Differences in Quality of Life Related to Lower Urinary Tract, Bowel and Sexual Function After Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy in Patients with and Without Nerve-Sparing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Study Population

2.2. Outcomes

2.2.1. Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC)

2.2.2. International Index of Erectile Function-6 (IIEF-6)

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

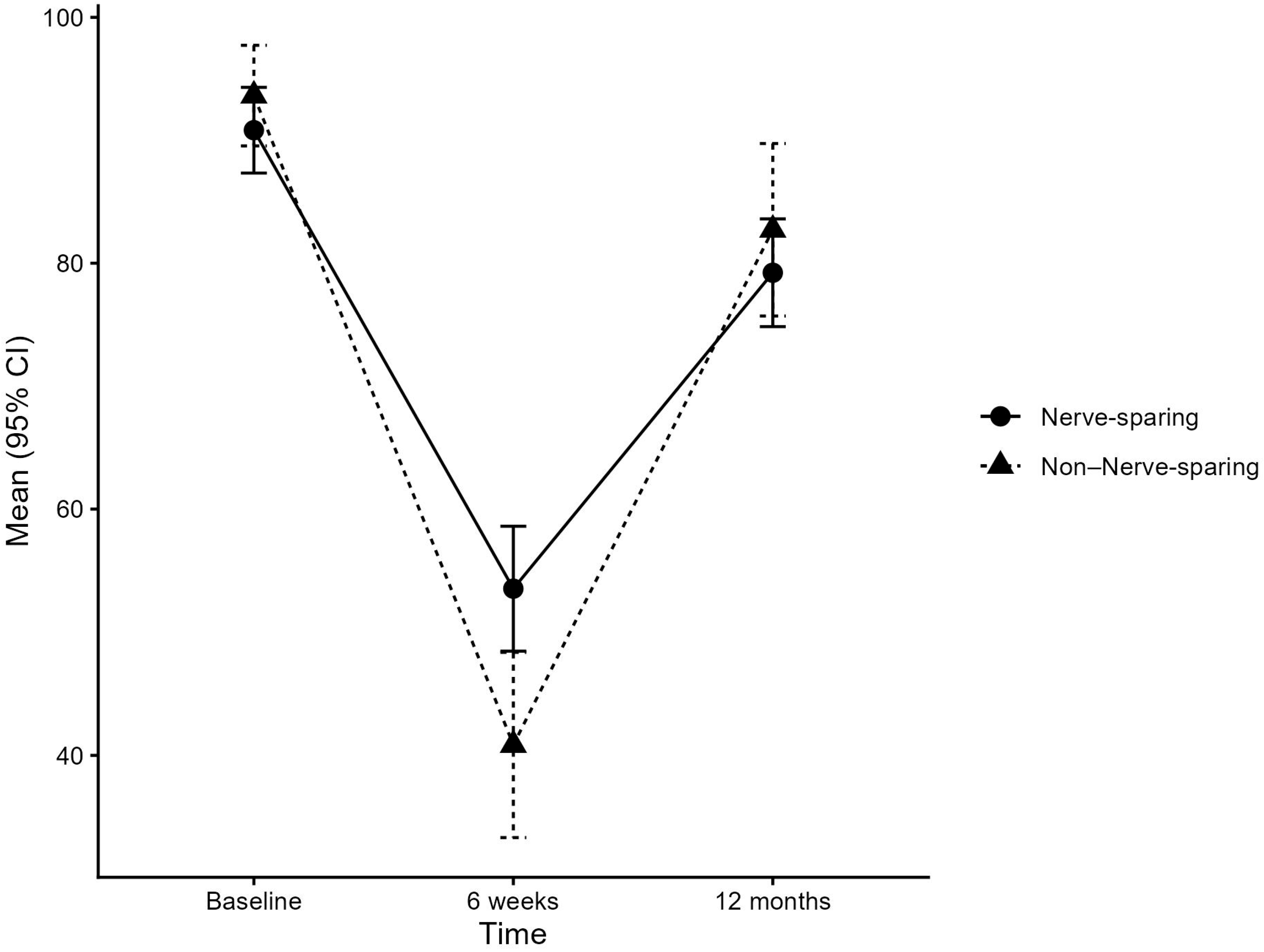

3.1. EPIC Lower Urinary Tract Domain: Function

3.2. EPIC Lower Urinary Tract Domain: Bother

3.3. EPIC Bowel Domain

3.4. Sexual Function Domain

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Results in Context

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EPIC | Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite |

| HRQOL | Health-Related Quality of Life |

| IIEF-6 | International Index of Erectile Function-6 |

| LUT | Lower Urinary Tract |

| MCID | Minimal Clinically Important Difference |

| mpMRI | Multiparametric Prostate Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NNS | Non-Nerve-Sparing |

| NS | Nerve-Sparing |

| PCa | Prostate Cancer |

| PSA | Prostate-Specific Antigen |

| RARP | Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy |

| TUR-P | Transurethral Prostate Surgery |

References

- Union for International Cancer Control (UICC). The Global Cancer Observatory—Globocan 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.uicc.org/news/globocan-2020-global-cancer-data (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- EAU Guidelines. Edn. Presented at the Eau Annual Congress Paris 2024; EAU Guidelines Office: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2024. Available online: https://uroweb.org/guidelines (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Hamdy, F.C.; Donovan, J.L.; Lane, J.A.; Mason, M.; Metcalfe, C.; Holding, P.; Davis, M.; Peters, T.J.; Turner, E.L.; Martin, R.M.; et al. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilt, T.J.; Jones, K.M.; Barry, M.J.; Andriole, G.L.; Culkin, D.; Wheeler, T.; Aronson, W.J.; Brawer, M.K. Follow-up of prostatectomy versus observation for early prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trama, A.; Foschi, R.; Larrañaga, N.; Sant, M.; Fuentes-Raspall, R.; Serraino, D.; Tavilla, A.; Van Eycken, L.; Nicolai, N.; EUROCARE-5 Working Group; et al. Survival of male genital cancers (prostate, testis and penis) in Europe 1999–2007: Results from the eurocare-5 study. Eur. J. Cancer 2015, 51, 2206–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.W.; Drumm, M.R.; Efstathiou, J.A.; Paly, J.J.; Niemierko, A.; Ancukiewicz, M.; Talcott, J.A.; Clark, J.A.; Zietman, A.L. Long-term quality of life after definitive treatment for prostate cancer: Patient-reported outcomes in the second posttreatment decade. Cancer Med. 2017, 6, 1827–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, S.; Koch-Gallenkamp, L.; Bertram, H.; Eberle, A.; Holleczek, B.; Pritzkuleit, R.; Waldeyer-Sauerland, M.; Waldmann, A.; Zeissig, S.R.; Rohrmann, S.; et al. Health-related quality of life in long-term survivors with localised prostate cancer by therapy-results from a population-based study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, E13076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, J.L.; Hamdy, F.C.; Lane, J.A.; Mason, M.; Metcalfe, C.; Walsh, E.; Blazeby, J.M.; Peters, T.J.; Holding, P.; Bonnington, S.; et al. Patient-reported outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1425–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gore, J.L.; Kwan, L.; Lee, S.P.; Reiter, R.E.; Litwin, M.S. Survivorship beyond convalescence: 48-month quality-of-life outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009, 101, 888–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanda, M.G.; Dunn, R.L.; Michalski, J.; Sandler, H.M.; Northouse, L.; Hembroff, L.; Lin, X.; Greenfield, T.K.; Litwin, M.S.; Saigal, C.S.; et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1250–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, P.C.; Lepor, H.; Eggleston, J.C. Radical prostatectomy with preservation of sexual function: Anatomical and pathological considerations. Prostate 1983, 4, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avulova, S.; Zhao, Z.; Lee, D.; Huang, L.-C.; Koyama, T.; Hoffman, K.E.; Conwill, R.M.; Wu, X.C.; Chen, V.; Cooperberg, M.R.; et al. The effect of nerve sparing status on sexual and urinary function: 3-year results from the ceasar study. J. Urol. 2018, 199, 1202–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefermehl, L.; Bossert, K.; Ramakrishnan, V.M.; Seifert, B.; Lehmann, K. A prospective analysis of the effects of nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy on urinary continence based on expanded prostate cancer index composite and international index of erectile function scoring systems. Int. Neurourol. J. 2018, 22, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.H.; Kwon, O.S.; Hong, S.-H.; Kim, S.W.; Hwang, T.-K.; Lee, J.Y. Effect of nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy on urinary continence in patients with preoperative erectile dysfunction. Int. Neurourol. J. 2016, 20, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzou, D.T.; Dalkin, B.L.; Christopher, B.A.; Cui, H. The failure of a nerve sparing template to improve urinary continence after radical prostatectomy: Attention to study design. Urol. Oncol. 2009, 27, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossert, K.; Ramakrishnan, V.M.; Seifert, B.; Lehmann, K.; Hefermehl, L.J. Urinary incontinence-85: An expanded prostate cancer composite (epic) score cutoff value for urinary incontinence determined using long-term functional data by repeated prospective epic-score self-assessment after radical prostatectomy. Int. Neurourol. J. 2017, 21, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.T.; Dunn, R.L.; Litwin, M.S.; Sandler, H.M.; Sanda, M.G. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (epic) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology 2000, 56, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.C.; Riley, A.; Wagner, G.; Osterloh, I.H.; Kirkpatrick, J.; Mishra, A. The international index of erectile function (iief): A multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology 1997, 49, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelleri, J.C.; Rosen, R.C.; Smith, M.D.; Mishra, A.; Osterloh, I.H. Diagnostic evaluation of the erectile function domain of the international index of erectile function. Urology 1999, 54, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fode, M.; Frey, A.; Jakobsen, H.; Sønksen, J. Erectile function after radical prostatectomy: Do patients return to baseline? Scand. J. Urol. 2016, 50, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltink, J.; Hauck, E.W.; Phädayanon, M.; Weidner, W.; Beutel, M.E. Validation of the german version of the international index of erectile function (iief) in patients with erectile dysfunction, peyronie’s disease and controls. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2003, 15, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umbehr, M.H.; Bachmann, L.M.; Poyet, C.; Hammerer, P.; Steurer, J.; Puhan, M.A.; Frei, A. The german version of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (epic): Translation, validation and minimal important difference estimation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Lee, J.A.; Heer, E.; Pernar, C.; Colditz, G.A.; Pakpahan, R.; Imm, K.R.; Kim, E.H.; Grubb, R.L., 3rd; Wolin, K.Y.; et al. One-year urinary and sexual outcome trajectories among prostate cancer patients treated by radical prostatectomy: A prospective study. BMC Urol. 2021, 21, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kampen, M.; De Weerdt, W.; Van Poppel, H.; De Ridder, D.; Feys, H.; Baert, L. Effect of pelvic-floor re-education on duration and degree of incontinence after radical prostatectomy: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2000, 355, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, S.; Doege, D.; Koch-Gallenkamp, L.; Thong, M.S.Y.; Bertram, H.; Eberle, A.; Holleczek, B.; Pritzkuleit, R.; Waldeyer-Sauerland, M.; Waldmann, A.; et al. Age-specific health-related quality of life in disease-free long-term prostate cancer survivors versus male population controls-results from a population-based study. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 2875–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bignante, G.; Orsini, A.; Lasorsa, F.; Lambertini, L.; Pacini, M.; Amparore, D.; Pandolfo, S.D.; Del Giudice, F.; Zaytoun, O.; Buscarini, M.; et al. Robotic-assisted surgery for the treatment of urologic cancers: Recent advances. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2024, 21, 1165–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, F.; Preece, P.; Kapoor, J.; Everaerts, W.; Murphy, D.G.; Corcoran, N.M.; Costello, A.J. Preservation of the neurovascular bundles is associated with improved time to continence after radical prostatectomy but not long-term continence rates: Results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. 2015, 68, 692–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centemero, A.; Rigatti, L.; Giraudo, D.; Lazzeri, M.; Lughezzani, G.; Zugna, D.; Montorsi, F.; Rigatti, P.; Guazzoni, G. Preoperative pelvic floor muscle exercise for early continence after radical prostatectomy: A randomised controlled study. Eur. Urol. 2010, 57, 1039–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.J.; Pisters, L.L.; Davis, J.; Lee, A.K.; Bassett, R.; Kuban, D.A. An assessment of quality of life following radical prostatectomy, high dose external beam radiation therapy and brachytherapy iodine implantation as monotherapies for localized prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2007, 177, 2151–2156; discussion 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnick, M.J.; Koyama, T.; Fan, K.-H.; Albertsen, P.C.; Goodman, M.; Hamilton, A.S.; Hoffman, R.M.; Potosky, A.L.; Stanford, J.L.; Stroup, A.M.; et al. Long-term functional outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, R.; Honda, M.; Teraoka, S.; Shimizu, R.; Kimura, Y.; Iwamoto, H.; Morizane, S.; Hikita, K.; Takenaka, A. Effects of nerve-sparing procedures on bowel function after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: A longitudinal study. Int. J. Med. Robot. 2020, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasorsa, F.; Biasatti, A.; Orsini, A.; Bignante, G.; Farah, G.M.; Pandolfo, S.D.; Lambertini, L.; Reddy, D.; Damiano, R.; Ditonno, P.; et al. Focal therapy for prostate cancer: Recent advances and insights. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.C.; Allen, K.R.; Ni, X.; Araujo, A.B. Minimal clinically important differences in the erectile function domain of the international index of erectile function scale. Eur. Urol. 2011, 60, 1010–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Non- Nerve-Sparing RARP n = 36 | Nerve-Sparing RARP n = 84 | Total n = 120 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) ¶ | 66.1 (6.5) | 63.7 (6.0) | 64.4 (6.2) | 0.066 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) ¶ | 26.4 (3.8) | 26.3 (4.0) | 26.3 (3.9) | 0.9 |

| Smoking status, n (%) § | 0.5 | |||

| Smoker | 5 (14%) | 8 (10%) | 13 (11%) | |

| Non-Smoker | 31 (86%) | 76 (90%) | 107 (89%) | |

| TUR-P, n (%) § | 1.0 | |||

| No | 34 (94%) | 80 (95%) | 114 (95%) | |

| Yes | 2 (6%) | 4 (5%) | 6 (5.0%) | |

| History of abdominal surgery, n (%) † | 1.0 | |||

| No | 25 (69%) | 59 (70%) | 84 (70%) | |

| Yes | 11 (31%) | 25 (30%) | 36 (30%) | |

| Preoperative PSA level (ng/mL), mean (SD) ¶ | 13.4 (8.4) | 7.6 (4.0) | 9.3 (6.3) | <0.001 |

| Clinical tumor stage (2002 TNM), n (%) § | <0.001 | |||

| cT1 | 4 (11%) | 51 (61%) | 55 (46%) | |

| cT2 | 30 (83%) | 32 (38%) | 62 (52%) | |

| cT3 | 2 (6%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (3%) | |

| Pathological tumor stage (2002 TNM), n (%) § | 0.017 | |||

| pT1 | 1 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | |

| pT2 | 23 (64%) | 72 (86%) | 95 (79%) | |

| pT3 | 12 (33%) | 11 (13%) | 23 (19%) | |

| Pathological Gleason-score, n (%) § | <0.001 | |||

| ≤3 + 3 | 7 (19%) | 32 (38%) | 39 (33%) | |

| 3 + 4 | 12 (33%) | 13 (15%) | 25 (21%) | |

| 4 + 3 | 9 (25%) | 38 (45%) | 47 (39%) | |

| ≥4 + 4 | 8 (22%) | 1 (1%) | 9 (8%) | |

| Positive surgical margins, n (%) † | 0.9 | |||

| No | 26 (72%) | 58 (69%) | 84 (70%) | |

| Yes | 10 (28%) | 26 (31%) | 36 (30%) | |

| Lymph node status, n (%) § | 1.0 | |||

| pN0 | 35 (97%) | 80 (95%) | 115 (96%) | |

| pN1 | 1 (3%) | 4 (5%) | 5 (4%) |

| Outcome | Non-Nerve-Sparing Mean (SD) | Nerve-Sparing Mean (SD) | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Difference: NS—NNS (95% CI) | p Value | Mean Difference: NS—NNS (95% CI) | p Value | |||

| LUT function | ||||||

| Baseline | 93.63 (12.09) | 90.82 (16.06) | ||||

| 6 weeks | −52.21 (25.53) | −36.98 (27.83) | 15.23 (4.09, 26.38) | 0.0078 | 17.42 (3.53, 31.31) | 0.0145 |

| 12 months | −11.23 (18.88) | −11.85 (23.18) | −0.63 (−10.40, 9.15) | 0.9 | 0.02 (−12.21, 12.26) | >0.9 |

| LUT bother | ||||||

| Baseline | 83.61 (18.45) | 83.36 (17.48) | ||||

| 6 weeks | −29.74 (30.94) | −21.61 (26.94) | 8.13 (−3.41, 19.67) | 0.17 | 10.97 (−3.22, 25.17) | 0.13 |

| 12 months | +1.83 (16.51) | +2.36 (22.58) | 0.54 (−8.79, 9.87) | 0.91 | −1.76 (−13.33, 9.81) | 0.8 |

| Bowel function | ||||||

| Baseline | 93.03 (10.13) | 94.11 (8.73) | ||||

| 6 weeks | −6.08 (15.90) | −4.66 (13.98) | 1.42 (−4.54, 7.39) | 0.6 | 7.08 (−0.08, 14.24) | 0.053 |

| 12 months | +3.99 (10.52) | +0.76 (12.27) | −3.23 (−8.46, 2.00) | 0.22 | −1.27 (−7.76, 5.21) | 0.7 |

| Bowel bother | ||||||

| Baseline | 93.06 (11.92) | 94.73 (12.01) | ||||

| 6 weeks | −5.63 (19.95) | −3.62 (15.06) | 2.02 (−4.80, 8.83) | 0.6 | 7.25 (−1.18, 15.68) | 0.09 |

| 12 months | +2.78 (13.10) | −0.55 (13.93) | −3.33 (−9.40, 2.74) | 0.3 | −3.68 (−11.22, 3.85) | 0.33 |

| IIEF-6 | ||||||

| Baseline | 15.86 (11.73) | 18.54 (11.44) | ||||

| 6 weeks | −13.27 (12.76) | −12.55 (13.41) | 0.72 (−4.70, 6.15) | 0.8 | 1.50 (−4.88, 7.88) | 0.6 |

| 12 months | −5.55 (14.82) | −11.60 (14.66) | −6.05 (−13.51, 1.41) | 0.11 | −8.44 (−16.82, −0.05) | 0.049 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Merentitis, D.; Neuenschwander, J.; Foerster, B.; John, H.; Bachmann, L.M.; Bodmer, N.S.; Tornic, J. Differences in Quality of Life Related to Lower Urinary Tract, Bowel and Sexual Function After Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy in Patients with and Without Nerve-Sparing. Uro 2026, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/uro6010003

Merentitis D, Neuenschwander J, Foerster B, John H, Bachmann LM, Bodmer NS, Tornic J. Differences in Quality of Life Related to Lower Urinary Tract, Bowel and Sexual Function After Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy in Patients with and Without Nerve-Sparing. Uro. 2026; 6(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/uro6010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleMerentitis, Danae, Julia Neuenschwander, Beat Foerster, Hubert John, Lucas M. Bachmann, Nicolas S. Bodmer, and Jure Tornic. 2026. "Differences in Quality of Life Related to Lower Urinary Tract, Bowel and Sexual Function After Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy in Patients with and Without Nerve-Sparing" Uro 6, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/uro6010003

APA StyleMerentitis, D., Neuenschwander, J., Foerster, B., John, H., Bachmann, L. M., Bodmer, N. S., & Tornic, J. (2026). Differences in Quality of Life Related to Lower Urinary Tract, Bowel and Sexual Function After Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy in Patients with and Without Nerve-Sparing. Uro, 6(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/uro6010003