Social Support and Mental Well-Being of Newcomer Women and Children Living in Canada: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

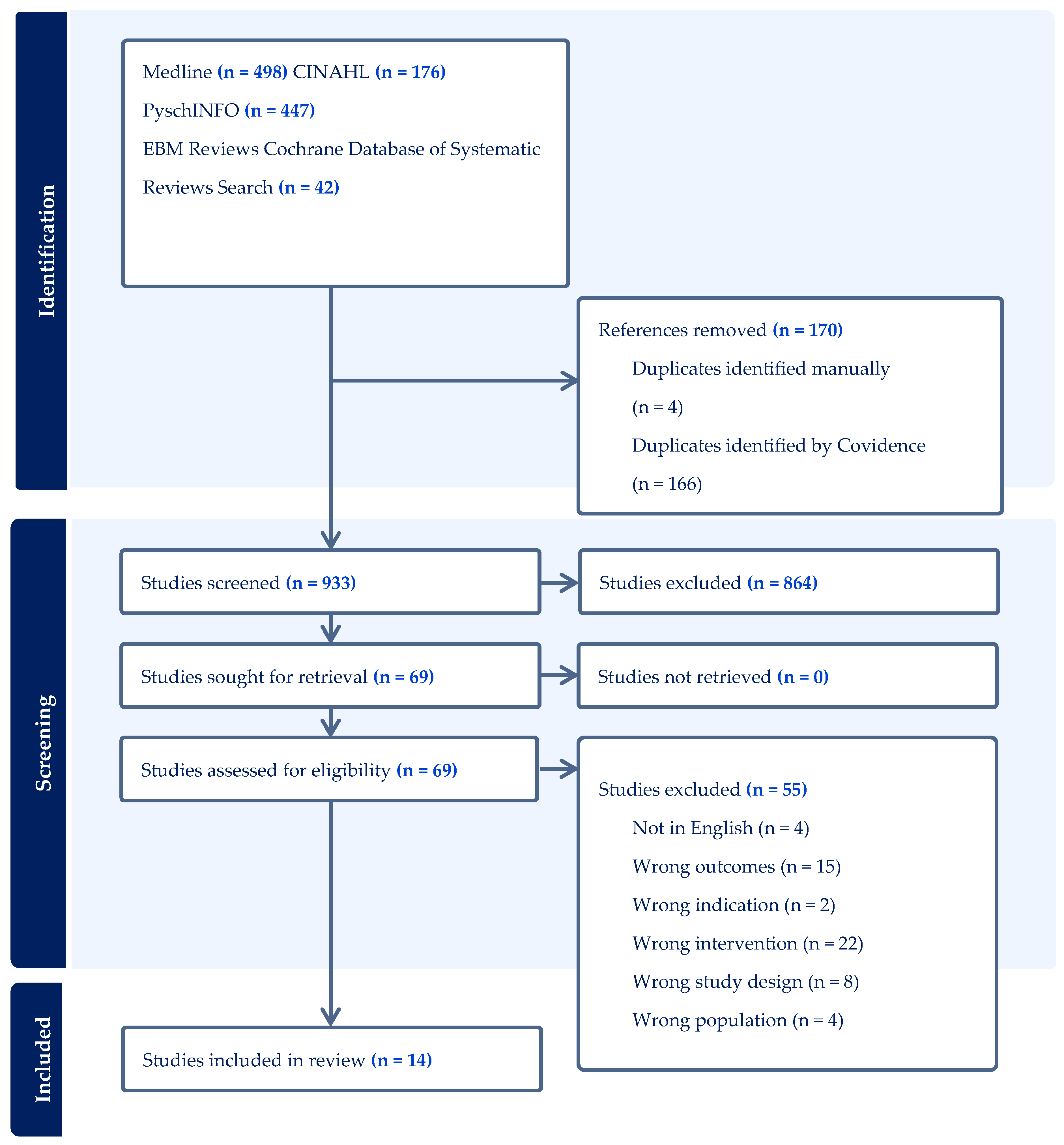

2.1. Study Selection

2.2. Study Characteristics

2.3. Types of Interventions

2.3.1. Group Art-Based Interventions

2.3.2. Support Group and Workshop Participation

2.3.3. Assessment of Existing Social Support Services and Programs

2.3.4. Social Media Intervention

2.3.5. Short-Term Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Question

3.2. Searching Relevant Studies

3.3. Selecting Studies/Inclusion Criteria

3.3.1. Types of Studies

3.3.2. Interventions and Comparators

3.3.3. Outcomes

3.3.4. Participants

3.3.5. Context

3.3.6. Study Selection

3.4. Data Extraction

3.5. Data Synthesis

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goodman, S.H.; Simon, H.F.M.; Shamblaw, A.L.; Kim, C.Y. Parenting as a Mediator of Associations between Depression in Mothers and Children’s Functioning: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 23, 427–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herba, C.M.; Glover, V.; Ramchandani, P.G.; Rondon, M.B. Maternal Depression and Mental Health in Early Childhood: An Examination of Underlying Mechanisms in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, S.H.; Rouse, M.H.; Connell, A.M.; Broth, M.R.; Hall, C.M.; Heyward, D. Maternal Depression and Child Psychopathology: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 14, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virupaksha, H.G.; Kumar, A.; Nirmala, B.P. Migration and Mental Health: An Interface. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2014, 5, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezazadeh, M.S.; Hoover, M.L. Women’s Experiences of Immigration to Canada: A Review of the Literature. Can. Psychol./Psychol. Can. 2018, 59, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada, S.C. The Daily—Immigrants Make up the Largest Share of the Population in over 150 Years and Continue to Shape Who We Are as Canadians. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221026/dq221026a-eng.htm (accessed on 8 October 2023).

- Statistics Canada. Canada at a Glance, 2022 Women. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/12-581-x/2022001/sec7-eng.htm (accessed on 8 October 2023).

- Statistics Canada. Projections of the Diversity of the Canadian Population, 2006–2031. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/91-551-x/91-551-x2010001-eng.htm (accessed on 29 November 2023).

- Government of Canada, S.C. Female Population. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-503-x/2015001/article/14152-eng.htm (accessed on 29 November 2023).

- Statistics Canada. Visible Minority of Person. Available online: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Var.pl?Function=DECI&Id=257515 (accessed on 29 November 2023).

- Dobrowolsky, A.; Arat-Koç, S.; Gabriel, C. Newcomer Families’ Experiences with Programs and Services to Support Early Childhood Development in Canada: A Scoping Review|Journal of Childhood, Education & Society. Available online: https://www.j-ces.com/index.php/jces/article/view/49 (accessed on 29 November 2023).

- Robert, A.; Gilkinson, T. Mental Health and Well-Being of Recent Immigrants in Canada: Evidence from the Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada (LSIC). Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/reports-statistics/research/mental-health-well-being-recent-immigrants-canada-evidence-longitudinal-survey-immigrants-canada-lsic.html (accessed on 29 November 2023).

- Harandi, T.F.; Taghinasab, M.M.; Nayeri, T.D. The Correlation of Social Support with Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis. Electron. Physician 2017, 9, 5212–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychological Association. APA Dictionary of Psychology. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/ (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Shan, H. Shaping the Re-training and Re-education Experiences of Immigrant Women: The Credential and Certificate Regime in Canada. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2009, 28, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simich, L.; Beiser, M.; Stewart, M.; Mwakarimba, E. Providing Social Support for Immigrants and Refugees in Canada: Challenges and Directions. J. Immigr. Health 2005, 7, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, M.; Simich, L.; Shizha, E.; Makumbe, K.; Makwarimba, E. Supporting African Refugees in Canada: Insights from a Support Intervention. Health Soc. Care Community 2012, 20, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.; Mildon, A.; Stewart, S.; Underhill, B.; Tarasuk, V.; Di Ruggiero, E.; Sellen, D.; O’Connor, D.L. Vulnerable Mothers’ Experiences Breastfeeding with an Enhanced Community Lactation Support Program. Matern. Child Nutr. 2020, 16, e12957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodgate, R.L.; Zurba, M.; Tennent, P.; Cochrane, C.; Payne, M.; Mignone, J. A Qualitative Study on the Intersectional Social Determinants for Indigenous People Who Become Infected with HIV in Their Youth. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killian, K.D.; Lehr, S. The Resettlement Blues: The Role of Social Support in Newcomer Women’s Mental Health. In Women’s Mental Health: Resistance and Resilience in Community and Society; Springer International Publishing/Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerlands, 2015; pp. 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, N.; Carroll, S.; Aljbour, R.; Nair, K.; Wahoush, O. Adult Newcomers’ Perceptions of Access to Care and Differences in Health Systems after Relocation from Syria. Confl. Health 2022, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creese, G.; Wiebe, B. ‘Survival Employment’: Gender and Deskilling among African Immigrants in Canada. Int. Migr. 2012, 50, 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M.S.; Chaze, F.; George, U.; Guruge, S. Improving Immigrant Populations’ Access to Mental Health Services in Canada: A Review of Barriers and Recommendations. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2015, 17, 1895–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mental Health Commission of Canada. Immigrant, Refugee, Ethnocultural and Racialized Population and the Social Determinants of Health: A Review of 2016 Census Data; Legal Deposit National Library of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sim, A.; Ahmad, A.; Hammad, L.; Shalaby, Y.; Georgiades, K. Reimagining Mental Health Care for Newcomer Children and Families: A Qualitative Framework Analysis of Service Provider Perspectives. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, E.; Zhang, H. Access to Mental Health Consultations by Immigrants and Refugees in Canada. Health Rep. 2021, 32, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salam, Z.; Odenigbo, O.; Newbold, B.; Wahoush, O.; Schwartz, L. Systemic and Individual Factors That Shape Mental Health Service Usage Among Visible Minority Immigrants and Refugees in Canada: A Scoping Review. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2022, 49, 552–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkchirid PhD, A.; Motia MA, M. Condors and Tigers: A Literature Review on Arts, Social Support, and Mental Health among Immigrant Children in Canada. Soc. Work Ment. Health 2022, 20, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauregard, C.; Rousseau, C.; Benoit, M.; Papazian-Zohrabian, G. Creating a Safe Space during Classroom-Based Sandplay Workshops for Immigrant and Refugee Preschool Children. J. Creat. Ment. Health 2022, 19, 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerami, M. The Effects of Group Art Therapy on Reducing Psychological Stress and Improving the Quality of Life in Iranian Newcomer Children = Les Effets de l’art-Thérapie de Groupe Sur La Réduction Du Stress Psychologique et l’amélioration de La Qualité de Vie d’enf. Can. J. Art Ther. Res. Pract. Issues 2021, 34, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanania, A. Embroidery (Tatriz) and Syrian Refugees: Exploring Loss and Hope Through Storytelling. Can. Art Ther. Assoc. J. 2020, 33, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas Girardi, J.; Miconi, D.; Lyke, C.; Rousseau, C. Creative Expression Workshops as Psychological First Aid (PFA) for Asylum-Seeking Children: An Exploratory Study in Temporary Shelters in Montreal. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herati, H.; Meyer, S.B. Mental Health Interventions for Immigrant-Refugee Children and Youth Living in Canada: A Scoping Review and Way Forward. J. Ment. Health 2023, 32, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, M.; Spitzer, D.L.; Kushner, K.E.; Shizha, E.; Letourneau, N.; Makwarimba, E.; Dennis, C.-L.; Kariwo, M.; Makumbe, K.; Edey, J. Supporting Refugee Parents of Young Children: “Knowing You’re Not Alone”. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care 2018, 14, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pino-Brunet, N.; Hombrados-Mendieta, I.; Gomez-Jacinto, L.; Garcia-Cid, A.; Millan-Franco, M. Systematic Review of Integration and Radicalization Prevention Programs for Migrants in the US, Canada, and Europe. Front. Psychiatr. 2021, 12, 606147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, M.; Makwarimba, E.; Letourneau, N.L.; Kushner, K.E.; Spitzer, D.L.; Dennis, C.-L.; Shizha, E. Impacts of a Support Intervention for Zimbabwean and Sudanese Refugee Parents: “I Am Not Alone. ” Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2015, 47, 113–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohr, Y.; Bimm, M.; Bint Misbah, K.; Perrier, R.; Lee, Y.; Armour, L.; Sockett-DiMarco, N. The Crying Clinic: Increasing Accessibility to Infant Mental Health Services for Immigrant Parents at Risk for Peripartum Depression. Infant Ment. Health J. 2021, 42, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesanti, S.R.; Abelson, J.; Lavis, J.N.; Dunn, J.R. Enabling the Participation of Marginalized Populations: Case Studies from a Health Service Organization in Ontario, Canada. Health Promot. Int. 2017, 32, 636–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaher, Z. Examining How Newcomer Women to Canada Use Social Media for Social Support. Can. J. Commun. 2020, 45, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, J.; Lee, E. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for a Refugee Mother with Depression and Anxiety. Clin. Case Stud. 2020, 19, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software. Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available online: www.covidence.org. (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Giesbrecht, C.J.; Kikulwe, D.; Watkinson, A.M.; Sato, C.L.; Este, D.C.; Falihi, A. Supporting Newcomer Women Who Experience Intimate Partner Violence and Their Children: Insights From Service Providers. Affilia 2023, 38, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, V.; Pigeon, C.; Rony, F.; Fort-Talabard, A. Designing a Creative Storytelling Workshop to Build Self-Confidence and Trust among Adolescents. Think. Ski. Creat. 2020, 38, 100704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, N.A.; Huen, N.; Vallani, T.; Herath, J.; Jhauj, R. A Proposal to Optimize Satisfaction and Adherence in Group Fitness Programs For Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2023, 29, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falah-Hassani, K.; Shiri, R.; Vigod, S.; Dennis, C.-L. Prevalence of Postpartum Depression among Immigrant Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 70, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salami, B.; Salma, J.; Hegadoren, K. Access and Utilization of Mental Health Services for Immigrants and Refugees: Perspectives of Immigrant Service Providers. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shensa, A.; Sidani, J.E.; Escobar-Viera, C.G.; Switzer, G.E.; Primack, B.A.; Choukas-Bradley, S. Emotional Support from Social Media and Face-to-Face Relationships: Associations with Depression Risk among Young Adults. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 260, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Intervention | Author | Aim | Intervention Duration | Setting | Participants | Design | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group Art based interventions | Elkchrid and Motia [28] | To understand how participation in group-based arts programs impacts the mental health of immigrant children in Canada | - | - | - | Literature review | Enhanced self-esteem and emotional expression, promoted social understanding among teachers and students, and aided children in coping with immigration challenges, and proved beneficial for children with ADHD. |

| Beauregard [29] | To understand positive impacts, challenges and opportunities of implementing sandplay in non-clinical settings | 10 weeks | Preschool classroom Quebec | 63 children | Qualitative; documented children’s storytelling through sand play | Provided a safe space for children to express their identity, emotions, and experience of violence non-verbally. | |

| Gerami [30] | Examine the effects of group art therapy on reducing psychological stress and improving quality of life in Iranian child immigrants and refugees | 10 weeks | Schools, Quebec | 10 children aged 8–12 | Quantitative; saliva testing and psychometric measures | Significantly improved quality of life and decreased perceived stress and cortisol levels among children; results were retained at a 4-week follow-up. | |

| Hanania [31] | To describe a woman’s embroidery program that provided art therapy as a way to process feelings of hope and loss. | 12 weeks | Community, Ontario | 11 Arabic-speaking women aged 22–53 | Qualitative; Interviews and feedback regarding sessions | Created feelings of community, friendship, support, beneficial social interaction, and a decrease in loneliness. Creating embroidery produced feelings of accomplishment and a connection to culture/homeland. | |

| de Freitas Girardi [32] | To assess whether creative expressive workshops met core elements of psychological first aid and were able to support diverse needs of asylum-seeking youth. | 6 months | Various asylum-seeking shelters, Montreal | Children and adolescents living in temporary shelters for refugees and migrants | Qualitative; field notes and interviews | Children expressed negative emotions such as anger, sadness, and fear without pushing disclosure. | |

| Herati [33] | To understand the psychosocial needs of immigrant-refugee children and identify the characteristics of school/community-based mental health programs | - | - | 15 articles published between January 2010–December 2018 | Scoping Review | Sand play, storytelling, drama and play-based programs reduced impairment, enhanced empowerment, and coping skills, and provided culturally appropriate and ethical methods for understanding the impacts of trauma on immigrant and refugee children. | |

| Support Groups and Workshops | Stewart [34] | To develop and evaluate an accessible and culturally appropriate social support intervention designed to meet the support needs and preferences identified by African refugee parents of young children. | 8 face-to-face support groups | Alberta and Ontario | 85 Sudanese and Zimbabwean refugees (38 women) | Qualitative: social support group | Women found support group meetings to be a valuable source of emotional support and advice for addressing challenges such as language barriers, parenting, healthcare, and maintaining cultural traditions. |

| Del-Pino-Brunet [35] | To analyze intervention programs that aim at promoting social integration and preventing the radicalization of migrants in Canada. | - | - | 18 papers published before January 2019 | Systematic review | Despite limitations, programs targeting migrant women and children yielded positive outcomes, e.g., increased social support, reduced loneliness and depression, improved quality of life, integration, enhanced knowledge, self-esteem, and coping abilities. | |

| Stewart [36] | To design and evaluate an accessible and culturally appropriate social support intervention that meets the support needs and preferences identified by Zimbabwean and Sudanese refugee parents. | 7 months | Alberta and Ontario | 5 new parents; new to Canada; had a preschool child between the ages of 4 months and 5 years born in Canada | Pilot intervention | Culturally sensitive interventions created a space for participants to share information on relevant resources, learn how to improve spousal/familial relationships and cope with parenting stress. Meetings decreased loneliness and isolation and enhanced coping strategies for refugee parents. | |

| Stewart [17] | To design and pilot a culturally congruent intervention that meets the support needs and preferences of two ethnocultural distinct refugee groups. | 12 weeks | Participants homes/community agencies, western and central Canada. | 58 (27 women) Somali and Southern Sudanese refugees lived in Canada for 10 years or less | Qualitative: face-to-face and telephone support intervention | Newcomer women benefited from information about support resources highlighted in group discussions. Support group fostered acceptance, peer support and provided safe space to share emotions and advice regarding conflict management, financial counseling, school-related issues, and the need for better inclusion of refugee parents in school planning. | |

| Assessment of Social Support Services | Bohr [37] | To pilot test an initiative aimed to provide an intervention that could enhance infant and family mental health, and healthy child development in a new generation of citizens. | March 2014–August 2016 | Clinic, Ontario | 44 new immigrant and highly stressed parents and their infants | Mixed-methods | Client-centered approach effectively made mental health support more accessible to newcomer women and parents by reducing stigma and providing culturally appropriate therapy. 72% of clients reported that their individual and cultural needs were significantly met during the intervention. |

| Montesanti [38] | Investigate approaches, strategies, and methods health service organizations use to engage marginalized populations. | November 2011–February 2012 | Various community health centers, Ontario | 4 in depth case studies of community participation initiatives | Case series | Significant barriers to participation for marginalized women included a lack of targeted services for women, language barriers, financial constraints, and mental stress. Programs addressed these by aiming to build on community-based methods, and peer facilitator and community stakeholder partnerships. | |

| Social Media Interventions | Zaher [39] | To examine how newcomer women use social media for support to enhance their mental well-being. | 4 weeks. | Ontario | 17 newcomer women were recruited using a recruitment flyer | Qualitative | Newcomer women used social media for relaxation, venting and practical purposes. Some refugee women avoided it to protect themselves from cyber harassment and surveillance. |

| Short-term Cognitive Behavioral Therapy | Faber [40] | To illustrate a short-term cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for a refugee single mother of a 4-year-old son to address depression and anxiety symptoms. | 10 sessions. | Not disclosed | 29-year-old single woman, with 13-year history of anxiety and depression symptoms | Mixed methods | 10 sessions of CBT improved symptoms of depression and anxiety from severe to mild. |

| Row No# | Search Terms | Row No | Search Terms |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | emigrants and immigrants/or undocumented immigrants/or refugees | 10 | Individual or group or peer support or open group or close group or facilitated support group or education series). |

| 2 | Newcomer or immigrant or refugee or migrant or settler or nomad or migrating or asylum seeker or incomer | 11 | mental health/or resilience, psychological/or exp Self Concept/or exp “Quality of Life”/ |

| 3 | 1 or 2 | 12 | Mental health outcomes or resilience or self-efficacy or coping or self-esteem or social connections or quality of life or improvement in mental health issues or improvement in mental health challenges or depression or anxiety or mood or mental health or wellbeing or welfare or mental illness |

| 4 | Mother */ | 13 | 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 |

| 5 | Women or mother or biological mother or female parent or matriarch or mamma or mama or child * or son or daughter or offspring | 14 | exp Canada/ |

| 6 | 4 or 5 | 15 | Canad * or British Columbia or Colombie Britannique or Alberta or Saskatchewan or Manitoba or Ontario or Quebec or Nova Scotia or New Brunswick or Newfoundland or Labrador or Prince Edward Island or Yukon Territory or NWT or Northwest Territories or Nunavut or Nunavik or Nunatsiavut or NunatuKavut |

| 7 | exp Social Support */or exp social welfare/or exp social work */ | 16 | 14 or 15 |

| 8 | Social support interventions or Social Support or social assistance or social aid or social care or social service or general support or safety net or interventions or measures or strategies | 17 | 3 and 6 and 13 and 16 |

| 9 | peer group/or peer influence/or Self-Help Groups/ | 18 | limit 17 to yr = “2012–Current” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hirani, S.; Shah, Z.; Dubicki, T.C.; Bandara, N.A. Social Support and Mental Well-Being of Newcomer Women and Children Living in Canada: A Scoping Review. Women 2024, 4, 172-187. https://doi.org/10.3390/women4020013

Hirani S, Shah Z, Dubicki TC, Bandara NA. Social Support and Mental Well-Being of Newcomer Women and Children Living in Canada: A Scoping Review. Women. 2024; 4(2):172-187. https://doi.org/10.3390/women4020013

Chicago/Turabian StyleHirani, Saima, Zara Shah, Theresa Claire Dubicki, and Nilanga Aki Bandara. 2024. "Social Support and Mental Well-Being of Newcomer Women and Children Living in Canada: A Scoping Review" Women 4, no. 2: 172-187. https://doi.org/10.3390/women4020013

APA StyleHirani, S., Shah, Z., Dubicki, T. C., & Bandara, N. A. (2024). Social Support and Mental Well-Being of Newcomer Women and Children Living in Canada: A Scoping Review. Women, 4(2), 172-187. https://doi.org/10.3390/women4020013