Early Marriage in Adolescence and Risk of High Blood Pressure and High Blood Glucose in Adulthood: Evidence from India

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

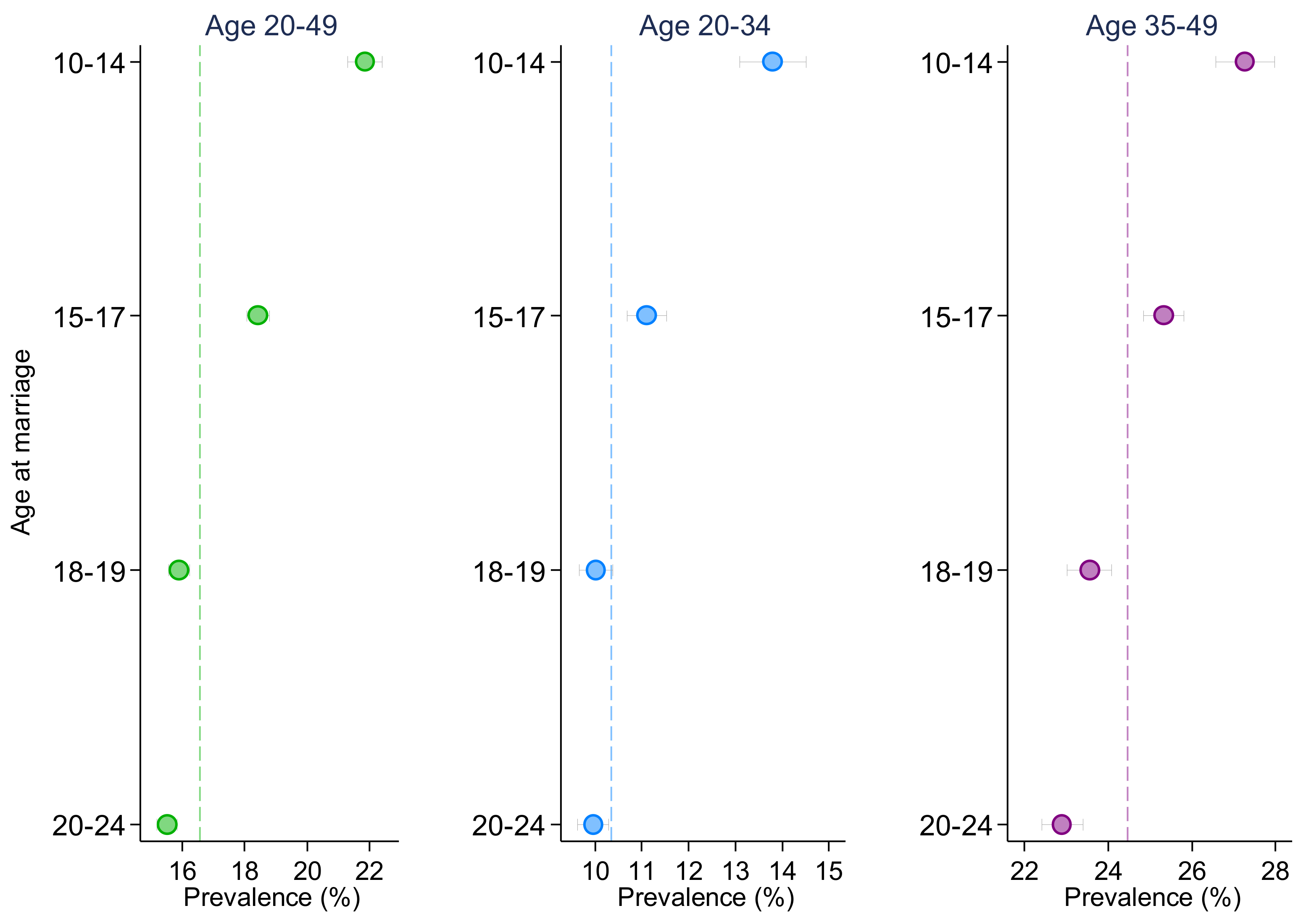

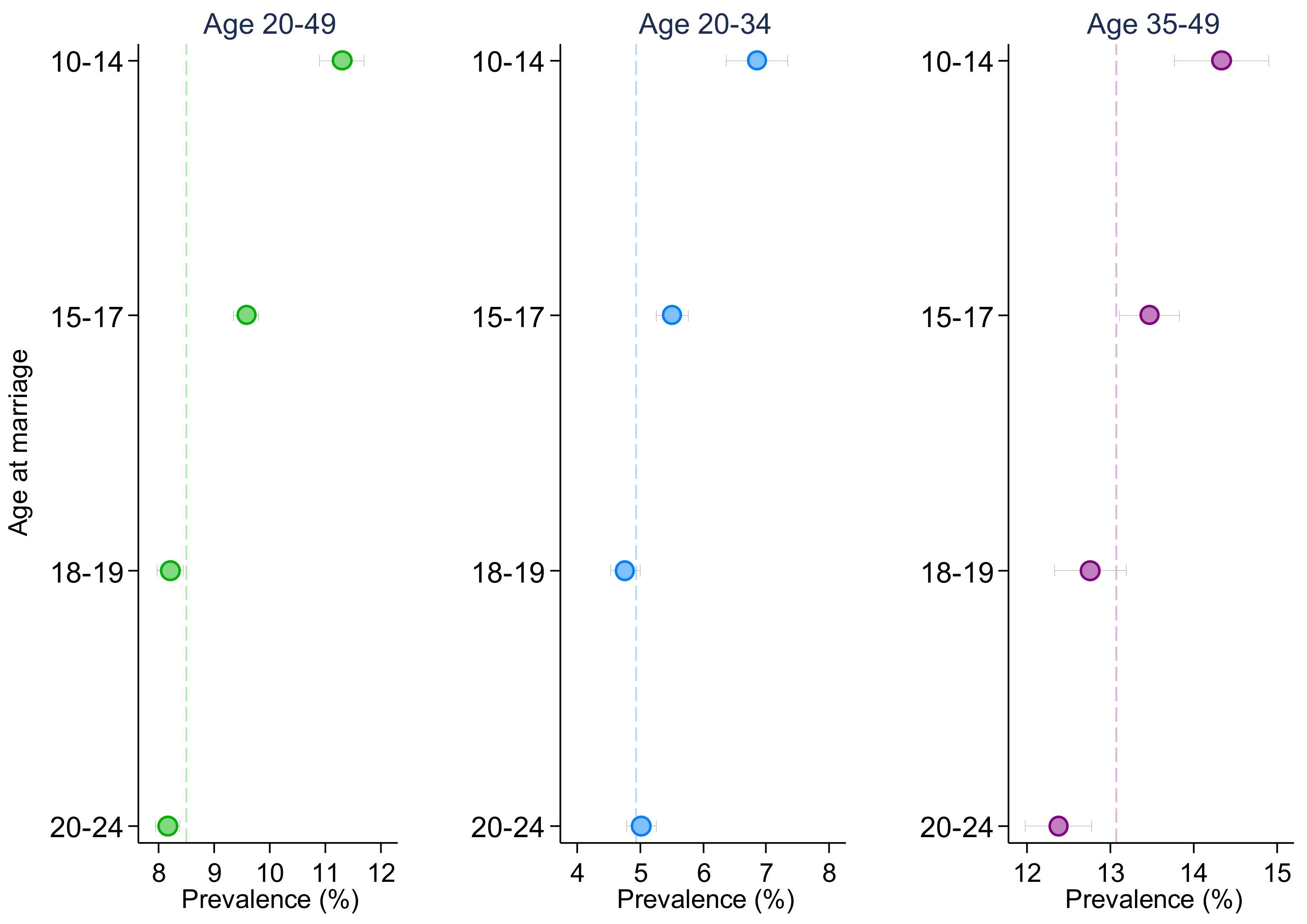

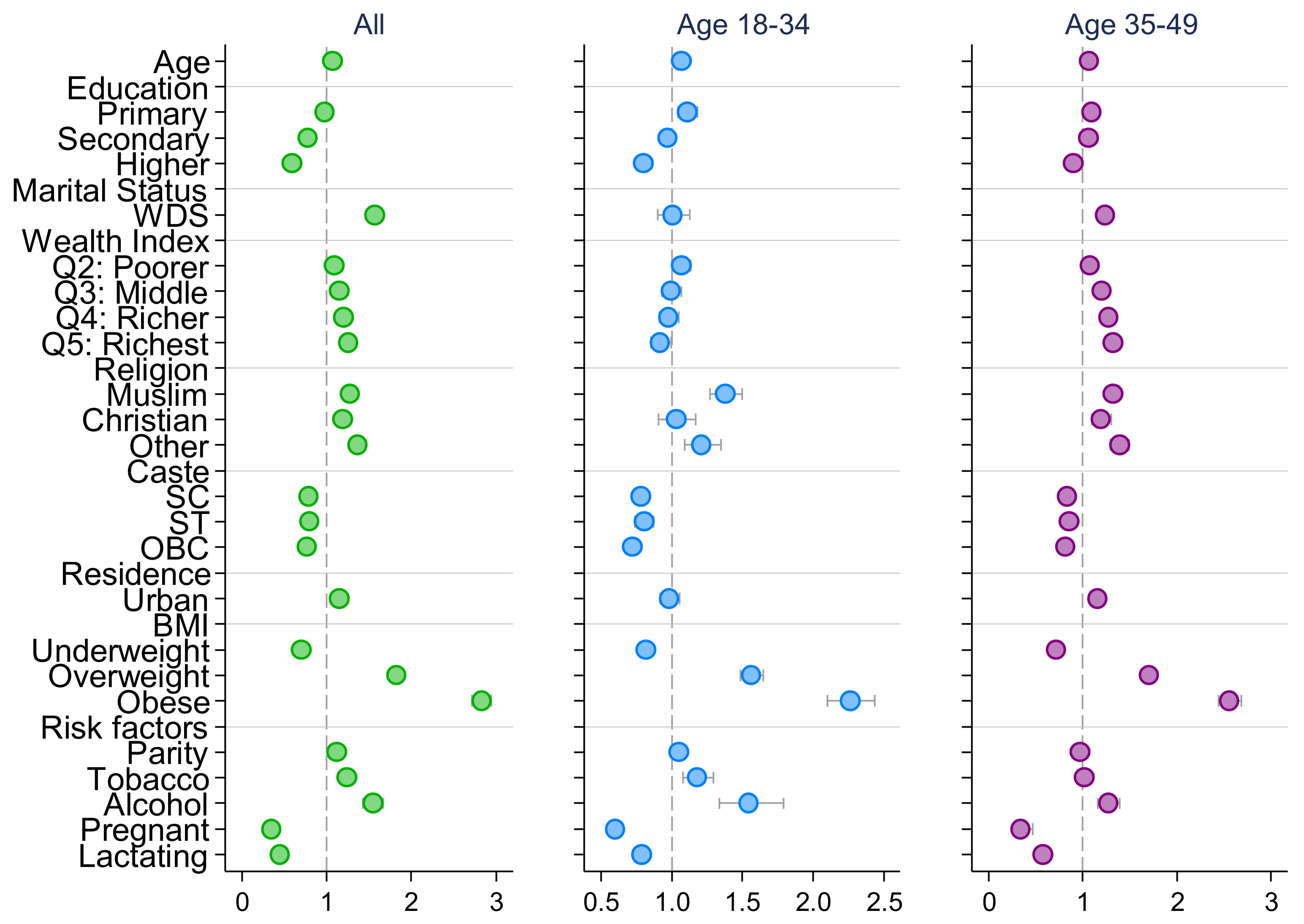

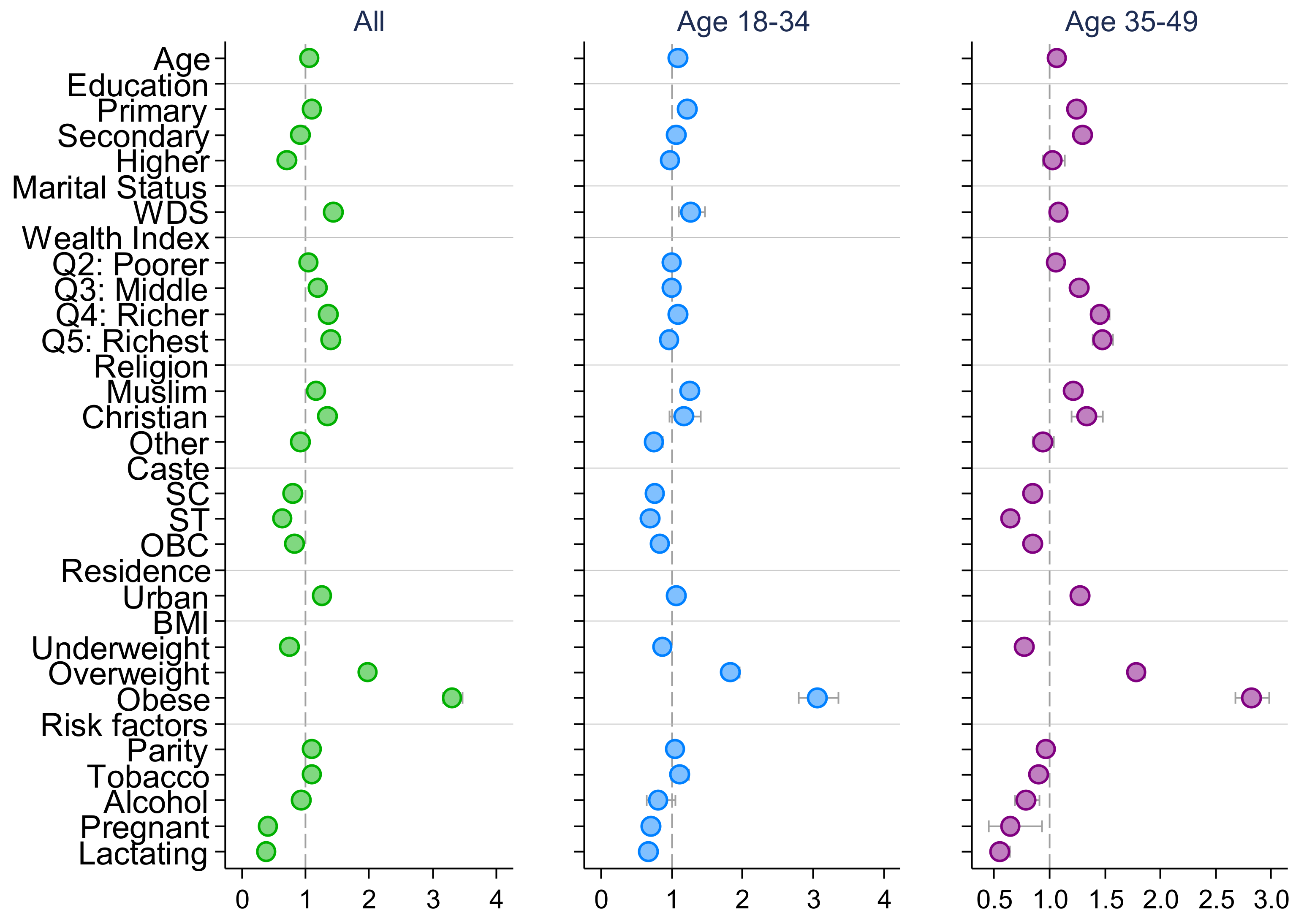

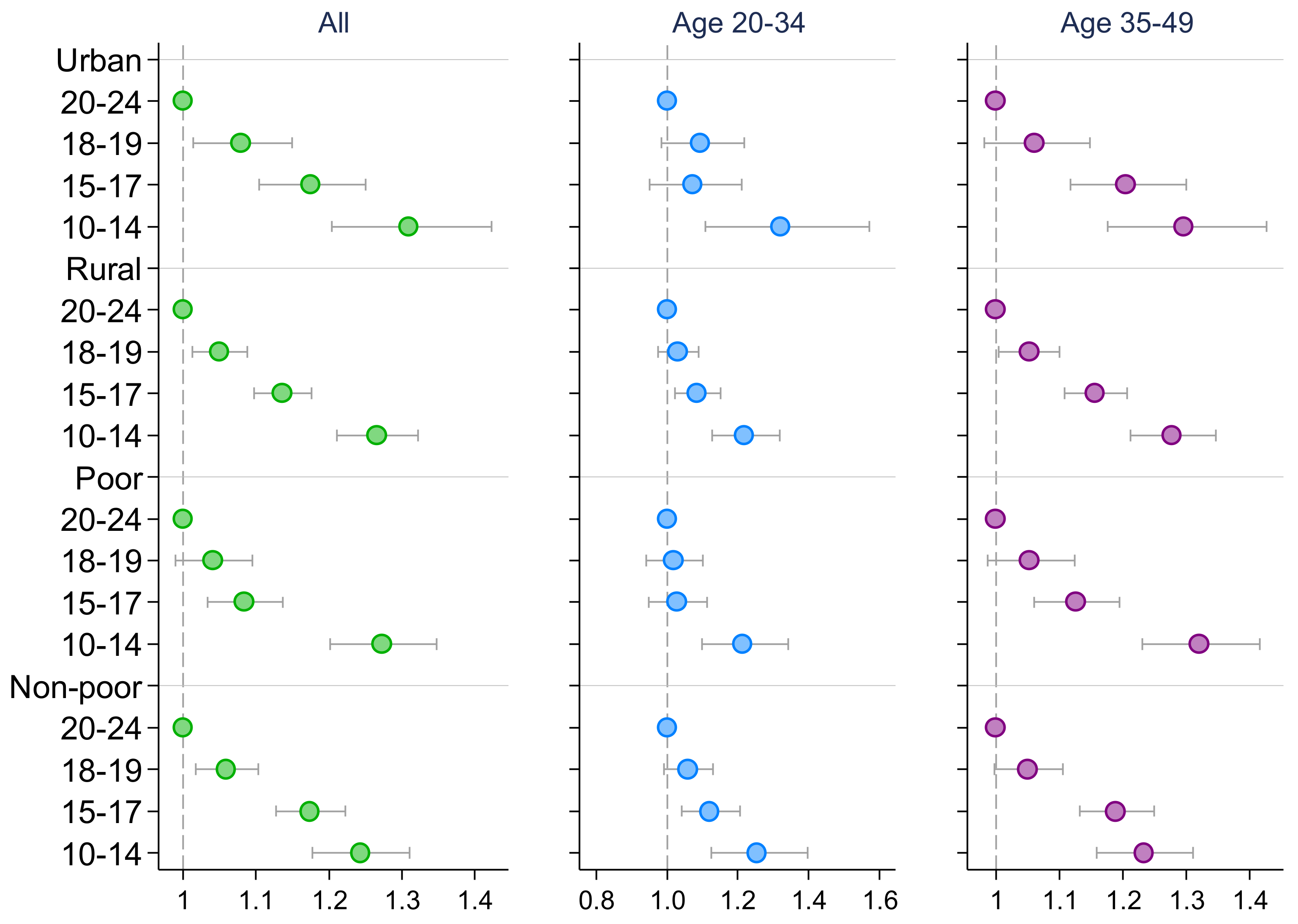

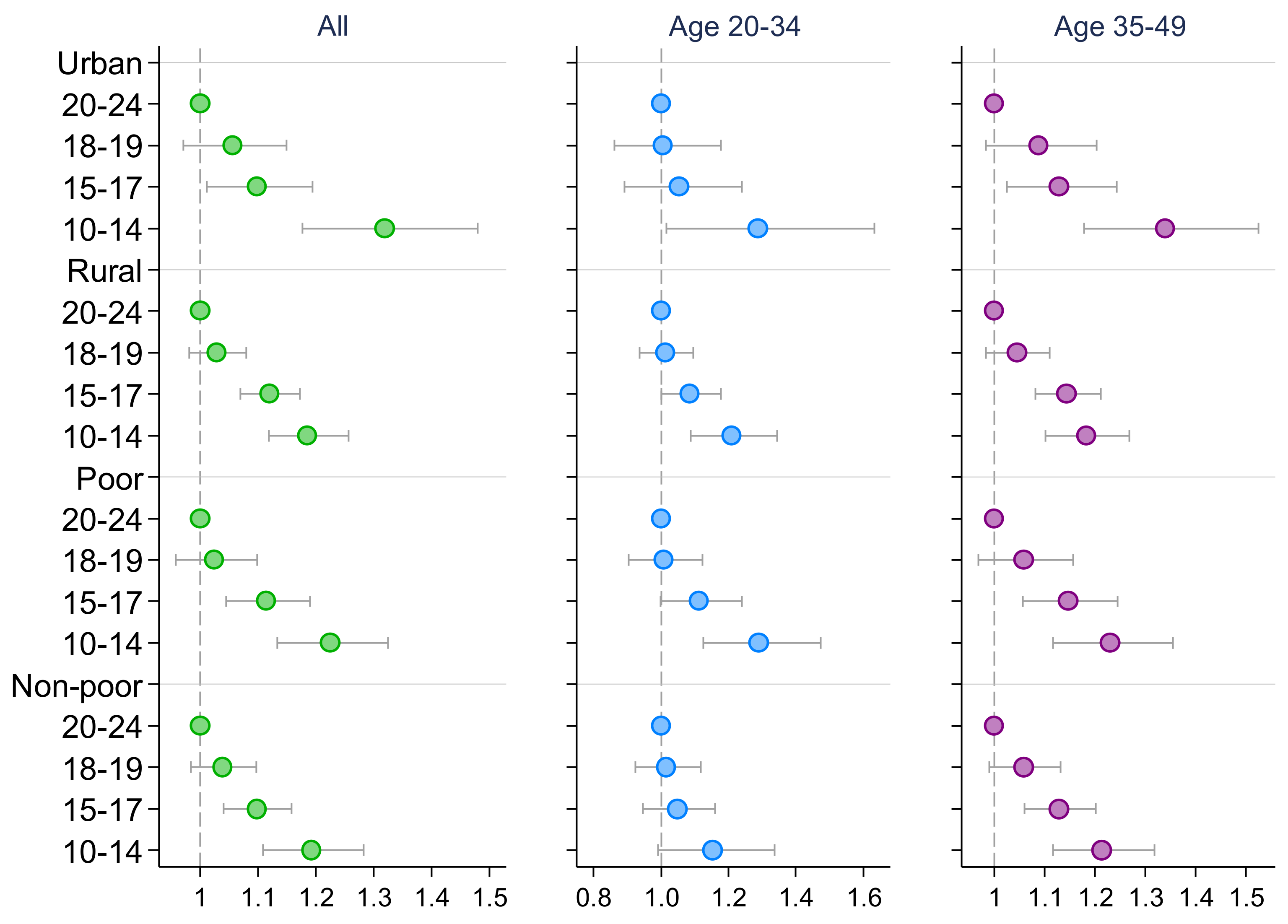

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Health. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Eiland, L.; Romeo, R.D. Stress and the Developing Adolescent Brain. Neuroscience 2013, 249, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fagundes, C.P.; Way, B. Early-Life Stress and Adult Inflammation. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 23, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.E.; Chen, E.; Parker, K.J. Psychological Stress in Childhood and Susceptibility to the Chronic Diseases of Aging: Moving toward a Model of Behavioral and Biological Mechanisms. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 959–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Orientation Programme on Adolescent Health for Health Care Providers. 2006. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42868 (accessed on 19 May 2022).

- United Nations Population Fund. Child Marriage. 2021. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/child-marriage#readmore-expand (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Abera, M.; Nega, A.; Tefera, Y.; Gelagay, A.A. Early Marriage and Women’s Empowerment: The Case of Child-Brides in Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2020, 20, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Strat, Y.; Dubertret, C.; Le Foll, B. Child Marriage in the United States and Its Association with Mental Health in Women. Pediatrics 2011, 128, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- John, N.A.; Edmeades, J.; Murithi, L. Child Marriage and Psychological Well-Being in Niger and Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hampton, T. Child Marriage Threatens Girls’ Health. JAMA 2010, 304, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilenko, S.A.; Kugler, K.C.; Rice, C.E. Timing of First Sexual Intercourse and Young Adult Health Outcomes. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindert, J.; von Ehrenstein, O.S.; Grashow, R.; Gal, G.; Braehler, E.; Weisskopf, M.G. Sexual and Physical Abuse in Childhood Is Associated with Depression and Anxiety over the Life Course: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Public Health 2014, 59, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Towards Ending Child Marriage: Global Trends and Profiles of Progress. 2021. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/towards-ending-child-marriage/ (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Fan, S.; Koski, A. The Health Consequences of Child Marriage: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, B.; Tiwari, A. Adding to Her Woes: Child Bride’s Higher Risk of Hypertension at Young Adulthood. J. Public Health 2022, fdac026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, B.; Tiwari, A.; Glenn, L. Stolen Childhood Taking a Toll at Young Adulthood: The Higher Risk of High Blood Pressure and High Blood Glucose Comorbidity among Child Brides. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0000638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikram, K. Early Marriage and Health among Women at Midlife: Evidence from India. J. Marriage Fam. 2021, 83, 1480–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. Empowering Adolescent Girls and Boys in India. 2022. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/india/what-we-do/adolescent-development-participation (accessed on 19 May 2022).

- International Institute for Population Sciences; ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019–2021. 2021. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR375/FR375.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Prenissl, J.; Manne-Goehler, J.; Jaacks, L.M.; Prabhakaran, D.; Awasthi, A.; Bischops, A.C.; Atun, R.; Bärnighausen, T.; Davies, J.I.; Vollmer, S.; et al. Hypertension Screening, Awareness, Treatment, and Control in India: A Nationally Representative Cross-Sectional Study among Individuals Aged 15 to 49 Years. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, P.; Shil, A.; Shetty, A.; Dhar, B.; Singh, S.K.; Pati, S.; Billah, B. Contribution of Modifiable Risk Factors on the Burden of Diabetes among Women in Reproductive Age-Group in India: A Population Based Cross-Sectional Study. J. Public Health Policy 2022, 43, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, M.; Zayeri, F.; Salehi, M. Trend Analysis of Cardiovascular Disease Mortality, Incidence, and Mortality-to-Incidence Ratio: Results from Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruccelli, K.; Davis, J.; Berman, T. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Associated Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 97, 104127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickrama, K.A.S.; Lee, T.-K.; O’Neal, C.W. Stressful Life Experiences in Adolescence and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Young Adulthood. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, B.K.; Tiwari, A.; Fazlul, I. Child Marriage and Risky Health Behaviors: An Analysis of Tobacco Use among Early Adult and Early Middle-Aged Women in India. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remsberg, K.E.; Demerath, E.W.; Schubert, C.M.; Chumlea, W.C.; Sun, S.S.; Siervogel, R.M. Early Menarche and the Development of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in Adolescent Girls: The Fels Longitudinal Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 2718–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elks, C.E.; Ong, K.K.; Scott, R.A.; van der Schouw, Y.T.; Brand, J.S.; Wark, P.A.; Amiano, P.; Balkau, B.; Barricarte, A.; Boeing, H.; et al. The InterAct Consortium. Age at Menarche and Type 2 Diabetes Risk. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 3526–3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ibitoye, M.; Choi, C.; Tai, H.; Lee, G.; Sommer, M. Early Menarche: A Systematic Review of Its Effect on Sexual and Reproductive Health in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Islam, M.A.; Rahman, A. Age at First Marriage and Fertility in Developing Countries: A Meta Analytical View of 15 Demographic and Health Surveys. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 8, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Datta, B.K.; Husain, M.J.; Kostova, D. Hypertension in Women: The Role of Adolescent Childbearing. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Saggurti, N.; Balaiah, D.; Silverman, J.G. Prevalence of Child Marriage and Its Effect on Fertility and Fertility-Control Outcomes of Young Women in India: A Cross-Sectional, Observational Study. Lancet 2009, 373, 1883–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Psaki, S.R.; Melnikas, A.J.; Haque, E.; Saul, G.; Misunas, C.; Patel, S.K.; Ngo, T.; Amin, S. What Are the Drivers of Child Marriage? A Conceptual Framework to Guide Policies and Programs. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 69, S13–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitila, S.B.; Terfa, Y.B.; Akuma, A.O.; Olika, A.K.; Olika, A.K. Spousal Age Difference and Its Effect on Contraceptive Use among Sexually Active Couples in Ethiopia: Evidence from the 2016 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey. Contracept. Reprod. Med. 2020, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, E.; Read, S. Pathways from Fertility History to Later Life Health: Results from Analyses of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Demogr. Res. 2015, 32, 107–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yim, I.S.; Kofman, Y.B. The Psychobiology of Stress and Intimate Partner Violence. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 105, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Gaur, K.; Ram, C.V.S. Emerging Trends in Hypertension Epidemiology in India. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2019, 33, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chockalingam, A.; Ganesan, N.; Venkatesan, S.; Gnanavelu, G.; Subramaniam, T.; Jaganathan, V.; Elangovan, S.; Alagesan, R.; Dorairajan, S.; Subramaniam, A.; et al. Patterns and Predictors of Prehypertension Among “Healthy” Urban Adults in India. Angiology 2005, 56, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oruganti, A.; Kavi, A.; Walvekar, P. Risk of Developing Diabetes Mellitus among Urban Poor South Indian Population Using Indian Diabetes Risk Score. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, A.; Snehalatha, C.; Kapur, A.; Vijay, V.; Mohan, V.; Das, A.K.; Rao, P.V.; Yajnik, C.S.; Prasanna Kumar, K.M.; Nair, J.D. High Prevalence of Diabetes and Impaired Glucose Tolerance in India: National Urban Diabetes Survey. Diabetologia 2001, 44, 1094–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ever Married | Married at Adolescence | Married at Youth: 20–24 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early: 10–14 | Middle: 15–17 | Late: 18–19 | |||

| Percentage of women 1 | |||||

| Categorial covariates | |||||

| Education | |||||

| No education | 30.06 | 50.07 | 36.94 | 26.16 | 17.78 |

| (45.85) | (47.95) | (47.28) | (44.30) | (39.40) | |

| Primary | 14.90 | 21.1 | 17.93 | 14.27 | 9.69 |

| (35.61) | (39.13) | (37.58) | (35.26) | (30.49) | |

| Secondary | 44.86 | 27.75 | 42.51 | 51.71 | 48.91 |

| (49.73) | (42.94) | (48.43) | (50.37) | (51.52) | |

| Higher | 10.19 | 1.09 | 2.62 | 7.86 | 23.62 |

| (30.25) | (9.95) | (15.64) | (27.12) | (43.77) | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 94.34 | 91.60 | 93.82 | 95.01 | 95.47 |

| (23.11) | (26.60) | (23.6) | (21.95) | (21.43) | |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 5.66 | 8.40 | 6.18 | 4.99 | 4.53 |

| (23.11) | (26.60) | (23.60) | (21.95) | (21.43) | |

| Wealth index quintile | |||||

| 1st (Poorest) | 19.55 | 26.96 | 23.57 | 18.73 | 13.00 |

| (39.66) | (42.56) | (41.58) | (39.33) | (34.66) | |

| 2nd (Poorer) | 20.86 | 25.42 | 23.74 | 20.9 | 15.98 |

| (40.63) | (41.76) | (41.68) | (40.98) | (37.76) | |

| 3rd (Middle) | 21.12 | 22.35 | 22.06 | 21.79 | 19.10 |

| (40.81) | (39.95) | (40.62) | (41.61) | (40.51) | |

| 4th (Richer) | 20.67 | 16.79 | 18.72 | 21.31 | 23.79 |

| (40.50) | (35.84) | (38.21) | (41.28) | (43.89) | |

| 5th (Richest) | 17.79 | 8.48 | 11.92 | 17.27 | 28.13 |

| (38.24) | (26.71) | (31.74) | (38.1) | (46.34) | |

| Religion | |||||

| Hindu | 82.66 | 82.48 | 83.48 | 82.91 | 81.68 |

| (37.86) | (36.45) | (36.38) | (37.94) | (39.87) | |

| Muslim | 12.83 | 14.29 | 13.13 | 12.80 | 11.93 |

| (33.44) | (33.57) | (33.09) | (33.68) | (33.41) | |

| Christian | 2.01 | 1.74 | 1.49 | 1.80 | 2.82 |

| (14.03) | (12.54) | (11.86) | (13.41) | (17.06) | |

| Other | 2.50 | 1.48 | 1.90 | 2.48 | 3.57 |

| (15.63) | (11.58) | (13.37) | (15.68) | (19.13) | |

| Caste | |||||

| None | 25.07 | 23.14 | 23.48 | 23.98 | 28.36 |

| (43.34) | (40.45) | (41.53) | (43.03) | (46.46) | |

| Scheduled caste | 22.10 | 25.88 | 23.59 | 21.63 | 19.38 |

| (41.49) | (42.00) | (41.59) | (41.50) | (40.74) | |

| Scheduled tribe | 9.42 | 9.76 | 10.04 | 9.67 | 8.45 |

| (29.21) | (28.46) | (29.44) | (29.79) | (28.66) | |

| Other backward class | 43.41 | 41.22 | 42.89 | 44.72 | 43.81 |

| (49.56) | (47.21) | (48.49) | (50.12) | (51.13) | |

| Residence | |||||

| Rural | 70.26 | 77.21 | 74.87 | 70.88 | 62.15 |

| (45.71) | (40.23) | (42.5) | (45.79) | (49.99) | |

| Urban | 29.74 | 22.79 | 25.13 | 29.12 | 37.85 |

| (45.71) | (40.23) | (42.5) | (45.79) | (49.99) | |

| BMI group | |||||

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 57.91 | 57.4 | 58.48 | 58.54 | 57.03 |

| (49.37) | (47.42) | (48.28) | (49.66) | (51.02) | |

| Thin (<18.5) | 13.40 | 13.89 | 13.85 | 14.27 | 12.05 |

| (34.07) | (33.17) | (33.84) | (35.25) | (33.56) | |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 21.05 | 21.32 | 20.23 | 20.13 | 22.50 |

| (40.76) | (39.28) | (39.36) | (40.42) | (43.04) | |

| Obese (≥30.0) | 7.64 | 7.39 | 7.44 | 7.06 | 8.42 |

| (26.57) | (25.09) | (25.71) | (25.81) | (28.62) | |

| Tobacco use | 5.41 | 8.11 | 6.48 | 4.87 | 3.61 |

| (22.62) | (26.18) | (24.12) | (21.69) | (19.24) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.88 | 1.39 | 0.94 | 0.74 | 0.73 |

| (9.36) | (11.24) | (9.45) | (8.65) | (8.77) | |

| Pregnant | 4.31 | 1.43 | 3.01 | 5.05 | 6.27 |

| (20.31) | (11.4) | (16.73) | (22.06) | (24.98) | |

| Lactating | 18.56 | 8.66 | 16.03 | 22.45 | 22.18 |

| (38.88) | (26.97) | (35.95) | (42.06) | (8.30) | |

| Continuous covariates | |||||

| Years | |||||

| Age | 34.1 | 36.23 | 34.59 | 33.09 | 33.5 |

| (8.31) | (7.43) | (8.17) | (8.67) | (42.82) | |

| Number | |||||

| Parity | 2.43 | 3.12 | 2.77 | 2.32 | 1.89 |

| (1.46) | (1.50) | (1.43) | (1.39) | (1.32) | |

| Observations | 466,693 | 54,943 | 142,309 | 116,589 | 152,852 |

| High Blood Pressure 1 | High Blood Glucose | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Age 20–34 | Age 35–49 | All | Age 20–34 | Age 35–49 | |

| Age at marriage | ||||||

| Youth (20–24) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Early adolescence (10–14) | 1.521 *** | 1.446 *** | 1.262 *** | 1.432 *** | 1.393 *** | 1.184 *** |

| (1.466, 1.578) | (1.355, 1.543) | (1.208, 1.318) | (1.364, 1.504) | (1.274, 1.523) | (1.116, 1.255) | |

| Middle adolescence (15–17) | 1.229 *** | 1.129 *** | 1.142 *** | 1.192 *** | 1.101 ** | 1.101 *** |

| (1.194, 1.266) | (1.073, 1.188) | (1.101, 1.183) | (1.147, 1.238) | (1.031, 1.176) | (1.050, 1.155) | |

| Late adolescence (18–19) | 1.029 | 1.006 | 1.037 | 1.006 | 0.945 | 1.035 |

| (0.998, 1.061) | (0.959, 1.056) | (0.997, 1.079) | (0.966, 1.049) | (0.882, 1.013) | (0.981, 1.091) | |

| Observations | 466,693 | 242,201 | 224,492 | 459,816 | 239,711 | 220,105 |

| High Blood Pressure 1 | High Blood Glucose | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Age 20–34 | Age 35–49 | All | Age 20–34 | Age 35–49 | |

| Age at marriage | ||||||

| Youth (20–24) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Early adolescence (10–14) | 1.288 *** | 1.249 *** | 1.292 *** | 1.227 *** | 1.224 *** | 1.233 *** |

| (1.239, 1.340) | (1.162, 1.343) | (1.233, 1.354) | (1.163, 1.295) | (1.108, 1.352) | (1.157, 1.314) | |

| Middle adolescence (15–17) | 1.155 *** | 1.085 ** | 1.178 *** | 1.120 *** | 1.078 * | 1.145 *** |

| (1.120, 1.192) | (1.027, 1.147) | (1.133, 1.224) | (1.075, 1.168) | (1.000, 1.161) | (1.089, 1.205) | |

| Late adolescence (18–19) | 1.063 *** | 1.049 | 1.058 ** | 1.042 | 1.013 | 1.063 * |

| (1.030, 1.097) | (0.997, 1.103) | (1.016, 1.102) | (0.998, 1.088) | (0.942, 1.089) | (1.007, 1.122) | |

| Observations | 465,575 | 241,687 | 223,888 | 458,777 | 239,229 | 219,548 |

| High Blood Pressure 1 | High Blood Glucose | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Age 20–34 | Age 35–49 | All | Age 20–34 | Age 35–49 | |

| Age at marriage | ||||||

| Youth (20–24) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Early adolescence (10–14) | 1.139 *** | 1.163 ** | 1.125 *** | 1.104 * | 1.223 ** | 1.060 |

| (1.076, 1.205) | (1.050, 1.288) | (1.051, 1.204) | (1.022, 1.194) | (1.057, 1.415) | (0.967, 1.161) | |

| Middle adolescence (15–17) | 1.066 ** | 1.038 | 1.078 ** | 1.047 | 1.150 * | 1.008 |

| (1.020, 1.113) | (0.961, 1.120) | (1.022, 1.136) | (0.986, 1.111) | (1.031, 1.282) | (0.940, 1.082) | |

| Late adolescence (18–19) | 1.026 | 1.010 | 1.029 | 1.019 | 1.064 | 1.004 |

| (0.989, 1.064) | (0.953, 1.071) | (0.981, 1.079) | (0.968, 1.072) | (0.978, 1.158) | (0.943, 1.069) | |

| Observations | 379,447 | 195,879 | 183,568 | 374,133 | 194,008 | 180,125 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Datta, B.; Tiwari, A. Early Marriage in Adolescence and Risk of High Blood Pressure and High Blood Glucose in Adulthood: Evidence from India. Women 2022, 2, 189-203. https://doi.org/10.3390/women2030020

Datta B, Tiwari A. Early Marriage in Adolescence and Risk of High Blood Pressure and High Blood Glucose in Adulthood: Evidence from India. Women. 2022; 2(3):189-203. https://doi.org/10.3390/women2030020

Chicago/Turabian StyleDatta, Biplab, and Ashwini Tiwari. 2022. "Early Marriage in Adolescence and Risk of High Blood Pressure and High Blood Glucose in Adulthood: Evidence from India" Women 2, no. 3: 189-203. https://doi.org/10.3390/women2030020

APA StyleDatta, B., & Tiwari, A. (2022). Early Marriage in Adolescence and Risk of High Blood Pressure and High Blood Glucose in Adulthood: Evidence from India. Women, 2(3), 189-203. https://doi.org/10.3390/women2030020