Abstract

Background/Objectives: Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTs) are commonly reported complications of intravesical Bacillus Calmette–Guerin (BCG) instillation for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer; however, there is limited characterization of the severity of the symptoms. We aim to explore the progression of LUTs with BCG treatment for bladder cancer. Methods: Patients were given the Overactive Bladder Questionnaire Short Form (OAB-q SF) to complete prior to their weekly BCG instillation during their primary six-week induction course. Mean symptom scores were compared for weeks 2 through 6 to baseline scores (week 1) utilizing two-sample tests. Subgroup analysis was conducted to identify cohorts at increased risk for urinary symptom progression. Simple linear regression was performed to determine the change in mean symptom scores over time. Results: A total of 60 patients completed the full six-week induction course and completed the required questionaries. Intravesical BCG administration was associated with no significant change in scores across either the symptom bothers or HFQL surveys, which were taken independently or in aggregate. No statistically significant differences in symptom scores were found between subgroups created based on demographic variables, tumor characteristics, or clinical presentation. Conclusions: Although intravesical BCG may cause acute urinary symptoms, it does not seem to impact a patient’s baseline urinary symptom profile. This is important when counseling patients about the perceived chronic urinary symptom risk associated with BCG treatment.

1. Introduction

In the United States, non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) constitutes approximately 70–75% of newly diagnosed bladder cancer [1]. Intravesical bacilli Calmette–Guerin (BCG) instillation is the standard therapy after transurethral resection of the tumor to reduce recurrence and progression [2,3]. Although its mechanism is not fully understood, intravesical BCG is known to generate an immune response in the urothelium which is an important component of its efficacy [4].

Adjuvant BCG immunotherapy is generally well tolerated, but local urinary symptoms are commonly reported. Adverse effects represent a significant cause for therapy nonadherence [5,6,7]. One chart review found that up to 50% of high-risk patients with NMIBC did not receive maintenance BCG therapy, which was due in large part to the high rate of complications [8]. According to the results of a large-scale study by the EORTC Genito-Urinary Cancers Group, 43.6% and 25.9% of patients starting BCG immunotherapy reported local and systemic adverse events, respectively [9]. These adverse events ranged from irritative lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTSs) to miliary tuberculosis and sepsis and are believed to result either from inflammatory hypersensitivity in urothelial tissue or from the direct invasion of active bacilli [4,10].

While prior studies have evaluated oncologic endpoints and side effect profiles for intravesical BCG immunotherapy following transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT), few have examined patient-reported quality of life metrics. In addition, some trials in this space chose to investigate low-dose BCG therapy, which, when compared to standard BCG therapy, was not found to be noninferior [11,12]. To our knowledge, no studies have evaluated the relationship between standard-dose BCG immunotherapy and patient-reported urinary symptom progression during BCG induction therapy following TURBT. In this paper, we discuss the patient LUTS score from a prospective cohort study of 60 patients with de novo NMIBC who received an initial TURBT between August and December 2021 followed by six weeks of postoperative intravesical BCG immunotherapy at our institution.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants and Data Collection

Patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer requiring Bacillus Calmette–Guerin (BCG) therapy as part of their treatment were enrolled in this IRB-approved study (IRB Number: 1601016896). Exclusion criteria were recent urinary tract infection or prior non-medical intervention for benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH) or overactive bladder (OAB).

Patients were asked to complete both portions of the Overactive Bladder Questionnaire Short Form (OAB-q SF), the OAB-q SF symptom bother and OAB-q SF health-related quality of life (HRQOL), immediately prior to their weekly BCG instillation therapy [13]. The OAB-q SF reduces the OAB-q symptom bother scale from eight to six questions and the HR-QOL scale from 25 to 13 questions [13]. Questionnaires were given for the entirety of BCG treatment, including a six-week induction course and additional maintenance BCG that any patients required. Questionnaires answered prior to the first BCG treatment were indicative of a patient’s baseline urinary symptoms. Only those patients who were able to answer the questionnaires every week of their induction course were included in the final analysis, and patients had to answer at least 80% of the questions across both questionaries to have their weekly questionnaire considered completed.

In addition to the information provided by the OAB-q SF, clinical and pathological data were extracted through a manual chart review. Clinicopathological data included patient related age, sex, race, smoking status, prior history of urinary symptoms, prior history of medication uses for urinary symptoms, history of recurrent UTIs, and stage/grade of bladder cancer. Prior medication use included any patients who had taken any BPH (alpha-1 blockers, 5-alpha reductase inhibitors) or OAB medication (anticholinergic medications, B3 agonists). Patients were considered to have preoperative urinary symptoms if they had any of the following: urgency, frequency, nocturia, or incontinence. Presence of gross hematuria was an independent qualifier.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

We calculated the frequency and percentage of participants according to key study characteristics variables. To determine whether there were significant changes in the mean scores for the BCG and HFQL questions, we used two sample t-tests using SAS Version 9.3 to compare the mean scores for weeks 2 through 6 to baseline scores from week 1. We compared the aggregate score from the OAB-q SF as well as subset scores from the OAB-q SF symptom bother and OAB-Q SF HRQOL portions of the questionnaire. Furthermore, we compared differences in each of the 19 questions administered in the OAB-q SF to determine if BCG treatment seemed to cause the worsening of one specific facet of the OAB-q SF. If patients failed to answer any of the 19 questions on the questionnaire for a given week of their treatment, they were removed from that subset of the analysis. For example, if patients failed to answer a question prior to the third week of their treatment, they were excluded from the analysis comparing mean scores from week 3 and from week 1.

We also compared changes in mean symptoms scores with the data stratified by key study characteristic variables (e.g., age, race, smoking status, stage/grade of BC, prior history of medication use ETC). In these models, the mean difference in scores between week 6 (the final week of the induction course) and week 1 (baseline questionnaire) were modeled. Two sample t-tests were used to compare these mean differences when there were two categories and ANOVA was used when there were more than two categories. We performed linear regression to calculate trends in weekly changes in the total OAB-q SF score and QAB-Q SF symptom bother and HRQOL scores by week.

3. Results

Sixty (n = 60) patients were included in this analysis, all of whom received TURBT followed by induction intravesical BCG immunotherapy. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics are outlined in Table 1. Of note, 24 of 60 patients (40.0%) presented with preoperative urinary symptoms such as urinary frequency, urgency, nocturia or hematuria. Overall, 44 (73.3%) men presented with asymptomatic gross hematuria and two patients reported history of recurrent UTIs. Additionally, 30% of patients were taking medication for urinary symptoms (1 patient taking OAB medications; 16 patients taking BPH medications; 1 patient taking both BPH and OAB medications). The mean (Std. Dev) number of days from primary TURBT to BCG induction was 67.9 (50.1), and the average number of prior TURBTs was 2.1 (0.4).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and characteristics.

Overall, OAB-q SF questionnaire symptom bother scores were not significantly different at the end of induction compared to pre-BCG instillation as seen in Table 2. At week 2 or after one instillation of BCG therapy, there was an overall improvement in bother score (p = 0.04), symptom bother question 1 (“During the past week, how bothered were you by an uncomfortable urge to urinate?”; p = 0.002), HFQL question 2 (“During the past week, how often have your bladder symptoms made you feel like there is something wrong with you?”; p = 0.02), and HFQL question 12 (“During the past week, how often have your bladder symptoms caused you embarrassment?”; p = 0.05). At week 3, there was significant improvement in HFQL question 11 (“During the past week, how often have your bladder symptoms interfered with getting the amount of sleep you needed?”; p = 0.05) and HFQL question 13 (“During the past week, how often have your bladder symptoms caused you to locate the closest restroom as soon as you arrive at a place you have never been?”; p = 0.02). Of note, any statistically significant difference was lost in aggregate across both surveys, and by week 4 onwards, a statistically significant difference could no longer be appreciated across any question or survey. However, a trend toward significance was appreciated for question 3 on the HFQL (“During the past week, how often have your bladder symptoms interfered with your ability to get a good night’s rest?”). In all, the six-week course of intravesical BCG administration was associated with no significant change in scores across either the symptom bother or HFQL surveys taken independently or in aggregate.

Table 2.

Comparison of OAB-q SF at each week of BCG treatment in reference to week 1 of treatment. A negative difference indicates the score of the week is smaller than that of the reference week.

Subgroup analyses based upon age, gender, race, smoking status, grade and stage, preoperative urinary symptoms, preoperative gross hematuria, history of rUTIs, prior medication use, type of medication use, and adherence to maintenance therapy did not significantly differ between cohorts (Table 3).

Table 3.

Difference in OAB symptoms (Total) between week 6 and week 1 for various subgroups.

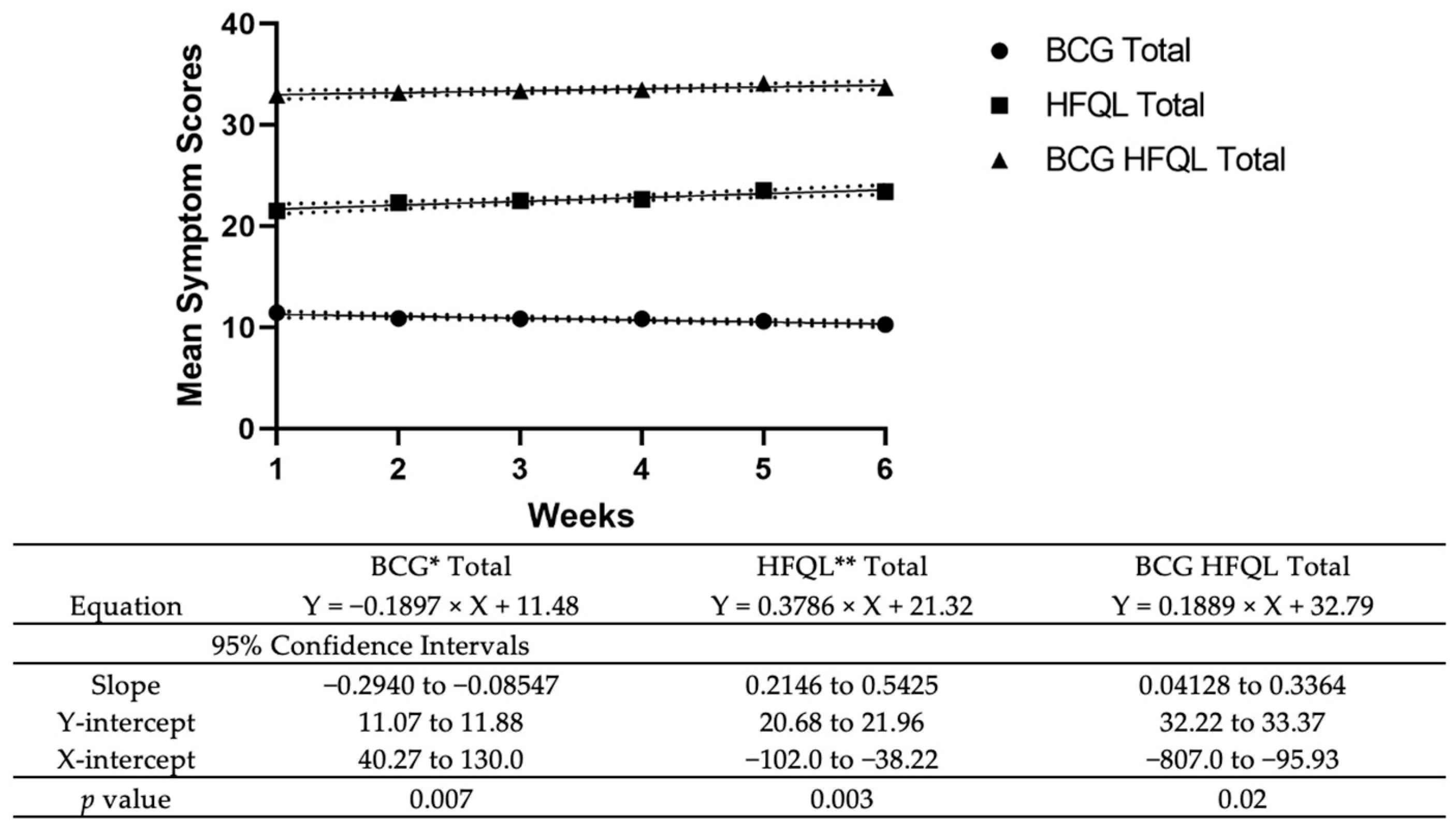

Linear regression demonstrated that there was a significant reduction in the Bother Score (r = −0.19, p = 0.01); however, this was a weak correlation. Additionally, there was a significant improvement in HFQL (r = 0.38, p = 0.003) with BCG administration. For the total score, a significant positive association was found with a slope of 0.19 (p = 0.02) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean symptom score (BCG q Overall, BCG q Symptom Bother, and BCG HFQL) during induction BCG with associated table highlighting regression equations and 95% CI/p-values. * BCG: Bacillus Calmette–Guerin ** HFQL: health-related quality of life.

4. Discussion

Complications as a result of BCG therapy are, unfortunately, common and a substantial reason for the poor compliance of BCG therapy. In a recent trial, 19% of patients who received BCG treatment were dropped from the trial due to treatment-related complications, and only 29% of those enrolled were able to complete the full 3-year course [14]. Another study found that of the 1316 patients enrolled, 915 patients (69.5%) reported complications with the majority (62.8%) of these patients reporting local genitourinary complications [9]. Although local inflammatory urinary side effects are commonplace after BCG instillation, there is relatively little patient-reported data examining the impact of BCG treatment on patients baseline urinary symptoms [15]. Our data demonstrated that there were no significant differences in mean OAB-q SF urinary symptom scores on a week-to-week basis specifically during intravesical BCG induction therapy. Simple linear regression indicated a positive association with a slope of 0.19, and although this was statistically significant, it is unlikely to have a perceivable clinical difference for patients. Collectively, these findings suggest that although patients do experience acute urinary symptoms during induction of BCG intravesical therapy, these symptoms will not persist or exacerbate their baseline urinary symptoms or impact their quality of life.

In a recently published study, examining long-term patient-reported QOL metrics among NMIBC survivors, Jung et al. found that urinary symptom scores were among the lowest across all categories [16]. However, when stratifying by treatment type, urinary symptom QOL scores were similar between patients who received TURBT alone and those who received TURBT + BCG [17]. These findings lend further support to the notion that although BCG may cause irritative symptoms during intravesical administration, it may not influence a patient’s baseline symptom profile in the long term relative to TURBT alone. A recently published study had similar findings showing that patients who received reduced frequency BCG vs. a standard induction course did not have any significant difference in the overall quality-of-life metrics [18]. Part of the disconnect may be attributable to the fact that there is sub-standard reporting of patient-reported outcomes in bladder cancer RCTs when compared to other cancers [17]. By focusing on patient-reported, in addition to clinical outcomes, we may be able to better characterize the urinary symptoms associated with BCG instillation and counsel patients about long-term side effects appropriately.

The current biologic understanding for BCG-induced, local treatment-related adverse effects supports our findings. It is known that BCG exerts its therapeutic effects based on contact with the urothelium leading to a complex inflammatory response with the ultimate release of urinary cytokines that are responsible for the destruction of tumor cells [10]. Hypersensitivity to this immune response is thought to lead to urinary symptoms (dysuria, frequency) commonly experienced after BCG treatment. Thus, one would expect any associated urinary symptoms to self-resolve as the associated immune response is dampened with removal of the catalyst (BCG) [19]. This is consistent with our observation that patients had stable urinary symptoms during BCG induction therapy.

During subgroup analysis, we explored if certain factors predisposed or were protective in causing urinary symptom progression. Our results, as presented in Table 3, did not identify any factors that may be predictive of worsening baseline urinary symptoms. Previous work has shown that smoking can curtail the effects of BCG because it induces a systemic inflammatory response which can subdue the local therapeutic inflammatory effects of BCG therapy [20]. Thus, one would expect that smoking may actually decrease acute urinary symptoms by impairing the immune response to BCG, although we did not notice any effect modification of smoking on urinary symptoms progression in our study. Additionally, patients with the prior utilization of OAB or BPH medications were not at a significantly decreased risk of having urinary symptom progression in comparison to patients who did not take these medications. This is in line with a prior trial which demonstrated that patients with anticholinergic therapy during BCG induction were more likely than controls to experience urinary and non-urinary symptoms [21]. In contrast, a recently published study found that mirabegron administration decreased the frequency of bladder hyperactivity, nocturia, urgency, and incontinence during BCG induction therapy as reported through patient questionnaires [22]. Although our findings were not consistent with the results from this study, it is important to note that patients on OAB medications in our study represented a small subset (3.4%) of the overall study cohort.

Other subgroup analyses of interest were the presence of preoperative urinary symptoms and tumor stage/grade. Our hypothesis was that patients with pre-existing urinary symptoms may be more sensitive to the irritative effects of BCG instillation. This premise was supported by evidence showing that patients with rUTIs and OAB typically have an increased amount of pro-inflammatory mediators within the bladder and urine [23,24,25]. Thus, due to their heightened immune reaction, we believed these patients may have been at higher risk for symptom progression secondary to the local immune-mediated adverse events from BCG therapy. In addition, we expected patients that had cancers with higher stage and grade to also be at a higher risk for urinary symptom progression, since higher stage/grade has been shown to be associated with a higher risk for urinary symptoms at presentation [26]. Our results did not indicate a significant change in urinary symptoms for these subgroups. Although these factors may be predictive of patients’ baseline urinary symptoms, it does not seem to predict urinary symptom progression related to BCG treatment. The results of these subgroup analyses should be interpreted with caution, however, as we recognize that the lack of significance may be attributable to the relatively low sample size, and thus power, in the various subgroups.

Limitations

The major limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size. Our overall cohort consisted of 60 patients followed for six weeks during the BCG induction treatment. The limitations of the sample size were most pronounced during the subgroup analyses where we attempted to determine if certain groups were at greater risk for urinary symptom progression. We were unable to identify any significant contributing factors, even when the mean difference was seemingly substantial, which was primarily due to the low power in these subgroups. For example, only 3.4% of the total cohort had taken OAB medications prior to treatment. Thus, even with a seemingly large difference in mean urinary symptom scores between those who had taken OAB medications and those who had not, the findings were still non-significant due to the significant variance associated with such a small sample size. We did appreciate a trend toward significance in certain questions assessed in this study; larger sample sizes in future studies could help to confirm whether any effect can be seen. Since our data were collected on a volunteer basis, there could be a selection bias in terms of which patients chose to complete the surveys. This study also has a limited follow-up period of six weeks for patient-reported outcomes. Longer-term follow-up in future studies of 3, 6, 9, and 12 months, for example, would help to discern the impacts of chronicity of BCG intravesical therapy and/or repeat TURBT on LUTS. Despite these limitations, however, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the association between BCG treatment and baseline urinary symptom progression. We hope to corroborate these findings through future work, which, together with this study, will provide valuable information that can be used to counsel patients on the chronic impact of BCG treatment on urinary symptoms.

5. Conclusions

Although intravesical BCG may cause acute urinary symptoms, it does not seem to impact a patient’s baseline urinary symptom profile. Patients do not perceive a worsening of their baseline urinary symptoms with intravesical BCG. This is important when counseling patients about the perceived chronic urinary symptom risk associated with BCG treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.C., D.E., K.C.Z., N.B. and C.S.; methodology, B.C. and D.E.; software, Z.S. and A.P.; validation, Z.S. and A.P.; formal analysis, Z.S. and A.P.; data curation, Z.S. and A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.S., A.P. and C.S.; writing—review and editing, B.C., D.E., K.C.Z., N.B. and C.S.; visualization, B.C., D.E., K.C.Z., N.B. and C.S.; supervision, B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Weil Cornell Medical College (IRB Number: 1601016896, Date of Approval: 15 September 2020) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. This is a retrospective study involving de-identified patient data and as a result was exempt from the full institutional review board review per Weill Cornell Institutional Review Board policies. Informed consent was not required for this study design since it was retrospective data from institutional data as outlined by the Weill Cornell Institutional Review Board.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shen, P.-L.; Lin, M.-E.; Hong, Y.-K.; He, X.-J. Bladder preservation approach versus radical cystectomy for high-grade non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 16, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.F.; Pan, J.G. Can intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin reduce recurrence in patients with superficial bladder cancer? A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Urology 2006, 67, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelley, M.D.; Mason, M.D.; Kynaston, H. Intravesical therapy for superficial bladder cancer: A systematic review of randomised trials and meta-analyses. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2010, 36, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asín, M.A.P.-J.; Fernández-Ruiz, M.; López-Medrano, F.; Lumbreras, C.; Tejido, Á.; San Juan, R.; Arrebola-Pajares, A.; Lizasoain, M.; Prieto, S.; Aguado, J.M.; et al. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) infection following intravesical BCG administration as adjunctive therapy for bladder cancer: Incidence, risk factors, and outcome in a single-institution series and review of the literature. Medicine 2014, 93, 236–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamm, D.L.; Blumenstein, B.A.; Crissman, J.D.; Montie, J.E.; Gottesman, J.E.; Lowe, B.A.; Sarosdy, M.F.; Bohl, R.D.; Grossman, H.B.; Beck, T.M.; et al. Maintenance bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy for recurrent TA, T1 and carcinoma in situ transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: A randomized Southwest Oncology Group Study. J. Urol. 2000, 163, 1124–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddens, J.R.; Sylvester, R.J.; Brausi, M.A.; Kirkels, W.J.; van de Beek, C.; van Andel, G.; de Reijke, T.M.; Prescott, S.; Alfred, W.J.; Oosterlinck, W. Increasing age is not associated with toxicity leading to discontinuation of treatment in patients with urothelial non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer randomised to receive 3 years of maintenance bacille Calmette-Guérin: Results from European Organisation. BJU Int. 2016, 118, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddens, J.; Brausi, M.; Sylvester, R.; Bono, A.; van de Beek, C.; van Andel, G.; Gontero, P.; Hoeltl, W.; Turkeri, L.; Marreaud, S.; et al. Final results of an EORTC-GU cancers group randomized study of maintenance bacillus Calmette-Guérin in intermediate- and high-risk Ta, T1 papillary carcinoma of the urinary bladder: One-third dose versus full dose and 1 year versus 3 years of maintenance. Eur. Urol. 2013, 63, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witjes, J.A.; Palou, J.; Soloway, M.; Lamm, D.; Kamat, A.M.; Brausi, M.; Persad, R.; Buckley, R.; Colombel, M.; Böhle, A. Current clinical practice gaps in the treatment of intermediate- and high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) with emphasis on the use of bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG): Results of an international individual patient data survey (IPDS). BJU Int. 2013, 112, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brausi, M.; Oddens, J.; Sylvester, R.; Bono, A.; van de Beek, C.; van Andel, G.; Gontero, P.; Turkeri, L.; Marreaud, S.; Collette, S.; et al. Side effects of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) in the treatment of intermediate- and high-risk Ta, T1 papillary carcinoma of the bladder: Results of the EORTC genito-urinary cancers group randomised phase 3 study comparing one-third dose with full dose a. Eur. Urol. 2014, 65, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, J.; Huang, Y.; Ma, L. Clinical Spectrum of Complications Induced by Intravesical Immunotherapy of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin for Bladder Cancer. J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 6230409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontero, P.; Oderda, M.; Mehnert, A.; Gurioli, A.; Marson, F.; Lucca, I.; Rink, M.; Schmid, M.; Kluth, L.A.; Pappagallo, G.; et al. The impact of intravesical gemcitabine and 1/3 dose Bacillus Calmette-Guérin instillation therapy on the quality of life in patients with nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer: Results of a prospective, randomized, phase II trial. J. Urol. 2013, 190, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokomizo, A.; Kanimoto, Y.; Okamura, T.; Ozono, S.; Koga, H.; Iwamura, M.; Tanaka, H.; Takahashi, S.; Tsushima, T.; Kanayama, H.; et al. Randomized Controlled Study of the Efficacy, Safety and Quality of Life with Low Dose bacillus Calmette-Guérin Instillation Therapy for Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer. J. Urol. 2016, 195, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyne, K.S.; Thompson, C.L.; Lai, J.S.; Sexton, C.C. An overactive bladder symptom and health-related quality of life short-form: Validation of the OAB-q SF. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2015, 34, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvester, R.J.; Brausi, M.A.; Kirkels, W.J.; Hoeltl, W.; Da Silva, F.C.; Powell, P.H.; Prescott, S.; Kirkali, Z.; van de Beek, C.; Gorlia, T.; et al. Long-term efficacy results of EORTC genito-urinary group randomized phase 3 study 30911 comparing intravesical instillations of epirubicin, bacillus Calmette-Guérin, and bacillus Calmette-Guérin plus isoniazid in patients with intermediate- and high-risk. Eur. Urol. 2010, 57, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macleod, L.C.; Ngo, T.C.; Gonzalgo, M.L. Complications of intravesical bacillus calmette-guérin. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2014, 8, E540–E544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, A.; Nielsen, M.E.; Crandell, J.L.; Palmer, M.H.; Smith, S.K.; Bryant, A.L.; Mayer, D.K. Health-related quality of life among non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer survivors: A population-based study. BJU Int. 2020, 125, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerstein, M.A.; Jacobs, M.; Piciocchi, A.; Bochner, B.; Pusic, A.; Fayers, P.; Blazeby, J.; Efficace, F. Quality of life and symptom assessment in randomized clinical trials of bladder cancer: A systematic review. Urol. Oncol. 2015, 33, 331.e17–331.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Straten, C.G.J.I.; Caris, C.; Grimm, M.O.; Colombel, M.; Muilwijk, T.; Martínez-Piñeiro, L.; Babjuk, M.M.; Türkeri, L.N.; Palou, J.; Patel, A.; et al. Quality of Life in Patients with High-grade Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer Undergoing Standard Versus Reduced Frequency of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin Instillations: The EAU-RF NIMBUS Trial. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2023, 56, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koya, M.P.; Simon, M.A.; Soloway, M.S. Complications of intravesical therapy for urothelial cancer of the bladder. J. Urol. 2006, 175, 2004–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.H.; Nepple, K.G.; Peck, V.; Trinkaus, K.; Klim, A.; Sandhu, G.S.; Kibel, A.S. Randomized controlled trial of oxybutynin extended release versus placebo for urinary symptoms during intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guérin treatment. J. Urol. 2013, 189, 1268–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, M.; Tataru, O.S.; Fallara, G.; Fiori, C.; Manfredi, M.; Claps, F.; Hurle, R.; Buffi, N.M.; Lughezzani, G.; Lazzeri, M.; et al. Assessing the influence of smoking on inflammatory markers in bacillus Calmette Guérin response among bladder cancer patients: A novel machine-learning approach. Minerva Urol. Nephrol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.; Wang, D.; Wu, G.; Ma, J.; Wang, T.; Wu, J.; Wang, J. Mirabegron improves the irritative symptoms caused by BCG immunotherapy after transurethral resection of bladder tumors. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 7534–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, T.J.; Mysorekar, I.U.; Hung, C.S.; Isaacson-Schmid, M.L.; Hultgren, S.J. Early severe inflammatory responses to uropathogenic E. coli predispose to chronic and recurrent urinary tract infection. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, L.; Caldwell, A.; Brierley, S.M. Mechanisms Underlying Overactive Bladder and Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuta, A.; Yamamoto, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Gotoh, M.; Egawa, S.; Yoshimura, N. Comparison of inflammatory urine markers in patients with interstitial cystitis and overactive bladder. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2018, 29, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zincke, H.; Utz, D.C.; Farrow, G.M. Review of Mayo Clinic experience with carcinoma in situ. Urology 1985, 26, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).