How the Salutogenic Pattern of Health Reflects in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

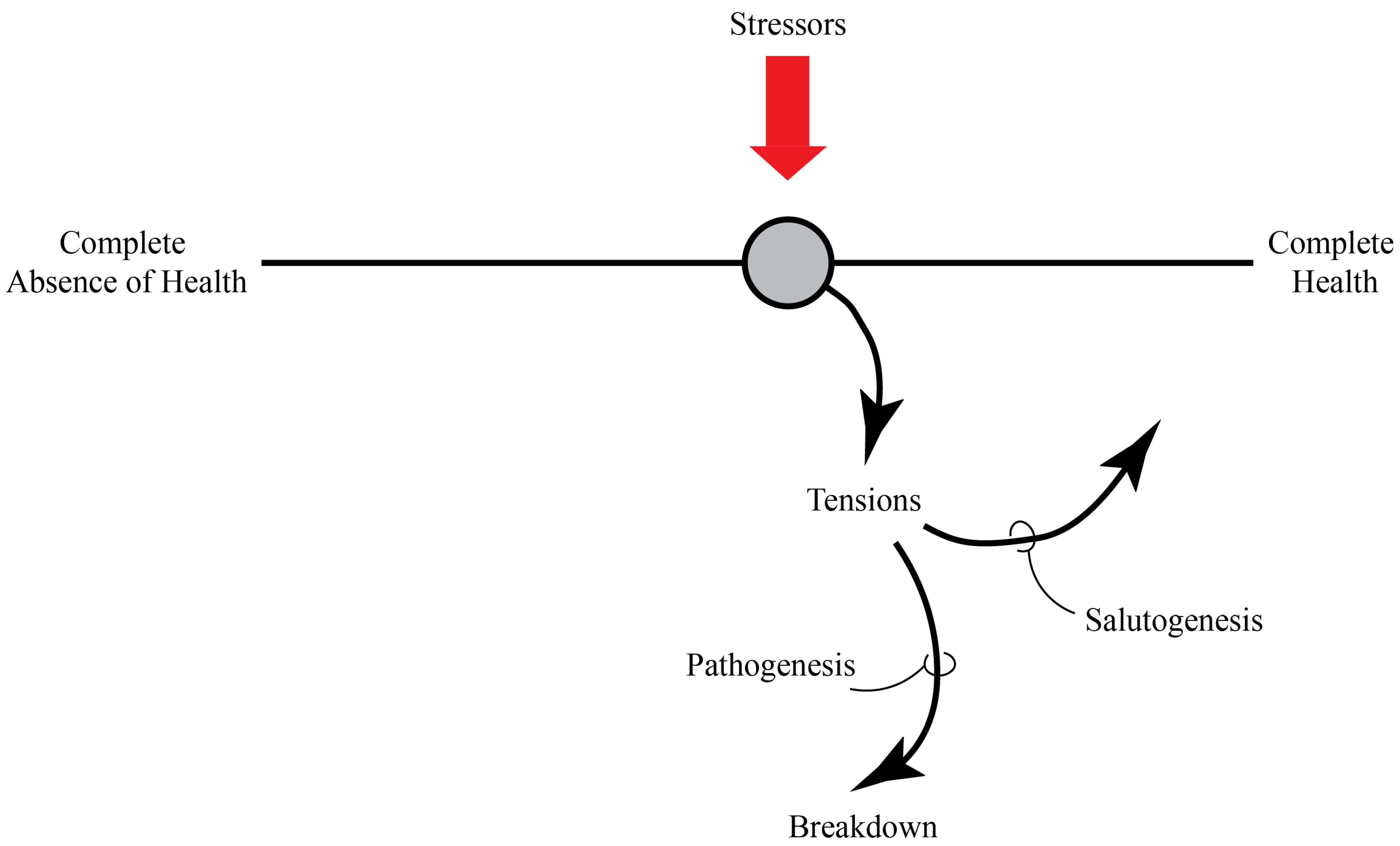

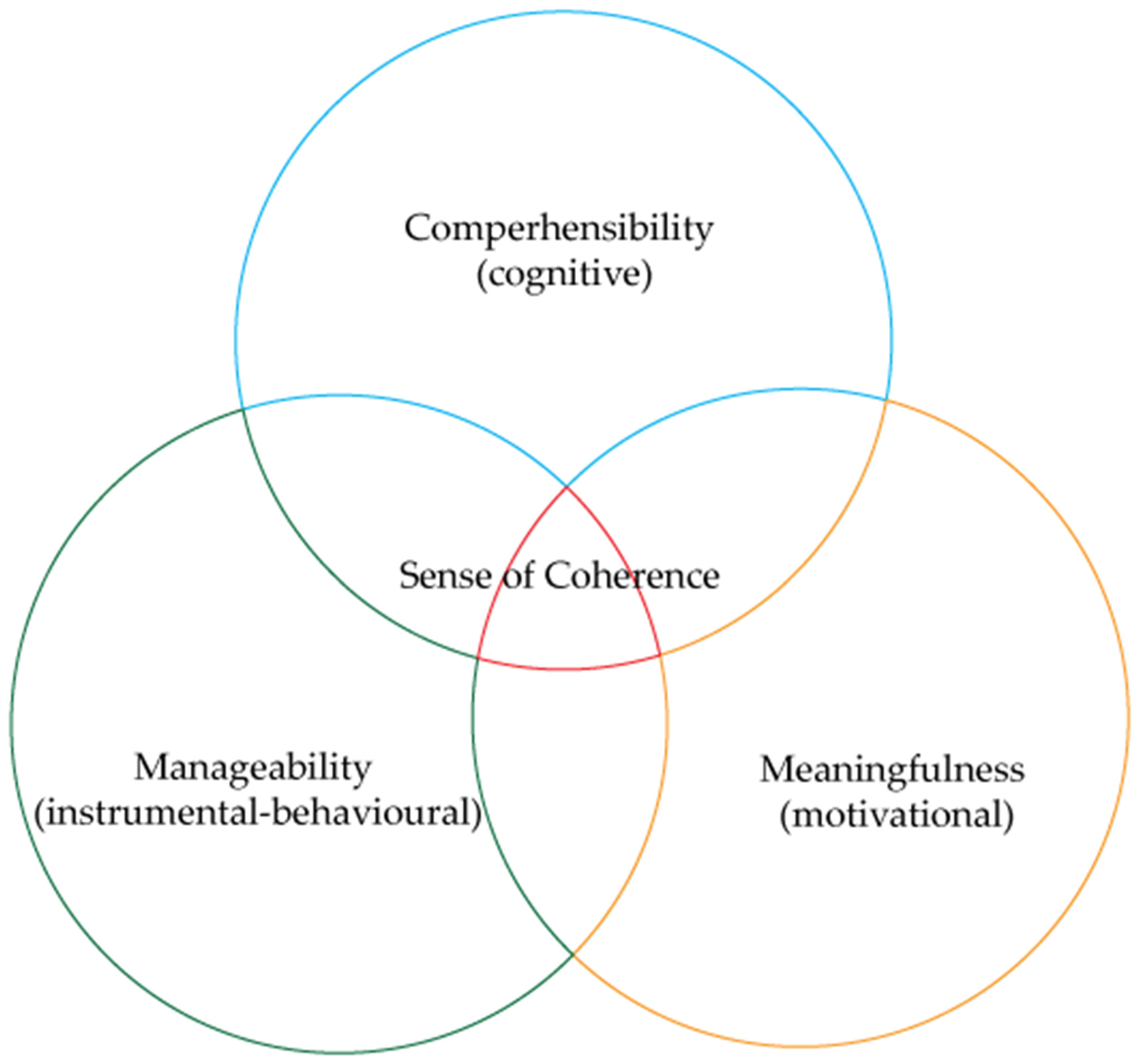

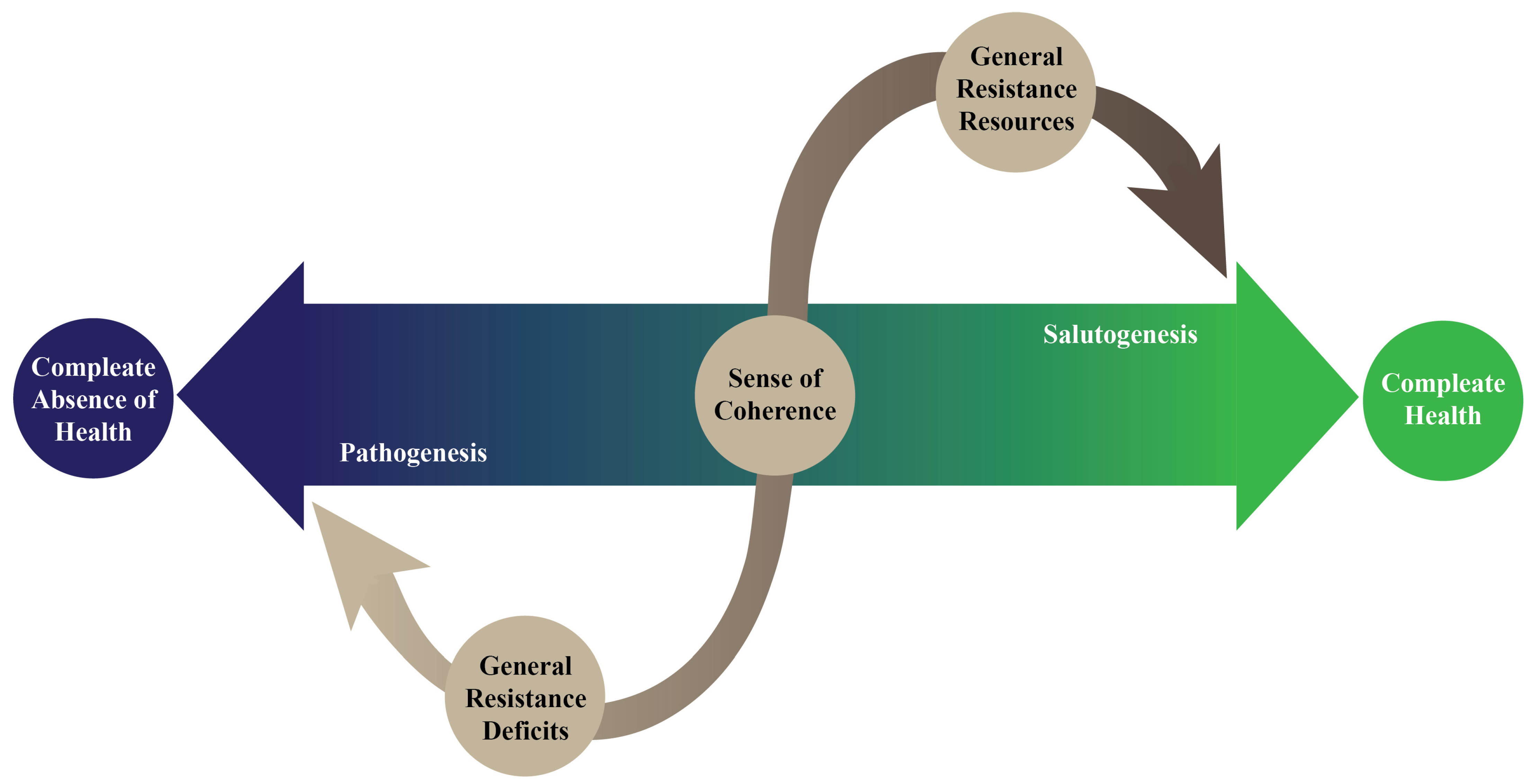

3. Health and the Salutogenic Pattern of Health

4. The Modern Concept of Health and Disease

5. The Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Salutogenic Pattern of Health

6. The Effects of Salutogenic Pattern of Health in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

7. The Background of the Positive Effects of the Salutogenic Pattern of Health in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

8. The Salutogenic Pattern of Health and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: The Way to Better Health

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ± | plus-minus sign |

| % | percentage |

| BE | Kingdom of Belgium |

| BMI | body mass index |

| CH | Swiss Confederation |

| DE | Federal Republic of Germany |

| DM | diabetes mellitus |

| DSQLS | Diabetes Specific Quality of Life Scale |

| EMBASE | Excerpta Medica database |

| EPSOC-2DM | Educational Program to Enhance Sense of Coherence in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 |

| et al. | and others (lat. et alia) |

| FPG | fasting plasma glucose |

| GB | United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland |

| GDM | gestational diabetes mellitus |

| HbA1c | glycohaemoglobin |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance |

| IDF | International Diabetes Federation |

| lat. | Latin |

| LDL-C | low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| MEDLINE | Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online |

| n | sample size |

| NL | Kingdom of the Netherlands |

| OLQ | Orientation to Life Questionnaire |

| PROs | patient-reported outcomes |

| Q&A | Questions and Answers |

| RCT | randomised controlled trial |

| ROC | receiver operating characteristic |

| SD | standard deviation |

| SALUD | Salutogenic intervention for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| SOC | sense of coherence |

| T1DM | type 1 diabetes mellitus |

| T2DM | type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| T5DM | type 5 diabetes mellitus |

| T-score | transformed standard score |

| USD | United States dollar |

| Z-score | standard score |

References

- Gudoor, R.; Suits, A.; Shubrook, J.H. Perfecting the Puzzle of Pathophysiology: Exploring Combination Therapy in the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetology 2023, 4, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristo, A.S.; İzler, K.; Grosskopf, L.; Kerns, J.J.; Sikalidis, A.K. Emotional Eating Is Associated with T2DM in an Urban Turkish Population: A Pilot Study Utilizing Social Media. Diabetology 2024, 5, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraco, G.; Gaspar, J.M. The Role of Adenosine Signaling in Obesity-Driven Type 2 Diabetes: Revisiting Mechanisms and Implications for Metabolic Regulation. Diabetology 2025, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Test, B.; Shubrook, J.H. Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes: The Role of Intermittent Fasting. Diabetology 2023, 4, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A.; Cornaby, L.; Ferrara, G.; Salama, J.S.; Mullany, E.C.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abebe, Z.; et al. Health Effects of Dietary Risks in 195 Countries, 1990–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polhuis, C.M.M.; Vaandrager, L.; Soedamah-Muthu, S.S.; Koelen, M.A. Salutogenic Model of Health to Identify Turning Points and Coping Styles for Eating Practices in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomás, A.; Fernandes, T.; Loureiro, H. Eating Disorders in Young Adults and Adults with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetology 2025, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattei, J.; Malik, V.; Wedick, N.M.; Hu, F.B.; Spiegelman, D.; Willett, W.C.; Campos, H.; Global Nutrition Epidemiologic Transition Initiative. Reducing the Global Burden of Type 2 Diabetes by Improving the Quality of Staple Foods: The Global Nutrition and Epidemiologic Transition Initiative. Glob. Health 2015, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cangelosi, G.; Mancin, S.; Pantanetti, P.; Nguyen, C.T.T.; Morales Palomares, S.; Biondini, F.; Sguanci, M.; Petrelli, F. Lifestyle Medicine Case Manager Nurses for Type Two Diabetes Patients: An Overview of a Job Description Framework—A Narrative Review. Diabetology 2024, 5, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Feng, L.; Song, P.; Wang, L.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.; Zhu, D.; Du, Y.; Leng, J. Joint Association of Overweight/Obesity, High Electronic Screen Time, and Low Physical Activity Time with Early Pubertal Development in Girls: A Case–Control Study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, G.N.; Manole, F.; Buleu, F.; Motofelea, A.C.; Bircea, S.; Popa, D.; Motofelea, N.; Pirvu, C.A. Bridging the Gap: A Literature Review of Advancements in Obesity and Diabetes Mellitus Management. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Mohammed, R.A. Obesity: Prevalence, Causes, Consequences, Management, Preventive Strategies and Future Research Directions. Metab. Open 2025, 27, 100375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.C.N.; Mbanya, J.C.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, Regional and Country-Level Diabetes Prevalence Estimates for 2021 and Projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charytonowicz, J.; Falcão, C. (Eds.) Advances in Human Factors in Architecture, Sustainable Urban Planning and Infrastructure; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmet, P.Z. Diabetes and Its Drivers: The Largest Epidemic in Human History? Clin. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuschieri, S.; Vassallo, J.; Calleja, N.; Pace, N.; Abela, J.; Ali, B.A.; Abdullah, F.; Zahra, E.; Mamo, J. The Diabesity Health Economic Crisis—The Size of the Crisis in a European Island State Following a Cross-Sectional Study. Arch. Public Health 2016, 74, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asong, J.A.; Ndhlovu, P.T.; Olatunde, A.; Aremu, A.O. Uses of African Plants and Associated Indigenous Knowledge for the Management of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetology 2024, 5, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundkvist, P.; Fjellström, C.; Sidenvall, B.; Lumbers, M.; Raats, M.; Food in Later life Team. Management of Healthy Eating in Everyday Life Among Senior Europeans. Appetite 2010, 55, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, B.; Usman, D.; Sanusi, K.O.; Azmi, N.H.; Imam, M.U. Preventive Epigenetic Mechanisms of Functional Foods for Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetology 2023, 4, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisogni, C.A.; Jastran, M.; Seligson, M.; Thompson, A. How People Interpret Healthy Eating: Contributions of Qualitative Research. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 282–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, C.M.; Wolfe, W.S.; Frongillo, E.A.; Bisogni, C.A. Life-Course Events and Experiences: Association with Fruit and Vegetable Consumption in 3 Ethnic Groups. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1999, 99, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinther, J.L.; Conklin, A.I.; Wareham, N.J.; Monsivais, P. Marital Transitions and Associated Changes in Fruit and Vegetable Intake: Findings from the Population-Based Prospective EPIC-Norfolk Cohort, UK. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 157, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, K.; Lončarek, K.; Slivšek, G. How Do Changes in the Family Structure and Dynamics Reflect on Health: The Socio-Ecological Model of Health in the Family. Med. Flum. 2024, 60, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Moya, I.; Morgan, A. The Utility of Salutogenesis for Guiding Health Promotion: The Case for Young People’s Well-Being. Health Promot. Int. 2017, 32, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. The Salutogenic Model as a Theory to Guide Health Promotion. Health Promot. Int. 1996, 11, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J.F.; Lae, L. Sense of Coherence, Well-Being, Coping and Personality Factors Further Evaluation of the Sense of Coherence Scale. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2002, 33, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvonen, A.M.; Väänänen, A.; Woods, S.A.; Heponiemi, T.; Koskinen, A.; Toppinen-Tanner, S. Sense of Coherence and Diabetes: A Prospective Occupational Cohort Study. BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, S.; Ng, E.D. Use of Salutogenic Approach Among Children and Adolescents with Chronic Illnesses: A Scoping Review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 56, e7–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelmark, M.B.; Bauer, G.F.; Vaandrager, L.; Pelikan, J.M.; Sagy, S.; Eriksson, M.; Lindström, B.; Meier Magistretti, C. (Eds.) The Handbook of Salutogenesis, 2nd ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, M.; Lindström, B. Antonovsky’s Sense of Coherence Scale and the Relation with Health: A Systematic Review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara C., M.S.; Nicolalde, M.; Amoroso, A.; Chico, P.; Mora, N.; Heredia, S.; Robalino, F.; Gonzalez, G. Association Between Sense of Coherence and Metabolic Control in People with Diabetes Mellitus Type 2. Eur. Sci. J. 2018, 14, 1857–7881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Márquez-Palacios, J.H.; Yanez-Peñúñuri, L.Y.; Salazar-Estrada, J.G. Relationship Between Sense of Coherence and Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review. Cien. Saude Colet. 2020, 25, 3955–3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.; Buschur, E.; Harris, C.; Pennell, M.L.; Soliman, A.; Wyne, K.; Dungan, K.M. Influence of Literacy, Self-Efficacy, and Social Support on Diabetes-Related Outcomes Following Hospital Discharge. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2022, 15, 2323–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Super, S.; Wagemakers, M.A.E.; Picavet, H.S.J.; Verkooijen, K.T.; Koelen, M.A. Strengthening Sense of Coherence: Opportunities for Theory Building in Health Promotion. Health Promot. Int. 2016, 31, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konaszewski, K.; Kolemba, M.; Niesiobędzka, M. Resilience, Sense of Coherence and Self-Efficacy as Predictors of Stress Coping Style Among University Students. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 4052–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparyan, A.Y.; Ayvazyan, L.; Blackmore, H.; Kitas, G.D. Writing a Narrative Biomedical Review: Considerations for Authors, Peer Reviewers, and Editors. Rheumatol. Int. 2011, 31, 1409–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhera, J. Narrative Reviews: Flexible, Rigorous, and Practical. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022, 14, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, L.; Amos, M.; Munro, J. (Eds.) Promoting Health: Politics and Practice; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, B. How to Draw the Line Between Health and Disease? Start with Suffering. Health Care Anal. 2021, 29, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramme, T. Health as Complete Well-Being: The WHO Definition and Beyond. Public Health Ethics 2023, 20, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartorius, N. The Meanings of Health and Its Promotion. Croat. Med. J. 2006, 47, 662–664. [Google Scholar]

- Green, A.R.; Carrillo, J.E.; Betancourt, J.R. Why the Disease-Based Model of Medicine Fails Our Patients. West. J. Med. 2002, 176, 141–143. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, R.; Reid, C.; Kloer, P.; Henchie, A.; Thomas, A.; Zwiggelaar, R. A Systematic Review of Literature Examining the Application of a Social Model of Health and Wellbeing. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 34, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, B.; Eriksson, M. Contextualizing Salutogenesis and Antonovsky in Public Health Development. Health Promot. Int. 2006, 21, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Pradhan, K.; Bashar, M.; Tripathi, S.; Thiyagarajan, A.; Srivastava, A.; Singh, A. Salutogenesis: A Bona Fide Guide towards Health Preservation. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Vaandrager, L.; Lindström, B. (Eds.) The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Salutogenesis, 2nd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Shmarina, E.; Ericson, D.; Åkerman, S.; Axtelius, B. Salutogenic Factors for Oral Health Among Older People: An Integrative Review Connecting the Theoretical Frameworks of Antonovsky and Lalonde. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2021, 79, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochwälder, J. Sense of Coherence: Notes on Some Challenges for Future Research. SAGE Open 2019, 9, 2158244019846687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Eriksson, M.; Wengström, Y.; Czene, K.; Hall, P.; Fang, F. Sense of Coherence and Risk of Breast Cancer. Elife 2020, 9, e61469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streiner, D.L.; Norman, G.R.; Cairney, J. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use, 6th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, I.; Fagerberg, B.; Lundman, B. Health-Related Quality of Life and Sense of Coherence Among Elderly Patients with Severe Chronic Heart Failure in Comparison with Healthy Controls. Heart Lung J. Cardiopulm. Acute Care 2002, 31, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohani, C.; Abedi, H.-A.; Sundberg, K.; Langius-Eklöf, A. Sense of Coherence as a Mediator of Health-Related Quality of Life Dimensions in Patients with Breast Cancer: A Longitudinal Study with Prospective Design. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2015, 13, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziuba, A.; Krell-Roesch, J.; Schmidt, S.C.E.; Bös, K.; Woll, A. Association Between Sense of Coherence and Health Outcomes at 10 and 20 Years Follow-up: A Population-Based Longitudinal Study in Germany. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 739394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malagon-Aguilera, M.C.; Suñer-Soler, R.; Bonmatí-Tomas, A.; Bosch-Farré, C.; Gelabert-Vilella, S.; Juvinyà-Canal, D. Relationship Between Sense of Coherence, Health and Work Engagement Among Nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 1620–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke, A.; Conrad, D.; Kolassa, I.-T.; Rojas, R. Higher Sense of Coherence Is Associated with Better Mental and Physical Health in Emergency Medical Services: Results from Investigations on The Revised Sense of Coherence Scale (SOC-R) in Rescue Workers. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2019, 10, 1606628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xu, Z.; He, X.; Zhang, J.; Song, R.; Duan, W.; Liu, T.; Yang, H. Sense of Coherence and Mental Health in College Students after Returning to School During COVID-19: The Moderating Role of Media Exposure. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 687928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da-Silva-Domingues, H.; Del-Pino-Casado, R.; Palomino-Moral, P.Á.; López Martínez, C.; Moreno-Cámara, S.; Frías-Osuna, A. Relationship Between Sense of Coherence and Health-Related Behaviours in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletta, M.; Cherchi, M.; Cocco, A.; Lai, G.; Manca, V.; Pau, M.; Tatti, F.; Zambon, G.; Deidda, S.; Origa, P.; et al. Sense of Coherence and Physical Health-Related Quality of Life in Italian Chronic Patients: The Mediating Role of the Mental Component. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e030001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Siles, P.; Martí-Vilar, M.; González-Sala, F.; Merino-Soto, C.; Toledano-Toledano, F. Sense of Coherence and Work Stress or Well-Being in Care Professionals: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piiroinen, I.; Tuomainen, T.-P.; Tolmunen, T.; Kauhanen, J.; Kurl, S.; Nilsen, C.; Suominen, S.; Välimäki, T.; Voutilainen, A. Long-Term Changes in Sense of Coherence and Mortality Among Middle-Aged Men: A Population-Based Follow-up Study. Adv. Life Course Res. 2022, 53, 100494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakershahrak, M.; Chrisopoulos, S.; Luzzi, L.; Jamieson, L.; Brennan, D. Income and Oral and General Health-Related Quality of Life: The Modifying Effect of Sense of Coherence, Findings of a Cross-Sectional Study. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2023, 18, 2561–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, J.F.; Langeland, E.; Ness, O.; Skogvang, B.O. Experiences of the Quality of the Interplay Between Home-Living Young Adults with Serious Mental Illness and Their Social Environments. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 44, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Montayre, J.; Koduah, A.O.; Leung, A.Y.M. Non-pharmacological Interventions Targeting Sense of Coherence Among Older Adults and Adults with Chronic Conditions: A Meta-analysis with Trial Sequential Analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025, 81, 2165–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.S.F.; Cheng, S.-T.; Chow, E.O.-W.; Kwok, T.; McCormack, B.; Wu, W. The Effects of a Salutogenic Strength-Based Intervention on Sense of Coherence and Health Outcomes of Dementia Family Carers: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Age Ageing 2023, 52, afad160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Deng, M.; Yu, M. Interventions Based on Salutogenesis for Older Adults: An Integrative Review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 2456–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Jiang, Q.; Ye, F.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Zhai, M. The Effects of a Salutogenic Strength-Based Intervention on Sense of Coherence and Health Outcomes in Newly Diagnosed HIV-Positive MSM: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2025, 165, 105036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, L.-H.; Zeng, H.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, Y.-Q.; Zhang, T.-Y.; Luo, H.-B.; Tang, F. Psychological Consistency Network Characteristics and Influencing Factors in Patients after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Treatment. World J. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 102571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portoghese, I.; Sardu, C.; Bauer, G.; Galletta, M.; Castaldi, S.; Nichetti, E.; Petrocelli, L.; Tassini, M.; Tidone, E.; Mereu, A.; et al. A Network Perspective to the Measurement of Sense of Coherence (SOC): An Exploratory Graph Analysis Approach. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 16624–16636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieraité, M.; Novoselac, A.; Bättig, J.J.; Rühlmann, C.; Bentz, D.; Noboa, V.; Seifritz, E.; Egger, S.T.; Weidt, S. Relationship Between Sense of Coherence and Depression, a Network Analysis. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 23295–23303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeang, K.; Dilani, A. (Eds.) Ecological and Salutogenic Design for a Sustainable Healthy Global Society; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tekin, B.H.; Izmir Tunahan, G.; Disci, Z.N.; Ozer, H.S. Biophilic Design in the Built Environment: Trends, Gaps and Future Directions. Buildings 2025, 15, 2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akankwatsa, K.P.; Kasozi, P.; Shema, A.I. Assessment of Sense of Coherence (Salutogenesis in Built Environment) in Mental Health Hospitals Space. A Comparative Assessment. Des. Health 2025, 9, 60–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoma, A.; Eaves, F.F. A Brief History of Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) and the Contributions of Dr David Sackett. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2015, 35, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, S.; Baruah, M.P.; Sahay, R. Salutogenesis in Type 2 Diabetes Care: A Biopsychosocial Perspective. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 22, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, D.M. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Study at 30 Years: Overview. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, H.; Jacobs, D.R. The University Group Diabetes Program 1961–1978: Pioneering Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1354–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinert, C. The Trials and Tribulations of the University Group Diabetes Program 1: The Trial and the Controversies. J. R. Soc. Med. 2019, 112, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meinert, C. The Trials and Tribulations of the University Group Diabetes Program 2: Lessons and Reflections. J. R. Soc. Med. 2019, 112, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.L. The Clinical Application of the Biopsychosocial Model. Am. J. Psychiatry 1980, 137, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolton, D.; Gillett, G. The Biopsychosocial Model of Health and Disease; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Borrell-Carrió, F.; Suchman, A.L.; Epstein, R.M. The Biopsychosocial Model 25 Years Later: Principles, Practice, and Scientific Inquiry. Ann. Fam. Med. 2004, 2, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis Turabian, J. Patient-Centered Care and Biopsychosocial Model. Trends Gen. Pract. 2018, 1, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, B.J.; David, D.M.; Gruber, J.A. Rethinking the Biopsychosocial Model of Health: Understanding Health as a Dynamic System. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2017, 11, e12328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelmark, M.B.; Bull, T. The Salutogenic Model of Health in Health Promotion Research. Glob. Health Promot. 2013, 20, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed, S.; Syed, S.; Bhardwaj, K. The Role of the Bio-Psychosocial Model in Public Health. J. Med. Res. 2020, 6, 252–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoete, V.; Meuwly, M.; Karplus, M. A Comparison of the Dynamic Behavior of Monomeric and Dimeric Insulin Shows Structural Rearrangements in the Active Monomer. J. Mol. Biol. 2004, 342, 913–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, D.F. Adventures with Insulin in the Islets of Langerhans. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 17399–17421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszewski, W.; Baranowska-Jurkun, A.; Stefanowicz-Rutkowska, M.M.; Modzelewski, R.; Pieczyński, J.; Bandurska-Stankiewicz, E. Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients in North-East Poland. Medicina 2020, 56, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magliano, D.J.; Boyko, E.J.; Genitsaridi, I.; Piemonte, L.; Riley, P.; Salpea, P. (Eds.) IDF Diabetes Atlas, 11th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sknepnek, A.; Miletić, D.; Stupar, A.; Salević-Jelić, A.; Nedović, V.; Cvetanović Kljakić, A. Natural Solutions for Diabetes: The Therapeutic Potential of Plants and Mushrooms. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1511049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dube, R.; Bambani, T.; Saif, S.; Hashmi, N.; Patni, M.A.M.F.; Kedia, N.R. The Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Polycystic Ovary Disease—A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Exploration of Associated Risk Factors. Diabetology 2024, 5, 430–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, S. Type 5 Diabetes Mellitus: Global Recognition of a Previously Overlooked Subtype. Bangladesh J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 4, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K.; et al. Global and Regional Diabetes Prevalence Estimates for 2019 and Projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th Edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trikkalinou, A.; Papazafiropoulou, A.K.; Melidonis, A. Type 2 Diabetes and Quality of Life. World J. Diabetes 2017, 8, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galicia-Garcia, U.; Benito-Vicente, A.; Jebari, S.; Larrea-Sebal, A.; Siddiqi, H.; Uribe, K.B.; Ostolaza, H.; Martín, C. Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voseckova, A.; Truhlarova, Z.; Levicka, J.; Klimova, B.; Kuca, K. Application of Salutogenic Concept in Social Work with Diabetic Patients. Soc. Work Health Care 2017, 56, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesavadev, J.; Saboo, B.; Sadikot, S.; Das, A.K.; Joshi, S.; Chawla, R.; Thacker, H.; Shankar, A.; Ramachandran, L.; Kalra, S. Unproven Therapies for Diabetes and Their Implications. Adv. Ther. 2017, 34, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, H.; Hasan, H.; Hamadeh, R.; Hashim, M.; AbdulWahid, Z.; Hassanzadeh Gerashi, M.; Al Hilali, M.; Naja, F. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Living in the United Arab Emirates. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiyorini, E.; Qomaruddin, M.B.; Wibisono, S.; Juwariah, T.; Setyowati, A.; Wulandari, N.A.; Sari, Y.K.; Sari, L.T. Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Glycemic Control of Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review. J. Public Health Res. 2022, 11, 22799036221106582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzuca, S.A. Does Patient Education in Chronic Disease Have Therapeutic Value? J. Chronic Dis. 1982, 35, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, S.; Unnikrishnan, A.; Skovlund, S. Patient Empowerment in Endocrinology. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 16, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hapunda, G. Coping Strategies and Their Association with Diabetes Specific Distress, Depression and Diabetes Self-Care Among People Living with Diabetes in Zambia. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2022, 22, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshete, A.; Mohammed, S.; Deresse, T.; Kifleyohans, T.; Assefa, Y. Association of Stress Management Behavior and Diabetic Self-Care Practice Among Diabetes Type II Patients in North Shoa Zone: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M. The Prevention and Control the Type-2 Diabetes by Changing Lifestyle and Dietary Pattern. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2014, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galaviz, K.I.; Narayan, K.M.V.; Lobelo, F.; Weber, M.B. Lifestyle and the Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes: A Status Report. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2018, 12, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, R.E.; Schriever, S.C.; Pfluger, P.T. Physiological and Epigenetic Features of Yoyo Dieting and Weight Control. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odajima, Y.; Kawaharada, M.; Wada, N. Development and Validation of an Educational Program to Enhance Sense of Coherence in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Type 2. Nagoya J. Med. Sci. 2017, 79, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polhuis, K. Flourish and Nourish: Development and Evaluation of a Salutogenic Healthy Eating Programme for People with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus; Wageningen University & Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Polhuis, K.C.M.M.; Koelen, M.A.; Bouwman, L.I.; Vaandrager, L. Qualitative Evaluation of a Salutogenic Healthy Eating Programme for Dutch People with Type 2 Diabetes. Health Promot. Int. 2023, 38, daad170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis, A.M.; Johnson, M.H.; Cutfield, R.G.; Consedine, N.S. Kindness Matters: A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Mindful Self-Compassion Intervention Improves Depression, Distress, and HbA1c Among Patients with Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 1963–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polhuis, C.M.M.; Bouwman, L.I.; Vaandrager, L.; Soedamah-Muthu, S.S.; Koelen, M.A. Systematic Review of Salutogenic-Oriented Lifestyle Randomised Controlled Trials for Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 764–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ee, C.C.; Al-Kanini, I.; Armour, M.; Piya, M.K.; McMorrow, R.; Rao, V.S.; Naidoo, D.; Metzendorf, M.-I.; Kroeger, C.M.; Sabag, A. Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Integr. Med. Res. 2025, 14, 101138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, A.-K.; van den Donk, M.; Hilding, A.; Östenson, C.-G. Work Stress, Sense of Coherence, and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in a Prospective Study of Middle-Aged Swedish Men and Women. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 2683–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.; Kanter, Y. Relation Between Sense of Coherence and Glycemic Control in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes. Behav. Med. 2004, 29, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahola, A.J.; Saraheimo, M.; Forsblom, C.; Hietala, K.; Groop, P.-H. The Cross-Sectional Associations Between Sense of Coherence and Diabetic Microvascular Complications, Glycaemic Control, and Patients’ Conceptions of Type 1 Diabetes. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, K.; Jensen, T.M.; Diaz, L.J.; Møller, A.C.L.; Willaing, I.; Lyssenko, V. Sense of Coherence Is Associated with LDL-Cholesterol in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes—The PROLONG-Steno Study. J. Clin. Transl. Endocrinol. 2017, 8, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, N.W.J.; Surtees, P.G.; Welch, A.A.; Luben, R.N.; Khaw, K.-T.; Bingham, S.A. Healthy Lifestyle Choices: Could Sense of Coherence Aid Health Promotion? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, N.W.J.; Surtees, P.G.; Welch, A.A.; Luben, R.N.; Khaw, K.-T.; Bingham, S.A. Sense of Coherence, Lifestyle Choices and Mortality. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2008, 62, 829–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahola, A.J.; Mikkilä, V.; Saraheimo, M.; Wadén, J.; MäkimaTtila, S.; Forsblom, C.; Freese, R.; Groop, P.-H. Sense of Coherence, Food Selection and Leisure Time Physical Activity in Type 1 Diabetes. Scand. J. Public Health 2012, 40, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakizadeh, E.; Hafezi, F. Sense of Coherence as a Predictor of Quality of Life Among Iranian Students Living in Ahvaz. Oman Med. J. 2015, 30, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Valle, D.; García-Cortés, L.R.; de Los Ángeles Dichi-Romero, M. Sense of Coherence in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Debutants: Case-Control Study. Rev. Med. Inst. Mex. Seguro Soc. 2023, 61, 258–264. [Google Scholar]

- Agardh, E.E.; Ahlbom, A.; Andersson, T.; Efendic, S.; Grill, V.; Hallqvist, J.; Norman, A.; Östenson, C.-G. Work Stress and Low Sense of Coherence Is Associated with Type 2 Diabetes in Middle-Aged Swedish Women. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Madhu, S.V.; Siddiqui, A.; Desai, N.G.; Sharma, S.B.; Bansal, A.K. Chronic Stress, Sense of Coherence and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2019, 13, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuccitelli, C.; Valentini, A.; Caletti, M.T.; Caselli, C.; Mazzella, N.; Forlani, G.; Marchesini, G. Sense of Coherence, Self-Esteem, and Health Locus of Control in Subjects with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus with/without Satisfactory Metabolic Control. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2018, 41, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, V.; Bakke, P.S.; Rohde, G.; Gallefoss, F. Is Sense of Coherence a Predictor of Lifestyle Changes in Subjects at Risk for Type 2 Diabetes? Public Health 2015, 129, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Martínez, M.D.C.; López-Martínez, C.; Del-Pino-Casado, R. Sense of Coherence and Adherence to Self-Care in People with Diabetes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kordbagheri, M.; Bagheri, S.M.; Heris, N.J.; Matbouraftar, P.; Azarian, M.; Mousavi, S.M. The Mediating Role of Psychological Well-Being in the Relationship Between the Light Triad of Personality and Sense of Concordance with Treatment Adherence in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Network Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling Study. Acta Psychol. 2024, 248, 104361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.-Y.; Shiu, A.T.-Y. Sense of Coherence and Diabetes-specific Stress Perceptions of Diabetic Patients in Central Mainland China. J. Clin. Nurs. 2006, 15, 1460–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiu, A.T.-Y. Sense of Coherence Amongst Hong Kong Chinese Adults with Insulin-Treated Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2004, 41, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, M.; Elkonin, D.; Brown, O. Sense of Coherence and Quality of Life in Elderly Persons Living with Diabetes Mellitus: An Exploratory Study. J. Psychol. Africa 2012, 22, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, T.; Okada, H.; Hamaguchi, M.; Kurogi, K.; Murata, H.; Ito, M.; Fukui, M. Estimated Small Dense Low-Density Lipoprotein-Cholesterol and Incident Type 2 Diabetes in Japanese People: Population-Based Panasonic Cohort Study 13. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 199, 110665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Lin, H.; Wang, S.; Li, M.; Wang, T.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, Y.; Xu, M.; Lu, J.; Chen, Y.; et al. Association Between Serum LDL-C Concentrations and Risk of Diabetes: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Diabetes 2023, 15, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandén-Eriksson, B. Coping with Type-2 Diabetes: The Role of Sense of Coherence Compared with Active Management. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 31, 1393–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odajima, Y.; Sumi, N. Factors Related to Sense of Coherence in Adult Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Nagoya J. Med. Sci. 2018, 80, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diontama, M.A.; Larasati, T.; Jausal, A.N.; Lisiswanti, R. Effect of Disease Acceptance on Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Inform. Technol. 2025, 3, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merakou, K.; Koutsouri, A.; Antoniadou, E.; Barbouni, A.; Bertsias, A.; Karageorgos, G.; Lionis, C. Sense of Coherence in People with and without Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Observational Study from Greece. Ment. Health Fam. Med. 2013, 10, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hilding, A.; Eriksson, A.-K.; Agardh, E.E.; Grill, V.; Ahlbom, A.; Efendic, S.; Östenson, C.-G. The Impact of Family History of Diabetes and Lifestyle Factors on Abnormal Glucose Regulation in Middle-Aged Swedish Men and Women. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 2589–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelgadir, M.; Shebeika, W.; Eltom, M.; Berne, C.; Wikblad, K. Health Related Quality of Life and Sense of Coherence in Sudanese Diabetic Subjects with Lower Limb Amputation. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2009, 217, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindmark, U.; Stegmayr, B.; Nilsson, B.; Lindahl, B.; Johansson, I. Food Selection Associated with Sense of Coherence in Adults. Nutr. J. 2005, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silarova, B.; Nagyova, I.; Rosenberger, J.; Studencan, M.; Ondusova, D.; Reijneveld, S.A.; van Dijk, J.P. Sense of Coherence as a Predictor of Health-Related Behaviours Among Patients with Coronary Heart Disease. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2014, 13, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curyło, M.; Rynkiewicz-Andryśkiewicz, M.; Andryśkiewicz, P.; Mikos, M.; Lusina, D.; Raczkowski, J.W.; Juszczyk, G.; Kotwas, A.; Sygit, K.; Kmieć, K.; et al. The Sense of Coherence and Health Behavior of Men with Alcohol Addiction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, Y.; Ohta, M.; Inoue, T.; Honda, T.; Konno, Y.; Eguchi, Y.; Yamato, H. Sense of Coherence Is Significantly Associated with Both Metabolic Syndrome and Lifestyle in Japanese Computer Software Office Workers. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2014, 27, 967–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, L.; Mullan, J.T.; Arean, P.; Glasgow, R.E.; Hessler, D.; Masharani, U. Diabetes Distress but Not Clinical Depression or Depressive Symptoms Is Associated with Glycemic Control in Both Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Analyses. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, S.T.; Fransson, E.I.; Heikkilä, K.; Ahola, K.; Alfredsson, L.; Bjorner, J.B.; Borritz, M.; Burr, H.; Dragano, N.; Goldberg, M.; et al. Job Strain as a Risk Factor for Type 2 Diabetes: A Pooled Analysis of 124,808 Men and Women. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 2268–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellingrath, S. The Trials and Tribulations of Teaching: A Psychobiological Perspective on Chronic Work Stress in School Teachers; Cuvillier Verlag: Göttingen, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chittem, M.; Lindström, B.; Byrapaneni, R.; Espnes, G. Sense of Coherence and Chronic Illnesses: Scope for Research in India. J. Soc. Health Diabetes 2015, 3, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Zhang, N.; Pan, S.-J.; Zhao, P.; Wu, B.-W. Sense of Coherence and Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Brain Metastases. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dymecka, J.; Gerymski, R.; Tataruch, R.; Bidzan, M. Sense of Coherence and Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: The Role of Physical and Neurological Disability. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawma, T.; Sanjab, Y. The Association Between Sense of Coherence and Quality of Life: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Sample of Patients on Hemodialysis. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, H.; Meng, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, T. Factors Associated with Quality of Life Among Elderly Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: The Role of Family Caregivers. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, I.; Miksch, A.; Goetz, K.; Ose, D.; Szecsenyi, J.; Freund, T. The Impact of Perceived Social Support and Sense of Coherence on Health-Related Quality of Life in Multimorbid Primary Care Patients. Chronic Illn. 2012, 8, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, V.M.; de Araújo, G.L.; Lyra, M.C.A.; Rosenblatt, A.; Heimer, M.V. Sense of Coherence and Quality of Life in Adolescents with Heart Disease. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2022, 40, e2021104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gison, A.; Rizza, F.; Bonassi, S.; Dall’Armi, V.; Lisi, S.; Giaquinto, S. The Sense-of-Coherence Predicts Health-Related Quality of Life and Emotional Distress but Not Disability in Parkinson’s Disease. BMC Neurol. 2014, 14, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alyami, M.; Serlachius, A.; Mokhtar, I.; Broadbent, E. Illness Perceptions, HbA1c, and Adherence in Type 2 Diabetes in Saudi Arabia. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2019, 13, 1839–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-González, I.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Conrad, R.; Pérez-San-Gregorio, M.Á. Quality of Life in Adults with Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e041249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chantzaras, A.; Yfantopoulos, J. Association Between Medication Adherence and Health-Related Quality of Life of Patients with Diabetes. Hormones 2022, 21, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, A.; Schulte, T.; Ernst, J.; Mehnert-Theuerkauf, A.; Finck, C.; Wondie, Y.; Ernst, M. Sense of Coherence, Resilience, and Habitual Optimism in Cancer Patients. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2023, 23, 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conversano, C.; Di Giuseppe, M. Psychological Factors as Determinants of Chronic Conditions: Clinical and Psychodynamic Advances. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 635708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, R.G.; Rega, I.C.; López, M.A.R.; Díaz, M. del M.J. Salut Research Project 2.1 Sense of Coherence, Quality of Life and Metabolic Control in Diabetic Patients. Garnata 91 2020, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, K.; Akre, S.; Chakole, S.; Wanjari, M.B. Stress-Induced Diabetes: A Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e29142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sami, W.; Ansari, T.; Butt, N.S.; Hamid, M.R.A. Effect of Diet on Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Review. Int. J. Health Sci. 2017, 11, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Vela, A.M.; Palmer, B.; Gil-Rivas, V.; Cachelin, F. The Role of Disordered Eating in Type 2 Diabetes: A Pilot Study. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2023, 17, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, D.; He, J.; Li, Y.; Ouyang, F.; Xiao, S. Stressful Life Events, Unhealthy Eating Behaviors and Obesity Among Chinese Government Employees: A Follow-up Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betke, K.; Basińska, M.A.; Andruszkiewicz, A. Sense of Coherence and Strategies for Coping with Stress Among Nurses. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, A.; Madhu, S.V.; Sharma, S.B.; Desai, N.G. Endocrine Stress Responses and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Stress 2015, 18, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.Y.; Kim, E.; Choi, M.H. Technical and Clinical Aspects of Cortisol as a Biochemical Marker of Chronic Stress. BMB Rep. 2015, 48, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.A.M.J.L. New Insights into the Role of Insulin and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis in the Metabolic Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Mesgarani, A.; Karimipour, S.; Pasha, S.Z.; Kashi, Z.; Abedian, S.; Mousazadeh, M.; Molania, T. Comparison of Salivary Cortisol Level in Type 2 Diabetic Patients and Pre-Diabetics with Healthy People. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 2321–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schechter, C.B.; Walker, E.A. Improving Adherence to Diabetes Self-Management Recommendations. Diabetes Spectr. 2002, 15, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.S.; Shreck, E.; Psaros, C.; Safren, S.A. Distress and Type 2 Diabetes-Treatment Adherence: A Mediating Role for Perceived Control. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwani, S.I.; Khan, H.A.; Ekhzaimy, A.; Masood, A.; Sakharkar, M.K. Significance of HbA1c Test in Diagnosis and Prognosis of Diabetic Patients. Biomark. Insights 2016, 11, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, J.J.; Khan, M.H.; Jahn, H.J.; Kraemer, A. Sense of Coherence and Associated Factors Among University Students in China: Cross-Sectional Evidence. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patricia, C.-H.; Blanca, E.C.; Dolors, J.C. Sense of Coherence and Lifestyle in Young University Adults: Review. Nurs. Care Open Access J. 2018, 5, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, D. Sense of Coherence and Psychological Well-Being Among Coronary Heart Disease Patients: A Moderated Mediation Model of Affect and Meaning in Life. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 4828–4836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.; Adner, N.; Nordstrom, G. Persons with Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus: Acceptance and Coping Ability. J. Adv. Nurs. 2001, 33, 758–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, W.; Henry, R. Poor Medication Adherence in Type 2 Diabetes: Recognizing the Scope of the Problem and Its Key Contributors. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2016, 10, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, H.; Mizobe, M. Impact of Nonadherence on Complication Risks and Healthcare Costs in Patients Newly-Diagnosed with Diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 123, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerci, B.; Chanan, N.; Kaur, S.; Jasso-Mosqueda, J.G.; Lew, E. Lack of Treatment Persistence and Treatment Nonadherence as Barriers to Glycaemic Control in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2019, 10, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson, H.; Quennerstedt, M.; Geidne, S. Physical Activity as a Health Resource: A Cross-Sectional Survey Applying a Aalutogenic Approach to What Older Adults Consider Meaningful in Organised Physical Activity Initiatives. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2021, 9, 858–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adorni, R.; Greco, A.; D’Addario, M.; Zanatta, F.; Fattirolli, F.; Franzelli, C.; Maloberti, A.; Giannattasio, C.; Steca, P. Sense of Coherence Predicts Physical Activity Maintenance and Health-Related Quality of Life: A 3-Year Longitudinal Study on Cardiovascular Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z. Association Between Social Capital and Health-Promoting Lifestyle Among Empty Nesters: The Mediating Role of Sense of Coherence. Geriatr. Nurs. 2023, 53, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, J.P.C.; Wolfgram, E.; Batista de Souza, J.P.; Fausto Silva, L.G.; Estavien, Y.; de Almeida, R.; Pestana, C.R. Lifestyle and Sense of Coherence: A Comparative Analysis Among University Students in Different Areas of Knowledge. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhud, D.D. Impact of Lifestyle on Health. Iran. J. Public Health 2015, 44, 1442–1444. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, D.B.; Thayer, J.F.; Vedhara, K. Stress and Health: A Review of Psychobiological Processes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2021, 72, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Rocha, G.M.; López-Botello, C.K.; Salinas-Martínez, A.M.; Arroyo-Acevedo, H.V.; Martínez-Villarreal, R.T.; Ávila-Ortiz, M.N. Lifestyle, Quality of Life, and Health Promotion Needs in Mexican University Students: Important Differences by Sex and Academic Discipline. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilchez-Chavez, A.; Bernal Altamirano, E.; Morales-García, W.C.; Sairitupa-Sanchez, L.; Morales-García, S.B.; Saintila, J. Healthy Habits Factors and Stress Associated with Health-Related Quality of Life in a Peruvian Adult Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2023, 16, 2691–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgraf, R.; Aberle, J.; Birkenfeld, A.L.; Gallwitz, B.; Kellerer, M.; Klein, H.; Müller-Wieland, D.; Nauck, M.A.; Reuter, H.-M.; Siegel, E. Therapy of Type 2 Diabetes. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2019, 127, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, L.; Skaff, M.M.; Mullan, J.T.; Arean, P.; Glasgow, R.; Masharani, U. A Longitudinal Study of Affective and Anxiety Disorders, Depressive Affect and Diabetes Distress in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabet. Med. J. Br. Diabet. Assoc. 2008, 25, 1096–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, N.A. Type 2 Diabetes: Lifestyle Changes and Drug Treatment. AMA J. Ethics 2009, 11, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, S.; Kumar, S.; Kalra, B.; Unnikrishnan, A.; Agrawal, N.; Sahay, R. Patient-Provider Interaction in Diabetes: Minimizing the Discomfort of Change. Internet J. Fam. Pract. 2009, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rubeis, G.; Steger, F. Salutogenesis as Empowerment. Health Promotion and the Role of the Medical Humanities. Droit Santé Soc. 2019, 2, 75–83. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Kalra, S.; Sridhar, G.; Balhara, Y.P.; Sahay, R.; Bantwal, G.; Baruah, M.; John, M.; Unnikrishnan, A.; Madhu, K.; Verma, K.; et al. National Recommendations: Psychosocial Management of Diabetes in India. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 17, 376–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaskara, G.; Budhiarta, A.A.G.; Gotera, W.; Saraswati, M.R.; Dwipayana, I.M.P.; Semadi, I.M.S.; Nugraha, I.B.A.; Wardani, I.A.K.; Suastika, K. Factors Associated with Diabetes-Related Distress in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2022, 15, 2077–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, M.A.; Theeke, L.A. A Systematic Review of the Relationships Among Psychosocial Factors and Coping in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 6, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speight, J.; Browne, J.L.; Holmes-Truscott, E.; Hendrieckx, C.; Pouwer, F. Diabetes MILES-Australia (Management and Impact for Long-Term Empowerment and Success): Methods and Sample Characteristics of a National Survey of the Psychological Aspects of Living with Type 1 or Type 2 Diabetes in Australian Adults. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.H.; Parsons, J.A.; Mamdani, M.; Lebovic, G.; Hall, S.; Newton, D.; Shah, B.R.; Bhattacharyya, O.; Laupacis, A.; Straus, S.E. A Web-Based Intervention to Support Self-Management of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Effect on Self-Efficacy, Self-Care and Diabetes Distress. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2014, 14, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitebird, R.R.; Kreitzer, M.J.; Vazquez-Benitez, G.; Enstad, C.J. Reducing Diabetes Distress and Improving Self-Management with Mindfulness. Soc. Work Health Care 2018, 57, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilliard, M.E.; Oser, S.M.; Close, K.L.; Liu, N.F.; Hood, K.K.; Anderson, B.J. From Individuals to International Policy: Achievements and Ongoing Needs in Diabetes Advocacy. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2015, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkisson, S.; Pillay, B.J.; Sibanda, W. Social Support and Coping in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. African J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2017, 9, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uusitupa, M.; Khan, T.A.; Viguiliouk, E.; Kahleova, H.; Rivellese, A.A.; Hermansen, K.; Pfeiffer, A.; Thanopoulou, A.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Schwab, U.; et al. Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes by Lifestyle Changes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, S.; Jena, B.N.; Yeravdekar, R. Emotional and Psychological Needs of People with Diabetes. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 22, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ozairi, A.; Taghadom, E.; Irshad, M.; Al-Ozairi, E. Association Between Depression, Diabetes Self-Care Activity and Glycemic Control in an Arab Population with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2023, 16, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Liu, M.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Q.; Suo, L.; Chen, Y. The Increased Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety in T2DM Patients Associated with Blood Glucose Fluctuation and Sleep Quality. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2022, 22, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayeed, K.A.; Qayyum, A.; Jamshed, F.; Gill, U.; Usama, S.M.; Asghar, K.; Tahir, A. Impact of Diabetes-Related Self-Management on Glycemic Control in Type II Diabetes Mellitus. Cureus 2020, 12, e7845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucock, M.; Gillard, S.; Adams, K.; Simons, L.; White, R.; Edwards, C. Self-Care in Mental Health Services: A Narrative Review. Health Soc. Care Community 2011, 19, 602–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raynor, P.; Pope, C. The Role of Self-Care for Parents in Recovery from Substance Use Disorders. J. Addict. Nurs. 2016, 27, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Indicator | Outcome Measure | Outcome Trend | SOC Trend | Leading Reference First Author Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomarkers and Laboratory Parameters | atherogenic lipoprotein burden | LDL-C | lower | stronger | Olesen 2017 [117] |

| long-term glycaemic control | HbA1c | lower | stronger | Guevara 2018 [31] | |

| short-term glycaemic control | FPG | higher | weaker | Ramos-Valle 2023 [122] | |

| Disease and Progression Risk | risk of insulin resistance | HOMA-IR | higher | weaker | Agardh 2003 [123] |

| risk of T2DM | newly diagnosed T2DM | higher | weaker | Madhu 2019 [124] | |

| risk of T2DM-related complications | incidence of T2DM-related complications | higher | weaker | Ahola 2010 [116] | |

| Lifestyle Behaviours | nutritional status | BMI | lower | higher | Nuccitelli 2018 [125] |

| lifestyle pattern | diet and exercise | higher | stronger | Nilsen 2015 [126] | |

| Patient-reported Outcomes (PROs) | adherence to self-care | level of adherence to self-care | higher | stronger | Vega-Martínez 2025 [127] |

| adherence to therapy | level of adherence to therapy | higher | stronger | Kordbagheri 2024 [128] | |

| distress | level of stress | lower | stronger | He 2006 [129] | |

| fear of hypoglycaemia | level of fear of hypoglycaemia | lower | stronger | Shiu 2004 [130] | |

| quality of life | level of quality of life | higher | stronger | Knight 2012 [131] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mijač, S.; Vitale, K.; Lončarek, K.; Slivšek, G. How the Salutogenic Pattern of Health Reflects in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Narrative Review. Diabetology 2025, 6, 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6110124

Mijač S, Vitale K, Lončarek K, Slivšek G. How the Salutogenic Pattern of Health Reflects in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Narrative Review. Diabetology. 2025; 6(11):124. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6110124

Chicago/Turabian StyleMijač, Sandra, Ksenija Vitale, Karmen Lončarek, and Goran Slivšek. 2025. "How the Salutogenic Pattern of Health Reflects in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Narrative Review" Diabetology 6, no. 11: 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6110124

APA StyleMijač, S., Vitale, K., Lončarek, K., & Slivšek, G. (2025). How the Salutogenic Pattern of Health Reflects in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Narrative Review. Diabetology, 6(11), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6110124