Exploring the Relationship Between Health Biomarkers and Performance on a Novel Color Perimetry Device in Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes

Abstract

1. Introduction

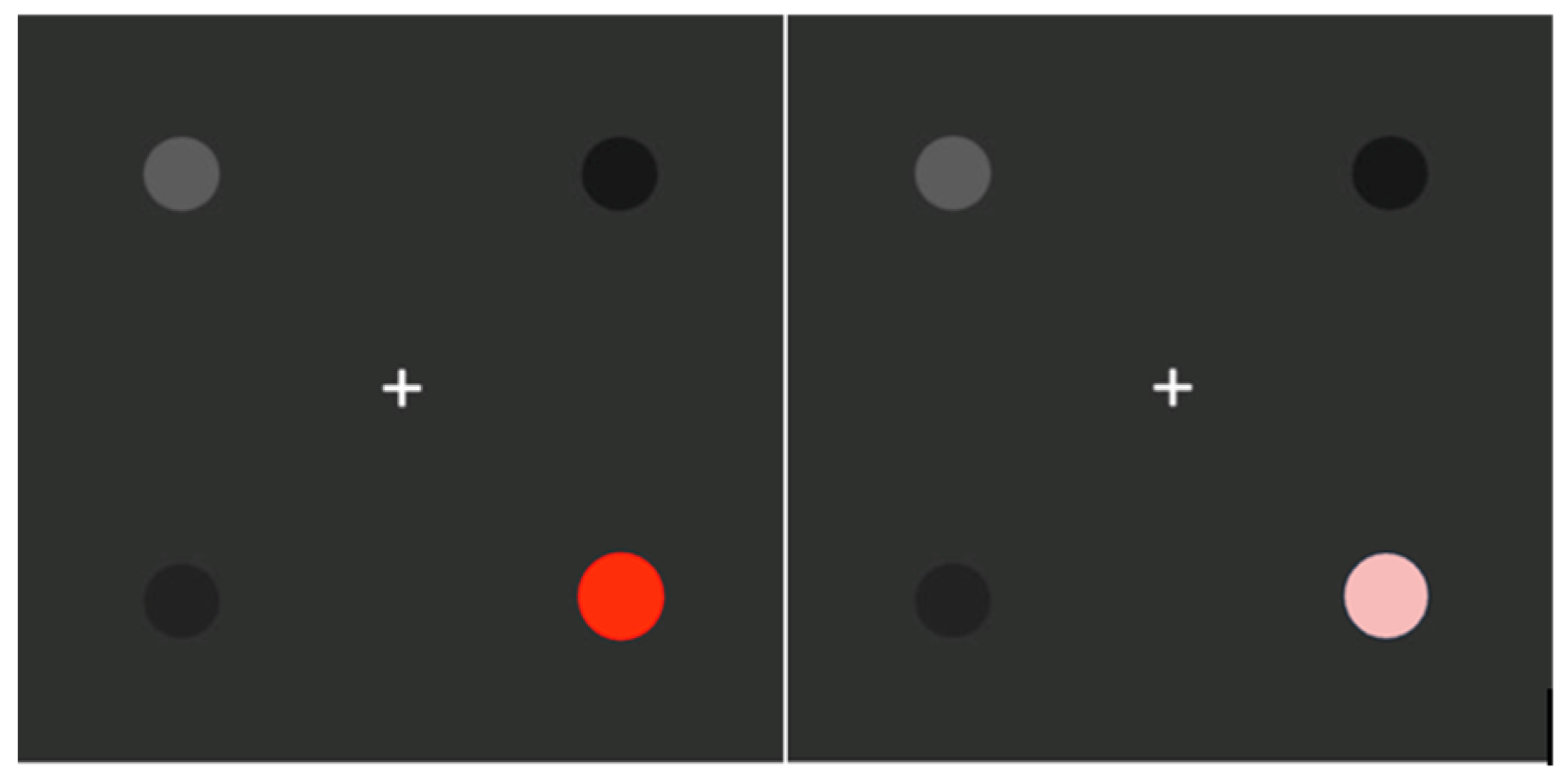

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Systemic Health Biomarkers

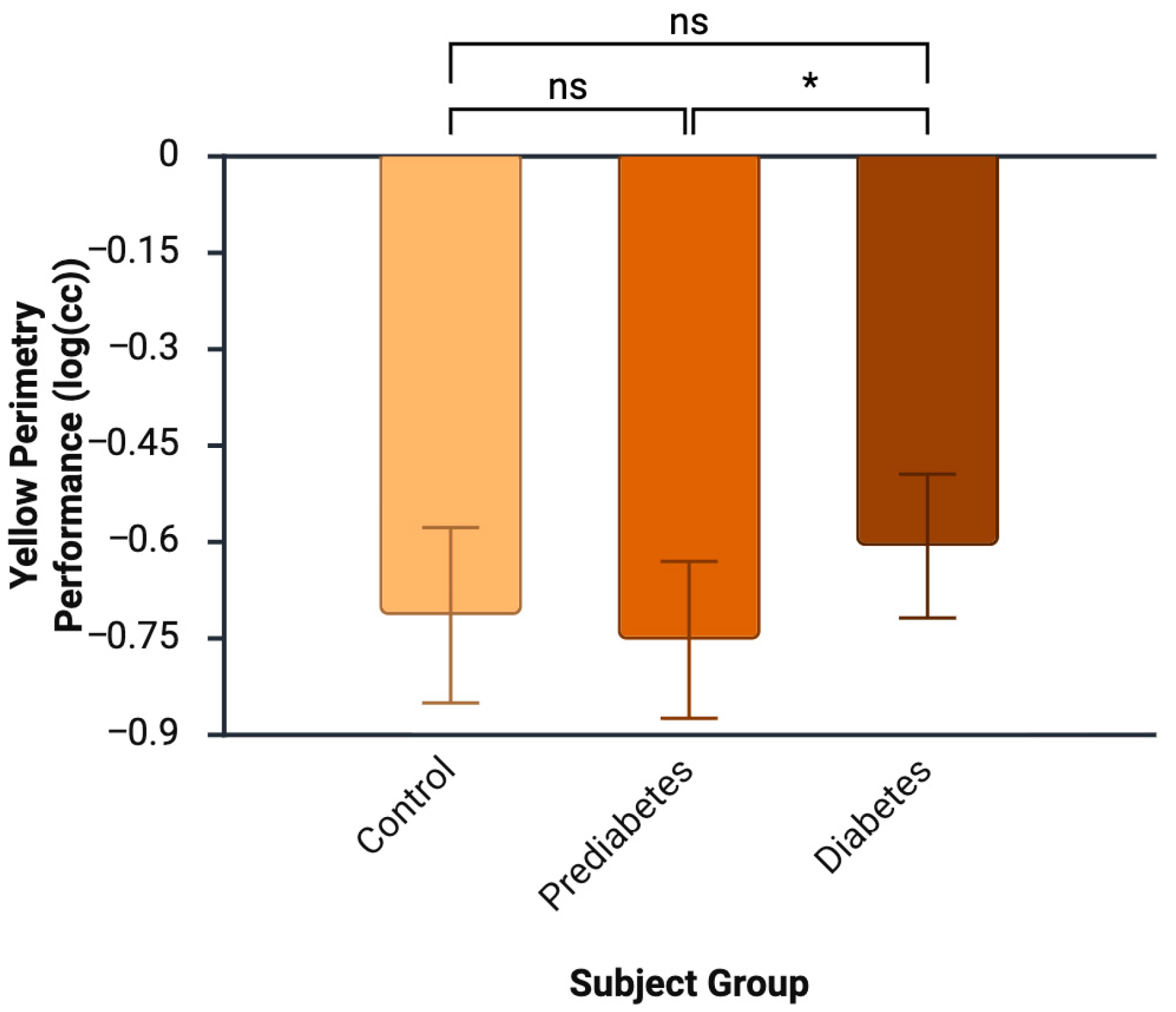

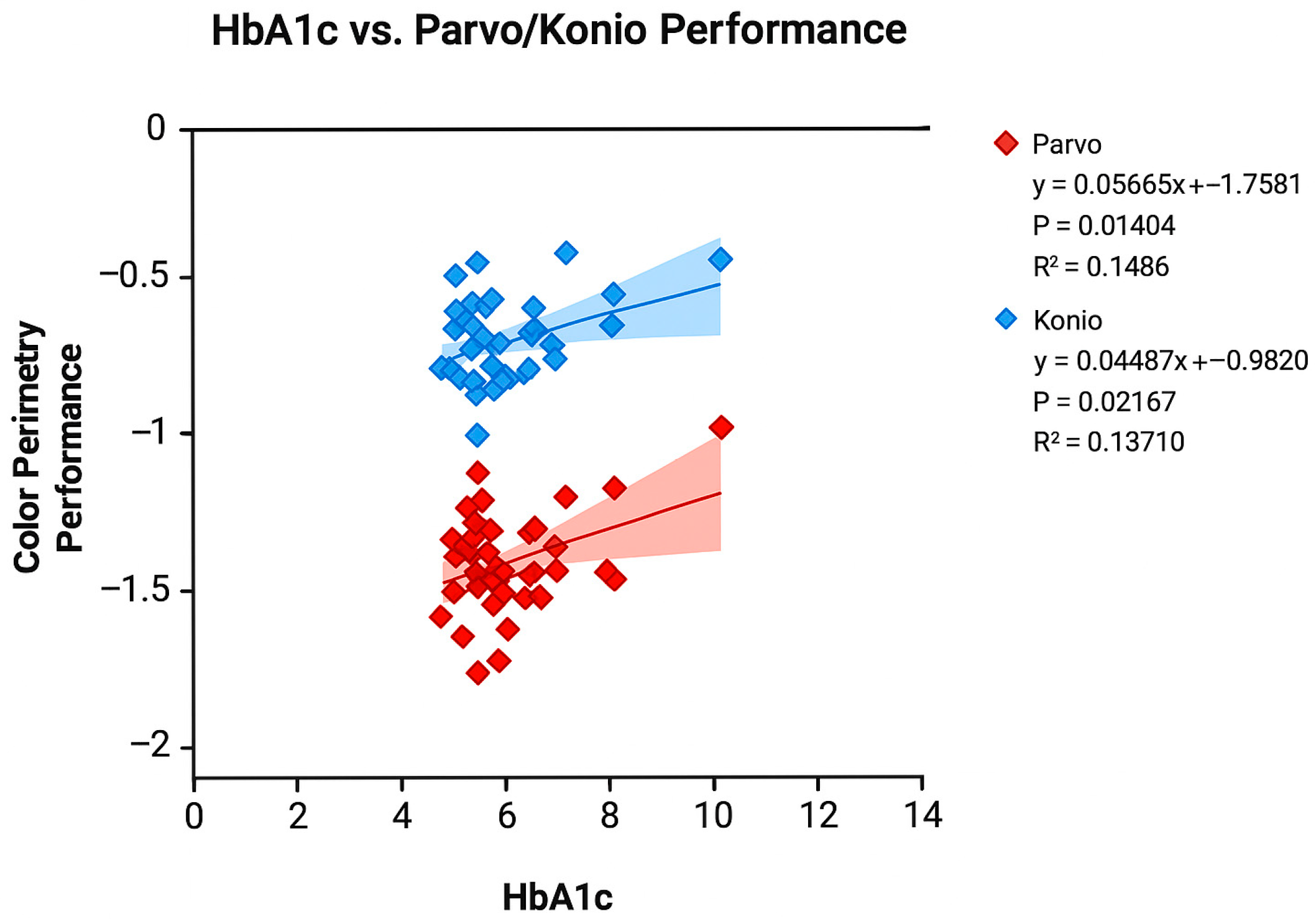

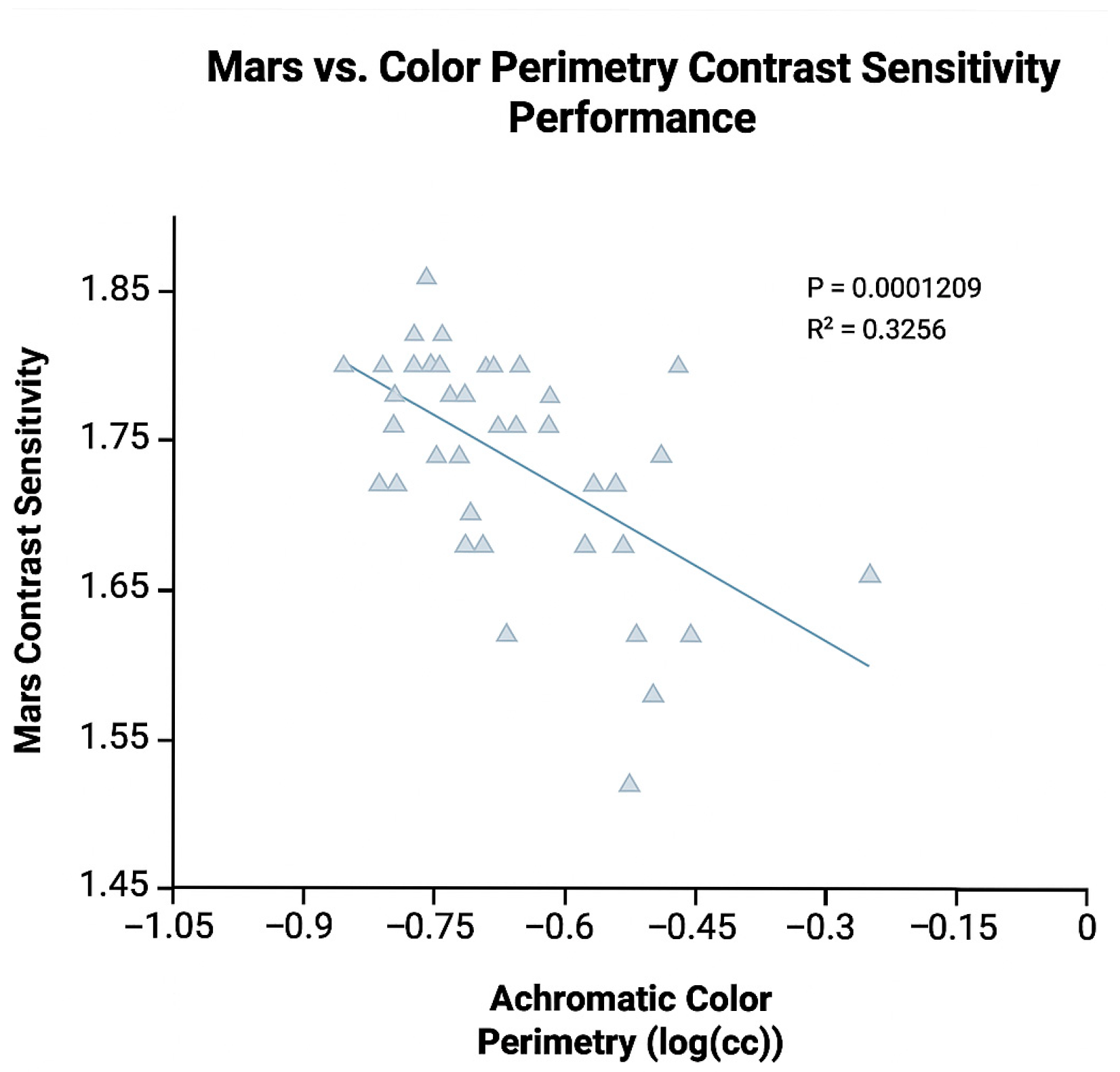

3.2. Color Perimetry and Other Ocular Tests

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes |

| HbA1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| HDL | High-Density Lipoprotein |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| DR | Diabetic Retinopathy |

| DM | Diabetes |

| PreDM | Prediabetes |

| LOCS | Lens Opacities Classification System |

| ETDRS | Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study |

| CS | Contrast Sensitivity |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

References

- Klein, B.E. Overview of epidemiologic studies of diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007, 14, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.Y.; Cheung, C.M.; Larsen, M.; Sharma, S.; Simó, R. Diabetic retinopathy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2016, 2, 16012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Zhang, L.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Zhu, X. Association between abdominal obesity and diabetic retinopathy in patients with diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0279734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simó, R.; Simó-Servat, O.; Bogdanov, P.; Hernández, C. Diabetic Retinopathy: Role of Neurodegeneration and Therapeutic Perspectives. Asia Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 11, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, C.; Dal Monte, M.; Simó, R.; Casini, G. Neuroprotection as a Therapeutic Target for Diabetic Retinopathy. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 2016, 9508541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanguilder, H.D.; Gardner, T.W.; Barber, A. Neuroglial Dysfunction in Diabetic Retinopathy. In Diabetic Retinopathy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gella, L.; Raman, R.; Kulothungan, V.; Pal, S.S.; Ganesan, S.; Sharma, T. Impairment of Colour Vision in Diabetes with No Retinopathy: Sankara Nethralaya Diabetic Retinopathy Epidemiology and Molecular Genetics Study (SNDREAMS-II, Report 3). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gella, L.; Raman, R.; Kulothungan, V.; Pal, S.S.; Ganesan, S.; Srinivasan, S.; Sharma, T. Color vision abnormalities in type II diabetes: Sankara Nethralaya Diabetic Retinopathy Epidemiology and Molecular Genetics Study II report no 2. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 65, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feitosa-Santana, C.; Paramei, G.V.; Nishi, M.; Gualtieri, M.; Costa, M.F.; Ventura, D.F. Color vision impairment in type 2 diabetes assessed by the D-15d test and the Cambridge Colour Test. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2010, 30, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gella, L.; Raman, R.; Pal, S.S.; Ganesan, S.; Sharma, T. Contrast sensitivity and its determinants in people with diabetes: SN-DREAMS-II, Report No 6. Eye 2017, 31, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, G.M.; Whitaker, D. Early detection of changes in visual function in diabetes mellitus. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 1998, 18, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, R.V.; Farrell, U.; Banford, D.; Jones, C.; Gregory, J.W.; Butler, G.; Owens, D.R. Visual function in young IDDM patients over 8 years of age. A 4-year longitudinal study. Diabetes Care 1997, 20, 1724–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, F.M.; Deary, I.J.; Strachan, M.W.; Frier, B.M. Seeing beyond retinopathy in diabetes: Electrophysiological and psychophysical abnormalities and alterations in vision. Endocr. Rev. 1998, 19, 462–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, M.; Xia, L.; Dong, J.; Xu, G.; Wang, Z.; Feng, L.; Zhou, Y. New Evidence of Central Nervous System Damage in Diabetes: Impairment of Fine Visual Discrimination. Diabetes 2022, 71, 1772–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, M.; Tay, N.; Kalitzeos, A.; Kane, T.; Singh, N.; Zheng, A.; Dixit, M.; Pal, B.; Rajendram, R.; Balaskas, K.; et al. Changes in Waveguiding Cone Photoreceptors and Color Vision in Patients With Diabetes Mellitus. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2024, 65, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, L.T.; Chen, C.C.; Hou, C.H.; Liao, K.M. Achromatic and chromatic contrast discrimination in patients with type 2 diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, V.T.S.; Symons, R.C.A.; Fourlanos, S.; Guest, D.; McKendrick, A.M. Contrast Increment and Decrement Processing in Individuals With and Without Diabetes. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pramanik, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Ganguly, U.; Banerjee, A.; Bhattacharya, B.; Mondal, L.K. Visual contrast sensitivity could be an early marker of diabetic retinopathy. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, H.; Nelson, R.F.; Ahnelt, P.K.; Ortuno-Lizaran, I.; Cuenca, N. The Architecture of the Human Fovea; University of Utah Health Sciences Center: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 1995; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Owusu-Afriyie, B.; Wu, C.S.; Burhans, L.; Coates, D.R.; Harrison, W.W. Repeatability of a novel chromatic perimeter in a cohort of people with and without glucose dysfunction. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2025, 102, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, G.R.; Hine, T. Computation of cone contrasts for color vision research. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 1992, 24, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, M.; Li, X.; Qiu, W.; Hou, Z.; Su, J.; Wang, W. The impact of age-related cataracts on colour perception, postoperative recovery and related spectra derived from test of hue perception. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019, 19, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenstein, V.C.; Shapiro, A.; Hood, D.C.; Zaidi, Q. Chromatic and luminance sensitivity in diabetes and glaucoma. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A Opt. Image Sci. Vis. 1993, 10, 1785–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, K.J.; Lipton, J.; Scase, M.O.; Foster, D.H.; Scarpello, J.H. Detection of colour vision abnormalities in uncomplicated type 1 diabetic patients with angiographically normal retinas. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1992, 76, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.S.; Owusu-Afriyie, B.; Benoit, J.; Harrison, W.W.; Coates, D.R. Consistency in the hill of vision regardless of chromaticity and diabetes status. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2025, 66, 532. [Google Scholar]

- Nanji, K.; Grad, J.; Hatamnejad, A.; El-Sayes, A.; Mihalache, A.; Gemae, M.; Huang, R.; Philips, M.; Kaiser, P.K.; Munk, M.R.; et al. Baseline OCT Biomarkers Associated with Visual Acuity in Diabetic Macular Edema: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2025, 25, S0161-6420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chondrozoumakis, G.; Chatzimichail, E.; Habra, O.; Vounotrypidis, E.; Papanas, N.; Gatzioufas, Z.; Panos, G.D. Retinal Biomarkers in Diabetic Retinopathy: From Early Detection to Personalized Treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, Z.; Dadzie, A.K.; Abtahi, M.; Ebrahimi, B.; Adejumo, T.; Taeyoon, S.; Lim, J.I.; Yao, X. Quantitative optical coherence tomography angiography biomarkers of the choriocapillaris for objective detection of early diabetic retinopathy. Taiwan J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 15, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Gaur, S.; Agarwal, R.; Singh, N.; Singh, A.; Parveen, S.; Singh, N.; Rima, N. Disorganization of retinal inner layers as an optical coherence tomography biomarker in diabetic retinopathy: A review. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 73, 1245–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Medrano, J.; Udaondo Mirete, P.; Fernández-Jiménez, M.; Asencio-Duran, M.; Ignacio Fernández-Vigo, J.; Medina-Baena, M.; Flores-Moreno, I.; Pareja-Esteban, J.; Touhami, S.; Giocanti-Aurégan, A.; et al. Biomarkers of risk of switching to dexamethasone implant for the treatment of diabetic macular oedema in real clinical practice: A multicentric study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 109, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Guo, Y.; Hormel, T.T.; Wang, J.; White, E.; Park, D.; Hwang, T.S.; Bailey, S.T.; Jia, Y. Nonperfused Retinal Capillaries-A New Method Developed on OCT and OCTA. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2025, 66, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | N | Age (yrs) | HbA1c (%) | Glucose (mg/dL) | BMI (kg/m2) | Body Fat (%) | Systolic BP (mmHg) | Diastolic BP (mmHg) | Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | HDL (mg/dL) | LDL (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 15 | 46.47 ± 7.81 | 5.28 ± 0.22 | 92.07 ± 10.99 | 25.26 ± 4.66 | 24.96 ± 9.72 | 123.13 ± 12.80 | 86.67 ± 8.53 | 185.40 ± 45.91 | 51.00 ± 16.51 | 118.15 ± 33.25 |

| PreDM | 10 | 44.80 ± 9.99 | 5.93 ± 0.21 | 116.60 ± 28.64 | 26.05 ± 8.57 | 27.15 ± 15.05 | 129.10 ± 21.46 | 87.90 ± 11.55 | 192.20 ± 39.07 | 49.00 ± 13.41 | 122.88 ± 35.86 |

| T2DM | 15 | 50.13 ± 7.03 | 7.05 ± 1.15 | 125.67 ± 41.40 | 31.08 ± 6.71 | 36.55 ± 8.68 | 122.80 ± 15.02 | 84.93 ± 9.18 | 169.13 ± 38.92 | 43.27 ± 17.26 | 95.33 ± 40.48 |

| p = 0.245 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.012 | p = 0.047 | p = 0.019 | p = 0.584 | p = 0.741 | p = 0.360 | p = 0.410 | p = 0.189 | ||

| F = 1.460 | F = 22.48 | F = 4.987 | F = 3.340 | F = 4.391 | F = 0.545 | F = 0.303 | F = 1.050 | F = 0.914 | F = 1.764 |

| Group | N | Achromatic (logcc) | Red (logcc) | Green (logcc) | Blue (logcc) | Yellow (logcc) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 15 | −0.67 ± 0.11 | −1.48 ± 0.15 | −1.36 ± 0.19 | −0.73 ± 0.18 | −0.71 ± 0.13 |

| PreDM | 10 | −0.66 ± 0.19 | −1.55 ± 0.11 | −1.44 ± 0.14 | −0.80 ± 0.11 | −0.75 ± 0.12 |

| T2DM | 15 | −0.66 ± 0.10 | −1.40 ± 0.19 | −1.30 ± 0.12 | −0.69 ± 0.13 | −0.61 ± 0.11 |

| p = 0.972 | p = 0.074 | p = 0.091 | p = 0.257 | p = 0.013 | ||

| F = 0.028 | F = 2.792 | F = 2.560 | F = 1.413 | F = 4.888 |

| Group | N | Mars Contrast Sensitivity (log CS) | L’Anthony D-15 (CCI) | Lens Grading (LOCS III Scale) | Subjects with Retinopathy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 15 | 1.73 ± 0.08 | 1.20 ± 0.38 | 1.20 ± 0.26 | 0 |

| PreDM | 10 | 1.74 ± 0.09 | 1.11 ± 0.14 | 1.40 ± 0.33 | 0 |

| T2DM | 15 | 1.74 ± 0.05 | 1.32 ± 0.29 | 1.42 ± 0.36 | 1 with mild NPDR |

| p = 0.924 | p = 0.263 | p = 0.247 | |||

| F = 0.079 | F = 1.385 | F = 1.476 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burhans, L.; Owusu-Afriyie, B.; Wu, C.S.; Smith, J.D.; Coates, D.R.; Harrison, W.W. Exploring the Relationship Between Health Biomarkers and Performance on a Novel Color Perimetry Device in Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetology 2025, 6, 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120147

Burhans L, Owusu-Afriyie B, Wu CS, Smith JD, Coates DR, Harrison WW. Exploring the Relationship Between Health Biomarkers and Performance on a Novel Color Perimetry Device in Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetology. 2025; 6(12):147. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120147

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurhans, Liam, Bismark Owusu-Afriyie, Christopher S. Wu, Jennyffer D. Smith, Daniel R. Coates, and Wendy W. Harrison. 2025. "Exploring the Relationship Between Health Biomarkers and Performance on a Novel Color Perimetry Device in Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes" Diabetology 6, no. 12: 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120147

APA StyleBurhans, L., Owusu-Afriyie, B., Wu, C. S., Smith, J. D., Coates, D. R., & Harrison, W. W. (2025). Exploring the Relationship Between Health Biomarkers and Performance on a Novel Color Perimetry Device in Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetology, 6(12), 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120147