Navigating Pathways in Prostate Cancer Survivorship: A Comprehensive Review of Challenges, Interventions, and Long-Term Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Disparities in Prostate Cancer Diagnosis

2.1. Demographic Profiles of Prostate Cancer Patients

2.2. Impact of Socioeconomic Factors and Insurance Coverage

2.3. Racial Disparities in Diagnosis and Symptom Presentation

3. Disparities in Prostate Cancer Treatment

3.1. Socioeconomic and Insurance-Based Disparities

3.2. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Treatment Utilization

3.3. Access to High-Quality Surgical and Radiation Care

3.4. Intersection of Mental Health and Treatment Disparities

3.5. Implications and Need for Equity Focused

4. Disparities in Prostate Cancer Survivorship

4.1. Implications for Survivorship Care

4.2. Age-Related Differences

4.3. Socioeconomic Influences on Symptom Burden

4.4. Marital Status and Social Support

4.5. Comorbidities and Symptom Burden

4.6. Treatment-Related Symptomatology

- Surgery leads to the most immediate and severe urinary and sexual dysfunction, though bowel function is generally preserved.

- Radiation carries a higher risk of long-term bowel symptoms and gradual sexual decline, with fewer urinary side effects.

- Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) causes systemic side effects, especially in the long term.

- Active Surveillance preserves function but carries the psychological burden of uncertainty.

4.7. Detection Method and Functional Outcomes

4.8. Genetic Predispositions in Symptom Burden and Cancer Management

5. Strategies to Enhance Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care

5.1. Policy and Advocacy

5.2. Community Engagement and Education

5.3. Research and Innovation

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Donnelly, D.W.; Vis, L.C.; Kearney, T.; Sharp, L.; Bennett, D.; Wilding, S.; Downing, A.; Wright, P.; Watson, E.; Wagland, R.; et al. Quality of life among symptomatic compared to PSA-detected prostate cancer survivors—Results from a UK wide patient-reported outcomes study. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilding, S.; Downing, A.; Wright, P.; Selby, P.; Watson, E.; Wagland, R.; Donnelly, D.W.; Hounsome, L.; Butcher, H.; Mason, M.; et al. Cancer-related symptoms, mental well-being, and psychological distress in men diagnosed with prostate cancer treated with androgen deprivation therapy. Qual. Life Res. 2019, 28, 2741–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasorsa, F.; Biasatti, A.; Orsini, A.; Bignante, G.; Farah, G.M.; Pandolfo, S.D.; Lambertini, L.; Reddy, D.; Damiano, R.; Ditonno, P.; et al. Focal Therapy for Prostate Cancer: Recent Advances and Insights. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 32, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagley, A.F.; Anscher, M.S.; Choi, S.; Frank, S.J.; Hoffman, K.E.; Kuban, D.A.; McGuire, S.E.; Nguyen, Q.-N.; Chapin, B.; Aparicio, A.; et al. Association of Sociodemographic and Health-Related Factors with Receipt of Nondefinitive Therapy Among Younger Men with High-Risk Prostate Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e201255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abodunrin, F.; Adeoye, O.; Nelson, N.; Amadi, N.I.; Silberstein, P.T.; Tupper, C. Socioeconomic and demographic patterns associated with treatment delay in prostate cancer: An analysis of the National Cancer Database. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41 (Suppl. 16), e17122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, V.M.; Harrison, M.; Cheng, H.H.; Yu, E.Y.; Morgans, A.K.; Sanda, M.G.; Smith, M.R.; Sartor, O.; Beer, T.M. Improving Research for Prostate Cancer Survivorship: A Statement from the Survivorship Research in Prostate Cancer (SuRECaP) Working Group. Urol. Oncol. 2020, 38, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford-Williams, F.; March, S.; Goodwin, B.C.; Ralph, N.; Israel, M.; Dunn, J. Interventions for Prostate Cancer Survivorship: A Systematic Review of Reviews. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 2339–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, L.; Boorjian, S.A.; Briganti, A.; Klotz, L.; Mucci, L.; Resnick, M.J.; Rosario, D.J.; Skolarus, T.A.; Penson, D.F. Survivorship and Improving Quality of Life in Men with Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2015, 68, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, S.; Feller, A.; Rohrmann, S.; Arndt, V. Health-Related Quality of Life among Long-Term (≥5 Years) Prostate Cancer Survivors by Primary Intervention: A Systematic Review. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowrance, W.; Dreicer, R.; Jarrard, D.F.; Scarpato, K.R.; Kim, S.K.; Kirkby, E.; Buckley, D.I.; Griffin, J.C.; Cookson, M.S. Updates to Advanced Prostate Cancer: AUA/SUO Guideline (2023). J. Urol. 2023, 209, 1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, E.M.; Srinivas, S.; Adra, N.; An, Y.; Barocas, D.; Bitting, R.; Bryce, A.; Chapin, B.; Cheng, H.H.; D’Amico, A.V.; et al. Prostate Cancer, Version 4.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2023, 21, 1067–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smani, S.; Novosel, M.; Sutherland, R.; Jeong, F.; Jalfon, M.; Marks, V.; Rajwa, P.; Nolazco, J.I.; Washington, S.L.; Renzulli, J.F.; et al. Association between sociodemographic factors and diagnosis of lethal prostate cancer in early life. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2024, 42, 28.e9–28.e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abodunrin, F.; Adeoye, O.; Masih, D.; Nelson, N.; Silberstein, P.T.; Tupper, C. Late-stage prostate cancer and associated socioeconomic and demographic factors: A National Cancer Database Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41 (Suppl. 16), e17115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinette, J.W.; Charles, S.T.; Gruenewald, T.L. Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status and Health: A Longitudinal Analysis. J. Community Health 2017, 42, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Press, D.J.; Shariff-Marco, S.; Lichtensztajn, D.Y.; Lauderdale, D.; Murphy, A.B.; Inamdar, P.P.; DeRouen, M.C.; Hamilton, A.S.; Yang, J.; Lin, K.; et al. Contributions of Social Factors to Disparities in Prostate Cancer Risk Profiles among Black Men and Non-Hispanic White Men with Prostate Cancer in California. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2022, 31, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francini, E.; Montagnani, F.; Nuzzo, P.V.; Gonzalez-Velez, M.; Alimohamed, N.S.; Cigliola, A.; Moreno, I.; Rubio, J.; Crivelli, F.; Shaw, G.; et al. Clinical outcomes of abiraterone acetate + prednisone (AA) + bone resorption inhibitors (BRI) versus AA alone as first-line therapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) with bone metastases (BM) in an international multicenter database. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38 (Suppl. 6), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyame, Y.A.; Gulati, R.; Heijnsdijk, E.A.M.; Tsodikov, A.; Mariotto, A.B.; Gore, J.L.; Etzioni, R. The Impact of Intensifying Prostate Cancer Screening in Black Men: A Model-Based Analysis. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2021, 113, 1336–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chornokur, G.; Dalton, K.; Borysova, M.E.; Kumar, N.B. Disparities at presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and survival in African American men, affected by prostate cancer. Prostate 2011, 71, 985–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahal, B.A.; Chen, Y.-W.; Muralidhar, V.; Mahal, A.R.; Choueiri, T.K.; Hoffman, K.E.; Hu, J.C.; Sweeney, C.J.; Yu, J.B.; Feng, F.Y.; et al. Racial disparities in prostate cancer outcome among prostate-specific antigen screening eligible populations in the United States. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 1098–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahal, B.A.; Chen, Y.; Efstathiou, J.A.; Muralidhar, V.; Hoffman, K.E.; Yu, J.B.; Feng, F.Y.; Beard, C.J.; Martin, N.E.; Orio, P.F.; et al. National trends and determinants of proton therapy use for prostate cancer: A National Cancer Data Base study. Cancer 2016, 122, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orom, H.; Biddle, C.; Underwood, W.; Homish, G.G.; Olsson, C.A. Racial or Ethnic and Socioeconomic Disparities in Prostate Cancer Survivors’ Prostate-specific Quality of Life. Urology 2018, 112, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

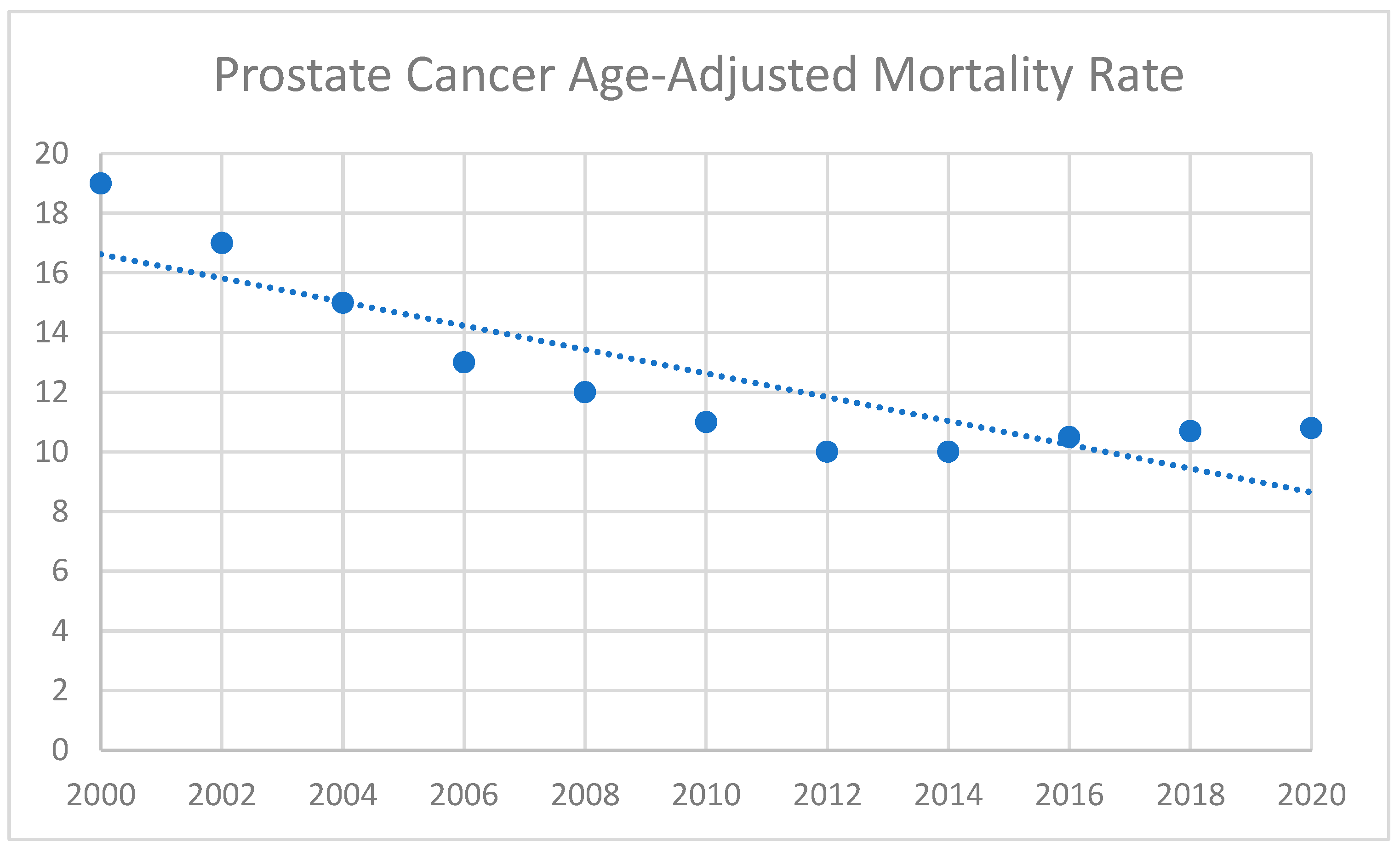

- Du, X.L.; Gao, D.; Li, Z. Incidence trends in prostate cancer among men in the United States from 2000 to 2020 by race and ethnicity, age and tumor stage. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1292577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abudoubari, S.; Bu, K.; Mei, Y.; Maimaitiyiming, A.; An, H.; Tao, N. Prostate cancer epidemiology and prognostic factors in the United States. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1142976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, B.D.T.; Coughlin, E.C.; Nair-Shalliker, V.; McCaffery, K.; Smith, D.P. Socioeconomic differences in prostate cancer treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. 2022, 79, 102164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedland, A.R.; Sanchez Mendez, J.; Liu, L.; Hamilton, A.S.; Zhang, J.; Hwang, A.E.; Ballas, L.; Abreu, A.L.; Deapen, D.; Stern, M.C. Prostate Cancer Disparities in Clinical Characteristics and Survival among Black and Latino Patients Considering Nativity: Findings from the California Cancer Registry. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2024, 33, 1512–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusthoven, C.G.; Carlson, J.A.; Waxweiler, T.V.; Raben, D.; Dewitt, P.E.; Crawford, E.D.; Maroni, P.D.; Kavanagh, B.D. The Impact of Definitive Local Therapy for Lymph Node-Positive Prostate Cancer: A Population-Based Study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2014, 88, 1064–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culp, S.H.; Schellhammer, P.F.; Williams, M.B. Might Men Diagnosed with Metastatic Prostate Cancer Benefit from Definitive Treatment of the Primary Tumor? A SEER-Based Study. Eur. Urol. 2014, 65, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, C.G.; Deville, C. Health Disparities and Inequities in the Utilization of Proton Therapy for Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, C.J.; Kitchen, S.; Bhatia, S.; Bynum, J.; Darien, G.; Lichtenfeld, J.L.; Oyer, R.; Shulman, L.N.; Sheldon, L.K. Policies and Practices to Address Cancer’s Long-Term Adverse Consequences. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2022, 114, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krimphove, M.J.; Cole, A.P.; Fletcher, S.A.; Harmouch, S.S.; Berg, S.; Lipsitz, S.R.; Sun, M.; Nabi, J.; Nguyen, P.L.; Hu, J.C.; et al. Evaluation of the contribution of demographics, access to health care, treatment, and tumor characteristics to racial differences in survival of advanced prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2019, 22, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riviere, P.; Luterstein, E.; Kumar, A.; Vitzthum, L.K.; Deka, R.; Sarkar, R.R.; Bryant, A.K.; Bruggeman, A.; Einck, J.P.; Murphy, J.D.; et al. Survival of African American and non-Hispanic white men with prostate cancer in an equal-access health care system. Cancer 2020, 126, 1683–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandel, A.L.; Simhal, R.K.; Shah, Y.B.; Wang, K.R.; Lallas, C.D.; Shah, M.S. Racial Disparities in Diagnosis and Treatment of Depression Associated with Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Prostate Cancer. Urology 2024, 186, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, C.L.; Thomson, C.A.; Sullivan, K.R.; Howe, C.L.; Kushi, L.H.; Caan, B.J.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Bandera, E.V.; Wang, Y.; Robien, K.; et al. American Cancer Society nutrition and physical activity guideline for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 230–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, B.L.; Lacchetti, C.; Ashing, K.; Berek, J.S.; Berman, B.S.; Bolte, S.; Dizon, D.S.; Given, B.; Nekhlyudov, L.; Pirl, W.; et al. Management of Anxiety and Depression in Adult Survivors of Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 3426–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bower, J.E.; Lacchetti, C.; Alici, Y.; Barton, D.L.; Bruner, D.; Canin, B.E.; Escalante, C.P.; Ganz, P.A.; Garland, S.N.; Gupta, S.; et al. Management of Fatigue in Adult Survivors of Cancer: ASCO–Society for Integrative Oncology Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 2456–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noriega Esquives, B.; Lee, T.K.; Moreno, P.I.; Fox, R.S.; Yanez, B.; Miller, G.E.; Estabrook, R.; Begale, M.J.; Flury, S.C.; Perry, K.; et al. Symptom burden profiles in men with advanced prostate cancer undergoing androgen deprivation therapy. J. Behav. Med. 2022, 45, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esser, P.; Mehnert-Theuerkauf, A.; Friedrich, M.; Johansen, C.; Brähler, E.; Faller, H.; Härter, M.; Koch, U.; Schulz, H.; Wegscheider, K.; et al. Risk and associated factors of depression and anxiety in men with prostate cancer: Results from a German multicenter study. Psychooncology 2020, 29, 1604–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, J.K.; Paul, S.; Cooper, B.; Skerman, H.; Alexander, K.; Aouizerat, B.; Blackman, V.; Merriman, J.; Dunn, L.; Ritchie, C.; et al. Differences in the symptom experience of older versus younger oncology outpatients: A cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, L.; Brederecke, J.; Franzke, A.; De Zwaan, M.; Zimmermann, T. Psychological Distress in a Sample of Inpatients with Mixed Cancer—A Cross-Sectional Study of Routine Clinical Data. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 591771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penson, D.F.; Stoddard, M.L.; Pasta, D.J.; Lubeck, D.P.; Flanders, S.C.; Litwin, M.S. The association between socioeconomic status, health insurance coverage, and quality of life in men with prostate cancer. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2001, 54, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarts, M.J.; Mols, F.; Thong, M.S.Y.; Louwman, M.W.; Coebergh, J.W.W.; Van De Poll-Franse, L.V. Long-term Prostate Cancer Survivors with Low Socioeconomic Status Reported Worse Mental Health–related Quality of Life in a Population-based Study. Urology 2010, 76, 1224–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puri, D.; Pandit, K.; Choi, N.; Rose, B.S.; McKay, R.R.; Bagrodia, A. Striving for Equity: Examining Health Disparities in Urologic Oncology. Cancers 2024, 16, 3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sud, S.; Gerringer, B.C.; Wacaser, B.S.; Tan, X.; Tatko, S.S.; Royce, T.J.; Wang, A.Z.; Chen, R.C. Underascertainment of Clinically Meaningful Symptoms During Prostate Cancer Radiation Therapy—Does This Vary by Patient Characteristics? Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 110, 1122–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, R.; Araújo, N.; Costa, A.; Lopes, C.; Silva, I.; Correia, R.; Carneiro, F.; Braga, I.; Pacheco-Figueiredo, L.; Oliveira, J.; et al. Association between sociodemographic and clinical features, health behaviors, and health literacy of patients with prostate cancer and prostate cancer prognostic stage. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2024, 33, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, L.; O’Leary, E.; Kinnear, H.; Gavin, A.; Drummond, F.J. Cancer-related symptoms predict psychological wellbeing among prostate cancer survivors: Results from the PiCTure study. Psychooncology 2016, 25, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Nepple, K.G.; Kibel, A.S.; Sandhu, G.; Kallogjeri, D.; Strope, S.; Grubb, R.; Wolin, K.Y.; Sutcliffe, S. The association of marital status and mortality among men with early-stage prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy: Insight into post-prostatectomy survival strategies. Cancer Causes Control 2019, 30, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knipper, S.; Preisser, F.; Mazzone, E.; Mistretta, F.A.; Palumbo, C.; Tian, Z.; Briganti, A.; Shariat, S.F.; Saad, F.; Tilki, D.; et al. Contemporary analysis of the effect of marital status on survival of prostate cancer patients across all stages: A population-based study. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2019, 37, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzo, R.M.; Moreno, P.I.; Fox, R.S.; Silvera, C.A.; Walsh, E.A.; Yanez, B.; Balise, R.R.; Oswald, L.B.; Penedo, F.J. Comorbidity burden and health-related quality of life in men with advanced prostate cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakiewicz, P.I.; Bhojani, N.; Neugut, A.; Shariat, S.F.; Jeldres, C.; Graefen, M.; Perrotte, P.; Peloquin, F.; Kattan, M.W. The Effect of Comorbidity and Socioeconomic Status on Sexual and Urinary Function and on General Health-Related Quality of Life in Men Treated with Radical Prostatectomy for Localized Prostate Cancer. J. Sex. Med. 2008, 5, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.M.; Eggener, S.E.; Lipsitz, S.R.; Irwin, M.R.; Ganz, P.A.; Hu, J.C. Effect of Depression on Diagnosis, Treatment, and Mortality of Men with Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2471–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, H.I.; Satariano, W.A.; Thompson, T.; Ragland, K.E.; Van Den Eeden, S.K.; Selvin, S. Initial treatment for prostate carcinoma in relation to comorbidity and symptoms. Cancer 2002, 95, 2308–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.C.; Basak, R.; Meyer, A.-M.; Kuo, T.-M.; Carpenter, W.R.; Agans, R.P.; Broughman, J.R.; Reeve, B.B.; Nielsen, M.E.; Usinger, D.S.; et al. Association Between Choice of Radical Prostatectomy, External Beam Radiotherapy, Brachytherapy, or Active Surveillance and Patient-Reported Quality of Life Among Men with Localized Prostate Cancer. JAMA 2017, 317, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, B.; Pasalic, D.; Barocas, D.A.; Wallis, C.J.D.; Huang, L.-C.; Zhao, Z.; Koyama, T.; Tang, C.; Goodman, M.; Hamilton, A.S.; et al. Patient-reported Outcomes After External Beam Radiotherapy with Low Dose Rate Brachytherapy Boost vs Radical Prostatectomy for Localized Prostate Cancer: Five-year Results From a Prospective Comparative Effectiveness Study. J. Urol. 2022, 208, 1226–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, U.S.; Tenhola, H.; Taari, K.; Aromaa, A. Patients’ perceptions of the negative effects following different prostate cancer treatments and the impact on psychological well-being: A nationwide survey. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 116, 864–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, D.; Shim, S.R.; Kim, C.H. Changes in Beck Depression Inventory scores in prostate cancer patients undergoing androgen deprivation therapy or prostatectomy. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensley, J.G.; Dhillon, H.M.; Evans, S.M.; Evans, M.; Bolton, D.; Davis, I.D.; Dodds, L.; Frydenberg, M.; Kearns, P.; Lawrentschuk, N.; et al. Self-reported lack of energy or feeling depressed 12 months after treatment in men diagnosed with prostate cancer within a population-based registry. Psychooncology 2022, 31, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahal, B.A.; Alshalalfa, M.; Kensler, K.H.; Chowdhury-Paulino, I.; Kantoff, P.; Mucci, L.A.; Schaeffer, E.M.; Spratt, D.; Yamoah, K.; Nguyen, P.L.; et al. Racial Differences in Genomic Profiling of Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1083–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bologna, E.; Ditonno, F.; Licari, L.C.; Franco, A.; Manfredi, C.; Mossack, S.; Pandolfo, S.D.; De Nunzio, C.; Simone, G.; Leonardo, C.; et al. Tissue-Based Genomic Testing in Prostate Cancer: 10-Year Analysis of National Trends on the Use of Prolaris, Decipher, ProMark, and Oncotype DX. Clin. Pract. 2024, 14, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spratt, D.E.; Zhang, J.; Santiago-Jiménez, M.; Dess, R.T.; Davis, J.W.; Den, R.B.; Dicker, A.P.; Kane, C.J.; Pollack, A.; Stoyanova, R.; et al. Development and Validation of a Novel Integrated Clinical-Genomic Risk Group Classification for Localized Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, D.E.; Yousefi, K.; Deheshi, S.; Ross, A.E.; Den, R.B.; Schaeffer, E.M.; Trock, B.J.; Zhang, J.; Glass, A.G.; Dicker, A.P.; et al. Individual Patient-Level Meta-Analysis of the Performance of the Decipher Genomic Classifier in High-Risk Men After Prostatectomy to Predict Development of Metastatic Disease. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 1991–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Kensler, K.H.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, J.; Xu, M.; Pan, Y.; Long, M.; Montone, K.T.; et al. Integrative comparison of the genomic and transcriptomic landscape between prostate cancer patients of predominantly African or European genetic ancestry. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1008641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annala, M.; Vandekerkhove, G.; Khalaf, D.; Taavitsainen, S.; Beja, K.; Warner, E.W.; Sunderland, K.; Kollmannsberger, C.; Eigl, B.J.; Finch, D.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Genomics Correlate with Resistance to Abiraterone and Enzalutamide in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodall, J.; Mateo, J.; Yuan, W.; Mossop, H.; Porta, N.; Miranda, S.; Perez-Lopez, R.; Dolling, D.; Robinson, D.R.; Sandhu, S.; et al. Circulating Cell-Free DNA to Guide Prostate Cancer Treatment with PARP Inhibition. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 1006–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallicchio, L.; Tonorezos, E.; de Moor, J.S.; Elena, J.; Farrell, M.; Green, P.; Mitchell, S.A.; Mollica, M.A.; Perna, F.; Saiontz, N.G.; et al. Evidence Gaps in Cancer Survivorship Care: A Report From the 2019 National Cancer Institute Cancer Survivorship Workshop. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2021, 113, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R.M.; Arora, N.K.; Bradley, C.J.; Brauer, E.R.; Graves, D.L.; Lunsford, N.B.; McCabe, M.S.; Nasso, S.F.; Nekhlyudov, L.; Rowland, J.H.; et al. Long-Term Survivorship Care After Cancer Treatment—Summary of a 2017 National Cancer Policy Forum Workshop. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 1300–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leader, A.E.; Rebbeck, T.R.; Oh, W.K.; Patel, A.V.; Winer, E.P.; Bailey, L.O.; Gomella, L.G.; Lumpkins, C.Y.; Garraway, I.P.; Aiello, L.B.; et al. Adaptation of the socioecological model to address disparities in engagement of Black men in prostate cancer genetic testing. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens Hobbs, K.; Hall, L.L.; Farrington, T.; Moore, A.; Barnett, L.; Aguilera-Funez, N.; Crawford, K.; George, J. Advancing equity in prostate cancer outcomes using community-facing navigation in the cancer continuum of care. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40 (Suppl. 28), 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, H.S.; Saltzstein, S.L.; Shimasaki, S.; Sanders, C.; Downs, T.M.; Robins Sadler, G. Racial/Ethnic and Gender Disparities in Renal Cell Carcinoma Incidence and Survival. J. Urol. 2008, 179, 1704–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prostate Cancer Treatment Program. Available online: https://www.dhcs.ca.gov/services/cancer/PCTP/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Alfano, C.M.; Leach, C.R.; Smith, T.G.; Miller, K.D.; Alcaraz, K.I.; Cannady, R.S.; Wender, R.C.; Brawley, O.W. Equitably improving outcomes for cancer survivors and supporting caregivers: A blueprint for care delivery, research, education, and policy. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thavaseelan, S.; Burnett, A.L.; Chang, S.; Davies, B.; Dy, G.; Greene, K.; Griebling, T.L.; Santiago-Lastra, Y.; McIntire, L.L.; McNeil, B.; et al. AUA Diversity & Inclusion Task Force: Blueprint and Process for Justice, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion. J. Urol. 2022, 208, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polite, B.N.; Adams-Campbell, L.L.; Brawley, O.W.; Bickell, N.; Carethers, J.M.; Flowers, C.R.; Foti, M.; Gomez, S.L.; Griggs, J.J.; Lathan, C.S.; et al. Charting the Future of Cancer Health Disparities Research: A Position Statement From the American Association for Cancer Research, the American Cancer Society, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the National Cancer Institute. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 3075–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Galvez et al. (Current Review) | Narayan et al. (2020) [6] | Crawford-Williams et al. (2018) [7] | Bourke et al. (2015) [8] | Adam et al. (2018) [9] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus | Narrative review on disparities in prostate cancer survivorship | Consensus statement on research priorities | Effectiveness of survivorship interventions | Quality of life and survivorship care | Long-term HRQoL by treatment type |

| Disparities Addressed | Race, SES, insurance, comorbidities, marital status | Research under-representation | Not primary focus | Not addressed | Not addressed |

| Survivorship Domains Covered | Diagnosis, treatment access, symptom burden, genomics, policy, mental health, care coordination | Research gaps in PROs, ADT impact, mental health | Lifestyle, psychosocial, behavioral interventions | Physical activity, diet, psychosocial health | Urinary, sexual, and bowel function by therapy modality |

| Inclusion of Genomic/Precision Medicine | Detailed genomic and tissue profiling implications | Not included | Not included | Mentioned only broadly | Not included |

| Community-Based Interventions | Highlights programs, calls for tailored community outreach | Not included | Not included | Not included | Not included |

| Policy Recommendations | Specific actions for insurance, technology access, and navigation | Calls for more inclusive and long-term survivorship research | Not included | Not included | Not included |

| Primary Contribution | Synthesizes disparities across the care continuum | Identifies survivorship research gaps and sets future priorities | Review of interventions across psycho-oncology and lifestyle domains | Expert review of strategies to improve post-treatment QoL | Systemic synthesis of QoL outcomes stratified by treatment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galvez, A.; Puri, D.; Tran, E.; Zaila Ardines, K.; Santiago-Lastra, Y. Navigating Pathways in Prostate Cancer Survivorship: A Comprehensive Review of Challenges, Interventions, and Long-Term Outcomes. Uro 2025, 5, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/uro5020010

Galvez A, Puri D, Tran E, Zaila Ardines K, Santiago-Lastra Y. Navigating Pathways in Prostate Cancer Survivorship: A Comprehensive Review of Challenges, Interventions, and Long-Term Outcomes. Uro. 2025; 5(2):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/uro5020010

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalvez, Anthony, Dhruv Puri, Elizabeth Tran, Kassandra Zaila Ardines, and Yahir Santiago-Lastra. 2025. "Navigating Pathways in Prostate Cancer Survivorship: A Comprehensive Review of Challenges, Interventions, and Long-Term Outcomes" Uro 5, no. 2: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/uro5020010

APA StyleGalvez, A., Puri, D., Tran, E., Zaila Ardines, K., & Santiago-Lastra, Y. (2025). Navigating Pathways in Prostate Cancer Survivorship: A Comprehensive Review of Challenges, Interventions, and Long-Term Outcomes. Uro, 5(2), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/uro5020010