Abstract

Background/Objectives: Buccal mucosa graft (BMG) is increasingly utilized in reconstructive urological surgeries due to its versatility, robust integration, histological characteristics and low morbidity at the donor site. Initially employed in urethral surgery, BMG use has expanded to complex ureteral and penile reconstructive procedures. This narrative review examines BMG applications in various urological surgeries, comparing its outcomes to other graft types, with a focus on surgical techniques and patient outcomes. Methods: A narrative review was conducted using PubMed and Scopus to identify relevant studies published over the last three decades on the use of BMG in urological reconstructive surgery. Articles in English addressing BMG harvesting, applications and functional outcomes were analyzed. Results: BMG has demonstrated high success rates in every field of its application, especially in urethral reconstruction with an 83–91% efficacy rate in intermediate follow-up. Studies have also reported positive outcomes in complex ureteral and penile curvature surgeries, with patient satisfaction rates reaching up to 85%. Conclusions: BMG is an adaptable tissue graft for urological reconstructive surgeries, offering favorable outcomes with minimal morbidity. Although the current results are encouraging, larger prospective studies with standardized protocols are necessary to fully validate its long-term efficacy and optimize treatment approaches for complex urological reconstructions.

1. Introduction

In reconstructive urological surgery there are different cases in which the use of a graft is needed. A graft is a piece of tissue taken from a part of the body or from a synthetic or engineered source and transplanted to a different area to repair or reconstruct. The first challenge in this kind of surgery is a functional/oncological one, depending on why the surgery is performed, and the second is related to morbidity at the explantation site. At the moment, tissue engineering in reconstructive urology is in its early stages but has great potential [1]. However, the use of autologous graft is widely accepted, and different types of grafts have been investigated in the past few decades (fasci lata graft, skin graft, intestinal graft, bladder mucosa graft, penile/preputial skin graft, etc.). Among these, the buccal mucosa graft (BMG) seems to have many characteristics that make it the preferred graft to use [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9] with a high success rate and integration potential. The BMG is in fact flexible, robust, resistant to infection and cost-effective; does not promote inflammatory reaction; does not contract; and has histological properties that make it a perfect choice for a moist environment. Moreover, it is linked to a low rate of explantation site morbidity. The buccal mucosa graft (BMG) is a type of oral mucosa graft (OMG). This also includes the less commonly used lingual mucosa graft (LMG). The BMG in the urology field was created for urethral surgery. Its use was first described in 1890 by Sapezhko [3] for the treatment of idiopathic urethral stenosis. Subsequently, the BMG was used in 1941 by Humby [4] in a child who had already underwent multiple hypospadias surgeries, resulting in a penoscrotal fistula, and then its use was repurposed in 1992 by Burger et al. [5] and Dessanti et al. [6] for complicated urethral surgeries. Nowadays, AUA and EAU guidelines recommend the use of BMG in particular for complex urethral reconstruction [7,8].

The use of BMG is not only related to the reconstruction of the lower urinary tract; in fact in 1999, for the first time, Naude [10] described his experience with six patients with complicated ureteric stricture and segmental ureteric loss treated with a buccal mucosa graft with good functional results. Nowadays, its use for complex ureteral reconstructive surgery is considered a good option, even if a tailored approach is suggested [11].

Another important field in which the BMG appears to play a major role is Peyronie’s disease surgery in which it seems to have the best functional and esthetic outcomes [12]. Here, we aim to give a brief review of the use of buccal mucosa graft in urological and andrological surgery in order to provide the readers with some suggestions for use in everyday clinical practice, on the basis of recent evidence.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Strategy

From 16 September 2024 to 30 January 2025, two independent reviewers (S.B. and T.C. (Tommaso Ceccato)) performed this research on the PubMed database, Cochrane CENTRAL, Scopus and EMBASE. All references cited in relevant articles were also reviewed and analyzed. This narrative review aims to create an overview of the use of buccal mucosa graft in uro-andrology reconstructive surgery, focusing on the technical aspect of graft harvesting, its different uses in various urological fields and its functional outcomes. The keywords used were “buccal mucosa graft AND urology”, “buccal mucosa graft AND urethroplasty”, “buccal mucosa graft AND ureteroplasty”, “buccal mucosa graft AND penile curvature”, “oral mucosa graft AND urethroplasty”, “oral mucosa graft AND ureteroplasty” and “oral mucosa graft AND penile curvature”.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All cross-sectional, case–control, prospective and retrospective studies, RCTs and reviews were included. Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by consulting the supervisors (T.C. (Tommaso Cai) and L.T.). The following filters were used in the present research: clinical trial, humans, English language and adult. The first selection of studies was performed using abstracts and titles. The reviewers conducted a full-text analysis in cases where the abstract evaluation was insufficient to determine whether the study satisfied inclusion or exclusion criteria.

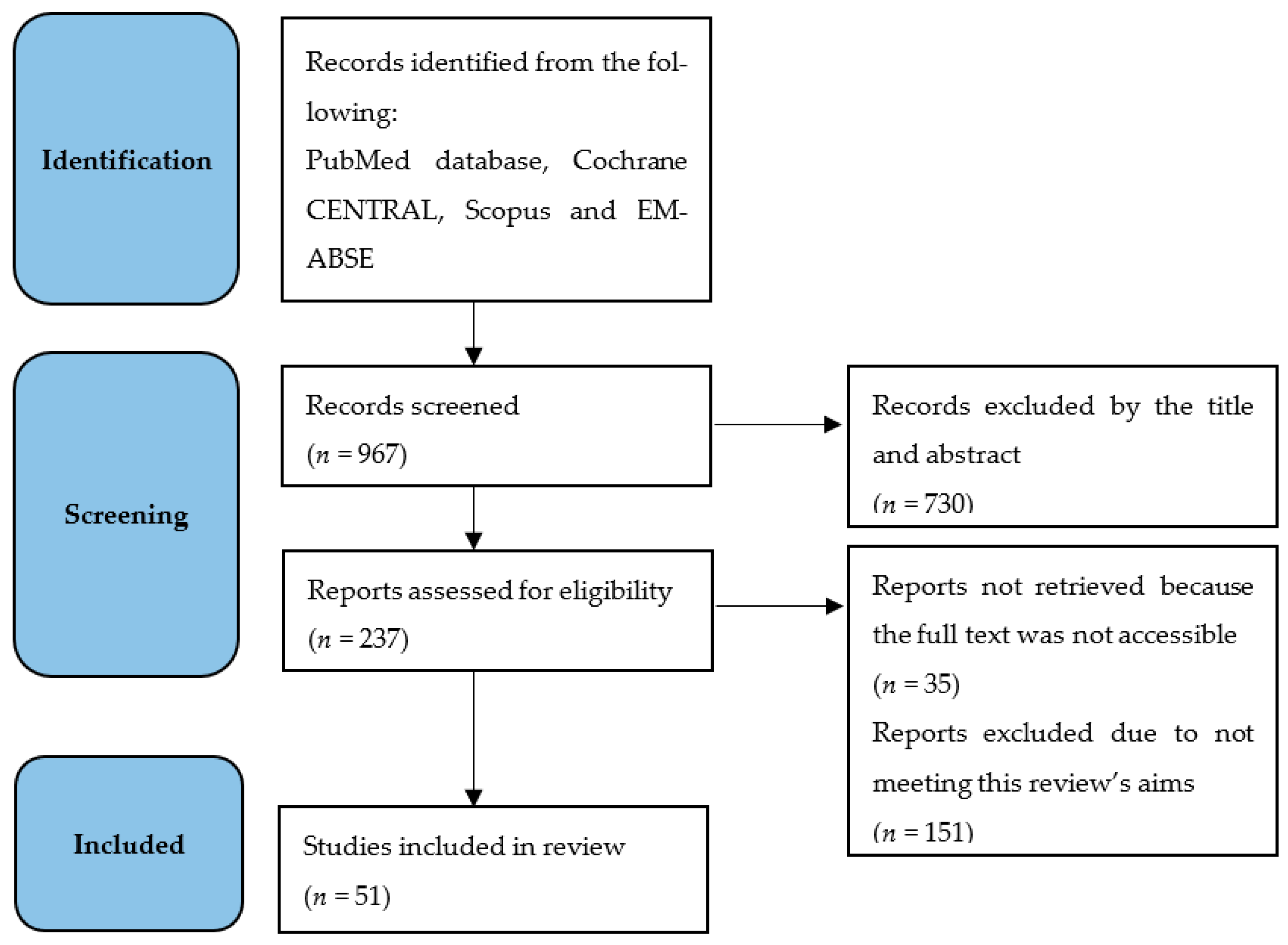

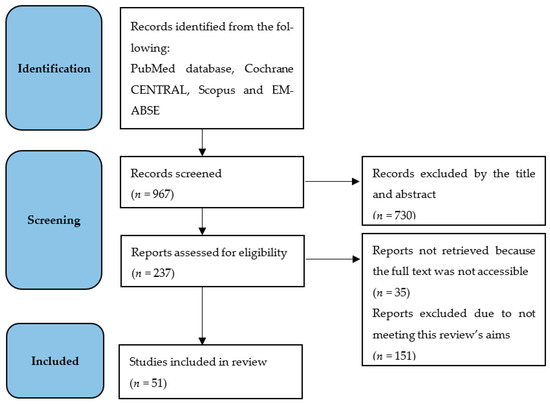

Given the breadth of literature available on the topic as a whole and on each specific active substance, the authors deemed it appropriate to present the findings of this review in a narrative format. A systematic or meta-analytical comparison of such diverse outcomes in terms of measurement, population and methodology falls outside the scope of this work; however, this review was performed in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

This flow chart shows the outcome of the literature search, screening and inclusion in line with the PRISMA statement.

3. Research Evidence

3.1. Buccal Mucosa Graft: The Surgical Procedure

After nasotracheal intubation, the buccal mucosa is exposed, positioning a bite block between the dental arches contralateral to the graft site and retracting the tongue away from the donor site. The anatomical landmarks are then identified. These are represented by the labial commissure and the orifice of the Stensen duct. The mucosal graft limits are drawn with a dermographic pen. It is important to maintain a distance of at least 1 cm from the two anatomical landmarks previously described to avoid complications at the donor site. First, the buccal mucosal area is infiltrated with local anesthesia with a vasoconstrictor. A mucosal and submucosal incision is then performed with a 15-blade scalpel. We proceed with dissection beneath the submucosal plane which must be separated from the underlying buccinator muscle anteriorly and from the retromolar trigone posteriorly. Bipolar cautery at 10 W is used to obtain hemostasis. For small defects, it is usually possible to proceed with primary closure of the donor site by the juxtaposition of the mucosal margins and suture with absorbable 4/0. For larger defects, a second intention healing is preferred. In this case, it could be useful to cover the remaining defect with fat gauze held in place by absorbable stitches. The fat gauze has to be removed after 10 days. An excellent alternative is represented by a sponge sealant patch made by fibrinogen and thrombin, etc., which do not need to be removed. Other types of membranes are described in the literature with interesting results that may represent excellent alternatives in the future for gingival and oral mucosa regeneration [13]. This surgery procedure can be repeated in the same surgical session on the oral mucosa of the opposite site if larger grafts are needed [14]. The patient should be on a soft and cold diet for the first 3–4 days after surgery and then on a soft and warm diet for another 10 days. Chlorhexidine mouthwash rinses should be executed after each meal for two weeks after surgery. It is necessary to encourage the patient, from the first few days after surgery, to perform exercises for mouth opening and mimics to avoid healing with excess fibrosis or lockjaw.

3.2. Buccal Mucosa Graft: Characteristics

Using this technique, a large graft can be obtained from the buccal mucosa of both sides. The extension of the graft should have a maximum diameter of 40–45 mm to avoid lesions of the aforementioned anatomical landmarks. The mucosal graft should be longer than the defect it aims to repair because it has a tendency to contract itself over time [15].

3.3. Buccal Mucosa Graft: Donor Site Complications

Ten days after surgery, the surgical site is generally healed in the case of primary closure, while larger defects are left to heal by secondary intention with a fat gauze as a cover, as previously explained. In this case, complete healing will usually occur within 15–20 days, barring complications. The main complications are pain, swelling, bleeding and infections of the donor site [16]. In particular, about 58% of patients needed analgesia for oral pain, and 24% reported several difficulties to eat and to drink (“impossible/very difficult”) [17]. The lingual mucosa graft showed a higher prevalence of donor site complications in terms of difficulties to eat and drink (resp. 62.1% versus 24.1%; p = 0.004) [17]. Moreover, lingual mucosa graft was associated with more speech impairment (93.1% versus 55.2%) and dysgeusia (48.3% versus 13.8%) as compared to BMG [17]. Other possible complications are lip intrusion if the safety distance from the labial commissure has not been respected, gingival recession if the attached mucosa has been incised and sialocele if the Stensen duct has been interrupted or damaged. An extremely rare complication is oral submucosal fibrosis secondary to graft harvesting [18]. Late complications are reported in a small proportion of patients: problems with drinking (1.7%), eating soft or solid food (3.4%), dysgeusia (5.2%), salivatory changes (10.3%) and speech impairment (15.5%) [17].

3.4. Tips and Tricks

- Not all patients are candidates for oral mucosal harvesting. The selection of patients is the most important part of the flow chart presented above. An accurate medical history must be obtained to eliminate patients who are heavy smokers or have a history of alcohol abuse, a diagnosis of oral lichen planus, etc. An accurate objective examination of the oral cavity must exclude the presence of dental or mucosal pathologies (oral lichen planus, leuko/erythroplakia, dysplasia, carcinomas, etc.) in the harvesting sites. These clinical conditions can lead to the malignant transformation of the oral mucosa [19].

- To reduce the risk of infection of the donor site, it is useful to perform professional oral hygiene treatment a few days before the surgical procedure [20].

- Nasotracheal intubation is recommended to facilitate the harvesting procedure, especially in bilateral sampling.

- It is important to respect and maintain a safe distance from anatomical landmarks: the labial commissure, Stensen duct orifice and attached gingiva.

- The infiltration of the donor site with local anesthesia with a vasoconstrictor allows for the hydro-dissection of the mucosa from the underlying layers, making graft harvesting easier. The vasoconstrictor prevents excessive bleeding, allowing for an easier surgical procedure.

- It is mandatory to identify wide safety margins from the described anatomical landmarks; these can be marked with a dermographic pen, or for example, the Stensen duct can be cannulated with a lacrimal probe.

3.5. Urethroplasty: Techniques and Functional Results

As we mentioned, buccal mucosa grafts have become a widely accepted approach in urethroplasty for reconstructing urethral strictures. This technique is particularly valuable when primary surgical methods have proven unsuccessful or local tissue supply is insufficient or in cases of long-segment (>2 cm) and recurrent strictures [7,8]. Over the years, numerous urethroplasty techniques utilizing buccal mucosa grafts have been developed, highlighting their exceptional versatility—a fundamental attribute given the considerable variability in urethral strictures and their prior treatments. In discussing urethroplasty with BMG, several distinct types of techniques can be identified: dorsal onlay graft, ventral onlay graft, lateral onlay graft, dorsal inlay graft, dorsal inlay and ventral onlay graft. In the dorsal onlay approach, described first by Barbagli et al. in 1996, following the incision of the stricture, a BMG is positioned on the dorsal aspect of the urethra, where it benefits from the robust vascular support provided by the spongiosum tissue [21,22]. In the ventral onlay approach, a BMG is placed on the ventral side of the urethra, offering easier access and a less complicated surgical technique, at the expense of reduced physical and vascular support [23]. The lateral onlay approach was described by Barbagli et al. [24] in cases where ventral urethrotomy carries a risk of significant bleeding, and dorsal urethrotomy may compromise erectile function due to the proximal dissection of the urethra from the corpora cavernosa. On the other hand, in the inlay dorsal approach, a graft is placed on the dorsal side of the urethra within the lumen, rather than on top of the urethra as in the dorsal onlay approach [25,26,27,28]. All the different techniques can be performed at one time or at multiple times. The two-stage technique is specifically employed in cases involving extensive segments of spongiofibrosis, penile strictures, previous hypospadias repair affecting the penile urethra or the presence of insufficient subcutaneous tissue coverage [29]. The second stage of the procedure is usually performed 4–6 months later, to allow the tissues to heal properly. In terms of outcomes, all types of BMG urethroplasty have a similar success rate of 83–91% in the intermediate follow-up, and the two-stage approach seems to be better even if there is a lack of strong evidence [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. Nevertheless, in their meta-analysis considering all types of urethroplasty augmentation, Benson et al. suggested that this rate will decrease in a longer follow-up of 15 years to 45–63% [43]. Recently, BMG urethroplasty has been proven to be as effective as the end-to-end technique, in particular in the treatment of bulbar stricture, with no differences in terms of stricture recurrence and voiding symptoms but with a lower rate of penile complication and erection disfunction [24,30,32,34,44]. In fact, the transecting excision and primary anastomosis (tEPA) appears to have a greater impact on penile length and glans filling precisely due to the interruption of the neurovascular structures [31,32]. Table 1 summarizes all relevant included clinical trials in this subsection of this review.

Table 1.

This table shows a summary of all relevant included clinical trials.

3.6. Ureteroplasty: Techniques and Functional Results

Following the undoubtedly greater experience in urethral surgery, the BMG has also started to be used in the challenging field of ureteral reconstruction [11]. Specifically, it has been used as an option in the management of complex proximal stenosis and in middle ureteric stricture, serving as an alternative to the use of appendiceal flap, ileal replacement or renal auto-transplantation. The choice of BMG surgical technique depends on the considerable variability in stricture characteristics and prior treatments; however, the most commonly performed techniques are ventral onlay ureteroplasty and augmented anastomotic ureteroplasty with a conclusive omental or perinephric fat wrapping [44,45,46]. In a recent meta-analysis comparing OMG ureteroplasty with ileal replacement, You et al. found a similar success rate (94,9% vs. 85.8%) and lower complication rate for OMG surgery, but these data should be interpreted considering the shorter follow-up period and the shorter strictures treated with BMG [44]. Ileal replacement remains, at the moment, the strategy of choice in strictures >8 cm, in bilateral stenosis and in radiated patients. Augmentation ureteroplasty can also be performed with other types of grafts. In 2006, Simonato et al. described for the first time the use of lingual mucosa graft [42], which has a similar success rate to BMG but is associated with more frequent speaking and drinking problems in the postoperative period [37,38,39]. Other commonly used grafts are penile skin and preputial grafts, which seem to have a lower success rate than BMG and come with more complications [40,41]. Other reported grafts are tunica vaginalis, bladder mucosa, colonic mucosa and saphenous vein grafts. There is a very low amount of data on all of these grafts, which limits their routine use. In conclusion, we have to consider that it is challenging to attain definitive results, as most studies are retrospective and exhibit substantial variability in surgical techniques, surgeon experience, stricture characteristics and previous treatment, follow-up protocols and the definitions of outcomes. Ultimately, BMG also seems to be used safely for female urethral stricture, but the data available are limited [47]. Table 2 summarizes all relevant included studies in this subsection of this review.

Table 2.

This table shows a summary of all relevant included meta-analyses and clinical trials.

3.7. Ureteroplasty: Laparoscopic Robotic-Assisted Surgery

One of the mainstays of robotic ureteral restoration is robotic buccal mucosa graft ureteroplasty (RU-BMG). This technique is a flexible and feasible surgical procedure for treating long-segment strictures of the ureteropelvic junction, proximal ureter or mid-ureter when performing a tension-free ureteroureterostomy could be challenging [48]. Patients with significant peri-ureteral scarring and obliteration of normal dissection planes who have had unsuccessful ureteroplasty may also benefit from RU-BMG. The flexibility and feasibility of RU-BMG are due also to the fact that compared to conventional methods, RU-BMG frequently requires a less thorough ureterolysis, which reduces the amount of ureteral vascular disruption during the recovery phase [48]. The first series of RU-BMG was described by Zhao et al. in 2015 [49], demonstrating 100% clinical success in four patients treated with the robotic-assisted reconstruction of the ureter using buccal mucosa graft [49]. Recently, Sahay et al. reported their experience with 16 cases of BMG ureteroplasty, which were performed both laparoscopically and robotically, showing that RU-BMG provides the benefits of improved ergonomics, easy maneuverability and precision surgery to patients [50]. The series of RU-BMG reported by Yang et al. proved the effectiveness of robotic-assisted ureteroplasty with BMG onlay in reconstructing the proximal and middle ureters’ long-segment stricture [51]. Finally, You Y. et al. conducted a meta-analysis and systematic review to compare the functional and clinical results of ileal ureter replacement and RU-BMG [44]. According to their analysis of 23 trials, RU-BMG is a safe, minimally invasive and effective treatment for lengthy ureteric strictures, particularly when ureter segments of less than 8 cm are obstructed [44]. In conclusion, the buccal mucosa graft ureteroplasty performed by using laparoscopic robotic-assisted surgery should be considered the gold standard treatment of long-segment strictures of the ureteropelvic junction, proximal ureter or mid-ureter. Table 3 summarizes all relevant included studies in this subsection of this review.

Table 3.

This table shows a summary of all relevant included meta-analyses and clinical trials in this subsection.

3.8. Penile Curvature Surgery: Techniques and Functional Results

The BMG can also be used in straightening penile surgery in the second/chronic stage of Peyronie’s disease (Induratio Penis Plastica) (IPP), when the fibrotic plaque is stable and asymptomatic for at least six to twelve months [52]. In particular, at this point in the course of the disease, for a patient with penile deformity and severe stable penile curvature, erection disfunction (ED) or penile loss of length, after a comprehensive counseling session examining the advantages and disadvantages, corrective surgery can be proposed to the patient. Over the years, numerous surgical techniques have been developed, including tunica albuginea plication (shortening procedures of the convex part), plaque incision/plaque excision and grafting (lengthening procedures) and the possible contextual insertion of a penile prosthesis in a patient with prior ED [53]. Lengthening procedures are specifically indicated for a penile curvature of more than 60° or when a shortening technique would result in a reduction of more than 20% of the total penile length [54]. In these procedures, after degloving the penis without performing a circumcision unless the foreskin is phimotic [54], the surgeon has to assess the curvature of the penis and isolate the dorsal neurovascular bundle. Subsequently a relaxing incision/partial excision of the plaque on the maximum concave part of the curvature has to be performed. At the moment, no incision procedure has been proven to be surely superior to the other, with the modified H- or double Y-incision being the most commonly used nonetheless, but the complete excision of the plaque is now an abandoned practice due to its increased possibility of DE [55,56,57]. When we consider the use of a graft to fulfill the tunica albuginea defect in IPP surgery, we can choose among an autologous graft (vein, dermis, tunica vaginalis, tunica albuginea, buccal mucosa, lingual mucosa, fascia lata) or non-autologous graft (allograft: human dermis, human pericardium, human fascia lata, human dura mater, human amniotic membrane; xenograft: bovine pericardium, porcine small intestinal submucosa, porcine dermis, equine collagen fleece). Synthetic grafts are no longer an option because of their collateral effect and antigenicity [57,58]. All grafts have pros and cons with none being absolutely superior, and their use has to be tailored to the patient’s will, the disease characteristics and the surgeon’s experience [52,56]. In this kind of surgery, non-autologous grafts are generally more popular because of their lower morbidity and the minor operative time needed, but the few experiences with BMG are promising. In a small series of 32 patients, Zucchi et al. [59] described a high patient satisfaction rate (85%), a low incidence of DE (4%) and a high rate of penile straightening (96%) in patients who underwent BMG IPP surgery. Similar results were reached before by Shioshvili et al. in 2005 [60] and by Cormio et al. in 2009 [61] and have been confirmed by a recent meta-analysis that describes the BMG as the best-performing graft [12]. In a recent small series, the LMG also showed promising results [62]. Table 4 summarizes all relevant included studies in this subsection of this review.

Table 4.

This table shows a summary of all relevant included position statements, reviews and clinical trials.

3.9. Hypospadias Surgery in Adults: The Role of Buccal Mucosa Graft

BMG is, today, recognized as the standard of care in the reconstruction of penoscrotal hypospadias with very good results in terms of functional outcome and patients’ satisfaction [63]. Twelve years is the average age of people who have had hypospadias surgically repaired [63,64]. Even though the number of adults who go untreated has been declining in recent years, the functional outcomes and patient outcomes of surgically correcting hypospadias are excellent. At a mean 28-month follow-up, Zhao et al. showed that buccal mucosa graft as a tube is a reliable and long-lasting method of two-stage repair for severe and complex adult hypospadias, reporting very good results in terms of outcomes [65]. According to Sahin et al., buccal mucosa is a feasible and reliable graft in challenging situations as well, such as adults who have had multiple surgeries or who are circumcised [66].

3.10. Complications and Preventing Strategies for Reducing Complications

Several complications after BMG are described in the literature, particularly in relation to graft rejection and surgical site infections [67]. Surgical site infection is one of the most described complications affecting the functional results. Recently Pogorelić et al. reported the results of a study comparing the safety and efficacy of triclosan-coated PDS Plus sutures versus uncoated PDS II sutures for the prevention of SSIs after hypospadias repair [67]. They demonstrated that the use of PDS Plus in hypospadias surgery significantly reduces the incidence of SSI, postoperative fistulas and reoperation rates compared to PDS II [67]. In this sense, the use of a specific suture should be considered in patients at high risk of surgical site infection. New technologies and materials have been recently developed with the aim of repairing and reconstructing the lost tissue with promising results [68]. However, future studies comparing new technologies and materials with BMG are needed before introducing these new techniques into everyday clinical practice [68].

3.11. The Use of BMG in Pediatric Surgery

BMG is most frequently used in pediatric surgery to treat hypospadias and urethral and ureteral strictures. It is crucial to draw attention to certain elements, even if the surgical techniques are fairly comparable to those used on adults. Recently, Han et al. reported their experience with 15 pediatric and adolescent patients who underwent robot-assisted ureteroplasty with BMG, showing that BMG appears to be safe and feasible for repairing long ureteral strictures in the pediatric setting [69]. The use of robotic surgery for BMG should be considered as the usual practice, just like in the adult setting. Regarding ureteroplasty, there are some aspects to highlight in pediatric surgery. Firstly, concerns exist that the neourethra might not develop in proportion to the phallus [70]. In a cohort of 137 boys who underwent staged BMGU before the age of 12 years, Figueroa et al. demonstrated that buccal mucosa grafts appear to grow proportionally to the phallus after pubertal endogenous androgen stimulation [70]. Regarding the donor site, Elifranji et al. reported their experience with the use of upper lip graft for urethral augmentation in the pediatric setting [71]. They showed that upper lip graft is safe and easy to obtain with a limited complication rate, even if it provides a limited amount of tissue for urethral augmentation; therefore it is not an option for long urethroplasties [71]. Next, regarding hypospadias repair, an interesting issue is the use of BMG in adult patients with a history of hypospadias repair who required subsequent urethroplasty. In 2018, Morrison et al. reported their experience with 32 patients [72]. They showed that very good outcomes can be achieved using a 2-stage approach with the replacement or augmentation of the urethral plate in adults with failed hypospadias repair [72]. Finally, Djordjevic et al. reported a novel and 1-stage technique of using a specially shaped buccal mucosa graft for simultaneous ventral tunica grafting and urethroplasty for severe hypospadias repair [73], showing that this technique is a viable and reliable option for the single-stage repair of scrotal hypospadias with severe chordee [73]. The role of BMG in pediatric surgery increased in recent years, showing excellent functional and clinical outcomes. Table 5 summarizes all relevant included studies in this subsection of this review.

Table 5.

This table shows a summary of all relevant included clinical trials.

4. Novel Applications

Due to its characteristics, BMG has also found experimental applications in other types of reconstructive surgeries, for which data are still extremely limited. One of the most promising fields seems to be its use in the treatment of refractory bladder neck contraction, first described by Avalone et al., whose results were later confirmed by Bozkurt et al. [74,75].

5. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Urological reconstructive surgery is a complex field in which each intervention must consider patient expectations, disease characteristics, graft/flap properties and the surgeon’s expertise to provide a tailored solution for each patient. In this context, the BMG is surely a versatile, efficient and cost-effective tissue that can safely be used in different urological reconstructive surgeries with a high rate of success in terms of functional outcomes. Its promising results have been observed in multiple applications, from urethral surgery to penile curvature surgery passing through ureteral reconstruction, but larger, prospective studies with standardized protocols are necessary to fully validate its long-term efficacy and optimize patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.C. (Tommaso Cai) and L.T.; methodology, M.C. and G.S.; software, S.B. and T.C. (Tommaso Ceccato); data curation, S.B., T.C. (Tommaso Ceccato), M.C. and G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B. and T.C. (Tommaso Cai); writing—review and editing, L.T.; supervision, T.C. (Tommaso Cai) and L.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMG | Buccal mucosa graft |

| OMG | Oral mucosa graft |

| LMG | Lingual mucosa graft |

| tEPA | Transecting excision and primary anastomosis |

| ED | Erection disfunction |

References

- Ławkowska, K.; Rosenbaum, C.; Petrasz, P.; Kluth, L.; Koper, K.; Drewa, T.; Pokrywczynska, M.; Adamowicz, J. Trauma and Reconstructive Urology Working Party of the European Association of Urology Young Academic Urologists. Tissue engineering in reconstructive urology-The current status and critical insights to set future directions-critical review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 10, 1040987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Markiewicz, M.R.; Lukose, M.A.; Margarone, J.E.; Barbagli, G.; Miller, K.S.; Chuang, S.K. The oral mucosa graft: A systematic review. J. Urol. 2007, 178, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korneyev, I.; Ilyin, D.; Schultheiss, D.; Chapple, C. The first oral mucosal graft urethroplasty was carried out in the 19th century: The pioneering experience of Kirill Sapezhko (1857–1928). Eur. Urol. 2012, 62, 624–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humby, G.; Twistington Higgins, T. A one-stage operation for hypospadias. Br. J. Surg. 1941, 29, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürger, R.A.; Müller, S.C.; el-Damanhoury, H.; Tschakaloff, A.; Riedmiller, H.; Hohenfellner, R. The buccal mucosal graft for urethral reconstruction: A preliminary report. J. Urol. 1992, 147, 662–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dessanti, A.; Rigamonti, W.; Merulla, V.; Falchetti, D.; Caccia, G. Autologous buccal mucosa graft for hypospadias repair: An initial report. J. Urol. 1992, 147, 1081–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wessells, H.; Morey, A.; Vanni, A.; Rahimi, L.; Souter, L. Urethral stricture disease guideline amendment. J. Urol. 2023, 210, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association of Urology. EAU Guidelines on Urethral Stricture 2023. Uroweb. Available online: https://uroweb.org/guidelines (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Gn, M.; Sterling, J.; Sinkin, J.; Cancian, M.; Elsamra, S. The Expanding Use of Buccal Mucosal Grafts in Urologic Surgery. Urology 2021, 156, e58–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naude, J.H. Buccal mucosal grafts in the treatment of ureteric lesions. BJU Int. 1999, 83, 751–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, A.N.; Mishra, K.; Zhao, L.C. Buccal Mucosal Ureteroplasty for the Management of Ureteral Strictures: Patient Selection and Considerations. Res. Rep. Urol. 2022, 14, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Natsos, A.; Tatanis, V.; Kontogiannis, S.; Waisbrod, S.; Gkeka, K.; Obaidad, M.; Peteinaris, A.; Pagonis, K.; Papadopoulos, C.; Kallidonis, P.; et al. Grafts in Peyronie’s surgery without the use of prostheses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J. Androl. 2024, 26, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- De Santis, D.; Gelpi, F.; Castellani, R.; Palumbo, C.; Ferretti, M.; Zanotti, G.; Zotti, F.; Montagna, L.; Luciano, U.; Marconcini, S.; et al. Bi-layered collagen nano-structured membrane prototype collagen matrix CM-10826 for oral soft tissue regeneration: An in vivo ultrastructural study on 13 patients. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2019, 33 (Suppl. 1), 29–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, İ.H.; Yalçınkaya, F.; Sertçelik, M.N.; Zengin, K. Comparison of uni-and bilateral buccal mucosa harvesting in terms of oral morbidity. Turk. J. Urol. 2013, 39, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chauhan, S.; Yadav, S.S.; Tomar, V. Outcome of buccal mucosa and lingual mucosa graft urethroplasty in the management of urethral strictures: A comparative study. Urol. Ann. 2016, 8, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Akyüz, M.; Güneş, M.; Koca, O.; Sertkaya, Z.; Kanberoğlu, H.; Karaman, M.İ. Evaluation of intraoral complications of buccal mucosa graft in augmentation urethroplasty. Turk. J. Urol. 2014, 40, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lumen, N.; Vierstraete-Verlinde, S.; Oosterlinck, W.; Hoebeke, P.; Palminteri, E.; Goes, C.; Maes, H.; Spinoit, A.F. Buccal Versus Lingual Mucosa Graft in Anterior Urethroplasty: A Prospective Comparison of Surgical Outcome and Donor Site Morbidity. J. Urol. 2016, 195, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, H.M.; Rao, S.; Sharma, A.; Galhotra, V. Oral Submucous Fibrosis Secondary to Buccal Mucosal Graft for Urethroplasty. Indian. J. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2022, 74 (Suppl 3), 5601–5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zotti, F.; Nocini, R.; Capocasale, G.; Fior, A.; Peretti, M.; Albanese, M. Malignant transformation evidences of Oral Lichen Planus: When the time is of the essence. Oral. Oncol. 2020, 104, 104594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardo, A.; Baccini, F.; De Manzoni, R.; Viviani, M.; Brentaro, S.; Zangani, A.; Faccioni, P.; Luciano, U.; Zuffellato, N.; Signoriello, A.; et al. Air polishing therapy in supportive periodontal treatment: A systematic review. J. Appl. Cosmetol. 2023, 41, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbagli, G.; Palminteri, E.; Rizzo, M. Dorsal onlay graft urethroplasty using penile skin or buccal mucosa in adult bulbourethral strictures. J. Urol. 1998, 160, 1307–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbagli, G.; Selli, C.; Tosto, A.; Palminteri, E. Dorsal free graft urethroplasty. J. Urol. 1996, 155, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner-Warwick, R. The use of buccal mucosa patch grafts in the repair of bulbar urethral strictures. J. Urol. 1977, 118, 671–674. [Google Scholar]

- Barbagli, G.; Palminteri, E.; Guazzoni, G.; Montorsi, F.; Turini, D.; Lazzeri, M. Bulbar urethroplasty using buccal mucosa grafts placed on the ventral, dorsal or lateral surface of the urethra: Are results affected by the surgical technique? J. Urol. 2005, 174, 955–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, X.; Xing, Q.; Ren, S.; Song, Y.; Li, C.; Hao, C.; Wang, J. The urinary and sexual outcomes of buccal mucosal graft urethroplasty versus end-to-end anastomosis: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Sex. Med. 2024, 12, qfae064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gupta, N.P.; Ansari, M.S.; Dogra, P.N.; Tandon, S. Dorsal buccal mucosal graft urethroplasty by a ventral sagittal urethrotomy and minimal-access perineal approach for anterior urethral stricture. BJU Int. 2004, 93, 1287–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asopa, H.S.; Garg, M.; Singhal, G.G.; Singh, L.; Asopa, J.; Nischal, A. Dorsal free graft urethroplasty for urethral stricture by ventral sagittal urethrotomy approach. Urology 2001, 58, 657–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palminteri, E.; Manzoni, G.; Berdondini, E.; Di Fiore, F.; Testa, G.; Poluzzi, M.; Molon, A. Combined dorsal plus ventral double buccal mucosa graft in bulbar urethral reconstruction. Eur. Urol. 2008, 53, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangera, A.; Patterson, J.M.; Chapple, C.R. A systematic review of graft augmentation urethroplasty techniques for the treatment of anterior urethral strictures. Eur. Urol. 2011, 59, 797–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberca-Del Arco, F.; Santos-Pérez, D.L.; Blanca, R.; Amores Vergara, C.; Herrera-Imbroda, B.; Sáez-Barranquero, F. Bulbar urethroplasty techniques and stricture recurrence: Differences between end-to-end urethroplasty versus the use of graft. Minerva Urol. Nephrol. 2024, 76, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsen, O.J.; Holm, H.V.; Ekerhult, T.O.; Lindqvist, K.; Grabowska, B.; Persson, B.; Sairanen, J. To Transect or Not Transect: Results from the Scandinavian Urethroplasty Study, A Multicentre Randomised Study of Bulbar Urethroplasty Comparing Excision and Primary Anastomosis Versus Buccal Mucosal Grafting. Eur. Urol. 2022, 81, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oszczudlowski, M.; Yepes, C.; Dobruch, J.; Martins, F.E. Outcomes of transecting versus non-transecting urethroplasty for bulbar urethral stricture: A meta-analysis. BJU Int. 2023, 132, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Xing, Y.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Q.; Li, C.; Guo, C.; Wang, J.; Hao, C. Low risk of erectile dysfunction after nontransecting bulbar urethroplasty for urethral stricture: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sex. Med. 2023, 21, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K.M.; Blakely, S.A.; O’Donnell, C.I.; Nikolavsky, D.; Flynn, B.J. Primary non-transecting bulbar urethroplasty long-term success rates are similar to transecting urethroplasty. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2017, 49, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapple, C.; Andrich, D.; Atala, A.; Barbagli, G.; Cavalcanti, A.; Kulkarni, S.; Mangera, A.; Nakajima, Y. SIU/ICUD Consultation on Urethral Strictures: The management of anterior urethral stricture disease using substitution urethroplasty. Urology 2014, 83 (Suppl. 3), S31–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasionowska, S.; Bochinski, A.; Shiatis, V.; Singh, S.; Brunckhorst, O.; Rees, R.W.; Ahmed, K. Anterior Urethroplasty for the Management of Urethral Strictures in Males: A Systematic Review. Urology 2022, 159, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barratt, R.; Chan, G.; La Rocca, R.; Dimitropoulos, K.; Martins, F.E.; Campos-Juanatey, F.; Greenwell, T.J.; Waterloos, M.; Riechardt, S.; Osman, N.I.; et al. Free Graft Augmentation Urethroplasty for Bulbar Urethral Strictures: Which Technique Is Best? A Systematic Review. Eur. Urol. 2021, 80, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Chua, M.; Talla, V.; Fernandez, N.; Ming, J.; Sarino, E.M.; DeLong, J.; Virasoro, R.; Tonkin, J.; McCammon, K. Lingual versus buccal mucosal graft for augmentation urethroplasty: A meta-analysis of surgical outcomes and patient-reported donor site morbidity. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2021, 53, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, G.; Sharma, S.; Parmar, K. Buccal mucosa or penile skin for substitution urethroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian. J. Urol. 2020, 36, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lumen, N.; Oosterlinck, W.; Hoebeke, P. Urethral reconstruction using buccal mucosa or penile skin grafts: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Urol. Int. 2012, 89, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horiguchi, A. Substitution urethroplasty using oral mucosa graft for male anterior urethral stricture disease: Current topics and reviews. Int. J. Urol. 2017, 24, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonato, A.; Gregori, A.; Lissiani, A.; Galli, S.; Ottaviani, F.; Rossi, R.; Zappone, A.; Carmignani, G. The tongue as an alternative donor site for graft urethroplasty: A pilot study. J. Urol. 2006, 175, 589–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, C.R.; Li, G.; Brandes, S.B. Long term outcomes of one-stage augmentation anterior urethroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2021, 47, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- You, Y.; Gao, X.; Chai, S.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, Z.; Cheng, G.; Li, B.; et al. Oral mucosal graft ureteroplasty versus ileal ureteric replacement: A meta-analysis. BJU Int. 2023, 132, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, B.; Fan, J.; Cheng, S.; Fan, S.; Yin, L.; Li, Z.; Guan, H.; Yang, K.; Li, X. The application of the “omental wrapping” technique with autologous onlay flap/graft ureteroplasty for the management of long ureteral strictures. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2021, 10, 2871–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tao, C.; Jin, X.; Zhang, H. Dorsal oral mucosa graft urethroplasty for female urethral stricture reconstruction: A narrative review. Front. Surg. 2023, 10, 1146429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jiang, Y.; Yang, C.; Fang, L.; Chen, R.; Li, X.; Jiang, C.; Hu, W.; Chen, H.; Yu, D.; Wang, Y. The application of the “perinephric fat wrapping” technique with oral mucosal graft for the management of ureter repair and reconstruction. World J. Urol. 2024, 42, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, B.W.; Lee, M.; Eun, D.D. Robotic Multiport Buccal Mucosa Graft Ureteroplasty: Tips and Tricks. J. Endourol. 2025, 39 (Suppl. 1), S52–S59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.C.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Bryk, D.J.; Adelstein, S.A.; Stifelman, M.D. Robot-Assisted Ureteral Reconstruction Using Buccal Mucosa. Urology 2015, 86, 634–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahay, S.C.; Kesarwani, P.; Sharma, G.; Tiwari, A. Buccal mucosal graft ureteroplasty: The new normal in ureteric reconstructive surgery—Our initial experience with the laparoscopic and robotic approaches. J. Minim. Access Surg. 2024, 20, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, C.H.; Lin, Y.S.; Weng, W.C.; Lu, C.H.; Hsu, C.Y.; Tung, M.C.; Ou, Y.C. Validation of robotic-assisted ureteroplasty with buccal mucosa graft for stricture at the proximal and middle ureters: The first comparative study. J. Robot. Surg. 2022, 16, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association of Urology. EAU Guidelines on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2024. Available online: https://uroweb.org/guidelines (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Osmonov, D.; Ragheb, A.; Ward, S.; Blecher, G.; Falcone, M.; Soave, A.; Dahlem, R.; van Renterghem, K.; Christopher, N.; Hatzichristodoulou, G.; et al. ESSM Position Statement on Surgical Treatment of Peyronie’s Disease. Sex. Med. 2022, 10, 100459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Garaffa, G.; Sacca, A.; Christopher, A.N.; Ralph, D.J. Circumcision is not mandatory in penile surgery. BJU Int. 2010, 105, 222–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalkin, B.L.; Carter, M.F. Venogenic impotence following dermal graft repair for Peyronie’s disease. J. Urol. 1991, 146, 849–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, P.G.; Somani, B.K.; Rees, R.W. Twenty Years of Plaque Incision and Grafting for Peyronie’s Disease: A Review of Literature. Sex. Med. 2019, 7, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hatzichristodoulou, G.; Osmonov, D.; Kübler, H.; Hellstrom, W.J.G.; Yafi, F.A. Contemporary review of grafting techniques for the surgical treatment of Peyronie’s disease. Sex. Med. Rev. 2017, 5, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadioglu, A.; Sanli, O.; Akman, T.; Ersay, A.; Guven, S.; Mammadov, F. Graft materials in Peyronie’s disease surgery: A comprehensive review. J. Sex. Med. 2007, 4, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucchi, A.; Silvani, M.; Pastore, A.L.; Fioretti, F.; Fabiani, A.; Villirillo, T.; Costantini, E. Corporoplasty using buccal mucosa graft in Peyronie disease: Is it a first choice? Urology 2015, 85, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shioshvili, T.J.; Kakonashvili, A.P. The surgical treatment of Peyronie’s disease: Replacement of plaque by free autograft of buccal mucosa. Eur. Urol. 2005, 48, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cormio, L.; Zucchi, A.; Lorusso, F.; Selvaggio, O.; Fioretti, F.; Porena, M.; Carrieri, G. Surgical treatment of Peyronie’s disease by plaque incision and grafting with buccal mucosa. Eur. Urol. 2009, 55, 1469–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, P.K.; Singh, A.K.; Trivedi, S.; Dwivedi, U.S.; Ramole, Y.; Khan, F.A.; Pandey, M. Role of lingual mucosa as a graft material in the surgical treatment of Peyronie’s disease. Urol. Ann. 2024, 16, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ding, J.; Li, Q.; Li, S.; Li, F.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, J.; Xie, L.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, S. Ten years’ experience for hypospadias repair: Combined buccal mucosa graft and local flap for urethral reconstruction. Urol. Int. 2014, 93, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berglund, R.K.; Angermeier, K.W. Combined buccal mucosa graft and genital skin flap for reconstruction of extensive anterior urethral strictures. Urology 2006, 68, 707–710; discussion 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Li, Y.; Tang, Y.; Chen, W.; Yang, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhou, C.; Li, F.; Zhou, Y. Two-stage repair with buccal mucosa for severe and complicated hypospadias in adults. Int. J. Urol. 2011, 18, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahin, C.; Seyhan, T. Use of buccal mucosal grafts in hypospadia-crippled adult patients. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2003, 50, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pogorelić, Z.; Stričević, L.; Elezović Baloević, S.; Todorić, J.; Budimir, D. Safety and Effectiveness of Triclosan-Coated Polydioxanone (PDS Plus) versus Uncoated Polydioxanone (PDS II) Sutures for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection after Hypospadias Repair in Children: A 10-Year Single Center Experience with 550 Hypospadias. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sufaru, I.G.; Macovei, G.; Stoleriu, S.; Martu, M.A.; Luchian, I.; Kappenberg-Nitescu, D.C.; Solomon, S.M. 3D Printed and Bioprinted Membranes and Scaffolds for the Periodontal Tissue Regeneration: A Narrative Review. Membranes 2022, 12, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Han, C.; Ma, L.; Li, P.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, X.; Tao, T.; Zhao, Y.; Lyu, X.; Zhuo, R.; et al. Robot-Assisted Ureteroplasty with Labial Mucosal Onlay Grafting for Long Left-Sided Proximal Ureteral Stenosis in Children and Adolescents: Technical Tips and Functional Outcomes. J. Endourol. 2024, 38, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa, V.; de Jesus, L.E.; Romao, R.L.; Farhat, W.A.; Lorenzo, A.J.; Pippi Salle, J. Buccal grafts for urethroplasty in pre-pubertal boys: What happens to the neourethra after puberty? J. Pediatr. Urol. 2014, 10, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elifranji, M.; Abbas, T.; Vallasciani, S.; Leslie, B.; Elkadhi, A.; Pippi Salle, J.L. Upper lip graft (ULG) for redo urethroplasties in children. A step by step video. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2020, 16, 510–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, C.D.; Cinà, D.P.; Gonzalez, C.M.; Hofer, M.D. Surgical Approaches and Long-Term Outcomes in Adults with Complex Reoperative Hypospadias Repair. J. Urol. 2018, 199, 1296–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djordjevic, M.; Simsek, A.; Bizic, M.; Stojanovic, B.; Martins, F.; Roth, J.; Purohit, R. “Watch” Shaped Buccal Mucosa Graft for Simultaneous Correction of Severe Chordee and Urethroplasty as a One-Stage Repair of Scrotal Hypospadias. Urology 2020, 137, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avallone, M.A.; Quach, A.; Warncke, J.; Nikolavsky, D.; Flynn, B.J. Robotic-assisted Laparoscopic Subtrigonal Inlay of Buccal Mucosal Graft for Treatment of Refractory Bladder Neck Contracture. Urology 2019, 130, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, O.; Sen, V.; Demir, O.; Esen, A. Subtrigonal Inlay Patch Technique with Buccal Mucosa Graft for Recurrent Bladder Neck Contractures. Urol. Int. 2022, 106, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).