Knowledge and Attitudes of Croatian Nurses Toward Hypoglycemia Management: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Objectives

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Ethics

2.4. Participants

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Multivariable Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Ideas for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD Results; University of Washington: Seattle, WI, USA, 2024; Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Ruan, Y.; Moysova, Z.; Tan, G.D.; Lumb, A.; Davies, J.; Rea, R.D. Inpatient hypoglycaemia: Understanding who is at risk. Diabetologia 2020, 63, 1299–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, P. Inpatient Hypoglycemia: The Challenge Remains. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2020, 14, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beliard, R.; Muzykovsky, K.; Vincent, W., 3rd; Shah, B.; Davanos, E. Perceptions, Barriers, and Knowledge of Inpatient Glycemic Control: A Survey of Health Care Workers. J. Pharm. Pract. 2016, 29, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, A.; Al-Ganmi, A.; Gholizadeh, L.; Perry, L. Diabetes knowledge of nurses in different countries: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 39, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Méndez, R.; Harvey, D.J.R.; Windle, R.; Adams, G.G. The practice of glycaemic control in intensive care units: A multicent re survey of nursing and medical professionals. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 2088–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, B.M.; Arroll, B.; Scragg, R.K.R. Diabetes knowledge of primary health care and specialist nurses in a m ajor urban area. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 28, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikitara, M.; Constantinou, C.S.; Andreou, E.; Diomidous, M. The Role of Nurses and the Facilitators and Barriers in Diabetes Care: A Mixed Methods Systematic Literature Review. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-bawi, A.I.; Al-Hamdani, M.H.A.; Jouzi, M. Investigating the knowledge and attitude of nurses regarding hypoglycemia of diabetic patients hospitalized in Marjan Teaching Hospital in 2022. Kufa J. Nurs. Sci. 2024, 14, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, A.; Gholizadeh, L.; Al-Ganmi, A.; Perry, L. Examining perceived and actual diabetes knowledge among nurses working in a tertiary hospital. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2017, 35, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacoub, M.I.; Demeh, W.M.; Darawad, M.W.; Barr, J.L.; Saleh, A.M.; Saleh, M.Y. An assessment of diabetes-related knowledge among registered nurses working in hospitals in Jordan. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2014, 61, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndebu, J.; Jones, C. Inpatient nursing staff knowledge on hypoglycaemia management. J. Diabetes Nurs. 2018, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Isnani, S.-L.J.; Macalalad-Josue, A.; Jimeno, C.A. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Health Care Providers in the Philippine General Hospital towards In-Patient Hypoglycemia and its Management. Acta Medica Philipp. 2021, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byne, P. Hypoglycemia Treatment by Nurses: A Quality Improvement Strategy. Can. J. Diabetes 2018, 42, S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, K.E.; Gerard, S.O.; Krinsley, J.S. Reducing Hypoglycemia in Critical Care Patients Using a Nurse-Driven Root Cause Analysis Process. Crit. Care Nurse 2019, 39, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albagawi, B.; Alkubati, S.A.; Abdul-Ghani, R. Levels and predictors of nurses’ knowledge about diabetes care and management: Disparity between perceived and actual knowledge. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azami, G.; Soh, K.L.; Sazlina, S.G.; Salmiah, M.S.; Aazami, S.; Mozafari, M.; Taghinejad, H. Effect of a Nurse-Led Diabetes Self-Management Education Program on Gl ycosylated Hemoglobin among Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Diabetes Res. 2018, 2018, 4930157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.-K.; Kim, M.Y. Self-Management Nursing Intervention for Controlling Glucose among Dia betes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Liu, J.; Zeng, H.; He, G.; Ren, X.; Guo, J. Feasibility and efficacy of nurse-led team management intervention for improving the self-management of type 2 diabetes patients in a Chinese community: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2019, 13, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, F.; Wang, J.; Tao, Y. Effect of community-based nurse-led support intervention in the reduct ion of HbA1c levels. Public Health Nurs. 2022, 39, 1318–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, M.S.; Kieffer, E.C.; Sinco, B.; Piatt, G.; Palmisano, G.; Hawkins, J.; Lebron, A.; Espitia, N.; Tang, T.; Funnell, M.; et al. Outcomes at 18 Months from a Community Health Worker and Peer Leader D iabetes Self-Management Program for Latino Adults. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 1414–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, M.; Bektas, H.; Ozer, Z.C. The effect of nurse-led diabetes self-management programmes on glycosy lated haemoglobin levels in individuals with type 2 diabetes: A system atic review. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2023, 29, e13175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glenn, L.E.; Nichols, M.; Enriquez, M.; Jenkins, C. Impact of a community-based approach to patient engagement in rural, l ow-income adults with type 2 diabetes. Public Health Nurs. 2019, 37, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marelli, G.; Avanzini, F.; Iacuitti, G.; Planca, E.; Frigerio, I.; Busi, G.; Carlino, L.; Cortesi, L.; Roncaglioni, M.C.; Riva, E. Effectiveness of a nurse-managed protocol to prevent hypoglycemia in hospitalized patients with diabetes. J. Diabetes Res. 2015, 2015, 173956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, F.; Ahlborn, R.; Weidehoff, T. Nurse-Directed Blood Glucose Management in a Medical Intensive Care Un it. Crit. Care Nurse 2017, 37, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice, C. 16. Diabetes Care in the Hospital: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, S244–S253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, M.F.; Manchester, C.; Mathiason, M.A.; Wood, J.; Moore, A. Adherence to a Hypoglycemia Protocol in Hospitalized Patients. Nurs. Res. 2020, 70, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkendall, E.S. Casting a Wider Safety Net: The Promise of Electronic Safety Event Det ection Systems. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2017, 43, 153–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.A.Q.; Conover, C.; Shehab, N.; Geller, A.I.; Guerra, Y.S.; Kramer, H.; Kosacz, N.M.; Zhang, H.; Budnitz, D.S.; Trick, W.E. Electronic Measurement of a Clinical Quality Measure for Inpatient Hyp oglycemic Events. Med. Care 2020, 58, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, L.; Freeman, S.; Amarasekara, S.; Maza, A.; Setji, T. Evaluation of the Efficacy of a Hypoglycemia Protocol to Treat Severe Hypoglycemia. Clin. Nurse Spec. 2022, 36, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppy, A.; Retamal-Munoz, C.; Cree-Green, M.; Wood, C.; Davis, S.; Clements, S.A.; Majidi, S.; Steck, A.K.; Alonso, G.T.; Chambers, C.; et al. Reduction of Insulin Related Preventable Severe Hypoglycemic Events in Hospitalized Children. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20151404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.; Roseleur, J.; Edney, L.; Karnon, J. Southern Adelaide Local Health Network’s Hypoglycaemia Clinical Working, G. Pragmatic review of interventions to prevent inpatient hypoglycaemia. Diabet. Med. 2022, 39, e14737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Measure | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 61 | 19.24 |

| Female | 256 | 80.76 | |

| Age (years) | 19–25 | 65 | 20.50 |

| 26–35 | 90 | 28.39 | |

| 36–45 | 81 | 25.55 | |

| 46–55 | 44 | 13.88 | |

| >56 | 37 | 11.67 | |

| Education | High school | 100 | 31.54 |

| Higher vocational | 145 | 45.74 | |

| University level | 72 | 22.71 | |

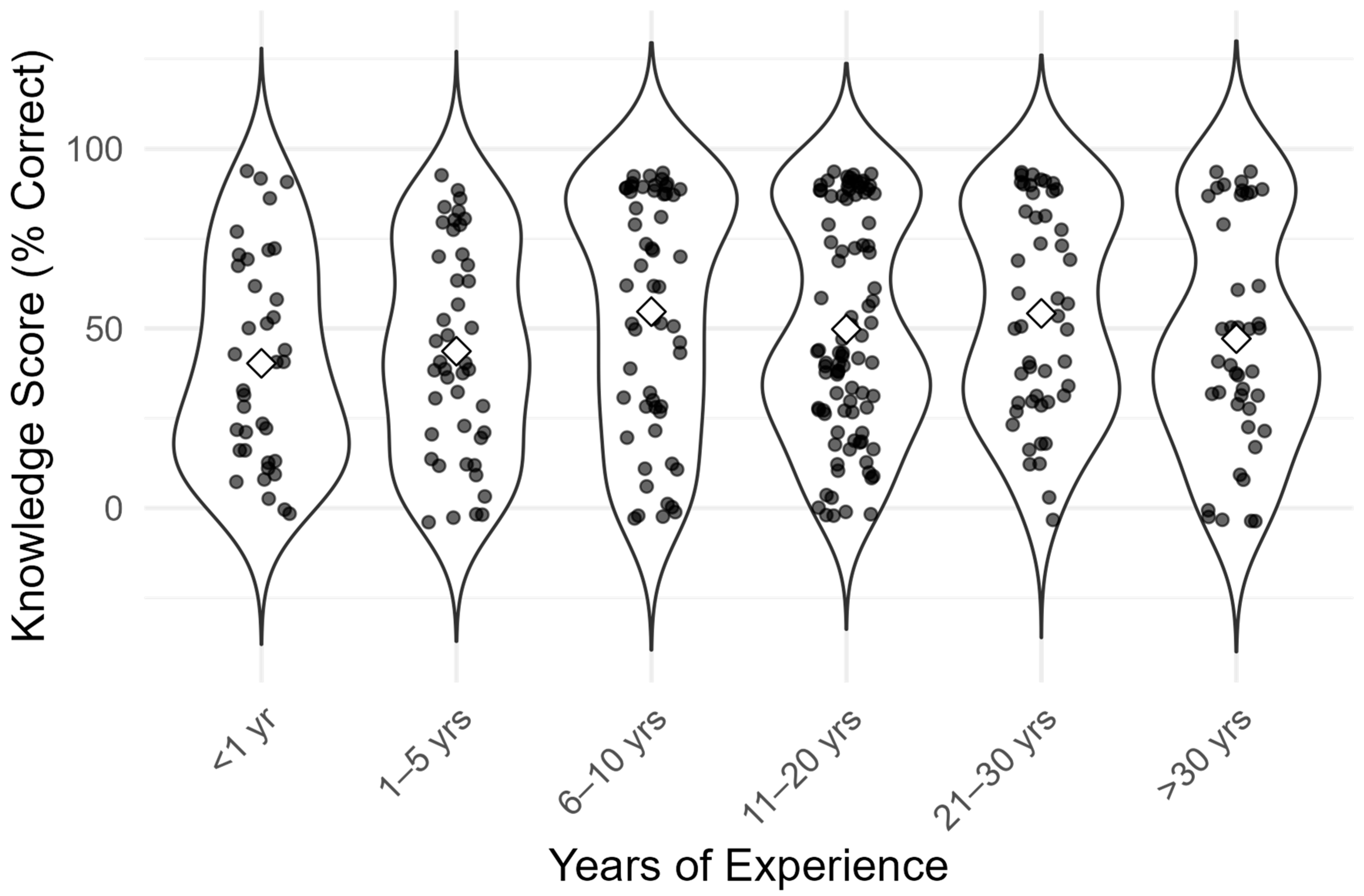

| Years of working | Less than 1 year | 37 | 11.67 |

| 1–5 years | 44 | 13.88 | |

| 6–10 years | 56 | 17.66 | |

| 11–20 years | 90 | 28.39 | |

| 21–30 years | 48 | 15.14 | |

| More than 30 years | 42 | 13.25 |

| Measure | Mean | Median | SD | Min | Max | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge score (%) | 66.9 | 65.4 | 17.8 | 23.1 | 88.5 | 317 |

| Attitude score (1–5 scale) | 3.42 | 3.67 | 0.70 | 2.00 | 4.83 | 317 |

| Correct Answer | Wrong Answer | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| What is the cut-off value of capillary blood glucose (mmol/L) for hypoglycemia? | ||||

| <4 mmol/L | 173 | 54.58 | 144 | 45.42 |

| What are the risk factors for hypoglycemia? | ||||

| Recovery from an acute illness | 206 | 64.98 | 111 | 35.02 |

| Insulin or oral hypoglycemia therapy at an inappropriate time in relation to a meal | 271 | 85.49 | 46 | 14.51 |

| List the symptoms of hypoglycemia. | ||||

| Hunger | 223 | 70.35 | 94 | 29.65 |

| Trembling | 284 | 89.59 | 33 | 10.41 |

| Sweating | 290 | 91.48 | 27 | 8.52 |

| Annoyance | 275 | 86.75 | 42 | 13.25 |

| Headache | 208 | 65.62 | 109 | 34.38 |

| Convulsions | 154 | 48.58 | 163 | 51.42 |

| Which of the following diabetes medications can cause hypoglycemia? | ||||

| Gliclazide | 156 | 49.21 | 161 | 50.79 |

| Insulin | 276 | 87.07 | 41 | 12.93 |

| 15 g of fast-acting carbohydrates is equal to: | ||||

| 3 dextrose candy | 163 | 51.42 | 154 | 48.58 |

| Which of the following is a neuroglycopenia symptom of hypoglycemia? | ||||

| Speech difficulties | 220 | 69.40 | 97 | 30.60 |

| Which of the following nutritional problems is a risk factor for developing hypoglycemia? | ||||

| Changing the time of eating the main meal of the day | 209 | 65.93 | 108 | 34.07 |

| Long time of starvation | 265 | 83.60 | 52 | 16.40 |

| Inability to access the usual snack | 191 | 60.25 | 126 | 39.75 |

| Eating less carbohydrates than usual | 179 | 56.47 | 138 | 43.53 |

| What intervention should be performed during an episode of hypoglycemia in a patient who is conscious and oriented? | ||||

| Give 200 mL of any juice | 253 | 79.81 | 64 | 20.19 |

| What interventions during an episode of hypoglycemia should be carried out in a patient who is unconscious or has convulsions? | ||||

| Check the patency of the airway, breathing, and circulation | 285 | 89.91 | 32 | 10.09 |

| Administer 1 mg of glucagon intramuscularly/subcutaneously | 255 | 80.44 | 62 | 19.56 |

| When should blood glucose be rechecked after an episode of hypoglycemia? | ||||

| 15 min after therapy | 200 | 63.09 | 117 | 36.91 |

| Attitude Statement | Median | IQR |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with hypoglycemia receive insufficient care compared to hyperglycemia | 3.00 | 2.00–4.00 |

| Management should include a multidisciplinary approach | 4.00 | 3.00–5.00 |

| Prevention and proper treatment do not reduce hospital costs * | 2.00 | 2.00–4.00 |

| Strict glycemic control is associated with good outcomes | 4.00 | 3.00–5.00 |

| Standardized protocols are additional work for nurses * | 2.00 | 2.00–4.00 |

| Guidelines improve patient prognosis | 4.00 | 3.00–5.00 |

| Comparison | U Value | p-Value | Effect Size (r) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge~Education | 19,507.0 | <0.001 | 0.641 | Large effect |

| Attitude~Education | 19,614.0 | <0.001 | 0.649 | Large effect |

| Knowledge~Experience | 11,305.0 | 0.013 | 0.138 | Small effect |

| Attitude~Experience | 8441.5 | 0.700 | 0.023 | No significant effect |

| Predictor | Knowledge ≥ 50% (OR [95% CI]) | Attitude Score (β [95% CI]) |

|---|---|---|

| Tertiary education | 68.30 [19.92, 234.21] | +1.02 [0.90, 1.15] |

| >5 years experience | 0.97 [0.38, 2.45] | –0.04 [–0.16, 0.10] |

| Female sex | 2.59 [1.02, 6.62] | +0.13 [–0.02, 0.28] |

| Emergency workplace | 4.78 [0.44, 52.11] | +0.26 [–0.03, 0.56] |

| Other workplaces | NS | NS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Majić, K.; Car, M. Knowledge and Attitudes of Croatian Nurses Toward Hypoglycemia Management: A Cross-Sectional Study. Diabetology 2025, 6, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6070065

Majić K, Car M. Knowledge and Attitudes of Croatian Nurses Toward Hypoglycemia Management: A Cross-Sectional Study. Diabetology. 2025; 6(7):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6070065

Chicago/Turabian StyleMajić, Karla, and Mate Car. 2025. "Knowledge and Attitudes of Croatian Nurses Toward Hypoglycemia Management: A Cross-Sectional Study" Diabetology 6, no. 7: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6070065

APA StyleMajić, K., & Car, M. (2025). Knowledge and Attitudes of Croatian Nurses Toward Hypoglycemia Management: A Cross-Sectional Study. Diabetology, 6(7), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6070065