Modularisation Analysis for Scaling Hydrogen Production: High-Power Single-Electrolyser vs. Multiple-Smaller-Electrolyser Plants

Abstract

1. Introduction

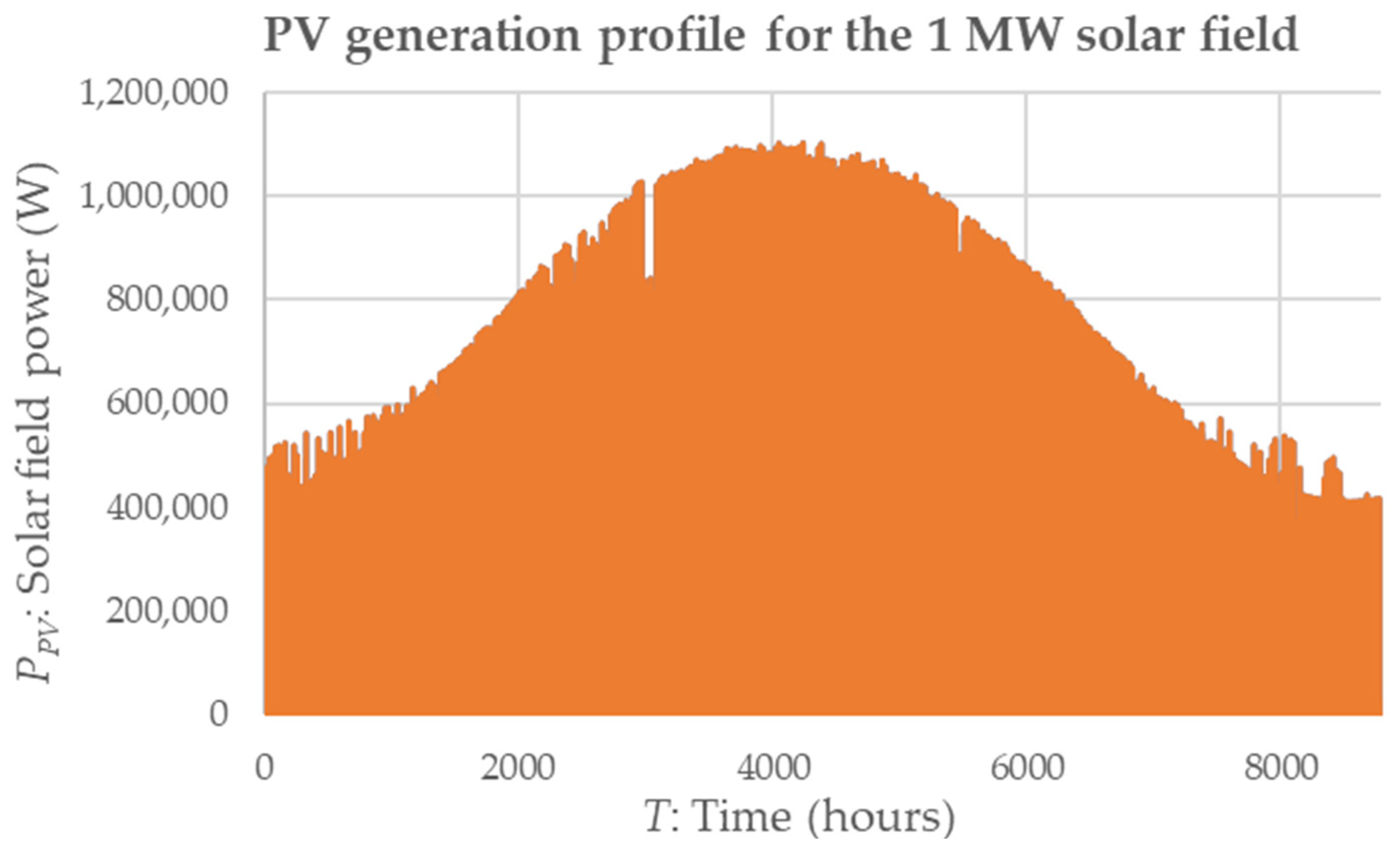

2. Materials and Methods

- -

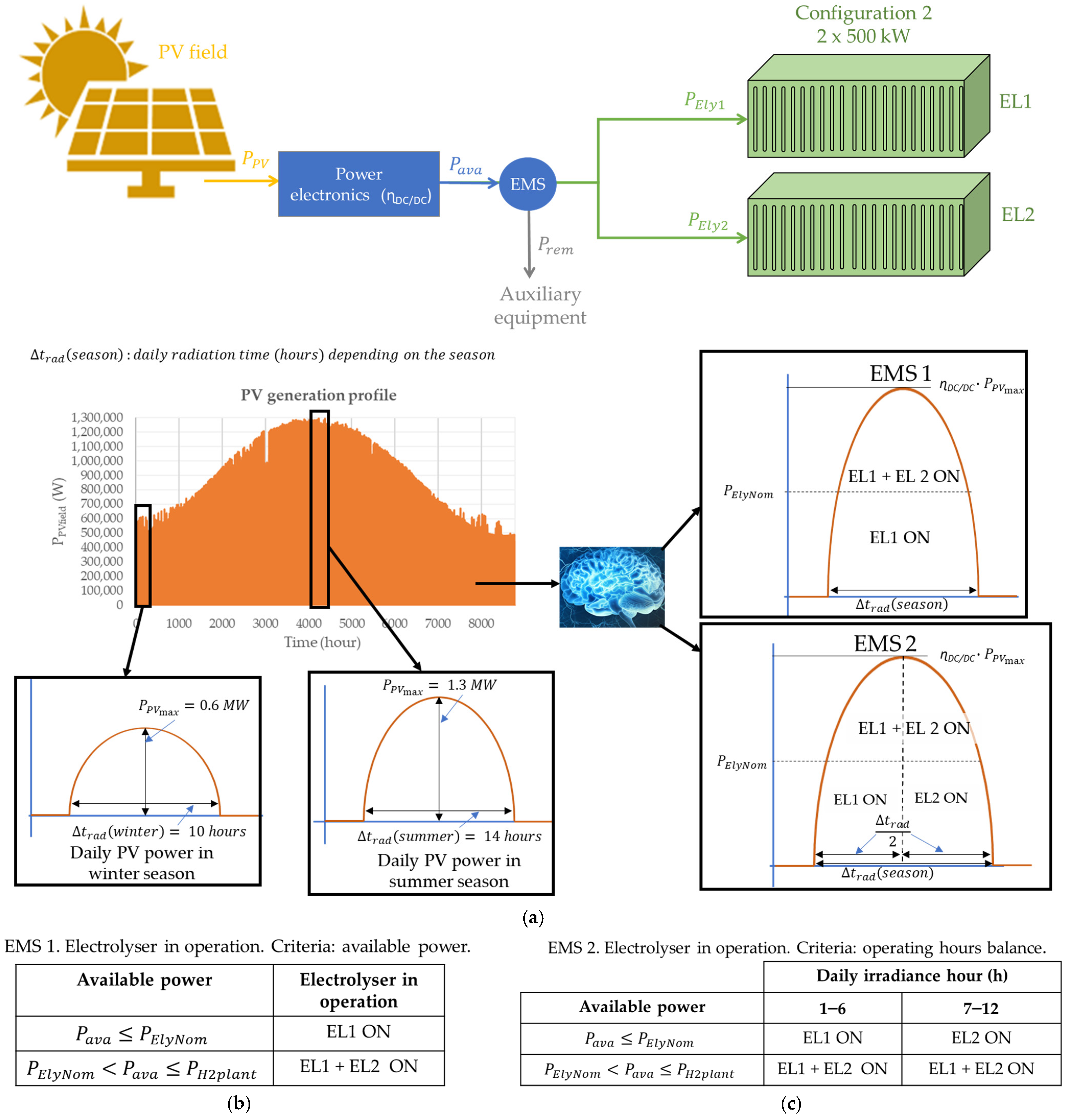

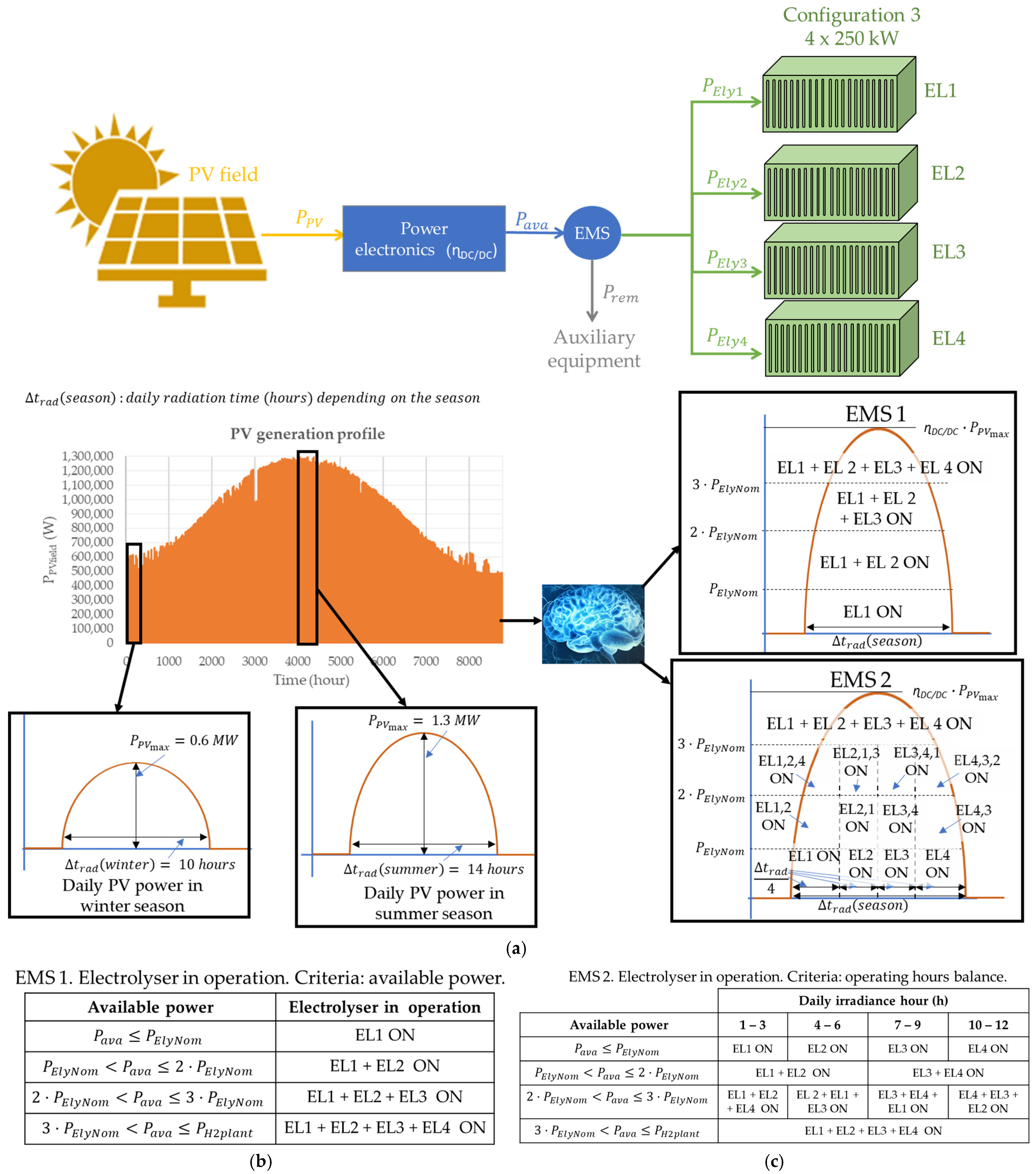

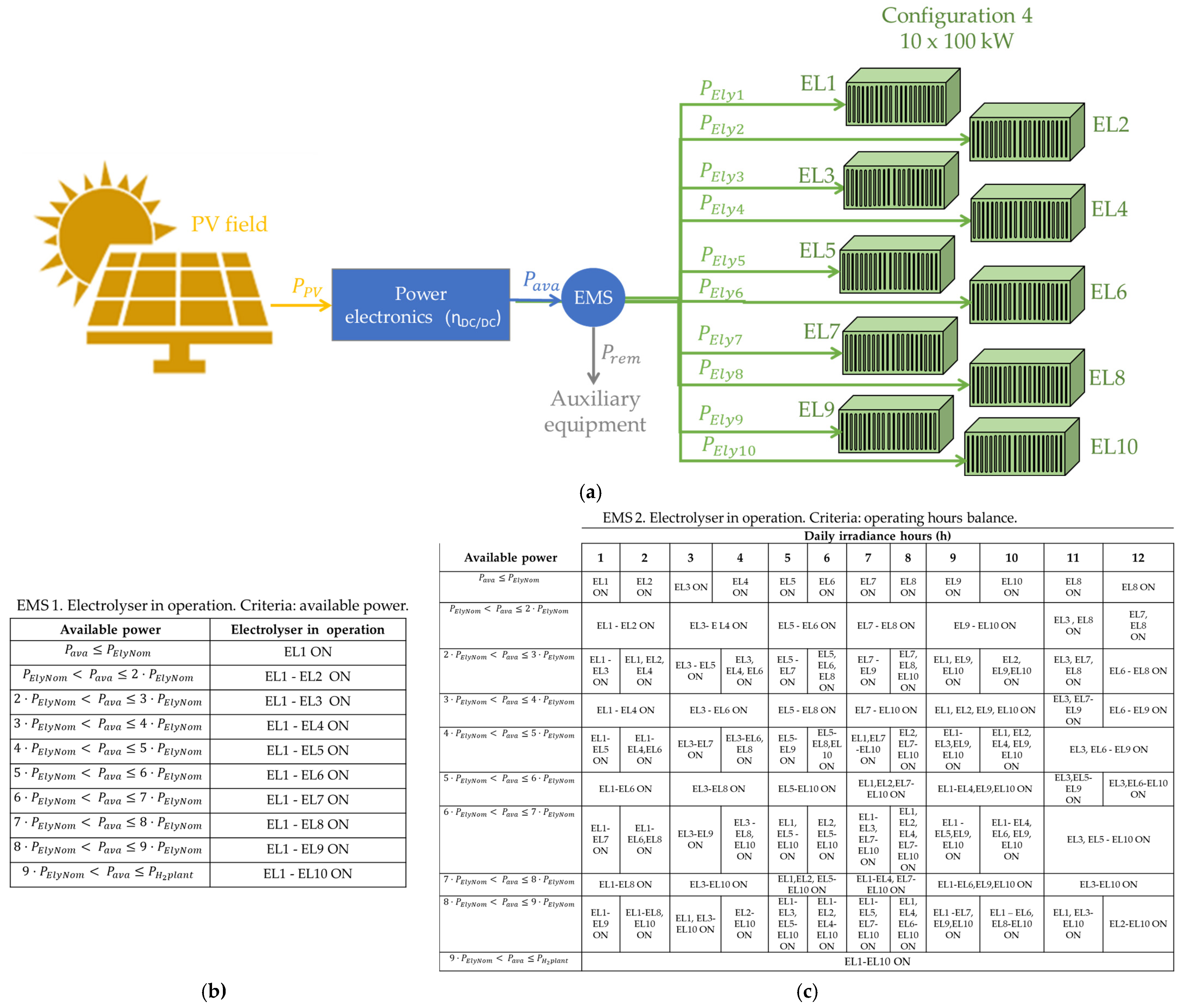

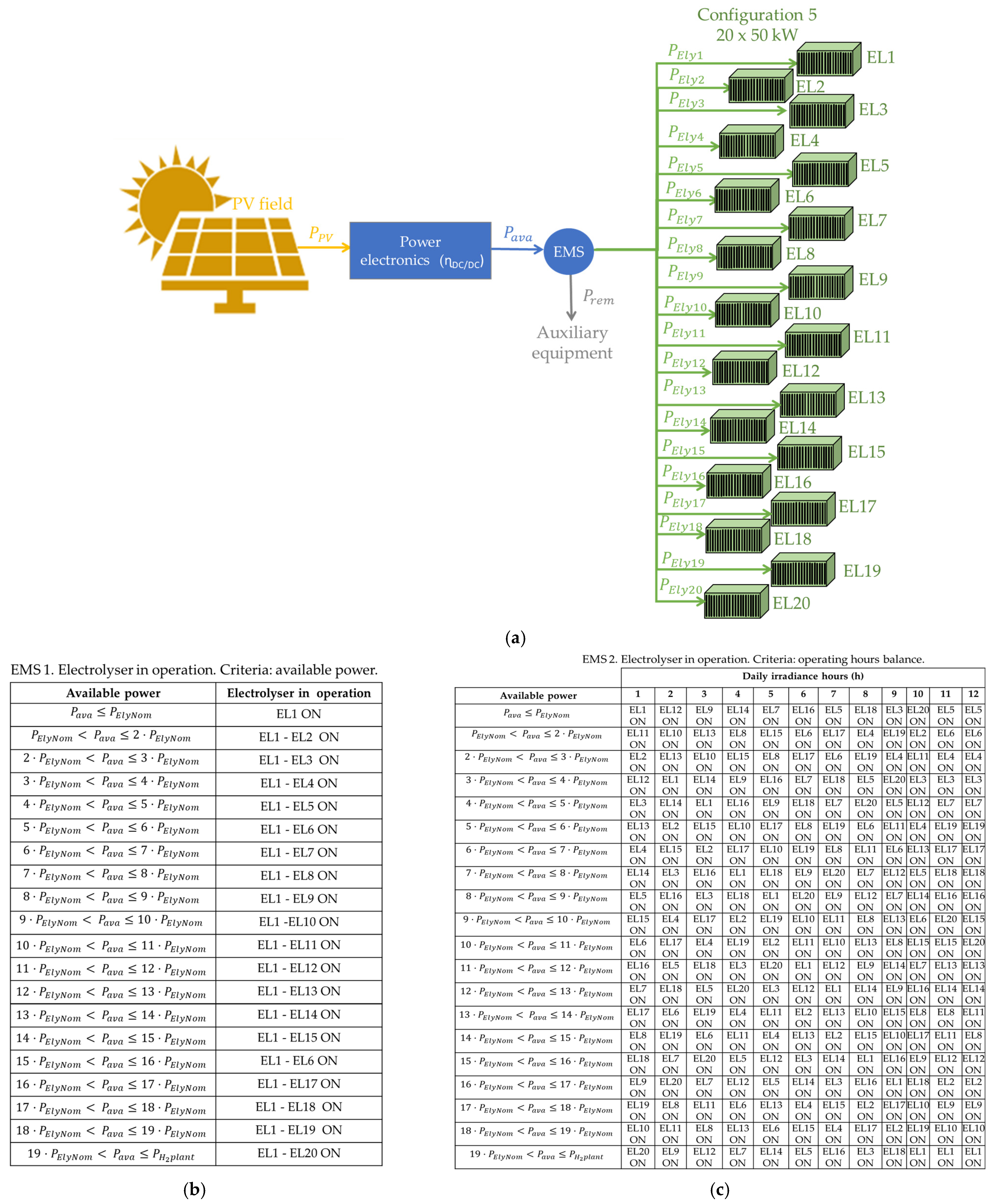

- EMS 1 is based on available power criteria. It analyses the available power to determine whether the electrolyser or electrolysers should be started up. That is, for example, in configuration 2 (×2—500 kW), if the available power is lower than 500 kW, electrolyser EL1 is ON, and EL2 is OFF. However, if the available power is greater than 500 kW, both EL1 and EL2 are ON.

- -

- EMS 2 is based on operating hours’ balance. It distributes the operating hours of each electrolyser equally. In other words, given that the hydrogen production plant is supplied by a photovoltaic field located in Huelva, in southwestern Spain, the average daily duration of solar irradiation is 12 h. Therefore, EMS 2 puts EL1 ON from hour 1 to hour 6, and EL2 ON from hour 7 to hour 12.

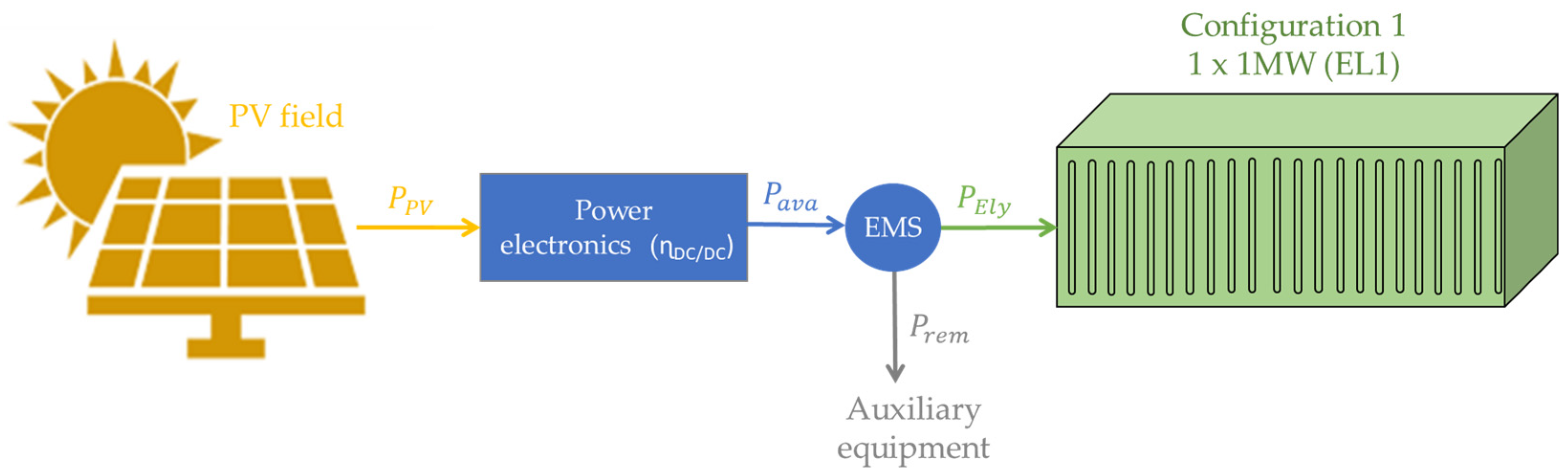

3. Configuration Design: Developed Architectures

3.1. Configuration 1: Modularisation Level 1

3.2. Configuration 2: Modularisation Level 2

3.3. Configuration 3: Modularisation Level 4

3.4. Configuration 4: Modularisation Level 10

3.5. Configuration 5: Modularisation Level 20

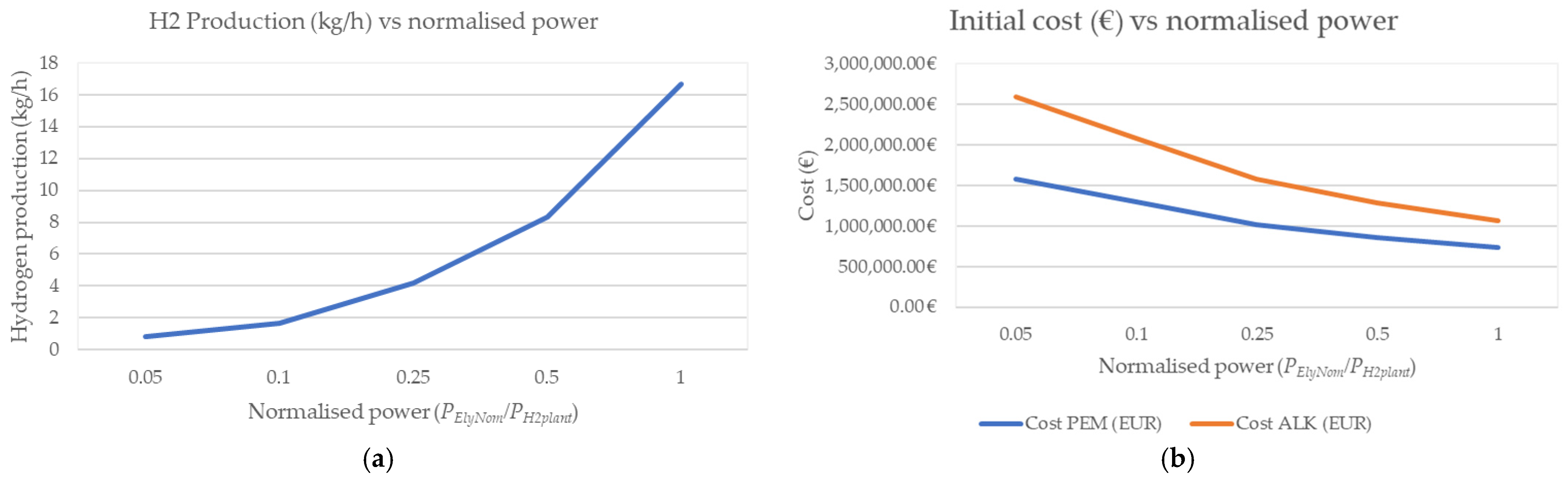

4. Techno-Economic Study: Analysis Seeking Optimal Modularisation

| Configuration | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMS 1 | EMS 2 | EMS 1 | EMS 2 | EMS 1 | EMS 2 | EMS 1 | EMS 2 | ||

| Economic losses alkaline electrolysis (50–83 kWh/kg) (€) | 27,825–46,189 Δ = 18,904 | 22,659–37,613 Δ = 14,954 | 19,221–32,085 Δ = 12,864 | 16,816–30,789 Δ = 13,973 | 18,183–30,184 Δ = 12,001 | ||||

| Economic losses alkaline electrolysis (3–21 days’ replacement time) (€) | 16,496–115,474 Δ = 98,978 | 13,433–94,033 Δ = 80,600 | 11,395–80,213 Δ = 68,818 | 10,468–76,974 Δ = 66,506 | 10,780–75,460 Δ = 64,680 | ||||

| Economic losses alkaline electrolysis (2–6 €/kg H2) (€) | 15,396–46,189 Δ = 30,793 | 12,538–37,613 Δ = 25,075 | 10,635–32,085 Δ = 21,450 | 9770–30,789 Δ = 21,019 | 10,061–30,184 Δ = 20,123 | ||||

| Economic losses PEM electrolysis (50–78 kWh/kg) (€) | 28,634–47,534 Δ = 18,900 | 22,890–37,997 Δ = 15,107 | 20,036–33,274 Δ = 13,238 | 18,269–31,367 Δ = 13,098 | 18,326–30,422 Δ = 12,096 | ||||

| Economic losses PEM electrolysis (3–21 days’ replacement time) (€) | 16,976–118,835 Δ = 101,859 | 13,570–94,992 Δ = 81,422 | 11,879–83,184 Δ = 71,305 | 10,831–78,416 Δ = 67,585 | 10,865–76,054 Δ = 65,189 | ||||

| Economic losses PEM electrolysis (2–6 €/kg H2) (€) | 15,845–47,534 Δ = 31,689 | 12,665–37,997 Δ = 25,332 | 11,087–33,274 Δ = 22,187 | 10,109–31,367 Δ = 21,258 | 10,141–30,422 Δ = 20,281 | ||||

| Configuration 1 | Configuration 2 | Configuration 3 | Configuration 4 | Configuration 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrolysis Technology | Lifetime (Hours) | EMS 1 H2 Production (kg) | EMS 1 H2 Production (kg) | EMS 2 H2 Production (kg) | EMS 1 H2 Production (kg) | EMS 2 H2 Production (kg) | EMS 1 H2 Production (kg) | EMS 2 H2 Production (kg) | EMS 1 H2 Production (kg) | EMS 2 H2 Production (kg) |

| PEM | 10,000 | 1,035,558 | 1,034,737 | 1,034,737 | 1,035,146 | 1,035,558 | 1,035,368 | 1,035,558 | 1,035,558 | 1,035,558 |

| 40,000 | 1,035,558 | 1,034,737 | 1,034,737 | 1,035,146 | 1,035,558 | 1,035,368 | 1,035,558 | 1,035,558 | 1,035,558 | |

| 70,000 | 1,035,558 | 1,034,737 | 1,034,737 | 1,035,146 | 1,035,558 | 1,035,368 | 1,035,558 | 1,035,558 | 1,035,558 | |

| 100,000 | 1,035,558 | 1,034,737 | 1,034,737 | 1,035,146 | 1,035,558 | 1,035,368 | 1,035,558 | 1,035,558 | 1,035,558 | |

| ALK | 10,000 | 1,006,273 | 1,024,289 | 1,024,289 | 1,029,777 | 1,035,558 | 1,031,954 | 1,013,568 | 1,035,558 | 1,035,558 |

| 40,000 | 1,006,273 | 1,024,289 | 1,024,289 | 1,029,777 | 1,035,558 | 1,031,954 | 1,013,568 | 1,035,558 | 1,035,558 | |

| 70,000 | 1,006,273 | 1,024,289 | 1,024,289 | 1,029,777 | 1,035,558 | 1,031,954 | 1,013,568 | 1,035,558 | 1,035,558 | |

| 100,000 | 1,006,273 | 1,024,289 | 1,024,289 | 1,029,777 | 1,035,558 | 1,031,954 | 1,013,568 | 1,035,558 | 1,035,558 | |

| Configuration 1 | Configuration 2 | Configuration 3 | Configuration 4 | Configuration 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrolysis Technology | Lifetime (Hours) | EMS 1 LCOH (€/kg) | EMS 1 LCOH (€/kg) | EMS 2 LCOH (€/kg) | EMS 1 LCOH (€/kg) | EMS 2 LCOH (€/kg) | EMS 1 LCOH (€/kg) | EMS 2 LCOH (€/kg) | EMS 1 LCOH (€/kg) | EMS 2 LCOH (€/kg) |

| PEM | 10,000 | 4.07 | 3.95 | 4.08 | 3.99 | 4.82 | 4.82 | 5.83 | 5.77 | 5.77 |

| 40,000 | 1.51 | 1.61 | 1.84 | 1.79 | 2.31 | 2.21 | 2.81 | 2.69 | 2.69 | |

| 70,000 | 1.25 | 1.40 | 1.65 | 1.65 | 2.11 | 2.03 | 2.57 | 2.48 | 2.48 | |

| 100,000 | 1.24 | 1.40 | 1.62 | 1.59 | 2.06 | 2.03 | 2.52 | 2.48 | 2.48 | |

| ALK | 10,000 | 9.70 | 9.43 | 9.45 | 10.48 | 10.13 | 13.04 | 13.25 | 15.76 | 16.03 |

| 40,000 | 3.38 | 3.52 | 3.52 | 3.99 | 3.68 | 4.87 | 4.94 | 6.03 | 6.01 | |

| 70,000 | 2.51 | 2.52 | 2.51 | 3.06 | 2.75 | 4.03 | 3.34 | 4.91 | 4.06 | |

| 100,000 | 1.71 | 2.50 | 2.04 | 2.76 | 2.47 | 3.57 | 3.34 | 4.42 | 4.06 | |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BoP | Balance of plant |

| Unit cost of the hydrogen production plant (€/kW) | |

| CAPEX | Capital expenditure |

| Selling unitary cost of green hydrogen (5 €/kg) | |

| Economic losses (€) | |

| Energy needed by the electrolyser to produce 1 kg hydrogen (50–83 kWh/kg) | |

| EMS | Energy management strategy |

| EoL | End of life |

| Fitting constant | |

| k | Fitting constant |

| Levelized cost of hydrogen (€/kg) | |

| MSELS | Multi-stack electrolyser system |

| MSFC | Multi-stack fuel cell |

| Number of replacements | |

| O&M | Operation and maintenance |

| Available power (kW) | |

| Individual module’s electrolyser power (kW) | |

| PEM | Polymer exchange membrane |

| Nominal electrical power of the hydrogen production plant (1 MW) | |

| PV field power (W) | |

| Hydrogen production during hydrogen electrolyser plant lifetime (kg) | |

| Annual hydrogen production in the plant (kg) | |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| Nominal capacity of the electrolyser module (kW) | |

| Lifespan of the hydrogen production plant (25 years) | |

| Unit of time (1 h) | |

| Electrolyser replacement time (years) | |

| Installation year of the hydrogen production plant | |

| Reference year (2020) | |

| Scaling factor | |

| Learning factor |

References

- Guan, D.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Shi, R.; Jiao, K.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Xie, B.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, J.; et al. Hydrogen society: From present to future. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 4926–4943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompodakis, E.E.; Orfanoudakis, G.I.; Katsigiannis, Y.A.; Karapidakis, E.S. Hydrogen Production from Wave Power Farms to Refuel Hydrogen-Powered Ships in the Mediterranean Sea. Hydrogen 2024, 5, 494–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompodakis, E.E.; Papadimitriou, T. Techno-Economic Assessment of Pink Hydrogen Produced from Small Modular Reactors for Maritime Applications. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtolo, S.; Tetteh, E.K.; Mthombeni, N.H.; Moloi, K.; Rathilal, S. Optimization of Green Hydrogen Production via Direct Seawater Electrolysis Powered by Hybrid PV-Wind Energy: Response Surface Methodology. Energies 2025, 18, 5328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminaho, E.N.; Aminaho, N.S.; Aminaho, F. Techno-economic assessments of electrolyzers for hydrogen production. Appl. Energy 2025, 399, 126515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, O.; Alamdari, P.; Jahangiri, M.; Sedaghat, A.; Alemrajabi, A.A. A techno-economical assessment of solar/wind resources and hydrogen production: A case study with GIS maps. Energy 2019, 175, 914–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genç, M.S.; Çelik, M.; Karasu, İ. A review on wind energy and wind–hydrogen production in Turkey: A case study of hydrogen production via electrolysis system supplied by wind energy conversion system in Central Anatolian Turkey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 6631–6646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wappler, M.; Unguder, D.; Lu, X.; Ohlmeyer, H.; Teschke, H.; Lueke, W. Building the green hydrogen market–Current state and outlook on green hydrogen demand and electrolyzer manufacturing. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 33551–33570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Zhao, W.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Zhou, H. Large scale of green hydrogen storage: Opportunities and challenges. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 50, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bade, S.O.; Tomomewo, O.S.; Meenakshisundaram, A.; Ferron, P.; Oni, B.A. Economic, social, and regulatory challenges of green hydrogen production and utilization in the US: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 49, 314–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabi, A.G.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Mahmoud, M.S.; Elsaid, K.; Obaideen, K.; Rezk, H.; Wilberforce, T.; Eisa, T.; Chae, K.-J.; Sayed, E.T. Green hydrogen: Pathways, roadmap, and role in achieving sustainable development goals. Pro. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 177, 664–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg, M.J.; Esposito, D.V.; Fthenakis, V.M. Designing off-grid green hydrogen plants using dynamic polymer electrolyte membrane electrolyzers to minimize the hydrogen production cost. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.; Koning, V.; Theodorus de Groot, M.; de Groot, A.; Mendoza, P.G.; Junginger, M.; Kramer, G.J. Present and future cost of alkaline and PEM electrolyser stacks. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 32313–32330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Díaz, M.T.; Chávez Oróstica, H.; Guajardo, J. Economic Analysis: Green Hydrogen Production Systems. Processes 2023, 11, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, L.A.; Leonard, A.; Trotter, P.A.; Hirmer, S. Green hydrogen production and use in low- and middle-income countries: A least-cost geospatial modelling approach applied to Kenya. Appl. Energy 2023, 343, 121219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, M.; Hassan, H. Egyptian green hydrogen Atlas based on available wind/solar energies: Power, hydrogen production, cost, and CO2 mitigation maps. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 59, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan-Van, L.; Dinh, V.N.; Felici, R.; Duc, T.N. New models for feasibility assessment and electrolyser optimal sizing of hydrogen production from dedicated wind farms and solar photovoltaic farms, and case studies for Scotland and Vietnam. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 295, 117597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reksten, A.H.; Thomassen, M.S.; Møller-Holst, S.; Sundseth, K. Projecting the future cost of PEM and alkaline water electrolysers; a CAPEX model including electrolyser plant size and technology development. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 38106–38113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrenti, I.; Zheng, Y.; Singlitico, A.; You, S. Low-carbon and cost-efficient hydrogen optimisation through a grid-connected electrolyser: The case of GreenLab skive. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 171, 113033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyeen, S.M.; Takahashi, R.; Tamura, J. Electrolyzer switching strategy for hydrogen generation from variable speed wind generator. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2011, 81, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Du, B.; Zhou, S.; Zhu, W.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xie, C.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, L.; Song, J.; et al. Optimization of power allocation for wind-hydrogen system multi-stack PEM water electrolyzer considering degradation conditions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 5850–5872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L. Record breaker|World’s Largest Green Hydrogen Project, with 150 MW Electrolyser, Brought on Line in China. Recharg Glob News Intell Energy Transit, 1 February 2022. Available online: https://www.rechargenews.com/energy-transition/record-breaker-world-s-largest-green-hydrogen-project-with-150mw-electrolyser-brought-on-line-in-china/2-1-1160799 (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- Plug Power Inc. Plug Power Makes Major Strategic Move into Finland’s Green Hydrogen Economy with its Proven PEM Electrolyzer and Liquefaction Technology. GlobeNewswire, 30 May 2023. Available online: https://www.ir.plugpower.com/press-releases/news-details/2023/Plug-Power-Makes-Major-Strategic-Move-into-Finlands-Green-Hydrogen-Economy-with-its-Proven-PEM-Electrolyzer-and-Liquefaction-Technology/default.aspx (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- Egyptian Consortium Kicks off 100 MW Electrolyser Project. ReNEWS, 8 November 2022. Available online: https://renews.biz/81678/egyptian-consortium-kicks-of-100mw-electrolyser-project/ (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- H2B2 Electrolysis Technologies Vigo Free Trade Zone Consortium Will Have a Green Hydrogen Plant Thanks to H2B2 and ImesAPI. H2B2, 28 March 2023. Available online: https://www.h2b2.es/vigo-free-trade-zone-consortium/ (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- International Energy Agency. Global Hydrogen Review 2023; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Lopez, V.A.; Ziar, H.; Haverkort, J.W.; Zeman, M.; Isabella, O. Dynamic operation of water electrolyzers: A review for applications in photovoltaic systems integration. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 182, 113407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrario, A.M.; Vivas, F.J.; Manzano, F.S.; Andújar, J.M.; Bocci, E.; Martirano, L. Hydrogen vs. Battery in the long-term operation. A comparative between energy management strategies for hybrid renewable microgrids. Electronics 2020, 9, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, J.; Segura, F.; Andújar, J.M. Green Hydrogen: Resources Consumption, Technological Maturity, and Regulatory Framework. Energies 2023, 16, 6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, J.; Segura, F.; Andújar, J.M.; Ferrario, A.M. The Economic Impact and Carbon Footprint Dependence of Energy Management Strategies in Hydrogen-Based Microgrids. Electronics 2023, 12, 3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zekalabs RedPrime 25 kW, 800 V, 120 A DC-DC Converter. Available online: https://zekalabs.com/products/isolated-power-converters/dc-dc-isolated-converter-25kw-120a/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Carmo, M.; Fritz, D.L.; Mergel, J.; Stolten, D. A comprehensive review on PEM water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 4901–4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.; Lee, B.; Lee, H.; Byun, M.; Cho, H.S.; Cho, W.; Kim, C.H.; Brigljević, B.; Lim, H. Impact of voltage degradation in water electrolyzers on sustainability of synthetic natural gas production: Energy, economic, and environmental analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 245, 114516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantinou, G.; Algara-Siller, G.; Teschner, D.; Vidaković-Koch, T.; Schlögl, R.; Sundmacher, K. Degradation study of a proton exchange membrane water electrolyzer under dynamic operation conditions. Appl. Energy 2020, 280, 115911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiß, A.; Siebel, A.; Bernt, M.; Shen, T.-H.; Tileli, V.; Gasteiger, H.A. Impact of Intermittent Operation on Lifetime and Performance of a PEM Water Electrolyzer. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, F487–F497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttler, A.; Spliethoff, H. Current status of water electrolysis for energy storage, grid balancing and sector coupling via power-to-gas and power-to-liquids: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2440–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, M.; Banaszek, L.; Magee, C.; Rivero-Hudec, M. Economic Lifetimes of Solar Panels. Procedia CIRP 2022, 105, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artaş, S.B.; Kocaman, E.; Bilgiç, H.H.; Tutumlu, H.; Yağlı, H.; Yumrutaş, R. Why PV panels must be recycled at the end of their economic life span? A case study on recycling together with the global situation. Pro. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 174, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsad, A.Z.; Hannan, M.A.; Al-Shetwi, A.Q.; Begum, R.A.; Hossain, M.J.; Ker, P.J.; Mahlia, T.I. Hydrogen electrolyser technologies and their modelling for sustainable energy production: A comprehensive review and suggestions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 27841–27871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yodwong, B.; Guilbert, D.; Phattanasak, M.; Kaewmanee, W.; Hinaje, M.; Vitale, G. AC-DC Converters for Electrolyzer Applications: State of the Art and Future Challenges. Electronics 2020, 9, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Green Hydrogen Cost Reduction Scaling Up Electrolysers to Meet the 1.5 °C Climate Goal. Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2020/Dec/IRENA_Green_hydrogen_cost_2020.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Vivas, F.J.; Segura, F.; Andújar, J.M.; Caparrós, J.J. A suitable state-space model for renewable source-based microgrids with hydrogen as backup for the design of energy management systems. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 219, 113053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.P.; Clipsham, J.; Chavushoglu, H.; Rowley-Neale, S.J.; Banks, C.E. Polymer electrolyte electrolysis: A review of the activity and stability of non-precious metal hydrogen evolution reaction and oxygen evolution reaction catalysts. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 139, 110709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Khan, M.H.; Daiyan, R.; Han, Z.; Hablutzel, M.; Haque, N.; Amal, R.; MacGill, I. Designing optimal integrated electricity supply configurations for renewable hydrogen generation in Australia. iScience 2021, 24, 102539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clean Hydrogen Partnership. Mission Innovation Hydrogen Cost and Sales Prices. Available online: https://h2v.eu/analysis/statistics/financing/hydrogen-cost-and-sales-prices (accessed on 19 December 2023).

| Reference | Modularisation Study | Modularity Impact on CAPEX Reduction | Modular Green Hydrogen Production Plant Economic Study | Economic Impact Based on EMS | Discerning ALK and PEM Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [12,14,15,16] | No | No | No | No | No |

| [13] | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| [17] | No * | No | No | No | No |

| [20,21] | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Authors’ proposal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

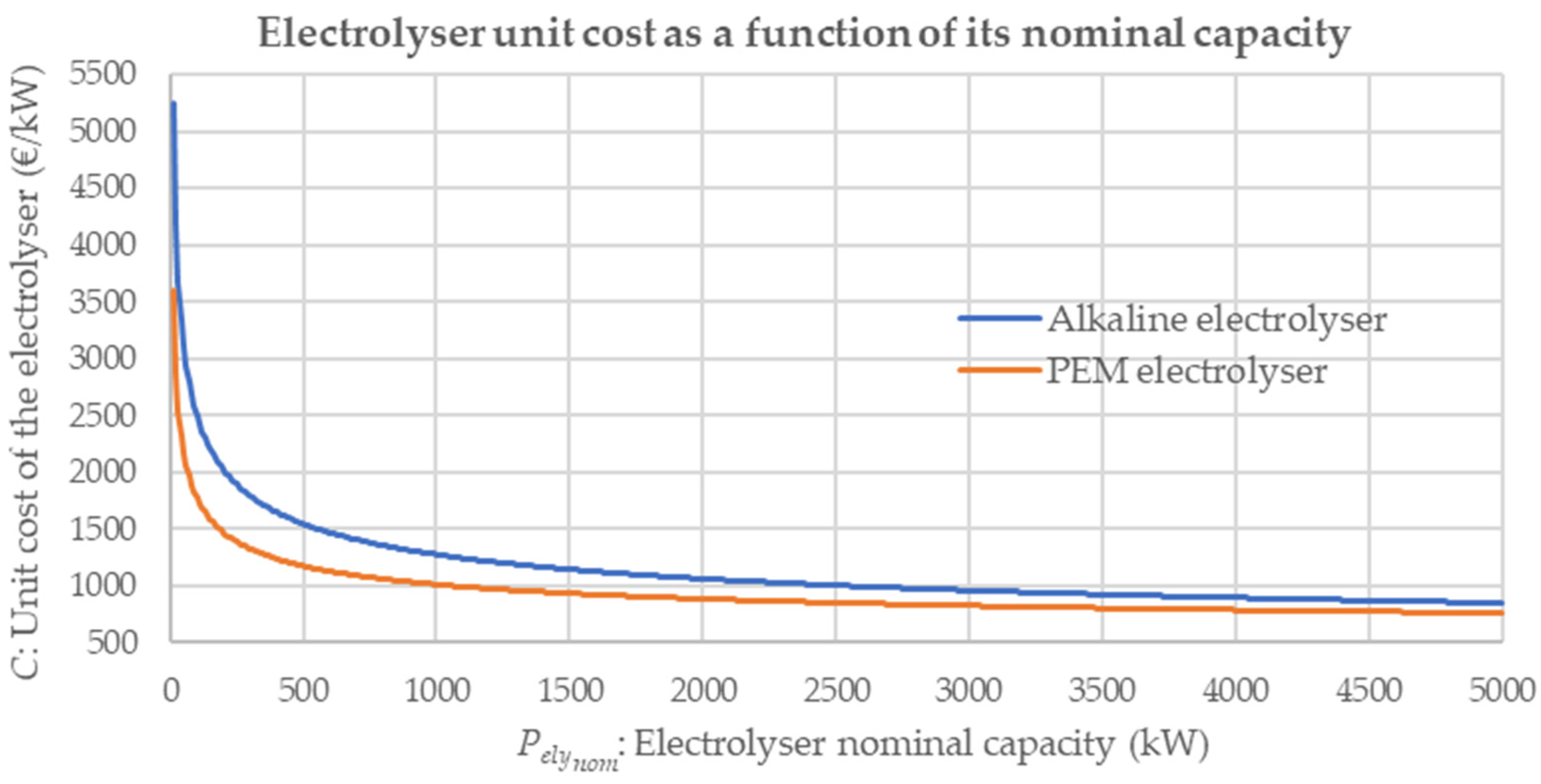

| Parameter | ALK | PEM |

|---|---|---|

| 9917.09 | 8083.93 | |

| 257.30 | 500.73 | |

| 0.649 | 0.622 | |

| −27.33 | −158.9 |

| Configuration 1 | Configuration 2 | Configuration 3 | Configuration 4 | Configuration 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Electrolysers | ×1—1 MW EL1 | ×2—500 kW EL1-EL2 | ×4—250 kW EL1-EL4 | ×10—100 kW EL1-EL10 | ×20—20 kW EL1-EL20 |

| Configuration 1 | Configuration 2 | Configuration 3 | Configuration 4 | Configuration 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMS 1 | EMS 2 | EMS 1 | EMS 2 | EMS 1 | EMS 2 | EMS 1 | EMS 2 | EMS 1 | EMS 2 | |

| Electrolyser 1 | 3975 h | 3975 h | 4370 h | 3580 h | 4370 h | 3171 h | 4370 h | 2655 h | 4370 h | 2629 h |

| Electrolyser 2 | 1960 h | 2750 h | 3363 h | 2752 h | 4370 h | 2639 h | 4370 h | 2411 h | ||

| Electrolyser 3 | 2228 h | 2708 h | 3804 h | 2538 h | 4370 h | 2584 h | ||||

| Electrolyser 4 | 1056 h | 2391 h | 3331 h | 2438 h | 4370 h | 2390 h | ||||

| Electrolyser 5 | 3001 h | 2579 h | 3883 h | 2186 h | ||||||

| Electrolyser 6 | 2389 h | 2567 h | 3421 h | 2392 h | ||||||

| Electrolyser 7 | 1841 h | 2690 h | 3352 h | 2665 h | ||||||

| Electrolyser 8 | 1369 h | 2581 h | 3290 h | 2553 h | ||||||

| Electrolyser 9 | 976 h | 2264 h | 3108 h | 2593 h | ||||||

| Electrolyser 10 | 592 h | 2628 h | 2781 h | 2615 h | ||||||

| Electrolyser 11 | 2453 h | 2705 h | ||||||||

| Electrolyser 12 | 2179 h | 2594 h | ||||||||

| Electrolyser 13 | 1904 h | 2532 h | ||||||||

| Electrolyser 14 | 1648 h | 2549 h | ||||||||

| Electrolyser 15 | 1423 h | 2471 h | ||||||||

| Electrolyser 16 | 1214 h | 2639 h | ||||||||

| Electrolyser 17 | 1019 h | 2580 h | ||||||||

| Electrolyser 18 | 786 h | 2608 h | ||||||||

| Electrolyser 19 | 619 h | 2646 h | ||||||||

| Electrolyser 20 | 451 h | 2669 h | ||||||||

| Configuration 1 | Configuration 2 | Configuration 3 | Configuration 4 | Configuration 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMS 1 | EMS 2 | EMS 1 | EMS 2 | EMS 1 | EMS 2 | EMS 1 | EMS 2 | EMS 1 | EMS 2 | |

| Electrolyser 1 | 4370 h | 4370 h | 4370 h | 3763 h | 4370 h | 3300 h | 4370 h | 2710 h | 4370 h | 2665 h |

| Electrolyser 2 | 2359 h | 2966 h | 3420 h | 2868 h | 4370 h | 2698 h | 4370 h | 2441 h | ||

| Electrolyser 3 | 2430 h | 2777 h | 3939 h | 2602 h | 4370 h | 2611 h | ||||

| Electrolyser 4 | 1206 h | 2486 h | 3358 h | 2593 h | 4370 h | 2437 h | ||||

| Electrolyser 5 | 3141 h | 2683 h | 3963 h | 2214 h | ||||||

| Electrolyser 6 | 2489 h | 2610 h | 3435 h | 2395 h | ||||||

| Electrolyser 7 | 1932 h | 2715 h | 3360 h | 2676 h | ||||||

| Electrolyser 8 | 1450 h | 2623 h | 3292 h | 2572 h | ||||||

| Electrolyser 9 | 1040 h | 2333 h | 3155 h | 2617 h | ||||||

| Electrolyser 10 | 636 h | 2670 h | 2824 h | 2638 h | ||||||

| Electrolyser 11 | 2507 h | 2728 h | ||||||||

| Electrolyser 12 | 2216 h | 2610 h | ||||||||

| Electrolyser 13 | 1947 h | 2556 h | ||||||||

| Electrolyser 14 | 1683 h | 2633 h | ||||||||

| Electrolyser 15 | 1456 h | 2496 h | ||||||||

| Electrolyser 16 | 1240 h | 2661 h | ||||||||

| Electrolyser 17 | 1046 h | 2616 h | ||||||||

| Electrolyser 18 | 818 h | 2624 h | ||||||||

| Electrolyser 19 | 645 h | 2654 h | ||||||||

| Electrolyser 20 | 476 h | 2699 h | ||||||||

| Electrolyser | Alkaline Electrolyser | PEM Electrolyser |

|---|---|---|

| Lifespan (hours) | <90,000 [39,40] | <20,000 [39] |

| 55,000–96,000 [36] | 60,000 [35] | |

| 60,000 [41] | <60,000 [40] | |

| 10,000 [42] | 60,000–100,000 [36] | |

| 20,000–60,000 [43] | ||

| 50,000–80,000 [41] |

| Electrolyser Lifespan | Electrolyser | Replacement Frequency (Years) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configuration 1 | Configuration 2 | Configuration 3 | Configuration 4 | Configuration 5 | |||||||

| EMS 1 | EMS 2 | EMS 1 | EMS 2 | EMS 1 | EMS 2 | EMS 1 | EMS 2 | EMS 1 | EMS 2 | ||

| 10,000 h | 1 | 2.27 | 2.06 | 2.51 | 2.06 | 2.84 | 2.06 | 3.38 | 2.06 | 3.42 | |

| 2 | 4.59 | 3.28 | 2.67 | 3.27 | 2.06 | 3.40 | 2.06 | 3.74 | |||

| 3 | 4.04 | 3.32 | 2.37 | 3.55 | 2.06 | 3.48 | |||||

| 4 | 8.51 | 3.76 | 2.70 | 3.69 | 2.06 | 3.76 | |||||

| 5 | 3.00 | 3.49 | 2.32 | 4.11 | |||||||

| 6 | 3.76 | 3.51 | 2.63 | 3.76 | |||||||

| 7 | 4.89 | 3.35 | 2.68 | 3.38 | |||||||

| 8 | 6.57 | 3.48 | 2.74 | 3.53 | |||||||

| 9 | 9.23 | 3.98 | 2.90 | 3.47 | |||||||

| 10 | 15.20 | 3.43 | 3.24 | 3.44 | |||||||

| 11 | 3.67 | 3.33 | |||||||||

| 12 | 4.13 | 3.47 | |||||||||

| 13 | 4.73 | 3.56 | |||||||||

| 14 | 5.45 | 3.53 | |||||||||

| 15 | 6.33 | 3.65 | |||||||||

| 16 | 7.42 | 3.41 | |||||||||

| 17 | 8.83 | 3.49 | |||||||||

| 18 | 11.45 | 3.45 | |||||||||

| 19 | 14.54 | 3.40 | |||||||||

| 20 | 19.95 | 3.38 | |||||||||

| 40,000 h | 1 | 9.05 | 8.24 | 10.05 | 8.24 | 11.35 | 8.24 | 13.56 | 8.24 | 13.69 | |

| 2 | 18.37 | 13.10 | 10.70 | 13.08 | 8.24 | 13.64 | 8.24 | 14.93 | |||

| 3 | 16.16 | 13.29 | 9.47 | 14.18 | 8.24 | 13.93 | |||||

| 4 | >25 | 15.05 | 10.80 | 14.77 | 8.24 | 15.07 | |||||

| 5 | 12.00 | 13.96 | 9.27 | 16.47 | |||||||

| 6 | 15.07 | 14.02 | 10.52 | 15.05 | |||||||

| 7 | 19.56 | 13.38 | 10.74 | 13.51 | |||||||

| 8 | >25 | 13.95 | 10.94 | 14.10 | |||||||

| 9 | >25 | 15.90 | 11.58 | 13.89 | |||||||

| 10 | >25 | 13.70 | 12.94 | 13.77 | |||||||

| 11 | 14.68 | 13.31 | |||||||||

| 12 | 16.52 | 13.88 | |||||||||

| 13 | 18.90 | 14.22 | |||||||||

| 14 | 21.84 | 14.12 | |||||||||

| 15 | >25 | 14.56 | |||||||||

| 16 | >25 | 13.64 | |||||||||

| 17 | >25 | 13.95 | |||||||||

| 18 | >25 | 13.80 | |||||||||

| 19 | >25 | 13.61 | |||||||||

| 20 | >25 | 13.49 | |||||||||

| 70,000 h | 1 | 15.85 | 14.42 | 17.60 | 14.42 | 19.86 | 14.42 | >25 | 16.02 | >25 | |

| 2 | >25 | >25 | 20.81 | >25 | 14.42 | >25 | 14.42 | >25 | |||

| 3 | >25 | >25 | 16.56 | >25 | 14.42 | >25 | |||||

| 4 | >25 | >25 | 18.91 | >25 | 14.42 | >25 | |||||

| 5 | 23.32 | >25 | 16.23 | >25 | |||||||

| 6 | >25 | >25 | 18.41 | >25 | |||||||

| 7 | >25 | >25 | 18.79 | >25 | |||||||

| 8 | >25 | >25 | 19.15 | >25 | |||||||

| 9 | >25 | >25 | 20.27 | >25 | |||||||

| 10 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | |||||||

| 11 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 12 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 13 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 14 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 15 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 16 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 17 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 18 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 19 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 20 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 100,000 h | 1 | >25 | 20.59 | >25 | 20.59 | >25 | 20.59 | >25 | 20.59 | >25 | |

| 2 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | 22.88 | >25 | 20.59 | >25 | |||

| 3 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | 20.59 | >25 | |||||

| 4 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | 20.59 | >25 | |||||

| 5 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | |||||||

| 6 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | |||||||

| 7 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | |||||||

| 8 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | |||||||

| 9 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | |||||||

| 10 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | |||||||

| 11 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 12 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 13 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 14 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 15 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 16 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 17 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 18 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 19 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 20 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| Electrolyser Lifespan | Electrolyser | Replacement Frequency (Years) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configuration 1 | Configuration 2 | Configuration 3 | Configuration 4 | Configuration 5 | |||||||

| EMS 1 | EMS 2 | EMS 1 | EMS 2 | EMS 1 | EMS 2 | EMS 1 | EMS 2 | EMS 1 | EMS 2 | ||

| 10,000 h | 1 | 2.06 | 2.06 | 2.39 | 2.06 | 2.73 | 2.06 | 3.32 | 2.06 | 3.38 | |

| 2 | 3.82 | 3.03 | 2.63 | 3.14 | 2.06 | 3.34 | 2.06 | 3.69 | |||

| 3 | 3.71 | 3.24 | 2.29 | 3.46 | 2.06 | 3.45 | |||||

| 4 | 7.46 | 3.62 | 2.68 | 3.47 | 2.06 | 3.69 | |||||

| 5 | 2.86 | 3.36 | 2.27 | 4.07 | |||||||

| 6 | 3.62 | 3.45 | 2.62 | 3.76 | |||||||

| 7 | 4.66 | 3.31 | 2.68 | 3.37 | |||||||

| 8 | 6.21 | 3.43 | 2.74 | 3.50 | |||||||

| 9 | 8.66 | 3.86 | 2.85 | 3.44 | |||||||

| 10 | 14.15 | 3.38 | 3.19 | 3.41 | |||||||

| 11 | 3.59 | 3.30 | |||||||||

| 12 | 4.06 | 3.45 | |||||||||

| 13 | 4.63 | 3.52 | |||||||||

| 14 | 5.35 | 3.41 | |||||||||

| 15 | 6.18 | 3.61 | |||||||||

| 16 | 7.25 | 3.38 | |||||||||

| 17 | 8.60 | 3.44 | |||||||||

| 18 | 11.00 | 3.43 | |||||||||

| 19 | 13.95 | 3.39 | |||||||||

| 20 | 18.90 | 3.34 | |||||||||

| 40,000 h | 1 | 8.24 | 8.24 | 9.57 | 8.24 | 10.91 | 8.24 | 13.28 | 8.24 | 13.51 | |

| 2 | 15.26 | 12.14 | 10.53 | 12.56 | 8.24 | 13.35 | 8.24 | 14.75 | |||

| 3 | 14.81 | 12.96 | 9.14 | 13.83 | 8.24 | 13.79 | |||||

| 4 | >25 | 14.48 | 10.72 | 13.89 | 8.24 | 14.77 | |||||

| 5 | 11.46 | 13.42 | 9.08 | 16.26 | |||||||

| 6 | 14.46 | 13.80 | 10.48 | 15.03 | |||||||

| 7 | 18.63 | 13.26 | 10.71 | 13.46 | |||||||

| 8 | >25 | 13.73 | 10.94 | 14.00 | |||||||

| 9 | >25 | 15.43 | 11.41 | 13.75 | |||||||

| 10 | >25 | 13.48 | 12.74 | 13.64 | |||||||

| 11 | 14.36 | 13.19 | |||||||||

| 12 | 16.25 | 13.80 | |||||||||

| 13 | 18.49 | 14.09 | |||||||||

| 14 | 21.39 | 13.67 | |||||||||

| 15 | >25 | 14.42 | |||||||||

| 16 | >25 | 13.53 | |||||||||

| 17 | >25 | 13.76 | |||||||||

| 18 | >25 | 13.72 | |||||||||

| 19 | >25 | 13.56 | |||||||||

| 20 | >25 | 13.34 | |||||||||

| 70,000 h | 1 | 14.42 | 14.42 | 16.74 | 14.42 | 19.09 | 16.02 | 14.42 | 14.42 | >25 | |

| 2 | >25 | 21.24 | 18.42 | 21.97 | 16.02 | 14.42 | 14.42 | >25 | |||

| 3 | >25 | >25 | 17.77 | 15.99 | 14.42 | >25 | |||||

| 4 | >25 | >25 | 20.85 | 18.77 | 14.42 | >25 | |||||

| 5 | 22.29 | 20.06 | 15.89 | >25 | |||||||

| 6 | >25 | >25 | 18.34 | >25 | |||||||

| 7 | >25 | >25 | 18.75 | >25 | |||||||

| 8 | >25 | >25 | 19.13 | >25 | |||||||

| 9 | >25 | >25 | 19.97 | >25 | |||||||

| 10 | >25 | >25 | 22.31 | >25 | |||||||

| 11 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 12 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 13 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 14 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 15 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 16 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 17 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 18 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 19 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 20 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 100,000 h | 1 | 20.59 | 20.59 | >25 | 20.59 | >25 | 20.59 | >25 | 20.59 | >25 | |

| 2 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | 20.59 | >25 | 20.59 | >25 | |||

| 3 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | 20.59 | >25 | |||||

| 4 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | 20.59 | >25 | |||||

| 5 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | |||||||

| 6 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | |||||||

| 7 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | |||||||

| 8 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | |||||||

| 9 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | |||||||

| 10 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | |||||||

| 11 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 12 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 13 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 14 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 15 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 16 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 17 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 18 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 19 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| 20 | >25 | >25 | |||||||||

| Electrolysis Technology | Configuration 1 | Configuration 2 | Configuration 3 | Configuration 4 | Configuration 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEM technology | 738,945 | 859,025 | 1,015,075 | 1,295,296 | 1,582,025 |

| Alkaline technology | 1,060,918 | 1,286,901 | 1,575,129 | 2,081,436 | 2,588,514 |

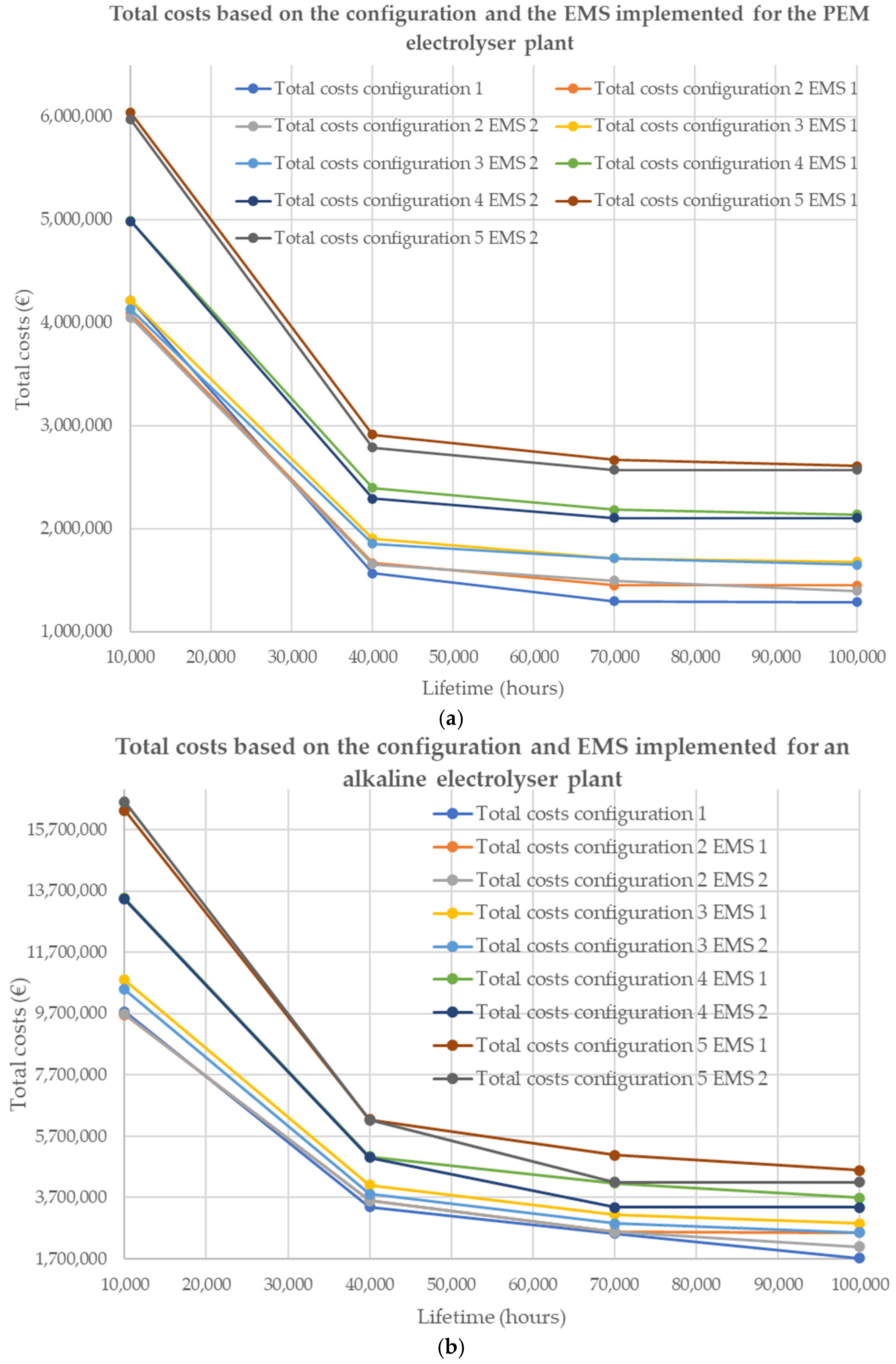

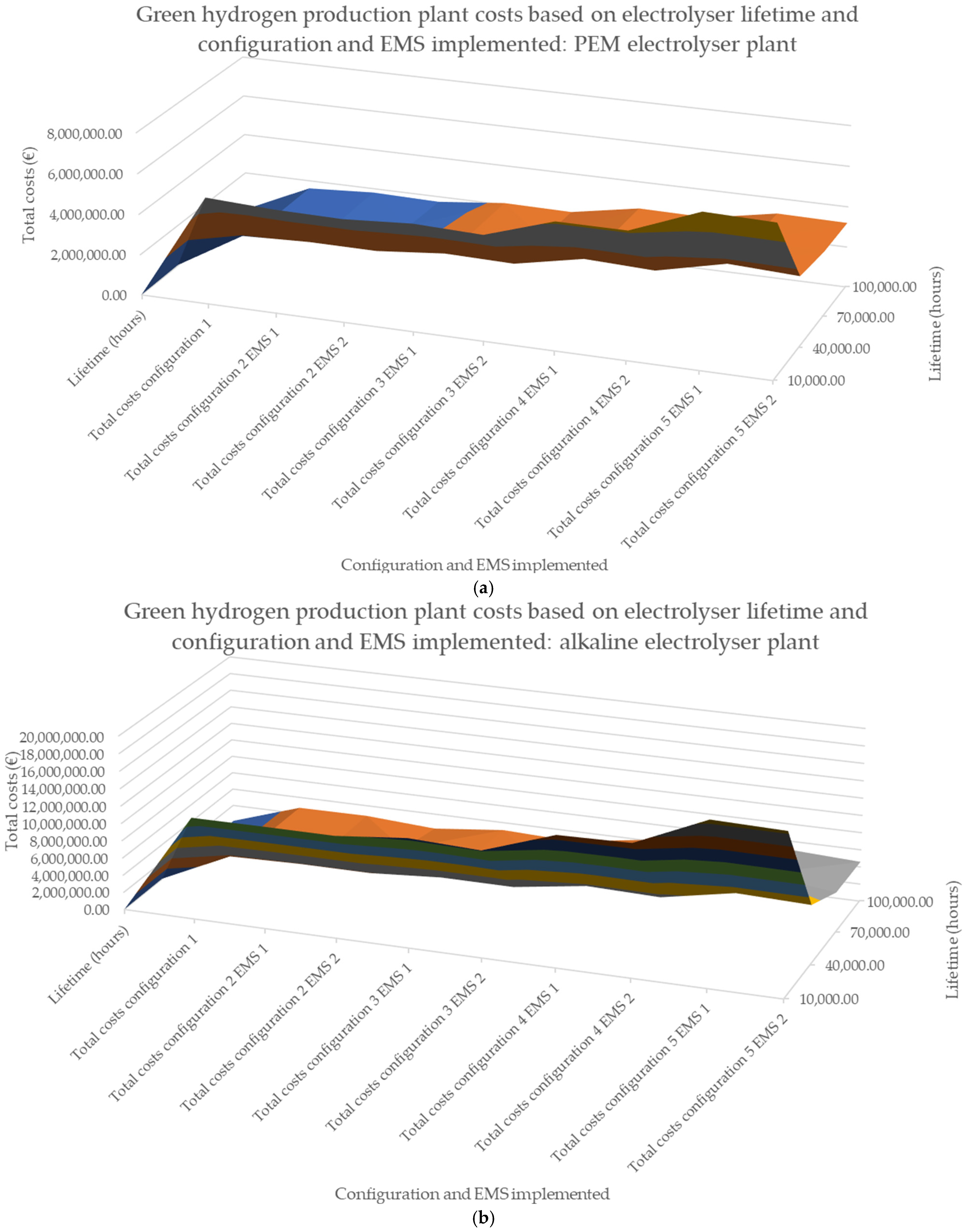

| Electrolysis Technology | Configuration 1 | Configuration 2 | Configuration 3 | Configuration 4 | Configuration 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime (Hours) | EMS 1 Costs (€) | EMS 1 Costs (€) | EMS 2 Costs (€) | EMS 1 Costs (€) | EMS 2 Costs (€) | EMS 1 Costs (€) | EMS 2 Costs (€) | EMS 1 Costs (€) | EMS 2 Costs (€) | |

| PEM | 10,000 | 3,997,853 | 3,824,289 | 3,789,161 | 3,893,251 | 3,812,789 | 4,555,977 | 4,578,695 | 5,503,463 | 5,474,112 |

| 40,000 | 1,285,285 | 1,309,534 | 1,300,850 | 1,430,719 | 1,408,605 | 1,767,435 | 1,712,473 | 2,137,577 | 2,070,613 | |

| 70,000 | 950,536 | 982,013 | 1,041,429 | 1,140,976 | 1,103,359 | 1,454,225 | 1,295,296 | 1,768,493 | 1,582,026 | |

| 100,000 | 871,662 | 936,167 | 859,026 | 1,060,652 | 1,015,075 | 1,341,824 | 1,295,296 | 1,638,853 | 1,582,026 | |

| ALK | 10,000 | 9,192,813 | 8,958,133 | 8,973,370 | 9,930,697 | 9,622,525 | 12,313,797 | 12,290,409 | 14,892,292 | 15,181,992 |

| 40,000 | 2,799,219 | 2,854,008 | 2,853,733 | 3,175,295 | 2,880,160 | 3,792,709 | 3,778,217 | 4,710,098 | 4,697,276 | |

| 70,000 | 1,905,137 | 1,805,823 | 1,785,405 | 2,193,729 | 1,868,220 | 2,890,455 | 2,081,436 | 3,499,482 | 2,588,515 | |

| 100,000 | 1,060,919 | 1,765,819 | 1,286,901 | 1,868,220 | 1,575,130 | 2,391,277 | 2,081,436 | 2,973,839 | 2,588,515 | |

| Electrolysis Technology | Configuration 1 | Configuration 2 | Configuration 3 | Configuration 4 | Configuration 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime (Hours) | EMS 1 (€) | EMS 1 (€) | EMS 2 (€) | EMS 1 (€) | EMS 2 (€) | EMS 1 (€) | EMS 2 (€) | EMS 1 (€) | EMS 2 (€) | |

| PEM | 10,000 | 221,438 | 263,818 | 263,200 | 327,188 | 318,022 | 435,149 | 408,251 | 538,610 | 500,487 |

| 40,000 | 280,134 | 357,133 | 353,931 | 473,694 | 443,864 | 626,867 | 579,257 | 775,778 | 717,284 | |

| 70,000 | 343,186 | 467,923 | 453,719 | 568,607 | 608,602 | 728,154 | 809,560 | 897,788 | 988,766 | |

| 100,000 | 416,374 | 510,463 | 536,891 | 618,808 | 634,422 | 793,620 | 809,560 | 969,298 | 988,766 | |

| ALK | 10,000 | 573,008 | 703,261 | 704,054 | 865,341 | 865,315 | 1,147,790 | 1,142,585 | 1,430,271 | 1,422,748 |

| 40,000 | 598,428 | 749,160 | 748,588 | 928,551 | 928,382 | 1,235,688 | 1,225,243 | 1,538,522 | 1,526,249 | |

| 70,000 | 619,734 | 776,294 | 782,571 | 958,096 | 976,904 | 1,270,433 | 1,300,898 | 1,581,132 | 1,617,822 | |

| 100,000 | 663,074 | 791,973 | 804,313 | 976,904 | 984,456 | 1,292,914 | 1,300,898 | 1,607,893 | 1,617,822 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rey, J.; Delgado, C.; Segura, F.; Andújar, J.M. Modularisation Analysis for Scaling Hydrogen Production: High-Power Single-Electrolyser vs. Multiple-Smaller-Electrolyser Plants. Hydrogen 2026, 7, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen7010004

Rey J, Delgado C, Segura F, Andújar JM. Modularisation Analysis for Scaling Hydrogen Production: High-Power Single-Electrolyser vs. Multiple-Smaller-Electrolyser Plants. Hydrogen. 2026; 7(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen7010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleRey, Jesús, Cirilo Delgado, Francisca Segura, and José Manuel Andújar. 2026. "Modularisation Analysis for Scaling Hydrogen Production: High-Power Single-Electrolyser vs. Multiple-Smaller-Electrolyser Plants" Hydrogen 7, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen7010004

APA StyleRey, J., Delgado, C., Segura, F., & Andújar, J. M. (2026). Modularisation Analysis for Scaling Hydrogen Production: High-Power Single-Electrolyser vs. Multiple-Smaller-Electrolyser Plants. Hydrogen, 7(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen7010004