1. Introduction

India’s agricultural sector at present embodies significant adverse environmental and social externalities. Although the green revolution’s promotion of high-yielding seed varieties and fertilisers did solve the problem of food-grain shortages, its drawbacks are visible in the form of degraded land, soil, and water quality, and farmer indebtedness due to a high dependency on external inputs. On the economic front, India has increased its cereal production tremendously since the 1970s, and now it is the largest producer and exporter [

1]. For instance, wheat and rice production have increased by 310 percent and 160 percent, respectively, whereas Nutri-cereals have experienced a rise of only 45 percent [

2]. The income rise on farms has been the slowest compared to the income rises in other sectors.

The social reality is that although India has become calorie-secure, around 22 percent of India’s adult population (15–49 years) are undernourished, and more than 58 percent of Indian children (up to 5 years) are anaemic [

3]. Cereals have fulfilled calorie needs, but our nutrient needs are still lacking. About 60 percent of farmers dependent on rainfed agriculture [

4] have not been impacted much by the benefits of the green revolution.

Our current production patterns have led to land degradation and desertification, and years of chemical application have reduced the ability of the crops to respond to fertilisers by almost 3.5 times between 1970 and 2005 [

5]. About 78 percent of applied urea still goes into the environment, pollutes groundwater, affects biodiversity, and degrades soil [

5]. These mounting realities make it imperative to look at an alternate approach to agriculture that is more sustainable—economically, socially, and environmentally. Sustainable agriculture could be more remunerative by diversifying crops and lowering input costs. It can be socially more inclusive as it enhances incomes for small farmers and promotes diverse nutrient-rich diets. Environmentally, sustainable agriculture reinforces ecological balance and increases resilience. For example, natural farming fields in Andhra Pradesh have shown resilience during extreme weather events, and integrated pest management (IPM) tactics have helped control locust attacks that are increasingly on the rise.

Thus, this research highlights the state of sustainable agriculture in India by first identifying the most widespread sustainable practices. Second, it assesses them through an agroecological lens; third, it documents the current state of adoption (geographic spread and scale) of these practices among farmers in India; fourth, it aims to understand each of their impacts on the economy and society and environment. Moreover, the study identifies the gaps in the literature and gives direction to prioritise research areas based on the existing impact evidence gaps.

2. Methodology

2.1. Review of Existing Literature

An extensive review of existing literature related to the terms “sustainable agriculture” and “agricultural sustainability” led us to review papers that analysed over 70 different definitions of the concept [

6]. Thirty sustainable practices implemented in the country were identified. Practices focus only on one dimension of agriculture, whereas systems are more holistic that can include several components within. They are collectively referred to as sustainable agricultural practices and systems (SAPSs).

2.2. Applying the FAO’s Agroecological Framework

FAO’s ten agroecology elements [

7] are utilised as an analytical framework or tool to shortlist the practices and systems as it helps to evaluate the social, economic, and environmental impacts in a well-integrated manner. Eight out of the ten agroecological elements were selected to assess the SAPSs shown in

Figure 1. By using a criterion of at least four of the elements set as a benchmark, around 16 practices were selected for in-depth review (

Figure 1).

2.3. Systematic Review of Literature

The evidence for each SAPS was mapped against a few indicators through a systematic review of publications. A literature search strategy was developed to identify and select publications for each SAPS. It involved selecting the search engines, inclusion or exclusion criteria, Boolean/keywords identification, and finalising the publication types. The publication timeline was dated between 2010 and 2020 to keep the literature review manageable and focus on more contemporary evidence. Further, the research scope was limited to the first 75 and 30 publications in the Google Scholar Advanced Search and Google Advanced Search to keep the literature review manageable.

2.4. Primary Survey and Stakeholder Consultations

An online survey was done to identify the key stakeholders, including civil society organisations (CSOs), involved in researching and implementing the various SAPSs. About 180 CSOs and research institutions across 36 states and union territories responded to the online questionnaires. More than 50 stakeholders from government, research, academic institutions and CSOs were consulted who were experts within each SAPS to fill in the study gaps.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. State of Sustainable Agriculture in India

Our findings strengthen the generic understanding that sustainable agriculture in India is on the margins. This is because only five practices have more than 4 percent of the net sown area. Most SAPSs have around 4 percent (less than five million) of adopters implementing them, and less than one percent of the farmers adopt several of these practices.

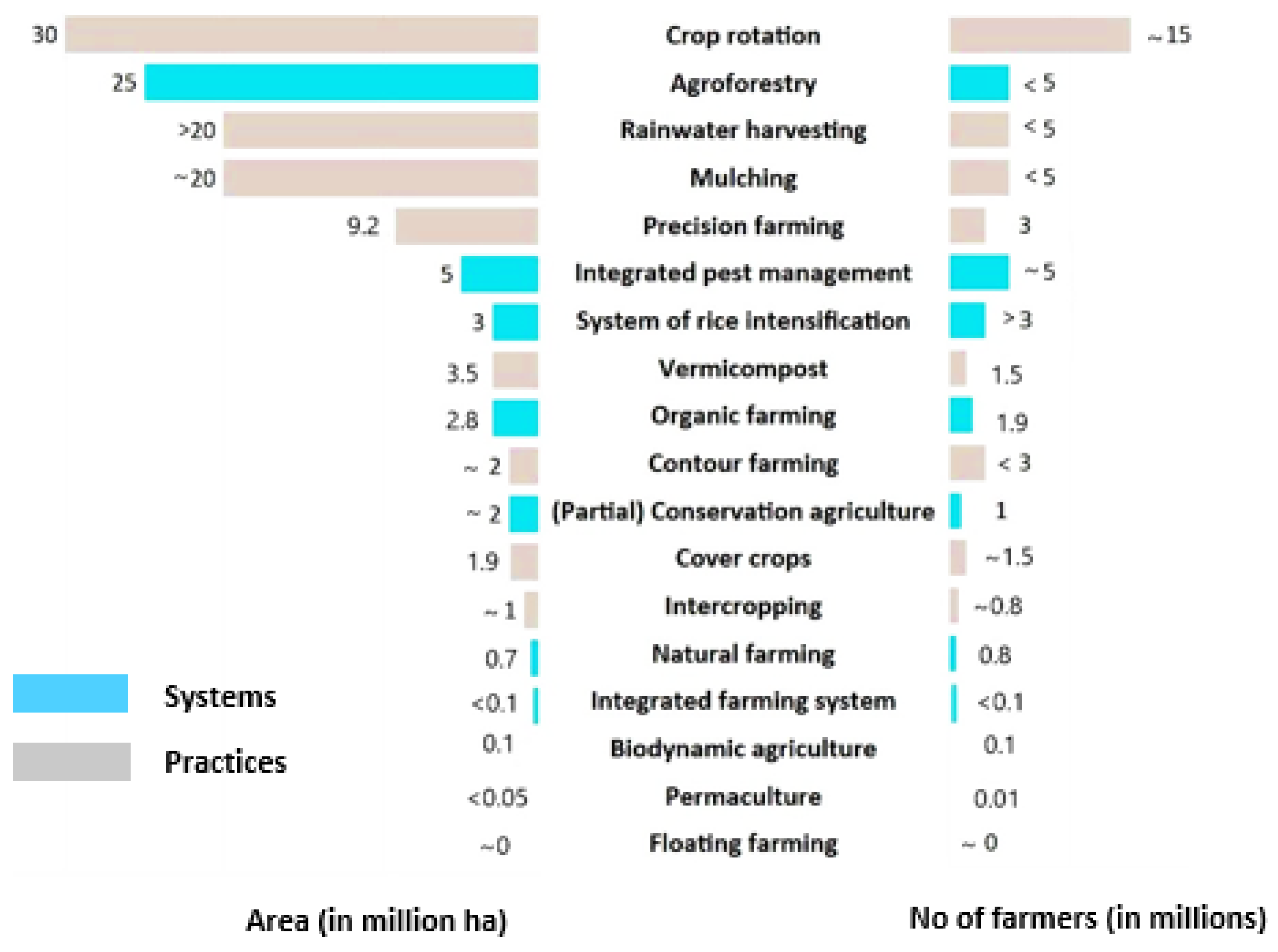

Figure 2 summarises the area and adoption of each SAPS gathered from literature, Stakeholder consultations and estimations thereof.

3.2. Impact Evidence of SAPSs on Outcomes

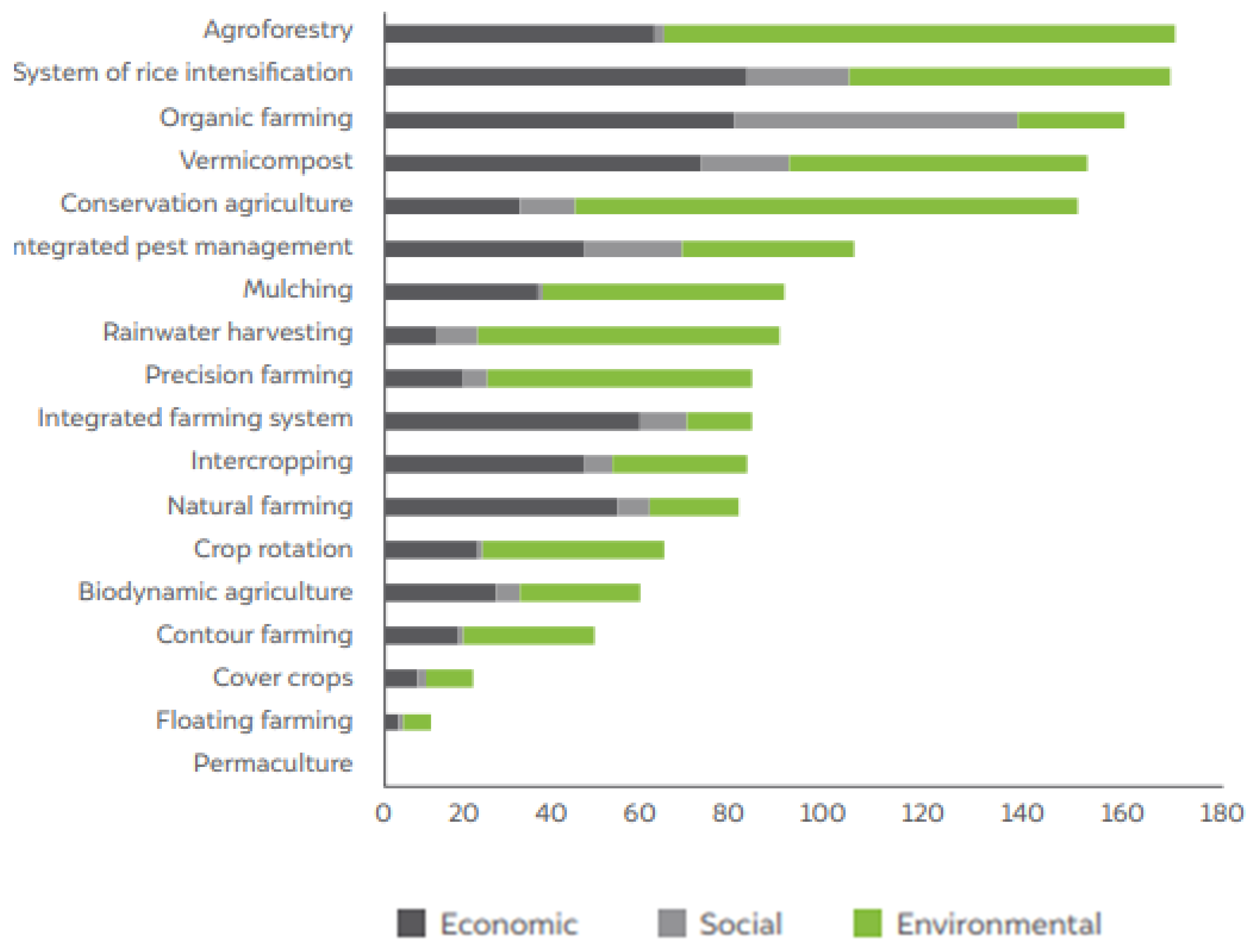

The literature review discloses practices like agroforestry, the system of rice intensification (SRI), and organic farming to be the most researched among the SAPSs based on several indicators (

Figure 3).

The literature for most SAPSs consists of short-term assessments (less than three years) for all indicators, whereas long-term studies are missing. A few exceptions were CA, for which long-term studies mainly concentrated on ecological impact in the Indo-Gangetic regions.

Except for agroforestry, studies conducted at a landscape or an agroecological level were missing for most practices, as they were restricted in large part to plot-level field trials.

In the publication evidence, themes like crop yields, income, water, and soil are more researched, whereas gender and health aspects, emissions, and biodiversity are less explored.

Papers evaluating the impact of SAPSs predominantly tend to focus on a single theme like soil health, water, etc., rather than multidimensional themes.

There are inadequate measurement indicators to measure farm productivity, and conventional methods are often not sufficient. Generally, sustainable practices promote crop and livestock integration; however, evidence for the total farm output is lacking.

3.3. Policy Scenario for Sustainable Agriculture in India

A comprehensive framework in the National Mission of Sustainable Agriculture (NMSA) has existed at the national level since 2014–15, with several components on rainfed areas, water and soil management, and agroforestry [

8]. National Innovations in Climate Resilient Agriculture (NICRA) under the ICAR focuses on CA and SRI. Rainwater harvesting is promoted through the Integrated Watershed Management Programme, and the Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchai Yojana encourages precision irrigation and water-saving methods.

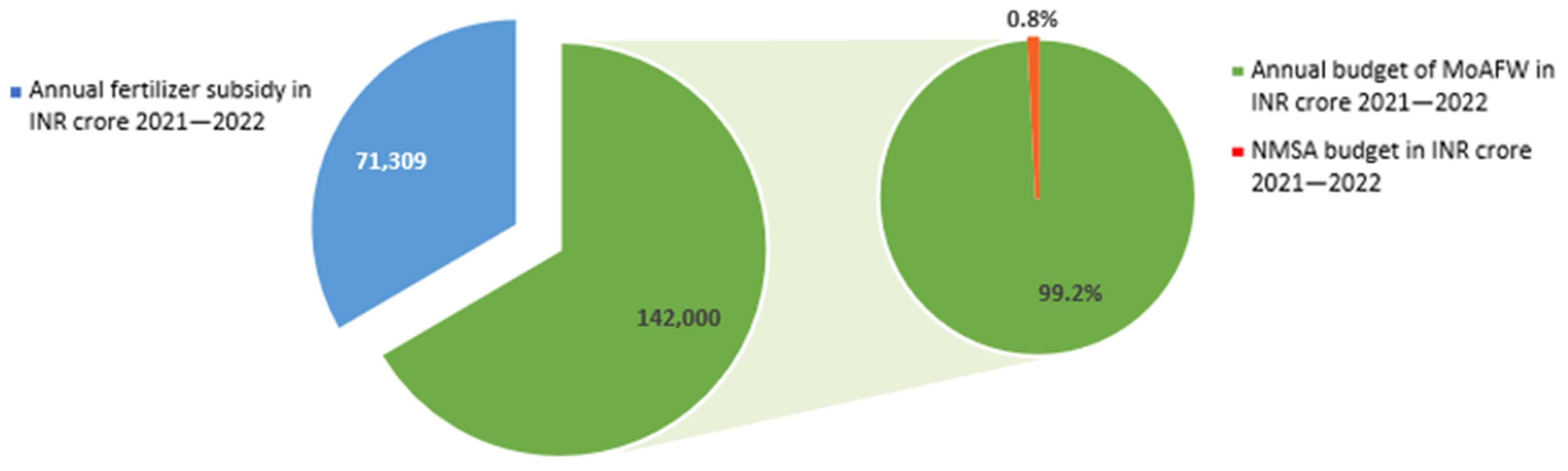

Nonetheless, the budget allocation to the NMSA is minuscule (0.8 percent) compared to the overall budget of the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare (MoAFW) (

Figure 4). Further, around INR 71,309 crore (USD 10 billion) is spent on fertiliser subsidies by the central government annually, in addition to MoAFW’s budget of INR 142,000 crore (USD 20 billion) [

9]. This showcases that although sustainable agriculture is being promoted, the support is heavily directed towards conventional farming or the green revolution-led cultivation approaches.

Only eight SAPSs receive some budgetary support: organic farming, vermicomposting, precision, contour farming, integrated farming, mulching, RWH, and IPM. Recently, the Bhartiya Prakritik Krishi Padhati was established to promote natural farming in 2020–21; however, the financial allocation of INR 12,200/ha (USD 162) [

10] for a three-year transition period is inadequate. A meagre INR 12 crore (USD 1.6 million) was dedicated to National Project on Organic Farming and only INR 34 crore (USD 4.7 million) to the National Project on Agroforestry for 2021–22 [

11]. Of all the practices, organic farming garners the most attention, as observed through several state organic farming policies.

4. Conclusions

India needs alternative approaches to farming, and our observations find sustainable practices to show potential for an easier transition in 60 percent of the drought-prone rainfed areas where agriculture endures in resource-constrained environments. It will diversify income opportunities for the 86 percent of the smallholder farmers for whom these practices are easier to embrace. Despite this, the adoption of sustainable agriculture remains low, although a few states like Andhra Pradesh and Sikkim managed to attain scale. The limited evidence on various indicators necessitates building long-term conclusive outcomes for SAPSs.

The budgetary allocation needs a significant upgrade, and certain SAPSs could be targeted and contextualised as per the region’s feasibility and agroclimatic characteristics. Farmers need to be supported to ease their situation in the transition phases and hand-holding required to build knowledge and capacity. Investing in these practices will further help tackle the core issues of malnutrition as the focus shifts towards nutrition security from food security. A long-term vision of sustainability for the agriculture sector will require a reorientation of our food, agriculture, and farm production systems supported by policy incentives that enable their scale-up efficiently and inclusively.