Choice of Non-Disclosure as Agency: A Systematic Review of Non-Disclosure of Sexual Violence in Girlhood in Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Conceptualization of Violence

2.2. Relationship with Perpetrator

2.3. Street Culture That Normalizes Rape

2.4. Institutional Contexts Unfavorable for Disclosure

2.5. Ineffective Justice Seeking Processes

2.6. Sexual Violence-Related Stigma

2.7. Blaming and Threats/Blackmail

“I was raped, or will I say used. One distant uncle of mine has been having sexual intercourse with me since he brought me from home. One day, the junior brother of his wife caught us in the act and he threatened to report to the sister unless I allow him to have his way, i.e., have sexual intercourse with me. I allowed him because I dread the sister, who is very wicked. Since then, I have been doing it with the two of them. It is painful, I do not know whom to tell, I only want to run away from home and go back to the village and stay with my parents” [p. 257].

3. Discussion

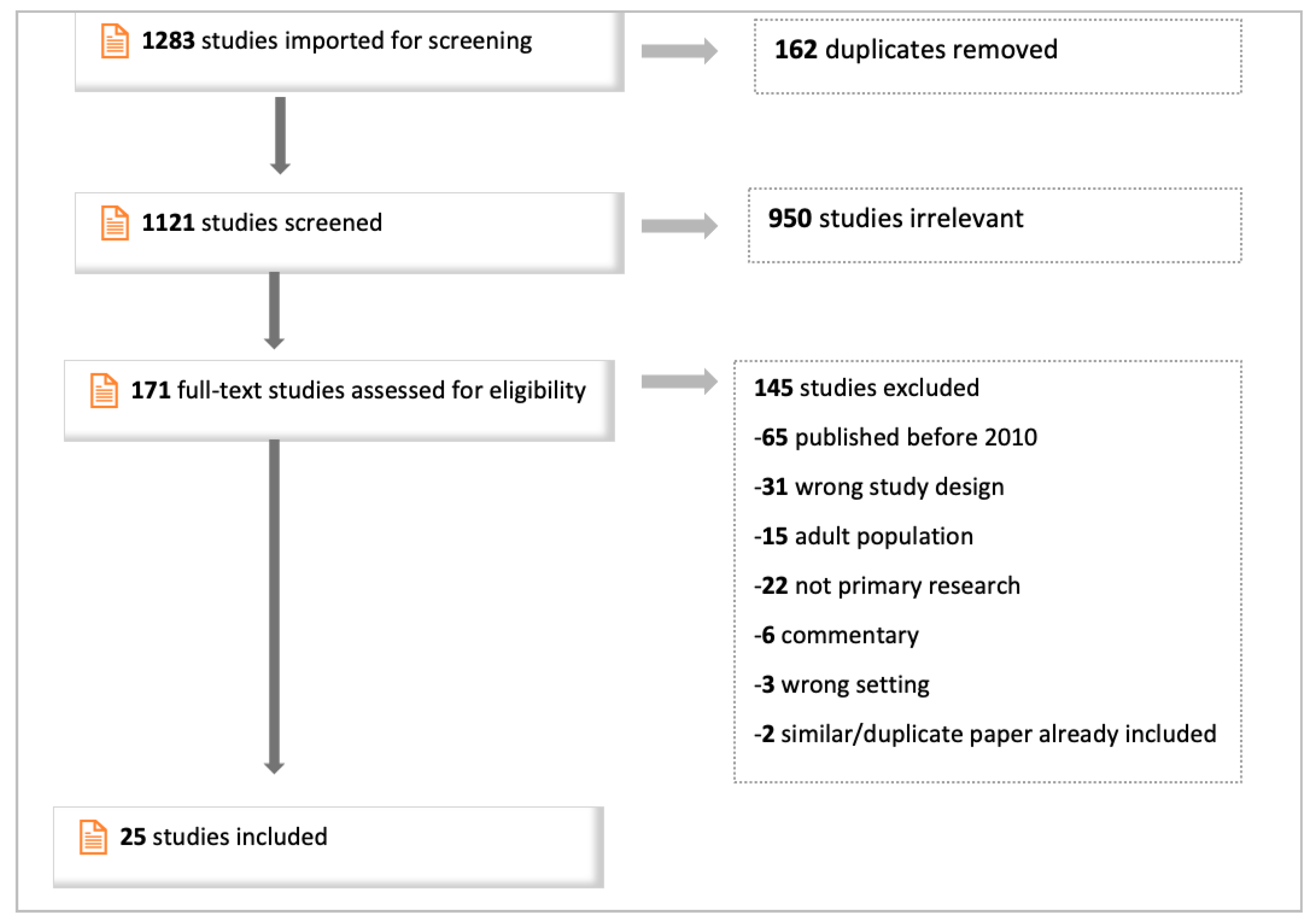

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (UNDESA). World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/423); United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hillis, S.; Mercy, J.; Amobi, A.; Kress, H. Global Prevalence of Past-year Violence Against Children: A Systematic Review and Minimum Estimates. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20154079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Together for Girls. About the Violence against Children and Youth Surveys. Available online: https://www.togetherforgirls.org/en/about-the-vacs (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Ligiero, D.; Hart, C.; Fulu, E.; Thomas, A.; Radford, L. What Works to Prevent Sexual Violence against Children. Together for Girls. 2019. Available online: https://www.togetherforgirls.org/en/resources/what-works-to-prevent-sexual-violence-against-children-evidence-review (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- World Health Organization. INSPIRE: Seven Strategies for Ending Violence against Children; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://files.mutualcdn.com/tfg/assets/files/INSPIRE-Report.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- UN General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of the Child; Treaty Series; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 1989; Volume 1577. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 21 October 2015. A/RES/70/1. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/57b6e3e44.html (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- African Union. African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child; African Union: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child. AGENDA 2040, Africa’s Agenda for children: Fostering an Africa Fit for Children. 9 November 2016. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/5836c7ee4.html (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). Protecting Children from Violence in the Time of COVID-19: Disruptions in Prevention and Response Services; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- African Child Policy Forum. The African Report on Child Wellbeing 2020: How Friendly Are African Governments towards Girls? African Child Policy Forum: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ellsberg, M.; Ovince, J.; Murphy, M.; Blackwell, A.; Reddy, D.; Stennes, J.; Hess, T.; Contreras, M. No safe place: Prevalence and correlates of violence against conflict-affected women and girls in South Sudan. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalisya, L.M.; Justin, P.L.; Kimona, C.; Nyavandu, K.; Eugenie, K.M.; Jonathan, K.M.L.; Claude, K.M.; Hawkes, M. Sexual Violence toward Children and Youth in War-Torn Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e15911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, L.; Robinson, M.V.; Seff, I.; Gillespie, A.; Colarelli, J.; Landis, D. The Effectiveness of Women and Girls Safe Spaces: A Systematic Review of Evidence to Address Violence Against Women and Girls in Humanitarian Contexts. Trauma Violence Abus. 2022, 23, 1249–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karen, W. Children’s experiences of sexual violence, psychological trauma, death, and injury in war. Confl. Violence Peace 2017, 11, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Nyangoma, A.; Ebila, F.; Omona, J. Child Sexual Abuse and Situational Context: Children’s Experiences in Post-Conflict Northern Uganda. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2019, 28, 907–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohito, S. Violence against Children in Africa. In Violence Against Children: Making Human Rights Real, 1st ed.; Lenzer, G., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2017; pp. 104–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.K.; Nordås, R. Sexual violence in armed conflict: Introducing the SVAC dataset, 1989–2009. J. Peace Res. 2014, 51, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, C.D. The ties that bind: How armed groups use violence to socialize fighters. J. Peace Res. 2017, 54, 701–714. [Google Scholar]

- Baaz, M.E.; Gray, H.; Stern, M. What can we/do we want to know? Reflections from researching SGBV in military settings. Soc. Politics Int. Stud. Gend. State Soc. 2018, 25, 521–544. [Google Scholar]

- Collings, S.J.; Griffiths, S.; Kumalo, M. Patterns of Disclosure in Child Sexual Abuse. South Afr. J. Psychol. 2005, 35, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElvaney, R. Disclosure of Child Sexual Abuse: Delays, Non-disclosure and Partial Disclosure. What the Research Tells Us and Implications for Practice. Child Abus. Rev. 2013, 24, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElvaney, R.; Greene, S.; Hogan, D. To Tell or Not to Tell? Factors Influencing Young People’s Informal Disclosures of Child Sexual Abuse. J. Interpers. Violence 2014, 29, 928–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, T.P.; Chopra, V.; Chikanya, S.R. It isn’t that we’re prostitutes: Child protection and sexual exploitation of adolescent girls within and beyond refugee camps in Rwanda. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 86, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aderinto, A. Sexual abuse of the girl-child in urban Nigeria and implications for the transmission of HIV/AIDS. Gend. Behav. 2010, 8, 2735–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Hidden in plain sight: A statistical analysis of violence against children; UNICEF: New York, USA, 2015; Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/hidden-in-plain-sight-a-statistical-analysis-of-violence-against-children (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Micaela, C.; Bascelli, E.; Paci, D.; Romito, P. Adolescents who experienced sexual abuse: Fears, needs and impediments to disclosure. Child Abus. Negl. 2004, 28, 1035–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Sable, M.R.; Danis, F.; Mauzy, D.L.; Gallagher, S.K. Barriers to reporting sexual assault for women and men: Perspectives of college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2006, 55, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceelen, M.; Dorn, T.; Van Huis, F.S.; Reijnders, U.J.L. Characteristics and Post-Decision Attitudes of Non-Reporting Sexual Violence Victims. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 34, 1961–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendy, L.; Fileborn, B.; Powell, A.; Hanley, N.; Henry, N. I Think It’s Rape and I Think He Would be Found Not Guilty’ Focus Group Perceptions of (un) Reasonable Belief in Consent in Rape Law. Soc. Leg. Stud. 2016, 25, 611–629. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, M.; Stefansen, K.; Skilbrei, M.L. Non-reporting of sexual violence as action: Acts, selves, futures in the making. Nord. J. Criminol. 2021, 22, 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hershkowitz, I.; Lanes, O.; Lamb, M.E. Exploring the disclosure of child sexual abuse with alleged victims and their parents. Child Abus. Negl. 2007, 31, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, P.; Leventhal, J.M.; Asnes, A.G. Children’s disclosures of sexual abuse: Learning from direct inquiry. Child Abus. Negl. 2011, 35, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman-Brown, T.B.; Edelstein, R.S.; Goodman, G.S.; Jones, D.P.; Gordon, D.S. Why children tell: A model of children’s disclosure of sexual abuse. Child Abus. Negl. 2003, 27, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorensen, T.; Snow, B. How children tell: The process of disclosure in child sexual abuse. Child Welf. 1991, 70, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Buss, D.; Lebert, J.; Rutherford, B.; Sharkey, D.; Aginam, O. Sexual violence in conflict and post-conflict societies. In International Agendas African Contexts; Buss, D., Lebert, J.M., Rutherford, B.A., Sharkey, D., Aginam, O., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Asal, V.; Nagel, R.U. Control over Bodies and Territories: Insurgent Territorial Control and Sexual Violence. Secur. Stud. 2021, 30, 136–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, M.; Falloon, J. Some Sydney children define abuse: Implications for agency in childhood. In Conceptualising Child-Adult Relations; Mayal, B., Alanen, L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2002; pp. 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, J. Giving voice to children’s voices: Practices and problems, pitfalls and potentials. Am. Anthropol. 2007, 109, 261–272. [Google Scholar]

- Alison, J.; Jenks, C.; Prout, A. Theorizing childhood. In Theorizing Childhood; Polity Press: Oxford, UK, 1998; pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- Mayall, B. The sociology of childhood in relation to children’s rights. Int. J. Child. Rights 2000, 8, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, J.; James, A.L. Childhood: Toward a theory of continuity and change. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2001, 575, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, G. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1986; Volume 349. [Google Scholar]

- Kumpulainen, K.; Kajamaa, A.; Rajala, A. Understanding educational change: Agency-structure dynamics in a novel design and making environment. Digit. Educ. Rev. 2018, 33, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheila, G.; Nixon, E. Children as Agents in Their Worlds: A Psychological Relational Perspective; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Priscilla, A.; Yoshida, T.; Esser, F.; Baader, M.; Betz, T.; Hungerland, B. Meanings of children’s agency. In Children as Actors: Childhood and Agency; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Clare, M. Disclosure as discourse: Theorizing children’s reports of sexual abuse. Theory Psychol. 1999, 9, 503–532. [Google Scholar]

- Staller, K.M.; Nelson-Gardell, D. “A burden in your heart”: Lessons of disclosure from female preadolescent and adolescent survivors of sexual abuse. Child Abus. Negl. 2005, 29, 1415–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElvaney, R.; Greene, S.; Hogan, D. Containing the Secret of Child Sexual Abuse. J. Interpers. Violence 2012, 27, 1155–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banwari, M. Poverty, child sexual abuse and HIV in the Transkei region, South Africa. Afr. Health Sci. 2011, 11, S117–S121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capri, C. Madness and defence: Interventions with sexually abused children in a low-income South African community. Eur. J. Psychother. Couns. 2013, 15, 32–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chishugi, J.; Franke, T. Sexual Abuse in Cameroon: A Four-Year-Old Girl Victim of Rape in Buea Case Study. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2016, 25, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, S.J. Professional services for child rape survivors: A child-centred perspective on helpful and harmful experiences. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2011, 23, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebuenyi, I.D.; Chikezie, U.E.; Dariah, G.O. Implications of Silence in the Face of Child Sexual Abuse: Observations from Yenagoa, Nigeria. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2018, 22, 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Lonnie, E.; Wachira, J.; Kamanda, A.; Naanyu, V.; Winston, S.; Ayuku, D.; Braitstein, P. Once you join the streets you will have to do it: Sexual practices of street children and youth in Uasin Gishu County, Kenya. Reprod. Health 2015, 12, 106. [Google Scholar]

- Kasherwa, A.C.; Twikirize, J.M. Ritualistic child sexual abuse in post-conflict Eastern DRC: Factors associated with the phenomenon and implications for social work. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 81, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Mat, M.L.J. Sexual violence is not good for our country’s development. Students’ interpretations of sexual violence in a secondary school in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Gend. Educ. 2016, 28, 562–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, S.; Devries, K. Local narratives of sexual and other violence against children and young people in Zanzibar. Cult. Health Sex. 2017, 20, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayeza, E.; Bhana, D.; Mulqueeny, D. Normalising violence? Girls and sexuality in a South African high school. J. Gend. Stud. 2022, 31, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, S.; Abrahams, N.; Jewkes, R. Exploring Mental Health Adjustment of Children Post Sexual Assault in South Africa. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2013, 22, 639–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathews, S.; Hendricks, N.; Abrahams, N. A Psychosocial Understanding of Child Sexual Abuse Disclosure Among Female Children in South Africa. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2016, 25, 636–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCleary-Sills, J.; Douglas, Z.; Rwehumbiza, A.; Hamisi, A.; Mabala, R. Gendered norms, sexual exploitation and adolescent pregnancy in rural Tanzania. Reprod. Health Matters 2013, 21, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulumeoderhwa, M. ‘A Girl Who Gets Pregnant or Spends the Night with a Man is No Longer a Girl’: Forced Marriage in the Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Sex. Cult. 2016, 20, 1042–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwanukuzi, C.; Nyamhanga, T. It is painful and unpleasant: Experiences of sexual violence among married adolescent girls in Shinyanga, Tanzania. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyokangi, D.; Phasha, N. Factors Contributing to Sexual Violence at Selected Schools for Learners with Mild Intellectual Disability in South Africa. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2016, 29, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phasha, N. An alternative placement as an effective measure for easing negative consequences of child sexual abuse. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 2, 5518–5522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phasha, T.N. Educational Resilience Among African Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse in South Africa. J. Black Stud. 2009, 40, 1234–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, D. Through War to Peace: Sexual Violence and Adolescent Girls. In Sexual Violence in Conflict and Post-Conflict Societies; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2014; pp. 102–114. [Google Scholar]

- Thupayagale-Tshweneagae, G.B.; Phuthi, K.; Ibitoye, O.F. Patterns and Dynamics of Sexual Violence among Married Adolescents in Zimbabwe. Afr. J. Nurs. Midwifery 2019, 21, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangamati, C.K.; Thorsen, V.C.; Gele, A.A.; Sundby, J. Postrape care services to minors in Kenya: Are the services healing or hurting survivors? Int. J. Women’s Health 2016, 8, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangamati, C.K.; Sundby, J.; Prince, R.J. Communities’ perceptions of factors contributing to child sexual abuse vulnerability in Kenya: A qualitative study. Cult. Health Sex. 2018, 20, 1394–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshodi, Y.; Macharia, M.; Lachman, A.; Seedat, S. Immediate and Long-Term Mental Health Outcomes in Adolescent Female Rape Survivors. J. Interpers. Violence 2016, 35, 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boledi, M.; Pillay, V. Shrouds of Silence: A Case Study of Sexual Abuse in Schools in the Limpopo Province in South Africa. Perspect. Educ. 2014, 32, 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Oduro, G.Y.; Swartz, S.; Arnot, M. Gender-based violence: Young women’s experiences in the slums and streets of three sub-Saharan African cities. Theory Res. Educ. 2012, 10, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breetzke, G.D.; Fabris-Rotelli, I.; Modiba, J.; Edelstein, I.S. The proximity of sexual violence to schools: Evidence from a township in South Africa. Geojournal 2021, 86, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, B. Physical and Sexual Violence Against Children in Kenya Within a Cultural Context. Community Pract. J. Community Pract. Health Visit. Assoc. 2016, 89, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Chernelle, L.; Michelle, A. An exploration of student perceptions of the risks and protective factors associated with child sexual abuse and incest in the Western Cape, South Africa. Afr. Saf. Promot. A J. Inj. Violence Prev. 2014, 12, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Women’s Refugee Commission. A Girl No More: The Changing Norms of Child Marriage in Conflict; Women’s Refugee Commission: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Seff, I.; Williams, A.; Hussain, F.; Landis, D.; Poulton, C.; Falb, K.; Stark, L. Forced Sex and Early Marriage: Understanding the Linkages and Norms in a Humanitarian Setting. Violence Women 2020, 26, 787–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bohemen, S. Doing culture and diversity justice: Using peer-to-peer ethnography in research on young people, ethnicity and sexuality. Poetics 2022, 91, 101615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alex, P.; Berge, E. How to do a systematic review. Int. J. Stroke 2018, 13, 138–156. [Google Scholar]

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence Systematic Review Software. Veritas Health Innovation. 2017. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Study Title | Country | Participants | Research Approach | Data Collection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual abuse of girl child | Nigeria |

| Qualitative research |

|

| Poverty, child sexual abuse and HIV in Transkei region, South Africa | South Africa |

| Retrospective qualitative study |

|

| Madness and Defence: interventions with sexually abused children in low-income South African community | South Africa |

| Ethnographic research | Direct observation of survivor + social worker interactions |

| Sexual abuse in Cameroon: A four-year-old girl victim of rape in Buea case study | Cameroon |

| Case study | Interaction with survivor and mother |

| Professional services for child rape survivors: child-centered perspective on helpful and harmful experiences. | South Africa |

| Qualitative research | Focused interviews |

| Implications of Silence in the Face of Child Sexual Abuse: Observations from Yenagoa, Nigeria | Nigeria |

| Case report method | Analysis of hospital sexual abuse cases |

| “Once you join the streets you will have to do it”: sexual practices of street children and youth in Uasin Gishu County, Kenya | Kenya |

| Qualitative research | In-depth interviews and FGDs |

| Ritualistic child sexual abuse in post-conflict Eastern DRC: Factors associated with phenomenon and implications for social work | Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) |

| Exploratory qualitative study | Unstructured interviews and FGDs |

| “Sexual violence is not good for our country’s development”. Students’ interpretations of sexual violence in a secondary school in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia | Ethiopia |

| Qualitative research |

|

| Local narratives of sexual and other violence against children and young people in Zanzibar | Tanzania |

| Qualitative research | In-depth interviews and FGDs |

| Normalizing violence? Girls and sexuality in a South African high school | South Africa |

| Qualitative research |

FGDs, in-depth interviews |

| Exploring Mental Health Adjustment of Children Post Sexual Assault in South Africa | South Africa |

| Grounded theory | In-depth, semi-structured interviews |

| A Psychosocial Understanding of Child Sexual Abuse Disclosure Among Female Children in South Africa | South Africa |

| Grounded theory | In-depth, semi-structured interviews |

| Gendered norms, sexual exploitation and adolescent pregnancy in rural Tanzania | Tanzania |

| Qualitative research | Participatory learning and action (PLA) activities |

| ‘A girl who gets pregnant or spends the night with a man is no longer a girl’: Forced marriage in the Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo | DRC |

| Qualitative research | FGDs and individual interviews |

| ‘It is painful and unpleasant’: experiences of sexual violence among married adolescent girls in Shinyanga, Tanzania | Tanzania | Married girls aged 12–17 | Phenomenology | In-depth interviews |

| Child Sexual Abuse and Situational Context: Children’s Experiences in Post-conflict Northern Uganda. | Uganda | 43 children aged 6–17 | Qualitative research | Individual interviews |

| Factors Contributing to Sexual Violence at Selected Schools for Learners with Mild Intellectual Disability in South Africa | South Africa |

| Multiple-case research design | Interviews with learners, school nurse and social worker |

| An alternative placement as an effective measure for easing negative consequences of child sexual abuse | South Africa |

| Qualitative research |

|

| Educational Resilience Among African Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse in South Africa | South Africa |

| Qualitative research |

|

| Through War to Peace: Sexual Violence & Adolescent Girls. in Sexual Violence in Conflict & Post-conflict Societies | Sierra Leone |

| Qualitative research | Observations and interviews |

| Patterns & dynamics of sexual violence among married adolescents in Zimbabwe | Zimbabwe |

| Qualitative research | Semi-structured interviews |

| Post-rape care services to minors in Kenya: are the services healing or hurting survivors? | Kenya | Two case studies | Qualitative research |

|

| Communities’ perceptions of factors contributing to child sexual abuse vulnerability in Kenya: a qualitative study | Kenya |

| Qualitative research | FGDs |

| ‘It isn’t that we’re prostitutes’: Child protection & sexual exploitation of adolescent girls within & beyond refugee camps in Rwanda | Rwanda |

| Qualitative research |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kakuru, D. Choice of Non-Disclosure as Agency: A Systematic Review of Non-Disclosure of Sexual Violence in Girlhood in Africa. Women 2023, 3, 322-334. https://doi.org/10.3390/women3020024

Kakuru D. Choice of Non-Disclosure as Agency: A Systematic Review of Non-Disclosure of Sexual Violence in Girlhood in Africa. Women. 2023; 3(2):322-334. https://doi.org/10.3390/women3020024

Chicago/Turabian StyleKakuru, Doris. 2023. "Choice of Non-Disclosure as Agency: A Systematic Review of Non-Disclosure of Sexual Violence in Girlhood in Africa" Women 3, no. 2: 322-334. https://doi.org/10.3390/women3020024

APA StyleKakuru, D. (2023). Choice of Non-Disclosure as Agency: A Systematic Review of Non-Disclosure of Sexual Violence in Girlhood in Africa. Women, 3(2), 322-334. https://doi.org/10.3390/women3020024