Abstract

As women age, they typically experience a progressive decrease in skeletal muscle mass and strength, which can lead to a decline in functional fitness and quality of life. Resistance training (RT) has the potential to attenuate these losses. Although well established for men, evidence regarding the benefits of RT for women is sparse and inconsistent: prior reviews include too few studies with women and do not adequately examine the interactive or additive impacts of workload, modalities, and nutritional supplements on outcomes such as muscle mass (MM), body composition (BC), muscle strength (MS), and functional fitness (FF). The purpose of this review is to identify these gaps. Thirty-eight papers published between 2010 and 2020 (in English) represent 2519 subjects (mean age = 66.89 ± 4.91 years). Intervention averages include 2 to 3 × 50 min sessions across 15 weeks with 7 exercises per session and 11 repetitions per set. Twelve studies (32%) examined the impact of RT plus dietary manipulation. MM, MS, and FF showed positive changes after RT. Adding RT to fitness regimens for peri- to postmenopausal women is likely to have positive benefits.

1. Introduction

Aging is typically accompanied by a progressive decrease in skeletal muscle mass (sarcopenia) and strength, which leads to a decrement in functional fitness and activities of daily living [1]. Compared to men, women typically have more frequent and severe problems with sarcopenia, functional capacity, frailty and disability [2]. Causes of muscle and bone mass and strength in women are multi-factorial, and include a loss of estrogen and physical inactivity.

Estrogen has wide-ranging physiological effects—from reproduction, to preventing vascular inflammation to helping with bone integrity—and it has an impact on metabolism due to the fact that estrogen receptors are found in bone, tendons, ligaments and muscles. In addition, estrogen has an anabolic effect on building these tissues [3]. Estrogen plays a major role in the formation of connective tissue changes in response to physical activity involving mechanical forces (e.g., resistance training) [4]. Therefore, some researchers have concluded that a loss of estrogen is likely a significant contributor for age-related decreases in muscle mass, muscle quality and strength [5,6,7].

Physical inactivity is a second major contributor to a loss of muscle and bone mass, quality, and strength [8]. As women age, they typically become less active. The good news is that physical activity is a modifiable, non-pharmacological treatment for muscle and bone loss [9].

Resistance training (RT) is a documented physical activity strategy that can be used to combat some of the deleterious effects of aging and menopause on muscle mass and strength. Resistance training consists of free weights (e.g., dumbbells, barbells, and kettlebells), medicine balls or sandbags, weight machines, elastic bands, TRX straps, and even one’s body weight.

While the majority of studies have established the benefit of RT on body composition, strength and functional fitness in men [10,11], information on the positive impact of RT is inconclusive in women. To date, reviews have examined the impact of exercise in postmenopausal women based on combined training (aerobic + resistance training) [12], whole-body vibration training [13] and high-intensity interval training (HIIT) training [14]. Marin-Cascales et al. synthesized 15 studies that examined the impact of combined training in older women [12]. Results varied based on participant age, region trained and variance in training routine. They concluded that combining RT and weight-bearing or aerobic exercise can prevent muscle and skeletal loss in women as they age, but that results were inconsistent. They also called for additional examination and comparison of various training loads and intensities on muscle composition and strength. None of the reviews to date have examined the literature relative to beneficial changes based on workload, RT modality or dietary manipulation solely in women. For example, one recent meta-analysis that included 10 studies examined the effect of creatine supplementation during RT in older adults [15]. Data were not disaggregated by sex, and only 2/10 (20%) of the studies were conducted exclusively with women. These researchers concluded that compared to RT alone, creatine plus RT increased fat-free mass (FFM), 1 repetition maximum (RM) chest press, and 1RM leg press.

Thomas et al. conducted a systematic review of the impact of adding protein supplementation to RT in older adults [16]. In their sample, 68% of the subjects were female and 32% were male, but results were not disaggregated by sex. They concluded that protein supplementation did not augment the effects of RT except for some measures of muscle strength found in 3/15 (20%) of the studies. They also mentioned that differences in protein dosage, timing, and ingestion frequency may have impacted the results. Liao et al., who also combined men and women in a systematic review and meta-analysis, concluded that adding protein to RT resulted in greater lean mass and leg strength gains than RT alone (standard mean differences of 0.58 and 0.69, respectively), and that gains in lean mass and leg strength were greater in those with a BMI ≥ 30 kg·m−2 than in those with a BMI < 30 kg·m−2 (standard mean difference of 0.53 and 0.88, respectively [17].

Given inconclusive findings to date and the lack of a review examining the impacts of RT on older women, the purpose of this paper is to review the literature on the impact of RT on body composition (BC), muscle strength (MS), and functional fitness (FF) in older women. A secondary aim is to quantify workload and summarize RT modalities and nutritional manipulations in the literature. A third aim is to identify potential gaps to guide future research. We chose to limit our review to the most recent publications (2010–2020) with healthy populations to provide an updated and focused review on this topic.

2. Materials and Methods

The 2015 version of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) checklist was utilized to ensure that recommended items were addressed in this systematic review [18]. Specifically, this review verifies eligibility criteria, information sources, search strategy, data management strategy, study selection process, data and data collection processes, outcomes included, and data synthesis. Per PRISMA instructions, we also provide a synthesis of the quality of existing studies, using PEDro [19].

2.1. Research Questions

Our primary research questions were: What are the characteristics and dosages of exercise programs? (e.g., length in weeks, times per week, sets/repetitions/number of exercises, nutritional manipulations, and RT modality) and what can be concluded about this body of literature in terms of effects on body composition, muscle strength, and functional fitness? Secondary questions were: What is the quantity and quality of the literature in this area? Who has been included in these studies (age, ethnicity, number of subjects)? What are some of the limitations and future research directions in this area?

2.2. Literature Search

2.2.1. Search Strategy

A rigorous literature search was conducted to identify papers relevant to our research topic. Table 1 contains a list of the databases searched and Boolean connectors utilized. An advanced search process was utilized to limit publications to peer-reviewed journal articles in English, published between 2010 and 2020. This publication period was selected because there was a significant increase in literature published on this topic after 2010, and topics studied have become more advanced. After the aforementioned search, additional papers were generated by searching reference lists and PubMed links to “similar articles.” Articles that combined resistance training with other types of exercise (e.g., aerobic activity, stretching activities) were not included due to the potential difficulty interpreting the unique effects of resistance training compared to other types of training. In addition, studies that examined acute effects of resistance training were not included.

Table 1.

Sample search string used for this study.

2.3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes and study design (PICOS) criteria were used to determine which papers should be included in this study [20]. Table 2 contains the PICOS criteria we utilized to determine study inclusion.

Table 2.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for selecting the studies based on PICOS criteria.

2.3.3. Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of each study was assessed using the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale, a rating scale for randomized controlled trials consisting of 11 criteria (PS) [19]. A score of 6 or higher (on a 9-point scale) indicated that the study was of medium to high quality.

3. Results

3.1. Summary of Search Results

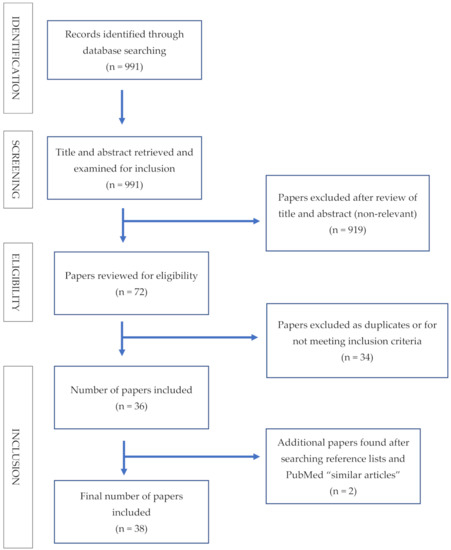

The database searches generated 991 records. Titles and abstracts were independently screened for the inclusion and exclusion criteria and 919 papers were removed, leaving 72 papers to be reviewed for eligibility. Of the 72 papers reviewed, 34 did not meet inclusion criteria, and 2 were removed as duplicates, leaving 36 papers. From the remaining 36 papers, reference lists were scanned for additional studies, and “similar articles” were searched in PubMed. As a result of these expanded search strategies, 2 additional resources were added, resulting in a total of 38 papers. A summary of the decision trail used to locate and select studies for this paper is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Search strategy and decision trail for selecting included studies.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

Table 3 presents an overall summary table for the 38 papers reviewed. Included in the table are author(s) and years, study purpose, participant description, methods, and results. Information about workload (e.g., sets, reps, number of exercises, total sessions and minutes) and outcomes assessed (e.g., 1RM, %BF, and timed up and go) is included elsewhere in the paper.

Table 3.

Summary of strength training intervention studies in 45–80-year-old women (2010–2020).

After completing this review, several important trends in the literature were noted.

3.2.1. Participant Characteristics

The 38 studies included in this review enrolled a total sample of 2519 participants (mean sample size = 66 participants) with a mean age of 66.89 ± 4.91 years and an age range of 45–80 years.

The majority of participants in these studies were from Brazil (24 studies or 63% included participants from Brazil). Four studies included participants from Spain, three studies included participants from the United States, and a single study was included from each of the following countries: Japan, Sweden, Ireland, Taiwan, Italy and Australia. One study did not identify the ethnic origin of its participants, and one study broadly identified participants as Hispanic.

3.2.2. Summary of Intervention Characteristics

Interventions ranged from 8 to 32 weeks, with an average intervention length of 15 weeks. The majority of interventions were of medium length (>12 weeks but <25 weeks) (n = 34), three interventions were categorized as short length (<12 weeks) [33,34,43], and one intervention was categorized as long length (>25 weeks) [51]. Intervention length was calculated as the number of weeks actively engaged in RT. Periods of time spent detraining, learning technique, or testing were not included in this calculation of intervention length. Interventions, on average, had 2–3 training sessions per week (2.5 + 0.51). Session length (minutes) ranged from 15 to 60 min (mean = 48.89 + 14.53 min). The number of sets per session ranged from 1 to 4 (2.45 ± 0.82). Repetitions per set ranged from 1 to 20 (10.76 ± 1.95). The number of exercises performed ranged from 1 to 12 (7.45 ± 1.97).

There is a need to quantify the volume of exercise without including weight (kg) lifted because the weights used in exercises were individually prescribed, based on 1RMs or band colors for a variety of exercises, and often not included in the papers we analyzed for this review. Importantly, if we do not have an estimate for volume of exercise, it is difficult to link intervention outcomes to program design. Therefore, we propose an estimate of participant exposure to exercise in an attempt to quantify the exercise completed in the studies. Participant exposure is the average number of repetitions (which consisted of the midpoint of the target range of reps) × average number of sets (a midrange was used if groups completed different numbers of sets) × number of exercises included in the intervention. Participant exposure values ranged from 64 to 300, with an average of 210.20 ± 75.87. We were not able to calculate participant exposure for five of the studies due to incomplete information; for some studies, due to training variability in the experimental groups, we calculated averages and used those values.

Two other metrics that can be used to quantify participant exposure to exercise are total number of sessions and total minutes of exercise. Total number of intervention sessions ranged from 16 to 96 with an average of 39.20 ± 16.20, and no data were missing. Total minutes of intervention exercise ranged from 462 to 4320 with an average of 1797.20 ± 921.42, and data on minutes per exercise bout were missing for 21 of the studies.

The majority of interventions (n = 17/38 or 45%) increased intensity of workouts using ACSM recommendations for increasing resistance by a specific percentage for upper and lower body once the maximum number of repetitions were completed in consecutive sessions [59]. A smaller number of studies increased intensity using benchmarks on the Omni (n = 5) or Borg (n = 5) rating of perceived exertion (RPE) (10/38 or 26%), increasing the number of kg lifted once the maximum number of repetitions was completed in consecutive sessions (n = 3/38 or 8%), or target heart rate (n = 1/38 or 3%). Two studies standardized their intensity and increased everyone the same amount at the same time, and 5 studies did not specify how they increased intensity.

Many combinations of repetitions and/or sets were examined in the interventions. Specifically, narrow versus wide range repetition zones (12/10/8 vs. 15/10/5) were examined [33,34], low and high volumes of training were compared [22,27,29,51,52], and 2 vs. 3 times per week of training were compared [24,26,45,50].

In addition to manipulating number of sets and repetitions, several different modalities were compared to RT, including pilates [25], power training emphasizing high-speed concentric movements [27,57], blood flow restriction [39], and photobiomodulation [58].

Dietary supplements or dietary modifications are growing in popularity and have been combined with RT interventions with older women. Eight (8) studies examined the impact of protein combined with resistance training on body composition, strength or functional fitness. Nabuco et al. examined the impact of RT plus existing dietary protein levels [43], whereas others fortified dietary intake with protein [30,35,41,42,44,56] or amino acid supplements [38]. Two studies examined the impact of creatine plus resistance training on body composition, strength, or functional fitness [21,37]. Two studies focused on the impact of a healthy diet on body composition, strength and functional fitness [54,55].

One final factor considered when examining intervention characteristics was study adherence, that is, the percentage of exercises sessions attended. When examining study adherence, nearly half of the studies (16/38 or 42%) did not report study adherence.

3.2.3. Study Quality

In general, study quality, as rated using PEDro, could be improved. One study was rated a 2, three studies were rated 3, 18 studies were rated 4, and 9 studies were rated 5. In total, 82% (31/38) of the studies in this review were rated below medium quality. Seven of the 38 (18%) studies were rated medium to high quality. Most studies were rated lower in quality because they did not conceal allocation, and participants, trainers and assessors were not blinded to group assignment, or this was not reported in the paper.

3.2.4. Effects on Body Composition

Table 4 presents a summary of studies showing the relationship between participant exposure, study duration, adherence, and body composition in older women. Some studies did not report all variables included in the table, so the results will focus on the reported variables. Of the studies that reported on muscle mass changes, 100% (2/2) of the shorter-length studies, 95% (20/21) of the medium-length studies, and 100% (1/1) of the longer-length studies reported increased muscle mass, LBM or FFM. Only one medium-length study did not report changes in muscle mass/LBM or FFM after the intervention [27]. Studies did not report changes in percent body fat as frequently as changes in muscle mass. Of the studies that did report percent body fat, decreases were reported in 100% (1/1) of the shorter studies and 3/8 (38%) of the medium-length studies. Other positive changes in body composition reported included better muscle quality and thickness, increased type II muscle fibers, and a decreased sarcopenic obesity index.

3.2.5. Effects on Muscle Strength

Table 5 presents a summary of studies showing the relationships between participant exposure, study duration, adherence, and muscle strength in older women. Of the studies that measured intervention-related changes in strength, all but one [30] reported at least one increase in upper, lower, or total body strength. Other positive changes reported included enhanced muscle activation, increased isometric hand grip strength, and increased isokinetic torque of the knee.

3.2.6. Effects on Functional Fitness

Table 6 presents a summary of studies showing the relationships between participant exposure, study duration, adherence, and functional fitness in older women. Functional fitness was primarily measured using the timed up-and-go test (TUG), number of chair sit-stands in 30 s, and walking or gait speed. Of the studies that measured functional fitness, 100% improved their TUG (6/6), 30 s chair stands (6/6) and walking or gait speed (9/9). Other functional fitness measures included floor get up time, static balance, countermovement vertical jump (muscular power), timed stair ascent and a 6 min walk test.

Table 4.

Summary of impact of participant exposure, study duration, and adherence in studies that measured body composition in older women.

Table 4.

Summary of impact of participant exposure, study duration, and adherence in studies that measured body composition in older women.

| Study and Duration | # Sets | # Reps (Midpoint of Range) | # Exercises | Participant Exposure Score (Reps × Sets × Exercises) | Total Sessions (Times/Wk × Total # Weeks) | Total Minutes (# Sessions × Minutes/Session) | Adherence | >Muscle Mass, FFM or LBM | <%BF | Other Body Comp Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-length study (<12 wks) | ||||||||||

| dos Santos [33] | 3 | 10 | 8 | 240 | 24 | ? | ≥85% | x | ||

| dos Santos [34] | 3 | 10 | 8 | 240 | 24 | ? | ≥85% | x (mostly android) | ||

| Nabuco [43] | 3 | 10 | 8 | 240 | 24 | ? | ? | High PRO | ||

| Medium-length studies (≥12 to <24 wks) | ||||||||||

| Aguiar [21] | 2 | 12.5 | 8 | 200 | 36 | 2160 | ? | x | NC by measurement | |

| Barbalho [22] | 3.75 | 10 | 8 | 240 | 24 | ? | 95% | |||

| Bocalini [23] | 1 | Timed reps | 12 | ? | 36 | 1800 | >90% | x | not measured | |

| Carrasco-Poyatos [25] | 1 | 8 | 8 | 60 | 36 | 2160 | ? | >both Pilates and RT | ||

| Cavalcante [26] | 1 | 12.5 | 8 | 250 | 40 | 1200 | ≥85% | Both 2x/wk and 3x/wk< | ||

| Coelho-Junior [27] | 2 | 13.5 | 9 | 364.5 | 44 | ? | 89% | NC | NC by measure | |

| Cunha [29] | 2 | 12.5 | 8 | 100 LV or 300 HV | 36 | 540 LV or 1620 HV | ≥85% | >both low and high volume | ||

| Daly [30] | 3 | 9 | 7 | 189 | 48 | 2880 | 89% | >in LBM, FFM in fortified milk group | %BF < in both grps but more in Milk Grp | <Fat mass |

| Francis [35] | 3.5 | 12 | 9 | 378 | 36 | 1908 | 82–86% | >leg lean tissue in both PRO + PRO + RT | ||

| Gadelha [36] | 3 | 10 | 8 | 240 | 72 | ? | ≥75% | >FFM in RT vs. CTL | NC | Sarcopenic obesity index > in RT vs. CTL |

| Gualano [37] | 2 | 10 | 7 | 175 | 60 | ? | ≥84% | RT + CR ≥ appendicular LBM vs. PL, CR and PL + RT | Fat mass (kg) did not change between grps | |

| Kim [38] | 1 | 8 | varying | ? | 24 | ? | 70–80% | Leg LBM > EX + AA and EX | ||

| Liao [40] | 3 | 10 | 8 | 240 | 36 | 1980 | ? | Ex bands > LBM | %BF < in EG vs. CG | Ex bands > muscle quality |

| Mori [41] | 2.5 | 10 | 7 | 175 | 48 | ? | 87–90% | >LBM in EX + PRO vs. EX or PRO | ||

| Nabuco [42] | 3 | 10 | 8 | 240 | 36 | ? | ? | Exercise + whey PRO > LBM vs. placebo | ||

| Nabuco [44] | 3 | 8 | 8 | 192 | 36 | ? | ? | RT+ PRO > LBM vs. RT+PLA | <%BF in RT + PRO vs. RT + PLA | |

| Nascimento [45] | 1 | 12.5 | 8 | 100 | 48 (2x) or 72 (3x) | ? | 92–93% adherence | 2 or 3x/wk > LBM | ||

| Rabelo [46] | 3 | 10 | 10 | 300 | 72 | 4320 | ≥85% | RT > LBM | ||

| Radaelli [47] | 2 | 14.5 | 10 | L: 145 H: 435 | 26 | L: 585 H: 1430 | Muscle thickness and neuromuscular adaptations > similarly in both groups | |||

| Ribeiro [51] | 3 | 11.5 | 8 | 300 | 96 | ? | ≥85% | Both pyramid and constant training > LBM | Neither grp changed | |

| Ribeiro [52] | 3 | 10 | 8 | 240 | 48 | ? | ≥85% | Both pyramid and trad > LBM | ||

| Strandberg [54] | 3 | 13.5 | 7 | 283.5 | 48 | ? | ? | Lean leg mass > only in RT + healthy diet | ||

| Strandberg [55] | 3 | 13.5 | 7 | 283.5 | 48 | ? | ? | Sig hypertrophy of T2 muscle fibers only in RT + PUFA-not RT only or CTL | ||

| Sugihara [56] | 3 | 10 | 8 | 240 | 36 | 1800 | ? | Both RT+PRO and RT + PLA > LBM (but RT + PRO >) | Both RT+PRO and RT + PLA > muscle quality | |

AA = amino acids; %BF = percent body fat; CTL or CG = control group; EG = experimental group; FFM = fat-free mass; LBM = lean body mass; NC = no change; PLA = placebo; PRO = protein; PUFA = polyunsaturated fatty acids; RT = resistance training.

Table 5.

Summary of impact of participant exposure, study duration, and adherence in studies that measured muscular strength in older women.

Table 5.

Summary of impact of participant exposure, study duration, and adherence in studies that measured muscular strength in older women.

| Study and Duration | PS | # Sets | # Reps (Midpoint of Range) | # Exercises | Participant Exposure Score (Reps × Sets × Exercises) | Total Sessions (Times/Wk × Total # Weeks) | Total Minutes (# Sessions × Minutes/Session) | Adherence | 1RM Bench or Chest Press | 1RM Bicep Curl (or > Timed Curl) | >1RM Knee Extension | >1RM Leg Press | Other Strength Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-length studies (<12 wks) | |||||||||||||

| dos Santos [33] | 5 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 240 | 24 | ? | ≥85% | x | x | x | x | |

| Nabuco [43] | 2 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 240 | 24 | ? | ? | High PRO | Total strength > high PRO | |||

| Medium-length studies (≥12 to <24 wks) | |||||||||||||

| Aguiar [21] | 7 | 2 | 12.5 | 8 | 200 | 36 | 2160 | ? | x | x | x | ||

| Barbalho [22] | 4 | 3.75 | 10 | 8 | 240 | 24 | ? | 95% | x | x | x | ||

| Correa [28] | 5 | 3 | ? | 3 lower body | ? | 36 | ? | x | >muscle activation | ||||

| Cunha [29] | 4 | 2 | 12.5 | 8 | 100 LV or 300 HV | 36 | 540 LV or 1620 HV | ≥85% | x | x | |||

| Daly [30] | 4 | 3 | 9 | 7 | 189 | 48 | 2880 | 89% | NS diff in muscle strength. Why? Adherence was good | ||||

| de Resende-Netro [31] | 5 | 2 | 9 | 8 | 144 | 36 | 1620 | ? | Functional and trad RT > strength | ||||

| Francis [35] | 4 | 3.5 | 12 | 9 | 378 | 36 | 1908 | 82–86% | >in PRO + RT | ||||

| Gualano [37] | 6 | 2 | 10 | 7 | 175 | 60 | ? | ≥84% | >1RM bench press in RT + CR | >1RM Leg Press in RT + CR | |||

| Kim [38] | 4 | 1 | 8 | varying | ? | 24 | ? | 70–80% | >only in EX + AA | ||||

| Letieri [39] | 6 | 4 | ? | High or low blood flow occlusion | H: 112 or L: 240 | 48 | 2160 | ? | Isokinetic torque of KE (R/L) and LC higher in both groups | ||||

| Nabuco [42] | 5 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 240 | 36 | ? | ? | >WP vs. PLA | >WP vs. PLA | >total strength in WP vs. PLA | ||

| Nabuco [44] | 6 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 192 | 36 | ? | ? | Both> | Both> | Both> | Both > total strength | |

| Rabelo [46] | 4 | 3 | 10 | 10 | 300 | 72 | 4320 | ≥85% | RT > KE peak torque | ||||

| Radaelli [47] | 3 | 2 | 14.5 | 10 | L: 145 H: 435 | 26 | L: 585 H: 1430 | 1RM KE > both grps | Muscle activation > both grps | ||||

| Ramirez-Campillo [49] | 4 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 192 | 36 | ? | ? | High and low spd > strength | ||||

| Ramirez-Campillo [50] | 4 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 2x = 192 3x = 128 | 2x = 24 3x = 36 | 2x = 1440 3x = 2160 | ? | > isometric hand grip strength | ||||

| Ribeiro [51] | 4 | 3 | 11.5 | 8 | 300 | 96 | ? | ≥85% | Both pyramid and constant training > | ||||

| Ribeiro [52] | 5 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 240 | 48 | ? | ≥85% | Both pyramid and trad > | Both pyramid and trad > | Both pyramid and trad > | ||

| Strandberg [54] | 4 | 3 | 13.5 | 7 | 283.5 | 48 | ? | ? | RT+HD and RT > vs. CTL | ||||

| Sugihara [56] | 5 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 240 | 36 | 1800 | ? | Both > WP > PLA | Both > WP > PLA | Both > WP > PLA | ||

| Tiggeman [57] | 4 | 2 | 12 | 6 | 144 | 24 | ? | ? | Both > KE | Both > LP | |||

1RM = 1-repetition maximum; AA = amino acid; CON or CTL = control group; CR = Creatine; FFM = fat-free mass; HV = high volume; KE = knee extension; LBM = lean body mass; LC = leg curl; LV = low volume; NS = non-significant changes; PLA = placebo; PRO = protein; PS = PEDRO Score; RT = resistance training; WP = whey protein.

Table 6.

Summary of impact of participant exposure, study duration, and adherence on functional fitness (FF) in older women.

Table 6.

Summary of impact of participant exposure, study duration, and adherence on functional fitness (FF) in older women.

| Study and Duration | PS | # Sets | # Reps (Midpoint of Range) | # Exercises | Participant Exposure Score (Reps × Sets × Exercises) | Total Sessions (Times/Wk × Total # Weeks) | Total Minutes (# Sessions × Minutes/Session) | Adherence | <TUG Time | >30 s Chair Stands | >Walking or Gait Speed | Other FF Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium-length studies (≥12 to <24 wks) | ||||||||||||

| Aguiar [21] | 7 | 2 | 12.5 | 8 | 200 | 36 | 2160 | ? | x | <floor get up time | ||

| Barbalho [22] | 4 | 3.75 | 10 | 8 | 240 | 24 | ? | 95% | x | |||

| Carrasco-Poyatos [25] | 3 | 1 | 8 | 8 | 60 | 36 | 2160 | ? | Pilates > RT and CTL | RT > static balance | ||

| Coelho-Junior [27] | 6 | 2 | 13.5 | 9 | 364.5 | 44 | ? | 89% | x | >CM jump; balance | ||

| Correa [28] | 5 | 3 | ? | 3 lower body | ? | 36 | ? | >in rapid strength only | <CM jump in rapid strength only | |||

| Daly [30] | 4 | 3 | 9 | 7 | 189 | 48 | 2880 | 89% | Both grps > stair ascent | |||

| de Resende-Netro [31] | 5 | 2 | 9 | 8 | 144 | 36 | 1620 | ? | >Only in functional training | |||

| Francis [35] | 4 | 3.5 | 12 | 9 | 378 | 36 | 1908 | 82–86% | >Gait speed in PRO + RT | |||

| Kim [38] | 4 | 1 | 8 | varying | ? | 24 | ? | 70–80% | >in all int grps | |||

| Liao [40] | 4 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 240 | 36 | 1980 | ? | <TUG score | >chair rise | >gait speed | |

| Mori [41] | 4 | 2.5 | 10 | 7 | 175 | 48 | ? | 87–90% | >gait speed in EX + PRO vs. PRO alone | |||

| Nabuco [42] | 5 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 240 | 36 | ? | ? | <10 m walk test time | |||

| Radaelli [47] | 3 | 2 | 14.5 | 10 | L: 145 H: 435 | 26 | L: 585 H: 1430 | |||||

| Radaelli [48] | 5 | 2 | 10 | 7 | L: 70 H: 210 | 24 | L: 720 H: 1200 | ≥85% | Both grps > VJ | |||

| Ramirez-Campillo [49] | 4 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 192 | 36 | ? | ? | High spd < TUG vs. lo spd | High spd > gait speed and ball throw vs. low spd | ||

| Ramirez-Campillo [50] | 4 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 2x = 192 3x = 128 | 2x = 24 3x = 36 | 2x = 1440 3x = 2160 | ? | Both < TUG score | Both > chair rise score | Both > 10 m walk | |

| Souza [53] | 4 | 2 | 12 | varied | 72 | 28 | 462 | >80% | Trad RT > walk speed vs. elastic band | |||

| Tiggeman [57] | 4 | 2 | 12 | 6 | 144 | 24 | ? | ? | <TUG score | >chair rise score | >distance on 6 min walk test; >stair climb | |

CM = countermovement; CON or CTL = control group; FF = functional fitness; H = high volume; L = low volume; NS = non-significant changes; PRO = protein; PS = PEDRO Score; RT = resistance training; TUG = timed up and go.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to review the literature on the impact of RT on body composition (BC), muscle strength (MS) and functional fitness (FF) in older women, typically of peri- to postmenopausal age. We summarized the typical study length (weeks), participant exposure (set/repetitions/number of exercises), total sessions and total minutes. The most important findings were: (a) most studies that tested for increased muscle mass, lean body mass or fat-free mass found increases with RT; fewer studies examined changes in percent body fat, but those that did found no effect of RT on %BF with RT, regardless of length of study, participant exposure or other important variables; (b) all studies that measured strength found that at least one muscle group got stronger with an RT intervention; and (c) all studies that measured functional fitness improved at least one aspect with RT. The pattern of empirical results points to the benefits of RT on muscle strength, and functional fitness examined in our review. The benefits of RT on FFM were also significant, although the findings relative to percent body fat need additional study. Even with these findings, there is still a need for additional studies examining the dose–response effects of RT on older, peri- to postmenopausal women.

Our review reveals a greater degree of consistency in the impact of RT on older women than has been established in prior reviews. We noted that the majority of studies for this review included women from Brazil. This is likely because Brazil made a significant investment in public health research in the mid 2000s [60]. Published research does not enable examination of differential effects among sub-groups of women in peri- to postmenopausal groups. This gap in our knowledge needs to be rectified if we are to provide equitable health care to women and in particular, peri- to postmenopausal women, across social contexts.

All of the studies reviewed included interventions that were more than 8 weeks in duration. In addition, most utilized multiple sets, exercises and repetitions, which were quantified as participant exposure. This could be one reason why the studies reviewed in this paper overwhelmingly found positive increases in muscle mass, muscle strength and functional fitness. It is well documented that exercise dose is related to the amount of positive change [61]. Previous reviews have not attempted to quantify participant exposure due to the lack of published information about the amount of weight lifted. We believe that in the absence of information about weight lifted, as is common in studies that use resistance from body weight, TRX, or elastic bands, it is important to quantify RT exercise as participant exposure.

Resistance training has been shown to consistently increase muscular strength in women, but the impact on muscle mass is still being debated because an increase in muscle strength does not always correspond to an increase in muscle mass, particularly in older women. Interestingly, percent body fat did not consistently change as a result of RT in many of the studies, but this may have been because of possible variability in measures used to detect percent body fat (e.g., skinfold calipers vs. DXA).

The most frequently utilized measures for functional fitness in this review were the timed up-and-go test, the 30 s chair stand, and walking and gait speed. Other measures used less frequently included floor get up time, static balance, countermovement/vertical jump, and stair ascent. Overwhelmingly, these studies demonstrated improvements in functional fitness.

We recommend continuing to standardize reporting requirements for publishing RT interventions and requiring data about sets, repetitions, weights lifted, minutes per session and adherence. Improving detailed information will enable us to better link work performed with outcomes. Inconsistent findings from previous studies are likely due to differences in training interventions (e.g., number of sets, repetitions, and overall weeks of training), heterogeneous samples studied, small sample sizes (combined with lack of statistical power), inadequate doses of resistance training and/or a lack compliance to the training—which was not reported in many cases. We also believe that it is not advisable to include a control group in these studies because comparisons should be made between various types of RT protocols since we concluded that RT has positive effects on body composition, muscular strength and functional fitness.

Overwhelmingly, the studies reviewed in this paper supported the positive benefits of combining protein supplementation with RT for strength gains in women 45 yearss of age and older. Creatine supplementation had some positive benefits as well. Our review is in agreement with two pre-2010 randomized controlled trials conducted with older women consuming a creatine supplement of 0.3 g kg body mass−1 three times daily over a 7 day period without exercise training; these studies showed improvement in lower extremity functional capacity [62,63] and increases in upper- and lower-body dynamic strength and mean explosive power [63]. In addition to strength, power, and functional gains without resistance training, creatine may also protect against mitochondrial damage from oxidation that occurs as a result of aging [64].

Additional studies have examined the impact of nutritional manipulation or supplements on RT in older women. For example, researchers examined whether long-chain n-3 PUFA (polyunsaturated fatty acids) enhanced adaptations to an 18 week twice-weekly lower-limb resistance training intervention in older women; they found that compared to men who supplemented with long-chain n-3 PUFA, women who supplemented improved muscle function and quality [65]. Other researchers have examined the impact of leucine ingestion (2x daily at 4.2 g/serving) on acute muscle response to RT [66]. More research should be done to examine the effects of nutritional supplements combined with RT in older women to establish consistent and appropriate recommendations.

4.1. Limitations

Although our findings added to the literature related to the health benefits of RT in older women, this group of studies is not without limitations. Limitations identified should be used to plan future research directions and continue to improve the quality of studies with older women. First, most of the women in this review were from Brazil. Although we do not expect ethnic differences in responses to RT, it is important to acknowledge that results may not be generalizable to broader international populations. Second, we did not examine changes in body composition, muscle strength, and functional fitness by age. This was difficult due to the fact that many studies included women within a certain age range and reported mean age without reporting changes or differences by age groupings. Although previous researchers have shown that positive changes slow with age [67], that was not the purpose of this study, and it would not have been possible to conduct an analysis by age groupings due to the way data were reported in the studies included. Third, when measuring body composition, many studies used bioelectric impedance or skinfold calipers instead of DXA, the gold standard. Depending on the skill of the researcher when using skinfold calipers, and the hydration status of the participants who measure body composition with BIA, results may vary significantly. Fourth, muscle strength was mostly obtained using 1RM (dynamic strength) for both upper- and lower-body exercises. Obtaining 1RM was sometimes based on an estimate (e.g., 3RM) and sometimes based on a true 1RM. The quality of 1RM results may depend on the willingness of participants to push themselves and/or on the skill of the person administering the 1RM tests. Fifth, in addition to dynamic strength, isometric strength (e.g., isometric hand grip) was tested. Activities of daily living likely contain both dynamic and isometric strength requirements, so including both in a testing protocol would improve study quality. A sixth concern is that the most frequently utilized functional fitness tests included the TUG, 30 s chair stands, and walking speed. Scores on these tests typically can provide an index of fall risk in older adults [68], so specifically tying RT training protocol and muscles utilized to functional fitness tests performed would also improve study quality. A sixth concern is that although these studies were done with women in peri- to postmenopausal age groups, few studies reported HRT status. Of those that did include HRT status, information about type of HRT or dosage was rarely included. Adding HRT status to these studies would enable examination of the potential impact of hormones on response to resistance training. Seventh, our review included only studies between 2010 and 2020. Studies published before or after this date may contain additional information. In addition, we proposed a unique way to quantify exercise during the programs (i.e., participant exposure) so we could compare interventions in light of the absence of specific weight (kg) being included for many of the exercises. Clearly, additional metrics are needed to quantify exercise in this population. Our proposed measure is exploratory, and in need of additional verification.

Another concern is that so few studies were categorized as medium to high quality using the PEDro scale. This is likely because it is difficult, in training studies, to include control groups when we know that RT protocols typically have beneficial outcomes in terms of body composition, muscular strength, and functional fitness. In addition, whereas participants and trainers may have been blinded to study conditions, this was not explicitly stated in published papers. A large number of studies did not report adherence to training sessions, thus, the studies did not receive quality points for ensuring that key outcomes were obtained by more than 85% of the participants. Furthermore, allocation concealment, which hides the assignment of participants into treatment groups, was rarely reported in studies. Ultimately, while some studies received low scores on measures of allocation concealment or blinding participants and trainers to group assignment, other measures such as specifying eligibility criteria, random assignment, similar groups at baseline, and reporting between group results for at least one outcome, were regularly reported, and indicative of high quality-research. Again, specifying what constitutes high quality RT research, and standardization of these measures is important. An eighth concern is that although we proposed a strategy to quantify participant exposure, without more information on study adherence, reasons for dropout, etc., it will be difficult to replicate these results, or more importantly, to make specific clinical or exercise recommendations for older women. A related concern is that unmeasured changes in general physical activity over the training period is a plausible threat to internal validity in the studies reviewed. Incremental gains from training may be associated with commensurate increases in general physical activity, which may contribute to gains in mass and strength. Physical activity beyond the study design should be monitored and factored into analyses of future studies. Finally, regardless of which test was utilized, information about tester training and inter-tester reliability was only sporadically provided.

4.2. Future Research Directions

This review identified several areas that should be included in future research studies in order to continue to advance the science related to optimizing RT in older women. Studies comparing individualized and group training would enable the detection of benefits of social engagement, as part of the training regimen. In addition, it would be interesting to conduct a study comparing study results by ethnic group to determine whether differences exist. To our knowledge, no one has examined cost-effectiveness or cost–benefit of RT in this population in terms of health care costs or compared to other modalities of exercise [69]. Further, most studies were completed 2–3 d/wk and most were of medium length. Expanding the length of studies (wks) and/or the number of days/wk for studies would enable further examination of the dose–response of RT in this population, as would including effect sizes and conducting a meta-analysis. Although some studies have examined the impact of nutritional supplements on RT results, there is a need to continue to examine adding protein or creatine or other dietary modifications or nutritional supplements to RT in older women. There is also a need to continue to compare RT modalities beyond free weights, machines, dumbbells, and resistance bands. Comparing traditional RT modalities to interventions that are low cost and home based (e.g., TRX and body weight exercises) is worth examining [12]. Most of the studies summarized overall results and did not break down samples by age group, for example, in 5 to 10-year increments. This made it difficult to ascertain age-related changes and differences. In addition, many authors did not include HRT status, and if they did, information about HRT dosage was rarely included. Future research addressing smaller age ranges and including specific information about HRT would improve the ability to tease out age and hormone-related effects. Finally, although one study each was completed using blood flow restriction and photomobulation, more research is needed to determine modality effectiveness in this population.

5. Conclusions

This review concluded that most RT studies with older, peri- to postmenopausal women showed net positive results. RT, with or without nutritional supplementation, has promise and can improve muscle mass, strength, and key measures of functional fitness. In addition, we highlighted gaps in the research on the efficacy of RT to improve the strength of this group of women. Given the relationship between these outcome measures and key factors supporting independence and quality of life (e.g., ability to engage in activities of daily living and decrease the incidence of falls), it is clear that greater insight about the impact of varied modalities and doses of RT on older women would improve outcomes. More rigorous studies are needed to provide clear recommendations for RT for older women to slow the onset or reduce the severity of sarcopenia and subsequent decline in physical ability and increase in frailty. Research with subjects stratified by baseline levels of muscle mass, strength and functional fitness would yield information to inform prescriptions for training as women experience age-related loss of fitness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.B.R., H.A.W., N.L., C.L., A.L.S., K.P., P.S.P., D.B. and R.C.; Methodology, L.B.R., H.A.W., N.L., C.L. and A.L.S.; Validation, L.B.R., H.A.W., N.L., C.L., A.L.S., K.P., P.S.P. and D.B.; Formal Analysis, L.B.R., H.A.W., N.L., C.L., A.L.S., K.P., P.S.P., D.B. and R.C.; Data Curation, L.B.R., H.A.W., N.L., C.L., A.L.S., K.P., P.S.P., D.B. and R.C.; Writing-original draft preparation, L.B.R., N.L. and C.L.; Writing-review and editing, L.B.R., H.A.W., N.L., C.L., A.L.S., K.P., P.S.P., D.B. and R.C.; Project Administration, L.B.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by an NIMHD center grant to the Southwest Health Equity Research Collaborative at Northern Arizona University (U54MD012388).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it was a literature review and no new data were collected.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not necessary because previous researchers collected the data synthesized in this literature review.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Volpi, E.; Nazemi, R.; Fujita, S. Muscle tissue changes with aging. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2004, 7, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, J.R.; Officer, A.; de Carvalho, I.A.; Sadana, R.; Pot, A.M.; Michel, J.P.; Lloyd-Sherlock, P.; Epping-Jordan, J.E.; Peeters, G.M.E.E.; Mahanani, W.R.; et al. The world report on ageing and health: A policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utian, W.H. Biosynthesis and physiologic effects of estrogen and pathophysiologic effects of estrogen deficiency: A review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1989, 161, 1828–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; Jee, W.S.S.; Chen, J.L.; Mo, A.; Setterberg, R.B.; Su, M.; Tian, X.Y.; Ling, Y.F.; Yao, W. Estrogen and “Exercise” Have a Synergistic Effect in Preventing Bone Loss in the Lumbar Vertebra and Femoral Neck of the Ovariectomized Rat. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2003, 72, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamman, M.M.; Hill, V.J.; Adams, G.R.; Haddad, F.; Wetzstein, C.G.; Gower, G.A.; Ahmed, A.; Hunter, G.R. Gender differences in resistance training induced myofiber hypertrophy among older adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2003, 58, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, S.K.; Rook, K.M.; Siddle, N.C.; Bruce, S.A.; Woledge, R.C. Muscle weakness in women occurs at an earlier age than in men, but strength is preserved by hormone replacement therapy. Clin. Sci. 1993, 84, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, T.V.; Dalgaard, L.B.; Ringgaard, S.; Johansen, F.T.; Bengtsen, M.B.; Mose, M.; Lauritsen, K.M.; Ortenblad, N.; Gravholt, C.H.; Hansen, M. Transdermal estrogen therapy improves gains in skeletal muscle mass after 12 weeks of resistance training in early postmenopausal women. Front. Physiol. 2021, 11, 596130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, M.A.; Moylan, J.S.; Reid, M.B. Physical inactivity and muscle weakness in the critically ill. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 37, S337–S346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerome, G.J.; Glass, T.A.; Mielke, M.; Xue, Q.-L.; Andersen, R.E.; Fried, L.P. Physical activity participation by presence and type of functional deficits in older women: The Women’s Health and Aging Studies. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2006, 61, 1171–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, L.; Semmlinger, L.; Rohleder, N. Resistance training as an acute stressor in healthy young men: Associations with heart rate variability, alpha-amylase, and cortisol levels. Stress 2020, 24, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, P.J.; Cuperio, R.; Ramos-Campo, D.J.; Alcaraz, P.E.; Rubio-Arias, J.Á. Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Resistance Training on Whole-Body Muscle Growth in Healthy Adult Males. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín-Cascales, E.; Alcaraz, P.E.; Ramos-Campo, D.J.; Rubio-Arias, J.A. Effects of multicomponent training on lean and bone mass in postmenopausal and older women: A systematic review. Menopause 2018, 25, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín-Cascales, E.; Alcaraz, P.E.; Ramos-Campo, D.J.; Martinez-Rodriguez, A.; Chung, L.H.; Rubio-Arias, J.Á. Whole-body vibration training and bone health in postmenopausla women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2018, 97, e11918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabbour, G.; Iancu, H.D. Comparison of performance and health indicators between perimenopausal and postmenopausal obese women: The effect of high-intensity interval training (HIIT). Menopause 2020, 28, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devries, M.C.; Phillips, S.M. Creatine supplementation during resistance training in older adults—A meta-analysis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2014, 46, 1194–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, D.K.; Quinn, M.A.; Saunders, D.H.; Greig, C.A. Protein Supplementation Does Not Significantly Augment the Effects of Resistance Exercise Training in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 959-e1–959-e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.-D.; Tsauo, J.-Y.; Wu, Y.-T.; Cheng, C.-P.; Chen, H.-C.; Huang, Y.-C.; Chen, H.-C.; Liou, T.-H. Effects of protein supplementation combined with resistance exercise on body composition and physical function in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 1078–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015, 354, i4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PEDro Scale. Available online: https://pedro.org.au/wp-content/uploads/PEDro_scale.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Evidence Based Medicine-PICO. Available online: https://researchguides.uic.edu/c.php?g=252338&p=3954402 (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Aguiar, A.F.; Januário, R.S.; Junior, R.P.; Gerage, A.M.; Pina, F.L.; do Nascimento, M.A.; Padovani, C.R.; Cyrino, E.S. Long-term creatine supplementation improves muscular performance during resistance training in older women. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013, 113, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, M.S.M.; Gentil, P.; Izquierdo, M.; Fisher, J.; Steele, J.; Raiol, R.A. There are no no-responders to low or high resistance training volumes among older women. Exp. Gerontol. 2017, 99, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocalini, D.S.; Lima, L.S.; de Andrade, S.; Madureira, A.; Rica, R.L.; Santos, R.N.D.; Serra, A.J.; Silva, J.A., Jr.; Rodriguez, D.; Figueira, A., Jr.; et al. Effects of circuit-based exercise programs on the body composition of elderly obese women. Clin. Interv. Aging 2012, 7, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, N.H.; Ribeiro, A.S.; Nascimento, M.A.; Gobbo, L.A.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Júnior, A.A.; Gobbi, S.; Oliveira, A.R.; Cyrino, E.S. Effects of different resistance training frequencies on flexibility in older women. Clin. Interv. Aging 2015, 10, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Poyatos, M.; Rubio-Arias, J.A.; Ballesta-García, I.; Ramos-Campo, D.J. Pilates vs. muscular training in older women. Effects in functional factors and the cognitive interaction: A randomized controlled trial. Physiol. Behav. 2019, 201, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, E.F.; Ribeiro, A.S.; do Nascimento, M.A.; Silva, A.M.; Tomeleri, C.M.; Nabuco, H.C.G.; Pina, F.L.C.; Mayhew, J.L.; Da Silva-Grigoletto, M.E.; da Silva, D.R.P.; et al. Effects of Different Resistance Training Frequencies on Fat in Overweight/Obese Older Women. Int. J. Sports Med. 2018, 39, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho-Júnior, H.J.; de Oliveira Gonçalvez, I.; Sampaio, R.A.C.; Sampaio, P.Y.S.; Cadore, E.L.; Izquierdo, M.; Marzetti, E.; Uchida, M.C. Periodized and non-periodized resistance training programs on body composition and physical function of older women. Exp. Gerontol. 2019, 121, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, C.S.; LaRoche, D.P.; Cadore, E.L.; Reischak-Oliveira, A.; Bottaro, M.; Kruel, L.F.; Tartaruga, M.P.; Radaelli, R.; Wilhelm, E.N.; Lacerda, F.C.; et al. 3 Different types of strength training in older women. Int. J. Sports Med. 2012, 33, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, P.M.; Nunes, J.P.; Tomeleri, C.M.; Nascimento, M.A.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Antunes, M.; Gobbo, L.A.; Teixeira, D.; Cyrino, E.S. Resistance Training Performed with Single and Multiple Sets Induces Similar Improvements in Muscular Strength, Muscle Mass, Muscle Quality, and IGF-1 in Older Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 1008–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, R.M.; Gianoudis, J.; De Ross, B.; O’Connell, S.L.; Kruger, M.; Schollum, L.; Gunn, C. Effects of a multinutrient-fortified milk drink combined with exercise on functional performance, muscle strength, body composition, inflammation, and oxidative stress in middle-aged women: A 4-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 427–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Resende-Neto, A.G.; do Nascimento, M.A.; de Sá, C.A.; Ribeiro, A.S.; Desantana, J.M.; da Silva-Grigoletto, M.E. Comparison between functional and traditional training exercises on joint mobility, determinants of walking and muscle strength in older women. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2019, 59, 1659–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Resende-Neto, A.G.; Andrade, B.C.O.; Cyrino, E.S.; Behm, D.G.; De-Santana, J.M.; Da Silva-Grigoletto, M.E. Effects of functional and traditional training in body composition and muscle strength components in older women: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 84, 103902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, L.D.; Ribeiro, A.S.; Cavalcante, E.F.; Nabuco, H.C.; Antunes, M.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Cyrino, E.S. Effects of Modified Pyramid System on Muscular Strength and Hypertrophy in Older Women. Int. J. Sports Med. 2018, 39, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, L.D.; Ribeiro, A.S.; Nunes, J.P.; Tomeleri, C.M.; Nabuco, H.C.G.; Nascimento, M.A.; Junior, P.S.; Fernandes, R.R.; Campa, F.; Toselli, S.; et al. Effects of Pyramid Resistance-Training System with Different Repetition Zones on Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Older Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, P.; Mc Cormack, W.; Toomey, C.; Norton, C.; Saunders, J.; Kerin, E.; Lyons, M.; Jakeman, P. Twelve weeks’ progressive resistance training combined with protein supplementation beyond habitual intakes increases upper leg lean tissue mass, muscle strength and extended gait speed in healthy older women. Biogerontology 2017, 18, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadelha, A.B.; Paiva, F.M.; Gauche, R.; de Oliveira, R.J.; Lima, R.M. Effects of resistance training on sarcopenic obesity index in older women: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, 65, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualano, B.; Macedo, A.R.; Alves, C.R.; Roschel, H.; Benatti, F.B.; Takayama, L.; de Sá Pinto, A.L.; Lima, F.R.; Pereira, R.M. Creatine supplementation and resistance training in vulnerable older women: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Exp. Gerontol. 2014, 53, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.K.; Suzuki, T.; Saito, K.; Yoshida, H.; Kobayashi, H.; Kato, H.; Katayama, M. Effects of Exercise and Amino Acid Supplementation on Body Composition and Physical Function in Community-Dwelling Elderly Japanese Sarcopenic Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letieri, R.V.; Teixeira, A.M.; Furtado, G.E.; Lamboglia, C.G.; Rees, J.L.; Gomes, B.B. Effect of 16 weeks of resistance exercise and detraining comparing two methods of blood flow restriction in muscle strength of healthy older women: A randomized controlled trial. Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 114, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.D.; Tsauo, J.Y.; Huang, S.W.; Ku, J.W.; Hsiao, D.J.; Liou, T.H. Effects of elastic band exercise on lean mass and physical capacity in older women with sarcopenic obesity: A randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, H.; Tokuda, Y. Effect of whey protein supplementation after resistance exercise on the muscle mass and physical function of healthy older women: A randomized controlled trial. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2018, 18, 1398–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabuco, H.C.G.; Tomeleri, C.M.; Junior, P.S.; Fernandes, R.R.; Cavalcante, E.F.; Antunes, M.; Ribeiro, A.S.; Teixeira, D.C.; Silva, A.M.; Sardinha, L.B.; et al. Effects of Whey Protein Supplementation Pre- or Post-Resistance Training on Muscle Mass, Muscular Strength, and Functional Capacity in Pre-Conditioned Older Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2018, 10, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabuco, H.C.; Tomeleri, C.M.; Junior, P.S.; Fernandes, R.R.; Cavalcante, E.F.; Nunes, J.P.; Cunha, P.F.; Dos Santos, L.; Cyrino, E.S. Effects of higher habitual protein intake on resistance-training-induced changes in body composition and muscular strength in untrained older women: A clinical trial study. Nutr. Health 2019, 25, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabuco, H.C.G.; Tomeleri, C.M.; Fernandes, R.R.; Junior, P.S.; Cavalcante, E.F.; Cunha, P.M.; Antunes, M.; Nunes, J.P.; Venturini, D.; Barbosa, D.S.; et al. Effect of whey protein supplementation combined with resistance training on body composition, muscular strength, functional capacity, and plasma-metabolism biomarkers in older women with sarcopenic obesity: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2019, 32, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, M.A.D.; Gerage, A.M.; Silva, D.; Ribeiro, A.S.; Machado, D.; Pina, F.L.C.; Tomeleri, C.M.; Venturini, D.; Barbosa, D.S.; Mayhew, J.L.; et al. Effect of resistance training with different frequencies and subsequent detraining on muscle mass and appendicular lean soft tissue, IGF-1, and testosterone in older women. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2019, 19, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabelo, H.T.; Bezerra, L.A.; Terra, D.F.; Lima, R.M.; Silva, M.A.; Leite, T.K.; de Oliveira, R.J. Effects of 24 weeks of progressive resistance training on knee extensors peak torque and fat-free mass in older women. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 2298–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radaelli, R.; Botton, C.E.; Wilhelm, E.N.; Bottaro, M.; Lacerda, F.; Gaya, A.; Moraes, K.; Peruzzolo, A.; Brown, L.E.; Pinto, R.S. Low- and high-volume strength training induces similar neuromuscular improvements in muscle quality in elderly women. Exp. Gerontol. 2013, 48, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radaelli, R.; Brusco, C.M.; Lopez, P.; Rech, A.; Machado, C.L.F.; Grazioli, R.; Müller, D.C.; Tufano, J.J.; Cadore, E.L.; Pinto, R.S. Muscle quality and functionality in older women improve similarly with muscle power training using one or three sets. Exp. Gerontol. 2019, 128, 110745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Campillo, R.; Castillo, A.; de la Fuente, C.I.; Campos-Jara, C.; Andrade, D.C.; Álvarez, C.; Martínez, C.; Castro-Sepúlveda, M.; Pereira, A.; Marques, M.C.; et al. High-speed resistance training is more effective than low-speed resistance training to increase functional capacity and muscle performance in older women. Exp. Gerontol. 2014, 58, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Diaz, D.; Martinez-Salazar, C.; Valdés-Badilla, P.; Delgado-Floody, P.; Méndez-Rebolledo, G.; Cañas-Jamet, R.; Cristi-Montero, C.; García-Hermoso, A.; Celis-Morales, C.; et al. Effects of different doses of high-speed resistance training on physical performance and quality of life in older women: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 11, 1797–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.S.; Aguiar, A.F.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Nunes, J.P.; Cavalcante, E.F.; Cadore, E.L.; Cyrino, E.S. Effects of Different Resistance Training Systems on Muscular Strength and Hypertrophy in Resistance-Trained Older Women. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.S.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Fleck, S.J.; Pina, F.L.C.; Nascimento, M.A.; Cyrino, E.S. Effects of Traditional and Pyramidal Resistance Training Systems on Muscular Strength, Muscle Mass, and Hormonal Responses in Older Women: A Randomized Crossover Trial. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 1888–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, D.; Barbalho, M.; Vieira, C.A.; Martins, W.R.; Cadore, E.L.; Gentil, P. Minimal dose resistance training with elastic tubes promotes functional and cardiovascular benefits to older women. Exp. Gerontol. 2019, 115, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strandberg, E.; Edholm, P.; Ponsot, E.; Wåhlin-Larsson, B.; Hellmén, E.; Nilsson, A.; Engfeldt, P.; Cederholm, T.; Risérus, U.; Kadi, F. Influence of combined resistance training and healthy diet on muscle mass in healthy elderly women: A randomized controlled trial. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 119, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strandberg, E.; Ponsot, E.; Piehl-Aulin, K.; Falk, G.; Kadi, F. Resistance Training Alone or Combined With N-3 PUFA-Rich Diet in Older Women: Effects on Muscle Fiber Hypertrophy. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2019, 74, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, P.S.; Ribeiro, A.S.; Nabuco, H.C.G.; Fernandes, R.R.; Tomeleri, C.M.; Cunha, P.M.; Venturini, D.; Barbosa, D.S.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Cyrino, E.S. Effects of Whey Protein Supplementation Associated With Resistance Training on Muscular Strength, Hypertrophy, and Muscle Quality in Preconditioned Older Women. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2018, 28, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, C.L.; Dias, C.P.; Radaelli, R.; Massa, J.C.; Bortoluzzi, R.; Schoenell, M.C.; Noll, M.; Alberton, C.L.; Kruel, L.F. Effect of traditional resistance and power training using rated perceived exertion for enhancement of muscle strength, power, and functional performance. Age 2016, 38, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucci, H.T.; Figueiredo, D.S.; de Paula Carvalho, R.; Souza, A.C.F.; Vassão, P.G.; Renno, A.C.M.; Ciol, M.A. Quadriceps femoris performance after resistance training with and without photobiomodulation in elderly women: A randomized clinical trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2019, 34, 1583–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, G.; Feito, Y.; Fountaine, C.; Roy, B.A. (Eds.) ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 11th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019; p. 157. [Google Scholar]

- de Lange, C. Brazil’s Billion-Dollar Gym Experiment. Available online: https://mosaicscience.com/story/brazils-billion-dollar-gym-experiment/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Spiering, B.A.; Mujika, I.; Sharp, M.A.; Foulis, S.A. Maintaining Physical Performance: The Minimal Dose of Exercise Needed to Preserve Endurance and Strength Over Time. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 1449–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cañete, S.; Juan, A.F.S.; Pérez, M.; Gómez-Gallego, F. Does creatine supplementation improve functional capacity in elderly women? J. Strength Cond. Res. 2006, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gotshalk, L.A.; Kraemer, W.J.; Mendonca, M.A.; Vingren, J.L.; Kenny, A.M.; Spiering, B.A.; Volek, J.S. Creatine supplementation improves muscular performance in older women. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 102, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sestili, P.; Martinelli, C.; Colombo, E.; Barbieri, E.; Potenza, L.; Sartini, S.; Fimognari, C. Creatine as an antioxidant. Amino Acids. 2011, 40, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Boit, M.; Sibson, R.; Sivasubramaniam, S.; Meakin, J.R.; Greig, C.A.; Aspden, R.M.; Thies, F.; Jeromson, S.; Hamilton, D.L.; Speakman, J.R.; et al. Sex differences in the effect of fish-oil supplementation on the adaptive response to resistance exercise training in older people: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 105, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devries, M.C.; McGlory, C.; Bolster, D.R.; Kamil, A.; Rahn, M.; Harkness, L.; Baker, S.K.; Phillips, S.M. Leucine, not Total Protein, Content of a Supplement Is the Primary Determinant of Muscle Protein Anabolic Responses in Healthy Older Women. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 1088–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, E.D.; Srivatsan, S.R.; Agrawal, S.; Menon, K.S.; Delmonico, M.J.; Wang, M.Q.; Hurley, B.F. Effects of strength training on physical function: Influence of power, strength, and body composition. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 2627–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smee, D.J.; Berry, H.L.; Anson, J.M.; Waddington, G.S. The relationship between subjective falls-risk assessment tools and functional, health-related, and body composition characteristics. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2017, 36, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.C.; Marra, C.A.; Robertson, M.C.; Khan, K.M.; Najafzadeh, M.; Ashe, M.C.; Liu-Ambrose, T. Economic evaluation of dose-response resistance training in older women: A cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analysis. Osteoporos. Int. 2011, 22, 1355–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).