Medical Doctors, Nurses, and Therapeutic Health Practitioners Knowledge of Risk Factors and Prevention of Diabetic Foot Ulcer: A Cross-Sectional Survey in a South African Setting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Area

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Research Participants

2.4. Study Questionnaire

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

Prior Training and Provisioning of Health Education to Patients

4. Discussion

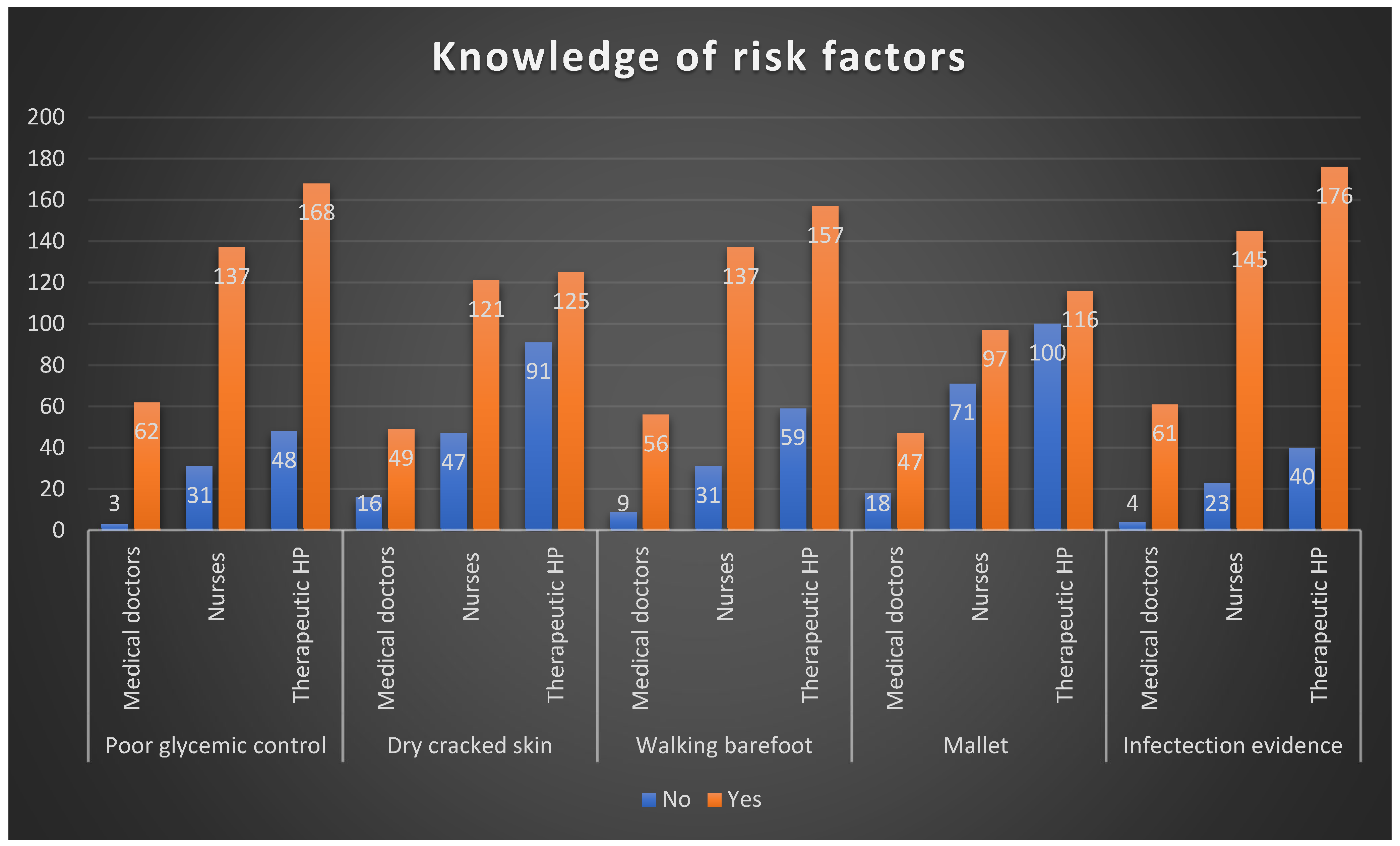

4.1. Healthcare Practitioners’ Knowledge of Risk Factors

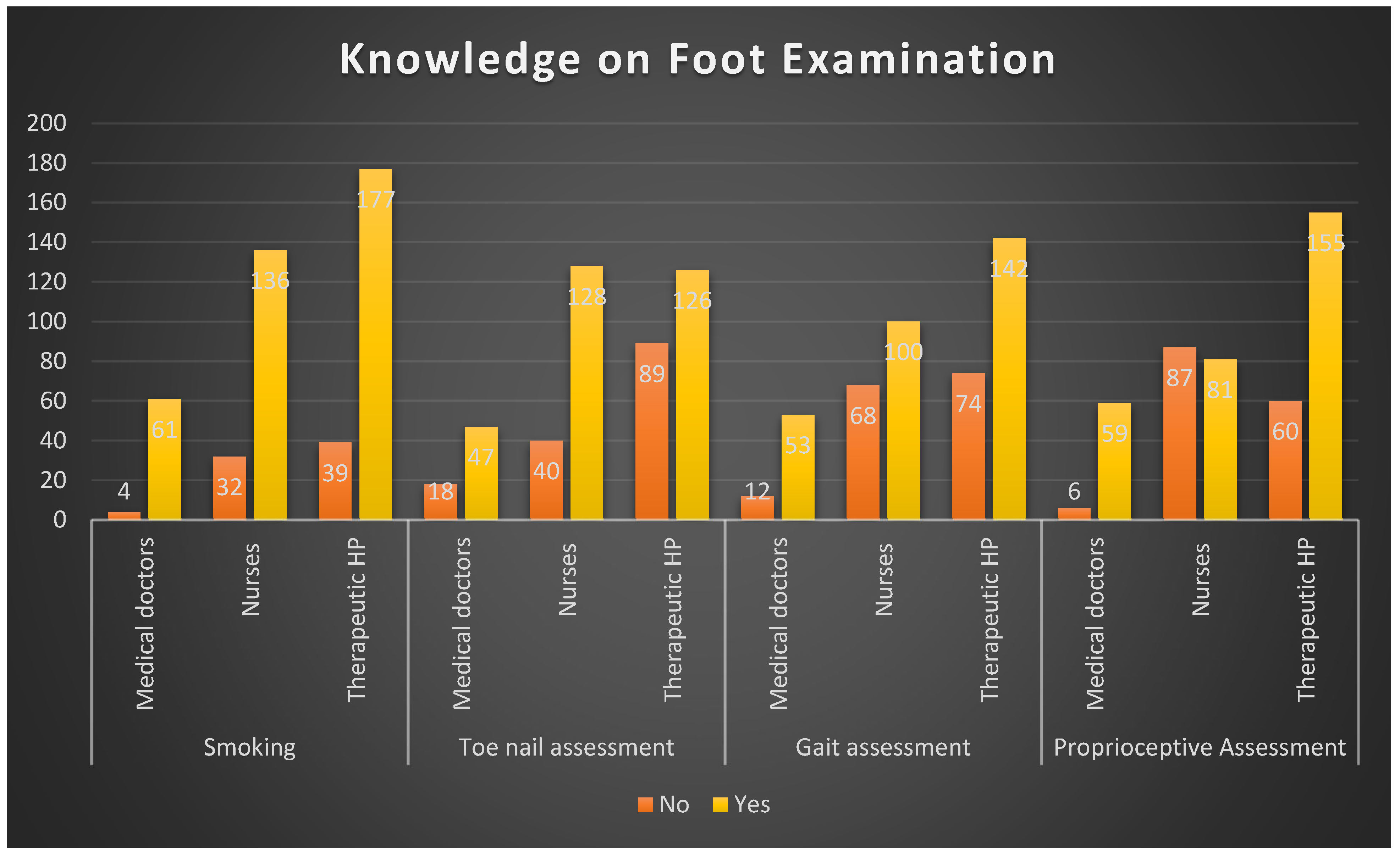

4.2. Knowledge of Proper Foot Examination Among Healthcare Professions

4.3. Knowledge Levels on Foot Care Among Professional Groups

4.4. Knowledge of Appropriate Selection and Use of Footwear

4.5. Knowledge of Limb-Threatening Conditions Among Healthcare Professionals

4.6. The Strength of the Study

4.7. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DFI | Diabetic foot infection |

| DFU | Diabetic foot ulcer |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| HCPs | Healthcare practitioners |

| THPs | Therapeutic health practitioners |

References

- Chaudhary, N.; Huda, F.; Roshan, R.; Basu, S.; Rajput, D.; Kumar Singh, S.K. Lower Limb Amputation Rates in Patients with Diabetes and an Infected Foot Ulcer: A Prospective Observational Study. Wound Manag. Prev. 2021, 67, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokoala, T.C.; Sididzha, V.; Molefe, E.D.; Luvhengo, T.E. Life Expectancy of Patients with Diabetic Foot Sepsis Post-Lower Extremity Amputation at a Regional Hospital in a South African Setting: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Surgeon 2024, 22, e109–e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Core, M.D.; Ahn, J.; Lewis, R.B.; Raspovic, K.M.; Lalli, T.A.J.; Wukich, D.K. The Evaluation and Treatment of Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Diabetic Foot Infections. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2018, 2018, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatem, M.A.; Kamal, D.M.; Yusuf, K.A. Diabetic Foot Limb-Threatening Infections: Case Series and Management Review. Int. J. Surg. Open 2022, 48, 100568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitocco, D.; Spanu, T.; Di Leo, M.; Vitiello, R.; Rizzi, A.; Tartaglione, L.; Fiori, B.; Caputo, S.; Tinelli, G.; Zaccardi, F.; et al. Diabetic Foot Infections: A Comprehensive Overview. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23 (Suppl. S2), 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Lu, J.; Jing, Y.; Zhu, D.; Bi, Y. Global Epidemiology of Diabetic Foot Ulceration: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Med. 2017, 49, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rubeaan, K.; Al Derwish, M.; Ouizi, S.; Youssef, A.M.; Subhani, S.N.; Ibrahim, H.M.; Alamri, B.N. Diabetic Foot Complications and Their Risk Factors from a Large Retrospective Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundlingh, N.; Zewotir, T.T.; Roberts, D.J.; Manda, S. Assessment of Prevalence and Risk Factors of Diabetes and Pre-Diabetes in South Africa. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2022, 41, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Netten, J.J.; Raspovic, A.; Lavery, L.A.; Monteiro-Soares, M.; Rasmussen, A.; Sacco, I.C.N.; Bus, S.A. Prevention of Foot Ulcers in the At-Risk Patient with Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2020, 36 (Suppl. S1), e3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpowska, K.; Majchrzycka, M.; Adamski, Z. The Assessment of Prophylactic and Therapeutic Methods for Nail Infections in Patients with Diabetes. Adv. Dermatol. Allergol./Postȩpy Dermatol. Alergol. 2022, 39, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bus, S.A.; Lavery, L.A.; Monteiro-Soares, M.; Rasmussen, A.; Raspovic, A.; Sacco, I.C.N.; van Netten, J.J. Guidelines on the Prevention of Foot Ulcers in Persons with Diabetes (IWGDF 2019 Update). Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2020, 36, e3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iraj, B.; Khorvash, F.; Ebneshahidi, A.; Askari, G. Prevention of Diabetic Foot Ulcer. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 4, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.Z.M.; Ng, N.S.L.; Thomas, C. Prevention and Treatment of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. J. R. Soc. Med. 2017, 110, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, C.; Da Ros, R.; Marfella, R. Update on Prevention of Diabetic Foot Ulcer. Arch. Med. Sci. Atheroscler. Dis. 2021, 6, e123–e131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullan, L.; Wynter, K.; Driscoll, A.; Rasmussen, B. Preventative and Early Intervention Diabetes-Related Foot Care Practices in Primary Care. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2020, 26, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsky, B.A.; Berendt, A.R.; Deery, H.G.; Embil, J.M.; Joseph, W.S.; Karchmer, A.W.; LeFrock, J.L.; Lew, D.P.; Mader, J.T.; Norden, C.; et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Diabetic Foot Infections. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006, 117, 212S–238S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorlaakso, M.; Kiiski, J.; Salonen, T.; Karppelin, M.; Helminen, M.; Kaartinen, I. Major Amputation Profoundly Increases Mortality in Patients with Diabetic Foot Infection. Front. Surg. 2021, 8, 655902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, A.J.; Armstrong, D.G.; Albert, S.F.; Frykberg, R.G.; Hellman, R.; Kirkman, M.S.; Lavery, L.A.; Lemaster, J.W.; Mills, J.L., Sr.; Mueller, M.J.; et al. Comprehensive Foot Examination and Risk Assessment: A Report of the Task Force of the Foot Care Interest Group of the American Diabetes Association, with Endorsement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 1679–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, J.; Sibbald, R.G.; Taha, N.Y.; Lebovic, G.; Rambaran, M.; Martin, C.; Bhoj, I.; Ostrow, B. The Guyana Diabetes and Foot Care Project: Improved Diabetic Foot Evaluation Reduces Amputation Rates by Two-Thirds in a Lower Middle Income Country. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 2015, 920124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Netten, J.J.; Lazzarini, P.A.; Armstrong, D.G.; Bus, S.A.; Fitridge, R.; Harding, K.; Kinnear, E.; Malone, M.; Menz, H.B.; Perrin, B.M.; et al. Diabetic Foot Australia Guideline on Footwear for People with Diabetes. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2018, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, L.; Driscoll, A.; Wynter, K.; Rasmussen, B. Barriers and Enablers to Delivering Preventative and Early Intervention Footcare to People with Diabetes: A Scoping Review of Healthcare Professionals’ Perceptions. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2019, 25, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nancy, N.S.W.; Ruby, J.A.; Durai, S.; Naik, D. Awareness and Practices of Footwear Among Patients with Diabetes and a High-Risk Foot. Diabet. Foot J. 2020, 23, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Isip, J.D.Q.; de Guzman, M.; Ebison, A.; Narvacan-Montano, C. Footwear Appropriateness, Preferences, and Foot Ulcer Risk Among Adult Diabetics at Makati Medical Center Outpatient Department. J. ASEAN Fed. Endocr. Soc. 2016, 31, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buldt, A.K.; Menz, H.B. Incorrectly Fitted Footwear, Foot Pain and Foot Disorders: A Systematic Search and Narrative Review of the Literature. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2018, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundram, E.R.; Sidek, M.Y.; Yew, T.S. Types and Grades of Footwear and Factors Associated with Poor Footwear Choice Among Diabetic Patients in USM Hospital. Int. J. Public Health Clin. Sci. 2018, 5, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, A.; Naemi, R.; Chockalingam, N. The Effectiveness of Footwear as an Intervention to Prevent or to Reduce Biomechanical Risk Factors Associated with Diabetic Foot Ulceration: A systematic review. J. Diabetes Its Complicat. 2013, 27, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgetto, J.V.; Gamba, M.A.; Kusahara, D.M. Evaluation of the Use of Therapeutic Footwear in People with Diabetes Mellitus—A Scoping Review. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2019, 18, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilal, M.; Haseeb, A.; Rehman, A.; Hussham Arshad, M.; Aslam, A.; Godil, S.; Qamar, M.A.; Husain, S.N.; Polani, M.H.; Ayaz, A.; et al. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Among Nurses in Pakistan Towards Diabetic Foot. Cureus 2018, 10, e3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustamu, A.C.; Samaran, E.; Bistara, D.N. Impact of Poor Glycemic Control and Vascular Complications on Diabetic Foot Ulcer Recurrence. J. Angiother. 2024, 8, 9854. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, D.F.; Edelman, S.V.; Hinnen, D.A.; Parkin, C.G. Reference Guide for Integrating Continuous Glucose Monitoring into Clinical Practice. Diabetes Educ. 2018, 45, 3S–20S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesudian, P.D.; Nwabudike, L.C.; de Berker, D. Nail Changes in Diabetes. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanasundaram, S.; Ramalingam, P.; Das, B.N.; Viswanathan, V. Gait Changes in Persons with Diabetes: Early Risk Marker for Diabetic Foot Ulcer. Foot Ankle Surg. 2020, 26, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, L.; Wynter, K.; Driscoll, A.; Rasmussen, B. Prioritisation of Diabetes-Related Footcare Amongst Primary Care Healthcare Professionals. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 4653–4673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranuve, M.S.; Mohammadnezhad, M. Healthcare workers’ perceptions on diabetic foot ulcers (DFU) and foot care in Fiji: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wui, N.B.; Azhar, A.A.; Azman, M.H.; Sukri, M.S.; Singh, A.S.; Abdul Wahid, A.M. Knowledge and Attitude of Nurses Towards Diabetic Foot Care in a Secondary Health Care Centre in Malaysia. Med. J. Malays. 2020, 75, 391–395. [Google Scholar]

- Alsaigh, S.H.; Alzaghran, R.H.; Alahmari, D.A.; Hameed, L.N.; Alfurayh, K.M.; Alaq, K.B. Knowledge, Awareness, and Practice Related to Diabetic Foot Ulcer Among Healthcare Workers and Diabetic Patients and Their Relatives in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2022, 14, e32221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noureen, R.; Warsi, M.; Nazir, A.; Mukhtar, M. Knowledge and Practice Related to Diabetic Foot Ulcers Among Healthcare Providers in a Public Hospital of Pakistan. Biol. Clin. Sci. Res. J. 2023, 4, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafusi, L.G.; Egenasi, C.K.; Steinberg, W.J.; Benedict, M.O.; Habib, T.; Harmse, M.J.; Van Rooyen, C. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices on Diabetic Foot Care Among Nurses in Kimberley, South Africa. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2024, 66, a5935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolt, M.; Suhonen, R.; Puukka, P.; Viitanen, P.; Voutilainen, P.; Leino-Kilpi, H. Nurses’ Knowledge of Foot Care in the Context of Home Care: A Cross-Sectional Correlational Survey Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 2916–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, M.; Bouillet, B.; Ahluwalia, R.; Sanchez-Rios, J.D.; Iacopi, E.; Izzo, V.; Manu, C.; Julien, V.; Luedmann, C.; Garcia-Klepzig, J.L.; et al. Validation of the Fast-Track Model: A Simple Tool to Assess the Severity of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsky, B.A.; Uçkay, I. Treating Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis: A Practical State-of-the-Art. Update. Medicina 2021, 57, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutluoglu, M.; Sivrioglu, A.K.; Eroglu, M.; Uzun, G.; Turhan, V.; Ay, H.; Lipsky, B.A. The implications of the presence of osteomyelitis on outcomes of infected diabetic foot wounds. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 45, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickinson, A.T.O.; Bridgwood, B.; Houghton, J.S.M.; Nduwayo, S.; Pepper, C.; Payne, T.; Bown, M.J.; Davies, R.S.M.; Sayers, R.D. A Systematic Review Investigating the Identification, Causes, and Outcomes of Delays in the Management of Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia and Diabetic Foot Ulceration. J. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 71, 669–681.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Number |

|---|---|

| Profession | |

| Medical doctors | 65 (14.5%) |

| Nurses | 168 (37.4%) |

| Therapeutic health practitioners | 216 (48.1%) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 120 (26.7%) |

| Female | 320 (71.3%) |

| Not specified | 9 (2%) |

| Service unit | |

| Polyclinic | 70 (15.6%) |

| Rehabilitation unit | 150 (33.4%) |

| Therapeutic unit | 56 (12.5%) |

| Medical-related unit | 90 (20%) |

| Surgical-related unit | 32 (7.1%) |

| Not specified | 51 (11.4%) |

| Variable | Total | Medical Doctors | Nurses | Therapeutic Health Practitioners | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior training in diabetic foot care | |||||

| No | 284 (63.3%) | 37 (57%) | 96 (59%) | 151 (71%) | 0.032 |

| Yes | 157 (35%) | 26 (40%) | 68 (41%) | 63 (29%) | |

| Not specified | 8 (1.8%) | 2 (0.4%) | 8 (4.8%) | 2 (0.9%) | |

| Training platform and nature | |||||

| Undergraduate | 78 (17.3%) | 30 (46.2%) | 24 (114.3%) | 24 (11.1%) | |

| Short course | 36 (5.8%) | 5 (7.7%) | 18 (10.7%) | 13 (6%) | |

| Workshops, in-service training, seminars, symposium or CPD activities | 17 (3.8%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (2.4%) | 11 (5.1%) | |

| On-site training or self-training | 19 (4.2%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (5.4%) | 10 (4.6%) | |

| Education of patients on foot care | |||||

| No | 153 (35%) | 13 (20%) | 54 (34%) | 86 (41%) | 0.008 |

| Yes | 284 (65%) | 52 (80%) | 107 (66%) | 125 (59%) | |

| Footwear Variables | Total | Medical Doctors | Nurses | Therapeutic Health Practitioners | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoes should fit and grasp feet | 0.782 | ||||

| Disagree | 215 (48%) | 33 (51%) | 82 (49%) | 100 (46%) | |

| Agree | 234 (52%) | 32 (49%) | 86 (51%) | 116 (54%) | |

| High-heeled shoes should be preferred | 0.117 | ||||

| Disagree | 38 (8%) | 5 (8%) | 20 (12%) | 13 (6%) | |

| Agree | 411 (92%) | 60 (92%) | 148 (88%) | 203 (94%) | |

| New shoes should be worn and allow feet to adjust to them | 0.357 | ||||

| Disagree | 194 (43%) | 29 (45%) | 79 (47%) | 86 (40%) | |

| Agree | 255 (57%) | 36 (55%) | 89 (53%) | 130 (60%) | |

| Shoes should be painted frequently | 0.915 | ||||

| Disagree | 62 (14%) | 8 (12%) | 23 (14%) | 31 (14%) | |

| Agree | 387 (86%) | 57 (88%) | 145 (86%) | 185 (86%) | |

| If there is a deformity in the foot, a doctor should be consulted for proper treatment or orthopaedic shoes | 0.303 | ||||

| Disagree | 89 (20%) | 14 (22%) | 27 (16%) | 48 (22%) | |

| Agree | 360 (80%) | 51 (78%) | 141 (84%) | 168 (78%) | |

| A shoe should not lose its exterior protection feature | 0.894 | ||||

| Disagree | 142 (32%) | 21 (32%) | 55 (33%) | 66 (31%) | |

| Agree | 307 (68%) | 44 (68%) | 113 (67%) | 150 (69%) | |

| Shoes should be worn without socks and, if shoe insoles are worn out, they should be replaced | 0.057 | ||||

| Disagree | 365 (81%) | 55 (85%) | 127 (76%) | 183 (85%) | |

| Agree | 84 (19%) | 10 (15%) | 41 (24%) | 22 (15%) | |

| Soft-skinned and comfortable shoes should be preferred | 0.944 | ||||

| Disagree | 71 (16%) | 11 (17%) | 27 (16%) | 33 (15%) | |

| Agree | 378 (86%) | 54 (83%) | 141 (86%) | 183 (85%) | |

| Shoes should be checked for foreign bodies such as nail, gravel, etc. before each wear | 0.334 | ||||

| Disagree | 59 (13%) | 5 (8%) | 25 (15%) | 29 (13%) | |

| Agree | 389 (87%) | 60 (92%) | 142 (85%) | 187 (87%) |

| Variables for Limb Threatening Conditions | Total | Medical Doctor | Nurses | Therapeutic Health Practitioners | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic limb ischemia | 0.335 | ||||

| Disagree | 93 (21%) | 9 (14%) | 37 (22%) | 47 (22%) | |

| Agree | 357 (79%) | 56 (86%) | 131 (78%) | 169 (78%) | |

| Osteomyelitis | <0.0001 | ||||

| Disagree | 166 (37%) | 8 (12%) | 58 (35%) | 100 (46%) | |

| Agree | 283 (63%) | 57 (88%) | 110 (65%) | 116 (54%) | |

| Extensive soft tissue loss | 0.023 | ||||

| Disagree | 107 (24%) | 7 (11%) | 41 (24%) | 59 (27%) | |

| Agree | 342 (76%) | 58 (89%) | 127 (76%) | 157 (73%) | |

| Rapid progression of infection | 0.992 | ||||

| Disagree | 156 (35%) | 23 (35%) | 58 (35%) | 75 (35%) | |

| Agree | 293 (65%) | 42 (65%) | 110 (65%) | 141 (65%) | |

| Extensive bony destruction of the foot | 0.574 | ||||

| Disagree | 128 (29%) | 15 (23%) | 49 (29%) | 64 (30%) | |

| Agree | 321 (71%) | 50 (77%) | 119 (71%) | 152 (70%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mukheli, T.; Fourie, A.; Mokoena, T.P.; Kagodora, S.B.; Luvhengo, T.E. Medical Doctors, Nurses, and Therapeutic Health Practitioners Knowledge of Risk Factors and Prevention of Diabetic Foot Ulcer: A Cross-Sectional Survey in a South African Setting. Diabetology 2025, 6, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6040031

Mukheli T, Fourie A, Mokoena TP, Kagodora SB, Luvhengo TE. Medical Doctors, Nurses, and Therapeutic Health Practitioners Knowledge of Risk Factors and Prevention of Diabetic Foot Ulcer: A Cross-Sectional Survey in a South African Setting. Diabetology. 2025; 6(4):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6040031

Chicago/Turabian StyleMukheli, Tshifhiwa, Anschen Fourie, Tshepo P. Mokoena, Shingirai B. Kagodora, and Thifhelimbilu E. Luvhengo. 2025. "Medical Doctors, Nurses, and Therapeutic Health Practitioners Knowledge of Risk Factors and Prevention of Diabetic Foot Ulcer: A Cross-Sectional Survey in a South African Setting" Diabetology 6, no. 4: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6040031

APA StyleMukheli, T., Fourie, A., Mokoena, T. P., Kagodora, S. B., & Luvhengo, T. E. (2025). Medical Doctors, Nurses, and Therapeutic Health Practitioners Knowledge of Risk Factors and Prevention of Diabetic Foot Ulcer: A Cross-Sectional Survey in a South African Setting. Diabetology, 6(4), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6040031