1. Introduction

On 5 July 2021, higher than predicted measurements were reported for hydrogen equivalent concentrations, [Heq], obtained from a CANDU surveillance tube, B6S13 [

1]; [Heq] is equal to the mass of protium plus half of the mass of deuterium as ppm by mass of Zr. Concentrations were reported above 200 ppm, which is above the current license limit of 120 ppm [

1]. On 8 July 2021, similar high [Heq] values in another pressure tube, B3F16, from an outage inspection campaign were reported [

1]. Hydrogen isotopes in Zr-2.5Nb pressure tubes lower fracture toughness and can lead to failure by delayed hydride cracking [

2]. Both reactors were shut down at the time so there were no safety concerns.

These high concentrations were found within the rolled joints and slightly inboard from the contact regions (

Figure 1) between the stainless-steel end fittings and the pressure tube. The end of the rolled region is distinguished by a burnish mark situated 70 mm from the ends of the pressure tubes. High concentrations were observed in rolled joints up to the burnish marks and 10–70 mm inboard of the burnish marks, or 80–140 mm from the ends of the pressure tubes. High concentrations were mostly observed at the tops of the horizontal pressure tubes, from about 11 to 1 o’clock (

Figure 1). Flaw extension by delayed hydride cracking (DHC) requires a stress-rising flaw under tension. Such flaws exist occasionally at the bottoms of pressure tubes in the region of the rolled joints because of fretting with the fuel bundles that rest on bearing pads that centre the bundles in the pressure tubes and from scratching of the pressure tubes due to cross flow when bundles are inserted into the tubes during operation. No flaws have been observed in the region of high [Heq] at the tops of tubes. Thus, the risk of failure of the pressure tubes at the rolled joints is deemed to be small, given what is currently known about ingress of hydrogen isotopes and their effects in zirconium alloys. Failure of a pressure tube is a design-basis accident that is mediated by defence-in-depth, including leak-before-break [

3], to ensure safe shutdown to protect the public and environment.

These high Heq concentrations were well above predictions made with industry hydrogen-isotope ingress models. The measured tubes were some of the oldest with service lives of about 30 y. Models were validated with measurements from younger tubes; thus, the model predictions were mostly extrapolations in time. The models include empirical curve-fitted equations when physically based equations are not available, so the confidence in extrapolations is low. These models have produced adequate predictions in the past. The discrepancy with the observed high concentrations and the predictions of industry models seems too great to be explained by low-confidence extrapolations of curve fits. The status of deliberations with the regulator as of October 2023 can be found in [

5].

A diffusion model based on laboratory experiments provided good predictions of hydrogen concentrations at rolled joints up to about 28 years of operation using the Law of Times. (From the argument of the complementary error function in the diffusion equation, for the same temperature, two points,

x1 and

x2, will have the same concentration if x

1/√t

1 = x

2√t

2, where

t is time as described in [

6].) The model predictions were not good for times longer than 30 years. The concern is that a new ingress mechanism, not in the current lexicon, might be at play for tubes with service lives of about 30 y.

This paper will analyze publicly available data that suggest two independent but intertwined conclusions. First, excess ingress at 12 o’clock happens for long-lived tubes when tube sag opens a crevice between the rolled joint and the end fitting that provides an ingress route of deuterium from the annulus gas to the pressure tube. Pressure tubes are surrounded by insulating annulus gas that flows in the space between the pressure tubes, which reach up to 300 °C during operation, and co-axial calandria tubes that thermally separate pressure tubes from the moderator at 70 °C. This ‘sag-crevice’ theory will be related to the ‘cold-spot’ theory that posits a cold spot develops because of creep and mechanical contact of the pressure tube with the end fitting at 12 o’clock beyond the burnish mark, and high concentrations can be attributed to the resulting temperature gradient; hydrogen isotopes migrate to cooler regions in the pressure tubes by the Soret effect [

7].

The second conclusion of this paper will arise from the observation that mixtures of hydride from protium and deuteride precipitates are seen from the ends of some pressure tubes up to the burnish mark early in life but are only found past the burnish mark for long-lived tubes.

The data analyzed in this paper were presented in public meetings and are found on the public website of the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission as cited.

2. Interpretation of Rolled Joint Concentration Data

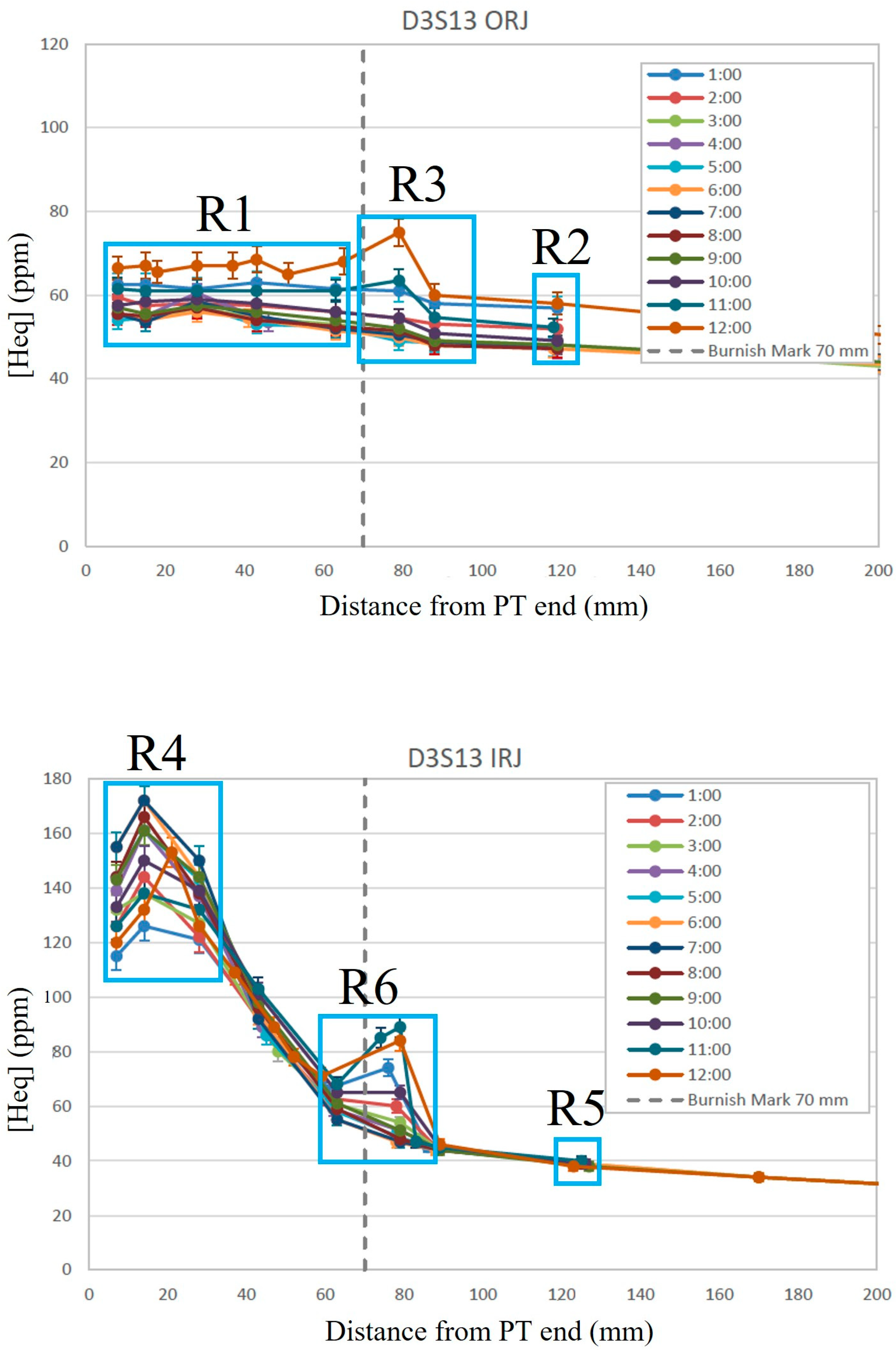

Consider the measured axial concentration profiles shown in

Figure 2 for the inlet and outlet rolled joint regions (IRJ and ORJ, respectively) for a tube in Darlington reactor, D3S13, after 25 years operating at full power (i.e., 25 Effective Full Power Years) [

8]. Overlaid on these profiles are six rectangles. Rectangle 1 (R1) shows concentrations at the ORJ stratified with the value at 6 o’clock on the bottom and 12 o’clock on the top, and 3 and 9 o’clock measurements between. This stratification is because the bottom temperature is higher than the top temperature because of flow bypass. The inside diameter of the tubes expands with time because irradiation, pressure and temperature induce creep. This diametral expansion is most evident at distances of about 1 m inboard from the outlet (i.e., 5 m from the inlet) where it reaches about 6% after 25 y. A consequence is that some coolant passes over the fuel bundles sitting on the pressure tube’s lower surface instead of going through the bundles where turbulent mixing results in a uniform temperature of the coolant. The result of diametral expansion is that the pressure tube at the outlet is slightly colder at 12 o’clock than at 6 o’clock. Hydrogen isotopes move to colder regions; thus, flow bypass causes stratification of concentrations of hydrogen isotopes in accord with a bottom–top temperature difference: i.e., the highest concentration is at the top where the temperature is lower. According to the stratification interpretation, even though the maximum flow bypass happens 1 m from the outlet, and the pressure tubes return to normal diameters before the outlet, and two more fuel bundles are in line before the rolled joint that will provide turbulent mixing, there remains a bottom–top temperature difference at the outlet, no doubt because of the fast coolant flow of 3 m/s.

The extent of the top–bottom concentration difference shown for various axial positions in R1 indicates that the bottom–top temperature difference does not vary significantly through the outlet rolled joint. A similar top–bottom concentration difference is seen at 120 mm in Rectangle 2 (R2). The implication is that the bottom–top temperature difference is the same for the data in R1 and R2. The overall concentrations in R2 are slightly lower than those in R1, likely because the temperature is slightly lower limiting thermally activated ingress.

The concentrations in Rectangle 3 (R3) spanning 80 mm also show a similar temperature dependence, but the magnitude of the concentration at 12 o’clock is higher than that seen in R1 and R2, with all other clock positions being similar to those seen in R1 and R2. It has been proposed that the 12 o’clock tube temperature in R3 is colder than that at 120 mm (R2) or within the rolled joint (R1) for axial distances less than or equal to 70 mm, perhaps because of contact from creep and sag of the pressure tube with the end fitting resulting in a cold spot. If 12 o’clock were colder, then the high concentration at 12 o’clock could be because of redistribution of hydrogen isotopes in accord with the colder temperature, but if true, then there should be some decrease in concentrations seen at other clock positions, in accord with the conservation of mass, but this is not seen. Concentrations at 11, 1, and 12 o’clock are seen to increase at 80 mm, whereas for clock positions at the bottom of the tube, concentrations interpolate well with concentrations on either side—there is no reduction of concentrations at the bottom that would be consistent with redistribution to the top of the tube because of a bottom–top temperature gradient. A precise value for the bottom–top temperature difference is not needed to conclude that a new ingress route is available late in life, although one will be calculated later; the need for a new route can be inferred from the top–bottom concentration difference in R3 being larger than the differences in R1 and R2, accompanied by the observation that concentrations for the bottom half of the tubes and nearest axial neighbors do not decrease in accord with the conservation of mass when the concentration at the top of the tubes increases.

A better explanation for the high concentrations in R3 is that ingress occurs late in life by a ‘new’ mechanism at about 80 mm, where ‘new’ means “not in the current ingress models”.

The data distinguished by Rectangles 4, 5, and 6 (R4, R5, R6) for the inlet rolled joint tell a different story. In R4, the concentrations vary substantively but with no stratification because there is no bottom–top temperature difference because there is no flow bypass—flow bypass can only affect the outlet. This substantial variation at about 20 mm does not survive to 120 mm as shown in R5 where the concentrations at different clock positions come together so that they overlap and are indistinguishable. The variation seen in R4 is likely caused by the variation in anoxic ‘reducing’ conditions expected circumferentially and along the length of the contact regions of rolled joints [

9]. In R4, the total concentrations are such that mixtures of hydrides and deuterides will be present up to the burnish mark.

In the diffusion model [

6] that successfully predicted the concentrations of deuterium diffusing inboard of the burnish mark, the initial steady-state boundary-value concentrations were all set equal to

C-, as shown in figure 5 in [

10]:

where

Co is the solvus concentration, i.e., terminal solid solubility,

V is the partial molar volume of hydrogen in solution,

σy is the matrix yield strength,

R is the gas constant and

T is the temperature in Kelvin. For diffusion from a region saturated in hydrides and deuterides, the hydrogen sink strength,

K, equals 2.9 [

10]. Hydrides and deuterides are present when equivalent hydrogen concentrations exceed

C- (28–37 ppm at the inlet and 51–64 ppm at the outlet) because stable hydrides can form within control volumes in which the concentration of hydrogen in solution adjacent to the hydride surface is at the solvus, and the concentration of hydrogen in solution at the periphery of the control volume is

C-; the ranges of

C- correspond to the range of temperatures seen at the inlets and outlets of reactors [

6].

The total concentrations in R4 at different clock positions vary significantly, but because the boundary-condition concentration, C-, at the burnish mark of hydrogen isotopes in solution is the same for all these data in R4 when hydrides and deuterides are present, there is a single diffusion profile emanating from the burnish mark. All diffusion inbound from the burnish mark results in the same axial profile emanating from the burnish mark, regardless of the variability of total concentrations at different clock positions in R4, so that past the burnish mark, the profiles at different clock positions overlap, which is most evident in R5. The 6 o’clock data in R6 seem to best follow the curvature interpolated between R4 and R5. The 12 o’clock concentrations in R6 do not follow the curvature interpolated between R4 and R5 in the same way that the 12 o’clock curvature in R3 does not follow the curvature interpolated between R1 and R2—something different is happening in R3 and R6.

R6 shows a concentration ‘blip’ at 80 mm from the tube inlet end that looks similar to the blip seen at the same location at the outlet. A blip is defined for locations that have unusually high concentrations compared with measured values on either side. The concentrations in the IRJ blip have the highest concentrations at, or near, 12 o’clock and the lowest concentrations at, or near, 6 o’clock, just like was seen for R3 for the ORJ. The similarity of the ORJ and IRJ blips suggests they are produced by the same mechanism late in life. The mechanisms for the blips could be because of simple thermal redistribution if a cold spot develops late in life, as was proposed for the ORJ. There is no corresponding concentration reduction at 6 o’clock or axially; hence, thermal redistribution is contrary to observations. Ingress from the annulus gas associated with pressure tube sag late in life is proposed to be the cause of high 12-o’clock concentrations in the blips at 80 mm in both the IRJ and ORJ as discussed later. Blips have not been reported for tubes with service lives less than about 25 years, although the reported data are scarce; see the few profiles in [

6].

3. Alternative Interpretation

There is another interpretation of the concentrations measured for these rolled joints that was developed while measurements were still incoming. Initially, it was conjectured that the stratification seen in the outlet blip in R3 was determined by the expected bottom–top temperature difference because of flow bypass. This conjecture led to a high value for the bottom–top temperature difference, between 20 and 30 °C [

11]. Thus, the outlet blip was initially explained.

Later, a large through-wall concentration gradient was found at the inlet burnish mark of tube B6S13: 400 ppm at the outside diameter (OD) of the pressure tube, and at the inside diameter (ID), the concentration was less than 50 ppm [

12]. Large through-wall concentration gradients were confirmed after examination of the D1U09 tube: the through-wall punch measurement Heq was 89 ppm, but Heq near the OD surface was over 250 ppm and near the ID surface it was below 50 ppm [

12].

These large concentration gradients presented a conundrum. If the top–bottom concentration difference seen in R3 (i.e., (76 (top)–49 (bottom)) ppm) produced a bottom–top temperature difference of 30 °C, then, by the same reasoning, the through-wall concentration difference would require an unrealistic 300 °C temperature drop across the 4 mm pressure tube at the inlet burnish mark.

The bottom–top temperature difference can be calculated if the top–bottom concentration difference is known via:

which is derived by equating to zero the hydrogen flux, written in terms of gradients of concentration, stress and temperature and when the drift current can be neglected because it is small [

13]. The equation for the hydrogen flux can be derived from the gradient of the chemical potential for hydrogen in solution. The concentration of hydrogen in solution in the flux equation is generalized to equal the total concentration, which includes hydrogen in hydride form, with the proposition in Einstein’s Brownian motion paper that ushered in the molecular kinetic theory of heat: suspended particles, such as pollen on a lake, or in our case hydrides, and solute molecules, or in our case solute hydrogen atoms, are identical in their behaviour differentiated

solely by their dimensions [

14]; see footnote 2 in [

13]. Thus, in Equation (2),

C is generalized to the total concentration;

Q* is the heat of transport. When the alternative interpretation was being developed, the only available value of

Q* was (25 ± 3) kJ/mol, determined from experiments where no hydrides were present [

13]. Hydrides were deemed irrelevant, even though in 1975 Maki and Sato had shown otherwise [

15], and observations attributed to hydrides were reported by others [

16,

17,

18]. Recently, a value for

Q* has been determined from experiments where hydrides were present: (116 ± 17) kJ/mol [

13].

Hydrides are present in the plots of

Figure 2. Using the top–bottom concentrations in R2 and Equation (2), the bottom–top temperature difference is (4.5 ± 2) °C. This value agrees with bottom–top differences determined from niobium diffusion during the decomposition of the beta phase in Zr-2.5Nb pressure tubes, about 5 to 10 °C [

19], and with thermohydraulic estimations of less than 5 °C by Greening [

20]. It seems much more reasonable to be able to maintain a 4.5 °C bottom–top difference than 20–30 °C given that along the 6 m length of the tube through the core the temperature rises 50 °C.

The value of Q* in the presence of hydrides provides a reasonable through-wall temperature gradient associated with a through-wall concentration gradient at the inlet burnish mark; recall, the concentration was 400 ppm at the OD of the pressure tube, and at the ID the concentration was less than 50 ppm for tube B6S13. To maintain this concentration difference requires a temperature difference of 30 to 90 °C when calculated with Equation (2) and the value of Q* in the presence of hydrides. If instead, Q* in the absence of hydrides is used, then the temperature difference across the 4 mm pressure tube width would be 140 to 420 °C. This latter range of temperature differences is deemed too large to maintain given that along the 6 m length of the tube the temperature rises 50 °C. Although temperature differences of 30 to 90 °C are high, differences of 140 to 420 °C seem unrealistically high. Thus, the value of Q* determined in the presence of hydrides seems to provide more realistic temperature gradients and solves the conundrum of the large concentration gradient at the inlet burnish mark.

Later when a blip was seen at the inlet, a different theory was developed for the inlet rolled joint blips when compared with the theory used to describe the outlet rolled joint elevated Heq blips—the outlet blip was already explained because of bottom–top temperature differences, albeit prematurely. The inlet blip was assumed to be caused by a cold spot at 80 mm and 12 o’clock that happened late in life because of pressure tube elongation over time due to creep [

12,

21]. It was suggested that this elongation, coupled with sag, could push the tops of the end fittings to rotate away from the core in a manner that would create mechanical contact of the pressure tube with the end fitting at 12 o’clock and about 80 mm. These mechanisms for both the inlet and outlet assume no new ingress routes and that the stratification was simple redistribution because of temperature gradients of hydrogen isotopes that were already present. This rotation mechanism is difficult to see given that the end fittings travel on bearings that accommodate thermal contraction and expansion of pressure tubes during shutdown and startup of the reactors. Not that this rotation cannot happen, but the end fittings are massive compared with pressure tubes, and they are tied into the ends of the reactor, and they rest on bearing, and the pressure tubes are already sagging (i.e., buckling), so it is difficult to see how a creeping tube can rotate an end fitting. It would seem easier for end fittings to move along the bearing travel than rotate and for the pressure tubes to buckle (i.e., sag) rather than rotate the massive end fitting.

If end-fitting rotation is happening and cold spots are produced when the pressure tube contacts the end fitting at 80 mm, see

Figure 1, then this rotation should happen at inlets and outlets, and blips should not be seen at 120 mm because this distance is well beyond the distance the end fittings penetrate the core, so no amount of rotation could result in contact at 120 mm; 100 mm is about the limit—see the distances shown in

Figure 1.

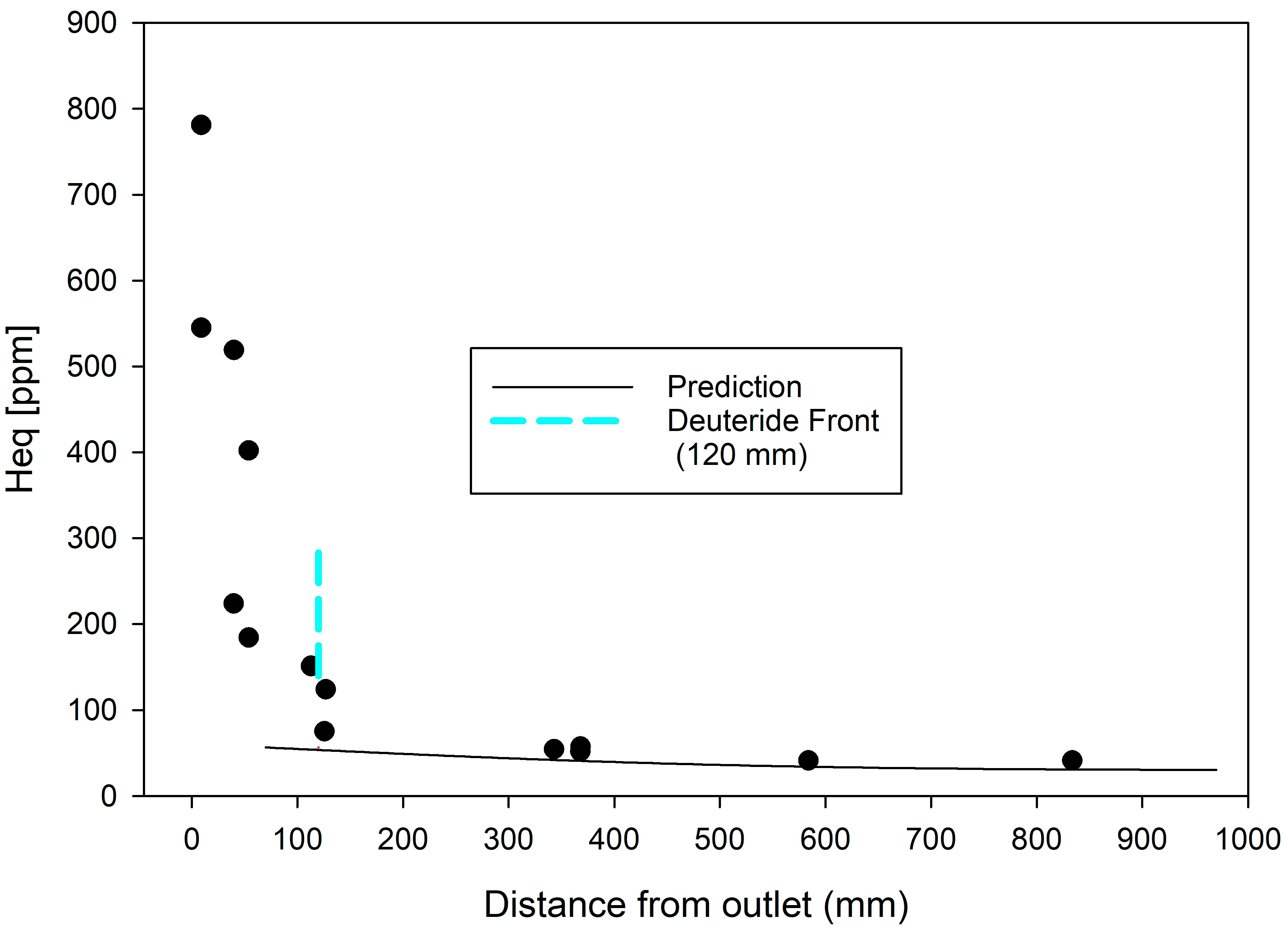

Figure 3 shows an apparent outlet blip at about 100 mm and maybe up to 120 mm, which might better be called the deuteride front. There could be creep-induced cold spots, but they cannot explain apparent blips at 120 mm, and they are not required to understand the current measurements.

4. Life-Limitations for the Pressure Tube at the Rolled Joint

Permeation from the end fittings is the main reason why high concentrations of hydrogen isotopes are seen at rolled joints early in life [

9]. These high concentrations have been seen for decades, but now they ‘suddenly’ have exceeded regulatory limits, so the industry and the regulator are questioning how long the rolled joints will last. Initially, it was hoped that there was no new ingress mechanism and that the blips and moving deuteride fronts could be explained by thermal redistribution of hydrogen isotopes that were already present. This seems unlikely now based on the arguments presented in this paper.

There are two reasons for concern.

First, blips are seen at 80 mm from the ends of the pressure tubes. These blips have been related previously [

23] to ingress from the annulus gas that happens because of the combination of sag pulling the tube away from the end fitting, creating a crevice at 12 o’clock, and reducing conditions that do not allow repair of the thin pressure-tube oxides that diffuse into the metal from the bottoms of cracks and pores in the crevice. This combined mechanism provides an ingress window to the tops of pressure tubes late in life. This combined mechanism has not been verified at 12 o’clock at 80 mm from the ends of the tubes, but ingress from the annulus was the mechanism proposed for the failure of tube P3L09 when sufficient oxidizing conditions in the gas were not maintained [

24]. Ingress via the annulus gas should be stopped with the judicious periodic addition of small amounts of oxygen to the annulus gas to eliminate the reducing conditions and repair the oxide closing the window. Delayed hydride cracking under reducing conditions stops when small amounts of oxygen are added [

25]. Most CANDU reactors now maintain 0.5–5.0 vol% oxygen in the annulus gas system to ensure any hydrogen or deuterium gas that enters the annulus gas system is recombined to form water and to provide further insurance that the protective surface oxide on the outside of the pressure tube is maintained. However, the narrow ‘pigtail’ tubes that replenish the annulus gas can be blocked, and chemistry conditions inside crevices are notoriously difficult to predict.

The second concern is that a deuteride front is seen to extend inboard of the burnish mark; see

Figure 3 where there are deuterides up to 120 mm, well beyond the burnish mark at 70 mm. Prior to these recent measurements, deuterides were seen only up to the burnish mark, and all hydrogen past the burnish mark was in solution. It was generally believed that the concentration of hydrogen could not exceed the terminal solid solubility (TSS) limit [

26,

27]. Many current ingress models include in the formalism a rate equation, for example [

28,

29], where

where

C is the concentration of hydrogen in solution because this concentration cannot exceed the TSS limit. The TSS concentration is defined differently depending on whether hydrides and deuterides are dissolving, precipitating, growing or nucleating, which is in violation of Gibbs Phase Rule that says only one TSS can exist [

30], as explained in [

31]. Rate equations of this form are not representative of observations. There is no indication that ingress stops, or even slows down, or in any way notices the solubility limit [

32]. Models that are limited by solubility limits would underpredict rolled joint concentrations when concentrations approach the solubility limit late in life.

The concentration of hydrogen in solid solution will increase to the solubility limit as expected from Equation (3), but the total concentration will not be so limited.

Figure 3 shows concentrations for locations greater than about 200 mm are all about the same: the profile is becoming ‘horizontal’ as the concentrations are approaching

C-, not the solubility limit [

10]. Stable hydrides form within a control volume that has the concentration of hydrogen in solution equal to the solvus in the region adjacent to the hydride and the concentration of hydrogen in solution equal to

C- at the extent of the control volume. As the concentration of hydrogen in solution in the bulk reaches

C-, small positive concentration perturbations can readily make stable hydrides because the steady-state boundary- condition concentration at the extent of any control volume that forms is already present in the bulk. Therefore, as equivalent hydrogen concentrations in solution rise to

C- in the bulk, there will be an increasing propensity to form stable hydrides. Forming stable hydrides past the burnish mark is expected when the concentration ingress profile becomes ‘horizontal’, as shown in

Figure 3. The appearance of deuterides ‘suddenly’ forming late in life past the burnish mark is not a sign of a new ingress route or mechanism; compare with the blips that indicate a new mechanism to satisfy mass balance. Instead, deuterides forming past the burnish mark is a consequence of reaching

C- in the bulk, which only happens late in life. Unfortunately, because this deuteride formation is a natural process, there is very little that can be done to mitigate the risks deuterides bring, such as lower fracture toughness and DHC. The solution is to lower concentrations in the rolled joint [

23].

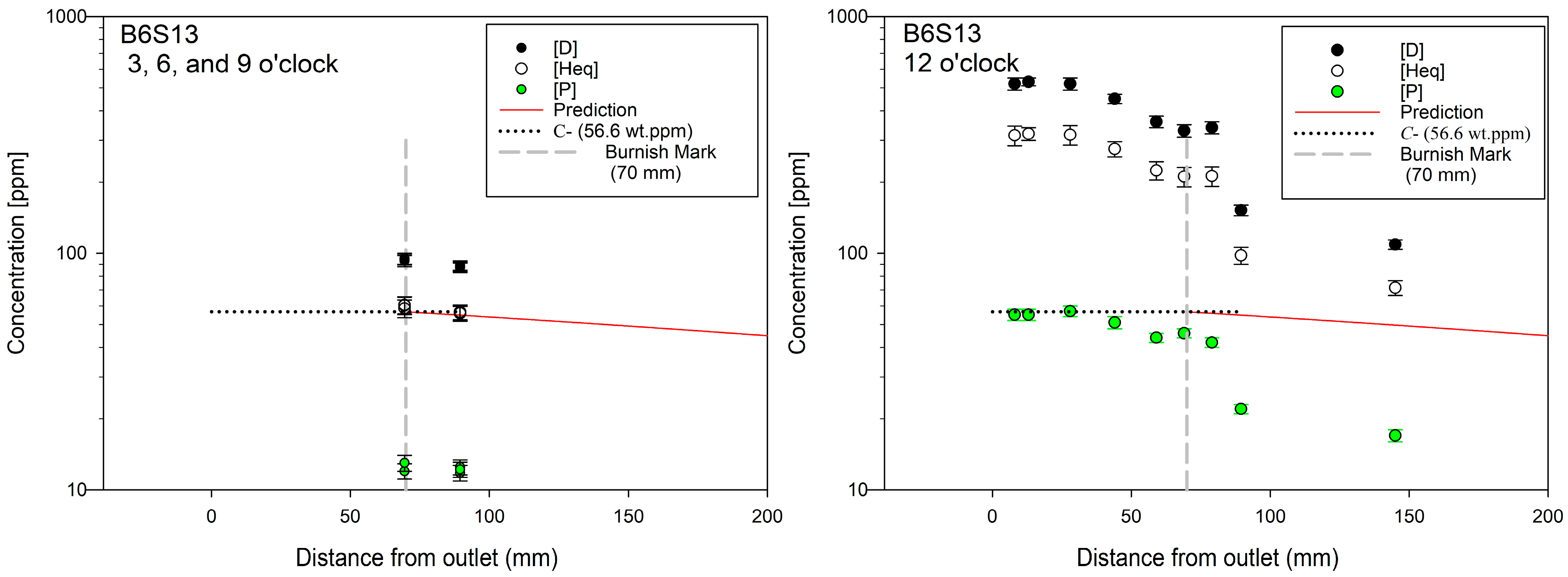

Figure 4 shows ingress profiles determined from through-wall punches of pressure tube B6S13 removed after 28 y as part of a surveillance campaign [

22]. In the plot on the left of

Figure 4, the circular markers at 69 and 89.5 mm are six overlaid deuterium, Heq and protium concentrations, i.e., six data points, determined for 3, 9 and 6 o’clock. These Heq concentrations match well with diffusion model predictions (i.e., solid red curve) calculated assuming hydrides/deuterides formed within the first six months in the rolled joint region of the pressure tube [

6]. The steady-state boundary-value concentration is

C- (i.e., 56.5 ppm for this tube) for these 3, 9 and 6 o’clock positions. This diffusion model was determined from laboratory-scale (i.e., 7 cm) rolled-joint analogues and, when scaled using the law of times, has been shown to predict full-scale rolled joint ingress profiles to within observed measurement error without modification. Concentrations at 12 o’clock are considerably higher than the values at 3, 9 and 6 o’clock as shown in the plot on the right in

Figure 4. As previously inferred, there is ingress late in life at 12 o’clock that is not happening at 3, 9, and 6 o’clock. ‘Late-in-life’ is inferred because hydrogen isotopes have moved axially inbound past the burnish mark, 10–75 mm from the burnish mark, but there has been insufficient time to move as much deuterium circumferentially 81 mm from 12 o’clock to 3 and 9 o’clock positions: at the burnish mark, deuterium concentrations are 330 ppm at 12 o’clock, but only 94 ppm at 3 and 9 o’clock. Ingress in B6S13 at 12 o’clock is happening along the entire length of the rolled joint and into the pressure tube beyond the burnish mark as is also seen in

Figure 3 for B3F16.

5. Isotope Effects

There remain several locations in and around the rolled joints where the concentrations of protium and deuterium so far reported have values that are suggestive of more exotic behaviour. These results are mentioned here along with speculation on what might cause them to stimulate further discussion should similar results be found in the future.

Protium concentrations at 12 o’clock in

Figure 4 are roughly equal to

C- up to, and maybe a little after, the burnish mark, after which they decline in a manner reminiscent of simple diffusion from a hydride/deuteride front, as shown in figure 5 in [

10]. Deuterium concentrations also change in a similar way. Protium and deuterium concentrations at 12 o’clock are correlated (Pearson Correlation Coefficient is

p = 0.98).

An implication of this correlation is that protium and deuterium are diffusing in lockstep when hydrides and deuterides are present. When protium and deuterium diffuse independently, one in the absence of the other, the diffusivity of deuterium is 1/√2 times slower than that of protium because of the difference of the masses. When hydrides and deuterides are present, the equivalent hydrogen concentration in solution equals the solvus, so protium and deuterium concentrations in solution are not independent, and their concentrations are constrained to sum to the solvus value. This dependence means protium and deuterium diffuse in lockstep when hydrides or deuterides are present, and there is no isotope effect.

The inference is more than deuterium and protium in solution diffusing at the same rate; in addition, protium and deuterium as deuteride diffuse in lockstep because deuterides are clearly present at these concentrations of total deuterium. The current observations might be described as ostensible deuteride diffusion limited by a common diffusivity of equivalent hydrogen isotopes in solution.

When deuterides ostensibly diffuse they effectively carry with them roughly five times more atoms than protium atoms do when they diffuse in solution. In

Figure 4, protium concentrations are about five times lower than corresponding equivalent hydrogen concentrations that are high enough to ensure deuterides. A similar carrying capacity was observed for ostensible hydride diffusion across temperature gradients [

13].

The flux of hydrogen isotopes, J, can be written as follows:

D is diffusivity,

σ is the hydrostatic stress,

C is the total concentration of hydrogen, in accord with Einstein’s proposition,

R is the gas constant,

T is the temperature in Kelvin and

x is the axial distance along the pressure tube. The first term in the bracket in Equation (4) is constant and negative because of the correlation between the various isotope concentrations and the observation that lines in

Figure 4 connecting adjacent concentrations for protium and deuterium at different distances are ‘parallel’, with a negative slope. The hydrostatic stress changes with temperature, but temperature does not vary significantly over these distances from the rolled joints, so the second term in the bracket in Equation (4) is neglected for this discussion. Thus, the flux is proportional to the product of thediffusivity and concentration, and Equation (4) becomes

When hydride and deuteride precipitates form, the diffusivity of hydrogen and deuterium in solution is lowered because the equivalent concentration of hydrogen isotopes in solution is constrained to sum to the solubility limit in solid solution, CTSS. Thus, D is lowered when precipitates form. For the flux to remain the same, C needs to rise to offset the lowering of D caused by precipitation.

For many pressure tubes, [Heq] in the rolled joint, i.e., up to the burnish mark, is well above

C- early in life [

6]. The implication is that diffusivity is low in the rolled joints of these tubes. For these tubes, the axial [Heq] profiles beyond the burnish marks are all below

C-, and there are no precipitates, so the diffusivity of deuterium in solution limits ingress past the burnish mark for early tubes, as can be seen in [

6]. [Heq] accumulates in the rolled joints when it cannot disperse rapidly axially because of the reduced diffusivity up to the burnish mark. With time, the concentration rises in the rolled joint until it offsets the lowered diffusivity in the presence of precipitates; at this point, the fluxes on either side of the burnish mark match, and steady-state inbound ingress occurs.

The factor of five for the ratio of equivalent hydrogen concentrations to corresponding protium concentrations in

Figure 4 for B6S13 suggests that the diffusivity of protium will decrease by a factor of five in the presence of precipitates. In B3F16 the ratio is closer to six. Thus, we predict the diffusivity of protium in the presence of precipitates will be five to six times lower than the diffusivity observed for protium in the absence of precipitates (i.e., 1/√2(1 − 1/√2)). The diffusivity of deuterium should be reduced by a factor of roughly 0.3 in the presence of precipitates (i.e., (1 − 1/√2)).

Hydrogen isotopes accumulate to high concentrations within the pressure tube of the rolled joint up to the burnish mark, but with time and only late in life do these high concentrations move past the burnish mark and down the tube. The delay before steady-state diffusion inboard of the burnish mark occurs might be related to the ‘sudden’ appearance of precipitates beyond the burnish marks late in life. This delay might also be related to unstable oscillating precipitates, striations, and the delay in delayed hydride cracking.

A surprising result is that protium is found in tube B6S13 after 28 y operating in a heavy water reactor; see the lower circular markers in

Figure 4. It was expected that after such a long service time, any protium would be well dispersed and certainly not concentrated in the compressed region of the rolled joints at concentrations (≈55 ppm) that are well above the initial as-received value of about 12 ppm for tubes of this era. It is even more surprising that the protium concentrations at 12 o’clock in the rolled joint are similar to

C- (≈57 ppm) and appear to have an axial profile beyond the burnish mark in lockstep with ostensible deuteride diffusion; at other clock positions, protium concentrations are equal to the as-received value. Understanding why protium collects in the rolled joints after 28 y will likely not be an important feature of any model that could be used to predict future fitness-for-service, but it would provide a sense of confidence should such an understanding be forthcoming, perhaps using concepts such as zero-point energy and zone refining. Perhaps the higher-than-expected protium seen at the rolled joints is related to the preference for protium over deuterium (i.e., up to 9 times) found in corrosion experiments [

33] and electrochemical and permeation experiments [

34].

6. Conclusions

This paper considered publicly available measurements of ingress of hydrogen isotopes into rolled joints of zirconium alloy pressure tubes in CANDU reactors after decades of service that suggested two independent but intertwined mechanisms:

First, a route for ingress is proposed. Excess ingress at 12 o’clock happens for long-lived tubes when tube sag opens a crevice between the rolled joint and the end fitting that provides an ingress route for deuterium from the annulus gas to the pressure tube. This ‘sag-crevice’ theory was related to the ‘cold-spot’ theory that posits a cold spot develops because of creep and mechanical contact of the pressure tube with the end fitting at 12 o’clock, and high concentrations were attributed to the resulting temperature gradient; hydrogen isotopes migrate to cooler regions in the pressure tubes. The sag-crevice theory was preferred over the cold-spot theory because blips at 80 mm showed increased concentrations at 12 o’clock, but no corresponding reductions in concentrations at other clock positions and axial positions that would happen because of conservation of mass if thermal redistribution occurred.

Second, a new mechanism for deuterides past the burnish mark is proposed. The second conclusion of this paper addresses the observation that mixtures of hydride and deuteride precipitates are seen from the ends of some pressure tubes up to the burnish mark early in life but are only found, sometimes suddenly, past the burnish mark for long-lived tubes, after about 30 y. Deuterides forming past the burnish mark are a consequence of reaching C- in the bulk past the burnish mark, i.e., the ingress profiles approach the horizontal, which only happens late in life.