Effect of Glycerol and Isosorbide on Mechanical, Thermal, and Physicochemical Properties During Retrogradation of a Cassava Thermoplastic Starch

Abstract

1. Introduction

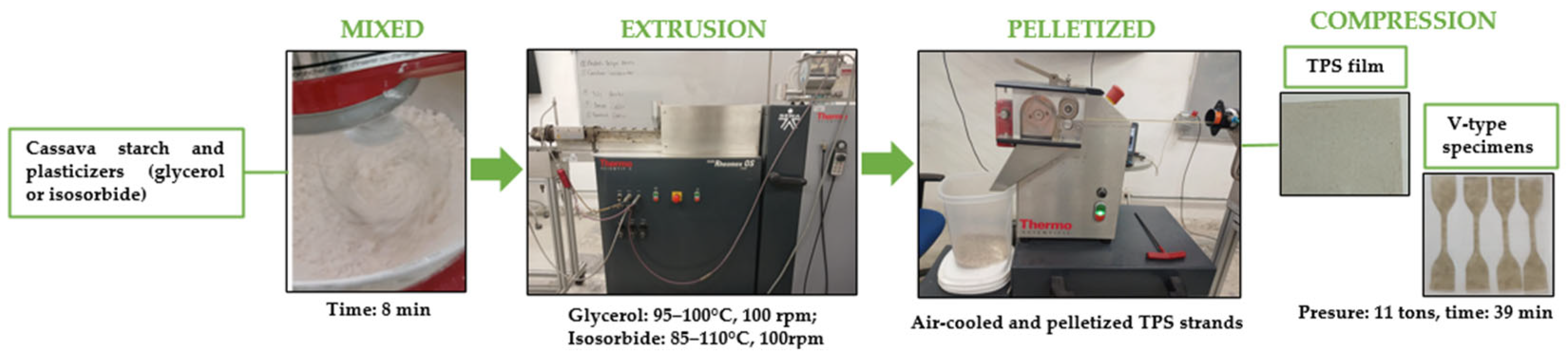

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Obtaining Thermoplastic Cassava Starch

2.3. Characterization Techniques

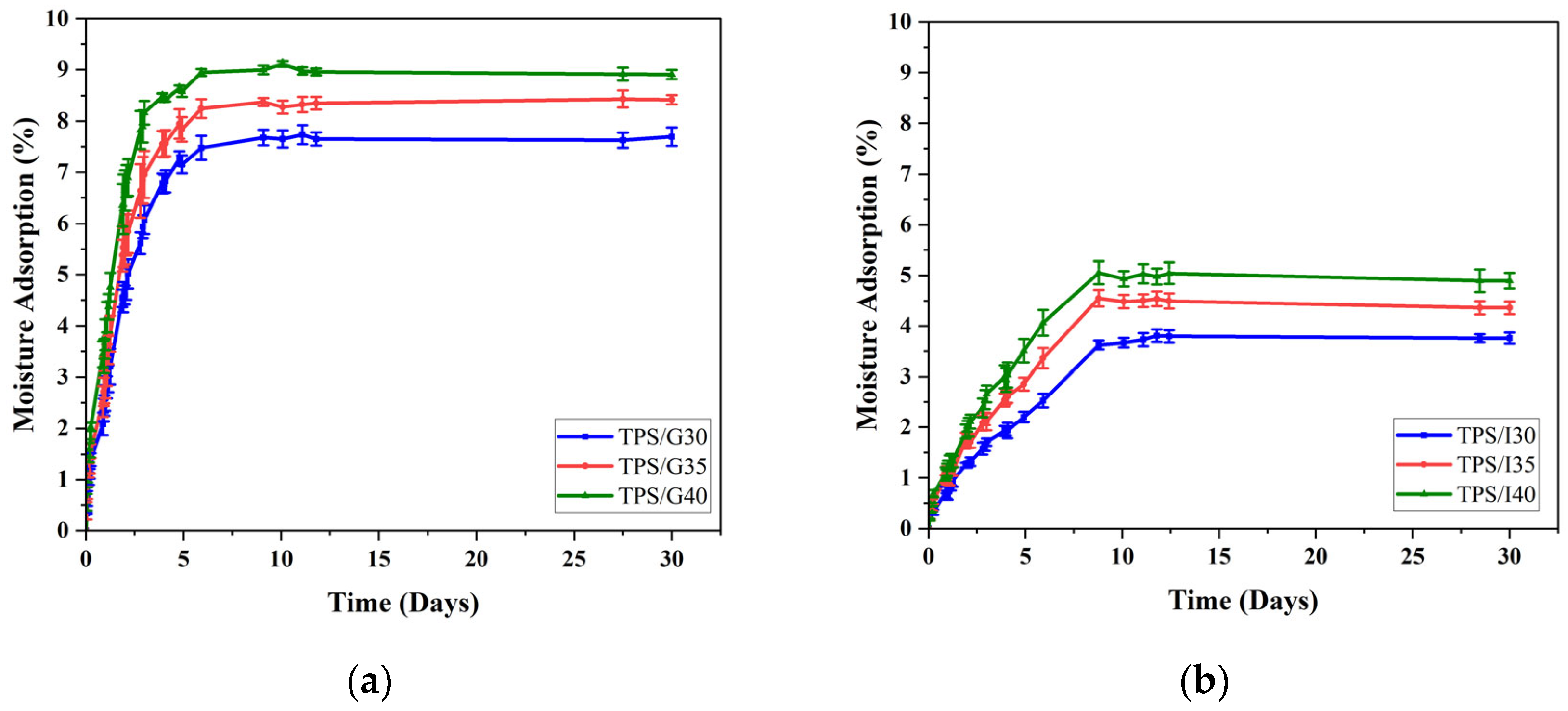

2.3.1. Moisture Absorption

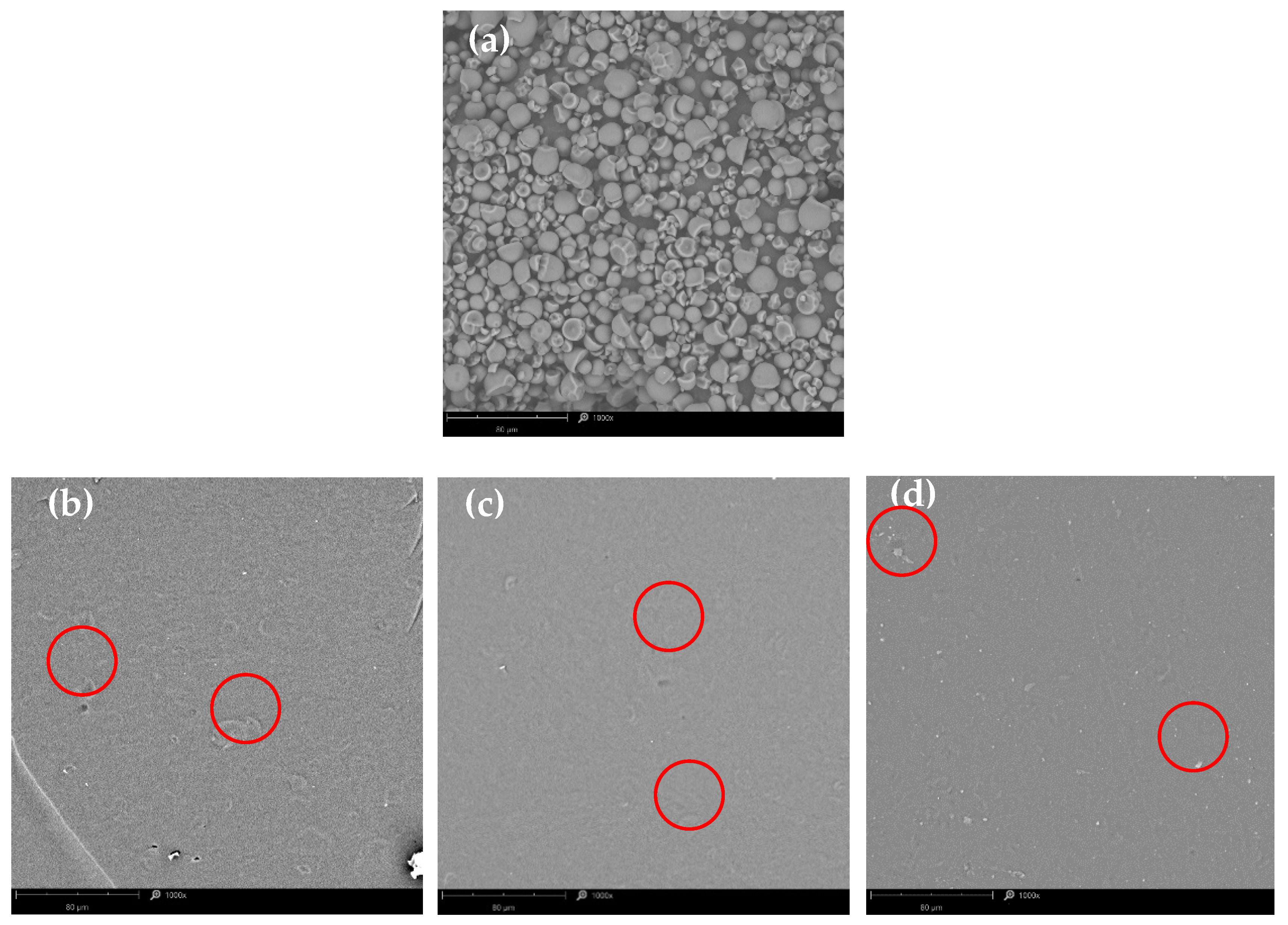

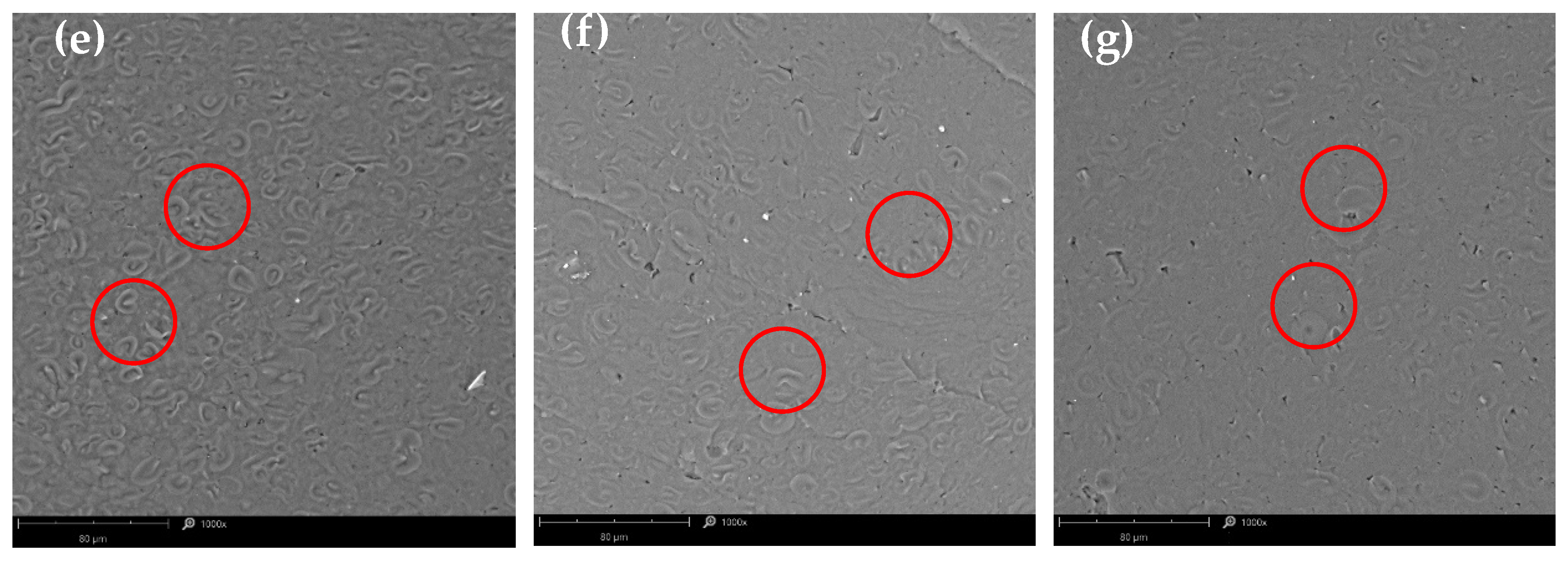

2.3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

2.3.4. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.3.5. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2.3.6. Mechanical Properties

2.3.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Moisture Absorption

3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

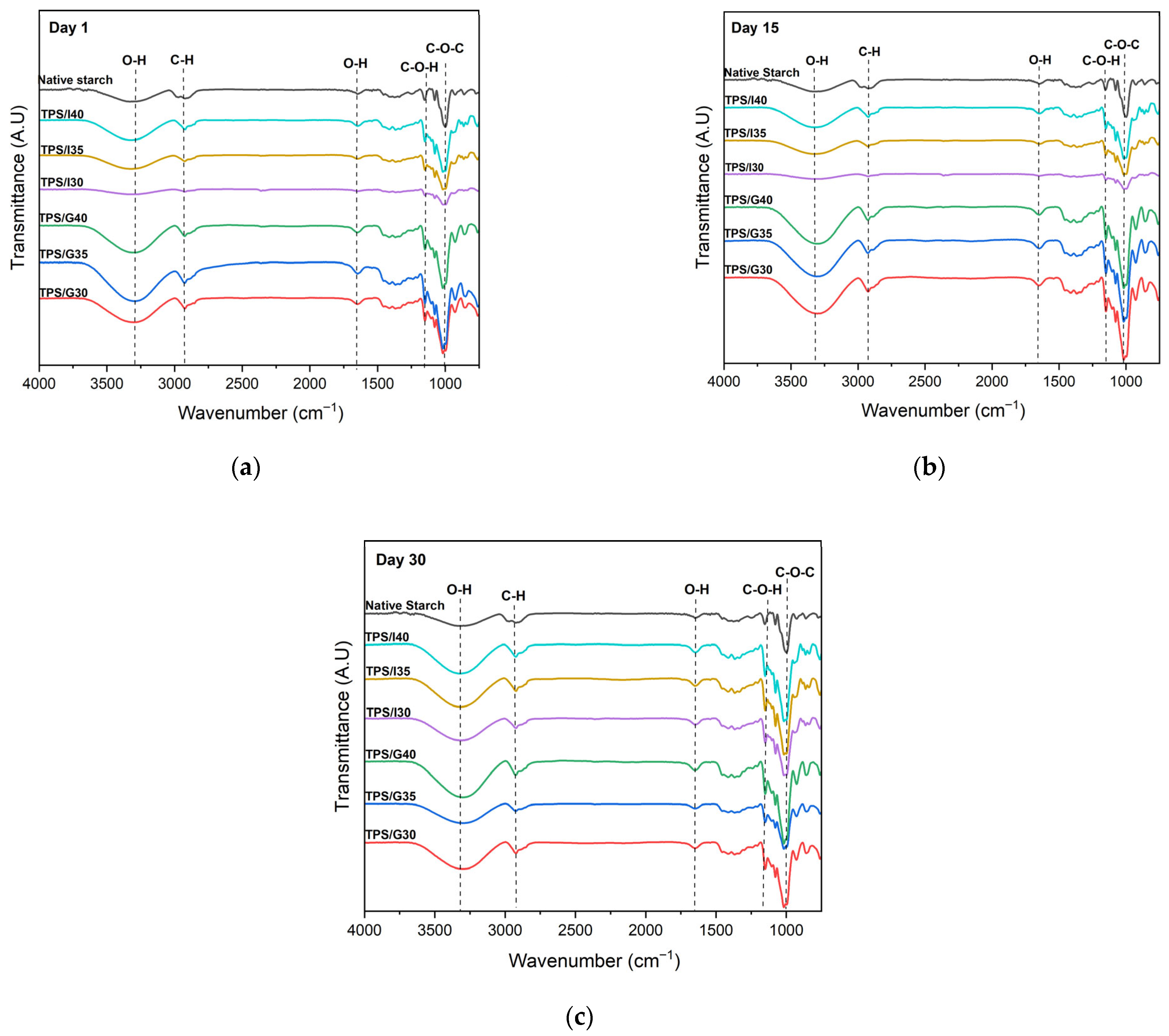

3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

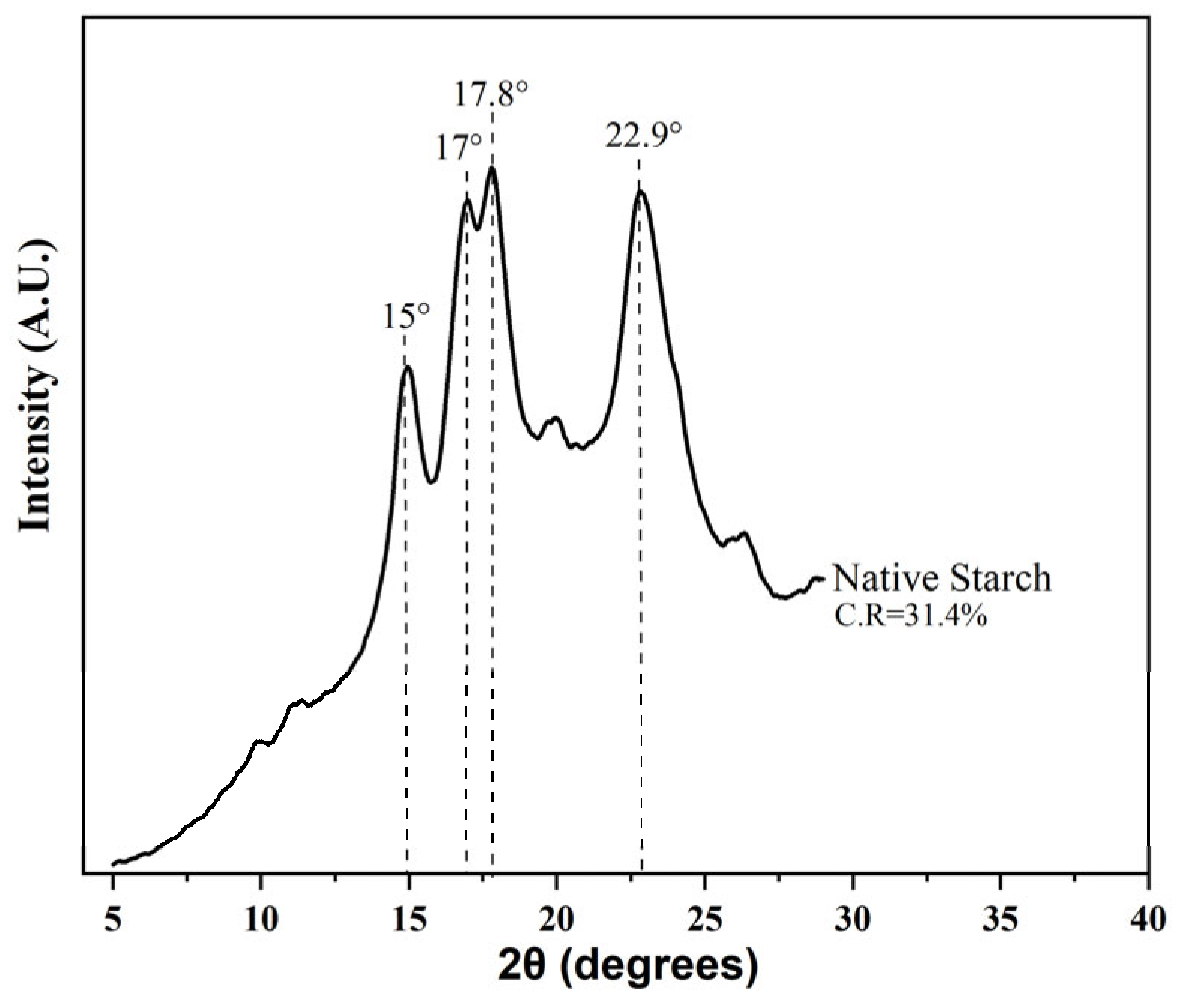

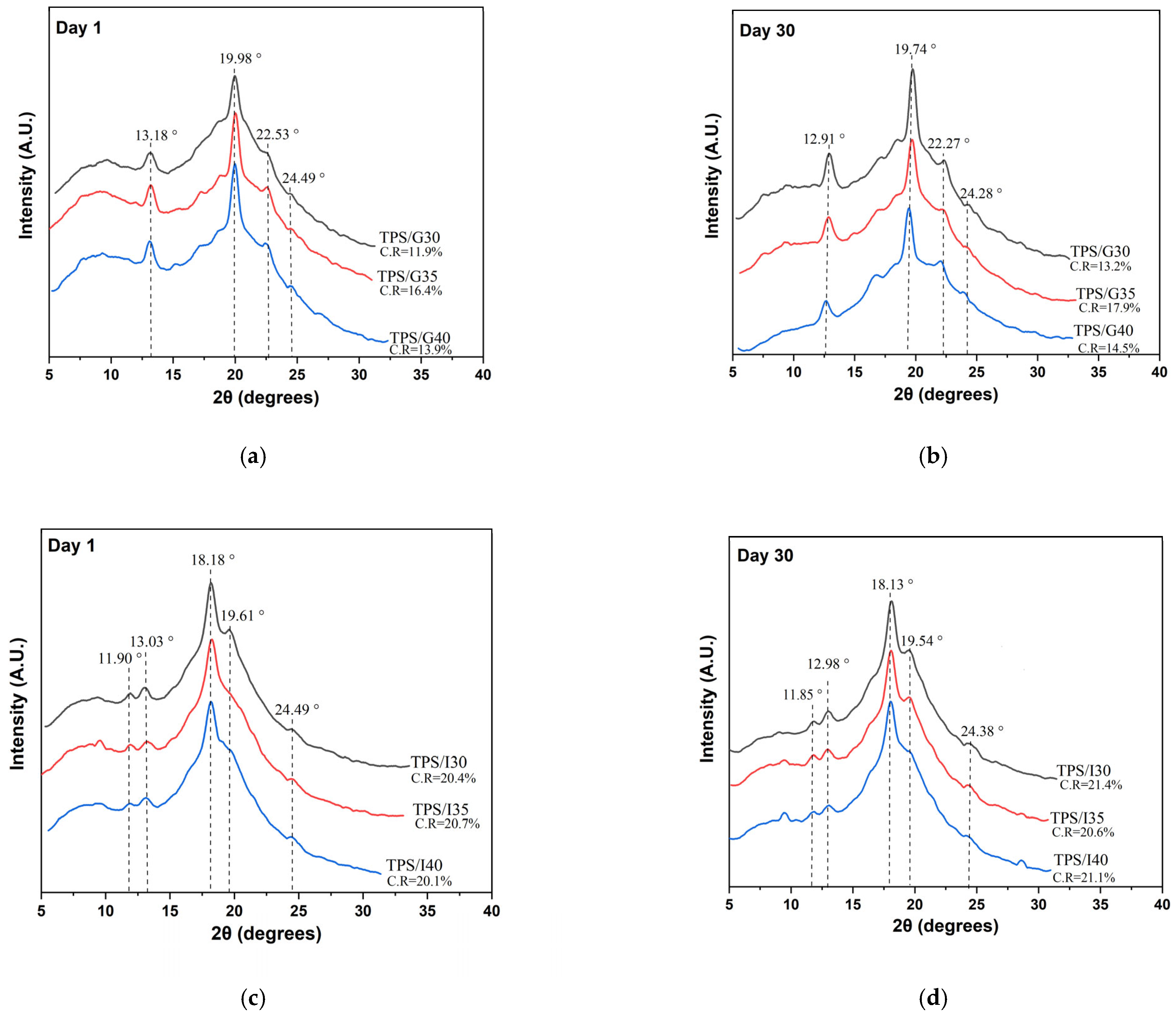

3.4. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

3.5. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

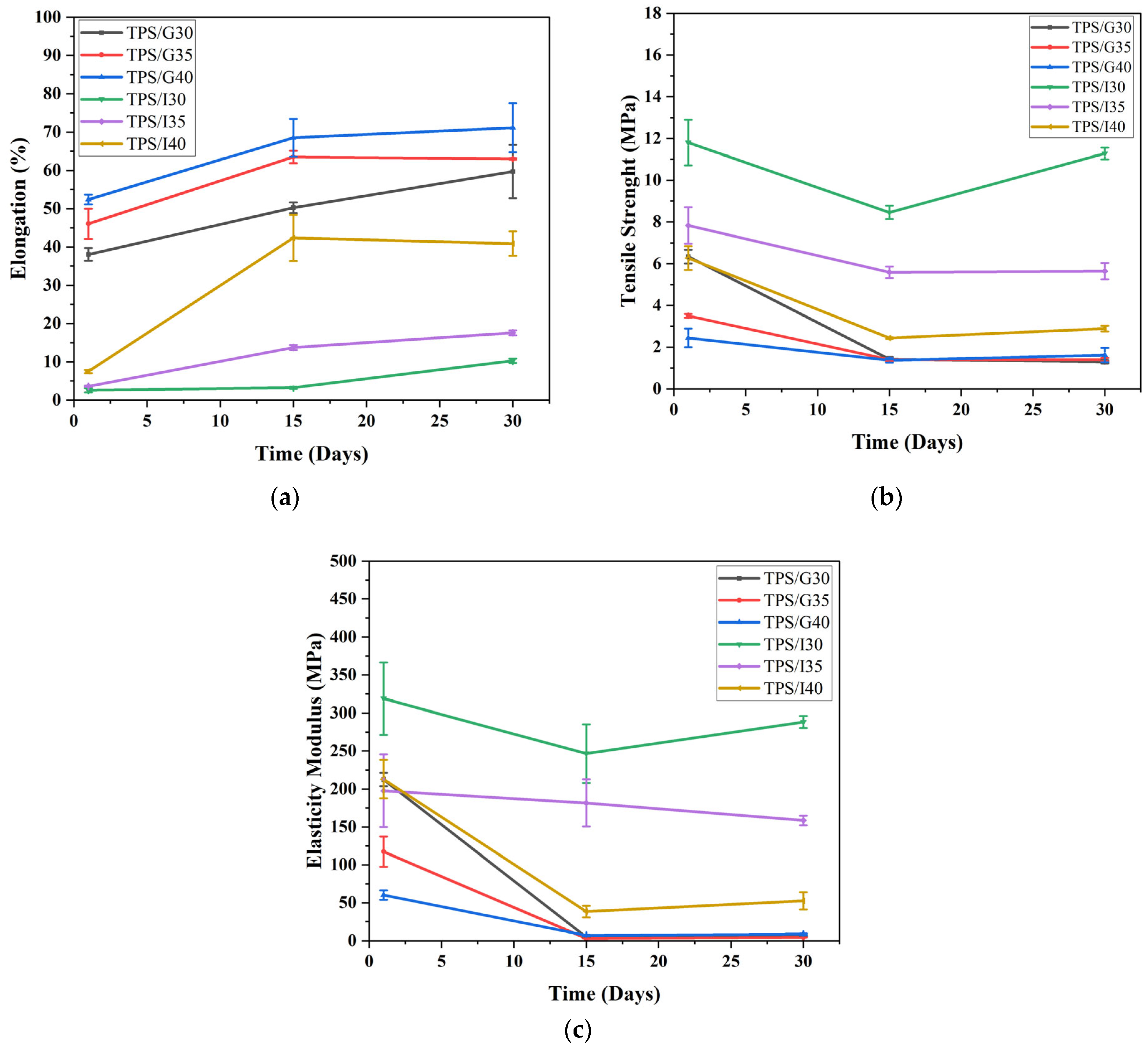

3.6. Mechanical Tensile Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, C.; Show, P.L.; Ho, S.H. Progress and perspective on algal plastics—A critical review. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 289, 121700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jantasrirad, S.; Mayakun, J.; Numnuam, A.; Kaewtatip, K. Effect of filler and sonication time on the performance of brown alga (Sargassum plagiophyllum) filled cassava starch biocomposites. Algal Res. 2021, 56, 102321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tappiban, P.; Smith, D.R.; Triwitayakorn, K.; Bao, J. Recent understanding of starch biosynthesis in cassava for quality improvement: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 83, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, B.; Bilal Khan Niazi, M.; Samin, G.; Jahan, Z. Thermoplastic starch: A possible biodegradable food packaging material—A review. J. Food Process Eng. 2017, 40, e12447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Pollet, E.; Halley, P.J.; Avérous, L. Starch-based nano-biocomposites. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2013, 38, 1590–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, M.; Pircheraghi, G.; Bagheri, R. Optimizing the mechanical and physical properties of thermoplastic starch via tuning the molecular microstructure through co-plasticization by sorbitol and glycerol. Polym. Int. 2017, 66, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, H.; Guidez, A.; Prashantha, K.; Soulestin, J.; Lacrampe, M.F.; Krawczak, P. Studies on the effect of storage time and plasticizers on the structural variations in thermoplastic starch. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 115, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chantawee, K.; Riyajan, S.A. Carboxylated styrene-butadiene rubber adhesion for biopolymer product-based from cassava starch and sugarcane leaves fiber. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 125, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montilla-Buitrago, C.E.; Gómez-López, R.A.; Solanilla-Duque, J.F.; Serna-Cock, L.; Villada-Castillo, H.S. Effect of plasticizers on properties, retrogradation, and processing of extrusion-obtained thermoplastic starch: A review. Starch-Stärke 2021, 73, 2100060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, K.; Iturriaga, L.; González, A.; Eceiza, A.; Gabilondo, N. Improving mechanical and barrier properties of thermoplastic starch and polysaccharide nanocrystals nanocomposites. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 123, 109415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Area, M.R.; Montero, B.; Rico, M.; Barral, L.; Bouza, R.; López, J. Isosorbide plasticized corn starch filled with poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) microparticles: Properties and behavior under environmental factors. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 202, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mina Hernández, J.H. Effect of the incorporation of polycaprolactone (PCL) on the retrogradation of binary blends with cassava thermoplastic starch (TPS). Polymers 2020, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Area, M.R.; Montero, B.; Rico, M.; Barral, L.; Bouza, R.; López, J. Properties and behavior under environmental factors of isosorbide plasticized starch reinforced with microcrystalline cellulose biocomposites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 2028–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigham, C. Biopolymers: Biodegradable alternatives to traditional plastics. In Green Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 753–770. [Google Scholar]

- Battegazzore, D.; Bocchini, S.; Nicola, G.; Martini, E.; Frache, A. Isosorbide, a green plasticizer for thermoplastic starch that does not retrogradate. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 119, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Area, M.R.; Rico, M.; Montero, B.; Barral, L.; Bouza, R.; López, J.; Ramírez, C. Corn starch plasticized with isosorbide and filled with microcrystalline cellulose: Processing and characterization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 206, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, K.; Martin, L.; González, A.; Retegi, A.; Eceiza, A.; Gabilondo, N. D-isosorbide and 1, 3-propanediol as plasticizers for starch-based films: Characterization and aging study. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-López, R.A.; Montilla-Buitrago, C.E.; Villada-Castillo, H.S.; Sáenz-Galindo, A.; Avalos-Belmontes, F.; Serna-Cock, L. Co-Plasticization of Starch with Glycerol and Isosorbide: Effect on Retrogradation in Thermo-Plastic Cassava Starch Films. Polymers 2023, 15, 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arfiathi, A.; Sumirat, R.; Syamani, F.A.; Lubis, M.A.R.; Filianty, F.; Nurhamiyah, Y. Effect of citric acid on the properties of thermoplastic bitter cassava starch plasticized with isosorbide. Polym. Renew. Resour. 2024, 15, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Gu, Z.; Cheng, L.; Hong, Y.; Li, Z. Pasting and thermal properties of waxy corn starch modified by1, 4—glucan branching enzyme. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 97, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.; Conway, H.F.; Pheiser, V.F.; Griffin, E.L. Gelatinization of corn grits by roll and extrusion cooking. Cereal Sci. Today 1969, 14, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, E.D.M.; Curvelo, A.A.; Corrêa, A.C.; Marconcini, J.M.; Glenn, G.M.; Mattoso, L.H. Properties of thermoplastic starch from cassava bagasse and cassava starch and their blends with poly (lactic acid). Ind. Crops Prod. 2012, 37, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, M.; Valadez-González, A.; Herrera-Franco, P.; Zuluaga, F.; Delvasto, S. Physicochemical Characterization of Natural and Acetylated Thermoplastic Cassava Starch. DYNA 2011, 78, 166–173. [Google Scholar]

- Toro, F.; Jose, M.; Bolaños, C.A. Estudio físico-mecánico y térmico de una resina natural Mopa-Mopa acondicionada a diferentes humedades relativas. Biotecnol. Sect. Agropecu. Agroind. 2013, 11, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Florencia, V.; López, O.V.; García, M.A. Exploitation of by-products from cassava and ahipa starch extraction as filler of thermoplastic corn starch. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 182, 107653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, M.; Valadez, A.; Toledano, T. Estudio Fisicoquímico de mezclas de almidón termoplástico (TPS) y policaprolactona (PCL). Biotecnol. Sect. Agropecu. Agroind. 2013, 11, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nara, S.; Komiya, T.J.S. Studies on the relationship between water-satured state and crystallinity by the diffraction method for moistened potato starch. Starch-Stärke 1983, 35, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travalini, A.P.; Lamsal, B.; Magalhães, W.L.E.; Demiate, I.M. Cassava starch films reinforced with lignocellulose nanofibers from cassava bagasse. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 139, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galera Manzano, L.M.; Ruz Cruz, M.Á.; Moo Tun, N.M.; Valadez González, A.; Jose, M.H. Effect of cellulose and cellulose nanocrystal contents on the biodegradation, under composting conditions, of hierarchical PLA biocomposites. Polymers 2021, 13, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumaidin, R.; Diah, N.A.; Ilyas, R.A.; Alamjuri, R.H.; Yusof, F.A.M. Processing and characterisation of banana leaf fibre reinforced thermoplastic cassava starch composites. Polymers 2021, 13, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, E.D.M.; Pasquini, D.; Curvelo, A.A.; Corradini, E.; Belgacem, M.N.; Dufresne, A. Cassava bagasse cellulose nanofibrils reinforced thermoplastic cassava starch. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 78, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edhirej, A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Jawaid, M.; Zahari, N.I. Effect of various plasticizers and concentration on the physical, thermal, mechanical, and structural properties of cassava-starch-based films. Starch-Stärke 2017, 69, 1500366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatmiko, T.H.; Poeloengasih, C.D.; Prasetyo, D.J.; Rosyida, V.T. Effect of plasticizer on moisture sorption isotherm of sugar palm (Arenga Pinnata) starch film. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, International Symposium on Frontier of Applied Physics (ISFAP) 2015, Bandung, Indonesia, 5–7 October 2015; AIP Publishing: Melville, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 1711, p. 080004. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, J.; Salas, J. Morphological Characterization of Native Starch Granule: Appearance, Shape, Size and its Distribution. Rev. Ing. 2008, 27, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akonor, P.T.; Osei Tutu, C.; Arthur, W.; Adjebeng-Danquah, J.; Affrifah, N.S.; Budu, A.S.; Saalia, F.K. Granular structure, physicochemical and rheological characteristics of starch from yellow cassava (Manihot esculenta) genotypes. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoft, E. Understanding Starch Structure: Recent Progress. Agronomy 2017, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargarzadeh, H.; Johar, N.; Ahmad, I. Starch biocomposite film reinforced by multiscale rice husk fiber. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2017, 151, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinaldo, J.S.; Milfont, C.H.; Gomes, F.P.; Mattos, A.L.; Medeiros, F.G.; Lopes, P.F.; Ito, E.N. Influence of grape and acerola residues on the antioxidant, physicochemical and mechanical properties of cassava starch biocomposites. Polym. Test. 2021, 93, 107015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, V.C.R.; Blanco-Pascual, N.; Tribuzi, G.; Laurindo, J.B. Effect of the degree of acetylation, plasticizer concentration and relative humidity on cassava starch films properties. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 39, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edhirej, A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Jawaid, M.; Zahari, N.I. Cassava/sugar palm fiber reinforced cassava starch hybrid composites: Physical, thermal and structural properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 101, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagnelli, D.; Hebelstrup, K.H.; Leroy, E.; Rolland-Sabaté, A.; Guilois, S.; Kirkensgaard, J.J.; Blennow, A. Plant-crafted starches for bioplastics production. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 152, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Tian, X.; Jin, R.; Li, D. Preparation and characterization of nanocomposite films containing starch and cellulose nanofibers. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 123, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Niño, J.P.; Mina-Hernandez, J.H.; Solanilla-Duque, J.F. Effect of cellulose nanofibers and plantain peel fibers on mechanical, thermal, physicochemical properties in bio-based composites storage time. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, M.; Valadez, A.; Herrera, P.; Toleda, T. Influencia del tiempo de almacenamiento en las propiedades estructurales de un almidón termoplástico de yuca (TPS). Ing. Compet. 2009, 11, 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Fan, L.; Pang, J.; Tan, D. Effect of tensile action on retrogradation of thermoplastic cassava starch/nanosilica composite. Iran. Polym. J. 2020, 29, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.S.; Osman, A.F.; Adnan, S.A.; Ibrahim, I.; Ahmad Salimi, M.N.; Alrashdi, A.A. Effective aging inhibition of the thermoplastic corn starch films through the use of green hybrid filler. Polymers 2022, 14, 2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa-Flórez, J.; Cadena-Chamorro, E.; Salcedo-Mendoza, J.; Rodríguez-Sandoval, E.; Ciro-Velásquez, H.; Serna-Fadul, T. Enzymatic biocatalysis processes on the semicrystalline and morphological order of native cassava starches (Manihot esculenta). Rev. Fac. Nac. Agron. Medellín 2024, 77, 10839–10852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, K.P.C.; Mendes, J.F.; Ferreira, L.F.; Martins, M.A.; Mendoza, J.S.; Mendes, R.F. Hydrophobic bio-composites of stearic acid starch esters and micro fibrillated cellulose processed by extrusion. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 221, 119313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, B.M.J.; Gerrits, W.J.J.; Bruininx, E.M.A.M.; Schols, H.A. Amylopectin structure and crystallinity explains variation in digestion kinetics of starches across botanic sources in an in vitro pig model. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F. Composition, structure, physicochemical properties, and modifications of cassava starch. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 122, 456–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, A.; Tabarsa, T.; Ashori, A.; Shakeri, A.; Mashkour, M. Thermoplastic starch foamed composites reinforced with cellulose nanofibers: Thermal and mechanical properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 197, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaf, R.A.; Karman, A.P.; Janssen, L.P. Material properties and glass transition temperatures of different thermoplastic starches after extrusion processing. Starch-Stärke 2003, 55, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, L.; Stoclet, G.; Lefebvre, J.M.; Gaucher, V. Mechanical behavior of thermoplastic starch: Rationale for the temperature-relative humidity equivalence. Polymers 2022, 14, 2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, T.J.; Suniaga, J.; Monsalve, A.; García, N.L. Influence of beet flour on the relationship surface-properties of edible and intelligent films made from native and modified plantain flour. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 54, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, R.; Ortega-Toro, R.; Tesser, R.; Mallardo, S.; Collazo-Bigliardi, S.; Chiralt Boix, A.; Santagata, G. Poly (lactic acid)/thermoplastic starch films: Effect of cardoon seed epoxidized oil on their chemicophysical, mechanical, and barrier properties. Coatings 2019, 9, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanvrier, H.; Uthayakumaran, S.; Appelqvist, I.A.; Gidley, M.J.; Gilbert, E.P.; López-Rubio, A. Influence of storage conditions on the structure, thermal behavior, and formation of enzyme-resistant starch in extruded starches. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 9883–9890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, C.M.O.; Castillo, E.A.; Flores, S.; Gerschenson, L.N.; Bengoechea, C. Effect of plasticizer composition on the properties of injection molded cassava starch-based bioplastics. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2023, 40, 101218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, M.; Rodríguez-Llamazares, S.; Barral, L.; Bouza, R.; Montero, B. Processing and characterization of polyols plasticized-starch reinforced with microcrystalline cellulose. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 149, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Code | Type of Plasticizer | Plasticizer Content (%) |

|---|---|---|

| TPS/G30 | Glycerol | 30 |

| TPS/G35 | Glycerol | 35 |

| TPS/G40 | Glycerol | 40 |

| TPS/I30 | Isosorbide | 30 |

| TPS/I35 | Isosorbide | 35 |

| TPS/I40 | Isosorbide | 40 |

| Vibrational Assignment | Wavenumber (cm−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native Starch | TPS | |||

| Stretching vibration of the hydroxyl bond (-OH) | 3354 | 3300 | ||

| Asymmetric stretching vibration (C–H) | 2972 | 2922 | 2922 | |

| Bending vibration O–H of absorbed water | 1650 | 1650 | ||

| C–O stretching vibration (C–O–H bond) | 1152 | 1078 | 1150 | 1077 |

| C–O stretching vibration (C–O–C bond) | 999 | 1016 | 998 | |

| Sample | Day 1 | Day 30 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tg (°C) | Tm (°C) | ΔHm (J.g−1) | Tg (°C) | Tm (°C) | ΔHm (J.g−1) | |

| TPS/G30 | 36.9 | 173.2 | 2.9 | 92.8 | 154.5 | 27.6 |

| TPS/G35 | 37.4 | 178.0 | 2.9 | 69.6 | 166.7 | 10.8 |

| TPS/G40 | 34.9 | 193.6 | 1.0 | 68.8 | 90.4 | 7.5 |

| TPS/I30 | 37.1 | 154.6 | 2.0 | 69.8 | 136.8 | 18.2 |

| TPS/I35 | 37.4 | 155.7 | 1.9 | 69.9 | 146.4 | 10.6 |

| TPS/I40 | 36.5 | 158.1 | 8.3 | 69.3 | 141.3 | 32.3 |

| Mechanical Properties | Sample | Day 1 | Day 15 | Day 30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elongation (%) | TPS/G30 | 38.1 ± 1.7 (Aa) | 50.2 ± 1.0 (Aa) | 59.7 ± 8.0 (Aa) |

| TPS/G35 | 46.1 ± 4.0 (Ab) | 63.5 ± 1.7 (Ab) | 63.0 ± 0.2 (Ab) | |

| TPS/G40 | 52.4 ± 2.1 (Ac) | 68.5 ± 3.6 (Ac) | 71.2 ± 8.7 (Ac) | |

| TPS/I30 | 2.6 ± 0.6 (Ba) | 3.3 ± 0.3 (Ba) | 10.3 ± 0.4 (Ba) | |

| TPS/I35 | 3.6 ± 0.1 (Bb) | 13.8 ± 0.7 (Bb) | 17.6 ± 0.7 (Bb) | |

| TPS/I40 | 7.5 ± 0.3 (Bc) | 42.4 ± 5.7 (Bc) | 40.9 ± 3.1 (Bc) | |

| Elasticity Modulus (Mpa) | TPS/G30 | 212.5 ± 8.6 (Aa) | 4.9 ± 0.2 (Aa) | 6.1 ± 0.5 (Aa) |

| TPS/G35 | 117.5 ± 19.8 (Ab) | 3.2 ± 0.2 (Ab) | 4.4 ± 0.3 (Ab) | |

| TPS/G40 | 60.1 ± 6.2 (Ac) | 7.3 ± 0.7 (Ac) | 8.7 ± 0.7 (Ac) | |

| TPS/I30 | 318.9 ± 47.6 (Ba) | 246.8 ± 38.5 (Ba) | 288.3 ± 8.0 (Ba) | |

| TPS/I35 | 197.7 ± 77.7 (Bb) | 181.7 ± 22.1 (Bb) | 158.6 ± 6.4 (Bb) | |

| TPS/I40 | 213.1 ± 25.3 (Bc) | 38.4 ± 7.6 (Bc) | 52.5 ± 11.3 (Bc) | |

| Tensile (Mpa) | TPS/G30 | 6.3 ± 0.3 (Aa) | 1.4 ± 0.1 (Aa) | 1.3 ± 0.1 (Aa) |

| TPS/G35 | 3.5 ± 0.1 (Ab) | 1.4 ± 0.1 (Ab) | 1.4 ± 0.1 (Ab) | |

| TPS/G40 | 2.5 ± 0.4 (Ac) | 1.4 ± 0.0 (Ac) | 1.6 ± 0.1 (Ac) | |

| TPS/I30 | 11.8 ± 1.1 (Ba) | 10.7 ± 1.8 (Ba) | 11.0 ± 1.3 (Ba) | |

| TPS/I35 | 7.8 ± 0.9 (Bb) | 5.5 ± 0.1 (Bb) | 5.6 ± 0.2 (Bb) | |

| TPS/I40 | 6.3 ± 0.6 (Bc) | 2.4 ± 0.0 (Bc) | 2.9 ± 0.1 (Bc) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Acosta-Tirado, A.C.; Salcedo-Mendoza, J.; Martinez-Mera, N.; Ramírez-Malule, H.; Mina Hernández, J.H. Effect of Glycerol and Isosorbide on Mechanical, Thermal, and Physicochemical Properties During Retrogradation of a Cassava Thermoplastic Starch. Polysaccharides 2025, 6, 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040112

Acosta-Tirado AC, Salcedo-Mendoza J, Martinez-Mera N, Ramírez-Malule H, Mina Hernández JH. Effect of Glycerol and Isosorbide on Mechanical, Thermal, and Physicochemical Properties During Retrogradation of a Cassava Thermoplastic Starch. Polysaccharides. 2025; 6(4):112. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040112

Chicago/Turabian StyleAcosta-Tirado, Andrea Carolina, Jairo Salcedo-Mendoza, Nicolas Martinez-Mera, Howard Ramírez-Malule, and José Herminsul Mina Hernández. 2025. "Effect of Glycerol and Isosorbide on Mechanical, Thermal, and Physicochemical Properties During Retrogradation of a Cassava Thermoplastic Starch" Polysaccharides 6, no. 4: 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040112

APA StyleAcosta-Tirado, A. C., Salcedo-Mendoza, J., Martinez-Mera, N., Ramírez-Malule, H., & Mina Hernández, J. H. (2025). Effect of Glycerol and Isosorbide on Mechanical, Thermal, and Physicochemical Properties During Retrogradation of a Cassava Thermoplastic Starch. Polysaccharides, 6(4), 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040112