681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudick, J.G.G.; Shaabani, S.; Dömling, A. Isocyanide-based multicomponent reactions. Front. Chem. 2020, 7, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reguera, L.; Attorresi, C.I.; Ramírez, J.A.; Rivera, D.G. Steroid Diversification by Multicomponent Reactions. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2019, 15, 1236–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brahmkshatriya, P.P.; Brahmkshatriya, P.S. Terpenes: Chemistry, Biological Role, and Therapeutic Applications. In Natural Products; Ramawat, K., Mérillon, J.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 2665–2691. [Google Scholar]

- Chudzik, M.; Korzonek-Szlacheta, I.; Król, W. Triterpenes as Potentially Cytotoxic Compounds. Molecules 2015, 20, 1610–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiemann, J.; Heller, L.; Csuk, R. An Access to a Library of Novel Triterpene Derivatives with a Promising Pharmacological Potential by Ugi and Passerini Multicomponent Reactions. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 150, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultani, H.N.; Morgan, I.; Hussain, H.; Roos, A.H.; Haeri, H.H.; Kaluđerović, G.N.; Hinderberger, D.; Westermann, B. Access to new cytotoxic triterpene and steroidal acid-TEMPO conjugates by Ugi multicomponent-reactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Solvent | Time | Yield |

| 1 | MeOH | 24 h | 38% |

| 2 | EtOH | 24 h | 72% |

| 3 | H2O | 48 h | NR |

| 4 | H2O (80 °C) | 12 h | traces |

| 5 | Solvent free | 24 h | NR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodriguez-López, F.; Saldana-Arredondo, C.; García-Gutiérrez, H.A.; Gámez-Montaño, R. Triterpenoid bis-Amide Analogs via the Ugi Reaction. Chem. Proc. 2025, 18, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecsoc-29-26852

Rodriguez-López F, Saldana-Arredondo C, García-Gutiérrez HA, Gámez-Montaño R. Triterpenoid bis-Amide Analogs via the Ugi Reaction. Chemistry Proceedings. 2025; 18(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecsoc-29-26852

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodriguez-López, Fidel, Cristian Saldana-Arredondo, Hugo A. García-Gutiérrez, and Rocío Gámez-Montaño. 2025. "Triterpenoid bis-Amide Analogs via the Ugi Reaction" Chemistry Proceedings 18, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecsoc-29-26852

APA StyleRodriguez-López, F., Saldana-Arredondo, C., García-Gutiérrez, H. A., & Gámez-Montaño, R. (2025). Triterpenoid bis-Amide Analogs via the Ugi Reaction. Chemistry Proceedings, 18(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecsoc-29-26852