Cross-Sectional Analysis of Food Group Consumption and Obesity in Children Aged 6–23 Months with Normal and Stunted Growth Patterns in Pakistan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design and Study Setting

2.2. Study Participants, Sample Size, and Sampling Techniques

2.3. Study Variables

2.3.1. Exposure Variables

2.3.2. Outcome Variables

2.3.3. Study Covariates

2.4. Data Access and Cleaning Methods

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Study Sample

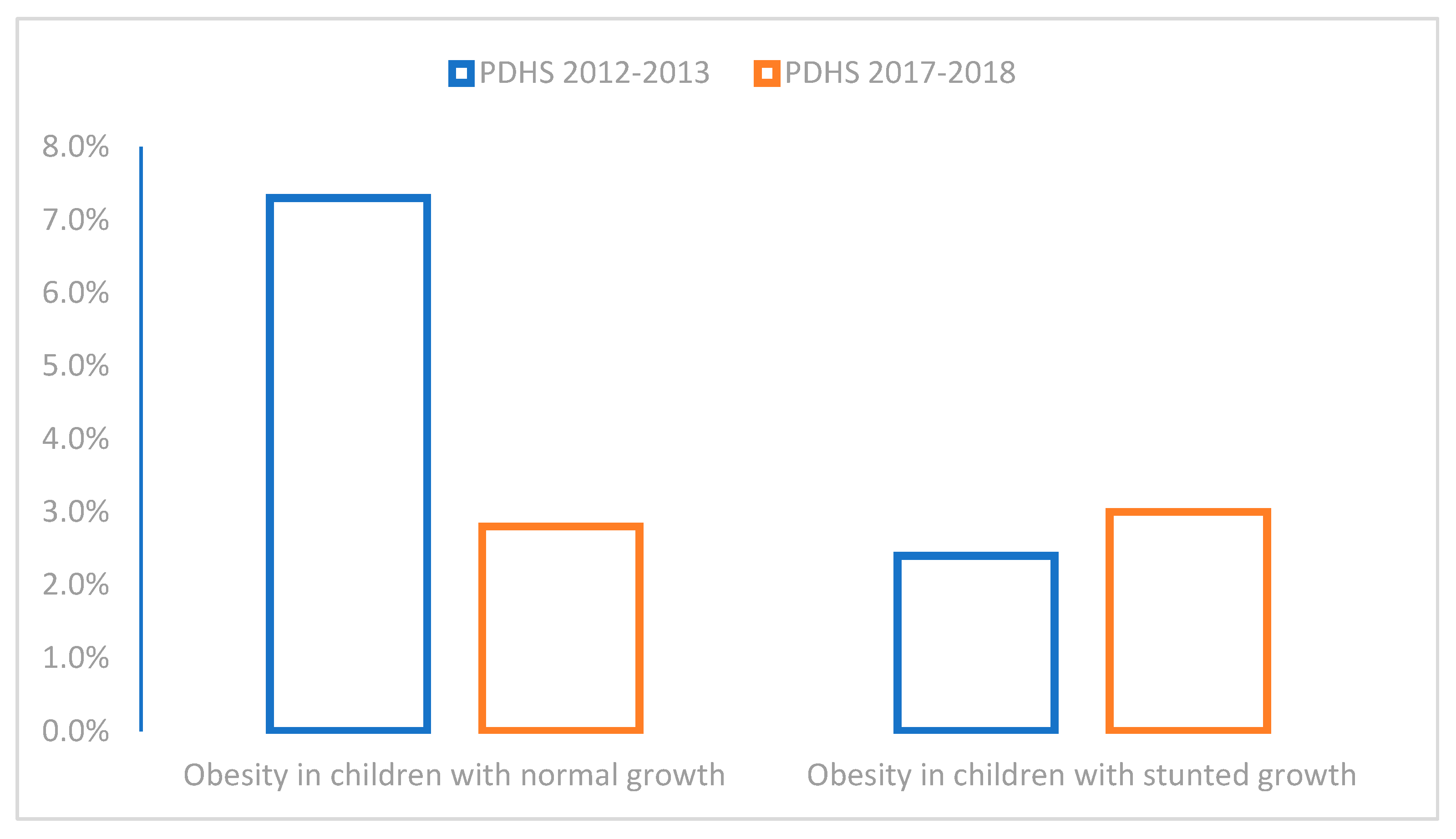

3.2. Prevalence and Trends of Paediatric Obesity

3.3. Paediatric Dietary and Feeding Practices Across Two Survey Periods

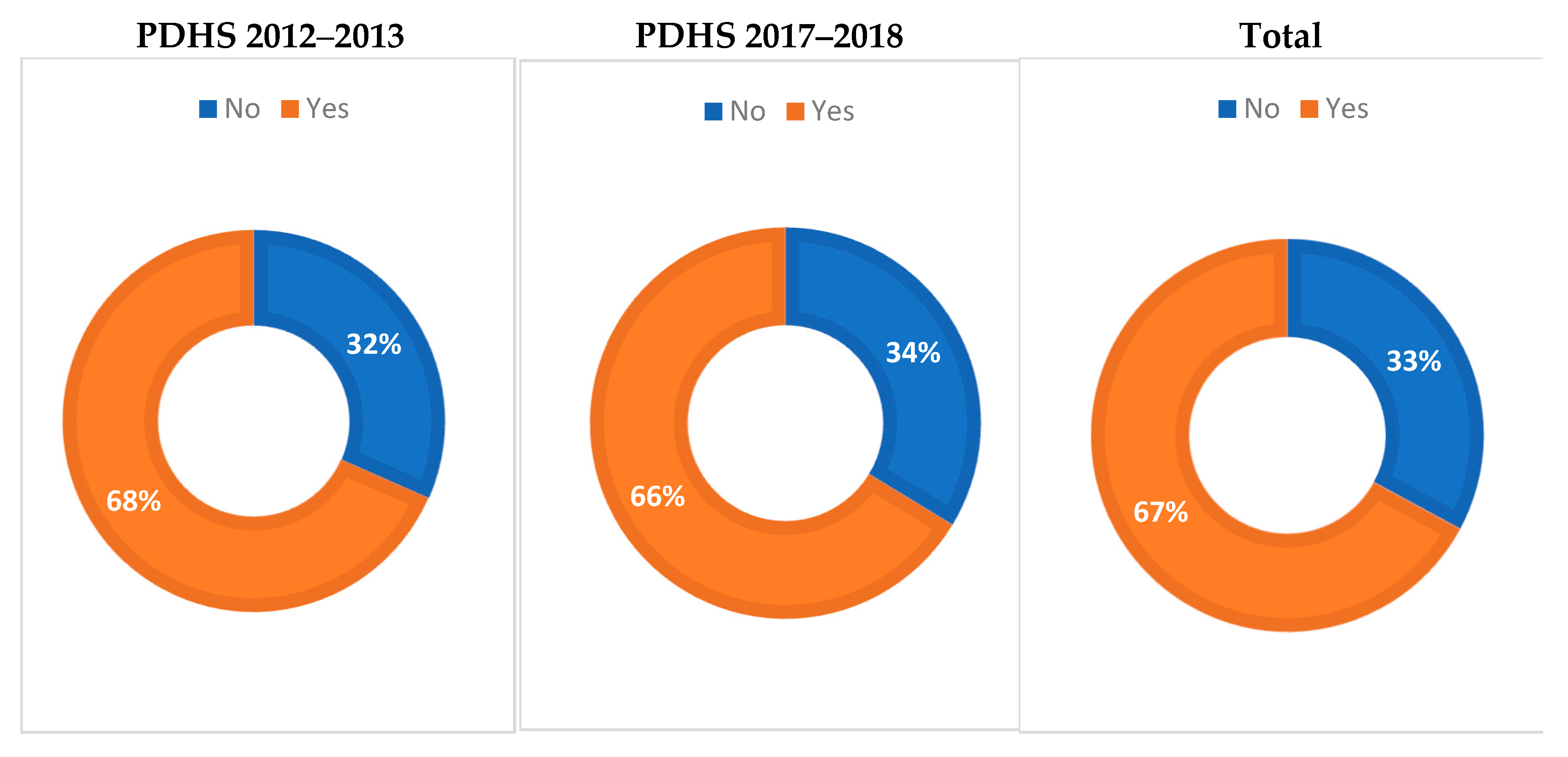

3.4. Meal Frequency Across Two Demographic Surveys of Pakistan

3.5. Relationships of Paediatric Obesity with Various Food Groups Among Children with Normal and Stunted Growth Trajectories

4. Discussion

4.1. Generalisability of Findings

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Study Recommendations

4.4. Future Research Directions

4.5. Implications for Public Health

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Victora, C.G.; Adair, L.; Fall, C.; Hallal, P.C.; Martorell, R.; Richter, L.; Sachdev, H.S.; Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group. Maternal and child undernutrition: Consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet 2008, 371, 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saavedra, J.M. Early nutrition, the development of obesity, and its long-term consequences. In Early Nutrition and Long-Term Health: Mechanisms, Consequences, and Opportunities, 2nd ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, Cambs, UK, 2022; pp. 437–491. [Google Scholar]

- Haroun, D.; ElSaleh, O.; Wood, L. Dietary and Activity Habits in Adolescents Living in the United Arab Emirates: A Cross-Sectional Study. Arab. J. Nutr. Exerc. 2017, 1, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, É.M.; Fangupo, L.J.; Cutfield, W.S.; Taylor, R.W. Systematic review of randomised controlled trials to improve dietary intake for the prevention of obesity in infants aged 0–24 months. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardwick, J.; Sidnell, A. Infant nutrition—Diet between 6 and 24 months, implications for paediatric growth, overweight and obesity. Nutr. Bull. 2014, 39, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapuano, K.M.; Tejavibulya, L.; Dinc, E.N.; Li, A.; Davis, H.; Korn, R.; Leibel, R.L.; Walsh, B.T.; Ranzenhofer, L.; Rosenbaum, M.; et al. Heightened sensitivity to high-calorie foods in children at risk for obesity: Insights from behavior, neuroimaging, and genetics. Brain Imaging Behav. 2023, 17, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewey, K.G.; Begum, K. Long-term consequences of stunting in early life. Matern. Child Nutr. 2011, 7, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, R.E.; Victora, C.G.; Walker, S.P.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Christian, P.; de Onis, M.; Ezzati, M.; Grantham-McGregor, S.; Katz, J.; Martorell, R.; et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013, 382, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pries, A.M.; Rehman, A.M.; Filteau, S.; Sharma, N.; Upadhyay, A.; Ferguson, E.L. Unhealthy snack food and beverage consumption is associated with lower dietary adequacy and length for-age z-scores among 12–23-month-old children in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 1843–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obesity and Overweight [Internet]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight? (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Hu, J.; Aris, I.M.; Lin, P.-I.D.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Perng, W.; Baidal, J.A.W.; Wen, D.; Oken, E. Longitudinal associations of modifiable risk factors in the first 1000 days with weight status and metabolic risk in early adolescence. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luque, V.; Mucarzel, F.; Hertogs, A.; Seed, P.T.; Flynn, A.C.; Poston, L.; Dalrymple, K.V. Associations between maternal diet, family eating habits and preschool children’s dietary patterns: Insights from the UPBEAT trial. Nutr. J. 2024, 23, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.B.; Moubarac, J.-C.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Rauber, F.; Khandpur, N.; Cediel, G.; Neri, D.; Martinez-Steele, E.; et al. Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, J.C.; Sawaya, A.L.; Wibaek, R.; Mwangome, M.; Poullas, M.S.; Yajnik, C.S.; Demaio, A. The double burden of malnutrition: Aetiological pathways and consequences for health. Lancet 2020, 395, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Kraak, V.I.; Allender, S.; Atkins, V.J.; Baker, P.I.; Bogard, J.R.; Brinsden, H.; Calvillo, A.; De Schutter, O.; Devarajan, R.; et al. The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet 2019, 393, 791–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziyab, A.H.; Karmaus, W.; Kurukulaaratchy, R.J.; Zhang, H.; Arshad, S.H. Developmental trajectories of Body Mass Index from infancy to 18 years of age: Prenatal determinants and health consequences. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2014, 68, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. Pakistan Nutrition Profile; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York City, NY, USA.

- Khan, D.S.A.; Das, J.K.; Zareen, S.; Lassi, Z.S.; Salman, A.; Raashid, M.; Dero, A.A.; Khanzada, A.; Bhutta, Z.A. Nutritional Status and Dietary Intake of School-Age Children and Early Adolescents: Systematic Review in a Developing Country and Lessons for the Global Perspective. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 739447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khaliq, A.; Nambiar, S.; Miller, Y.; Wraith, D. Adherence to complementary feeding indicators and their associations with coexisting forms of malnutrition in children aged between 6 to 23.9 months of age. J. Public Health 2025, 33, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, A.; Wraith, D.; Miller, Y.; Nambiar, S. Association of Infant Feeding Indicators and Infant Feeding Practices with Coexisting Forms of Malnutrition in Children under Six Months of Age. Nutrients. 2022, 14, 4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.; Arif, M.; Shah, A.A. Complementary feeding practices and associated factors among children aged 6-23 months in Pakistan. PLoS ONE. 2021, 16, e0247602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017–2018. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR354/FR354.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2012–2013. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR290/FR290.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Baidal, J.A.; Locks, L.M.; Cheng, E.R.; Blake-Lamb, T.L.; Perkins, M.E.; Taveras, E.M. Risk factors for childhood obesity in the first 1,000 days: A systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 50, 761–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaban Mohamed, M.A.; AbouKhatwa, M.M.; Saifullah, A.A.; Hareez Syahmi, M.; Mosaad, M.; Elrggal, M.E.; Dehele, I.S.; Elnaem, M.H. Risk factors, clinical consequences, prevention, and treatment of childhood obesity. Children 2022, 9, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victora, C.G.; Bahl, R.; Barros, A.J.D.; Franca, G.V.A.; Horton, S.; Krasevec, J.; Murch, S.; Sankar, M.J.; Walker, N.; Rollins, N.C.; et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 2016, 387, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Tomori, C.; Hernández-Cordero, S.; Baker, P.; Barros, A.J.D.; Bégin, F.; Chapman, D.J.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M.; McCoy, D.; Menon, P.; et al. Breastfeeding: Crucially important, but increasingly challenged in a market-driven world. Lancet 2023, 401, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamberti, L.M.; Fischer Walker, C.L.; Noiman, A.; Victora, C.; Black, R.E. Breastfeeding and the risk for diarrhea morbidity and mortality. BMC Public Health 2011, 11 (Suppl. 3), S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khan, M.N.; Islam, M.M. Effect of exclusive breastfeeding on selected adverse health and nutritional outcomes: A nationally representative study. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hadi, H.; Fatimatasari, F.; Irwanti, W.; Kusuma, C.; Alfiana, R.D.; Asshiddiqi, M.I.N.; Nugroho, S.; Lewis, E.C.; Gittelsohn, J. Exclusive Breastfeeding Protects Young Children from Stunting in a Low-Income Population: A Study from Eastern Indonesia. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hanif, H.M. Trends in breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices in Pakistan, 1990–2007. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2011, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khan, S.; Zaheer, S.; Safdar, N.F. Determinants of stunting, underweight and wasting among children < 5 years of age: Evidence from 2012–2013 Pakistan demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akombi, B.J.; Agho, K.E.; Merom, D.; Hall, J.J.; Renzaho, A.M. Multilevel Analysis of Factors Associated with Wasting and Underweight among Children Under-Five Years in Nigeria. Nutrients. 2017, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Das, S.; Gulshan, J. Different forms of malnutrition among under five children in Bangladesh: A cross sectional study on prevalence and determinants. BMC Nutr. 2017, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, G.; Dobe, M.; Ravi, M.D.; Verma, R.; Dutt, S.; Dutta, S.; Sehgal, S.; Complementary Feeding Consortium. Overcoming the Challenges of Complementary Feeding and the Potential Role of Fortified Infant Cereals: A Position Paper from India and Nepal. J. Pediatr. Perinatol. Child Health 2023, 7, 142–158. [Google Scholar]

- Nicklas, T.A.; O’Neil, C.E.; Fulgoni, V.L., 3rd. Nutrient intake, introduction of baby cereals and other complementary foods in the diets of infants and toddlers from birth to 23 months of age. AIMS Public Health 2020, 7, 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gardner, R.; Feely, A.; Layte, R.; Williams, J.; McGavock, J. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with an increased risk of obesity in early adolescence: A population-based prospective cohort study. Pediatr. Res. 2019, 86, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, M.R.; Rahman, M.S.; Khan, M.M.; Mondal, M.N.; Rahman, M.M.; Billah, B. Risk Factors for Child Malnutrition in Bangladesh: A Multilevel Analysis of a Nationwide Population-Based Survey. J. Pediatr. 2016, 172, 194–201.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asian Development Bank. Poverty Data: Pakistan. 2015. Available online: https://www.adb.org/countries/pakistan/poverty (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Ivanic, M.; Martin, W. Implications of higher global food prices for poverty in low-income countries. Agric. Econ. 2008, 39, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabnam, N.; Aurangzeb, N.; Riaz, S. Rising food prices and poverty in Pakistan. PLoS ONE. 2023, 18, e0292071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Variables | Categories | Total (n = 1230) | 2012–2013 (n = 467) | 2017–2018 (n = 763) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child factors | |||||

| Child’s age | 6 to11.9 months | 36.9% | 41.8% | 33.9% | 0.012 * |

| 12 to 17.9 months | 40.2% | 33.9% | 43.2% | ||

| 18 to 23.9 months | 22.8% | 22.7% | 22.9% | ||

| Sex | Male | 49.8% | 48.6% | 50.6% | 0.500 |

| Female | 50.2% | 51.4% | 49.4% | ||

| Birthweight | Normal weight | 17.4% | 16.6% | 17.8% | 0.431 |

| Low birthweight | 8% | 8.6% | 7.6% | ||

| Don’t know | 20.5% | 16.3% | 23.1% | ||

| Not weighted at birth | 54.1% | 58.5% | 51.4% | ||

| Birth size | Small or very small | 17% | 15.9% | 17.7% | 0.413 |

| Average or large | 83% | 84.1% | 82.3% | ||

| Diarrhoea | No | 70.8% | 71.0% | 70.6% | 0.885 |

| Yes | 29.2% | 29.0% | 29.4% | ||

| Fever | No | 55% | 54% | 55.7% | 0.552 |

| Yes | 45% | 46% | 44.3% | ||

| Cough | No | 57.5% | 61.9% | 54.8% | 0.014 * |

| Yes | 42.5% | 38.1% | 45.2% | ||

| Maternal factors | |||||

| Maternal age | Below 20 years | 4.4% | 3.4% | 5% | 0.417 |

| 20–34 years | 82.1% | 82.6% | 81.6% | ||

| 35 years or more | 13.5% | 14% | 13.4% | ||

| Maternal education | No education | 40.4% | 40.3% | 40.5% | 0.53 |

| Primary | 15.6% | 18% | 14.2% | ||

| Secondary | 25.4% | 26.6% | 24.8% | ||

| Higher | 18.5% | 15.2% | 20.6% | ||

| Working mother | No | 89.4% | 88.2% | 90.2% | 0.281 |

| Yes | 10.6% | 11.8% | 9.8% | ||

| Maternal body mass index | Normal weight | 48.5% | 56.6% | 43.6% | <0.001 * |

| Obese | 14.7% | 10.4% | 17.3% | ||

| Overweight | 27.1% | 22.3% | 30% | ||

| Underweight | 9.7% | 10.6% | 9.1% | ||

| Caesarean section | No | 78.5% | 83.3% | 75.5% | 0.002 * |

| Yes | 21.5% | 16.7% | 24.5% | ||

| Household factors | |||||

| Wealth index | Poorest | 13.9% | 13.1% | 14.4% | 0.006 * |

| Poorer | 20.1% | 16.7% | 22.1% | ||

| Middle | 21.1% | 19.5% | 22.1% | ||

| Richer | 20.8% | 25.7% | 17.8% | ||

| Richest | 24.1% | 25.1% | 23.5% | ||

| Family size | Small (1–4) | 32% | 33.2% | 30.7% | 0.335 |

| Medium (5–10) | 58.1% | 52% | 59.7% | ||

| Large (10+) | 10% | 14.8% | 9.6% | ||

| Community factors | |||||

| Region | ICT | 7.6% | 7.9% | 7.3% | <0.001 * |

| Punjab | 28.9% | 35.3% | 24.9% | ||

| Sindh | 16.3% | 17.1% | 15.9% | ||

| KPK | 28.6% | 33.2% | 25.8% | ||

| Baluchistan | 6.3% | 6.4% | 6.3% | ||

| FATA | 4.9% | - | 7.9% | ||

| AJK | 7.4% | - | 11.9% | ||

| Type of place of residence | Urban | 47.3% | 47.3% | 47.2% | 0.962 |

| Rural | 52.8% | 52.7% | 52.8% | ||

| Periodic factors | |||||

| Year | 2012 | 38% | - | - | - |

| 2017 | 62% | - | - | ||

| Food Group | Survey Years | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012–2013 (n = 467) | 2017–2018 (n = 763) | ||

| Breastmilk | 74.1% (70.1% to 78.1%) | 71% (67.7% to 74.2%) | 0.245 |

| Dairy products (animal milk, powder milk, yogurt, cheese, butter, etc.) | 54.4% (49.8% to 58.9%) | 54.3% (50.7% to 57.8%) | 0.708 |

| Cereals and grains | 71% (66.8% to 75.1%) | 72.1% (68.9% to 75.2%) | 0.965 |

| Lentils and nuts | 9.2% (6.5% to 11.8%) | 9.2% (7.1% to 11.5%) | 0.984 |

| Flesh foods (meats, chicken, organ meat, fish, and poultry) | 21.4% (17.6% to 25.1%) | 17.8% (15.1% to 20.5%) | 0.123 |

| Eggs | 27% (22.9% to 31.1%) | 29.5% (26.2% to 32.7%) | 0.343 |

| Vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables | 18.8% (15.2% to 22.3%) | 17.8% (15.1% to 20.5%) | 0.654 |

| Other fruits and vegetables | 38.8% (34.3% to 43.2%) | 32.8% (29.4% to 36.1%) | 0.033 |

| Variables | Categories | Overweight/Obese | Nutritional Paradox | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Odds | Adjusted Odds | Unadjusted Odds | Adjusted Odds | ||

| Dietary factors | |||||

| Breastmilk | No Yes | Ref. 0.55 (0.27 to 1.11) | Ref. 0.37 (0.16 to 0.85) * | Ref. 2.08 (0.96 to 4.48) | Ref. 3.71 (1.08 to 12.62) * |

| Dairy products | No Yes | Ref. 1.05 (0.53 to 2.09) | Ref. 0.73 (0.42 to 1.29) | ||

| Cereals and grains | No Yes | Ref. 1.51 (0.63 to 3.51) | Ref. 0.72 (0.39 to 1.29) | ||

| Lentils and nuts | No Yes | Ref. 0.28 (0.03 to 2.10) | Ref. 0.38 (0.09 to 1.60) | ||

| Flesh foods | No Yes | Ref. 1.28 (0.57 to 2.87) | Ref. 0.66 (0.29 to 1.49) | ||

| Eggs | No Yes | Ref. 0.88 (0.41 to 1.92) | Ref. 0.75 (0.39 to 1.46) | ||

| Vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables | No Yes | Ref. 0.74 (0.28 to 1.93) | Ref. 0.26 (0.08 to 0.87) * | ||

| Other fruits and vegetables | No Yes | Ref. 0.98 (0.40 to 2.41) | Ref. 1.12 (0.55 to 2.28) | ||

| Minimum meal frequency (MMF) | No Yes | Ref. 0.51 (0.23 to 1.14) | Ref 0.44 (0.19 to 0.99) * | Ref. 0.82 (0.41 to 1.60) | Ref. 1.06 (0.47 to 2.39) |

| Child factors | |||||

| Child month | 6 to 11.9 months 12 to 17.9 months 18 to 23.9 months | Ref. 0.88 (0.39 to 1.99) 1.31 (0.56 to 3.08) | Ref. 0.52 (0.27 to 0.99) * 0.46 (0.21 to 1.04) | ||

| Sex | Male Female | Ref. 0.99 (0.44 to 1.75) | Ref. 1.11 (0.63 to 1.96) | ||

| Birthweight | Normal LBW | Ref. 1.64 (0.50 to 5.31) | Ref. 2.29 (0.72 to 7.32) | ||

| Birth size | Normal size Small size | Ref. 1.28 (0.55 to 2.98) | Ref. 1.20 (0.59 to 2.45) | ||

| Diarrhoea | No Yes | Ref. 0.60 (0.26 to 1.40) | Ref. 0.57 (0.28 to 1.15) | ||

| Fever | No Yes | Ref. 1.49 (0.75 to 2.97) | Ref. 0.25 (0.12 to 0.52) * | ||

| Cough | No Yes | Ref. 1.48 (0.74 to 2.93) | Ref. 0.36 (0.18 to 0.71) * | ||

| Maternal factors | |||||

| Maternal age | Below 20 years 20–34 years 35 years or more | Ref. 0.67 (0.15 to 2.93) 0.95 (0.18 to 4.88) | Ref. 0.71 (0.21 to 2.37) 0.74 (0.18 to 2.98) | ||

| Maternal education | No education Primary Secondary Higher | Ref. 0.75 (0.24 to 2.35) 0.92 (0.37 to 2.26) 1.46 (0.61 to 3.47) | Ref. 0.36 (0.13 to 0.93) * 0.26 (0.11 to 0.64) * 0.37 (0.15 to 0.91) * | ||

| Working mothers | No Yes | Ref. 0.25 (0.03 to 1.85) | Ref. 1.10 (0.46 to 2.64) | ||

| Maternal body mass index | Normal weight Obese Overweight Underweight | Ref. 1.99 (0.81 to 4.90) 1.52 (0.67 to 3.45) 0.73 (0.16 to 3.29) | Ref. 0.31 (0.09 to 1.04) 0.93 (0.50 to 1.73) 0.15 (0.02 to 1.13) | ||

| Caesarean section | No Yes | Ref. 2.26 (1.11 to 4.58) * | Ref. 2.21 (1.01 to 5.05) * | Ref. 0.48 (0.21 to 1.15) | |

| Household factors | |||||

| Wealth index | Poorest Poorer Middle Richer Richest | Ref. 0.89 (0.27 to 2.85) 0.59 (0.16 to 2.07) 0.72 (0.21 to 2.41) 1.18 (0.40 to 3.46) | Ref. 0.30 (0.13 to 0.68) * 0.18 (0.07 to 0.47) * 0.19 (0.07 to 0.48) * 0.31 (0.14 to 0.67) * | ||

| Family size | Small (1–4) Medium (5–10) Large (10+) | Ref. 1.63 (0.37 to 7.09) 1.93 (0.42 to 8.75) | Ref. 1.18 (0.41 to 3.43) 1.44 (0.47 to 4.39) | ||

| Community factors | |||||

| Type of place of residence | Urban Rural | Ref. 1.15 (0.57 to 2.28) | Ref. 1.29 (0.73 to 2.29) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khaliq, A.; Usmani, I.A.; Rizwan, Y.; Khan, M.; Khan, A.S.; Saleem, N.u.A.; Junaid, M. Cross-Sectional Analysis of Food Group Consumption and Obesity in Children Aged 6–23 Months with Normal and Stunted Growth Patterns in Pakistan. Obesities 2025, 5, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5030055

Khaliq A, Usmani IA, Rizwan Y, Khan M, Khan AS, Saleem NuA, Junaid M. Cross-Sectional Analysis of Food Group Consumption and Obesity in Children Aged 6–23 Months with Normal and Stunted Growth Patterns in Pakistan. Obesities. 2025; 5(3):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5030055

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhaliq, Asif, Izzan Ahmed Usmani, Yusra Rizwan, Mishaim Khan, Akif Shahid Khan, Noor ul Ain Saleem, and Muhammad Junaid. 2025. "Cross-Sectional Analysis of Food Group Consumption and Obesity in Children Aged 6–23 Months with Normal and Stunted Growth Patterns in Pakistan" Obesities 5, no. 3: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5030055

APA StyleKhaliq, A., Usmani, I. A., Rizwan, Y., Khan, M., Khan, A. S., Saleem, N. u. A., & Junaid, M. (2025). Cross-Sectional Analysis of Food Group Consumption and Obesity in Children Aged 6–23 Months with Normal and Stunted Growth Patterns in Pakistan. Obesities, 5(3), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5030055