Changed Characteristics of Bacterial Cellulose Due to Its In Situ Biosynthesis as a Part of Composite Materials

Abstract

1. Introduction

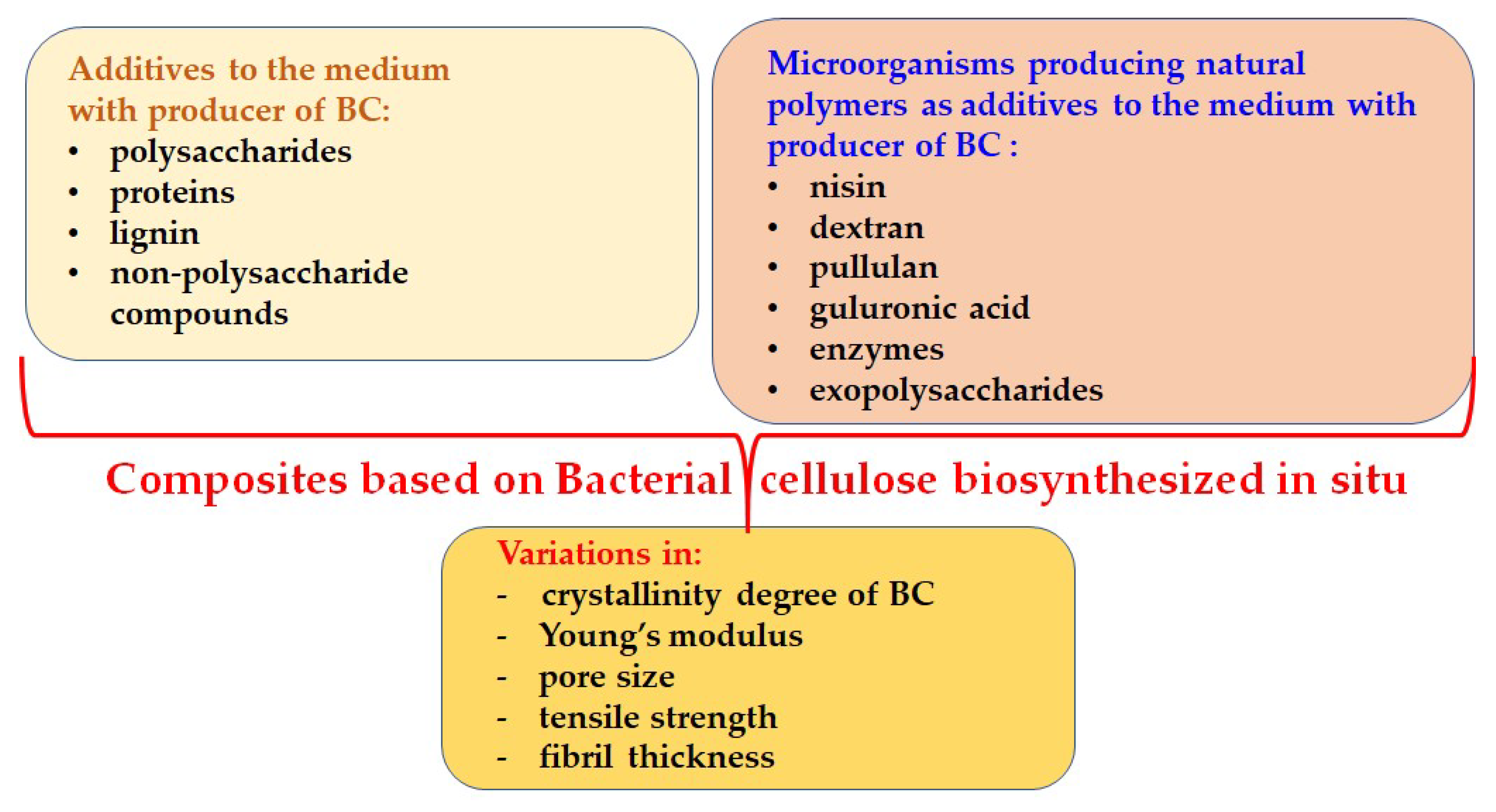

2. Approaches to Obtaining New BC-Based Composites in the Framework of Polymer Biosynthesis

2.1. The BC—Polysaccharide Composites

2.2. The BC—Non-Polysaccharide Composites

2.3. Production of BC Composites Through Co-Cultivation/Addition of Different Microorganisms Producing Specific Compounds

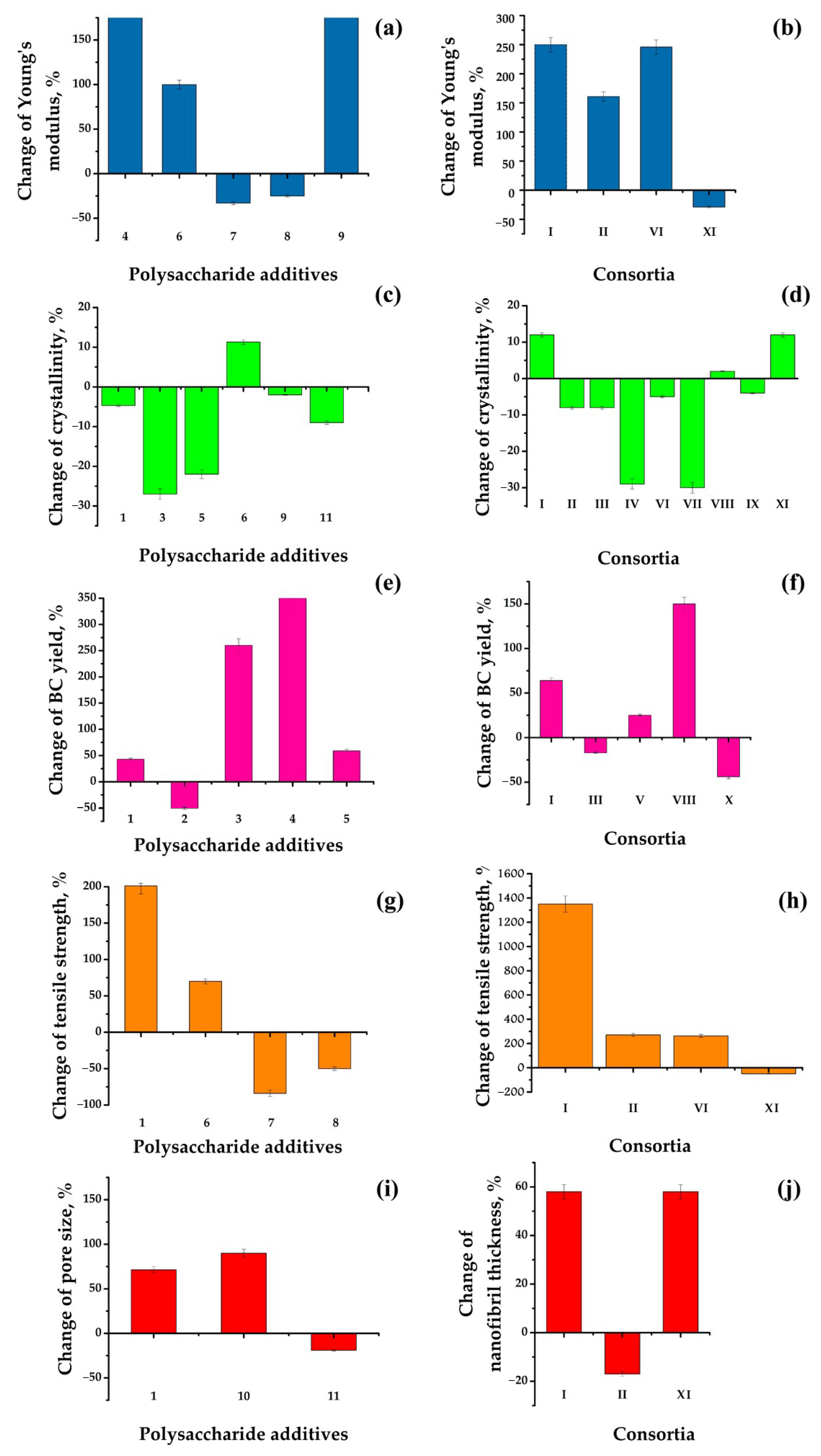

3. Comparative Analysis of In Situ Synthesized BC Composites Through Various Modes

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AX | Arabinoxylan |

| BC | Bacterial cellulose |

| CFUs | Colony-forming units |

| CMC | Carboxymethyl cellulose |

| 6CF-Glc | 6-carboxyfluorescein-glucose |

| EMI | Electromagnetic interference |

| EPS | Exopolysaccharides |

| GA | Guluronic acid |

| GNPs | Gold nanoparticles |

| GO | Graphene oxide |

| PHBs | Polyhydroxybutyrates |

| RGO | Reduced form of Graphene oxide |

| TEOS | Tetraethyl orthosilicate |

| TMOS | Tetramethyl orthosilicate |

| UV | Ultra-violet |

| XG | Xyloglucan |

References

- Girard, V.D.; Chaussé, J.; Vermette, P. Bacterial cellulose: A comprehensive review. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Singh, P.K.; Pattnaik, R.; Kumar, S.; Ojha, S.K.; Srichandan, H.; Parhi, P.K.; Jyothi, R.K.; Sarangi, P.K. Biochemistry, synthesis, and applications of bacterial cellulose: A review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 780409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potočnik, V.; Gorgieva, S.; Trček, J. From Nature to Lab: Sustainable bacterial cellulose production and modification with synthetic biology. Polymers 2023, 15, 3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andriani, D.; Apriyana, A.Y.; Karina, M. The optimization of bacterial cellulose production and its applications: A review. Cellulose 2020, 27, 6747–6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustina, W.; Boontawan, A.; Gamonpilas, C.; Prakit Sukyai, P.; Yamabhai, M. Recent studies and industrial applications of bacterial nanocellulose in the food industry. Cellulose 2025, 32, 8729–8756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikbakht, A.; van Zyl, E.M.; Larson, S.; Fenlon, S.; Coburn, J.M. Bacterial cellulose purification with non-conventional, biodegradable surfactants. Polysaccharides 2024, 5, 857–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, L.; Deng, Y.; Wei, Q. Research progress of the biosynthetic strains and pathways of bacterial cellulose. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 49, kuab071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płoska, J.; Garbowska, M.; Klempová, S.; Stasiak-Różańska, L. Obtaining bacterial cellulose through selected strains of acetic acid bacteria in classical and waste media. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netrusov, A.I.; Liyaskina, E.V.; Kurgaeva, I.V.; Liyaskina, A.U.; Yang, G.; Revin, V.V. Exopolysaccharides producing bacteria: A Review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, M.A.; Flor-Unda, O.; Avila, A.; Garcia, M.D.; Cerda-Mejía, L. Advances in bacterial cellulose production: A scoping review. Coatings 2024, 14, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouro, C.; Gomes, A.P.; Gouveia, I.C. Microbial exopolysaccharides: Structure, diversity, applications, and future frontiers in sustainable functional materials. Polysaccharides 2024, 5, 241–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanot, A.; Tiwari, S.; Purnell, P.; Omar, A.M.; Ribul, M.; Upton, D.J.; Eastmond, H.; Badruddin, I.J.; Walker, H.F.; Gatenby, A.; et al. Demonstrating a biobased concept for the production of sustainable bacterial cellulose from mixed textile, agricultural and municipal wastes. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 486, 144418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanov, N.; Efremenko, E. “Deceived” Concentrated immobilized cells as biocatalyst for intensive bacterial cellulose production from various sources. Catalysts 2018, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revin, V.V.; Liyaskina, E.V.; Parchaykina, M.V.; Kurgaeva, I.V.; Efremova, K.V.; Novokuptsev, N.V. Production of bacterial exopolysaccharides: Xanthan and bacterial cellulose. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhsa, P.; Narain, R.; Manuspiya, H. Physical structure variations of bacterial cellulose produced by different Komagataeibacter xylinus strains and carbon sources in static and agitated conditions. Cellulose 2018, 25, 1571–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efremenko, E.; Senko, O.; Maslova, O.; Stepanov, N.; Aslanli, A.; Lyagin, I. Biocatalysts in synthesis of microbial polysaccharides: Properties and development trends. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Huang, X.; Liu, H.; Lian, H.; Xu, B.; Zhang, W.; Sun, X.; Wang, W.; Jia, S.; Zhong, C. Improvement in bacterial cellulose production by co-culturing Bacillus cereus and Komagataeibacter xylinus. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 313, 120892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Song, Z.; Hao, Y.; Hu, X.; Lin, X.; Liu, S.; Li, C. Effect of co-culture of Komagataeibacter nataicola and selected Lactobacillus fermentum on the production and characterization of bacterial cellulose. LWT 2023, 173, 114224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Singh, A.; Singh, M.K. Novel low-cost green method for production bacterial cellulose. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 6721–6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Singh, A.; Singh, M.K. Green synthesis and optimization of bacterial cellulose production from food industry by-products by response surface methodolgy. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 16965–16998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyagin, I.; Maslova, O.; Stepanov, N.; Presnov, D.; Efremenko, E. Assessment of composite with fibers as a support for antibacterial nanomaterials: A case study of bacterial cellulose, polylactide and usual textile. Fibers 2022, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.L.d.B.; Luz, E.P.C.G.; Castro-Silva, I.I.; Monteiro, R.R.d.C.; Andrade, F.K.; Vieira, R.S. Composite based on biomineralized oxidized bacterial cellulose with strontium apatite for bone regeneration. Polysaccharides 2025, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Ren, Y.; Fang, K.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, A. Preparation, characterization and biocompatibility of chitosan/TEMPO-oxidized bacterial cellulose composite film for potential wound dressing applications. Fibers Polym. 2021, 22, 1790–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, T.; Allain, J.P.; Jaramillo, C.; Restrepo, A.M. Surface modification of bacterial cellulose for biomedical applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslanli, A.; Lyagin, I.; Stepanov, N.; Presnov, D.; Efremenko, E. Bacterial cellulose containing combinations of antimicrobial peptides with various QQ enzymes as a prototype of an “enhanced antibacterial” dressing: In silico and in vitro data. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazón, P.; Vázquez, M. Improving bacterial cellulose films by ex-situ and in-situ modifications: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 113, 106514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslanli, A.; Stepanov, N.; Razheva, T.; Podorozhko, E.A.; Lyagin, I.; Lozinsky, V.I.; Efremenko, E. Enzymatically functionalized composite materials based on nanocellulose and poly(vinyl alcohol) cryogel and possessing antimicrobial activity. Materials 2019, 12, 3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Sadaf, A.; Dubey, S.; Singh, R.P.; Khare, S.K. Production and characterization of Komagataeibacter xylinus SGP8 nanocellulose and its calcite based composite for removal of Cd ions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 46423–46430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.A.; Alfred, M.; Lv, P.; Zhou, H.; Wei, Q. Three-dimensional bacterial cellulose-electrospun membrane hybrid structures fabricated through in-situ self-assembly. Cellulose 2018, 25, 6823–6830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.A.; Lv, P.; Zhou, H.; Naveed, T.; Wei, Q. A Novel In situ self-assembling fabrication method for bacterial cellulose-electrospun nanofiber hybrid structures. Polymers 2018, 10, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.; Gauba, P.; Mathur, G. Bacterial cellulose based composites: Recent trends in production methods and applications. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2024, 58, 799–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, K.; Netravali, A. In situ produced bacterial cellulose nanofiber-based hybrids for nanocomposites. Fibers 2017, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Khumsupan, D.; Lin, S.P.; Santoso, S.P.; Hsu, H.Y.; Cheng, K.C. Production of bacterial cellulose (BC)/nisin composite with enhanced antibacterial and mechanical properties through co-cultivation of Komagataeibacter xylinum and Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 258, 128977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liyaskina, E.V.; Revin, V.V.; Paramonova, E.N.; Revina, N.V.; Kolesnikova, S.G. Bacterial cellulose/alginate nanocomposite for antimicrobial wound dressing. KnE Energy Phys. 2018, 3, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, L.; Jiang, J. An in-situ fabrication of bamboo bacterial cellulose/sodium alginate nanocomposite hydrogels as carrier materials for controlled protein drug delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 170, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Park, S.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.J.; Yang, Y.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Jung, S.K.; Kan, E.; Lee, S.H. Alginate/bacterial cellulose nanocomposite beads prepared using Gluconacetobacter xylinus and their application in lipase immobilization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 157, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.L.; Jia, H.P.; Chen, K.H.; Wu, F.F.; Gao, J.; Hu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Huang, C. Effect of in-situ biochemical modification on the synthesis, structure, and function of xanthan gum based bacterial cellulose generated from Tieguanyin oolong tea residue hydrolysate. Food Chem. 2024, 432, 137133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, M.; Ma, T.; Li, G. In situ production of bacterial cellulose/xanthan gum nanocomposites with enhanced productivity and properties using Enterobacter sp. FY-07. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 248, 116788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Catchmark, J.M.; Demirci, A. Effects of pullulan additive and co-culture of Aureobasidium pullulans on bacterial cellulose produced by Komagataeibacter hansenii. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 45, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Wang, X.; Huo, M.; Zhai, X.; Li, F.; Zhong, C. Preparation and characterization of a novel bacterial cellulose/chitosan bio-hydrogel. Nanomater. Nanotechnol. 2017, 7, 1847980417707172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, S.; Chai, S.; Wei, J.; Zhong, L.; He, Y.; Xue, J. Bacteriostatic activity and cytotoxicity of bacterial cellulose-chitosan film loaded with in-situ synthesized silver nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 281, 119017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.P.; Li, B.; Sun, M.Y.; Wahid, F.; Zhang, H.M.; Wang, S.J.; Xie, Y.Y.; Jia, S.R.; Zhong, C. In situ regulation of bacterial cellulose networks by starch from different sources or amylose/amylopectin content during fermentation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 195, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymańska-Chargot, M.; Chylińska, M.; Cybulska, J.; Kozioł, A.; Pieczywek, P.M.; Zdunek, A. Simultaneous influence of pectin and xyloglucan on structure and mechanical properties of bacterial cellulose composites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 174, 970–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-García, J.C.; Corbin, K.R.; Hussain, H.; Gabrielli, V.; Koev, T.; Iuga, D.; Round, A.N.; Mikkelsen, D.; Gunning, P.A.; Warren, F.J.; et al. High molecular weight mixed-linkage glucan as a mechanical and hydration modulator of bacterial cellulose: Characterization by advanced NMR spectroscopy. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 4180–4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.A.; Siddiqui, Q.; Mushtaq, M.; Farooq, A.; Pang, Z.; Wei, Q. In-situ self-assembly of bacterial cellulose on banana fibers extracted from peels. J. Nat. Fibers 2019, 17, 1317–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Chen, Y.; Huang, J.; Lv, P.; Hussain, T.; Wei, Q. In situ formed active and intelligent bacterial cellulose/cotton fiber composite containing curcumin. Cellulose 2020, 27, 9371–9382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima Fontes, M.; Meneguin, A.B.; Tercjak, A.; Gutierrez, J.; Cury, B.S.F.; Dos Santos, A.M.; Ribeiro, S.J.L.; Barud, H.S. Effect of in situ modification of bacterial cellulose with carboxymethylcellulose on its nano/microstructure and methotrexate release properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 179, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, P.A.; Liu, Y.C.; Hsu, F.Y. Enhancement of the mechanical and hydration properties of biomedical-grade bacterial cellulose using Laminaria japonica extract. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 308, 142688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numata, Y.; Yoshihara, S.; Kono, H. In situ formation and post-formation treatment of bacterial cellulose/κ-carrageenan composite pellicles. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2021, 2, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Huang, T.Y.; Li, Z.X.; Huang, Z.Y.; Lu, Y.Q.; Gao, J.; Hu, Y.; Huang, C. In-situ fermentation with gellan gum adding to produce bacterial cellulose from traditional Chinese medicinal herb residues hydrolysate. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 270, 118350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Catchmark, J.M. Effects of exopolysaccharides from Escherichia coli ATCC 35860 on the mechanical properties of bacterial cellulose nanocomposites. Cellulose 2018, 25, 2273–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasaribu, K.M.; Ilyas, S.; Tamrin, T.; Radecka, I.; Swingler, S.; Gupta, A.; Gea, S. Bioactive bacterial cellulose wound dressings for burns with collagen in-situ and chitosan ex-situ impregnation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 230, 123118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keskin, Z.; Urkmez, A.S.; Hames, E.E. Novel keratin modified bacterial cellulose nanocomposite production and characterization for skin tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 75, 1144–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Mittal, M.; Sharma, R.; Yadav, A.; Aggarwal, N.K. Development of bacterial cellulose-based nanocomposites incorporated with lignin and MgO as a novel antimicrobial wound-dressing material. Iran Polym. J. 2025, 34, 2033–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Dong, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Guo, R.; Zuo, G.; Ye, M.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Wan, Y. Constructing 3D bacterial cellulose/graphene/polyaniline nanocomposites by novel layer-by-layer in situ culture toward mechanically robust and highly flexible freestanding electrodes for supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 1148–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbina, L.; Eceiza, A.; Gabilondo, N.; Corcuera, M.Á.; Retegi, A. Tailoring the in situ conformation of bacterial cellulose-graphene oxide spherical nanocarriers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 163, 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, P.; Pratto, B.; Cruz, A.J.G.; Bankar, S. Valorization of sugarcane straw to produce highly conductive bacterial cellulose/graphene nanocomposite films through in situ fermentation: Kinetic analysis and property evaluation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 238, 117859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, P.; Etula, J.; Bankar, S.B. In situ bioprocessing of bacterial cellulose with graphene: Percolation network formation, kinetic analysis with physicochemical and structural properties assessment. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2019, 2, 4052–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhope, P.C.G.; Loh, J.; Gilmour, K.A.; Zhang, M.; Xie, M.; Dade-Robertson, M.; Jiang, Y. Silicon-infused bacterial cellulose: In situ bioprocessing for tailored strength and surface characteristics. Cellulose 2024, 31, 6663–6679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelraof, M.; Hasanin, M.S.; Farag, M.M.; Ahmed, H.Y. Green synthesis of bacterial cellulose/bioactive glass nanocomposites: Effect of glass nanoparticles on cellulose yield, biocompatibility and antimicrobial activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 138, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayir, E.; Bilgi, E.; Hames, E.E.; Sendemir, A. Production of hydroxyapatite–bacterial cellulose composite scaffolds with enhanced pore diameters for bone tissue engineering applications. Cellulose 2019, 26, 9803–9817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.K.; Tolba, E.; Salama, A. In situ development of bacterial cellulose/hydroxyapatite nanocomposite membrane based on two different fermentation strategies: Characterization and cytotoxicity evaluation. Biomass Convers. Bioref. 2024, 14, 18857–18867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcioglu, N.H. Propolis: As an additive in bacterial cellulose production. Celal Bayar Univ. J. Sci. 2024, 20, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.S.S.; Aris, F.A.F.; Azmi, S.N.N.S.; John, J.H.S.A.; Anuar, N.N.K.; Asnawi, A.S.F.M. Development and evaluation of ciprofloxacin-bacterial cellulose composites produced through in situ incorporation method. Biotechnol. Rep. 2022, 34, e00726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tang, J.; Huang, J.; Hui, M. Production and characterization of bacterial cellulose membranes with hyaluronic acid and silk sericin. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 195, 111273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadakar Sarkandi, A.; Montazer, M.; Harifi, T.; Mahmoudi Rad, M. Innovative preparation of bacterial cellulose/silver nanocomposite hydrogels: In situ green synthesis, characterization, and antibacterial properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, 49824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Ye, Q.; Dong, J.; Li, L.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Jiang, Q. Biofabrication of natural Au/bacterial cellulose hydrogel for bone tissue regeneration via in-situ fermentation. Smart Mater. Med. 2023, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Liao, S.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, J.; Wei, Q.; Ghiladi, R.A.; Wang, Q. In situ grown bacterial cellulose/MoS2 composites for multi-contaminant wastewater treatment and bacteria inactivation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 277, 118853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Xiong, P.; Liu, J.; Feng, F.; Xun, X.; Gama, F.M.; Zhang, Q.; Yao, F.; Yang, Z.; Luo, H.; et al. Ultrathin, strong, and highly flexible Ti3C2T x MXene/bacterial cellulose composite films for high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 8439–8449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbi, S.; Brugnoli, M.; La China, S.; Montorsi, M.; Gullo, M. Combining microbial cellulose with FeSO4 and FeCl2 by ex situ and in situ methods. Polymers 2025, 17, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Li, J.; Bao, Z.; Hu, M.; Nian, R.; Feng, D.; An, D.; Li, X.; Xian, M. A natural in situ fabrication method of functional bacterial cellulose using a microorganism. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, N.M.; Mattos, A.L.; Silva, L.M.; Brito, E.S.; Rosa, M.F.; Azeredo, H.M. From cashew byproducts to biodegradable active materials: Bacterial cellulose-lignin-cellulose nanocrystal nanocomposite films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susilo, M.H.; Lin, H.W.; Hsieh, C.C.; Huang, Y.C.; Chou, Y.C.; Santoso, S.P.; Lin, S.P.; Cheng, K.C. Sequential cocultivation strategy for producing nisin-enriched foaming bacterial cellulose with enhanced antibacterial and functional properties. Cellulose 2025, 32, 7765–7782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Fan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Li, T.; Qiao, W.; Wu, M.; Ma, T.; Li, G. Production of nisin-containing bacterial cellulose nanomaterials with antimicrobial properties through co-culturing Enterobacter sp. FY-07 and Lactococcus lactis N8. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 251, 117131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Qiao, Y.; Gao, G.; Liao, Z.; Wu, Z.; Saris, P.E.J.; Xu, H.; Qiao, M. A novel co-cultivation strategy to generate low-crystallinity bacterial cellulose and increase nisin yields. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 202, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, W.; Jia, C.; Yang, J.; Gao, G.; Guo, D.; Xu, X.; Wu, Z.; Saris, P.E.J.; Xu, H.; Qiao, M. Production of bacterial cellulose-based peptidopolysaccharide BC-L with anti-listerial properties using a co-cultivation strategy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 274, 133047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarova, N.B.; Liyaskina, E.V.; Revin, V.V. Production of bacterial cellulose by co-cultivation of Komagataeibacter sucrofermentans with producers of dextran Leuconostoc mesenteroides and xanthan Xanthomonas campestris. Biochem. Mosc. Suppl. Ser. B 2023, 17, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugnoli, M.; Mazzini, I.; La China, S.; De Vero, L.; Gullo, M. A microbial co-culturing system for producing cellulose-hyaluronic acid composites. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugnoli, M.; Carvalho, J.P.F.; Arena, M.P.; Oliveira, H.; Vilela, C.; Freire, C.S.R.; Gullo, M. Co-cultivation of Komagataeibacter sp. and Lacticaseibacillus sp. strains to produce bacterial nanocellulose-hyaluronic acid nanocomposite membranes for skin wound healing applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 299, 140208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Płoska, J.; Garbowska, M.; Ścibisz, I.; Stasiak-Różańska, L. Study on obtaining bacterial cellulose by Komagataeibacter xylinus in co-culture with lactic acid bacteria in whey. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 109, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollica, D.; Thanthithum, C.; Lopez, C.C.; Prakitchaiwattana, C. Bioconversion of mangosteen pericarp extract juice with bacterial cellulose production and probiotic integration: A promising approach for functional food supplement development. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Hu, S.; Xu, M.; Hu, Q.; Jiang, S.; Xu, K.; Tremblay, P.-L.; Zhang, T. The facile and controllable synthesis of a bacterial cellulose/polyhydroxybutyrate composite by co-culturing Gluconacetobacter xylinus and Ralstonia eutropha. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 252, 117137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Sun, S.; Sun, J.; Peng, X.; Li, N.; Ullah, M.W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhou, J. Sustainable production of flocculant-containing bacterial cellulose composite for removal of PET nano-plastics. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 469, 143848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, C.; Tang, T.C.; Ott, W.; Dorr, B.A.; Shaw, W.M.; Sun, G.L.; Lu, T.M.; Ellis, T. Living materials with programmable functionalities grown from engineered microbial co-cultures. Nat. Mater. 2021, 20, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senko, O.; Stepanov, N.; Aslanli, A.; Efremenko, E. Bioluminescent ATP-metry in assessing the impact of various microplastic particles on fungal, bacterial, and microalgal cells. Microplastics 2025, 4, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, E.; Kim, H.R. Coloration of bacterial cellulose using in situ and ex situ methods. Text. Res. J. 2019, 89, 1297–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Qi, G.x.; Huang, C.; Yang, X.-Y.; Zhang, H.-R.; Luo, J.; Chen, X.-F.; Xiong, L.; Chen, X.-D. Preparation of Bacterial Cellulose/Inorganic Gel of Bentonite Composite by In Situ Modification. Indian J. Microbiol. 2016, 56, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| BC Producer [Reference] | Added Polysaccharides | Conditions of BC Biosynthesis and Formation of Composites | Characteristics of Obtained Composites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gluconacetobacter sucrofermentans [34] | Alginate 2% (w/v), treated with 5% CaCl2 for 3 h | Glucose (20 g/L) as substrate, static conditions, 28 °C, 5 days | Increase in the tensile strength; Decrease in sample elongation in wet state on the contrary to similar characteristics revealed in a dry state |

| Acetobacter xylinum [35] | Alginate— 0.25–1% (w/v) | Enzymatic hydrolysate of Moso Bamboo as a substrate (20 g/L glucose), static conditions, pH 6.0, 30 °C, 10 days | Increase in pore diameter; Decrease in crystallinity index; Enhancement of the thermal properties and dynamic swelling/de-swelling behavior |

| Gluconacetobacter xylinus [36] | Alginate— 3% (w/w) | Alginate solution was mixed with suspension of cells G. xylinus, then dropped into 0.2 M BaCl2 and placed into the medium with Glucose (20 g/L); 70 rpm, pH 5.5, 26 °C | Increase in water vapor sorption capacity (from 0.07 to 38.9 g/g dry bead); Decrease (19%) in crystallinity |

| Taonella mepensis [37] | Xanthan gum— 0.6% (w/v) | Hydrolysate of residues of Tieguanyin oolong tea (10 g/L of sugars) as a substrate, pH 6.0, static conditions 30 °C, 10 days | Increase in average diameter of the microfibrils, of space between them and water absorption capacity (2.3 times); Decrease in BC crystallinity indexes (2 times) and water release rate |

| Enterobacter sp. [38] | Xanthan gum— 0.1% (w/v) | Glucose (25 g/L) as a substrate, anaerobic fermentation in plastic Petri dishes with different sizes and shapes, static conditions, 30∘C, 1 day | Increase in the fiber diameter, hardness, chewiness, resilience, tensile strength and elongation at break; Decrease in BC crystallinity (27%) and spaces between the cellulose fibers |

| Komagataeibacter hansenii [39] | Pullulan— 0.3–2% (w/v) | Glucose (20 g/L) as a substrate, 30 °C, 200 rpm, 7 days | Increase in the crystallinity (with 0.3–1% of pullulan addition), Young’s modulus and tensile strength (with 1% of pullulan), maximal ribbon width, stress at break and elongation capability; Decrease in the crystallinity with 1.5–2% pullulan. |

| G. xylinus [40] | Chitosan— 5–10 g/L | Dextrose (20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, pH 6.0, 30 °C, 10 days | Appearance of antibacterial properties Decrease in thermal stability and crystallinity |

| A. xylinum [41] | Chitosan— 0.5–4 g/L | Glucose (12.5 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, pH 4.0–5.0, 30 °C, 7 days | Increase in tensile strength; Decrease in swelling properties |

| K. xylinus [42]. | Wheat starch, corn starch, waxy maize starch, high-amylose maize starch or potato starch—1% w/v | Glucose (25 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, 30 °C, 7 days | Increase in springiness, cohesiveness, resilience, porosity and average pore diameter |

| G. xylinus [43] | Pectin— 0.25%(w/v) + 12.5 mM CaCl2 | Glucose (20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, 28 °C, 7 days | Decrease in Young’s modulus (33%), tensile strength (84%), critical strain (75%) and crystallinity |

| Xyloglucan— 0.25% (w/v) | Decrease in Young’s modulus (25%), tensile strength (50%), critical strain (40%) and crystallinity | ||

| Pectin/Xyloglucan—ratio (1:1, 1:2, 1:2.5, 2:1, 2.5:1) | Increase in the Young’s modulus at Pectin/Xyloglucan ratio (2.5:1) by 2 times; Decrease in tensile strength, critical strain and crystallinity in all combinations | ||

| G. xylinus [44] | Xyloglucan (XG), Arabinoxylan (AX), mixed-link glucan— 0.5% (w/v) | Glucose (20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, 30 °C, 3 days | Increase in binding of water, surface area and water holding capacity for BC−XG Decrease in stiffness for BC−MLG composite |

| A. xylinum [32] | Micro-fibrillated cellulose—50 g/L | Mannitol (25 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, pH 5.0, 30 °C, 10 days | Increase in Young′s modulus (per 13%) and tensile strength (per 6%) |

| A. xylinum [32] | Sisal fiber (containing 65%cellulose, 20% hemicellulose, 5% pectine, 10%lygnin) (average length-12 cm)—13.5 g/L | Mannitol (25 g/L) as a substrate; pH 5.0, 30 °C, 105 rpm, 3 days | Increase in interfacial shear strength (per 20%) |

| G. xylinus [45] | Banana peel fibers, containing cellulose and hemicellulose (average length—10 cm)—0.6 g/L | Glucose (6 g/L) as a substrate, 100 rpm, pH 5.0, 30 °C, 3–7 days | Increase in Young’s modulus and tensile strength |

| K. xylinum [46] | Cotton fiber— 6.7 g/L | Mannite (25 g/L) as substrate, static conditions, 30 °C, 6 days | Increase in the elongation at break swelling degree, thermal stability and the UV barrier properties Decrease in the tensile strength |

| G. xylinus [47] | Carboxymethyl cellulose with different substitution degrees (0.7, 0.9 and 1.2)—1% w/v | Glucose (50 g/L) as substrate, static conditions, 28 °C, 3 days | Increase in liquid uptake capacity Decrease in crystallinity, porosity, elastic modulus |

| K. hansenii [48] | Extract from Laminaria japonica with laminarin— 10–40% (v/v) | Glucose (20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, 30 °C, 14 days | Increase in water content, water absorption and Young’s modulus; Decrease in the syneresis, hardness, crystallinity |

| G. xylinus [49] | κ-Carrageenan— 0.3% (w/v) | Glucose (20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, 30 °C, 4–7 days | Increase in hardness and brittleness |

| G. xylinus [50] | Agar 0.1–0.9% w/v with addition of hydroxyapatite—0.025% | Glucose (20 g/L) as substrate, static conditions, 30 °C, 5 days | Increase in pore size Decrease in stress, strain values at break and Young’s modulus values |

| T. mepensis [50] | Low- or high-acyl gellan gum (0.025–0.4% w/v) | Hydrolysate of residues of Chinese medicinal herb as a substrate (sugars—12.5 g/L), pH 7.0, static conditions, 30 °C, 10 days | Increase in hardness, springiness, cohesiveness, chewiness, and resilience; Decrease (per 22%) of the crystallinity index |

| G. hansenii [51] | Exopolysaccharides extracted from Escherichia coli—4–1000 mg/L | Glucose (20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, 30 °C, 5 days | Increase in Young’s modulus and stress at break at 4 mg of EPS/L, Decrease in Young’s modulus and crystallinity and increase in strain at break at 100 mg of EPS/L |

| BC Producer [Reference] | Additives | Conditions of BC Biosynthesis and Formation of Composites | Characteristics of Obtained Composites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymers as additives | |||

| G. xylinus [52] | Collagen—0.4 g/L | Glucose (20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, 30 °C, 14 days | Increase in softness and flexibility; Decrease in the crystallinity degree, moisture content and porosity. |

| A.xylinum [53] | Keratin—3% w/v | Glucose (20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, pH 5.0–6.0, 30 °C, 5 days | Increase in water retention capacity; Decrease in crystallinity and thermal stability |

| Gluconacetobacter kombuchae [54] | Lignin from rice straw—2 g/L | Glucose (20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, 30–35 °C, 21 days | Increase in dense and compact network structure Decrease in water retention capacity, thermal stability and tensile strength, Young’s modulus, and strain-at-break |

| Graphene compounds as additives | |||

| A. xylinum [55] | Graphene oxide—l g/L, graphene suspension/culture medium—1:5, 1:3 and 1:1 (v/v) | Glucose (25 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, 7 days | Increase in pore size, specific surface area, tensile strength and tensile modulus; Decrease in crystallinity |

| K. medellinensis [56] | Graphene oxide— 0.01–0.05 (g/L) | Glucose (20 g/L) as a substrate, 130–150 rpm, 28 °C,5 days | Increase in the thermal stability, swelling capability and drug release |

| Komagataeibacter xylinus [57] | Reduced graphene oxide—1–5% (w/v) | Sugarcane straw hydrolysate (glucose -20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, pH 6.5, 30 °C, 15 days | Increase in the electrical conductivity, Young’s modulus, tensile strength and toughness, Decrease in the crystallinity index |

| K. xylinus [58] | Glucose (20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, pH 6.5, 30 °C, 15 days | Increase in the average pore size, tensile strength, Young’s modulus and conductivity values Decrease in crystallinity | |

| Si- and P-containing additives | |||

| K. xylinus [59] | Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) and Tetramethyl orthosilicate (TMOS)—molar ratio 2:1 for glucose/Si-modification | Glucose modified by TEOS and TMOS (20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, 30 °C, 7 days | Increase in tensile strength of TEOS-modified BC composites Decrease in BC biosynthesis and decrease in average tensile strength of composites formed in presence of TMOS |

| Gluconacetobacter xylinum [60] | Glass nanoparticles, based on SiO2, CaO and P2O5—0.5–7.5 g/L. | Glucose (20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, 30 °C, 7 days | Increase in thermal stability; Decrease in zeta potential; Enhancement of formation of bone-like apatite layers on composite surface; antimicrobial activity (50–100 mg/mL) against clinically important aerobic bacteria and fungi |

| G. xylinus [61] | Hydroxyapatite (200-nm particles)— 10 g/L | Glucose (20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, pH 5.5, 30 °C, 5 days | Increase in average nanofiber diameter; Decrease in the crystallinity |

| Lactiplantibacillus plantarum [62] | Glucose (20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions or 100 rpm, pH 5.5, 30 °C, 5 days | Decrease in the average nanofiber diameter and crystallinity | |

| Biologically active compounds as additives | |||

| K. intermedius, K. maltaceti, and K. Nataicola [63] | Propolis—5–40% (w/v) | Glucose (20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions or agitation at 150 rpm, 30 °C, 7 days | Increase in water-holding capacity and moisture content retention. |

| A. xylinum [64] | Ciprofloxacin—0.2% (w/v) | Glucose (20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, 38 °C, 10 days | Decrease in crystallinity index from 75 to 49% |

| G. xylinus [65] | Hyaluronic acid (1% w/v) and silk sericin (3% w/v) | Glucose (20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, 30 °C, 7 days | Increase in thermal stability, water holding capacity and elongation at break Decrease in crystallinity and tensile strength |

| A. xylinum [66] | AgNO3—0.01–0.1 g/L | Sucrose (50 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, 25 °C, 15 days | Decrease in water absorption, antibacterial properties |

| G. xylinus [67] | Gold nanoparticles—15–35 g/L | Glucose (20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, 26 °C, 7 days | Increase in the specific surface area of average pore volume, total pore volume, average pore area, and total pore area; Decrease in stiffness |

| Additives for photocatalytic, electromagnetic and other properties | |||

| G. xylinus [68] | MoS2—5 mg/mL | Mannitol (25 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, 30 °C, 7 days | Increase in nanofiber network compactness, thermal stability, photocatalytic activity; Decrease in pore size |

| K. xylinus [69] | Ti3C2Tx suspension was mixed with the culture medium in a volume ratio of 1:9, 1:5, 1:2, 1:1, and 4:1 | Glucose (25 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, pH 4.5, 30 °C, 1.5 days | Increase in the tensile strength, Young’s modulus, hydrophilicity and strain at break; Excellent conductivity and electromagnetic interferences shielding properties |

| Komagataeibacter sp. [70] | FeSO4—0.03%/FeCl2—0.02% w/v, FeSO4—0.04%/FeCl2—0.01%, FeSO4—0.05–0.10% w/v. | Glucose (20 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, 28 °C, 4 days | Increase in conductive properties Decrease in elasticity (brittle structure of the BC in the composite) |

| K. sucrofermentans [71] | 6-carboxyfluorescein-glucose (6CF-Glc)— 0.38 or 0.95 g/L | Glucose (25 g/L) as a substrate, static conditions, 30 °C, 5 days | Increase in pore size and elongation at break; Decrease in crystallinity, elastic modulus, tensile strength and thermal stability |

| BC Producer [Reference] | Added Microorganisms to the Artificial Consortium | Conditions of BC Synthesis and Formation of Composites | Composites and Their Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Komagataeibacter xylinum [33] | Lactococcus lactis subsp. Lactis— 1% v/v | MRS medium (de Man, Rogosa, Sharpe), 37 C, 24 h | Composite—BC/Nisin Increase in thermal stability, Young’s modulus, tensile strength, elongation at break Decrease in the BC crystallinity from 84% to 14.6% |

| K. xylinus [73] | L. lactis—inoculum ratios 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, 1:8 (v/v) | MRS medium, static conditions, 37 C, 18 h | Composite—BC/Nisin Increase in BC porosity; Decrease in the fiber sizes by 1.2 times |

| Enterobacter sp. [74] | L. lactis— 1% v/v | Glucose (25 g/L) as substrate, static conditions, 30 °C, 1 day | Composite—BC/Nisin Decrease in crystallinity |

| Enterobacter sp. [75] | L. lactis—inoculum ratios to 1:2, 1:1, 2:1, 4:1, 8:1 | Glucose (25 g/L) as substrate, static conditions, 30 °C, 1 day | Composite—BC/Nisin Increase of thermal stability; Decrease in crystallinity up to 29% |

| Kosakonia oryzendophytica [76] | Leuconostoc carnosum— 1% v/v (107 CFU/mL) | Sucrose (10 g/L) and glucose (15 g/L) as substrates, 30 °C, 1.5 days | Composite—BC/Leukocin Decrease in the crystallinity per 4% |

| K. sucrofermentans [77] | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | Molasses (50 g/L), pH 5.0, 28 °C, 250 rpm, 3 days or static conditions for 5 days | Composite—BC/Dextran Decrease in crystallinity degree up to 2 times |

| K. hansenii [39] | Aureobasidium pullulans—4 × 106 CFU/mL | Glucose (50 g/L) as a substrate, 30 °C, 200 rpm, 7 days | Composite—BC/Pullulan Increase in the maximum ribbon width, Young’s modulus |

| K. xylinus or Komagataeibacter sp. [78] | Lactobacillus rhamnosus or L. casei (106 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL) | Glucose (30 g/L) as substrate, 30 °C, static condition, 3 days | Composite—BC/Guluronic acid Increase in average fiber diameter; Decrease in crystallinity index (per 2–8%), water uptake capacity |

| Komagataeibacter sp. [79] | Lactobacillus casei— 106 CFU/mL | Glucose (30 g/L) as substrate, static conditions, 30 °C, 3 days | Composite—BC/Guluronic acid Increase in the crystallinity (12%), Young’s modulus (3.5 times), tensile stress at break (14.5 times), water absorption capacity (58%) |

| K. xylinus [80] | Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. delbrueckii or L. helveticus —5% v/v | Whey (70 g/L) as substrate, pH 4.8, static conditions, 30 °C, 14 days | Composite—BC/Exopolysaccharides Increase in the Young’s modulus, strain at break, stress at break, thermal stability |

| K. xylinus [81] | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum— 107 CFU/mL (inoculum ratio 1:1) | Mangosteen pericarp extract juice (20% v/v) as a substrate, static conditions, 30 °C, 14 days | Composite—BC/Exopolysaccharides Increase in cohesiveness; Decrease in the hardness, gumminess, chewiness and springiness |

| Gluconacetobacter xylinus [82] | Ralstonia eutropha 0.5–2% (v/v) | Glucose (50 g/L) as a substrate, 30 °C, 200 rpm, 1 day | Composite—BC/Polyhydroxybutyrates Increase in the tensile strength and Young’s modulus by 3 times; Decrease in elongation at break |

| Taonella mepensis [83] | Diaphorobacter nitroreducens— 50 mL/L (1.0 × 107 CFU/mL) | Hydrolysate of polyethylene terephthalate ammonia with addition of 10 g/L glucose, static conditions, pH 7.0, 30 °C, 7 days | Composite—BC/Bacterial flocculants Increase in the pore volume, crystallinity, surface area, tensile strength and Young’s modulus |

| Komagataeibacter haeticus [84] | Genetically modified S. cerevisiae cells— inoculum ratio 1:100 | Glucose (20 g/L) as substrate, 30 °C, 4 days | Composite—BC/Enzymes Decrease in the tensile strength at break, Young’s modulus, stiffness, viscoelastic properties |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Efremenko, E.; Stepanov, N.; Aslanli, A.; Maslova, O.; Chumachenko, I.; Senko, O.; Bhattacharya, A. Changed Characteristics of Bacterial Cellulose Due to Its In Situ Biosynthesis as a Part of Composite Materials. Polysaccharides 2025, 6, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040114

Efremenko E, Stepanov N, Aslanli A, Maslova O, Chumachenko I, Senko O, Bhattacharya A. Changed Characteristics of Bacterial Cellulose Due to Its In Situ Biosynthesis as a Part of Composite Materials. Polysaccharides. 2025; 6(4):114. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040114

Chicago/Turabian StyleEfremenko, Elena, Nikolay Stepanov, Aysel Aslanli, Olga Maslova, Ivan Chumachenko, Olga Senko, and Amrik Bhattacharya. 2025. "Changed Characteristics of Bacterial Cellulose Due to Its In Situ Biosynthesis as a Part of Composite Materials" Polysaccharides 6, no. 4: 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040114

APA StyleEfremenko, E., Stepanov, N., Aslanli, A., Maslova, O., Chumachenko, I., Senko, O., & Bhattacharya, A. (2025). Changed Characteristics of Bacterial Cellulose Due to Its In Situ Biosynthesis as a Part of Composite Materials. Polysaccharides, 6(4), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040114