1. Introduction

Global warming has accelerated the shift toward clean, efficient, and sustainable energy solutions [

1]. Green hydrogen (GH2) is viewed as a key enabler of Net Zero Emissions (NZEs), with projected global demand of 500–680 million tons by 2050 [

2]. Countries are increasingly integrating GH2 into industrial, mobility, and storage sectors through national strategies and roadmaps [

3]. Recent research has therefore focused on hybrid renewable energy systems for GH2 production and optimization [

4,

5].

Jordan recently announced a national GH2 strategy targeting 3.45 million tons by 2050, supported by 47 GW of renewable capacity [

6]. Leveraging the strong solar and wind resources in southern Jordan, this study uses SAM to model the site and HOMER to optimize a hybrid renewable energy system aiming to minimize LCOE and LCOH using 2030 cost assumptions. Sensitivity analyses consider electrolyzer capital cost, efficiency, lifetime, and PV and wind capital cost effects.

Globally, major GH2 importers such as South Korea (1.94 Mt), Japan (3 Mt), and the EU (20 Mt) will rely heavily on Middle East exports [

5,

7,

8,

9]. Jordan’s solar irradiation and wind corridors enable cost-competitive hydrogen production and strong export potential [

10], supporting economic opportunities and energy self-sufficiency [

11]. While GH2 planning efforts exist in developing regions (e.g., Africa), several countries still lack advanced strategic frameworks [

12,

13].

While this study focuses on Jordan, the approach of this research can be fully reproduced to utilize the hydrogen production capability of other countries and unlock their export potential, especially for developing countries. For instance, a study by the International Energy Agency (IEA) demonstrated the feasibility of hydrogen production in Africa, estimated at 5000 million tons by 2030 [

14]. Another study by the IEA projected average production in Central and South America was estimated at 5.2 million tons [

15]. Furthermore, developing countries, especially in Africa, possess an abundance of renewable resources.

This research addresses key gaps by optimizing system sizing for hybrid configurations and isolated networks. Moreover, by means of scenario analysis, recent cost projections from the IEA and IRENA are considered.

The study advances global understanding of pathways to NZE and supports the transition to hydrogen economies. Jordan’s strategic location in the Middle East—near Europe, Asia, and major shipping routes—strengthens its role as a potential green hydrogen hub for regional and international markets. The country’s proximity to energy-intensive industrial centers and global hydrogen demands positions it as a natural bridge between producers and consumers.

The manuscript is organized into four main sections following the introduction.

Section 2 provides a review of the relevant literature.

Section 3 details the methodology, including the workflow, site characteristics, and system model.

Section 4 and

Section 5 present and discuss optimization results and sensitivity analyses, with in-depth interpretation.

Section 6 concludes with the key findings and insights of the study.

2. Background

Techno-economic studies on GH2 production have evaluated system components, costs, efficiency, and dispatch using tools such as HOMER, but uncertainty remains due to varying assumptions [

10,

12]. Common evaluation metrics include LCOE, LCOH, and NPV [

16,

17].

Hybrid System Investigations:

Barakat et al. [

18]: Off-grid vs. grid-connected systems in Saudi Arabia; grid-connected systems recorded the lowest LCOH (0.505 USD/kg).

Zghaibeh et al. [

19]: Grid-connected PV–hydro in Oman; annual production of 170,939 kg at 2.25 USD/kg LCOH; electrolyzer/PV costs most influential.

Kumar et al. [

20]: Seasonal off-grid PV-biogas systems; LCOH 1.13 USD/kg with zero emissions.

Electrolyzer Variations:

Ram et al. [

21]: AWE electrolyzer used in Fiji; LCOH 9.08 USD/kg (grid) vs. 13 USD/kg (off-grid).

Tiar et al. [

22]: PEM electrolyzer implemented in Algeria; standalone PV yielded LCOH 3.7 USD/kg.

Munther et al. [

2]: Iraq; AWE was implemented with 1.98 USD/kg; PEM was implemented with 2.72 USD/kg.

Case Studies Including Storage/Hybridization:

Kumar and Karmakar [

4]: Remote Indian village; combined PV-biogas-electrolyzer-storage, achieving LCOE 0.089 USD/kWh and LCOH 3.84 USD/kg.

Jordan-Focused Studies:

Al-Mahmodi et al. [

23]: PV-CSP hybrid, with an average LCOH of 3.45 USD/kg and a minimum of 1.5 USD/kg depending on CSP/electrolyzer costs. In a complementary study [

24]: PV-wind under net metering; lowest LCOH 3.79–3.97 USD/kg.

Jaradat et al. [

25]: Southern Jordan; PV powering electrolyzer reduced LCOH from 4.42 USD/kg to 3.13 USD/kg.

Al-Ghussain et al. [

26]: Excess renewable energy; hybrid PV-wind achieved LCOH 1.082 USD/kg (2050 projections).

Shboul et al. [

27]: Economic, environmental, and policy assessment; PV-based systems achieved NPV of USD 441.95 million.

Key research gaps in the literature:

Installed capacities are often fixed rather than optimized.

2030 cost-reduction projections not fully incorporated.

Mostly single-source systems; limited hybrid configurations.

Grid-connected assumptions are common; isolated networks are rarely studied.

Little consideration for developing countries lacking infrastructure.

Lack of alignment with Jordan’s newly published GH2 strategy [

10] and the 2025 General Electricity Law promoting isolated systems [

20].

This study addresses these by the following:

Optimizing HRES sizing using HOMER with SAM-based resource modeling.

Assessing economic uncertainties via comprehensive sensitivity analyses.

Considering off-grid isolated systems relevant to emerging GH2 markets.

Leveraging 2030 cost projections consistent with IEA and IRENA.

Providing transferable insights for export-oriented GH2 strategies.

A broad literature review of previous studies focused on exploring the optimal generating mix for GH2 production is presented in

Table 1. It summarizes the key figures from both the discussed studies and additional papers that utilized the HOMER Pro software.

3. Materials and Methods

This work is based on scientific scenarios for 2030 projections from the latest global reports published by the International Energy Agency (IEA) [

15] and the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) [

54] organizations, as shown in

Table 2. These various scenarios (conservative, intermediate, and optimistic scenarios) have been used to study the impact of various variations in electrolysis technology prices. The study methodology follows a sequential two-stage approach, outlined in

Figure 1 and summarized as follows:

Phase 1: This phase identifies optimal locations for renewable energy development by analyzing site surveys that highlight areas with the highest solar radiation and wind speeds. These locations are selected using reputable online tools such as the Solar and Wind Atlas. Subsequently, the SAM software (v2025.4.16) developed by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) will be utilized, leveraging a comprehensive database of high-resolution weather data from the National Solar Radiation Database (NSRDB) website, also developed by NREL. The results of this phase will include per-unit generation curves, which serve as inputs for the next project phase.

Phase 2: This phase forms the core of this study, integrating Phase 1 results with technical, economic, and system constraints for simulation in HOMER Pro software (v3.18.4). Optimization results will then be extracted for all scenarios, with extensive sensitivity analyses on electrolyzer cost, efficiency, lifetime, and PV and wind costs to assess their impact on LCOH, LCOE, NPV, and installed capacities.

The following sections provide further details on the process of defining the location, electrical and hydrogen loads, and system components, along with their mathematical modeling and economic data.

3.1. Hydrogen Production Hub Site Selection

According to the latest government updates regarding the GH2 production in Jordan, as highlighted by the National Green Hydrogen Strategy and supported by a recent amendment to the General Electricity Law, an independent electricity grid will be established to supply GH2 projects with renewable sources. The government’s vision is to position Jordan as a regional hydrogen export hub, based on visions extending to 2030, 2040, and 2050. This will be achieved by making the Aqaba Special Economic Zone a center for this industry, given its proximity to the port of Aqaba—Jordan’s only seaport to the world—and major highways [

6,

55,

56].

Figure 2 illustrates the proposed location for a GH2 generation plant in the southwest of the Kingdom, in the Aqaba Governorate, within the Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority (ASEZA). Its proximity to the port of Aqaba significantly reduces transportation costs compared to more distant locations.

3.2. Renewable Energy Site Selection

Jordan boasts a strategic location in the Mediterranean basin, supported by an average global horizontal irradiation (GHI) of 5.5–6.4 kWh/m and approximately 300 sunny days per year, which ranks among the best in the world [

27,

57]. The highest levels of solar radiation are concentrated in the south of the Kingdom, supporting solar energy generation projects, as

Figure 3a illustrates. Additionally, the average wind speed reaches 7 m/s, which is feasible for energy generation using wind turbines, as shown in

Figure 3b, measured at a hub height of 100 m [

27,

58]. According to literature, this value is greater than the average speed of 4.5 m/s recommended for commercial production [

59]. The specific locations were chosen due to their proximity to the hydrogen production site and their potential for future expansion of electricity-generating capacity in this promising area. One advantage of using both PV and wind is to support a more stable and continuous supply, as they can compensate each other to some extent [

60].

3.3. Electric and Hydrogen Load Profiles

By the end of 2024, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR) had signed several Memoranda of Understanding (MoU) with international developers to conduct feasibility studies for GH2 production in Jordan. The targeted production quantities range between 17.7 kt and 35 kt of green hydrogen per year [

61]. This paper targets an annual GH2 consumption of 17.7 kt.

Figure 4a illustrates the hourly hydrogen consumption, scaled with a daily average of approximately 48,624 kg. Here, we assume the electrolyzer is flexible enough to adjust its hydrogen production to the variations in renewable energy supply [

62]. To model the per-unit Balance of Plant (BOP) electrical load, the ratio between electrical load and hydrogen load is 1.344 kWh/kg [

19,

63].

Figure 4b illustrates the hourly electric load, scaled to a daily average of approximately 65,352 kWh.

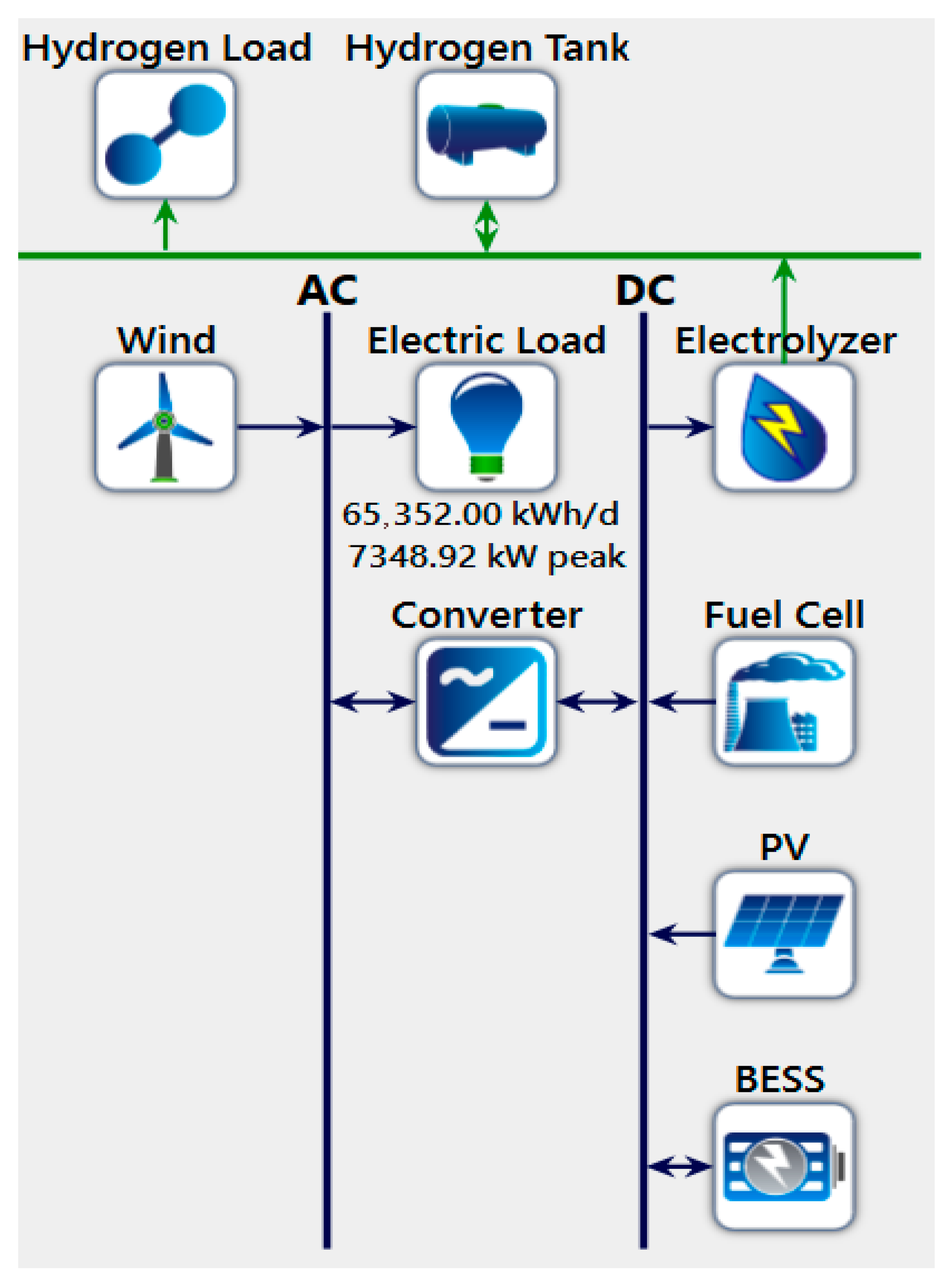

3.4. System Modeling

The proposed GH2 production system consists of several components within both the hydrogen and electrical systems. These include solar PV panels, wind turbines, and BESS that generate needed electricity. It also includes hydrogen storage units and fuel cells. Regarding the power conversion component, it is assumed to be integrated into each related subsystem. Furthermore, conversion losses are assumed to be implicitly integrated within the efficiencies of the corresponding subsystems. The goal is to supply both hydrogen and electrical loads.

Figure 5 depicts the schematic diagram of the proposed system components. The optimal combination is selected using HOMER Pro’s optimization model. The following subsections demonstrate the mathematical representation of each component, along with the technical and economic information used in this study.

3.4.1. Solar PV System

A 1 kW solar system was modeled to produce a per-unit power curve based on the selected site using the SAM’s simulation methodology after providing the necessary weather data [

63]. This curve was then applied in the HOMER optimization model to determine the optimal system size. Equation (1) describes the power output of the solar system. Equation (2) shows the effective total irradiance, while the panel temperature is shown in Equation (3).

where

is the output power of the PV module (

),

is the effective total irradiance,

is the module’s efficiency (%),

is the module’ surface Area (m

2),

is the temperature coefficient of maximum power (%/°C), and

is the operating temperature of the PV cell (°C).

where

is the effective beam (direct) irradiance (W/

),

is the effective diffuse irradiance (W/

),

is the effective diffuse irradiance reflected from the ground (W/

), and

is the diffuse irradiance utilization factor.

where

is the cell temperature (°C),

is the effective irradiance transmitted to the cell (W/

),

is the module’s Nominal Operating Cell Temperature (NOCT) rating (°C),

is the reference module efficiency (%) at 1000 W/

,

is the effective transmittance-absorptance product, and

is the wind speed (m/s).

Table 3 presents the technical parameters of the solar power plant modeled in the SAM software.

3.4.2. Wind Turbine System

Like solar plant modeling, the same process is applied to the wind farm. Weather data is input into the SAM to generate a per-unit hourly power output curve. The SAM utilizes the Weibull distribution to model the power output behavior of wind turbines [

64]. The power output is described by Equation (4). Additionally, wind speed at hub height is adjusted from the anemometer height using Equation (5).

where

is the turbine output at hub height wind speed for hour

j,

is the hub height wind speed for hour

j,

is the turbine output at wind speed

from the power curve, and

and

are the nearest lower and upper wind speeds on the power curve surrounding the hub height wind speed, respectively.

where

is the wind speed at the data height from the weather file for hour

j,

is the turbine hub height,

is the measurement height at which wind speed was recorded in the weather file closest to the hub height, and

is the wind shear coefficient.

Table 4 presents the wind power plant specifications modeled in SAM, with the generation profile normalized (per-unit) for use in the HOMER optimization model.

3.4.3. BESS Storage

Lithium-ion batteries are utilized to store excess energy from renewable power sources. Two types are considered: short-duration batteries (less than 1 h) for frequency regulation and rapid response, and longer-duration batteries (4 h) for energy shifting. Each battery type is assumed to have a capacity of 1 MW. The system is designed so that the optimizer selects the most suitable battery duration based on the modeled conditions. Equation (6) presents the calculation for the lifetime energy throughput of the battery [

34,

65].

Table 5 summarizes the default technical specifications for both battery configurations.

where

is the total lifetime throughput (kWh),

is the number of cycles until failure,

is the depth of discharge (%),

is the maximum storage capacity (Ah), and

is the nominal voltage (V).

3.4.4. Electrolyzer

The electrolyzer is the most critical component of the GH2 system. It decomposes water at its electrodes using electricity from various sources within the hybrid system. Equation (7) illustrates the chemical reaction that separates water through a specialized membrane [

66].

In this study, a generic electrolyzer type is modeled with technical characteristics presented in

Table 6 [

65]. The production quantity is calculated using Equation (8) [

31].

where

is the electrolyzer’s hydrogen production quantity in kg,

is the power consumption of the electrolyzer,

is the electrolyzer efficiency, and

is the hydrogen higher heating value.

3.4.5. Hydrogen Storage Tank

The fabricated hydrogen storage tank is used to store the hydrogen produced by the station. It is an important component that contributes to the stability of the hydrogen production system [

34,

35]. Equation (9) represents the autonomy of the hydrogen storage tank. The technical parameters of the hydrogen storage tank are stated in

Table 7.

where

is the autonomy of the hydrogen storage tank in hours,

is the hydrogen storage capacity (kg),

is the lower heating value of hydrogen (120 MJ/kg), and

is the average primary daily load (kWh/day).

3.4.6. Fuel Cell

The fuel cell is another key component modeled to convert stored hydrogen to electricity to support the system operation. Equation (10) represents the fuel cell’s power output [

53]. Technical parameters of the fuel cell are provided in

Table 8.

where

is the power generated by the fuel cell,

is the number of fuel cells in the stack,

is the fuel cell output voltage, and

is the fuel cell current.

3.4.7. Economic Parameters

After defining the technical aspects of various system components, this section explains the economic aspects of the study. Extensive and comprehensive research was conducted to determine the prices of various technologies according to the scenarios adopted in the study.

Table 9 presents the general economic data for the project.

The existing power grid infrastructure in Jordan is well-developed and is operated, maintained, and planned by the National Electric Power Company (NEPCO). Nevertheless, as previously highlighted, this study is entirely based on an assumption of using an isolated network specifically for green hydrogen production. This approach aligns with the recently published national hydrogen strategy and adheres to the provisions of the updated General Electricity Law. Accordingly, the fixed costs associated with the development of the required infrastructure were identified. These include the cost of an 80 km, 400 kV transmission line, which would otherwise be necessary to connect the hydrogen production facility to the national grid. Based on unit costs published in NEPCO’s 2017 Electricity Sector Master Plan [

67], the transmission line cost was estimated at 634,000 USD/km. In addition, the fixed costs also encompass the cost of desalinated water required for hydrogen production, estimated at 1 USD per kilogram of hydrogen produced [

68]. In total, the fixed investment cost for the system was estimated at approximately USD 60 million.

Table 10 and

Table 11 provide detailed Capital Expenditures (CAPEX), replacement costs incurred at the end of each component’s lifetime, and Operational Expenditures (OPEX) cost projections for 2030 of all system components.

The strength of HOMER Pro software lies in its ability to find the optimal solution by incorporating most technical and economic characteristics of all components of a hybrid system. This facilitates the feasibility study of such projects by calculating key performance indicators to examine the impact of changes in specific technical or economic system characteristics on these indicators. The most important indicators include the LCOE in USD/kWh, the LCOH in USD/kg, and the NPV in USD millions. The LCOE is the average cost of electricity from the system’s generation power sources.

Equation (11) describes the annual nominal discount rate

adjusted for the inflation rate of

to produce the real discount rate

[

65].

The

is calculated by dividing the sum of total discounted renewable sources costs in a year

by the sum of total discounted energy produced in a year

, as presented in Equation (12) [

24,

65].

The

represents the cost of producing one kilogram of hydrogen. The

is calculated by dividing the sum of total discounted system costs in a year

by the total discounted hydrogen produced in a year n, as presented in Equation (13) [

24,

35,

65]. It is a key performance indicator that reflects the feasibility of producing this commodity using a hybrid system.

The

represents the current equivalent value of all future cash flows associated with a project after discounting them to reflect the time value of money. It provides a unified measure of the project’s economic performance by converting all future financial impacts into their present-day value. It is calculated by the sum of total discounted system costs in a year

as presented in Equation (14) [

24,

65].

3.5. Sensitivity Variations

Sensitivity variations to the base case input parameters are applied.

Table 12 demonstrates the sensitivity mapping for all indicators applied to the defined scenarios in

Table 2. This sensitivity analysis provides a comprehensive insight into the effect of each parameter on the resulting indicators. Base case values not associated with a visualized sensitivity case are considered fixed.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents a variety of technical and economic optimization results according to various sensitivity variations. Economic results include LCOH, LCOE, and NPV, while technical results include the installed sizes of the optimal components, such as PV, wind turbines, electrolyzers, hydrogen storage tanks, and fuel cells. It is important to note that BESS was not selected as part of the feasible optimized components due to its technical and economic limitations as compared to other supporting components.

HOMER performs an hourly time-series simulation in which renewable electricity generation is first allocated to meet the system’s electrical demand, including balance-of-plant loads. Any surplus electricity is then directed to electrolyzer operation for hydrogen production, subject to component capacity constraints. Hydrogen is stored when excess renewable energy is available, while electrolyzer operation is reduced during periods of limited resource availability. The reported annual performance indicators and cost metrics are obtained by aggregating this hourly operational behavior over the full simulation year.

It is important to note that the future cost assumptions adopted in this study are subject to inherent uncertainty, as long-term projections depend on technological progress, market dynamics, and policy developments. Therefore, the analyzed scenarios should be interpreted as indicative trends rather than precise predictions. The sensitivity analysis is employed to capture the relative influence of key cost parameters on system performance and costs, providing insight into the robustness of the optimized configurations under plausible future cost variations.

4.1. Economic Indicators

The primary economic metrics considered in this study are LCOH, LCOE, and NPV; these indicators are widely used to evaluate the economic feasibility of GH2 production [

21,

34]. The following sections illustrate how these indicators change under different scenarios and sensitivities.

4.1.1. LCOH Results

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 present contour maps that illustrate how the LCOH varies across the five scenarios and under each sensitivity case. The results indicate a wide range of LCOH (1.59–3.49 USD/kg).

Figure 6 visualizes the effect of changing electrolyzer capital cost on LCOH. The lowest value is 1.59 USD/kg in the IRENA optimistic scenario SC2, with a cost variation factor of 0.5, while the highest value recorded is 3.49 USD/kg in the IEA conservative scenario SC1, with a cost variation factor of 1.5. Varying electrolyzer costs produced a wide range of values, demonstrating how reducing technology costs can significantly reduce the cost of the produced commodity. For variations in electrolyzer efficiency, as shown in

Figure 7, LCOH values remain steady within a single scenario. The lowest value is 1.77 USD/kg in IRENA SC2 at the highest efficiency, while the highest is 3.14 USD/kg measured at a lower efficiency of 67% for the pessimistic scenario, IEA SC1. Similar behavior results for lifetime variations, as shown in

Figure 8. The range slightly changes within one scenario, with values of 3.08 USD/kg in SC1 for a lifetime of 15 years and 1.8 USD/kg for IRENA SC2 at 20 years of lifetime. Therefore, varying electrolyzer efficiency and lifetime have less effect compared to capital cost variations.

The effect of PV and wind capital cost variations on LCOH is shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, respectively. Capital variations produced wide LCOH changes in both cases. For PV capital variations, the range is between 1.67 USD/kg and 3.26 USD/kg for IRENA SC2 with a cost factor of 0.5 and IEA SC1 with a cost factor of 1.5, respectively. Similarly, for wind capital cost variations, the range is between 1.69 USD/kg and 3.17 USD/kg for IRENA SC2 with a cost factor of 0.5 and IEA SC1 with a cost factor of 1.5, respectively.

4.1.2. LCOE Results

Another important indicator is the cost of electricity produced from renewable energy sources in USD/kWh across various scenarios and sensitivity cases. The results indicate a wide range of LCOE (0.0072–0.0301 USD/kWh).

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 depict the resulting LCOE and its change when certain system parameters vary.

Figure 11 illustrates that the LCOE ranges from 0.01 USD/kWh for IRENA SC2 at most of the electrolyzer’s cost factors to 0.025 USD/kWh in IRENA SC1 with a cost factor of 1.5. Similarly, variations in electrolyzer efficiency and lifetime are shown in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13, respectively. The recorded ranges are 0.01 USD/kWh–0.0203 USD/kWh and 0.01 USD/kWh–0.024 USD/kWh for changes in electrolyzer efficiency and lifetime, respectively. It is clearly shown that changing the electrolyzer efficiency and lifetime does not significantly affect LCOE, as values remain steady within each scenario across these variations.

Additional exploration shows that changing PV and wind capital leads to observable deviations in the resulting prices. PV capital variations produced the lowest LCOE of 0.0072 USD/kWh for IEA SC2 and SC3 at a factor of 0.5 and the highest for IRENA SC1 with a factor of 1.5, as shown in

Figure 14. Furthermore, considering wind capital variations produces clear LCOE changes between 0.01 USD/kWh for the IRENA SC2 base case factor and afterwards and 0.0233 USD/kWh for IRENA SC1 at a 0.9 factor, as presented in

Figure 15. LCOE is sensitive to PV and wind capital changes as a response to variations in the total amount of energy and capital present values, showing a different impact compared to electrolyzer parameter variations.

4.1.3. NPV Results

The discounted total system costs over the project lifetime are shown in

Figure 16,

Figure 17,

Figure 18,

Figure 19 and

Figure 20, highlighting various changes over scenarios and sensitivities.

Figure 16 presents how NPV increases with rising electrolyzer capital costs. The highest value is observed for the conservative scenario IEA SC1, followed by the conservative IRENA SC2 scenario across all variations. The lowest value is USD 427 million at a 0.5 cost factor, while the highest is USD 928 million at a 1.5 cost factor. Similarly, increasing electrolyzer efficiency from 67 to 69% slightly reduces NPV across a single scenario with values ranging from USD 471.6 million to USD 832.1 million, as presented in

Figure 17. Furthermore, extending electrolyzer lifetime from 15 to 20 years also causes a minor decrease in NPV within a single scenario, with values spanning USD 481 million to USD 834.6 million, as seen in

Figure 18. Additional observations are illustrated by

Figure 19 and

Figure 20, showing the effects of PV and wind capital changes, respectively. Increasing PV capital over a factor ranging from 0.5 to 1.5 leads to a rise in NPV, with a minimum value of USD 443.2 million in IRENA SC2 and a maximum of USD 865.8 million in IEA SC1. Similarly, increasing wind capital results in NPVs ranging from USD 447.7 million in the optimistic scenario IRENA SC1 to USD 844.4 million in the conservative scenario IEA SC1. In the case of increasing PV capital, the optimizer tends to install more wind turbines, and vice versa when wind capital costs rise. Therefore, only slight changes in NPVs are observed at higher sensitivity factors.

4.2. Technical Indicators

In this section, the technical optimization results will be presented, which include the optimal generation mix of renewable sources, electrolyzer capacity, fuel cell capacity, and hydrogen storage tank size.

4.2.1. PV, Wind, Electrolyzer Optimized Capacities

Figure 21,

Figure 22,

Figure 23,

Figure 24 and

Figure 25 provide comprehensive aggregated insights into the optimized capacities of PV, wind, and electrolyzers in MW across scenarios and sensitivity cases. In the case of increasing electrolyzer capital costs with variation factors between 0.5 and 1.5, PV installations decrease across IEA scenarios, while similar installation levels are observed in IRENA scenarios, as shown in

Figure 21. PV installed capacities range from 211 MW to 403 MW. On the other hand, wind installations are slightly affected by electrolyzer cost variations, with a maximum capacity of 215 MW, and no installations in most variations in the IRENA scenarios. Electrolyzer capacities also decrease, with values ranging from 203 MW to 336 MW.

Electrolyzer efficiency and lifetime variations across a single scenario show less impact than capital cost changes.

Figure 22 and

Figure 23 illustrate that PV installations vary slightly, with ranges of 203.8 MW to 382.5 MW for efficiency variations and 211 MW to 403.7 MW for lifetime variations. Similarly, wind capacities show limited variation, except for IRENA scenarios where no wind installations occur in most sensitivity cases. The maximum wind capacity installed is 219 MW for efficiency variations and 215 MW for lifetime variations. Electrolyzer capacities also remain relatively stable, ranging between 192.4 MW and 339.2 MW for efficiency change, and between 209.5 MW and 335.4 MW for lifetime variation.

Further insights are provided through PV and wind capital cost sensitivities, as shown in

Figure 24 and

Figure 25, respectively.

Figure 24 depicts that increasing PV capital costs results in a reduction in PV capacities, ranging between 203.8 MW and 382.5 MW. However, in IRENA SC2, where no wind is installed, the optimizer compensates with higher PV installations. Electrolyzer installation values strongly influence PV sizing, with a capacity range from 192.4 MW to 345.9 MW. On the other hand, wind installations remain mostly unchanged, again with the exception of IRENA scenarios.

Figure 25 reveals the effect of wind capital cost variation on installed capacities. As wind costs increase, the installed wind capacity decreases, with a maximum of 215 MW. In contrast, PV and electrolyzer installations increase, with PV ranging from 217 MW to 406 MW, and electrolyzers ranging from 216 MW to 335 MW. This clearly indicates that the optimizer shifts preference to PV and electrolyzer as wind becomes more expensive, which means a less feasible energy source.

4.2.2. Fuel Cell and Hydrogen Storage Optimized Capacities

Further technical insights can be obtained regarding the optimized sizes of the fuel cell and hydrogen storage tank.

Figure 26,

Figure 27,

Figure 28,

Figure 29 and

Figure 30 provide a combined visualization of these capacities across scenarios and under various sensitivity variations from the base case. Fuel cell sizes are shown as cumulative line curves to better illustrate trends, while hydrogen storage tank sizes are demonstrated by bar charts. For electrolyzer capital cost variations,

Figure 26 shows that hydrogen storage sizes decrease with a range of 30–50 tons as costs increase. Similarly, fuel cell capacities tend to decrease from a maximum of 2900 kW to 500 kW with similar trends over different scenarios. However, in IRENA scenarios, the fuel cell capacity remains nearly constant, indicating a minimum required size that is not sensitive to capital cost variations.

In contrast, variations in electrolyzer efficiency and lifetime lead to increased installations, as shown in

Figure 27 and

Figure 28. Across these sensitivities, hydrogen storage tank sizes grow from 30 tons to 50 tons, while fuel cell capacities increase from 500 kW to 2500 kW. IRENA SC1 and SC2 remain mostly unaffected by the mentioned variations. Further exploration of PV and wind cost variations is also provided.

Figure 29 depicts that with increasing PV costs, the fuel cell capacity declines from 2900 kW to 500 kW, and the hydrogen storage tank size reduces from 50 to 30 tons, except in IRENA scenarios, where minimum sizes are consistently optimized. Regarding wind variations,

Figure 30 reveals a contrasting behavior. As wind capital costs increase, fuel cell capacities increase from 500 kW to 2700 kW, and hydrogen storage tank sizes range from 30 to 50 tons. This pattern reflects the system’s increased reliance on fuel cells and hydrogen storage support when high PV installations are optimized to compensate for reduced wind installations under higher wind cost conditions.

5. Discussion

A comparative evaluation with previous HRES-based hydrogen studies listed in

Table 1 highlights the techno-economic competitiveness of the present work, especially in terms of both LCOE and LCOH. The obtained LCOE in this study (0.0072–0.0301 USD/kWh) lies within the lower range of values reported in the recent literature under comparable off-grid and high-resource conditions, and should be interpreted in the context of Jordan’s favorable renewable resource availability and system scale. For example, Australia’s isolated microgrid system [

48] achieved 0.35 USD/kWh, while Turkey’s residential system [

42] reports an even higher value of 0.376 USD/kWh. India’s hydrogen-fueled bus system [

4] yielded 0.087 USD/kWh, and Pakistan’s university microgrid [

30] reached 0.1084 USD/kWh, all of which are noticeably above the present outcome but reflect different system scales, demand profiles, and regional constraints. Similarly, the island electrification system in South Korea [

44] had an LCOE of 0.366 USD/kWh, emphasizing the impact of high intermittency and limited resource availability. Even the Czech Republic’s refueling system [

35] reported 0.3 USD/kWh, highlighting how application-specific requirements and infrastructure constraints influence cost outcomes. These comparisons indicate that optimized component sizing combined with strong solar and wind resources can lead to highly competitive LCOE values under suitable conditions, rather than implying absolute superiority.

In terms of hydrogen production cost, the present work (1.59–3.49 USD/kg) also demonstrates competitive performance relative to most existing research within similar production-oriented configurations. For example, Mexico’s oil-refinery-oriented design [

29] reached 4.2 USD/kg, while the refueling station study in Australia [

50] achieved 5.79 USD/kg. Refueling applications in Sweden [

46] yielded 5.18 USD/kg, and the industrial hydrogen system in Iran [

38] reported 3.94 USD/kg, all exceeding the upper limit of the current study. Even large commercial-scale work in Saudi Arabia [

16] reached 5.26 USD/kg due to partial reliance on grid purchasing, whereas the proposed system here benefits from a fully off-grid renewable supply. In contrast, highly localized micro applications such as Pakistan’s small off-grid design [

20] reported 1.13–1.18 USD/kg, which is lower than the present results but achieved at a substantially smaller system scale and with different operational objectives, making such comparisons scenario-dependent rather than directly comparable.

The relatively lower LCOE values obtained in this study may be primarily attributed to the synergistic interaction between solar and wind resources in Jordan, combined with optimized electrolyzer sizing and improved load-matching. Several reviewed works report higher LCOE values due to single-resource dependency, constrained resource quality, or suboptimal system configurations. For instance, the hybrid microgrid in Turkey [

31,

32] operates under relatively weaker solar irradiance patterns, driving an LCOE of 0.327 USD/kWh, while the residential-scale systems in Chad [

39] and Australia [

33] demonstrated strong technical feasibility but lacked large-scale electrolytic hydrogen output, limiting cost competitiveness. Additionally, reliance on partial grid imports in the Saudi and Pakistan studies [

16,

30] led to elevated energy costs due to fluctuating tariff structures. Conversely, the fully autonomous approach adopted here mitigates tariff volatility entirely, converting all renewable surplus into hydrogen storage and thereby minimizing curtailment and reducing the effective energy cost. By comparison, several off-grid systems in Africa [

30] and South Korea [

44] experience intermittency challenges due to the absence of optimized hydrogen storage integration, which highlights the importance of coordinated system design in improving overall techno-economic performance.

Beyond cost comparison, the application scale, regional environment, and system objectives play a crucial role in interpreting the deviations between this study and the referenced literature. For example, the studies targeting hydrogen refueling stations (e.g., Sweden [

46], Italy [

43], and Australia [

50]) emphasize reliability constraints and infrastructure redundancy, naturally increasing their LCOH values. Industrial supply cases such as those in Iran [

38] and Mexico [

29] are driven by refinery-grade quality specifications and chemical process integration, demanding additional conditioning equipment that raises cost. In contrast, this study focuses on scalable, large-scale production oriented toward export-capable green hydrogen applications, benefiting from reduced purification requirements due to optimized electrolyzer selection. Furthermore, MENA-region works, such as Morocco [

41] and Oman [

19,

49], demonstrate techno-economic viability under high solar irradiance; however, the costs remain higher due to limited hybridization between solar and wind resources, the absence of advanced dispatch strategies, or grid dependency.

The results presented here, therefore, extend the regional literature by demonstrating that hybrid multi-resource operation combined with optimized storage and component sizing can significantly enhance cost competitiveness, even in fully off-grid mode. Accordingly, the present results should be viewed as context-specific evidence of competitiveness under hybrid, off-grid, multi-resource conditions rather than as universally superior benchmarks.

Overall, these comparative findings demonstrate that the proposed hybrid system yields competitive techno-economic outcomes under the defined technical, economic, and geographic assumptions, confirming its feasibility and positioning it as a promising candidate for large-scale green hydrogen development within similar high-resource and off-grid contexts.

6. Conclusions

This study presents a techno-economic assessment of an optimized hybrid renewable energy system for green hydrogen production in Jordan. Using HOMER Pro software, the optimal sizing of PV, wind, electrolyzers, hydrogen storage, fuel cells, and BESS was determined, while SAM software was employed to evaluate renewable resource potential at the selected site. Technology cost projections for 2030 were drawn from IEA and IRENA reports. Extensive sensitivity analyses examined the influence of electrolyzer cost, efficiency, and lifetime, along with PV and wind capital costs, on both technical and economic performance.

The results revealed high sensitivity of installed capacities to scenarios and parameters. PV ranged from 203 to 457 MW, wind between 0 and 220 MW, and electrolyzers spanned from 192.4 to 346.5 MW. Fuel cells and hydrogen storage were optimized at 500–3000 kW and 30–50 tons, respectively. BESS was excluded from all optimal configurations, as fuel cells and hydrogen tanks sufficiently met short-term hydrogen and electricity demands.

Economically, the LCOH demonstrated a promising range across different sensitivity cases. It ranged from 1.59 USD/kg in IRENA SC2 with a 50% electrolyzer cost reduction to 3.49 USD/kg in IEA SC1 under the same conditions. The LCOE varied between 0.0072 USD/kWh in IEA SC2 and SC3 at a 0.5 PV cost factor and 0.0301 USD/kWh when PV cost increased by a 1.5 factor at IRENA SC1. NPV spanned from USD 447.69 million in IRENA SC2 at a 0.5 wind cost factor to USD 927.59 million in IEA SC1 with a 1.5 electrolyzer cost factor. Overall, capital cost variations had a greater impact on techno-economic outcomes than electrolyzer efficiency or lifetime.

This study plays a vital role in demonstrating the techno-economic feasibility of GH2 production in Jordan. It also delivers actionable insights for worldwide policymakers, investors, and researchers engaged in clean energy development. The relevance of the findings is further reinforced by their alignment with the strategic goals outlined in various international green hydrogen strategies. Furthermore, the findings serve as a robust, reproducible work reference for other countries aiming to develop large-scale green hydrogen projects and strategies tailored to local climatic and geographic conditions, supporting informed, context-sensitive energy planning.

While this study provides valuable insights into the techno-economic feasibility of off-grid green hydrogen production, several model simplifications should be acknowledged. The analysis focuses on annual performance indicators using deterministic inputs and a generic electrolyzer representation, without explicitly modeling grid constraints, stochastic resource variability, or downstream hydrogen conversion pathways. Future research should extend the current framework to assess the feasibility of green ammonia production as an export-oriented energy carrier, conduct detailed grid integration and stability studies, and incorporate advanced optimization tools beyond HOMER that enable multi-year dispatch and transmission modeling. In addition, uncertainty and risk-based analyses considering renewable variability and policy dynamics would further enhance the robustness of large-scale green hydrogen assessments. Expanding the scope to regional integration, export markets, and regulatory frameworks would support strategic planning for Jordan’s green hydrogen ambitions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. (Ahmad Abuyahya); methodology, A.A. (Ahmad Abuyahya); software, A.A. (Ahmad Abuyahya); validation, A.A. (Ahmad Abuyahya), E.A.F., and A.A. (Anas Abuzayed); formal analysis, A.A. (Ahmad Abuyahya); investigation, A.A. (Ahmad Abuyahya), E.A.F., and A.A. (Anas Abuzayed); resources, E.A.F. and A.A. (Anas Abuzayed); data curation, A.A. (Ahmad Abuyahya); writing—original draft preparation, A.A. (Ahmad Abuyahya); writing—review and editing, A.A. (Ahmad Abuyahya), E.A.F., and A.A. (Anas Abuzayed); visualization, A.A. (Ahmad Abuyahya); supervision, E.A.F.; project administration, E.A.F.; funding acquisition, A.A. (Anas Abuzayed). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All input data, HOMER and SAM simulation files, and results are available upon request from the first author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the University of Jordan for its support and facilitation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASEZA | Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority |

| AWE | Alkaline Water Electrolyzer |

| BESS | Battery Energy Storage System |

| BOP | Balance of Plant |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditures |

| CPEC | China–Pakistan Economic Corridor |

| CSP | Concentrated Solar Power |

| FCEVs | Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles |

| GH2 | Green Hydrogen |

| GHI | Global horizontal irradiation |

| HOMER | Hybrid Optimization Model for Electric Renewables |

| HRES | Hybrid renewable energy system |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| IRENA | International Renewable Energy Agency |

| LCOE | Levelized Cost of Energy |

| LCOH | Levelized Cost of Hydrogen |

| MEMR | Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources |

| MoU | Memoranda of Understanding |

| NEPCO | National Electric Power Company |

| NOCT | Nominal Operating Cell Temperature |

| NPV | Net Present Value |

| NREL | National Renewable Energy Laboratory |

| NSRDB | National Solar Radiation Database |

| NZEs | Net Zero Emissions |

| OPEX | Operational Expenditures |

| PEM | Proton Exchange Membrane |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| TES | Thermal Energy Storage |

References

- Zia, M.F.; Elbouchikhi, E.; Benbouzid, M. Microgrids energy management systems: A critical review on methods, solutions, and prospects. Appl. Energy 2018, 222, 1033–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munther, H.; Hassan, Q.; Khadom, A.A.; Mahood, H.B. Evaluating the techno-economic potential of large-scale green hydrogen production via solar, wind, and hybrid energy systems utilizing PEM and alkaline electrolyzers. Unconv. Resour. 2025, 5, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydrogen Strategies & Roadmaps. New Zealand Hydrogen Council. Available online: https://www.nzhydrogen.org/strategy-reports-roadmaps-copy (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Kumar, N.; Karmakar, S. Techno-economic optimization of hydrogen generation through hybrid energy system: A step towards sustainable development. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 55, 400–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Energy Perspective 2023: Hydrogen Outlook. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/oil-and-gas/our-insights/global-energy-perspective-2023-hydrogen-outlook (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Draft National Green Hydrogen Strategy for Jordan. Available online: https://www.memr.gov.jo/EBV4.0/Root_Storage/AR/EB_Info_Page/GH2_Strategy.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Geopolitics of the Energy Transformation: The Hydrogen Factor. Available online: https://www.irena.org/Digital-Report/Geopolitics-of-the-Energy-Transformation?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- GFA Consulting Group GmbH; Uhrorakeye, T.; Ruet, J.; Cloete, B.; Bani, J.; Miram, L. African Green Hydrogen Report; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH: Eschborn, Germany, 2025; Available online: https://ptx-hub.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/African-Green-Hydrogen-Report-2025.pdf?utm_source=www.hydrogen-rising.com&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=africa-s-hydrogen-execution-gap-set-to-start-closing-by-2026 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Global Hydrogen Flows. Hydrogen Council, 2022. Available online: https://hydrogencouncil.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Global-Hydrogen-Flows.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Kiwan, S.; Al-Gharibeh, E. Jordan toward a 100% renewable electricity system. Renew. Energy 2020, 147, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan as a Regional Center for Green Hydrogen. Available online: https://www.memr.gov.jo/En/NewsDetails/202502262 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- The GH2 Country Portal. Green Hydrogen Organisation. Available online: http://gh2.org/countries (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- H2 Infrastructure Map Europe. Available online: https://www.h2inframap.eu/ (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Africa Energy Outlook 2022, IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/africa-energy-outlook-2022/key-findings (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). World Energy Outlook 2024; International Energy Agency (IEA): Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/140a0470-5b90-4922-a0e9-838b3ac6918c/WorldEnergyOutlook2024.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Rehman, S.; Kotb, K.M.; Zayed, M.E.; Menesy, A.S.; Irshad, K.; Alzahrani, A.S.; Mohandes, M.A. Techno-economic evaluation and improved sizing optimization of green hydrogen production and storage under higher wind penetration in Aqaba Gulf. J. Energy Storage 2024, 99, 113368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigljević, B.; Byun, M.; Lim, H. Design, economic evaluation, and market uncertainty analysis of LOHC-based, CO2 free, hydrogen delivery systems. Appl. Energy 2020, 274, 115314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, S.; Elkhouly, H.I.; Al Muflih, A.; Harraz, N. Hybrid renewable hydrogen systems in Saudi Arabia: A techno-economic evaluation for three diverse locations. Renew. Energy 2024, 237, 121740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zghaibeh, M.; Belgacem, I.B.; Baloch, M.H.; Chauhdary, S.T.; Kumar, L.; Arici, M. Optimization of green hydrogen production in hydroelectric-photovoltaic grid connected power station. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Manoo, M.U.; Ahmed, J.; Arıcı, M.; Awad, M.M. Comparative techno-economic investigation of hybrid energy systems for sustainable energy solution. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 104, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, K.; Chand, S.S.; Prasad, R.; Mohammadi, A.; Cirrincione, M. Microgrids for green hydrogen production for fuel cell buses—A techno-economic analysis for Fiji. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 300, 117928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiar, B.; Fadlallah, S.O.; Serradj, D.E.B.; Graham, P.; Aagela, H. Navigating Algeria towards a sustainable green hydrogen future to empower North Africa and Europe’s clean hydrogen transition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 61, 783–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahmodi, M.; Ayadi, O.; Al-Halhouli, A.A. Parametric modeling of green hydrogen production in solar PV-CSP hybrid plants: A techno-economic evaluation approach. Energy 2024, 313, 133943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahmodi, M.; Ayadi, O.; Wang, Y.; Al-Halhouli, A.A. Sensitivity-based techno-economic assessment approach for electrolyzer integration with hybrid photovoltaic-wind plants for green hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 97, 904–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, M.; Alsotary, O.; Juaidi, A.; Albatayneh, A.; Alzoubi, A.; Gorjian, S. Potential of Producing Green Hydrogen in Jordan. Energies 2022, 15, 9039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghussain, L.; Ahmad, A.D.; Abubaker, A.M.; Hassan, M.A. Exploring the feasibility of green hydrogen production using excess energy from a country-scale 100% solar-wind renewable energy system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 21613–21633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shboul, B.; Zayed, M.E.; Marashdeh, H.F.; Al-Smad, S.N.; Al-Bourini, A.A.; Amer, B.J.; Qtashat, W.; Alhourani, A.M. Comprehensive assessment of green hydrogen potential in Jordan: Economic, environmental and social perspectives. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2024, 18, 2212–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cruz-soto, J.; Azkona-Bedia, I.; Cornejo-Jimenez, C.; Romero-Castanon, T. Assessment of levelized costs for green hydrogen production for the national refineries system in Mexico. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 108, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.H.; Anwar, M.; Kazmi, S.A.A.; Hassan, M.; Bahadar, A. Techno-economic and composite performance assessment of fuel cell-based hybrid energy systems for green hydrogen production and heat recovery. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 104, 444–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouadje, B.A.M.; Kapen, P.T.; Chegnimonhan, V.; Tchinda, R. Techno-economic analysis of a grid/fuel cell/PV/electrolyzer system for hydrogen and electricity production in the countries of African and Malagasy council for higher education (CAMES). Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 53, 101392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktekin, M.; Genç, M.S.; Azgın, S.T.; Genç, G. Assessment of techno-economic analyzes of grid-connected nuclear and PV/wind/battery/hydrogen renewable hybrid system for sustainable and clean energy production in Mersin-Türkiye. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 190, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, H. Design and optimization of hybrid renewable energy systems for hydrogen production at Aksaray University campus. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 192, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonkwo, P.C. A case study on hydrogen refueling station techno-economic viability. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laila, J.; Anwar, M.; Hassan, M.; Kazmi, S.A.A.; Muhammed Ali, S.A.; Rafique, M.Z. Techno-economic analysis of green hydrogen production from wind and solar along CPEC special economic zones in Pakistan. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 96, 811–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk-Allah, R.M.; Hassan, I.A.; Snasel, V.; Hassanien, A.E. An optimal standalone wind-photovoltaic power plant system for green hydrogen generation: Case study for hydrogen refueling station. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalbasi, R.; Jahangiri, M.; Tahmasebi, A. Comprehensive Investigation of Solar-Based Hydrogen and Electricity Production in Iran. Int. J. Photoenergy 2021, 2021, 6627491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, C.; Nucara, A.; Panzera, M.F.; Pietrafesa, M.; Varano, V. Energetic and economic analysis of a stand alone photovoltaic system with hydrogen storage. Renew. Energy 2019, 142, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qolipour, M.; Mostafaeipour, A.; Tousi, O.M. Techno-economic feasibility of a photovoltaic-wind power plant construction for electric and hydrogen production: A case study. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 78, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangiri, M.; Soulouknga, M.H.; Bardei, F.K.; Shamsabadi, A.A.; Akinlabi, E.T.; Sichilalu, S.M.; Mostafaeipour, A. Techno-econo-environmental optimal operation of grid-wind-solar electricity generation with hydrogen storage system for domestic scale, case study in Chad. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 28613–28628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Orabi, A.M.; Osman, M.G.; Sedhom, B.E. Analysis of the economic and technological viability of producing green hydrogen with renewable energy sources in a variety of climates to reduce CO2 emissions: A case study in Egypt. Appl. Energy 2023, 338, 120958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ourya, I.; Nabil, N.; Abderafi, S.; Boutammachte, N.; Rachidi, S. Assessment of green hydrogen production in Morocco, using hybrid renewable sources (PV and wind). Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 37428–37442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akarsu, B.; Genç, M.S. Optimization of electricity and hydrogen production with hybrid renewable energy systems. Fuel 2022, 324, 124465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Micco, S.; Romano, F.; Jannelli, E.; Perna, A.; Minutillo, M. Techno-economic analysis of a multi-energy system for the co-production of green hydrogen, renewable electricity and heat. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 31457–31467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wei, Q.S.; Oh, B.S. Cost analysis of off-grid renewable hybrid power generation system on Ui Island, South Korea. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 13199–13212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökçek, M.; Kale, C. Techno-economical evaluation of a hydrogen refuelling station powered by Wind-PV hybrid power system: A case study for İzmir-Çeşme. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 10615–10625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyal, S.H.; Mentis, D.; Howells, M. Economic analysis of standalone wind-powered hydrogen refueling stations for road transport at selected sites in Sweden. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 9855–9865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Orabi, A.M.; Osman, M.G.; Sedhom, B.E. Evaluation of green hydrogen production using solar, wind, and hybrid technologies under various technical and financial scenarios for multi-sites in Egypt. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 38535–38556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, T.; Emami, K.; Shah, R.; Hassan, N.M.S.; Anderson, J.; Thomas, D.; Louis, A. A study on green hydrogen-based isolated microgrid. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhoumi, E.M.; Okonkwo, P.C.; Belgacem, I.B.; Zghaibeh, M.; Tlili, I. Optimal sizing of photovoltaic systems based green hydrogen refueling stations case study Oman. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 31964–31973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, T.; Emami, K.; Shah, R.; Hassan, N.M.S.; Belokoskov, V.; Ly, M. Techno-economic Assessment of a Hydrogen-based Islanded Microgrid in North-east. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 3380–3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhoumi, E.M.; Salhi, M.S.; Okonkwo, P.C.; Belgacem, I.B.; Farhani, S.; Zghaibeh, M.; Bacha, F. Techno-economic optimization of wind energy based hydrogen refueling station case study Salalah city Oman. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 9529–9539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Gu, Y.; Tang, Z.; Wang, D.; Wu, Q. Optimal design and techno-economic assessment of low-carbon hydrogen supply pathways for a refueling station located in Shanghai. Energy 2021, 237, 121584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Shaikh, M.A.; Soomro, A.M.; Kazmi, S.A.A.; Kumar, A. Techno-economic comparative analysis of an off-grid PV-wind-hydrogen based EV charging station under four climatically distinct cities in Pakistan. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 93, 1268–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Making The Breakthrough: Green Hydrogen Policies and Technology Costs; International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA): Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2021; Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2020/Nov/IRENA_Green_Hydrogen_breakthrough_2021.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Al Garni, H.Z.; Awasthi, A. Solar PV power plant site selection using a GIS-AHP based approach with application in Saudi Arabia. Appl. Energy 2017, 206, 1225–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiner, D.; Thoma, C.; Bogdanov, D.; Breyer, C. Seasonal hydrogen storage for residential on- and off-grid solar photovoltaics prosumer applications: Revolutionary solution or niche market for the energy transition until 2050? Appl. Energy 2023, 340, 121009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Solar Atlas. Available online: https://globalsolaratlas.info/download/jordan (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Global Wind Atlas. Available online: https://globalwindatlas.info (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- McKenna, R.; Hollnaicher, S.; Fichtner, W. Cost-potential curves for onshore wind energy: A high-resolution analysis for Germany. Appl. Energy 2014, 115, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasihi, M.; Weiss, R.; Savolainen, J.; Breyer, C. Global potential of green ammonia based on hybrid PV-wind power plants. Appl. Energy 2021, 294, 116170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan Inks Four New Deals to Further Green Hydrogen Ambitions, Jordan News Agency-Petra. Available online: https://www.petra.gov.jo/Include/InnerPage.jsp?ID=54528&lang=en&name=en_news (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- Abuzayed, A.; Liebensteiner, M.; Hartmann, N. Hydrogen-ready power plants: Optimizing pathways to a decarbonized energy system in Germany. Appl. Energy 2025, 395, 126228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, P.; Dobos, A.; DiOrio, N.; Freeman, J.; Janzou, S.; Ryberg, D. SAM Photovoltaic Model Technical Reference Update; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Denver, CO, USA, 2018. Available online: https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy18osti/67399.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Freeman, J.; Jorgenson, J.; Gilman, P.; Ferguson, T. Reference Manual for the System Advisor Model’s Wind Power Performance Model; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Denver, CO, USA, 2014. Available online: https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy14osti/60570.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- HOMER Pro 3.16 Glossary. Available online: https://support.ul-renewables.com/homer-manual-pro/glossary.html (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Timmerberg, S.; Kaltschmitt, M. Hydrogen from renewables: Supply from North Africa to Central Europe as blend in existing pipelines—Potentials and costs. Appl. Energy 2019, 237, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Electric Power Company. The Electricity Sector Master Plan in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan; National Electric Power Company (NEPCO): Amman, Jordan, 2017; Available online: https://openjicareport.jica.go.jp/pdf/12283693_01.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- IRENA. Green Hydrogen Cost Reduction; International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA): Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2020; Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/%202020/Dec/IRENA_Green_hydrogen_cost_2020.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- IRENA. Future of Solar Photovoltaic; International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA): Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2019; Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2019/Nov/IRENA_Future_of_Solar_PV_2019.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- IRENA. Future of Wind; International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA): Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2019; Available online: https://safety4sea.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/IRENA-Future-of-wind-2019_10.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- IRENA. Electricity Storage and Renewables: Costs and Markets to 2030; International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA): Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2017; Available online: https://www.climateaction.org/images/uploads/documents/IRENA_Electricity_Storage_Costs_2017.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Viswanathan, V.; Mongird, K.; Franks, R.; Li, X.; Sprenkle, V.; Baxter, R. 2022 Grid Energy Storage Technology Cost and Performance Assessment; Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL): Richland, WA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.pnnl.gov/sites/default/files/media/file/ESGC%20Cost%20Performance%20Report%202022%20PNNL-33283.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Kubes, C.; Slawsky, L.; Bellino, A.; Branner, H.; Miller, M.; LaRusso, T.; Hohnson, L. Review of Projections Through 2040 of U.S. Clean Hydrogen Production, Infrastructure, and Costs; Environmental Resources Management (ERM): London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.sustainability.com/globalassets/caelp_review-h2-projections-through-2040_08-08-23.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2025).

Figure 1.

Study methodology flowchart.

Figure 1.

Study methodology flowchart.

Figure 3.

(a) Average solar GHI heatmap for Jordan (source: Global Solar Atlas); (b) average wind speed heatmap for Jordan (source: Global Wind Atlas).

Figure 3.

(a) Average solar GHI heatmap for Jordan (source: Global Solar Atlas); (b) average wind speed heatmap for Jordan (source: Global Wind Atlas).

Figure 4.

(a) Per-unit hydrogen hourly load scaled with a daily target. (b) Per-unit BOP electrical hourly load scaled with a daily target.

Figure 4.

(a) Per-unit hydrogen hourly load scaled with a daily target. (b) Per-unit BOP electrical hourly load scaled with a daily target.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the proposed system for GH2 production.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the proposed system for GH2 production.

Figure 6.

LCOH indicator results over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer cost variations.

Figure 6.

LCOH indicator results over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer cost variations.

Figure 7.

LCOH indicator results over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer efficiency variations.

Figure 7.

LCOH indicator results over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer efficiency variations.

Figure 8.

LCOH indicator results over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer lifetime variations.

Figure 8.

LCOH indicator results over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer lifetime variations.

Figure 9.

LCOH indicator results over sensitivity variations: PV cost variations.

Figure 9.

LCOH indicator results over sensitivity variations: PV cost variations.

Figure 10.

LCOH indicator results over sensitivity variations: wind cost variations.

Figure 10.

LCOH indicator results over sensitivity variations: wind cost variations.

Figure 11.

LCOE indicator results over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer cost variations.

Figure 11.

LCOE indicator results over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer cost variations.

Figure 12.

LCOE indicator results over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer efficiency variations.

Figure 12.

LCOE indicator results over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer efficiency variations.

Figure 13.

LCOE indicator results over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer lifetime variations.

Figure 13.

LCOE indicator results over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer lifetime variations.

Figure 14.

LCOE indicator results over sensitivity variations: PV cost variations.

Figure 14.

LCOE indicator results over sensitivity variations: PV cost variations.

Figure 15.

LCOE indicator results over sensitivity variations: wind cost variations.

Figure 15.

LCOE indicator results over sensitivity variations: wind cost variations.

Figure 16.

NPV indicator results over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer cost variations.

Figure 16.

NPV indicator results over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer cost variations.

Figure 17.

NPV indicator results over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer efficiency variations.

Figure 17.

NPV indicator results over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer efficiency variations.

Figure 18.

NPV indicator results over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer lifetime variations.

Figure 18.

NPV indicator results over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer lifetime variations.

Figure 19.

NPV indicator results over sensitivity variations: PV cost variations.

Figure 19.

NPV indicator results over sensitivity variations: PV cost variations.

Figure 20.

NPV indicator results over sensitivity variations: wind cost variations.

Figure 20.

NPV indicator results over sensitivity variations: wind cost variations.

Figure 21.

PV, wind, and electrolyzer optimized capacities over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer cost variations.

Figure 21.

PV, wind, and electrolyzer optimized capacities over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer cost variations.

Figure 22.

PV, wind, and electrolyzer optimized capacities over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer efficiency variations.

Figure 22.

PV, wind, and electrolyzer optimized capacities over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer efficiency variations.

Figure 23.

PV, wind, and electrolyzer optimized capacities over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer lifetime variations.

Figure 23.

PV, wind, and electrolyzer optimized capacities over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer lifetime variations.

Figure 24.

PV, wind, and electrolyzer optimized capacities over sensitivity variations: PV cost variations.

Figure 24.

PV, wind, and electrolyzer optimized capacities over sensitivity variations: PV cost variations.

Figure 25.

PV, wind, and electrolyzer optimized capacities over sensitivity variations: wind cost variations.

Figure 25.

PV, wind, and electrolyzer optimized capacities over sensitivity variations: wind cost variations.

Figure 26.

Fuel cell and hydrogen storage tank optimized sizes over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer cost variations.

Figure 26.

Fuel cell and hydrogen storage tank optimized sizes over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer cost variations.

Figure 27.

Fuel cell and hydrogen storage tank optimized sizes over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer efficiency variations.

Figure 27.

Fuel cell and hydrogen storage tank optimized sizes over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer efficiency variations.

Figure 28.

Fuel cell and hydrogen storage tank optimized sizes over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer lifetime variations.

Figure 28.

Fuel cell and hydrogen storage tank optimized sizes over sensitivity variations: electrolyzer lifetime variations.

Figure 29.

Fuel cell and hydrogen storage tank optimized sizes over sensitivity variations: PV cost variations.

Figure 29.

Fuel cell and hydrogen storage tank optimized sizes over sensitivity variations: PV cost variations.

Figure 30.

Fuel cell and hydrogen storage tank optimized sizes over sensitivity variations: wind cost variations.

Figure 30.

Fuel cell and hydrogen storage tank optimized sizes over sensitivity variations: wind cost variations.

Table 1.

Summary of previous HRES optimization studies for GH2 production.

Table 1.

Summary of previous HRES optimization studies for GH2 production.

| Ref. | Year | Location | Application | Electrolyzer

Technology | Connection

Type | LCOE

(USD/kWh) | LCOH

(USD/kg) |

|---|

| [2] | 2025 | Iraq | Large-scale hydrogen production | PEM, AWE | Off-Grid | 0.0045 | 1.98–2.72 |

| [4] | 2024 | India | Hydrogen-fueled buses | N/A | Off-Grid | 0.087 | 3.79 |

| [16] | 2024 | Saudi Arabia | Large-scale hydrogen production | AWE | Both | 0.57 | 5.26 |

| [18] | 2024 | Saudi Arabia | Industrial | N/A 1 | Both | 0.1059 | 0.505 |

| [19] | 2024 | Oman | Grid stability and

hydrogen refueling for transportation | PEM | On Grid | N/A | 2.33 |

| [20] | 2025 | Pakistan | Industrial power

demand | PEM | Off-Grid | 0.86–0.886 | 1.13–1.8 |

| [21] | 2024 | Fiji | Fuel cell buses | AWE | Both | 0.1 | 8.73–9.08 |

| [22] | 2024 | Algeria | Hydrogen export to

Europe | PEM | Off-Grid | N/A | 3.85 |

| [28] | 2025 | Mexico | Oil refineries | PEM | Both | 0.05 | 4.2 |

| [29] | 2025 | Pakistan | University campus | N/A | Both | 0.1084 | 6.94 |

| [30] | 2024 | Africa | Rural community

electrification | N/A | On Grid | 0.238 | 1.84 |

| [31] | 2024 | Turkey | Residential | N/A | On Grid | 0.3 | 12.6 |

| [32] | 2024 | Turkey | University campus | N/A | Off-Grid | 0.327 | N/A |

| [33] | 2024 | Australia | Refueling station for public transport (Fuel cell buses) | N/A | Off-Grid | 0.423 | 0.375 |

| [34] | 2024 | Pakistan | Steel industry | PEM | Both | 0.682 | 2.12 |

| [35] | 2024 | Czech

Republic | Hydrogen refueling

Station and wastewater treatment | N/A | Off-Grid | N/A | 3.006 |

| [36] | 2021 | Iran | Home-scale | PEM | On Grid | 0.206 | N/A |

| [37] | 2019 | Italy | Public area lighting (standalone system) | PEM | Off-Grid | 0.83 | N/A |

| [38] | 2017 | Iran | Industrial hydrogen supply | PEM | On Grid | 0.572 | N/A |

| [39] | 2019 | Chad | Residential | N/A | Both | 0.507 | 4.695 |

| [40] | 2023 | Egypt | Industrial hydrogen production | PEM | Off-Grid | 0.3085 | 3.94 |

| [41] | 2023 | Morocco | Industrial hydrogen production | PEM | Off-Grid | N/A | 2.54 |

| [42] | 2022 | Turkey | Residential | N/A | Off-Grid | 0.376 | N/A |

| [43] | 2023 | Italy | Industrial utilities and refueling stations | AWE | Off-Grid | 0.054 | 3.49 |

| [44] | 2022 | South Korea | Island electrification | PEM | Off-Grid | 0.366 | N/A |

| [45] | 2018 | Turkey | Refueling station for fuel cellElectric Vehicles (FCEVs) | PEM | Off-Grid | 0.146 | 7.526 |

| [46] | 2015 | Sweden | Refueling station for road transport | AWE | Off-Grid | 0.026 | 5.18 |

| [47] | 2023 | Egypt | A filling station | PEM | Off-Grid | 0.3239 | 4.13 |

| [48] | 2022 | Australia | Isolated microgrid power supply | N/A | Off-Grid | 0.35 | 6.48 |

| [49] | 2022 | Oman | Hydrogen refueling stations | PEM | Both | 0.049 | 5.7 |

| [50] | 2023 | Australia | Islanded microgrid | N/A | Off-Grid | 0.49 | 6.79 |

| [51] | 2023 | Oman | Hydrogen refueling stations | N/A | Both | 0.062 | 6.42 |

| [52] | 2021 | China | Hydrogen refueling station | PEM | Both | 0.039 | 5.61 |

| [53] | 2024 | Pakistan | EV charging station | PEM | Off-Grid | 0.393–0.485 | N/A |

| This Study | 2026 | Jordan | Various applications (i.e export) | Generic | Off-Grid | 0.0072–0.0301 | 1.59–3.49 |

Table 2.

The study’s core scenarios.

Table 2.

The study’s core scenarios.

| Source | Scenario (SC) |

|---|

| IEA | SC 1: Stated Policies (Conservative) |

| SC2: Announced Pledges (Moderate) |

| SC3: Net Zero Emissions by 2050 (Optimistic) |

| IRENA | SC1: Conservative |

| SC2: Optimistic |

Table 3.

The PV plant design parameters.

Table 3.

The PV plant design parameters.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|

| Location | Aqaba Governate, Jordan (long: 35.42 lat: 29.81) |

| Model | SAM Software version 2025.4.16, PVWatts model |

| System Capacity | 1 kWac |

| Lifetime | 25 years |

| Total Module Area | |

| DC/AC Ratio | 1.25 |

| Tilt Angle | 25 degrees |

| Azimuth Angle | 180 degrees |

| Total System Losses | 1% |

Table 4.

The wind plant design parameters.

Table 4.

The wind plant design parameters.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|

| Location | Aqaba Governate, Jordan (long: 35.00 lat: 29.00) |

| Model | SAM Software version 2025.4.16, Wind model |

| Wind Turbine Capacity | 3450 kW |

| Hub Height | 112 m |

| Rotor Diameter | 126 m |

| Lifetime | 25 years |

| Shear Coefficient | 0.14 |

| Total Wake Losses | 1.1% |

| Total Turbine Availability Losses | 5.501% |

| Total Electrical Losses | 2.008% |

| Total Turbine Performance Losses | 3.954 |

Table 5.

The BESS storage design parameters.

Table 5.

The BESS storage design parameters.

| Parameter | 1 h BESS Value | 4 h BESS Value |

|---|

| Nominal Voltage (V) | 600 | 600 |

| Nominal Capacity (kWh) | 1000 | 4220 |

| Nominal Capacity (Ah) | 1670 | 7030 |

| Lifetime (years) | 15 | 15 |

| Round Trip Efficiency (%) | 90 | 90 |

| Minimum State of Charge (SoC) (%) | 20 | 20 |

Table 6.

The electrolyzer design parameters.

Table 6.

The electrolyzer design parameters.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|

| Type | Generic |

| Units Size | 1 kW |

| Base Efficiency | 69 (%) |

| Lifetime | 17 years |

| Specific Energy Consumption | 57 kWh/kg |

Table 7.

The hydrogen storage tank design parameters.

Table 7.

The hydrogen storage tank design parameters.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|

| Type | Generic |

| Units Size | 1 kg |

| Relative to Tank Size | 100% |

| Lifetime | 25 years |

Table 8.

The fuel cell design parameters.

Table 8.

The fuel cell design parameters.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|

| Type | Generic |

| Units Size | 1 kW |

| Minimum Load Ratio | 0% |

| Lower Heating Value | 120 MJ/kg |

| Hydrogen Density | |

| Lifetime | 80,000 h |

Table 9.

The system project economic parameters.

Table 9.

The system project economic parameters.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|

| Nominal Yearly Discount Rate | 6.5% |

| Inflation Yearly Rate | 2% |

| Project Period | 25 years |

| System Fixed Costs | USD 60 million |

Table 10.

PV, wind, BESS, and electrolyzer cost projections.

Table 10.

PV, wind, BESS, and electrolyzer cost projections.

| Component | Parameter | Scenario |

|---|

IEA

Conservative

(SC1) | IEA

Moderate

(SC2) | IEA

Optimistic

(SC3) | IRENA

Conservative

(SC4) | IRENA

Optimistic

(SC5) |

|---|

PV

[15,69] | CAPEX (USD/kW) | 410 | 400 | 400 | 834 | 340 |

| Replacement (USD/kW) | 380 | 320 | 320 | 667 | 272 |

| OPEX (USD/kW/yr) | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

Wind

[15,70] | CAPEX (USD/kW) | 940 | 930 | 920 | 1350 | 800 |

| Replacement (USD/kW) | 752 | 744 | 736 | 1080 | 640 |

| OPEX (USD/kW/yr) | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

BESS

[15,71] | CAPEX (USD/kWh) | 175 | 150 | 145 | 224 | 224 |

| Replacement (USD/kWh) | 140 | 120 | 116 | 179.2 | 179.2 |

| OPEX (USD/kWh/yr) | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| Electrolyzer [15,54] | CAPEX (USD/kW) | 850 | 620 | 560 | 450 | 350 |

| Replacement (USD/kW) | 765 | 496 | 448 | 360 | 280 |

| OPEX (USD/kW/yr) | 40.5 | 35.25 | 30 | 12 | 12 |

Table 11.

Fuel cell and hydrogen storage tank cost projections.

Table 11.

Fuel cell and hydrogen storage tank cost projections.

| Component | Parameter | Value |

|---|

| Fuel Cell [72] | CAPEX (USD/kW) | 425 |

| Replacement (USD/kW) | 340 |

| OPEX (USD/operating hour) | 0.002 |

| Hydrogen Storage Tank [73] | CAPEX (USD/kg) | 400 |

| Replacement (USD/kg) | 320 |

| OPEX (USD/kg/yr) | 36.5 |

Table 12.

Sensitivity variations compared to the defined base case.

Table 12.

Sensitivity variations compared to the defined base case.

| Sensitivity | Base Value | Variation Step | Range |

|---|

| Electrolyzer Cost Factors (pu) | 1 | 0.1 | 0.5–1.5 |