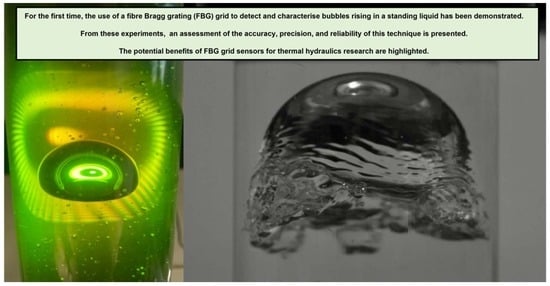

4.1. General Analysis

To reiterate, the parts of the FBG grid’s optical fibres that pass through the fluid domain will be referred to as a chord.

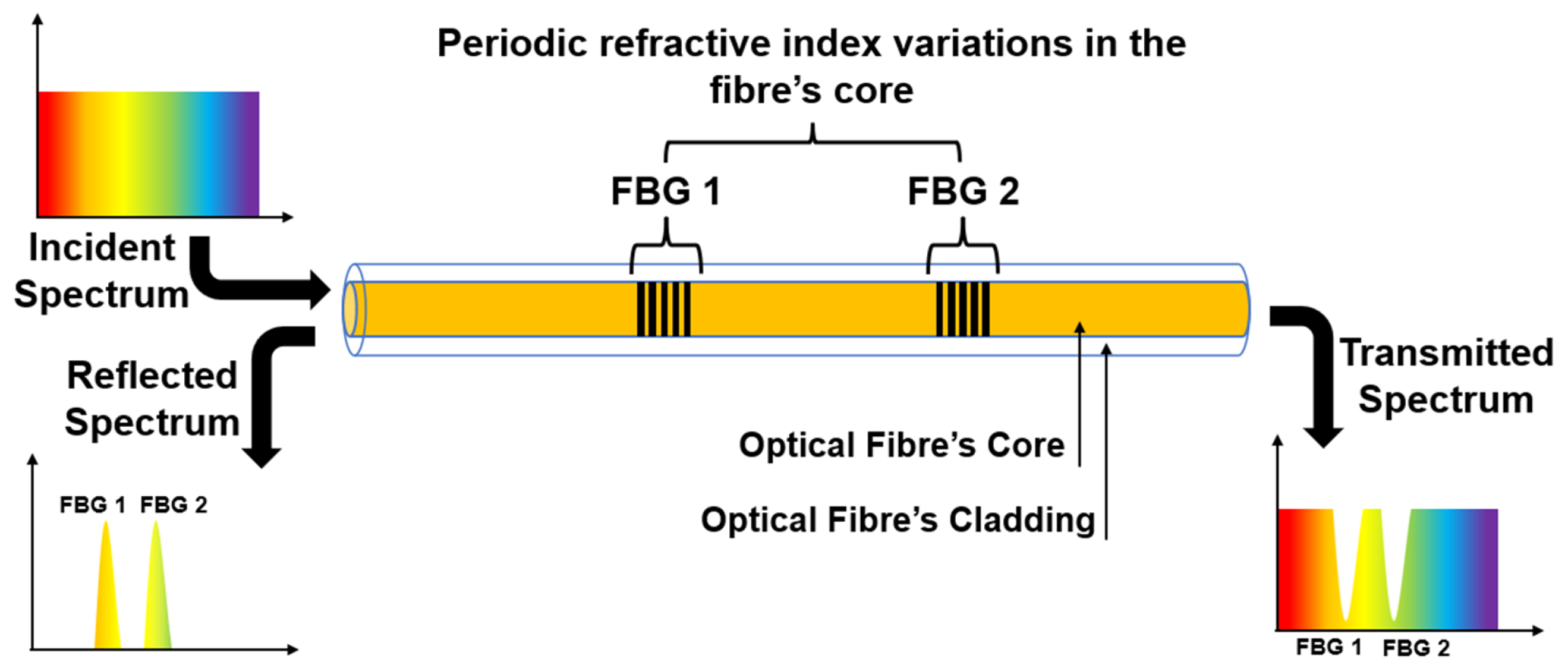

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show the average normalised Bragg wavelength (ANBW) shifts for the water and oil experiments, respectively. These values are produced by calculating the mean average of all the normalised Bragg wavelength shifts of each FBG along a given chord, as shown in Equation (

2).

where

is the average normalised Bragg wavelength along a chord,

is the normalised Bragg wavelength of the

xth FBG on a chord, and

N is the total number of FBG along a given chord.

The light blue lines, either side of the ANBW shift line, represent the spread of normalised Bragg wavelengths used to calculate the ANBW. This was achieved by calculating the standard deviation of the normalised Bragg wavelengths of each FBG along a chord (for each time step). With this value, the ANBW, plus/minus the standard error of the values used to calculate the ANBW, is plotted. Providing an indication of the precision with which the ANBW reflects the average Bragg wavelength shift along a chord.

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show data from the first of the three repeated trials for the air–water and air–oil tests, respectively. The trends and features shown in these graphs are representative of the two subsequent repeated experiments that followed them. The x-axis of

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 has been limited to not show time from t = 0, as before air injection, there was no shift in the ANBW values.

Despite the different viscosity liquids through which the air bubbles travelled,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 share many common features—indicated on these graphs by regions A, B, and C. Firstly, before the pump is activated, there are no additional forces being imposed on the FBG grid’s optical fibres in either experiments. This is represented in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 by the region of no normalised Bragg wavelength change, corresponding to the time before the air injection pump was activated—shown in region A. During this time, the FBG grid is simply sat in the static liquid with no disturbance. Thus, starting from the first data point at t = 0 s, the unstrained reference values are produced that are used to normalise the Bragg wavelength values of each FBG along a chord. This reference value is the mean average Bragg wavelegnth, of each FBG, over the first 1000 data points.

Next, in region B, a difference is seen between the response of the FBG grid in oil (

Figure 6) to its response in water (

Figure 5). The air–oil experiments in region B show a gradual ANBW shift, across all optical fibre chords, implying a source of strain applied across the whole FBG grid. Through analysis of the synchronised high-speed video footage, it is seen that this region corresponds to the upwards flow of liquid beginning after the air injection is started, causing the liquid level in the column to rise as the liquid is displaced by the injected air. This upwards flow will impart a hydrodynamic force against each optical fibre chord, straining the FBGs, and increasing their Bragg wavelength until the maximum upwards flow rate is achieved. After this, the ANBW plateaus on a new flow-strained value. However, this gradual ANBW shift is not observed in

Figure 5’s region B. This is likely because of the different viscosities of the liquid phases in the air–water and air–oil experiments. Because water (at 15 °C) is approximately fifteen times less viscous than the 20W50 automotive oil used in these experiments, when the air injection pump is activated, the water more easily flows around the FBG grid than than the oil, thus imparting less force against the optical fibres when the air is injected, and offering a possible explanation of why no meaningful additional strain is shown in

Figure 5’s region B.

After region B, region C shows a series of peaks corresponding to the times when large air bubbles interact with and pass through the FBG grid. As 60 s of data for each trail has been recorded, for ease of presentation,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 have been limited to only show the first five large air bubbles that reach the sensor. Through subsequent analysis of the width, timing, and shape of these peaks, it is possible to deduce dimensional properties of the bubbles passing through the FBG grid. In the following sections, this sensing principle, and how it can be used to measure the properties of air bubbles, will be discussed.

Next, an anomalous response shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 is the larger and more variable ANBW shifts of chord 7 compared to what its position in the fluid cross-section would suggest. This behaviour is particularly present in the air–oil data where this behaviour is consistent across all three trials. Although no definitive explanation was identified, we speculate this behaviour is caused by uneven compression of the chord between the LCIR’s flanges. This is because a torque wrench was not used to tighten the FBG grid’s mounting bolts, and from possible non-uniform application of sealant around the fibre. This is significant because this chord was located near a flange bolt hole. Supporting this interpretation, subsequent experiments conducted after replacing sealant and using a torque wrench showed no abnormal behaviour, with chord 7 responding similarly to the other chords. This suggests the unexpected response was most likely due to the installation conditions, rather than from the fluid or a fabrication defect.

Figure 5.

Air–water experiments trial 1 results: variation of the average normalised Bragg wavelength along each chord of the FBG grid.

Figure 5.

Air–water experiments trial 1 results: variation of the average normalised Bragg wavelength along each chord of the FBG grid.

Figure 6.

Air–oil experiments trial 1 results: variation of the average normalised Bragg wavelength along each chord of the FBG grid.

Figure 6.

Air–oil experiments trial 1 results: variation of the average normalised Bragg wavelength along each chord of the FBG grid.

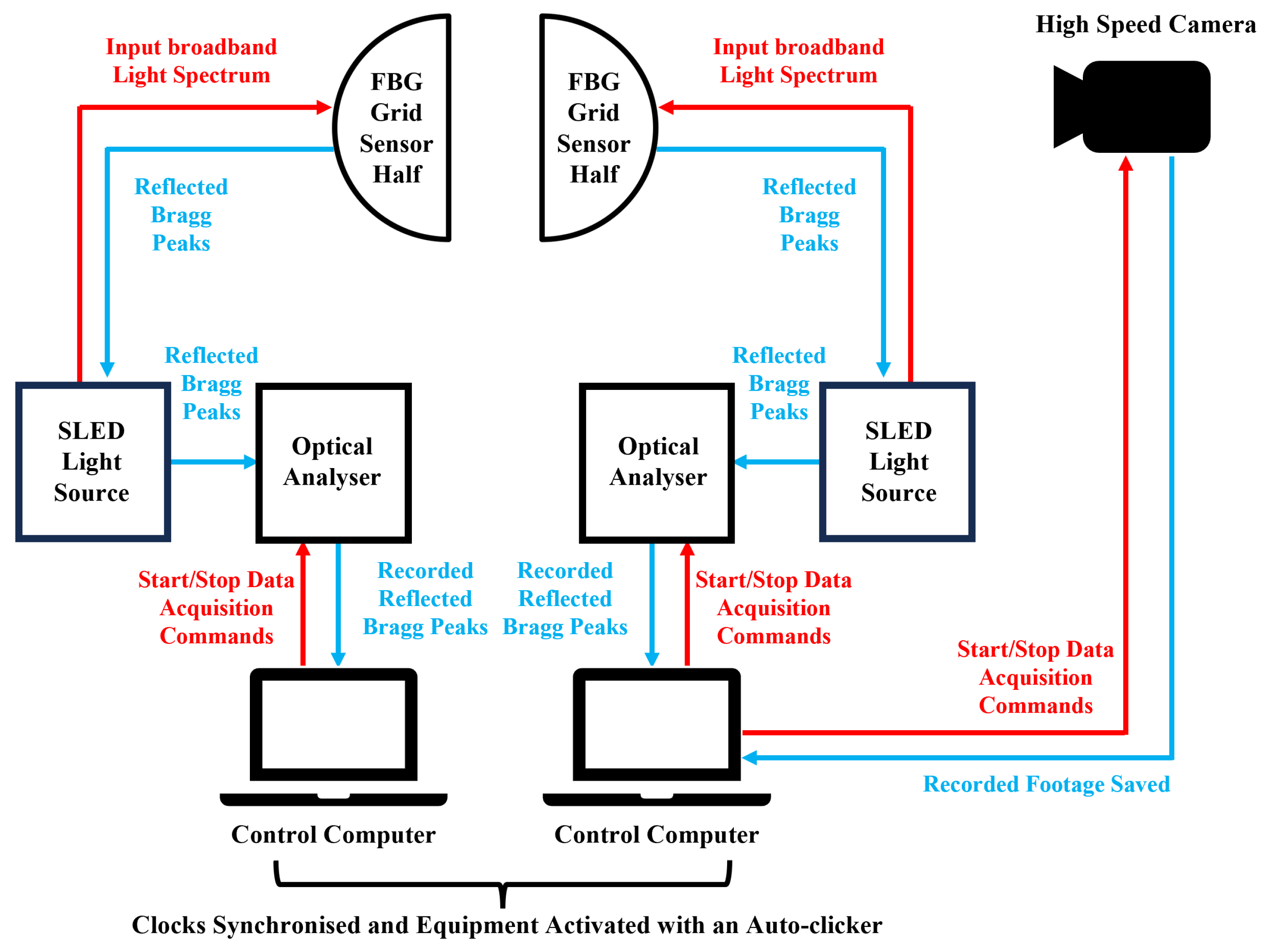

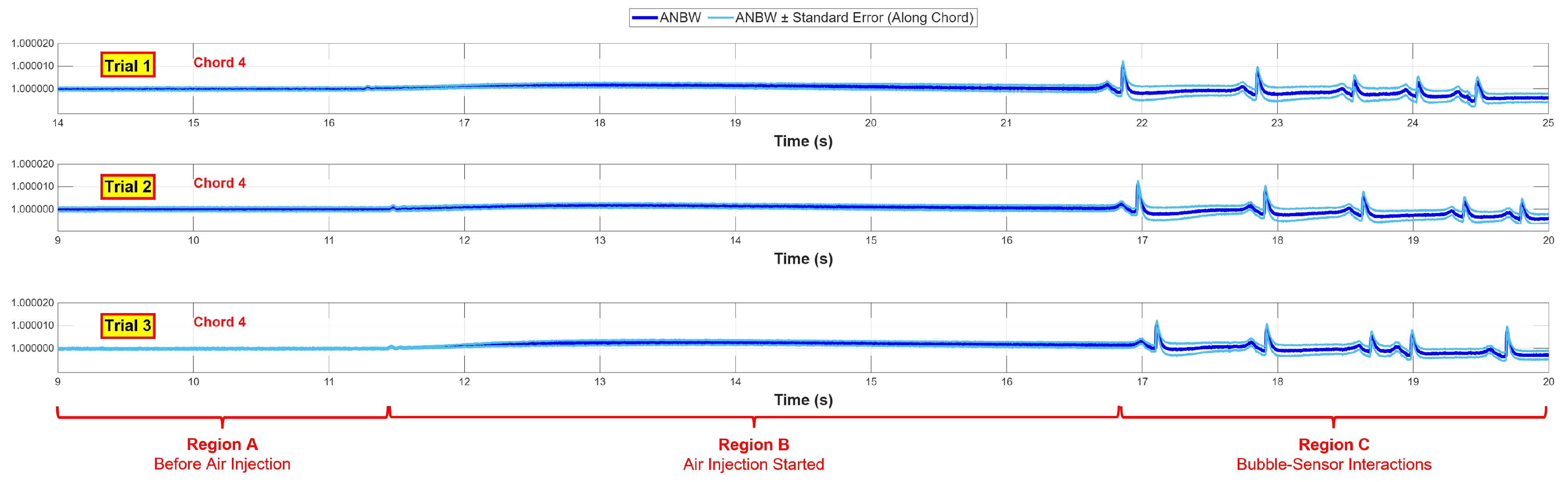

Finally, to demonstrate the cross-trial consistency of the results presented from trial 1,

Figure 7 shows a comparison of the ANBW shift along chord 4 in trials 1–3 of the air–oil experiments. Just as with

Figure 5 and

Figure 6,

Figure 7 is restricted to not show time from t = 0, but similarly shows the response of the FBG grid from just before air injection is started, until after the first five large air bubbles have passed through the sensor. Despite the difference in timings between the start of data capture and air injection between the trials, this example comparison shows the consistency of the FBG grid’s response between the repeated trails. As shown in

Figure 7, each trial features the same three regions congruent with regions A, B, and C observed in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. Furthermore, as will be discussed in

Section 4.2, trials 1–3 show a multi-peak ANBW shift that occurs when bubbles pass through the FBG grid, supporting this later analysis of bubble–sensor interactions. This includes the multi-peak ANBW shifts being of similar magnitude, as expected from the consistent size of the bubbles produced in the air–oil experiments.

4.2. Analysis of a Single Bubble

In the works of Zamarreño et al. [

10], an FBG grid is used to study air–water multiphase flows. In these works, where both the liquid and gas phases are flowing through horizontal pipes, bubbles are detected by a decrease in the measured Bragg wavelength shift as the bubbles pass through the FBG grid. This is because, when Zamarreño et al.’s sensor is engulfed by a large air bubble, the hydrodynamic force acting against the FBG grid decreased, which also decreases the strain along each of the grid’s chords, reducing the Bragg wavelength shift. After passing through the sensor, the Bragg wavelength shift (and the strain along the grid’s chords) then returns to its initial flow-strained condition. However, in the experiments presented in this paper, clear increases in Bragg wavelength shift are observed when air bubbles interact with the FBG grid—in contrast to the results published by Zamarreño et al., implying a variant sensing principle and interaction process is present when the liquid phase is stagnant.

A common response seen in both

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, as well as shown in the cross-trial comparison in

Figure 7, is a multi-peak ANBW shift when a large air bubble passes through the sensor. Insights into understanding the sensing principle and behaviour of an FBG grid can be gained through analysing this response. However, due to the design of the LCIR rig, and the requirement for the FBG grid sensor to be compatible with installation in other facilities in the future, it was not possible to position the high-speed camera to view the sensor as bubbles passed through it. Therefore, the following analysis of the ANBW shift is based on fluid and bubble dynamics theory, rather than direct observation. Future work will be aimed at rectifying this to attempt to corroborate this analysis.

Figure 8 shows an isolated view of the ANBW shifts from

Figure 5 that correspond to the first air bubble passing through the FBG grid. Given that each increase in ANBW implies an increase in strain along an FBG (see Equation (8)) the multi peak response suggests that when a bubble passes through an FBG grid, it imparts force on the optical fibres in several stages, rather than through a single action. In part (i) of

Figure 8, before an air bubble reaches the FBG grid, the ANBW does not shift from its baseline or flow-strained value. Next, part (ii) occurs when the air bubble first begins to interact with the sensor, as estimated from the bubble’s velocity calculated from the high-speed camera footage. This region shows a gradually increasing ANBW shift, implying an increase in strain along the optical fibre chord. This is likely because as a large air bubble reaches the FBG grid, it will impart a force on the sensor through interactions with the bubble’s surface—and perhaps, as well, through the accelerated displaced liquid around the bubble.

Figure 8.

Magnified view of the ANBW response produced by the first air bubble from trial 1 of the air–water experiments.

Figure 8.

Magnified view of the ANBW response produced by the first air bubble from trial 1 of the air–water experiments.

After this, as the bubble continues to move upwards through the sensor, eventually its retaining surface tension effects will be overcome and it will either engulf the optical fibres, or the bubble will begin to fragment. This could explain the decrease in ANBW shown in

Figure 8’s part (iii), because if there is no longer a defined surface acting against the FBG grid, then the force imparted on the sensor will be less, leading to a drop in strain along an optical fibre chord.

Following this, part (iv) shows a gradual increase in ANBW to a local maximum, before rapidly decreasing—potentially caused by the lower surface of the bubble reaching the FBG grid. This is because, after the sensor has become engulfed, the bubble will continue to rise through the FBG grid until its lower surface reaches the fibres. Here, it will begin to act against the FBG grid before passing through or fragmenting. This would impart force onto the sensor, straining the optical fibres, before quickly decreasing when the bubble has completely passed through the FBG grid.

Finally, behind the first large air bubble, there are smaller bubbles and turbulent liquid travelling upwards in its wake. These will, in turn, interact with the FBG grid as they flow through, likely causing small vibrations manifesting as fluctuating increases in strain. This can be seen in

Figure 8’s part (v), where following the final large ANBW shift, for 0.6 s, the ANBW subtly oscillates before returning to a consistent baseline.

This multistage ANBW response to a large air bubble, as presented in this analysis, can also be seen in the other central chords shown in

Figure 8. Additionally, throughout

Figure 6 (see chords 3–5) and

Figure 7, multi-peak ANBW responses that approximately follow the outline of this single bubble analysis can also be identified. However,

Figure 8’s chords 1 and 8 do not show this ANBW shift, and chords 5 and 6 show a much weaker response. As will be discussed in

Section 4.5, from review of the high-speed camera data, chords 1 and 8 are situated outside the outer diameter of the air bubble interacting with the sensor at this time. Therefore, the lack of response from these FBGs can be explained by the bubble’s surface not acting against these fibre chords. Conversely, the weaker response from chords 5 and 6 remains more anomalous. Given the dimensions of the large air bubble, it should have interacted with these more central fibre chords, especially given that chord 7’s FBGs experienced larger magnitude ANBW shifts. A possible explanation for this could arise from errors in the fabrication process of the FBG grid, where these chords might have inadvertently become pretensioned differently to the other parts of the sensor. Leading to the FBGs on these chords having a weaker response to the bubble-imposed strain. Alternatively, upon reaching the sensor, the air bubble may have become deformed in a manner that unequally spread its surface; but given chord 6’s weaker response in all air–oil and air–water tests, this is less likely. In either case, future research is needed to study the effects of pretensioning on the response of an FBG grid, as well as fully transparent test section studies to observe the deforming and fragmenting effects of an FBG grid on bubbles in multiphase flow. From these future works, explanations of these anomalous results might be identified. In addition, when manufacturing future FBG grids, the optical fibres could be connected to an SLD and optical analyser whilst being pretensioned, enabling quality control to ensure that all fibre chords are pretensioned equally.

4.3. Measurement Precision

The ANBW shift lines on

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 (dark blue), are plotted alongside lines (light blue) showing the ABNW plus/minus the standard error. As each ANBW data point is the mean average of the normalised Bragg wavelength of every FBG along a given chord (at each time step) the standard error provides a statistical measure of the similarity of each FBG’s normalised Bragg wavelength, quantifying the precision of the plotted ANBW value. In these experiments, these values should be in close agreement given the absence of major temperature induced effects and the axial isotropy of strain. This is shown in both

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, where the bounding standard error lines closely follow and approximate the plotted ANBW value, showing that the ANBW is a high-precision representation of the overall shift in Bragg wavelength of each FBG along a chord. Moreover, the light blue lines do not represent an inter-trial average of each chord’s normalised Bragg wavelength shift. This is because in each trial, the time between the start of data collection, and the start of air injection, as well as the volume and frequency of each bubble produced, was different. This prevented a like-for-like comparison of each data point, disallowing an inter-trial averaging of results from being representative of the observations from any trial.

This high precision was also present in trials 2 and 3. In the air–water tests, the maximum standard error in the ANBW values recorded was never above ±3.23 × and ±2.96 × , respectively. Similarly, from the air–oil experiments’ trials 2 and 3, the maximum standard error of any ANBW measurement never increased above ±4.22 × and ±4.35 × , respectively. This supports the evaluation that the ANBW measurements produced using the developed FBG grid sensor are precise and reliable.

However, it is shown in chords 2–6 of

Figure 6 that, following the activation of air injection, the ANBW’s error values begin to slightly increase. Additionally, in

Figure 6’s region C, after the bubbles reach the FBG grid, the standard error lines (and thus also the standard deviation) also begin to diverge more from the average, but this increase in standard error gradually reduces before the next bubble reaches the sensor. This standard error line divergence and convergence process, about the ANBW, is not present in the air–water experiments typified by

Figure 5. Therefore, this could be a result of the more viscous nature of oil acting on the fibre chords, or a thermo-optic effect from a possible greater difference in phase temperatures. This latter option would produce different Bragg wavelength shifts from different FBGs along a chord. However, given that the increase in standard error, that begins before the bubbles reach the FBG grid, only occurs in the air–oil test, and given the use of polyimide-coated optical fibres (with small thermal expansion coefficients [

32,

33,

34]), it suggests that thermo-optic effects are less likely to be the cause, leaving this observation without satisfactory explanation.

The ability to have multiple sensing points along an optical fibre chord is a major advantage of FBG grid sensors. This is because, provided that cross-sensitivity effects are accounted for through experiment design or data analysis, each FBG along a given chord of an FBG grid should independently produce the same measurement in response to a strain along the chord, enabling reliable uncertainty quantification through comparison and statistical analysis of the distribution of these values. In these experiments, because of the use of polyimide-coated optical fibres to reduce thermo-optic effects, and the near uniform temperature through the measurement cross-section, this approach to uncertainty quantification was used, providing high-accuracy measurements of the bubble-induced strain along the sensor’s optical fibres.

4.4. Bubble Detection Sensitivity

To quantify the sensitivity of this FBG grid, an analysis is undertaken to compare the number of air bubbles that passed through the sensor, to the number ANBW peaks recorded.

Table 1 and

Table 2 display this information for trial 1 of both the air–water and air–oil experiments, alongside estimates of the diameter and length of the bubbles passing through the FBG grid (based on measurements from the high-speed camera data). These measurements were calculated using the external pipe diameter as a reference, and using image analysis software to measure the dimensions of the rising bubbles with this scale. For both the diameter and length, three measurements were made between different points on the bubbles’ perimeters that represented these dimensions—which were then averaged, providing estimates of the bubbles’ diameter and length when they pass through the FBG grid. The quoted uncertainties in

Table 1 and

Table 2 are the standard error of the three measurement values used to calculate each dimension. The predicted time it takes for each bubble to reach the FBG grid was calculated by measuring its upwards velocity from the high-speed camera data, with the time of ANBW shift values being taken from the data shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6.

For the purposes of this analysis, a large air bubble or air slug is defined as a bubble with a maximum observed width greater than a third of the diameter of the test section. Comparing

Figure 5 and

Table 1 shows that only some bubbles that passed through the FBG grid sensor produced an ANBW shift. In this period, as well as the first five large air slugs (highlighted in yellow in

Table 1), nine other smaller bubbles passed through the sensor.

To understand the relationship between a bubble’s size and the observed shifts in ANBW, the factors effecting the net force of a rising bubble must be considered. The net force of a rising bubble is given by its buoyant force, minus the total effects of gravity, viscous resistance, the additional mass force, and the Basset force. This is shown in in Equation (

3), where

is the buoyant force (

N),

is force from gravity (

N),

is the viscous resistance (

N),

is the added mass force (

N), and

is the Basset force (

N) [

35].

For a bubble to rise in a liquid column, its buoyant force must be greater than the summation of all the forces opposing its motion. Therefore, as a bubble’s buoyant force is directly proportional to its volume, the greater a bubble’s volume, the greater the force it will impose on an FBG, eliciting a larger shift in the ANBW. When the first, and largest, air slug is predicted to reach the sensor (at 15.73 ± 0.01 s into data acquisition period),

Figure 5 shows a clear, multi-chord response beginning at 15.72 ± 0.01 s, across chords 3 to 7. As this first bubble has the biggest volume observed in this experiment, it was hypothesised that it would produce the greatest magnitude ANBW shift across the largest number of fibre chords. From this analysis, this effect is clearly shown in

Figure 5, where the first ANBW shift is larger than all other observed ANBW responses, supporting this interpretation of the interaction. Similarly, in the air–oil experiments, the first air bubble produced also has the greatest volume, and likewise produced the largest magnitude ANBW shift of the experiment. This effect is seen across the repeated trials 2 and 3 for both the air–water and air–oil experiments.

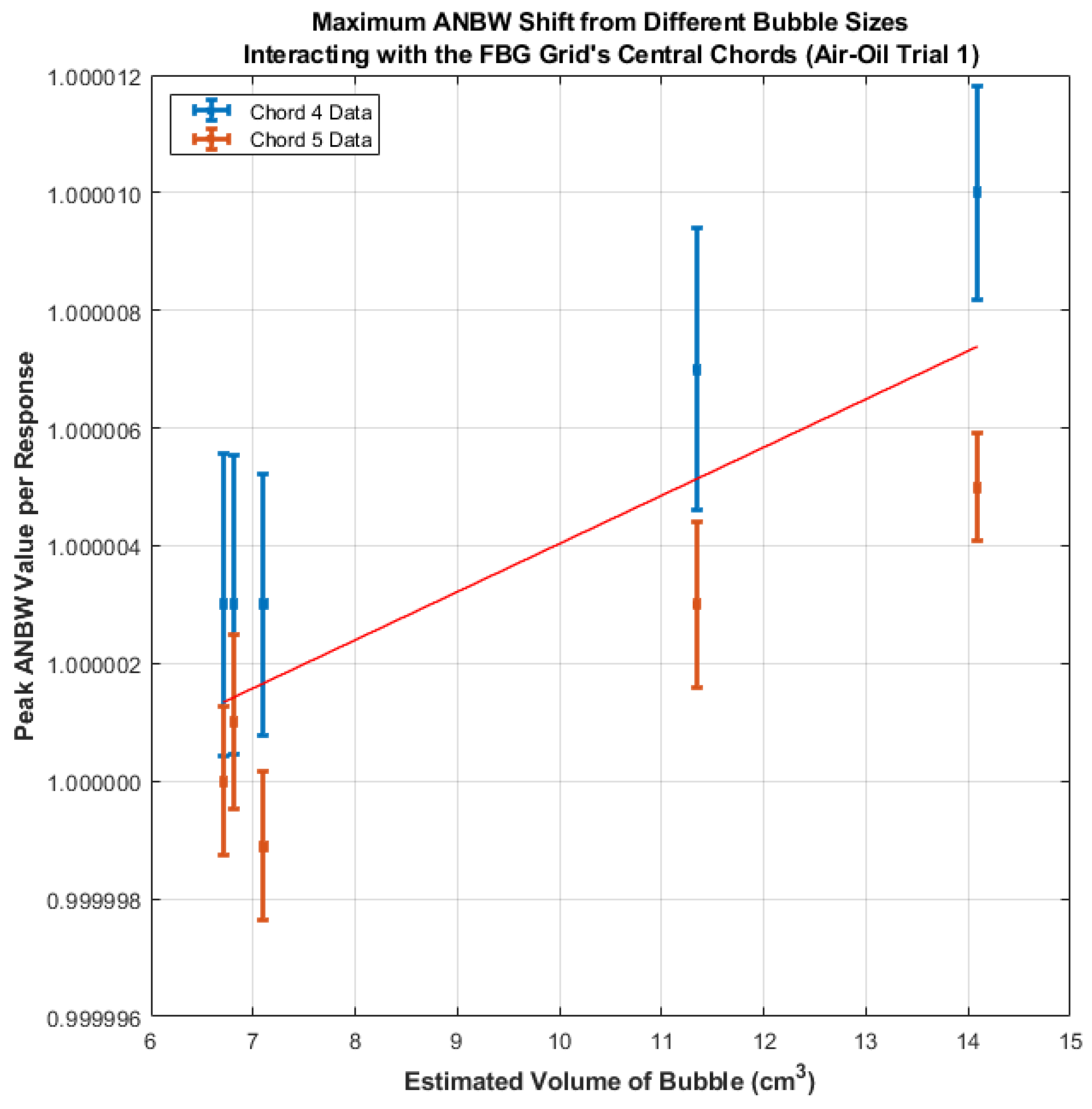

Furthermore, in the air–oil experiments, the size of the air bubbles was much more consistent, as shown in

Table 2, with no small trailing bubbles produced between the first five large air bubbles. All of these bubbles were similar in geometry, and rose in the centre of the test section. Additionally,

Table 2 also shows that the last three air bubbles had smaller volumes than the first two. Therefore, applying the previous logic, these bubbles would impart a smaller force on the FBG grid than the first two bubbles, meaning the magnitude of the associated ANBW shifts would be smaller. Chords 3–5 (and partially 2 and 6) of

Figure 6 display this pattern, with the maximum ANBW shift value corresponding to the first two bubbles being greater than the maximum ANBW shift associated with the last three bubbles.

Figure 9 further highlights this trend in the air–oil data, showing that the ANBW shift along the FBG grid’s central chords increases the larger the bubble volume interacting with the sensor. This reinforces the interpretation that it is the net force of a rising bubble that, upon interacting with an FBG grid in a standing liquid, imparts a measurable strain along the optical fibres that is proportional to the bubble’s volume. Given that the predicted times that the rising bubbles reach the FBG grid closely matches the start of each ANBW peak (no greater than a 0.02 s difference), combined with the more viscous oil minimising turbulence-induced strain, it can be deduced that the bubbles passing through the FBG grid are causing the ANBW peaks.

However, unlike the air–oil experiments, in the air–water trials, not every bubble passing through the FBG grid has corresponding ANBW peaks. This includes some of the large air bubbles highlighted in yellow. This has two possible explanations: firstly, for the smallest air bubbles with a diameter less than 6 mm, which is the inter-chord distance, it is likely that these bubbles can pass through, or be deflected by, the FBG grid without interacting with any optical fibres, meaning that they will not produce strain along the FBGs, leading to no measured ANBW shift. Secondly, as the magnitude of the ANBW should be proportional to the volume of the bubble, then even if a bubble does interact with an optical fibre, its volume could be insufficient to produce a net force that measurably strains the FBGs, leading to these bubbles also being undetected. This latter explanation can even extended to some of the larger bubbles observed in these trails, because after the first large air slug had been produced, the subsequent bubbles with a diameter sufficient to meet the chosen definition or a “large bubble” still have volumes less than their air–oil experiment counterparts. Therefore, it can be posited that ANBW shift is proportional to bubble volume. Future works, with apparatus capable of more control over bubble volume, should endeavour to further quantify the minimum bubble size that can be detected by an FBG grid. Yet, from these experiments, no bubble with a volume less than 2.140 ± 0.001 produced an ANBW peak.

Finally, in general, it should be noted that the predicted times that bubbles are expected to reach the FBG grid do not all exactly match (outside statistical uncertainty) the measured times of the ANBW shifts. It should be reiterated that these are estimates based on the measured velocity of each bubble from the high-speed camera data. Thus, in the unobserved 41.08 mm distance between bottom of the flange and the FBG grid, interactions may occur between bubbles, turbulence, and from the FBG grid itself that can change the velocity, and geometry, of a rising bubble, explaining the small discrepancies between expected interaction time and the measured times of ANBW shifts.

4.5. Bubble Dimensioning

In a 2015 paper by C. R. Zamarreño et al. [

10], it was reported that an 8 × 8 FBG grid could reproduce key dimensional properties of large air bubbles, including their general shape and size. This was achieved by analysing when FBGs on different fibre chords detected ANBW shifts and using the known spacing between chords to map the bubble surface. Using this approach, an attempt was made to analyse the data from the experiments in this work to infer the dimensions of the observed bubbles.

Consider again the first, and largest, air bubbles that pass through the FBG grid in both the air–water and air–oil experiments, these being bubble number 1 in both

Table 1 and

Table 2. To determine if the profile of the top of these bubbles can be reproduced, the time when each chord’s first ANBW peak began to increase is plotted against the chord’s positions in the sensing plane—as shown in

Figure 10. From this graph, it can be seen that, for the air–oil experiment, a parabolic profile, centred in the middle of the FBG grid, exists between the timings of the first ANBW responses across the sensor’s chords. This observation is in agreement with the shape of the leading edge of the bubble, as recorded in the high-speed camera data, and also conforms to the anticipated response expected from the results published by C. R. Zamarreño et al. [

9,

10,

27]. However, no such parabolic relationship is present in the response timings from the air–water experiment’s first bubble. Instead, a more sloped profile is seen, with chords 5–7 responding first, before chords 4, 3, and 2 sequentially. A possible explanation for this difference in response time profile could arise from the behaviour of bubbles in different viscosity liquids. In the air–oil experiments, the motion of the rising bubbles is much more regular and less erratic than the air–water tests. Therefore, in the region between the base of the flange and the sensor, when the bubble is unobserved by the high-speed camera, the bubble’s motion or shape could become perturbed, or be uncentred, leading to the slanted shape of the response time profile. Regrettably, validation of this proposed explanation is not possible without direct observation of the FBG grid as bubbles pass through it. This could not be achieved with the configuration of the LCIR; hence, further experiments will need to be conducted to analyse this proposed explanation.

Next, as only optical fibre chords that the bubbles interact with should experience an increase in strain, to measure the diameter of the bubbles passing through the sensor, the distance between the chords with FBGs that produced an ANBW peak is measured. This will only provide a coarse estimate of a bubble’s diameter, as this approach has a minimum resolution of 6mm. The results of this analysis technique are shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2 under the heading “Diameter from FBGs (mm)”. Despite accounting for the coarseness of measurement, comparing these values to the diameter measurements from the high-speed camera data reveals mixed results. In the air–water experiments, of the three air-bubbles that produced clear, multi-chord, ANBW peaks (bubbles 1, 8, and 12), the diameter measurements from the FBG grid only agrees with the camera diameter measurements for the last two large air bubbles. For these bubbles, their diameter was estimated to be 21.14 ± 0.50 mm and 23.85 ± 0.83 mm, respectively, using the high-speed camera data. Compared to 18.00 ± 3.00 mm and 24.00 ± 3.00 mm, respectively, from the FBG grid. Given the larger uncertainty range of the FBG grid measurements, it can be seen that both diameter measurement techniques produced values in statistical agreement. The same is also true for bubbles 4 and 5 in the air–oil trial, see

Table 2. However, for the first bubble in the air–water experiment, and the first three bubbles in the air–oil experiments, the FBG grid produced statistically meaningful underestimates of the bubble diameters. These underestimates are approximately 8-16mm less than the values estimated from the high-speed camera data. A possible explanation for this inaccuracy is that the outer edges of these bubbles deformed when the top of the bubbles reached the FBG grid, changing it dimensions from when it was observed. Regardless of its cause, the absence of visual access to the FBG grid prevents confirmation of either explanation, and therefore will be explored in future work.

In summary, despite occasional success in these experiments, this approach to estimating bubble dimensions is unreliable, with limited accuracy achieved in measuring the diameter of the observed bubbles. Hence, in a standing liquid, unlike the results reported by C. R. Zamarreño et al. in flowing liquids [

9,

10], the FBG grid investigated cannot reproduce accurate 3D models of large air bubbles. Nonetheless, in the air–oil tests, some dimensional properties where inferred, such as the hemispherical shape of the top of a bubble, using the timings of strain increase on each chord. This is in contrast with previous techniques that relay on strain decreases in two-phase flow.