Characterization of Pectin Extracted from the Peel of Dragon Fruit (Selenicereus cf. guatemalensis ‘Queen Purple’)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

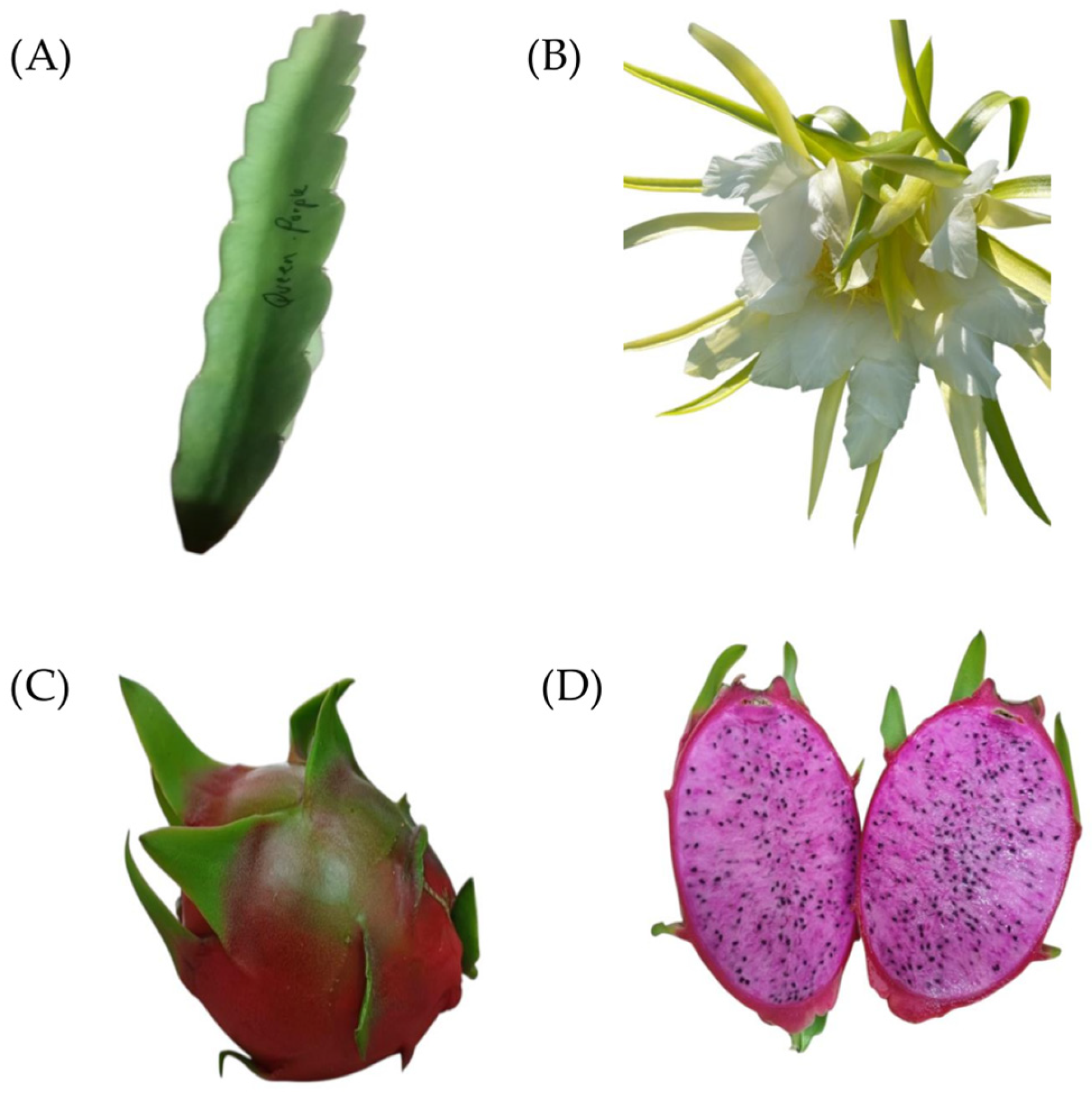

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Pectin Extraction

2.3. Chemical Structure Analysis by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

2.4. Characterization of Pectin from Dragon Fruit Peel

2.4.1. Pectin Yield

2.4.2. Moisture Content

2.4.3. Ash Content

2.4.4. Equivalent Weight (EW)

2.4.5. Methoxyl Content (MeO)

2.4.6. Total Anhydrouronic Acid (AUA) Content

2.4.7. Molecular Weight (Mw)

2.5. Betalain Content

2.6. Antioxidant Capacity of Pectins

2.7. Total Phenol Content (TPC)

2.8. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

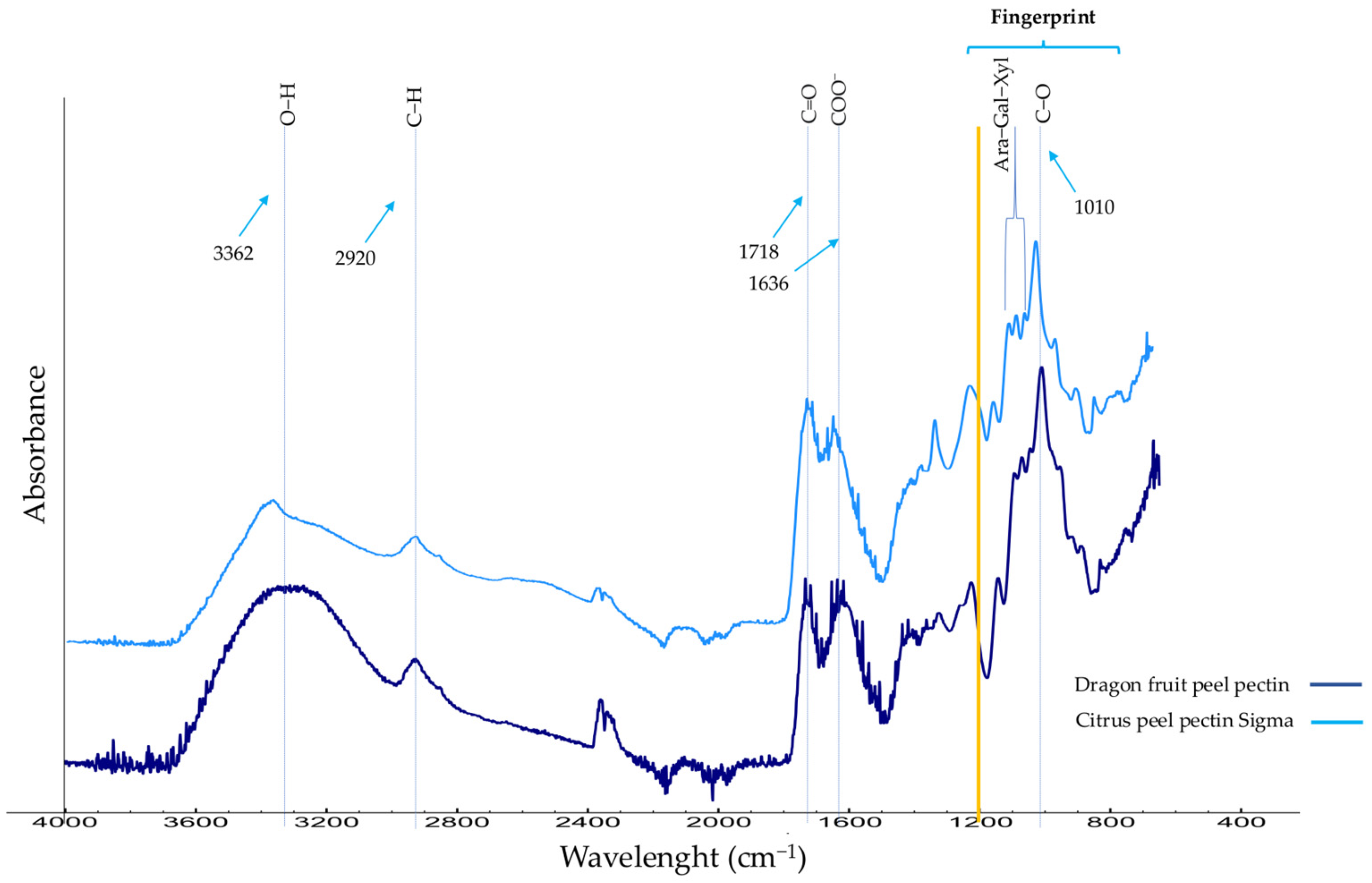

3.1. Chemical Structure Analysis by FT-IR

3.2. Degree of Esterification (DE)

3.3. Pectin Characterization

3.3.1. Pectin Yield

3.3.2. Moisture Content

3.3.3. Ash Content

3.3.4. Equivalent Weight (EW)

3.3.5. Methoxyl Content (MeO)

3.3.6. Total Anhydrouronic Acid (AUA) Content

3.3.7. Molecular Weight (Mw) of Pectins

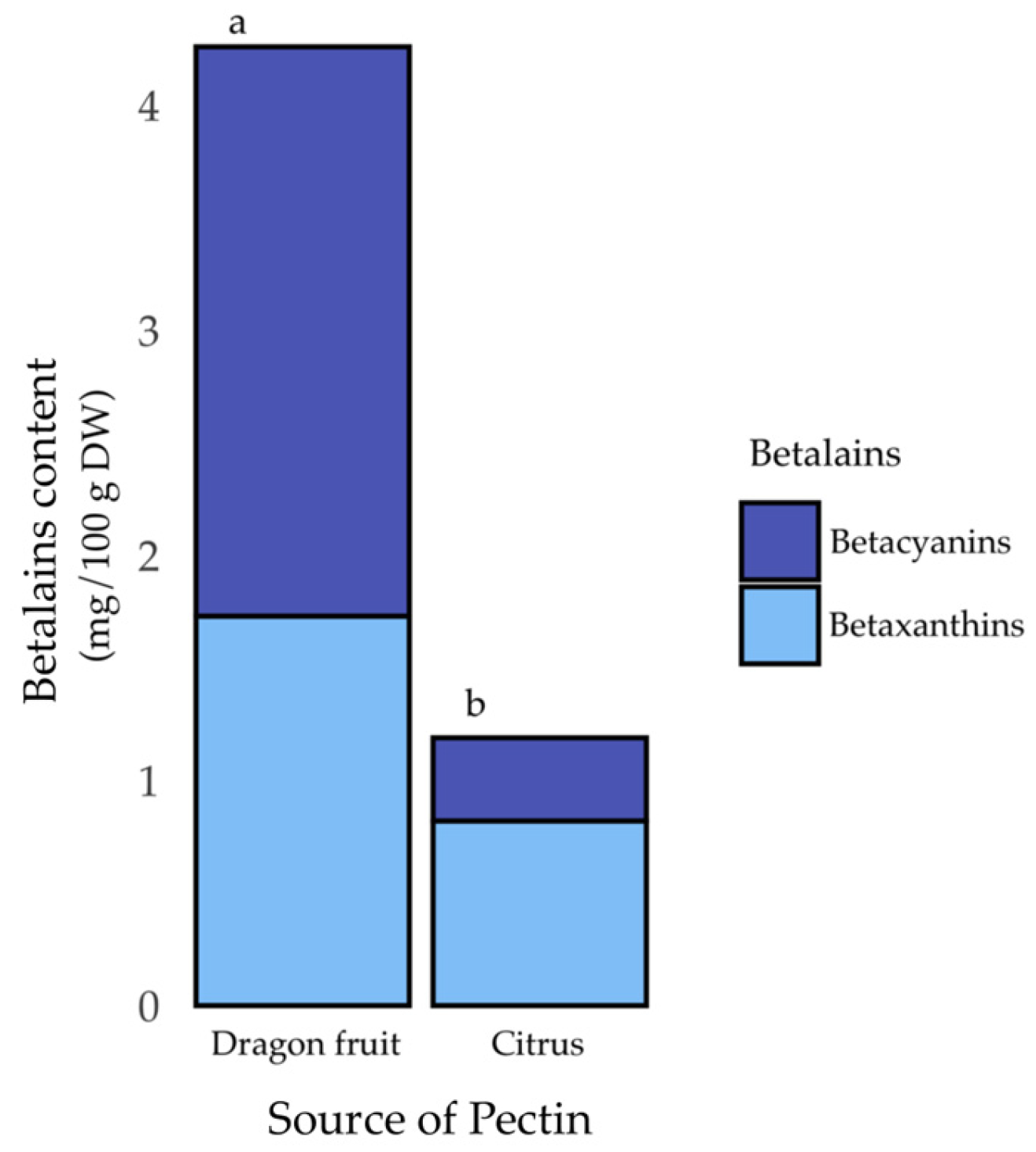

3.4. Betalain Content of Pectins

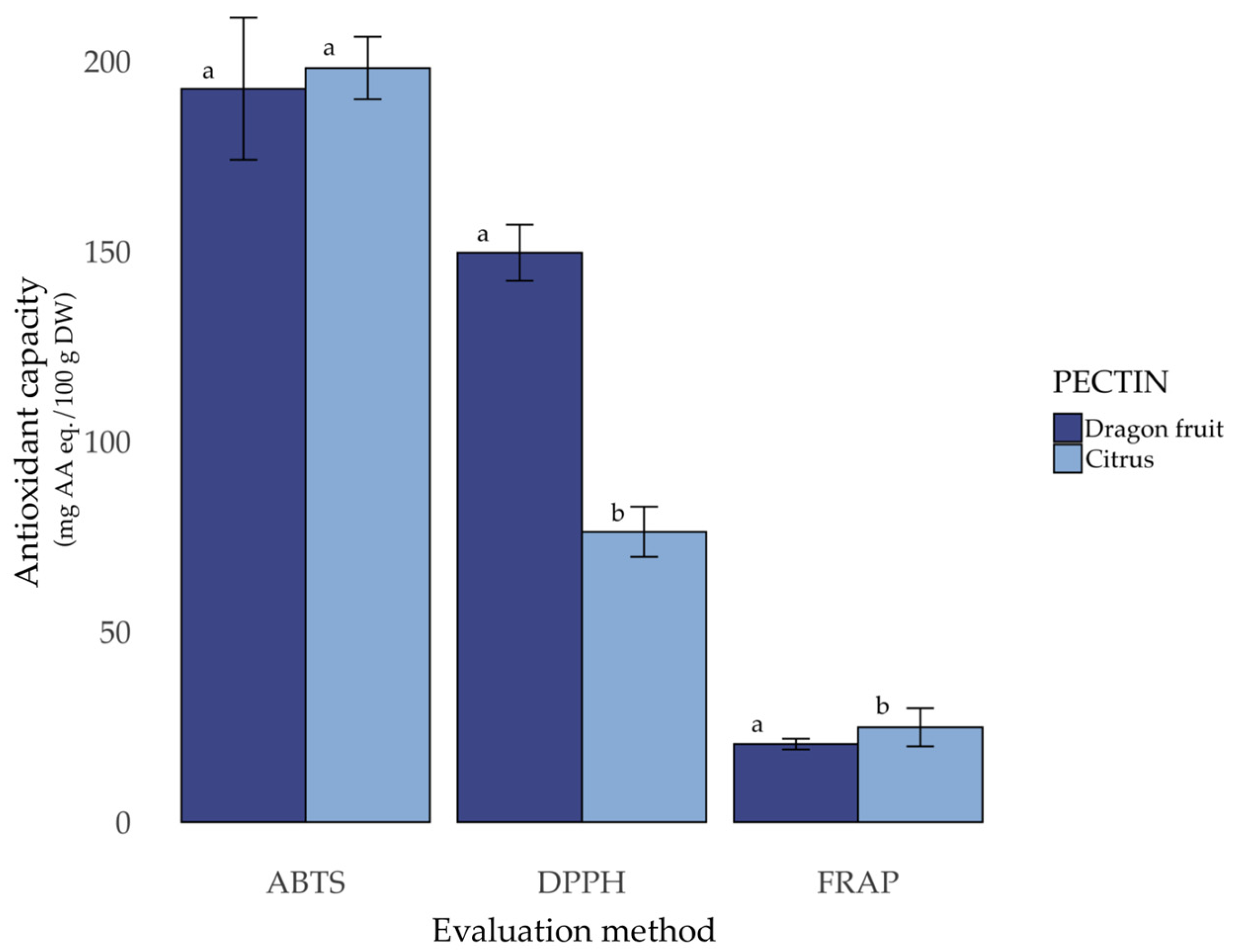

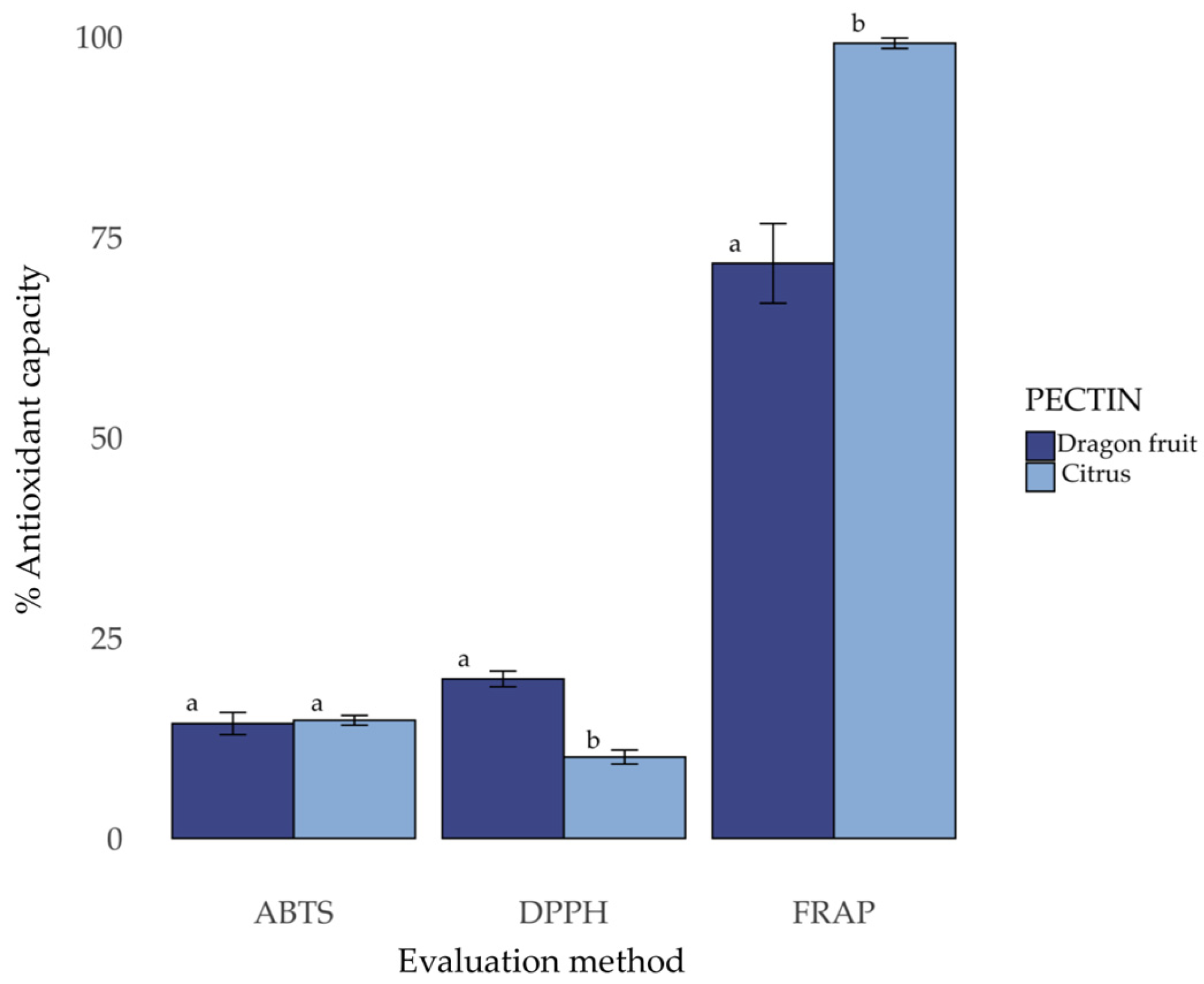

3.5. Antioxidant Capacity of Pectins

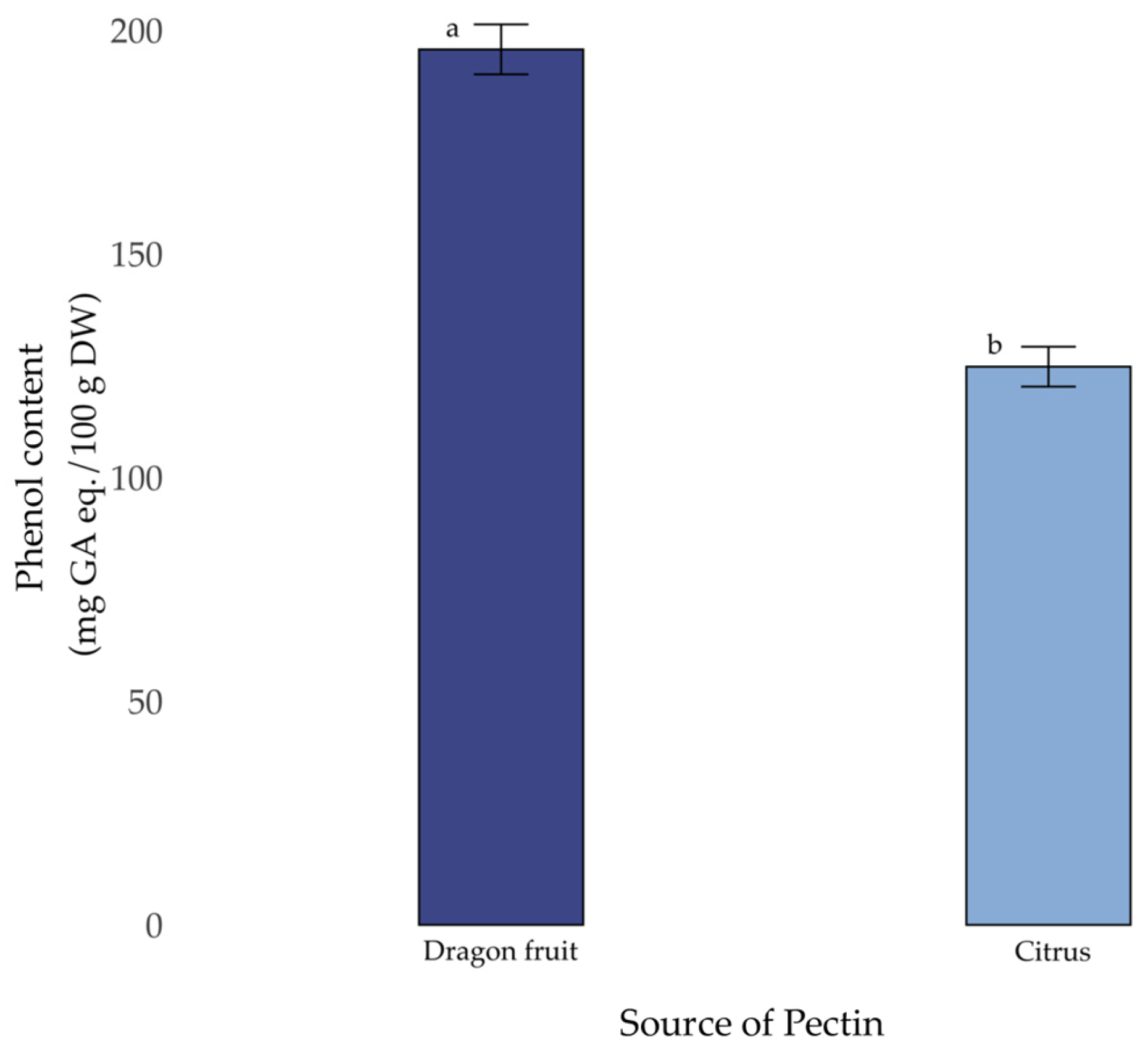

3.6. Total Phenol Content (TPC)

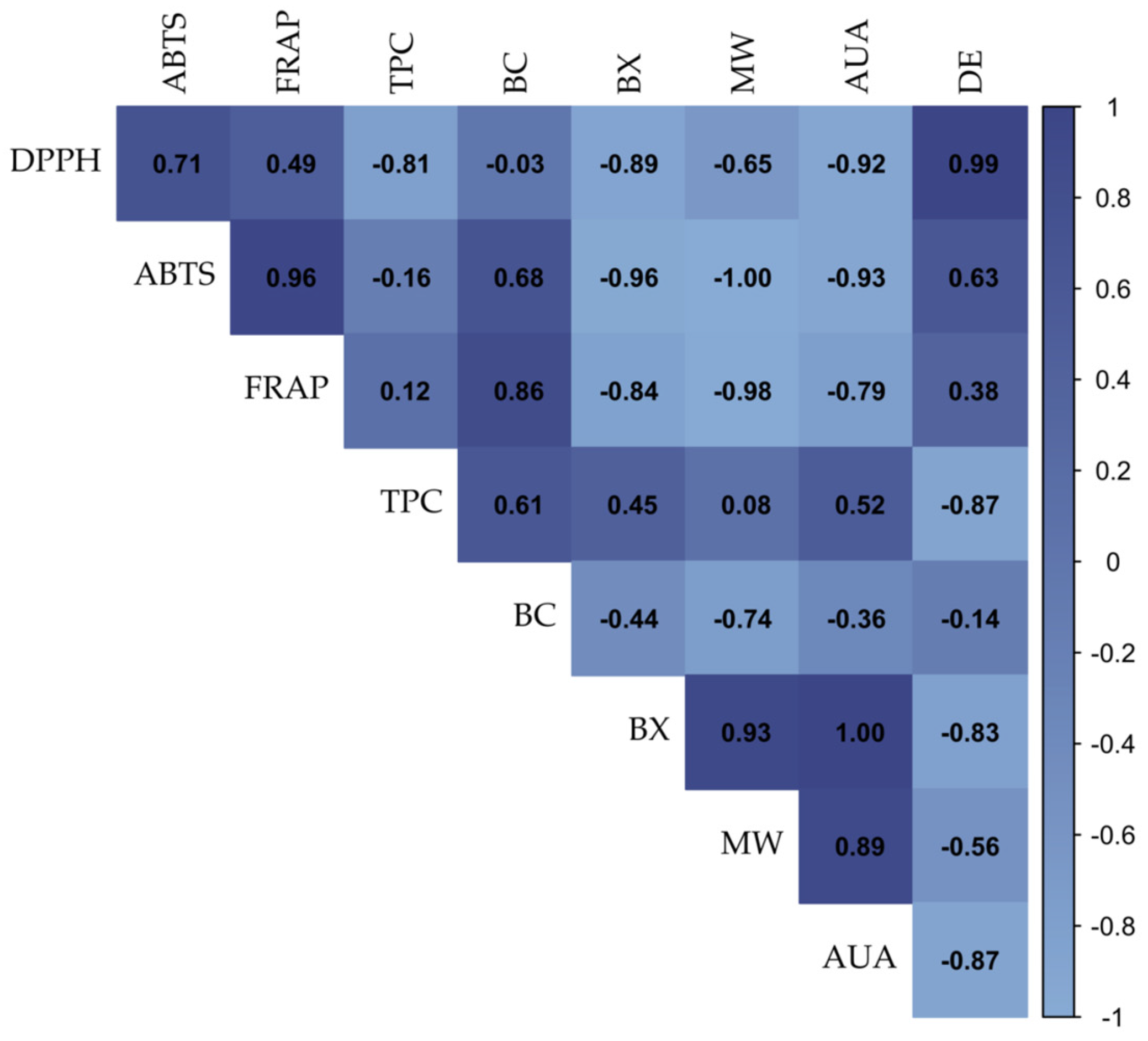

3.7. Correlation Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABTS | 2,2′azinobis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline)-6-sulfonic acid |

| AOAC | Association of Official Analytical Chemists |

| AUA | Anhydrogalacturonic acid content |

| BC | Betacyanin Content |

| BX | Betaxanthin Content |

| DE | Degree of esterification |

| DPPH | 2,2′-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| EAA/100 gDW | Mg ascorbic acid equivalents per 100 g of dry weight |

| EAG/100 gDW | Mg equivalents of gallic acid per 100 g of dry weight |

| EW | Equivalent weight |

| FCC | Food Chemical Codex |

| FRAP | Ferric ion reducing power |

| HMPs | High-methoxyl pectins |

| LMPs | Low-methoxyl pectins |

| MeO | Methoxyl content |

| Mw | Molecular weight |

| TPC | Total Phenol Content |

References

- Liu, L.; Sui, Y.; Wang, T.; Li, X.; Chen, L.; Shi, M. Physicochemical and Antioxidant Properties of Pectin from Actinidia Arguta Sieb.et Zucc (A. arguta) Extracted by Ultrasonic. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1349162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawkowska, D.; Cybulska, J.; Zdunek, A. Structure-Related Gelling of Pectins and Linking with Other Natural Compounds: A Review. Polymers 2018, 10, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aina, V.O.; Barau, M.M.; Mamman, O.A.; Zakari, A.; Haruna, H.; Umar, M.S.H.; Abba, Y.B. Extraction and Characterization of Pectin from Peels of Lemon (Citrus limon), Grape Fruit (Citrus paradisi) and Sweet Orange (Citrus sinensis). Br. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2012, 3, 259–262. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, B.M.N.; Pirak, T. Physicochemical Properties and Antioxidant Activities of White Dragon Fruit Peel Pectin Extracted with Conventional and Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction. Cogent Food Agric. 2019, 5, 1633076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Nisar, T.; Liang, D.; Hou, Y.; Sun, L.; Guo, Y. Low Methoxyl Pectin Gelation under Alkaline Conditions and Its Rheological Properties: Using NaOH as a pH Regulator. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 79, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, C.M.P.; Coimbra, J.S.R.; Souza, V.G.L.; Sousa, R.C.S. Structure and Applications of Pectin in Food, Biomedical, and Pharmaceutical Industry: A Review. Coatings 2021, 11, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, V.; Biswas, D.; Roy, S.; Vaidya, D.; Verma, A.; Gupta, A. Current Advancements in Pectin: Extraction, Properties and Multifunctional Applications. Foods 2022, 11, 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picot-Allain, M.C.N.; Ramasawmy, B.; Emmambux, M.N. Extraction, Characterisation, and Application of Pectin from Tropical and Sub-Tropical Fruits: A Review. Food Rev. Int. 2022, 38, 282–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandee, Y.; Uttapap, D.; Mischnick, P.Y. Ash Content and Structural Composition of Pomelo Peel Pectins Extracted under Acidic and Alkaline Conditions. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 87, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Chen, W.; Yan, T.; Wang, D.; Hou, F.; Miao, S.; Liu, D. Comparison of Citrus Pectin and Apple Pectin in Conjugation with Soy Protein Isolate (SPI) under Controlled Dry-Heating Conditions. Food Chem. 2020, 309, 125501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Fan, Z.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Shi, R. Eco-friendly Extraction and Physicochemical Properties of Pectin from Jackfruit Peel Waste with Subcritical Water. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 5283–5292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafie, M.H.; Yusof, R.; Gan, C.-Y. Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) Mediated Extraction of Pectin from Averrhoa Bilimbi: Optimization and Characterization Studies. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 216, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakooei-Vayghan, R.; Peighambardoust, S.H.; Hesari, J.; Peressini, D. Effects of Osmotic Dehydration (with and without Sonication) and Pectin-Based Coating Pretreatments on Functional Properties and Color of Hot-Air Dried Apricot Cubes. Food Chem. 2020, 311, 125978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, W.; Khan, M.R.; Ahmad, N.; Rhim, J.-W.; Jiang, W.; Roy, S. Film Properties of Pectin Obtained from Various Fruits’ (Lemon, Pomelo, Pitaya) Peels. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coman, V.; Teleky, B.-E.; Mitrea, L.; Martău, G.A.; Szabo, K.; Călinoiu, L.-F.; Vodnar, D.C. Bioactive Potential of Fruit and Vegetable Wastes. In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 91, pp. 157–225. ISBN 978-0-12-820470-2. [Google Scholar]

- Velenturf, A.P.M.; Purnell, P. Principles for a Sustainable Circular Economy. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1437–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, B.L.; Tang, S.F.; Ali, A.; Chow, Y.H. Optimisation of Pectin Production from Dragon Fruit Peels Waste: Drying, Extraction and Characterisation Studies. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalgaonkar, K.; Mahawar, M.K.; Bibwe, B.; Kannaujia, P. Postharvest Profile, Processing and Waste Utilization of Dragon Fruit (Hylocereus spp.): A Review. Food Rev. Int. 2022, 38, 733–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, B.; Ozkan, G.; Kostka, T.; Capanoglu, E.; Esatbeyoglu, T. Valorization and Application of Fruit and Vegetable Wastes and By-Products for Food Packaging Materials. Molecules 2021, 26, 4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez Ramos, L.; García-Mateos, R.; Castillo González, A.M.; Ybarra Moncada, M.C.; Nieto Angel, R. Fruits of the Pitahaya Hylocereus undatus and H. Ocamponis: Nutritional Components and Antioxidants. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2020, 2, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés Orizano, J.A. Especie de Origen Tropical y Sub Tropical: La Pitahaya (Hylocereus guatemalensis) y Sus Sistemas de Conducción. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Agraria la Molina, Lima, Perú, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda Ceja, R. Las Tres “P” de La Pitahaya, Polinización, Poda, Producción. Available online: https://es.slideshare.net/slideshow/curso-de-pitahaya-2020/239812720 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Castillo-Zapata, K.C.; Reyes-Diaz, J.D.; Cornelio-Santiago, H.P.; Espinoza-Espinoza, L.A.; Valdiviezo-Marcelo, J.; Ruiz-Flores, L.A. Efecto del secado con aire caliente en el contenido de fenólicos totales y capacidad antioxidante de la cáscara de pitahaya roja (Hylocereus guatemalensis). Rev. Investig. Univ. Cordon Bleu 2024, 11, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerén López, J.G. Distribución, Etnobotánica Y Cultivo de Pitahaya (Selenicereus, Hylocereeae, Cactaceae) en el Salvador. Master’s Thesis, Colegio de Posgraduados, Montecillo, México, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carpio Rivas, V.; Balois Morales, R.; Ochoa Jiménez, V.A.; Bello Lara, J.E.; Berúmen Varela, G. Parámetros fisicoquímicos y capacidad antioxidante de frutos de pitahaya Queen Purple en almacenamiento poscosecha: Almacenamiento poscosecha en frutos de pitahaya. Rev. Bio Cienc. 2024, 11, e1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegada Franco, V.Y. Extracción de pectina de residuos de cáscara de naranja por hidrólisis ácida asistida por microondas (HMO). Investig. Desarro. 2015, 15, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liew, S.Q.; Ngoh, G.C.; Yusoff, R.; Teoh, W.H. Sequential Ultrasound-Microwave Assisted Acid Extraction (UMAE) of Pectin from Pomelo Peels. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 93, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dranca, F.; Vargas, M.; Oroian, M. Physicochemical Properties of Pectin from Malus Domestica ‘Fălticeni’ Apple Pomace as Affected by Non-Conventional Extraction Techniques. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 100, 105383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 18th ed.; Horwitz, W., AOAC International, Eds.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-935584-77-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ranganna, S. Handbook of Analysis and Quality Control for Fruit and Vegetable Products; Tata McGraw Hill Publishing Company Limited: New Delhi, India, 1986; pp. 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, S.; Hasan, Z. Extraction and Characterisation of Pectin from Various Tropical Agrowastes. Asean Food J. 1995, 10, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zioga, M.; Tsouko, E.; Maina, S.; Koutinas, A.; Mandala, I.; Evageliou, V. Physicochemical and Rheological Characteristics of Pectin Extracted from Renewable Orange Peel Employing Conventional and Green Technologies. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 132, 107887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnier, C.; Axelos, M.A.V.; Thibault, J.-F. Phase Diagrams of Pectin-Calcium Systems: Influence of pH, Ionic Strength, and Temperature on the Gelation of Pectins with Different Degrees of Methylation. Carbohydr. Res. 1993, 240, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutor, K.; Wybraniec, S. Identification and Determination of Betacyanins in Fruit Extracts of Melocactus Species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 11459–11467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandate-Flores, L.; Rodríguez-Hernández, D.V.; Rostro-Alanis, M.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Brambila-Paz, C.; Sosa-Hernández, J.E.; Parra-Saldívar, R.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Evaluation of Three Methods for Betanin Quantification in Fruits from Cacti. MethodsX 2022, 9, 101746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a Free Radical Method to Evaluate Antioxidant Activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stintzing, F.C.; Herbach, K.M.; Mosshammer, M.R.; Carle, R.; Yi, W.; Sellappan, S.; Akoh, C.C.; Bunch, R.; Felker, P. Color, Betalain Pattern, and Antioxidant Properties of Cactus Pear (Opuntia spp.) Clones. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawuyi, I.F.; Kim, S.R.; Lee, W.Y. Application of Plant Mucilage Polysaccharides and Their Techno-Functional Properties’ Modification for Fresh Produce Preservation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 272, 118371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Dai, J.; Cui, H.; Lin, L. Edible Films of Pectin Extracted from Dragon Fruit Peel: Effects of Boiling Water Treatment on Pectin and Film Properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 147, 109324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambuza, A.; Rungqu, P.; Oyedeji, A.O.; Miya, G.M.; Kuria, S.K.; Hosu, S.Y.; Oyedeji, O.O. Extraction, Characterization, and Antioxidant Activity of Pectin from Lemon Peels. Molecules 2024, 29, 3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatjigakis, A.K.; Pappas, C.; Proxenia, N.; Kalantzi, O.; Rodis, P.; Polissiou, M. FT-IR Spectroscopic Determination of the Degree of Esterification of Cell Wall Pectins from Stored Peaches and Correlation to Textural Changes. Carbohydr. Polym. 1998, 37, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Qin, D.; Li, H.; Guo, D.; Cheng, H.; Sun, J.; Huang, M.; Ye, X.; Sun, B. Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Lycium Ruthenicum Pectin by Different Extraction Methods. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 946606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Renard, C.M.G.C.; Bureau, S.; Le Bourvellec, C. Revisiting the Contribution of ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy to Characterize Plant Cell Wall Polysaccharides. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 262, 117935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Q.; Shu, C.; Zhang, T.; Cao, J. Non-Methylesterified Pectin from Pitaya (Hylocereus undatus) Fruit Peel: Optimization of Extraction and Nanostructural Characterization. Food Innov. Adv. 2024, 3, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, A.; Dominiak, M.; Vidal-Melgosa, S.; Willats, W.G.T.; Søndergaard, K.M.; Hansen, P.W.; Meyer, A.S.; Mikkelsen, J.D. Prediction of Pectin Yield and Quality by FTIR and Carbohydrate Microarray Analysis. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2017, 10, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozioł, A.; Środa-Pomianek, K.; Górniak, A.; Wikiera, A.; Cyprych, K.; Malik, M. Structural Determination of Pectins by Spectroscopy Methods. Coatings 2022, 12, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivamathi, C.S.; Gunaseelan, S.; Soosai, M.R.; Vignesh, N.S.; Varalakshmi, P.; Kumar, R.S.; Karthikumar, S.; Kumar, R.V.; Baskar, R.; Rigby, S.P.; et al. Process Optimization and Characterization of Pectin Derived from Underexploited Pineapple Peel Biowaste as a Value-Added Product. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 123, 107141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidel, D.N.A.; Rashid, J.M.; Hamidon, N.H.; Salleh, L.M.; Kassim, A.S.M. Extraction and Characterization of Pectin from Dragon Fruit (Hylocereus polyrhizus) Peels. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2017, 56, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Olawuyi, I.F.; Said, N.S.; Lee, W.-Y. Comparative Analysis of Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Pectin from Extracted Dragon Fruit Waste by Different Techniques. Polymers 2024, 16, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinde, G.B.; Swami, S.B.; Zambre, S.; Venkatesh, K.; Pardeshi, I.; Patange, S. Effect of Maturity Levels and Blanching Temperature on Extraction of Pectin from Jackfruit Rags and Study Its Properties. Int. J. Adv. Biochem. Res. 2024, 8, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, R.; Nahar, K.; Zohora, F.T.; Islam, M.; Bhuiyan, R.H.; Jahan, M.S.; Shaikh, A.A. Pectin from Lemon and Mango Peel: Extraction, Characterisation and Application in Biodegradable Film. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2022, 4, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.S. Aqueous Extraction of Pectin from Sour Orange Peel and Its Preliminary Physicochemical Properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 82, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, R.M.; Mishra, P.; Tabassum, S.; Wahid, Z.A.; Sakinah, A.M.M. High Methoxyl Pectin Extracts from Hylocereus polyrhizus’s Peels: Extraction Kinetics and Thermodynamic Studies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 141, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, K.; Zahari, N.I.M.; Gannasin, S.P.; Zahari, N.I.M.; Bakar, J. High Methoxyl Pectin from Dragon Fruit (Hylocereus polyrhizus) Peel. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 42, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, D.; Panesar, P.S.; Chopra, H.K. Green Extraction of Pectin from Citrus Limetta Peels Using Organic Acid and Its Characterization. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodsamran, P.; Sothornvit, R. Microwave Heating Extraction of Pectin from Lime Peel: Characterization and Properties Compared with the Conventional Heating Method. Food Chem. 2019, 278, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Ozukum, R.; Mathad, G.M. Extraction, Characterization and Utilization of Pectin from Apple Peels. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2020, 9, 2599–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.H.F.; Oliveira, T.Í.S.; Rosa, M.F.; Cavalcante, F.L.; Moates, G.K.; Wellner, N.; Waldron, K.W.; Azeredo, H.M.C. Pectin Extraction from Pomegranate Peels with Citric Acid. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 88, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girma, E.; Worku, M.T. Extraction and Characterization of Pectin from Selected Fruit Peel Waste. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2016, 6, 447–454. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad, N.W.F.; Nurrulhidayah, A.F.; Hamzah, M.S.; Rashidi, O.; Rohman, A. Physicochemical Properties of Dragon Fruit Peel Pectin and Citrus Peel Pectin: A Comparison. Food Res. 2020, 4, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Chemical Codex, 5th ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003.

- Ismail, N.S.M.; Ramli, N.; Hani, N.M.; Meon, Z. Extraction and Characterization of Pectin from Dragon Fruit (Hylocereus polyrhizus) Using Various Extraction Conditions. Sains Malays. 2012, 41, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kute, A.B.; Mohapatra, D.; Kotwaliwale, N.; Giri, S.K.; Sawant, B.P. Characterization of Pectin Extracted from Orange Peel Powder Using Microwave-Assisted and Acid Extraction Methods. Agric. Res. 2020, 9, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Biswas, M.M.H.; Esham, M.K.H.; Roy, P.; Khan, R.; Hasan, S.M.K. Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) by-Products a Novel Source of Pectin: Studies on Physicochemical Characterization and Its Application in Soup Formulation as a Thickener. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 2, 100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkaew, M.; Sommano, S.R.; Tangpao, T.; Rachtanapun, P.; Jantanasakulwong, K. Mango Peel Pectin by Microwave-Assisted Extraction and Its Use as Fat Replacement in Dried Chinese Sausage. Foods 2020, 9, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M.; Singh, S.; Chauhan, A.K. A Comparative Study of the Extraction of Pectin from Kinnow (Citrus reticulata) Peel Using Different Techniques. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2023, 16, 2272–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J.; Gómez, K.; Vega, L. Optimization and Preliminary Physicochemical Characterization of Pectin Extraction from Watermelon Rind (Citrullus lanatus) with Citric Acid. Int. J. Food Sci. 2022, 2022, 3068829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, S.Y.; Choo, W.S.; Young, D.J.; Loh, X.J. Pectin as a Rheology Modifier: Origin, Structure, Commercial Production and Rheology. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 161, 118–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mugampoza, D.; Gafuma, S.; Kyosaba, P.; Namakajjo, R. Characterization of Pectin from Pulp and Peel of Ugandan Cooking Bananas at Different Stages of Ripening. J. Food Res. 2020, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Li, D. Pectin Extracted from Dragon Fruit Peel: An Exploration as a Natural Emulsifier. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 221, 976–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ma, F.; Li, R.; Ren, G.; Yan, D.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, X.; Wu, R.; Wu, J. Degradation of Tremella Fuciformis Polysaccharide by a Combined Ultrasound and Hydrogen Peroxide Treatment: Process Parameters, Structural Characteristics, and Antioxidant Activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 160, 979–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Hua, Q.; Chen, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, J.; Hu, G.; Zhao, J.; et al. Transcriptomics-Based Identification and Characterization of Glucosyltransferases Involved in Betalain Biosynthesis in Hylocereus Megalanthus. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 152, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.P.; Nguyen, L.P.U.; Le, D.T.; Tran, T.Y.N.; Huynh, P.X. Effects of Pectinase Treatment on the Quality of Red Dragon Fruit (Hylocereus polyrhizus) Juice. Int. Food Res. J. 2023, 30, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, E.O.; Prieto, A.C. La pitahaya (Hylocereus spp.) como alimento funcional: Fuente de nutrientes y fitoquímicos. Milen. Cienc. Y Arte 2023, 21, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ramos, L. Integrated Postharvest of Pitahaya Fruits (Hylocereus ocamponis) Stored at Different Temperatures. J. Prof. Assoc. Cactus Dev. 2023, 25, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Dragon Fruit Peel Pectin | Citrus Peel Pectin |

|---|---|---|

| Yield (%) | 12.8 | ---- |

| Moisture Content (%) | 9.90 | 10.90 |

| Ash content (%) | 8.26 | 6.62 |

| Equivalent weight (g/eq.) | 274.01 | 1072.12 |

| Methoxyl content (%) | 5.99 | 7.18 |

| Total anhydrouronic acid content (%) | 98.27 | 57.20 |

| Molecular Weight (kDa) | 645 | ---- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carpio-Rivas, V.; Balois-Morales, R.; Ochoa-Jiménez, V.A.; Bello-Lara, J.E.; Tafolla-Arellano, J.C.; Berumen-Varela, G. Characterization of Pectin Extracted from the Peel of Dragon Fruit (Selenicereus cf. guatemalensis ‘Queen Purple’). Polysaccharides 2025, 6, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040098

Carpio-Rivas V, Balois-Morales R, Ochoa-Jiménez VA, Bello-Lara JE, Tafolla-Arellano JC, Berumen-Varela G. Characterization of Pectin Extracted from the Peel of Dragon Fruit (Selenicereus cf. guatemalensis ‘Queen Purple’). Polysaccharides. 2025; 6(4):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040098

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarpio-Rivas, Victoria, Rosendo Balois-Morales, Verónica Alhelí Ochoa-Jiménez, Juan Esteban Bello-Lara, Julio César Tafolla-Arellano, and Guillermo Berumen-Varela. 2025. "Characterization of Pectin Extracted from the Peel of Dragon Fruit (Selenicereus cf. guatemalensis ‘Queen Purple’)" Polysaccharides 6, no. 4: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040098

APA StyleCarpio-Rivas, V., Balois-Morales, R., Ochoa-Jiménez, V. A., Bello-Lara, J. E., Tafolla-Arellano, J. C., & Berumen-Varela, G. (2025). Characterization of Pectin Extracted from the Peel of Dragon Fruit (Selenicereus cf. guatemalensis ‘Queen Purple’). Polysaccharides, 6(4), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040098