A Suggested One-On-One Method Providing Personalized Online Support for Females Clarifying Their Fertility Values

Abstract

1. Introduction

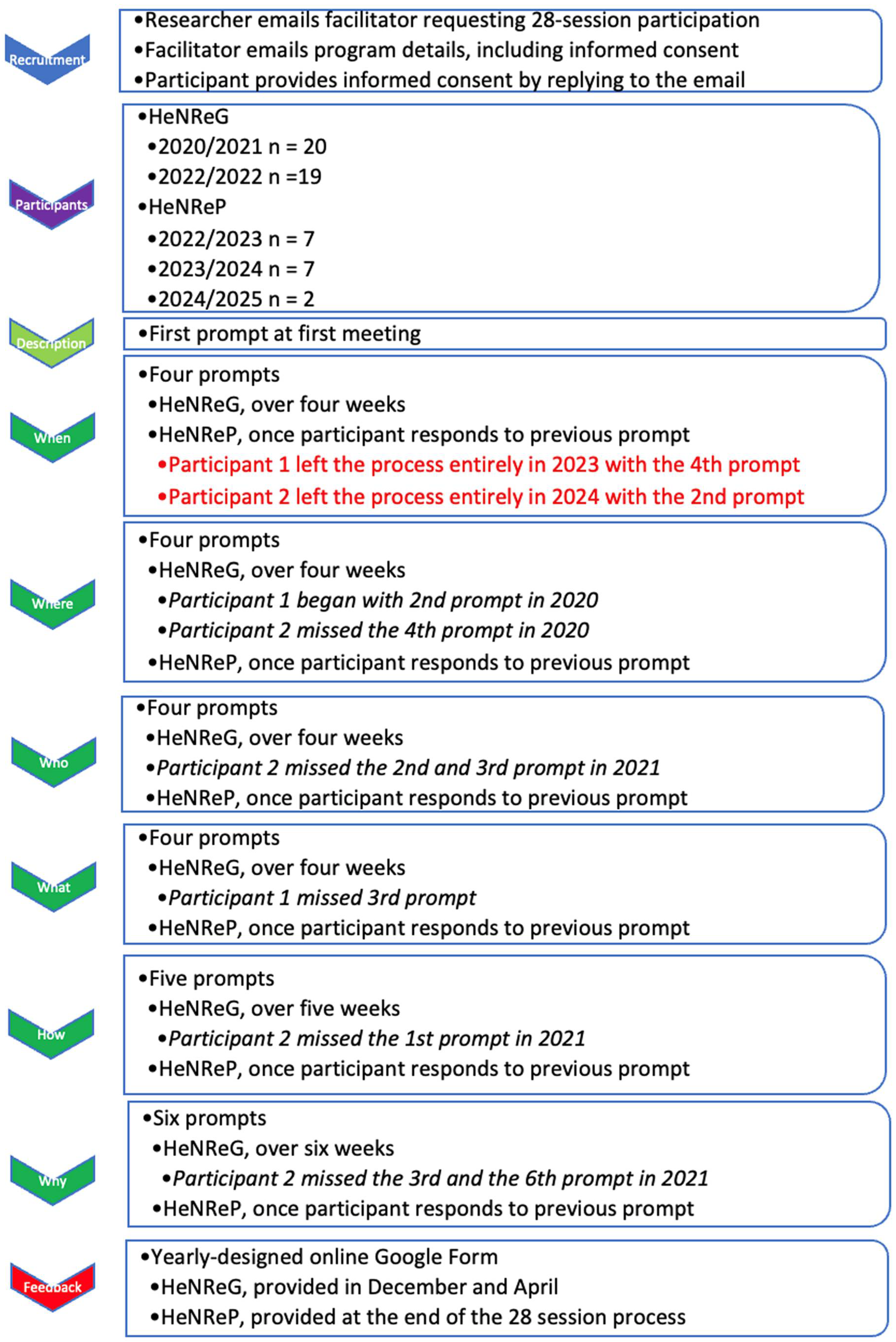

2. Results

3. Discussion

Limitations and Suggested Future Research Directions

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Order | First Word | Body of Question |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Describe | yourself regarding your fertility choices |

| 2 | When | have you thought about your fertility |

| 3 | When | did you consider whether you could become pregnant |

| 4 | When | did you idealize the male who might impregnate you |

| 5 | When | have you worried about the possibility of pregnancy |

| 6 | Where | could you ask for help in making fertility choices |

| 7 | Where | do you locate the most trusted fertility information |

| 8 | Where | is the healthcare provider you confide in with fertility choices |

| 9 | Where | would you go online to find fertility information |

| 10 | Who | has engaged you in talking about fertility choices |

| 11 | Who | would support your fertility choices |

| 12 | Who | would you trust with your fertility choices |

| 13 | Who | has given you valuable information regarding fertility choices |

| 14 | What | would you do if you became pregnant |

| 15 | What | conditions would make you want to be pregnant |

| 16 | What | support would you expect from the father if you were pregnant |

| 17 | What | would happen if you couldn’t realize your fertility choices |

| 18 | How | would you reorganize commitments if you became pregnant |

| 19 | How | would your health matter if you became pregnant |

| 20 | How | much would the father know about your pregnancy |

| 21 | How | would you be sure you wanted to be pregnant |

| 22 | How | do you determine relevant information about pregnancy |

| 23 | Why | are you unsure this is the best time to get pregnant |

| 24 | Why | does climate change matter regarding fertility choices |

| 25 | Why | does pregnancy create tension between males and females |

| 26 | Why | is it relevant how you respond to a pregnancy |

| 27 | Why | should you notice the health-related concerns of pregnancy |

| 28 | Why | reconsider what you value in your fertility choices |

References

- Idris, I.B.; Hamis, A.A.; Bukhori, A.B.M.; Hoong, D.C.C.; Yusop, H.; Shaharuddin, M.A.-A.; Fauzi, N.A.F.A.; Kandayah, T. Women’s Autonomy in Healthcare Decision Making: A Systematic Review. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, K.; Galavotti, C.; Omoluabi, E.; Challa, S.; Waiswa, P.; Liu, J. Preference-Aligned Fertility Management as a Person-Centered Alternative to Contraceptive Use-Focused Measures. Stud. Fam. Plan. 2023, 54, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramya, S.; Poornima, P.; Jananisri, A.; Geofferina, I.P.; Bavyataa, V.; Divya, M.; Priyanga, P.; Vadivukarasi, J.; Sujitha, S.; Elamathi, S.; et al. Role of Hormones and the Potential Impact of Multiple Stresses on Infertility. Stresses 2023, 3, 454–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negris, O.; Lawson, A.; Brown, D.; Warren, C.; Galic, I.; Bozen, A.; Swanson, A.; Jain, T. Emotional Stress and Reproduction: What Do Fertility Patients Believe? J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2021, 38, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duane, M.; Stanford, J.B.; Porucznik, C.A.; Vigil, P. Fertility Awareness-Based Methods for Women’s Health and Family Planning. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 858977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, S.; Lamaro Haintz, G.; McKenzie, H.; Graham, M. Factors That Shape Women’s Reproductive Decision-Making: A Scoping Review. J. Res. Gend. Stud. 2021, 11, 9–31. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, R.; Alam, K.; Rahman, S.M.; Keramat, S.A.; Al-Hanawi, M.K. Women’s Empowerment and Fertility Decision-Making in 53 Low and Middle Resource Countries: A Pooled Analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, P.; Bailey, J.V.; Stephenson, J.; Oliver, S. Factors Influencing Contraception Choice and Use Globally: A Synthesis of Systematic Reviews. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2022, 27, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemzadeh, M.; Shariati, M.; Mohammad Nazari, A.; Keramat, A. Childbearing Intention and Its Associated Factors: A Systematic Review. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 2354–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikken, J.F.W.; Kowalik, C.R.; Emanuel, M.H.; Bongers, M.Y.; Spinder, T.; Jansen, F.W.; Mulders, A.G.M.G.J.; Padmehr, R.; Clark, T.J.; Van Vliet, H.A.; et al. Septum Resection versus Expectant Management in Women with a Septate Uterus: An International Multicentre Open-Label Randomized Controlled Trial. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 36, 1260–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abruzzese, G.A.; Silva, A.F.; Velazquez, M.E.; Ferrer, M.; Motta, A.B. Hyperandrogenism and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Effects in Pregnancy and Offspring Development. WIREs Mech. Dis. 2022, 14, e1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramraj, B.; Subramanian, V.M.; Vijayakrishnan, G. Study on Age of Menarche between Generations and the Factors Associated with It. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 11, 100758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Shen, W.; Zhang, J. The Life Cycle of the Ovary. In Ovarian Aging; Wang, S., Ed.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 7–33. ISBN 978-981-19-8847-9. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, R.J.; Liu, B. Conception and Pregnancy. In Fertility, Pregnancy, and Wellness; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 53–71. ISBN 978-0-12-818309-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kölle, S. Sperm-oviduct Interactions: Key Factors for Sperm Survival and Maintenance of Sperm Fertilizing Capacity. Andrology 2022, 10, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.Y.B.; Evans, R.; Mentzakis, E.; Cheong, Y. P-405 Assessing Women’s Preferences in a Novel Intrauterine Device Designed to Monitor the Womb Environment in Real Time: A Discrete Choice Experiment. Hum. Reprod. 2022, 37, deac107.382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, E.N.; Lundberg, T.R. Transgender Women in the Female Category of Sport: Perspectives on Testosterone Suppression and Performance Advantage. Sports Med. 2021, 51, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindqvist, A.; Sendén, M.G.; Renström, E.A. What Is Gender, Anyway: A Review of the Options for Operationalising Gender. Psychol. Sex. 2021, 12, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Doef, S. Can I Have Babies Too? Sexuality and Relationships Education for Children from Infancy up to Age 11; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-78775-500-0. [Google Scholar]

- Cacciatore, R.; Öhrmark, L.; Kontio, J.; Apter, D.; Ingman-Friberg, S.; Jokela, M.; Sajaniemi, N.; Korkman, J.; Kaltiala, R. What Do 3–6-Year-Old Children in Finland Know about Sexuality? A Child Interview Study in Early Education. Sex Educ. 2024, 24, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lonkhuijzen, R.M.; Garcia, F.K.; Wagemakers, A. The Stigma Surrounding Menstruation: Attitudes and Practices Regarding Menstruation and Sexual Activity During Menstruation. Women’s Reprod. Health 2023, 10, 364–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslowski, K.; Biswakarma, R.; Reiss, M.J.; Harper, J. Sex and Fertility Education in England: An Analysis of Biology Curricula and Students’ Experiences. J. Biol. Educ. 2024, 58, 702–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthfiyah, A.; Hayati, E.N. Understanding Premarital Sexual Behavior: A Qualitative Case Study among Male and Female College Students. J. Educ. Health Community Psychol. 2025, 14, 791–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeatman, S.; Sennott, C. Fertility Desires and Contraceptive Transition. Pop. Dev. Rev. 2024, 50, 511–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.; Yarger, J.; Sedlander, E.; Urbina, J.; Hopkins, K.; Rodriguez, M.I.; Fuentes, L.; Harper, C.C. Concern That Contraception Affects Future Fertility: How Common Is This Concern among Young People and Does It Stop Them from Using Contraception? Contracept. X 2023, 5, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnain, A.M.; Snopkowski, K. Maternal Investment in Arranged and Self-Choice Marriages: A Test of the Reproductive Compensation and Differential Allocation Hypothesis in Humans. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2024, 45, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, B.; Phillips, S.; Biswakarma, R.; Talaulikar, V.; Harper, J.C. Women’s Knowledge and Attitudes to the Menopause: A Comparison of Women over 40 Who Were in the Perimenopause, Post Menopause and Those Not in the Peri or Post Menopause. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, K.; Charles, A. Barriers to Accessing Effective Treatment and Support for Menopausal Symptoms: A Qualitative Study Capturing the Behaviours, Beliefs and Experiences of Key Stakeholders. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2023, 17, 2971–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tintelen, A.M.G.; Stulp, G. Explaining Uncertainty in Women’s Fertility Preferences. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakkerud, E. “There Are Many People Like Me, Who Feel They Want to Do Something Bigger”: An Exploratory Study of Choosing Not to Have Children Based on Environmental Concerns. Ecopsychology 2021, 13, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santulli, P.; Blockeel, C.; Bourdon, M.; Coticchio, G.; Campbell, A.; De Vos, M.; Macklon, K.T.; Pinborg, A.; Garcia-Velasco, J.A. Fertility Preservation in Women with Benign Gynaecological Conditions. Hum. Reprod. Open 2023, 2023, hoad012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aureliano, W. Difficult Decisions and Possible Choices: Rare Diseases, Genetic Inheritance and Reproduction of the Family. Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 363, 117380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bártolo, A.; Santos, I.M.; Monteiro, S. Toward an Understanding of the Factors Associated With Reproductive Concerns in Younger Female Cancer Patients: Evidence From the Literature. Cancer Nurs. 2021, 44, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, S.L.; Vaksdal, R.H.; Barra, M.; Gamlund, E.; Solberg, C.T. Abortion and Multifetal Pregnancy Reduction: An Ethical Comparison. Etikk Praksis Nord. J. Appl. Ethics 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Pandey, G. Understanding the Impact of Triazoles on Female Fertility and Embryo Development: Mechanisms and Implications. Toxicol. Rep. 2025, 14, 101948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, S.; Garzon, S.; Russo, A.; Ianniciello, C.Q.; Santi, L.; Laganà, A.S.; Raffaelli, R.; Franchi, M. Fertility and Reproductive Outcome after Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy: Comparison among Methotrexate, Surgery and Expectant Management. Arch. Gynecol. Obs. 2021, 303, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maqsood, Z.; Zafar, M.; Mazha, S.B.; Sultan, K. Community Acceptability of Contraception after Induced versus Spontaneous Miscarriage. Prof. Med. J. 2021, 29, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissmann, R.; Lokot, M.; Marston, C. Understanding the Lived Experience of Pregnancy and Birth for Survivors of Rape and Sexual Assault. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasaven, L.S.; Mitra, A.; Ostrysz, P.; Theodorou, E.; Murugesu, S.; Yazbek, J.; Bracewell-Milnes, T.; Ben Nagi, J.; Jones, B.P.; Saso, S. Exploring the Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceptions of Women of Reproductive Age towards Fertility and Elective Oocyte Cryopreservation for Age-Related Fertility Decline in the UK: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Hum. Reprod. 2023, 38, 2478–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidane, B.D.; Mekonnen, H.; Mekango, D.E.; Moges, S.; Ejajo, T. Fertility Desire and Associated Factors among People Living with HIV/AIDs Attending Anti-Retroviral Therapy Clinic in Wachemo University Negist Eleni Mohammed Memorial Teaching Hospital, Southern Ethiopia. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, I.C.; Gutierrez-Castellanos, N.; Lenschow, C.; Lima, S.Q. Ready or Not: Neural Mechanisms Regulating Female Sexual Behavior. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2025, 93, 103069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temmesen, C.G.; Faber Frandsen, T.; Svarre-Nielsen, H.; Petersen, K.B.; Clemensen, J.; Andersen, H.L.M. Women’s Reflections on Timing of Motherhood: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Evidence. Reprod. Health 2023, 20, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielawska-Batorowicz, E.; Zagaj, K.; Kossakowska, K. Reproductive Intentions Affected by Perceptions of Climate Change and Attitudes toward Death. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.V.; Koert, E.; Sylvest, R.; Maeda, E.; Moura-Ramos, M.; Hammarberg, K.; Harper, J. Fertility Education: Recommendations for Developing and Implementing Tools to Improve Fertility Literacy. Hum. Reprod. 2024, 39, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speizer, I.S.; Bremner, J.; Farid, S. Language and Measurement of Contraceptive Need and Making These Indicators More Meaningful for Measuring Fertility Intentions of Women and Girls. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2022, 10, e2100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, A.; Crocker, L.; Mathur, A.; Holman, D.; Weston, J.; Campbell, S.; Housten, A.; Bradford, A.; Agrawala, S.; Woodard, T.L. Patients’ and Providers’ Needs and Preferences When Considering Fertility Preservation Before Cancer Treatment: Decision-Making Needs Assessment. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 5, e25083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, B.; Shawe, J.; Stephenson, J. A Mixed Methods Study Investigating Sources of Fertility and Reproductive Health Information in the UK. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2023, 36, 100826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, C.; Wu, J.; Ye, Y.; Yang, N.; Pei, H.; Gao, H. How Media Use Influences the Fertility Intentions Among Chinese Women of Reproductive Age: A Perspective of Social Trust. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 882009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aassve, A.; Le Moglie, M.; Mencarini, L. Trust and Fertility in Uncertain Times. Popul. Stud. 2021, 75, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, K.; Brown, R.C.; Savulescu, J. Disclosure and Consent: Ensuring the Ethical Provision of Information Regarding Childbirth. J. Med. Ethics 2025, 51, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skvirsky, V.; Taubman-Ben-Ari, O.; Horowitz, E. Mothers’ Experience of Their Daughters’ Fertility Problems and Treatments. J. Fam. Psychol. 2022, 36, 1418–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinke-Allmang, A.; Bhatia, A.; Gorur, K.; Hassan, R.; Shipow, A.; Ogolla, C.; Keizer, K.; Cislaghi, B. The Role of Partners, Parents and Friends in Shaping Young Women’s Reproductive Choices in Peri-Urban Nairobi: A Qualitative Study. Reprod. Health 2023, 20, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnak, D.; Becker, S. Accuracy of Wives’ Proxy Reports of Husbands’ Fertility Preferences in Sub-Saharan Africa. DemRes 2022, 46, 503–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambasivam, I.; Jennifer, H.G. Understanding the Experiences of Helplessness, Fatigue and Coping Strategies among Women Seeking Treatment for Infertility—A Qualitative Study. J. Educ. Health Prom. 2023, 1, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chola, M.; Hlongwana, K.W.; Ginindza, T.G. Motivators and Influencers of Adolescent Girls’ Decision Making Regarding Contraceptive Use in Four Districts of Zambia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, L.K.; Maness, S.B.; Sundstrom, B. Contraception Knowledge among College Women in the Southeast United States. J. Am. Coll. Health 2025, 73, 1010–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzak, B.; Zgórecki, P. Prophylactic Mastectomy and Ovariectomy—A Religious Perspective. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2021, 42, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Song, H. Adult Female Callers’ Characteristics and Mental Health Status: A Retrospective Study Based on the Psychological Assistance Hotline in Hangzhou. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.J. Knowing and Not Knowing about Fertility: Childless Women and Age-Related Fertility Decline. A&A 2021, 42, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, D.C.; Boyko, S.; Torchetti, T.; McBain, S.; Benko, S.; Khan, I.; Ye, X.Y.; Quartey, N.K.; Poznanski, D.; MacKinnon, K.; et al. Fertility Information Perceptions and Needs of People with Cancer, Their Family Members, and Caregivers. Support Care Cancer 2025, 33, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Cao, J.; Nie, W.; Wang, X.; Tian, Y.; Ma, C. The Influence of Internet Usage Frequency on Women’s Fertility Intentions—The Mediating Effects of Gender Role Attitudes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, L.; Rabinor, R. Fertility Counseling with Groups. In Fertility Counseling: Clinical Guide; Covington, S.N., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 59–67. ISBN 978-1-009-03015-1. [Google Scholar]

- Costa Figueiredo, M.; Su, H.I.; Chen, Y. Using Data to Approach the Unknown: Patients’ and Healthcare Providers? Data Practices in Fertility Challenges. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Interact. 2021, 4, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Chan, C.H.Y.; Hou, Y.; Chan, C.L.W. Ambivalence Experienced by Infertile Couples Undergoing IVF: A Qualitative Study. Hum. Fertil. 2023, 26, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.L.; Moss, R.H.; Darby, F.; Mahmoodi, N.; Phillips, B.; Hughes, J.; Vogt, K.S.; Greenfield, D.M.; Brauten-Smith, G.; Gath, J.; et al. Cancer, Fertility and Me: Developing and Testing a Novel Fertility Preservation Patient Decision Aid to Support Women at Risk of Losing Their Fertility Because of Cancer Treatment. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 896939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagiv, L.; Roccas, S. How Do Values Affect Behavior? Let Me Count the Ways. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 25, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagiv, L.; Schwartz, S.H. Personal Values Across Cultures. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2022, 73, 517–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Park, S.; Kim, S.H. Supporting Decision-making Regarding Fertility Preservation in Patients with Cancer: An Integrative Review. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2022, 31, e13748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Remains Firmly Committed to the Principles Set out in the Preamble to the Constitution; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Alzeer, J. Integrating Medicine with Lifestyle for Personalized and Holistic Healthcare. J. Pub. Health Emerg. 2023, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Nzegwu, D.; Wright, M.L. The Impact of Psychosocial Stress from Life Trauma and Racial Discrimination on Epigenetic Aging—A Systematic Review. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2022, 24, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Record, J.D.; Ziegelstein, R.C. Personomics: The Personalization of Precision Medicine. In Implementation of Personalized Precision Medicine; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 407–415. ISBN 978-0-323-98808-7. [Google Scholar]

- Delpierre, C.; Lefèvre, T. Precision and Personalized Medicine: What Their Current Definition Says and Silences about the Model of Health They Promote. Implication for the Development of Personalized Health. Front. Sociol. 2023, 8, 1112159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, G.; Bitew, M. Revolutionizing Personalized Medicine: Synergy with Multi-Omics Data Generation, Main Hurdles, and Future Perspectives. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, D.L. The True ART: How to Deliver the Best Patient Care. In The Boston IVF Handbook of Infertility; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 272–280. ISBN 978-1-003-46027-5. [Google Scholar]

- John, J.N.; Gorman, S.; Scales, D.; Gorman, J. Online Misleading Information About Women’s Reproductive Health: A Narrative Review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2025, 40, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athey, S.; Bergstrom, K.; Hadad, V.; Jamison, J.C.; Özler, B.; Parisotto, L.; Sama, J.D. Can Personalized Digital Counseling Improve Consumer Search for Modern Contraceptive Methods? Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadg4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Tang, L.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, X. Self-Disclosure and Received Social Support among Women Experiencing Infertility on Reddit: A Natural Language Processing Approach. Comp. Hum. Behav. 2024, 154, 108159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulletti, C. Telemedicine in IVF Programs. BJSTR 2023, 51, 42611–42618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Regarding the UN Sustainable Goals of Well-Being, Gender Equality, and Climate Action: Reconsidering Reproductive Expectations of Women Worldwide. Sexes 2025, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Unresolved Depression on Alleviating Health Research Burnout. J. Biomed. Res. Environ. Sci. 2025, 6, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Challenges Identifying and Stimulating Self-Directed Learning in Publicly Funded Programs. In The Digital Era of Learning: Novel Educational Strategies and Challenges for Teaching Students in the 21st Century; Keator, C.S., Ed.; Education in a competitive and globalizing world; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 259–300. ISBN 978-1-5361-8750-2. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, C. Report on Digital Literacy in Academic Meetings during the 2020 COVID-19 Lockdown. Challenges 2020, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, S.B.; Howe, L.W.; Kirschenbaum, H. Values Clarification; Warner Books: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-446-56525-7. [Google Scholar]

- Raths, L.E.; Harmin, M.; Simon, S.B. Values and Teaching: Working with Values in the Classroom, 1st ed.; C.E. Merrill Books: Columbus, OH, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- MDPI. MDPI Review Reports. In Guidelines for Reviewers; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Josselson, R.; Hammack, P.L. Essentials of Narrative Analysis; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-4338-3567-4. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, N.; Venkatesan, S. Reproductive Autonomy, Graphic Reproduction, and The Elephant in the Womb. Perspect. Biol. Med. 2025, 68, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Team Mindfulness in Online Academic Meetings to Reduce Burnout. Challenges 2023, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Historical Study of an Online Hospital-Affiliated Burnout Intervention Process for Researchers. J. Hosp. Manag. Health Policy 2024, Online first, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. COVID-19 Limitations on Doodling as a Measure of Burnout. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 1688–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nash, C. Doodling as a Measure of Burnout in Healthcare Researchers. Cult. Med. Psych. 2021, 45, 565–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Online Meeting Challenges in a Research Group Resulting from COVID-19 Limitations. Challenges 2021, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Enhancing Hopeful Resilience Regarding Depression and Anxiety with a Narrative Method of Ordering Memory Effective in Researchers Experiencing Burnout. Challenges 2022, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, T.S.; Close, J.; Bylund, C.L. Skills-Based Programs Used to Reduce Physician Burnout in Graduate Medical Education: A Systematic Review. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2021, 13, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witteman, H.O.; Ndjaboue, R.; Vaisson, G.; Dansokho, S.C.; Arnold, B.; Bridges, J.F.P.; Comeau, S.; Fagerlin, A.; Gavaruzzi, T.; Marcoux, M.; et al. Clarifying Values: An Updated and Expanded Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med. Decis. Mak. 2021, 41, 801–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, J.C.; Botero-Meneses, J.S. An Online Survey of UK Women’s Attitudes to Having Children, the Age They Want Children and the Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Hum. Reprod. 2022, 37, 2611–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger, A.S. Artificial Intelligence vs. Human Coaches: Examining the Development of Working Alliance in a Single Session. Front. Psychol. 2025, 15, 1364054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.N.; Grande, S.; Nakamura, Y.T.; Pyle, L.; Shaw, G. The Development and Practice of Authentic Leadership: A Cultural Lens. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2022, 46, 937–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, M.; Timmins, F.; Wise, P.Y.; Stokes, D.; Alharbi, T.A.F. Authentic Leadership—A Concept Analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025, 81, 1775–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.K.C.; Sriphon, T. Authentic Leadership, Trust, and Social Exchange Relationships under the Influence of Leader Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunyemi, O.; Ogunyemi, K. Authentic Leadership: Leading with Purpose, Meaning and Core Values. In New Horizons in Positive Leadership and Change; Dhiman, S., Marques, J., Eds.; Management for Professionals; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 369–380. ISBN 978-3-030-38128-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, L. Authentic Leadership: Roots of the Construct. In Mindfulness for Authentic Leadership; Palgrave Studies in Workplace Spirituality and Fulfillment; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 17–52. ISBN 978-3-031-34676-7. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, K.L.; Devnew, L.E. Developing Responsible, Self-Aware Management: An Authentic Leadership Development Program Case Study. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.A.; Bloomer, F.; Pétursdóttir, G.M. “For Some Reason, She Just Wasn’t Able to Have an Abortion”: Social Attitudes, Reproductive Autonomy, and the Taboo of Regret. Sex Roles 2025, 91, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, N.N.; Klosky, J.L.; Meacham, L.R.; Quinn, G.P.; Kelvin, J.F.; Cherven, B.; Freyer, D.R.; Dvorak, C.C.; Brackett, J.; Ahmed-Winston, S.; et al. Infrastructure of Fertility Preservation Services for Pediatric Cancer Patients: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. JCO Oncol. Prac. 2022, 18, e325–e333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Leite, M.; Costa, R.; Figueiredo, B.; Gameiro, S. Discussing the Possibility of Fertility Treatment Being Unsuccessful as Part of Routine Care Offered at Clinics: Patients’ Experiences, Willingness, and Preferences. Hum. Reprod. 2023, 38, 1332–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluth, N.P. Reframing as Recourse: How Women Approach and Initiate the End of Fertility Treatment. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 338, 116310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.M.; Lee, R.R.; McBeth, J.; James, B.; McAlister, S.; Chiarotto, A.; Dixon, W.G.; Van Der Veer, S.N. Exploring the Cross-Cultural Acceptability of Digital Tools for Pain Self-Reporting: Qualitative Study. JMIR Hum. Factors 2023, 10, e42177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, R.W. Convenience Sampling Revisited: Embracing Its Limitations Through Thoughtful Study Design. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 2021, 115, 76–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, C.R.; Johnson-Koenke, R. Narrative Inquiry as a Caring and Relational Research Approach: Adopting an Evolving Paradigm. Qual. Health Res. 2023, 33, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, M. Quality Indicators in Narrative Research. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutsyuruba, B.; Stasel, R.S. Narrative Inquiry. In Varieties of Qualitative Research Methods; Okoko, J.M., Tunison, S., Walker, K.D., Eds.; Springer Texts in Education; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 325–332. ISBN 978-3-031-04396-3. [Google Scholar]

- Pino Gavidia, L.A.; Adu, J. Critical Narrative Inquiry: An Examination of a Methodological Approach. Int. J. Qual. Meth. 2022, 21, 16094069221081594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M. What Is Qualitative Research? An Overview and Guidelines. Australas. Mark. J. 2025, 33, 199–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuzer, M. The Grammar of Time: A Toolbox for Comparative Historical Analysis, 1st ed.; Methods for Social Inquiry Series; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; ISBN 978-1-108-71823-3. [Google Scholar]

- Sukhera, J. Narrative Reviews: Flexible, Rigorous, and Practical. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022, 14, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, R.M.; Rajan, P.; Gamage, L. Redressing Historical Bias: Exploring the Path to an Accurate Representation of the Past. J. Soc. Sci. 2023, 4, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, A.D. Methodology: Foundations of Inference and Research in the Behavioral Sciences; De Gruyter: New York, NY, USA, 1969; ISBN 978-3-11-231312-1. [Google Scholar]

| HeNReG: 2020–2022 | HeNReP 2022–2025 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020/2021 | 2021/2022 | 2022/2023 | 2023/2024 | 2024/2025 | |

| Participants | 20 | 19 | 7 | 7 | 2 |

| Completed | 15 (75%) | 15 (79%) | 4 (57%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (50%) |

| Female | 13 (65%) | 12 (63%) | 6 (86%) | 5 (71%) | 2 (100%) |

| Female completed | 10 (67%) | 9 (60%) | 4 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (50%) |

| HeNReG: 2020–2022 | HeNReP 2022–2025 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020/2021 | 2021/2022 | 2022/2023 | 2023/2024 | 2024/2025 | |

| Participant 1 | X | X | |||

| Participant 2 | X | X | |||

| # | Demographic | Description of Research Related to Health | Perceived HeNReG Participant Reasons for Their Non-Burnout-Related Depression | Perceived HeNReP Participant Reasons for Inability to Schedule Meetings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Middle-aged Graduate student | Developing a teaching framework for learning about life, health, and death through somatic experience | Acting as the caregiver for a parent with terminal illness, with a lack of effective family support | Overwhelmed from death of parent with the terminal illness for whom caregiving was provided |

| 2 | Middle-aged Neurodivergent Social worker | Investigating social justice. Working primarily with people living in poverty, the ethical dilemmas… supporting people through their voice, tying in narrative concepts and models | Deficient sibling support for neurodivergence | Organizing and scheduling are a challenge because of difficulties with conceptualizing time and the steps to follow |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nash, C. A Suggested One-On-One Method Providing Personalized Online Support for Females Clarifying Their Fertility Values. Women 2025, 5, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5040044

Nash C. A Suggested One-On-One Method Providing Personalized Online Support for Females Clarifying Their Fertility Values. Women. 2025; 5(4):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5040044

Chicago/Turabian StyleNash, Carol. 2025. "A Suggested One-On-One Method Providing Personalized Online Support for Females Clarifying Their Fertility Values" Women 5, no. 4: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5040044

APA StyleNash, C. (2025). A Suggested One-On-One Method Providing Personalized Online Support for Females Clarifying Their Fertility Values. Women, 5(4), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5040044