Previous experimental activities on the HERO-2 facility have shown that the system has several components and operating conditions that may introduce significant uncertainties. Accordingly, a dedicated analysis of the main uncertainty sources was performed, and the most relevant ones are discussed in the following section.

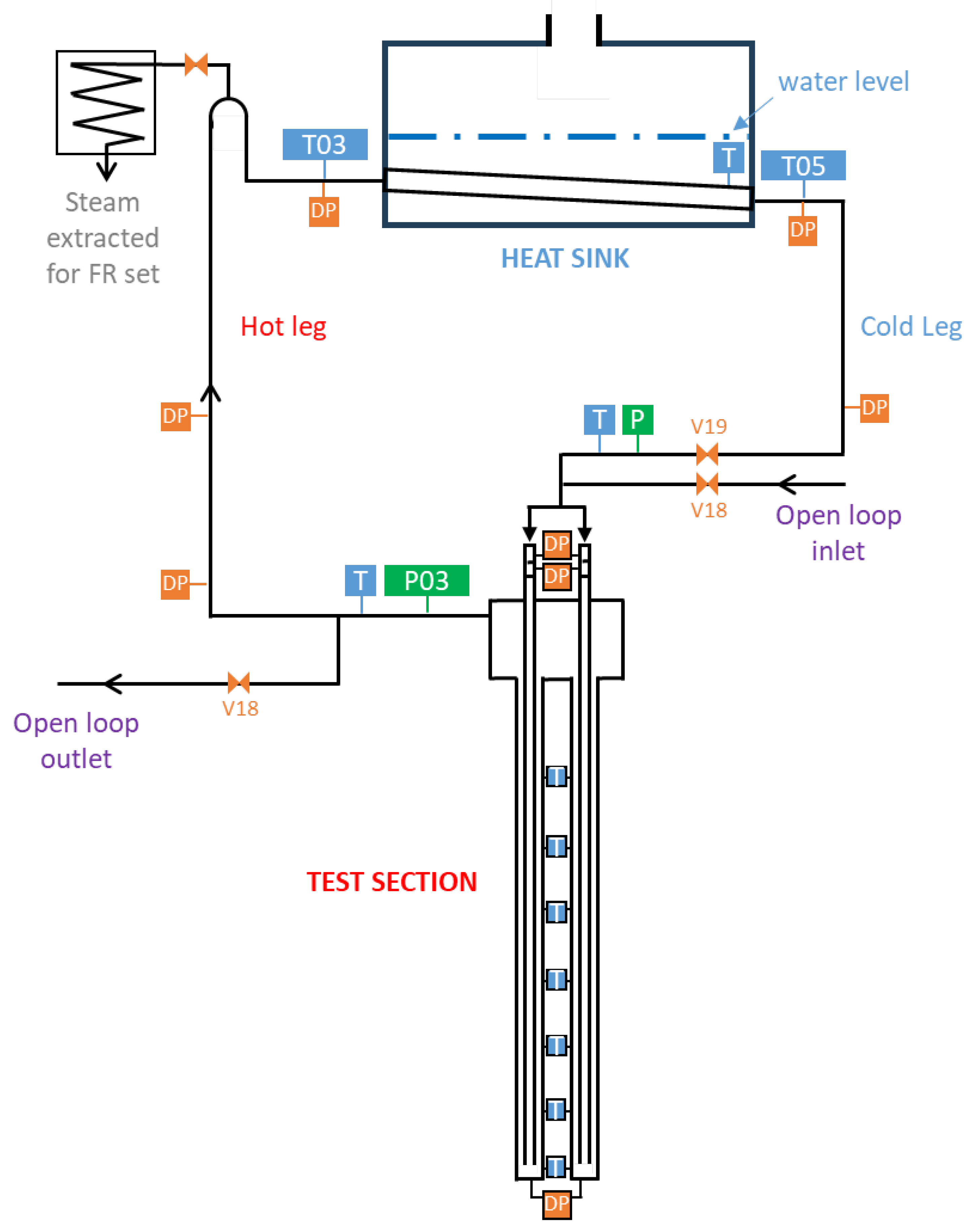

During the experimental campaigns, it was observed that the electrical heaters, which surround the external surface of the test section, gradually lose their sealing efficiency over time and thermal cycling, resulting in a reduced power supply compared to the value required for the specific test. Regarding the FR, at the beginning of each test, the loop is completely filled with water. To reach the correct conditions, a spill occurs along the hot-leg gooseneck, and the discharged tap water is manually weighed to determine the FR value. Although this procedure is simple to perform, it represents a significant source of uncertainty. Furthermore, considering the ratio between the maximum amount of water in the loop (about 20 kg) and the overall size of the facility, even small deviations in the operating parameters can play a relevant role in achieving the correct test conditions.

In order to extend the UA, based on engineering judgement, two other uncertainty parameters have been considered. One is the valve V19 concentrate loss coefficient; this component is fundamental for the correct operation of the system because its activation regulates the shift between the open-extended configuration and the closed-loop configuration. The assumption is the partial failure of the valve, which does not completely open, reducing the flow area. In order to simulate such phenomena, the key value selected for the analysis is the k-loss factor imposed on the valve flow area.

Finally, the air thermal conductivity within the gap between the central descending channel and the external annular channel of the test section has been considered, whose characteristics are not actually known.

The influence of these parameters on the determination of the facility operating conditions at a fixed FR and electrical power input was therefore examined and are evaluated in the subsequent uncertainty analysis.

6.1. Uncertainty Quantification Methodology

In order to better characterize model accuracy and gain key insights into the facility’s behaviour, a UA was performed, still considering the stationary closed-loop test CLOSE18.

In order to perform the UA, the GRS method [

21] has been chosen. The first step of such methodology is the definition of the uncertainty parameter ranges and of the Probability Density Functions (PDFs); it envelops the state of knowledge of all the uncertainty parameters selected. Different types of uncertainty parameters can be chosen: input values (e.g., thermal conductivity of materials), model calibration values, boundary or initial conditions, and numerical values (e.g., min/max time step size). The nodalization uncertainty can be considered within the UA, adding different nodalization schemes to the analysis. Within the present work, such uncertainty has not been introduced in order to focus only on parameters related to the materials and test conditions.

Then, a sufficient number of simulation runs must be defined to ensure statistically meaningful results from the UA. In each simulation, all selected uncertainty parameters are varied simultaneously. The main advantage of this methodology is that it allows the application of statistical techniques in which the number of code runs is considered independent from the uncertainty parameters under investigation. As a result, a Phenomena Identification and Ranking Table (PIRT) is not required, since the ranking naturally arises from the analysis itself. The number of code runs depends on the selected probability content and confidence level of the statistical tolerance limits and is calculated according to the Wilks formula [

22,

23].

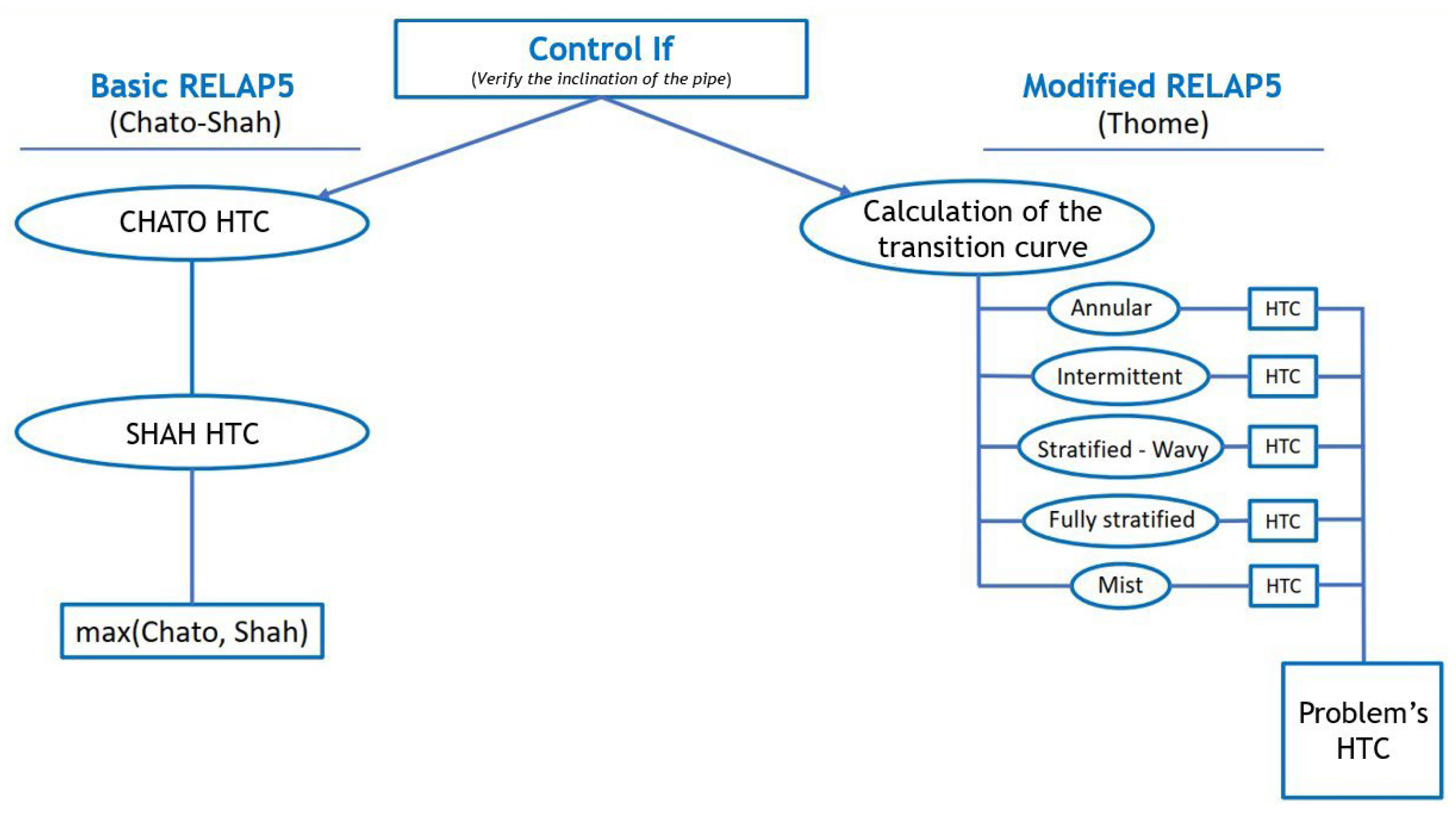

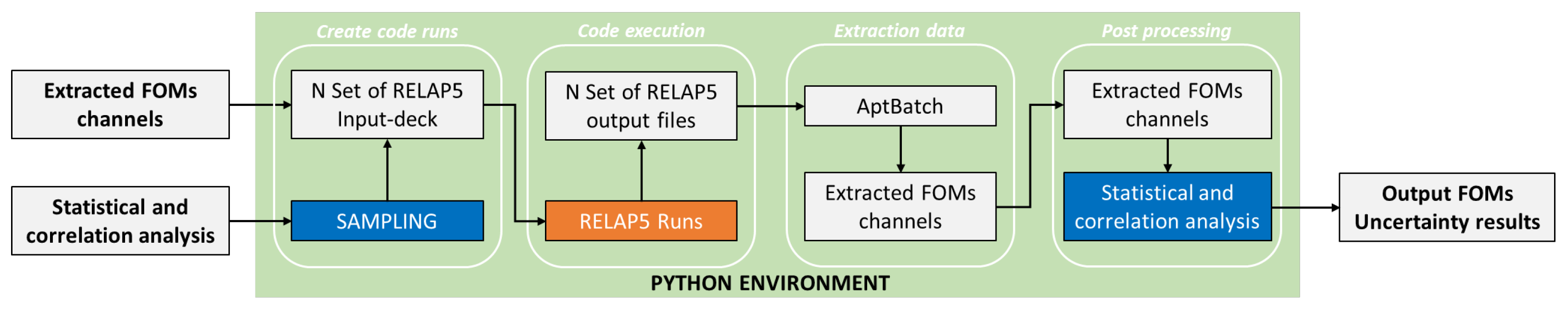

The uncertainty tool used to perform the present UA, for which the scheme of its logic is shown in

Figure 17, was developed and applied thanks to a collaboration between the University of Palermo and the ENEA along the H2020 MUSA project [

24], and it is a fully independent in-house tool written in Python 3. It was born for the MELCOR code application; however, within the present work, it has been adapted for R5 applications.

6.2. Results

Such work aims to perform a UA in order to collect key insights on the facility behaviour, on the statistical correlation between the input uncertainty parameters selected, and the Figures of Merits (FOMs).

Following several past works [

5,

25], the first step of the UA is the selection of the FOMs; in particular, within this work, the selected ones are as follows:

HX exchanged power—FOM_1;

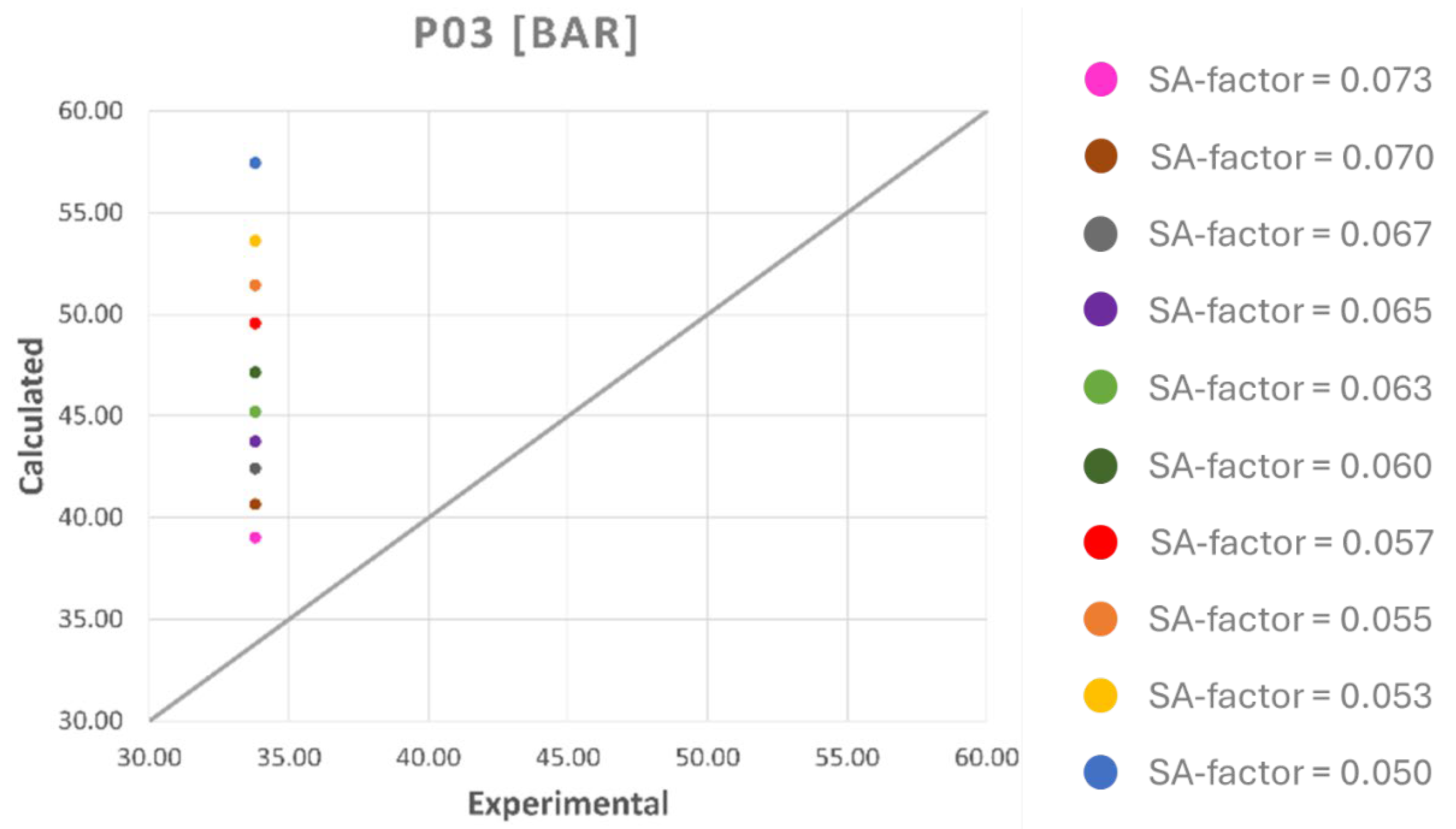

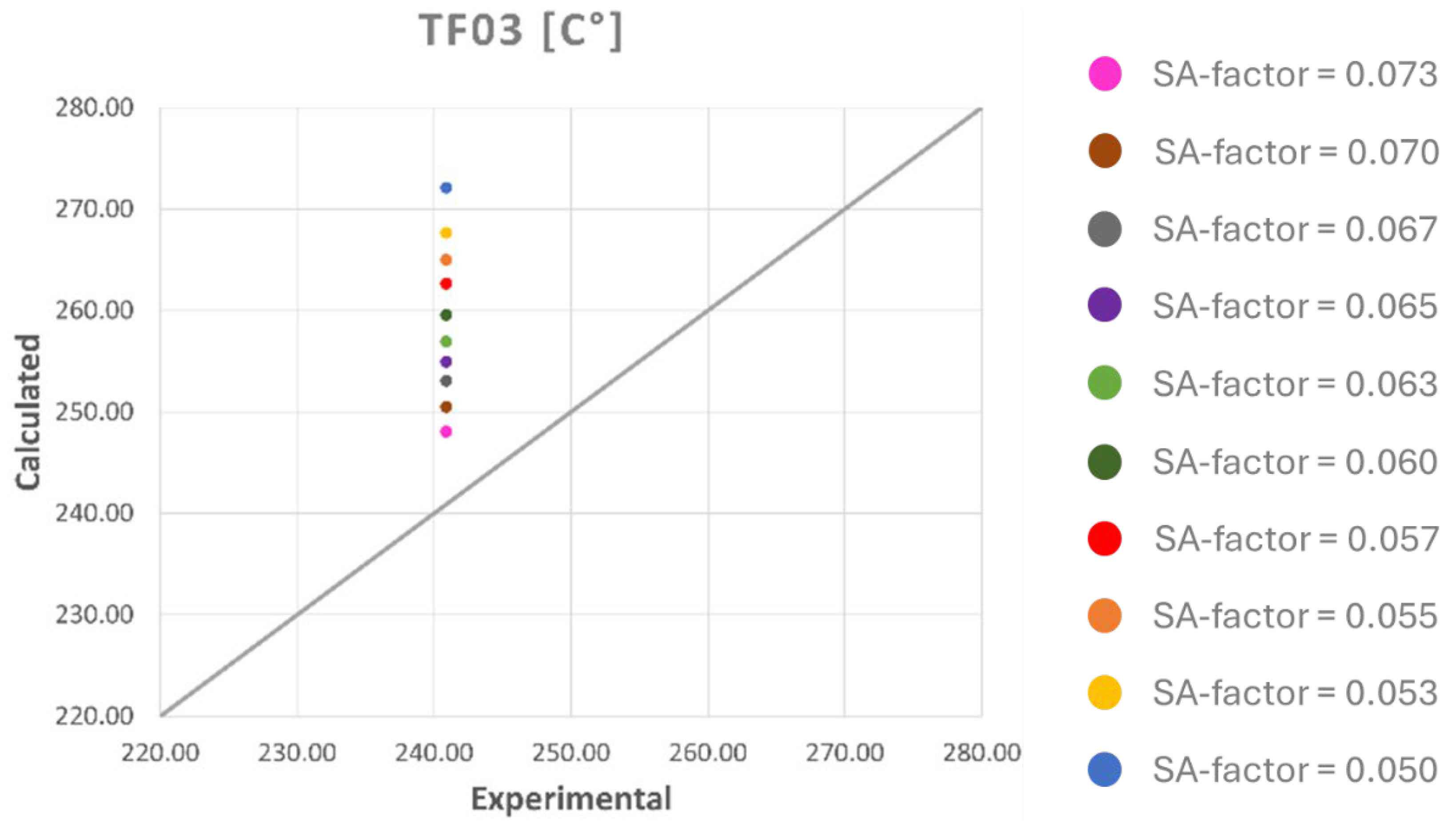

The pressure in the VC (P03)—FOM_2;

The loop mass flow rate—FOM_3.

The three FOMs selected are the key indicators to evaluate the capability of the plant to perform the safety action required. In order to propagate the uncertainty among the selected FOMs, a set of uncertainty input parameters must be defined. In

Table 4, there is an explanation of the defined PDF applied for each input parameter, the type of PDF used, and the lower/upper bound of the selected range.

Considering the Wilks formula [

22,

23], 124 runs were needed to reach probability

and a confidence level

of 95% for each FoM; therefore, in order to be more conservative and considering possible run failures, 150 runs were considered in the analysis.

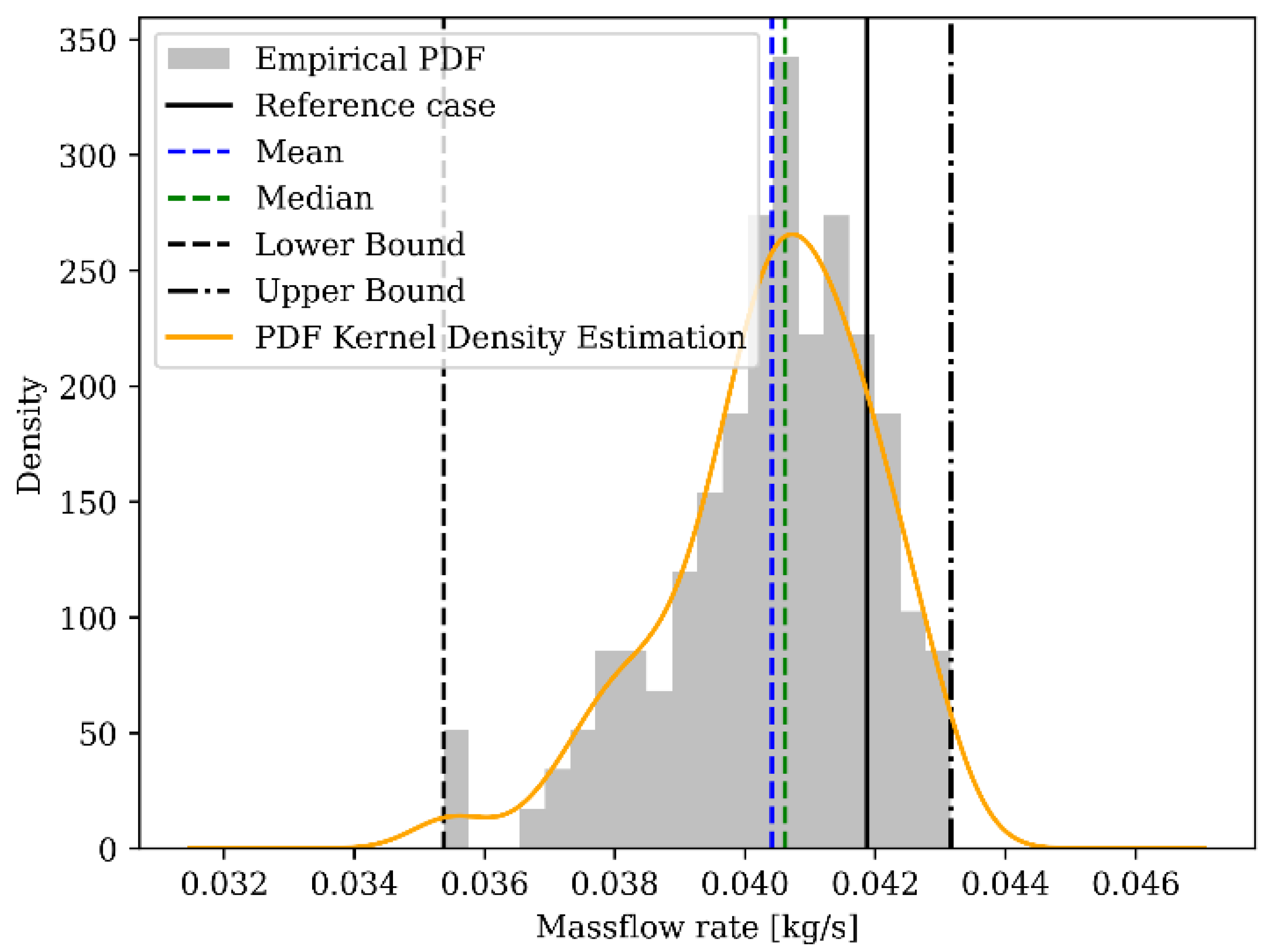

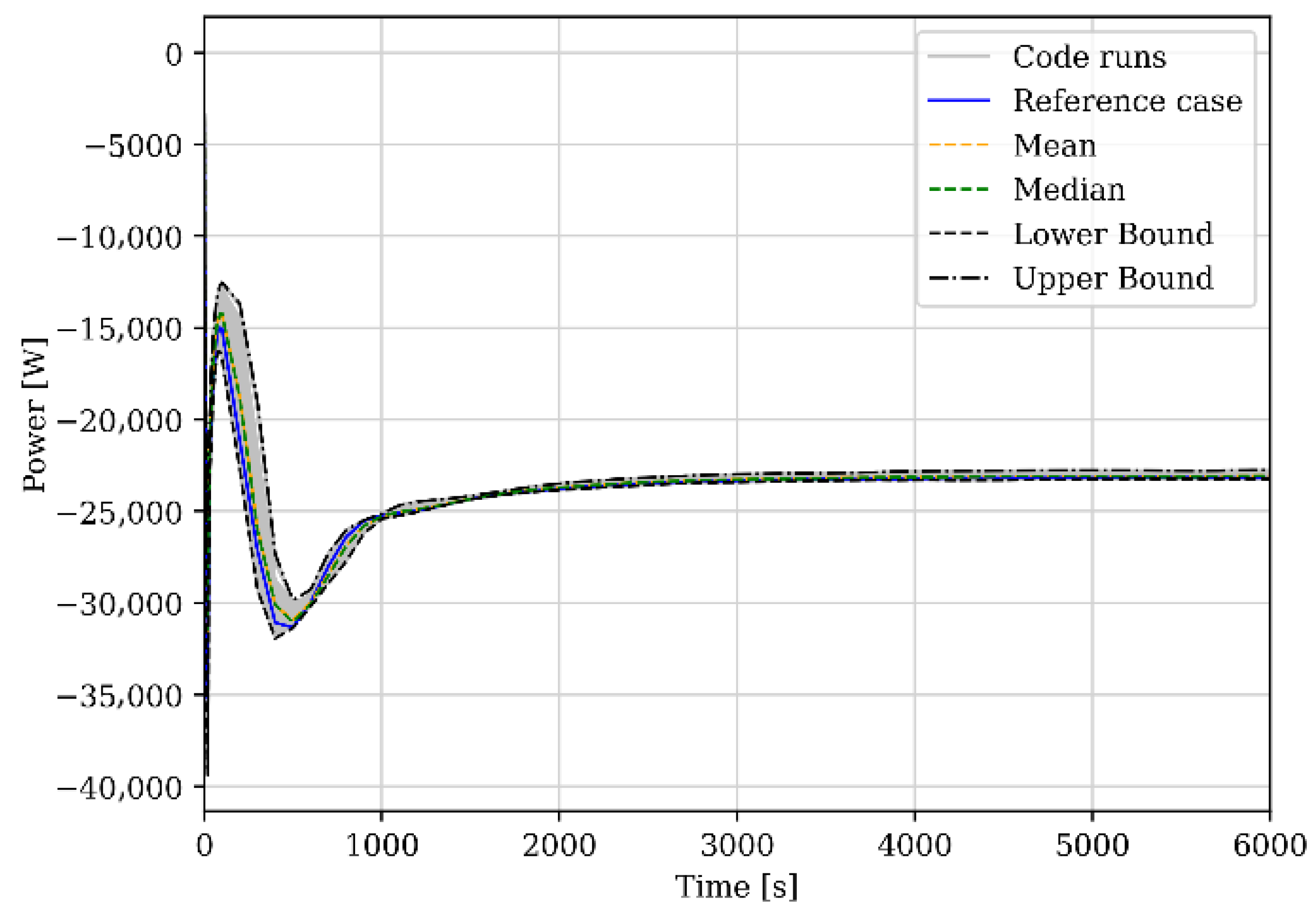

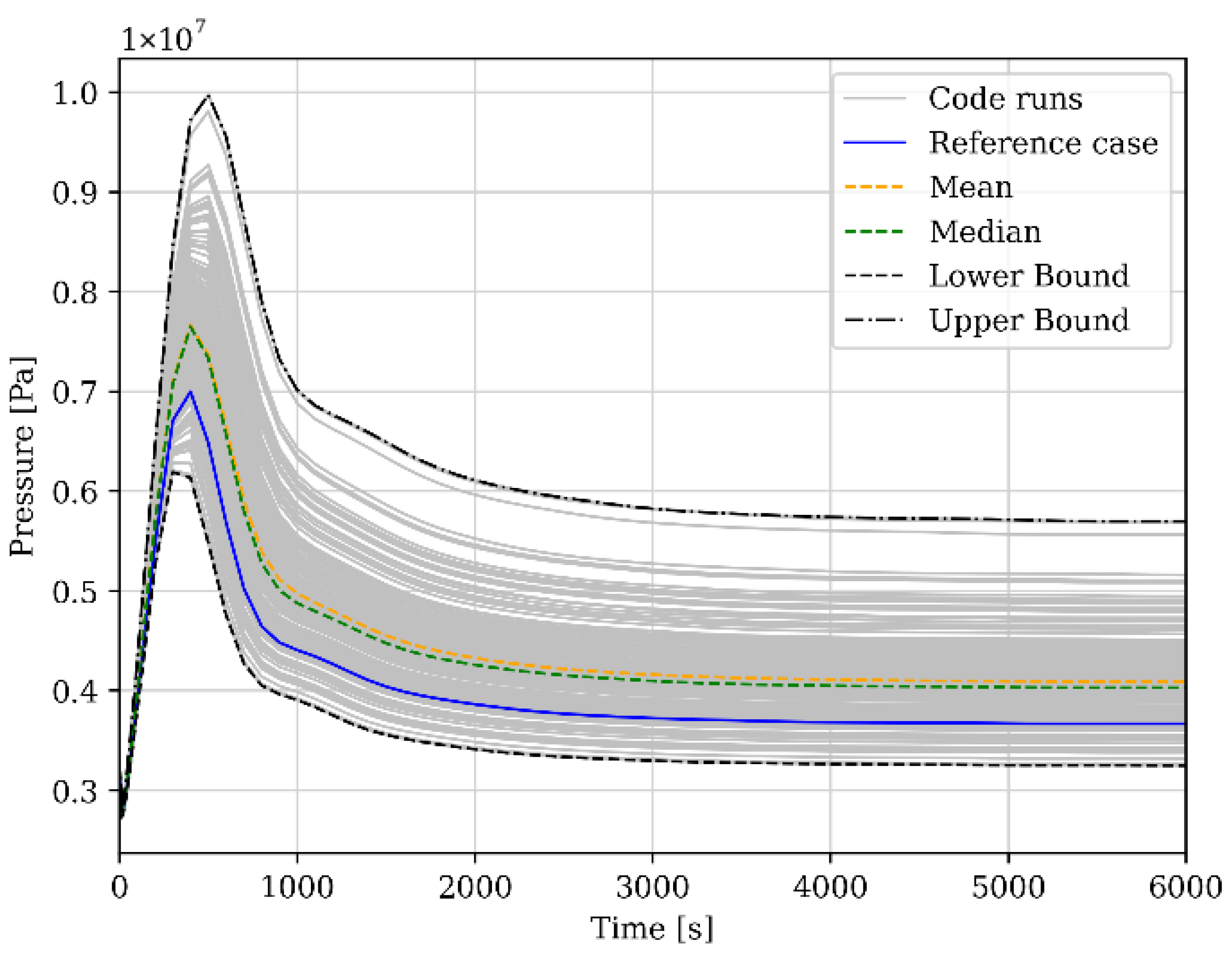

Figure 18,

Figure 19 and

Figure 20 represent the calculated PDF of the FOMs compared to the reference code calculation (the CLOSE18 test with all the reference values for the selected uncertainty parameters) and the calculated statistical parameters, such as the mean, median, and lower and upper bound.

In

Table 5 all the numerical values related to the mean, median, and lower and upper bound are represented; moreover, the kurtosis parameter, indicating the “extremeness” of the distribution tails compared to a normal distribution, and the skewness parameter, indicating the symmetry of the data’s distribution compared to the mean, are represented [

26].

The joint analysis of mean, median, skewness, and kurtosis reveals the underlying nature of the data: where they are concentrated, how they are distributed, and how predictable they are, giving more information about the uncertainty.

All the considerations are summarized in

Table 6.

Observing

Table 6 and focusing on the FOM_1 column, it is possible to detect that the accuracy of the central value is high and the distribution of the population’s assumed values is practically equal to the mean value; moreover, the value of the skewness and kurtosis parameters guarantees a symmetrical normal distribution. For these reasons, the expected range of uncertainties is small, as shown in

Figure 21. Similarly, even with some discrepancies and not properly symmetric behaviour, the same expected range behaviour is predicted for the loop mass flow rate (FOM_3) as shown in

Figure 22. On the contrary, the VC pressure (FOM_2) highlights a non-normal distribution with a consistent difference in the central value; moreover, by observing the skewness and the kurtosis coefficient, it is possible to understand that the PDF has a lower value than the mean value and is closer to the reference value; however, it has an extreme outlier higher than the reference calculation’s value. Therefore, for these reasons, the expected variation range of such an FOM is larger than the other FOMs’ ranges, as shown in

Figure 23.

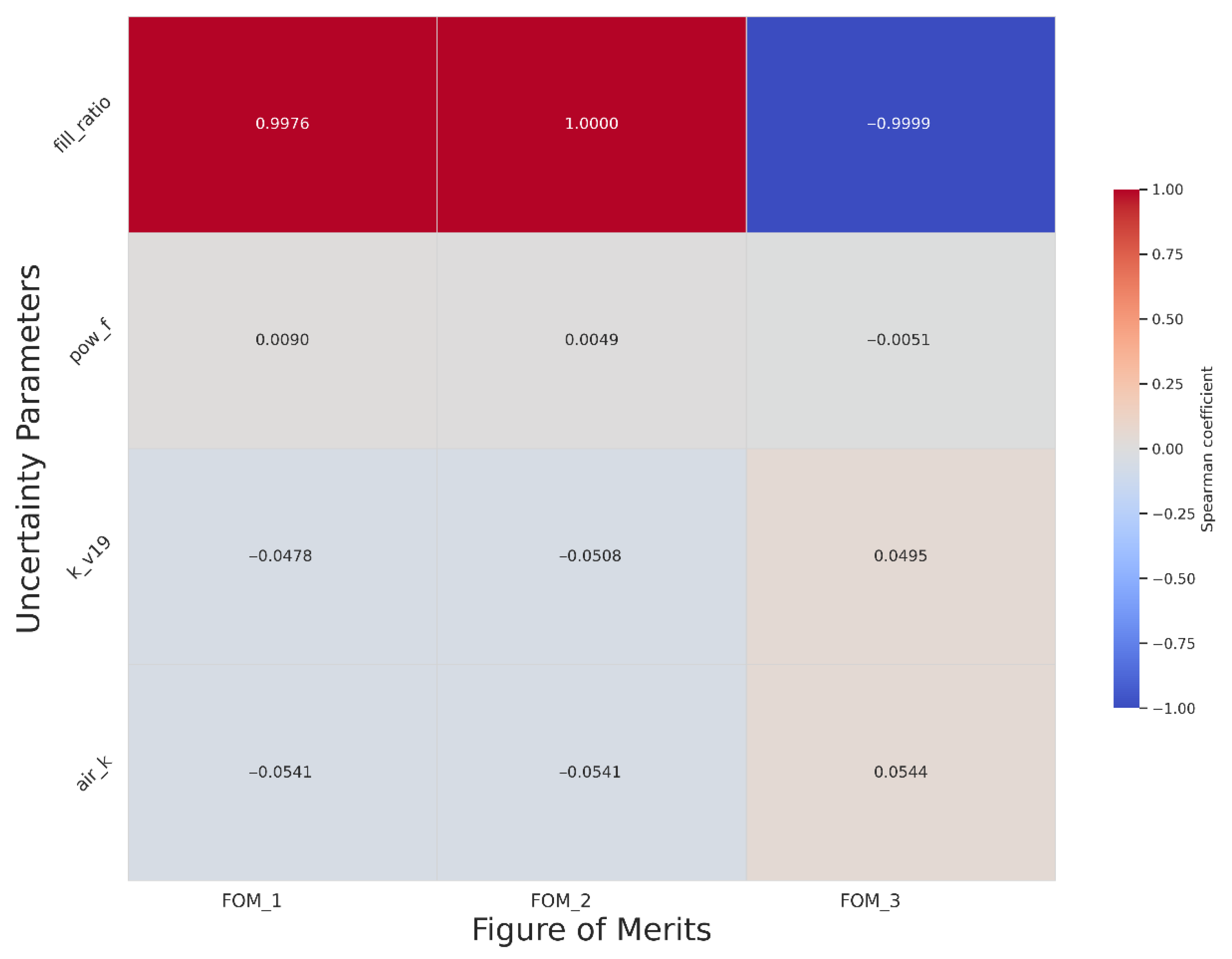

The Spearman’s correlations for each FOM related to each uncertain input parameter have been calculated. In

Figure 24, Spearman’s heat map is represented. The colour represents the intensity and the direction of correlation (red indicates positive correlation, while blue a negative correlation).

From the statistical correlation analysis, it emerges that all three FOMs present a high statistical correlation with the filling ratio. In particular, there is a positive correlation with respect to the HX power and the VC pressure and a negative correlation with respect to the mass flow rate. On the contrary, the other parameters, compared to the selected FOMs, present a non-significant statistical correlation.

The meaning of such considerations is that the system is very sensitive to small variations in the filling ratio at the beginning of the stationary test because it can alter the amount of water in the loop, changing the density gradient, the void fraction distribution, and, therefore, the VC pressure behaviour, altering the thermal-hydraulic condition of the test.

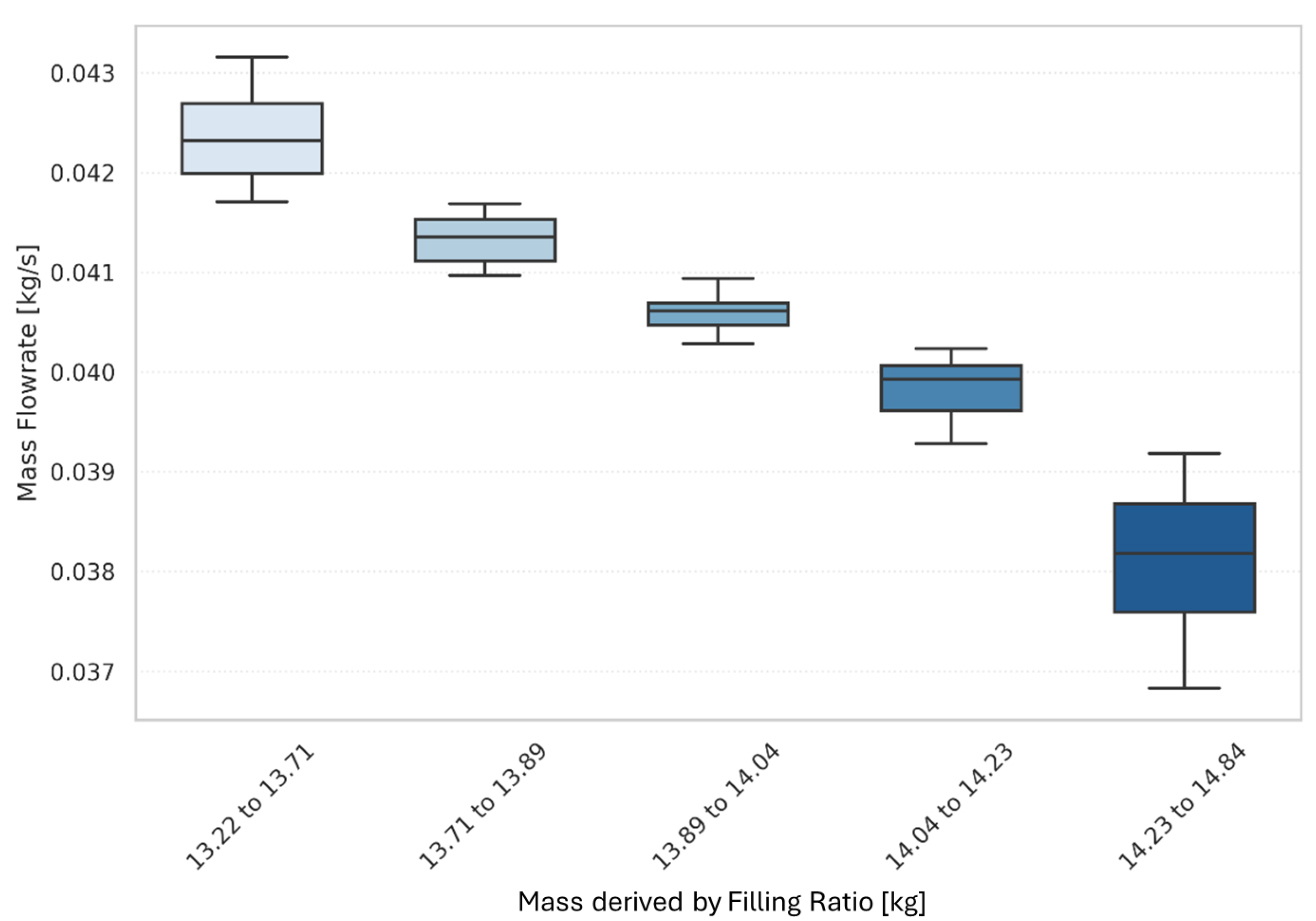

Based on the Spearman results, additional considerations can be performed; in particular, such correlation coefficients determine the degree of a monotonic relationship, if it exists, between two variables but do not indicate for which specific value in the sampled parameter population the uncertainty of the FOMs is higher. Therefore, considering the filling ratio as the only parameter to better analyze due to the high statistical correlation, five groups of such parameter’s values were defined and used in

Figure 25,

Figure 26 and

Figure 27 to create box plots. In particular, the box plot visually summarizes the distribution of a dataset through five key elements: the median (central line), the InterQuartile Range (IQR), which is the box spanning the 1st quartile and 3rd quartile, the whiskers, representing the minimum and maximum value (extending to 1.5 × IQR), and outliers (individual points beyond the whiskers).

In

Figure 25, the box plot representing the FOM_1 HX power dataset in relation to the filling ratio is presented. Observing the five groups, it can be observed that for the filling ratio value groups 13.22–13.71 and 13.89–14.04, there is low variability compared to the central data, especially for the value group 13.89–14.04, where the population within the first and third quartiles is close to the median.

On the other hand, for the value groups 13.71–13.89 and 14.23–14.84, the IQR is very wide, showing a more dispersed distribution further from the median. Therefore, it can be said that, concerning HX power, for high filling ratio values within the sampling range, the uncertainty is high compared to the other groups. On the other hand, even though this is the group with the greatest uncertainty among the five considered, looking at the numerical values of the power, it is possible to observe that, on a practical level, there are minimal variations in power, as also found by observing the range of variation in

Figure 21.

Regarding the dataset relating to FOM_2 VC pressure, shown in

Figure 26, it can be observed that the three central groups have a small IQR with values close to the median and also maximum and minimum values very close to the IQR, meaning that for these filling ratio values, the uncertainty relating to the population is very limited. However, looking at groups 13.22–13.71, representing the range with the minimum values, and 14.23–14.84, representing the range with the maximum sampled filling ratio values, it is possible to observe a significant variation in the IQR with, especially for the range 14.23–14.84, long whiskers of varying lengths, indicating high data dispersion and asymmetry in the distribution of the dataset. The range of variation in the two critical intervals is approximately 5–6 bar, indicating significant uncertainty regarding the determination of the saturation conditions of the system and, therefore, of the thermohydraulic conditions of the water within the loop.

Lastly, considering the FOM_3 mass flow rate, shown in

Figure 27, and observing the entire spectrum of its variation, it can be observed that the range of uncertainty is minimal, as also shown in

Figure 20. In any case, it is possible to focus on the range with the highest values (14.23–14.84), noting the highest dispersion and also an asymmetry in the distribution of mass flow values tending towards the minimum value of the distribution. In addition, it can be observed that as the filling ratio value increases, the trend of the FOM values is negative. This is explained by the fact that the more water is present in the loop, the more the density gradient needed to provide motion to the fluid decreases, decreasing the mass flow rate.