Molecular Structure-Sensitive Detection in MALDI-MS Utilizing Ag, CdTe, and Water-Splitting Photocatalyst

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

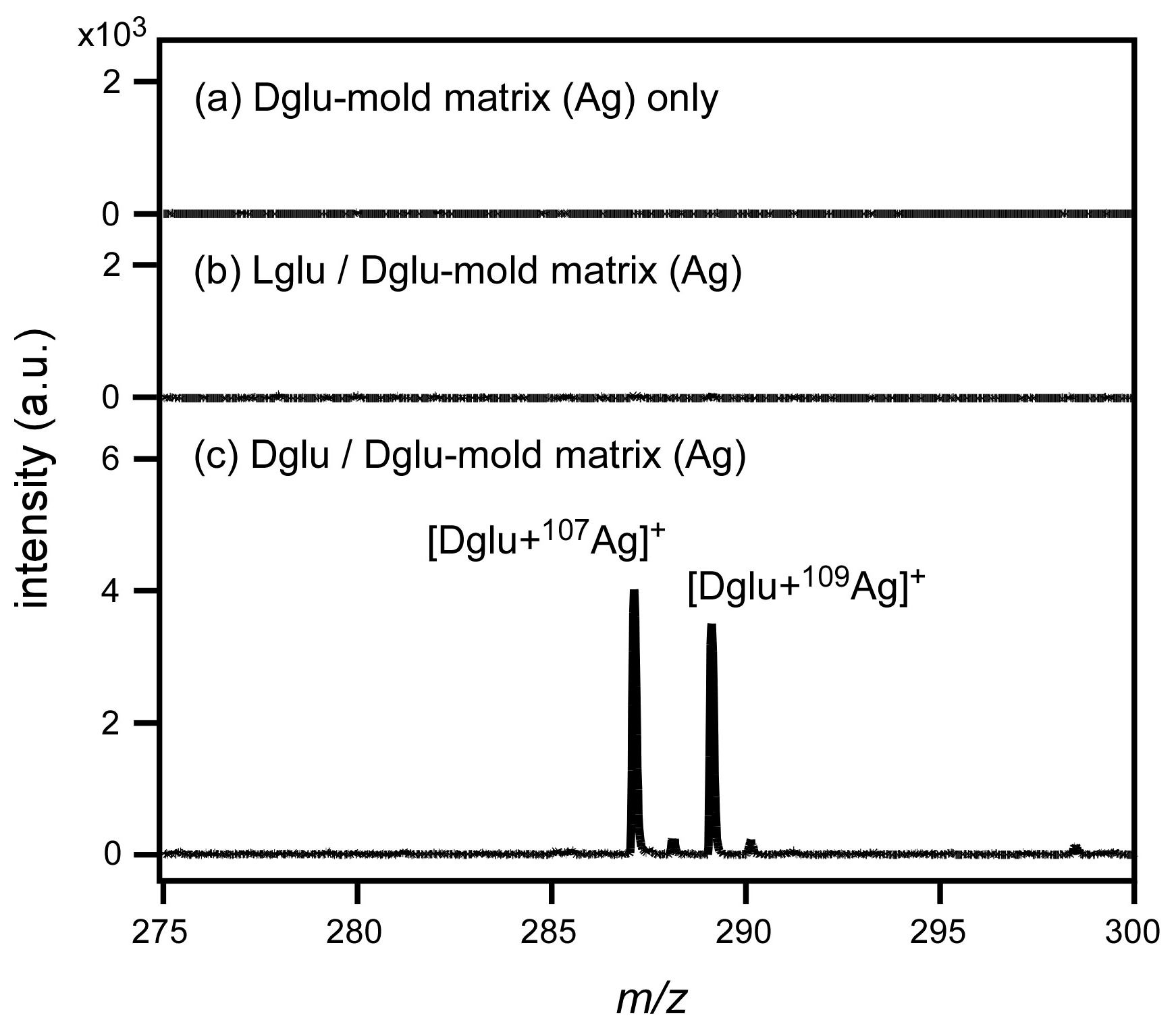

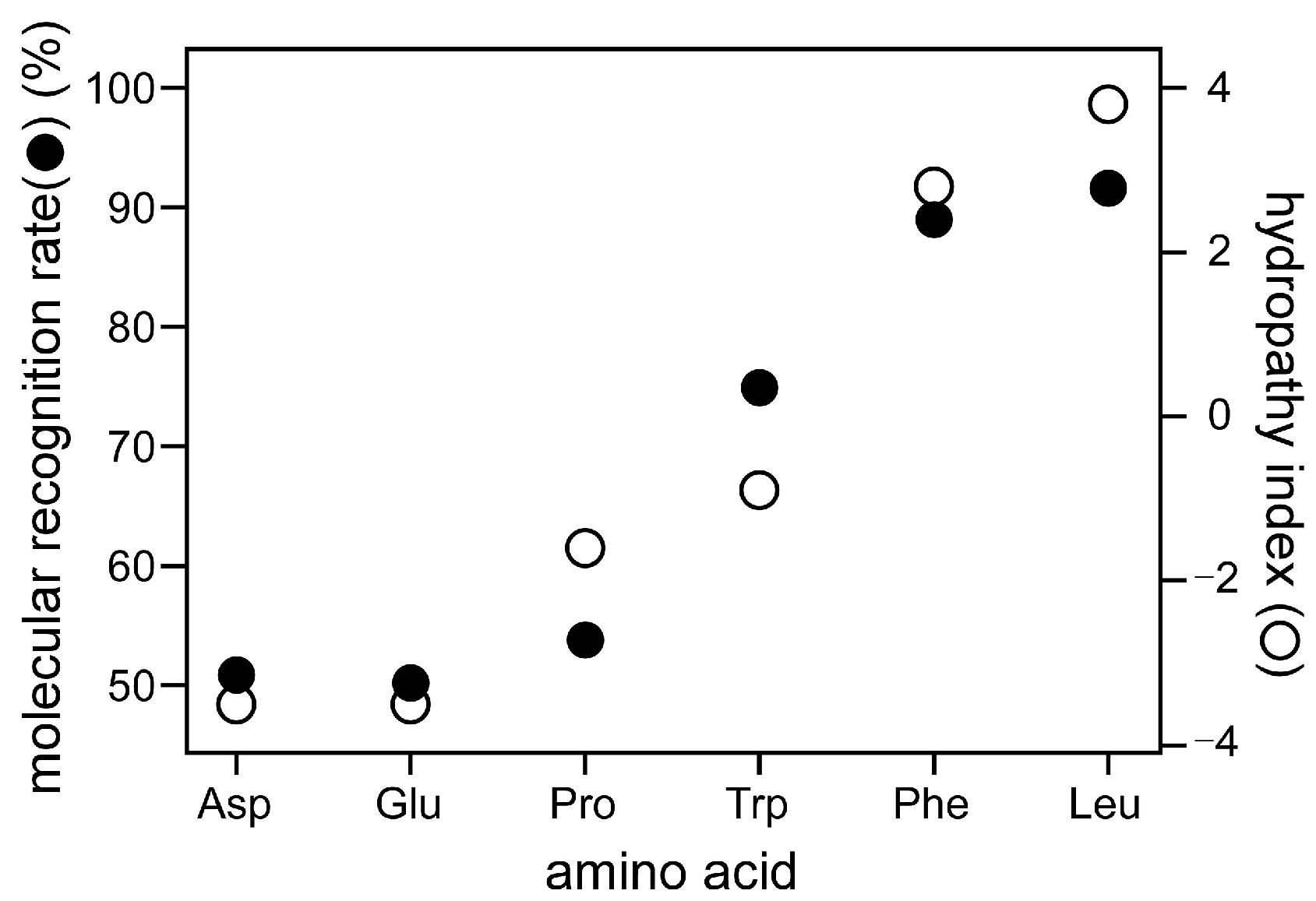

3.1. Mold Matrix by Ag Core

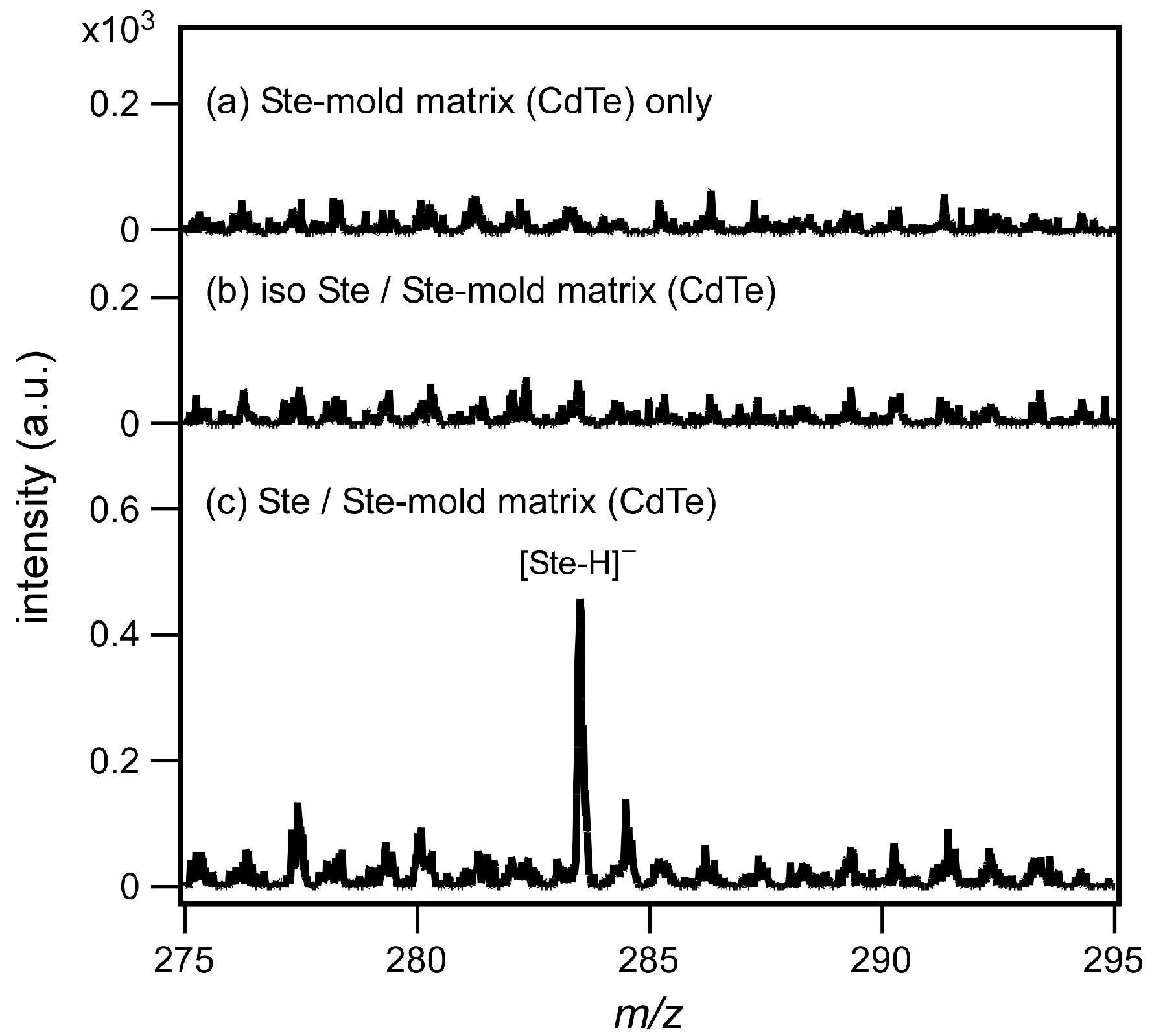

3.2. Mold Matrix by CdTe Core

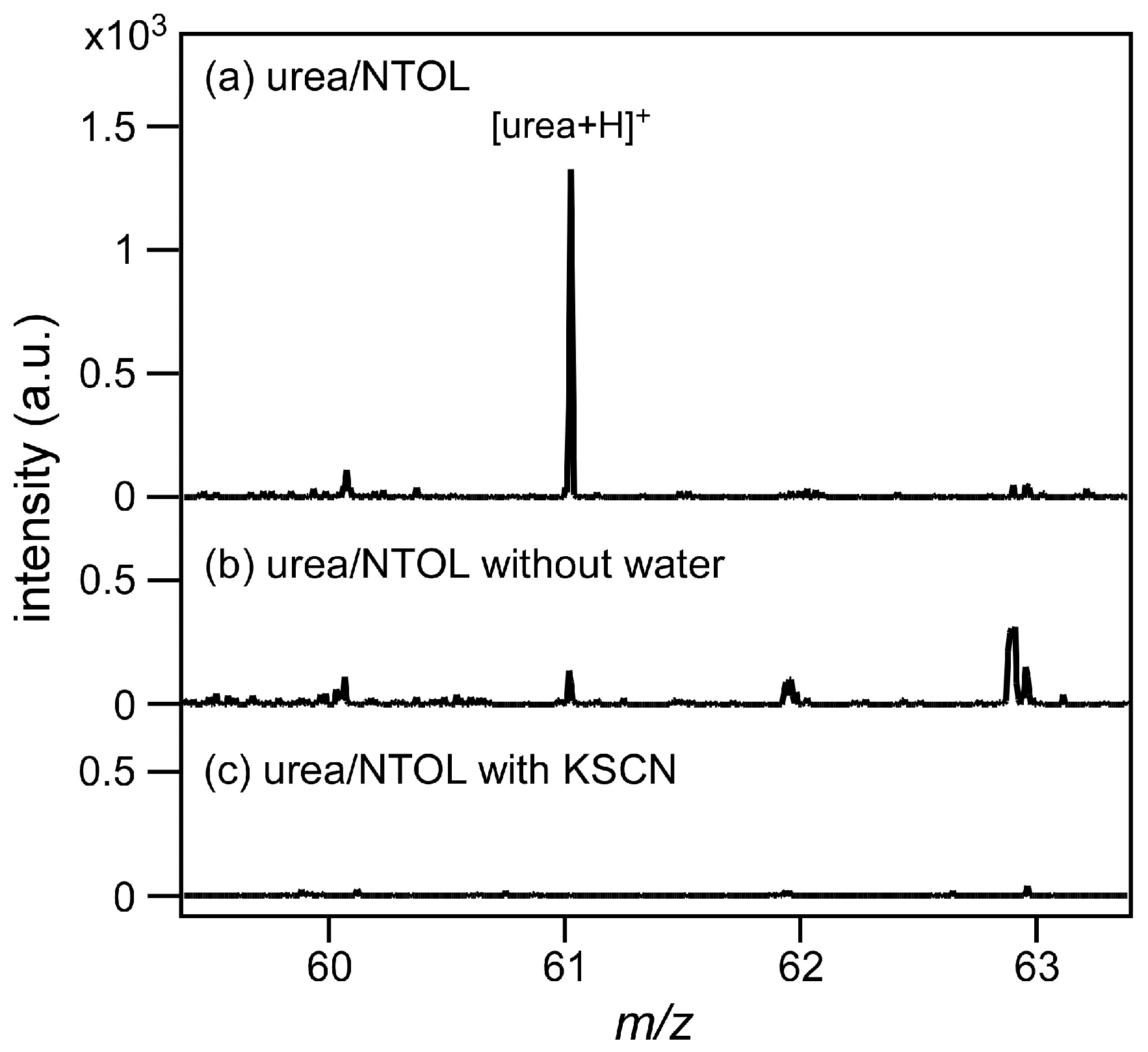

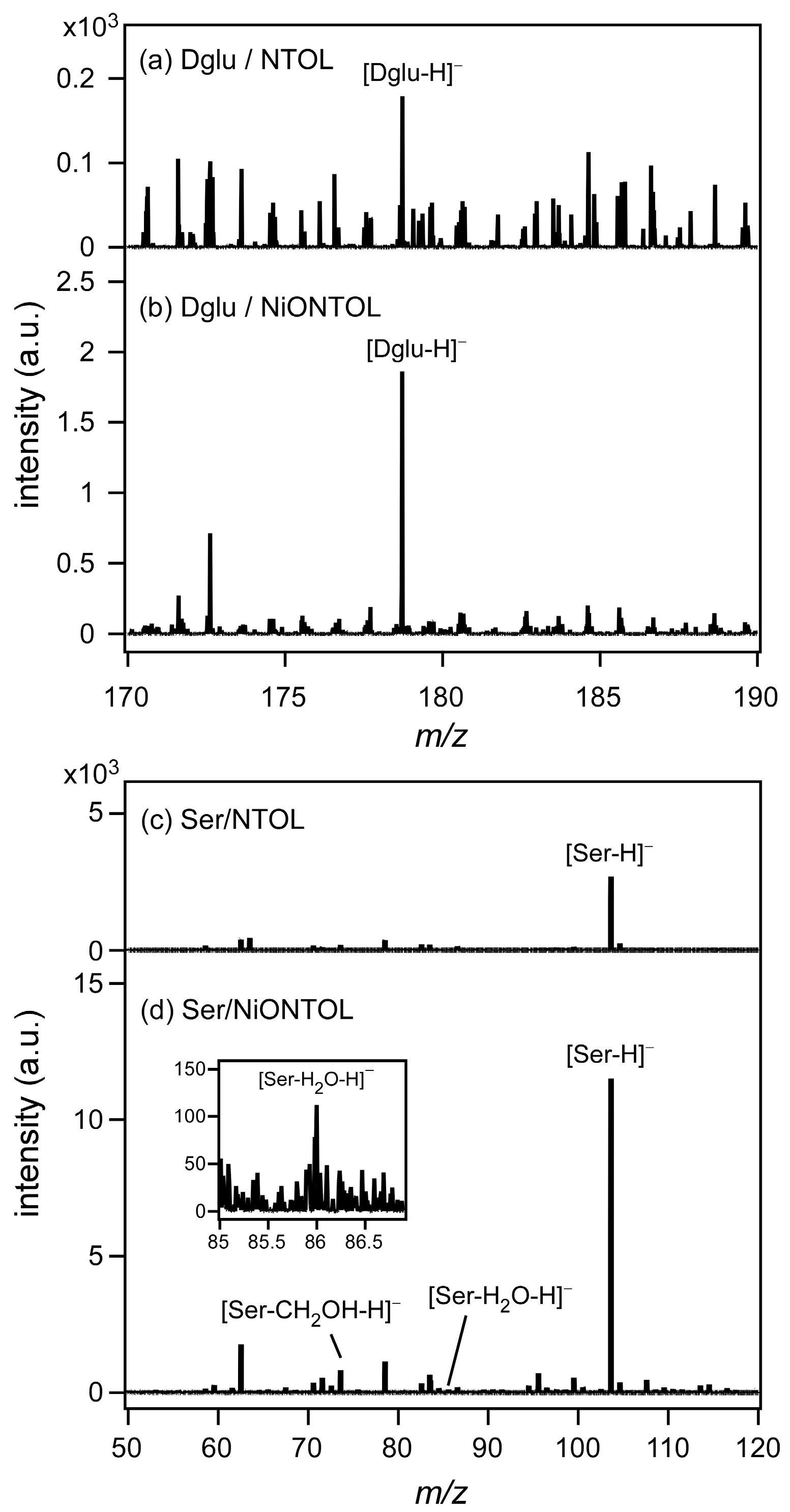

3.3. Water-Splitting Photocatalyst and Application to a Mold Matrix

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MALDI | Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization |

| NTOL | NaTaO3:La(2%) |

| NiONTOL | NiO:NaTaO3:La(2%) |

| Ste | Stearic acid |

| PVME | Polyvinyl methyl ether |

| Dglu | D-glucose |

| CHCA | α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid |

References

- Smith, R.L.; Mitchell, S.C. Thalidomide-type teratogenicity: Structure–activity relationships for congeners. Toxicol. Res. 2018, 7, 1036–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hensley, D.; Cody, J.T. Simultaneous Determination of Amphetamine, Methamphetamine, Methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), and Methylenedioxyethylamphetamine (MDEA) Enantiomers by GC-MS. J. Anal. Toxicol. 1999, 23, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidong, W.; Ring, P.R.; Midtlien, C.; Jiang, X. Development and validation of a sensitive and robust LC–tandem MS method for the analysis of warfarin enantiomers in human plasma. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2001, 25, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Cyronak, M.; Yang, E. Does a stable isotopically labeled internal standard always correct analyte response?: A matrix effect study on a LC/MS/MS method for the determination of carvedilol enantiomers in human plasma. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2007, 43, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Rong, X.; Bu, J.; Liu, Q.; Ouyang, Z. Differentiating enantiomers by directional rotation of ions in a mass spectrometer. Science 2024, 383, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillenkamp, F.; Karas, M. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation, an experience. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2000, 200, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillenkamp, F.; Karas, M.; Beavis, R.C.; Chait, B.T. Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry of Biopolymers. Anal. Chem. 1991, 63, 1193A–1203A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Waki, H.; Ido, Y.; Akita, S.; Yoshida, Y.; Yoshida, T. Protein and polymer analyses up to m/z 100000 by laser ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 1988, 2, 151–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.N.; Ugarov, M.; Egan, T.; Post, J.D.; Langlais, D.; Schultz, J.A.; Woods, A.S. MALDI-ion mobility-TOFMS imaging of lipids in rat brain tissue. J. Mass Spectrom. 2007, 42, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koomen, J.M.; Ruotolo, B.T.; Gillig, K.J.; McLean, J.A.; Russell, D.H.; Kang, M.; Dunbar, K.R.; Fuhrer, K.; Gonin, M.; Schultz, A.J. Oligonucleotide analysis with MALDI–ion-mobility–TOFMS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2002, 373, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, E.; Gillig, K.J.; Ruotolo, B.; Fuhrer, K.; Gonin, M.; Schultz, A.; Russell, D.H. Surface-Induced Dissociation on a MALDI-Ion Mobility-Orthogonal Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometer: Sequencing Peptides from an “In-Solution” Protein Digest. Anal. Chem. 2001, 73, 2233–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So, M.P.; Wan, T.S.M.; Chan, T.-W.D. Differentiation of enantiomers using matrixassisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2000, 14, 692–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Xu, J.; Fujino, T. Chirality and structure-selective MALDI using mold matrix. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, Y. IR Spectroscopic Study on the Hydration and the Phase Transition of Poly(vinyl methyl ether) in Water. Langmuir 2001, 17, 1737–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, Y.; Higuchi, T.; Ikeda, I. Change in Hydration State during the Coil−Globule Transition of Aqueous Solutions of Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) as Evidenced by FTIR Spectroscopy. Langmuir 2000, 16, 7503–7509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H.; Asakura, K.; Kudo, A. Highly Efficient Water Splitting into H2 and O2 over Lanthanum-Doped NaTaO3 Photocatalysts with High Crystallinity and Surface Nanostructure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 3082–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyte, J.; Doolittle, R.F. A Simple Method for Displaying the Hydropathic Character of a Protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1982, 157, 105–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Fujino, T. Quantitative analysis of free fatty acids in human serum using biexciton Auger recombination in cadmium telluride nanoparticles loaded on zeolite. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 9563–9569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, D.; Fairbanks, A.J. Selective anomeric acetylation of unprotected sugars in water. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 1896–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebihara, K. Kagaku Binran, 3rd ed.; Maruzen: Tokyo, Japan, 1984. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, J.; Fujino, T. Molecular Structure-Sensitive Detection in MALDI-MS Utilizing Ag, CdTe, and Water-Splitting Photocatalyst. Analytica 2025, 6, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/analytica6040053

Xu J, Fujino T. Molecular Structure-Sensitive Detection in MALDI-MS Utilizing Ag, CdTe, and Water-Splitting Photocatalyst. Analytica. 2025; 6(4):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/analytica6040053

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Jiawei, and Tatsuya Fujino. 2025. "Molecular Structure-Sensitive Detection in MALDI-MS Utilizing Ag, CdTe, and Water-Splitting Photocatalyst" Analytica 6, no. 4: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/analytica6040053

APA StyleXu, J., & Fujino, T. (2025). Molecular Structure-Sensitive Detection in MALDI-MS Utilizing Ag, CdTe, and Water-Splitting Photocatalyst. Analytica, 6(4), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/analytica6040053