Nanoscale Nickel–Chromium Powder as a Catalyst in Reducing the Temperature of Hydrogen Desorption from Magnesium Hydride

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Preparation

2.2. Analysis and Characterization

2.3. Methods and Calculation Details

3. Results

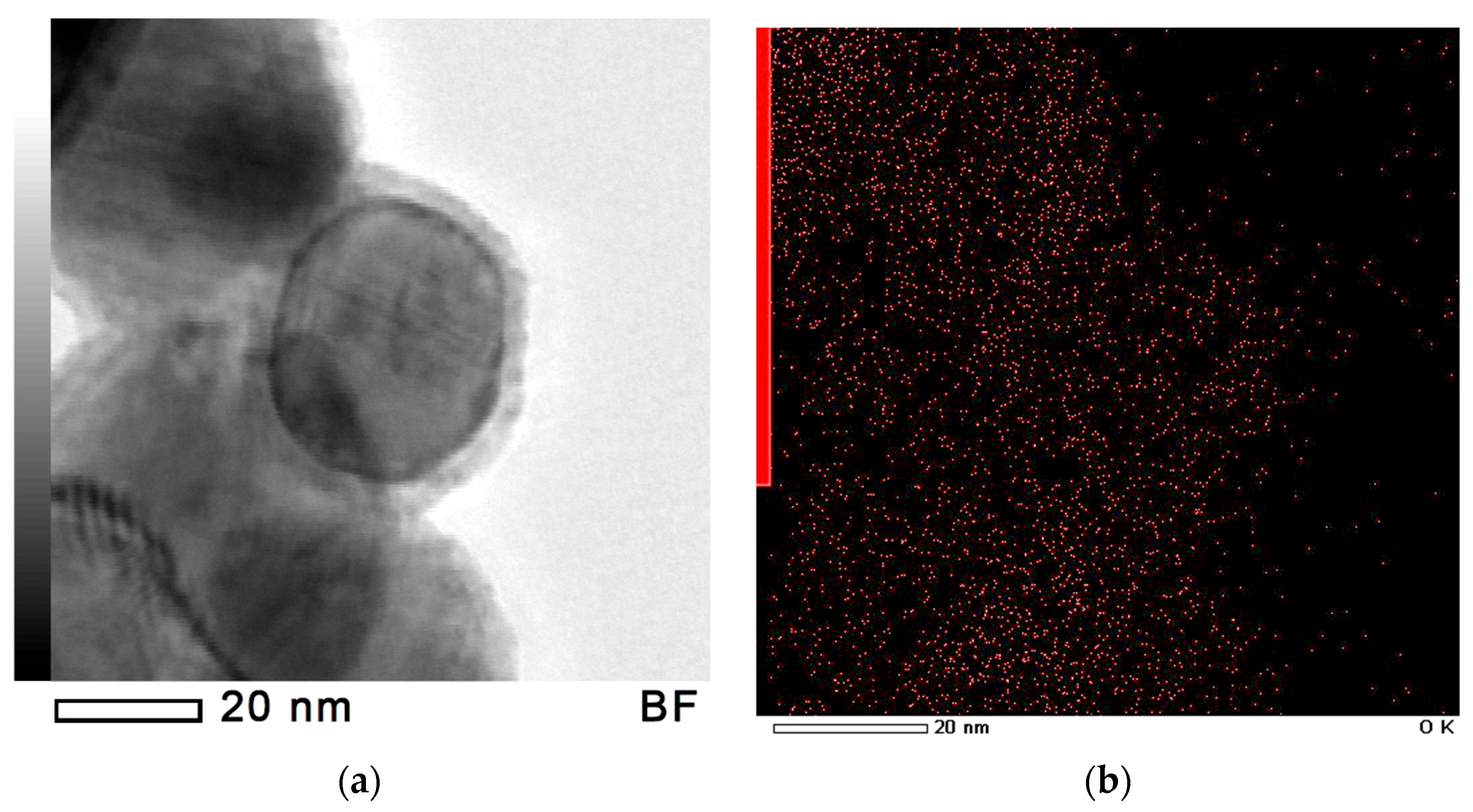

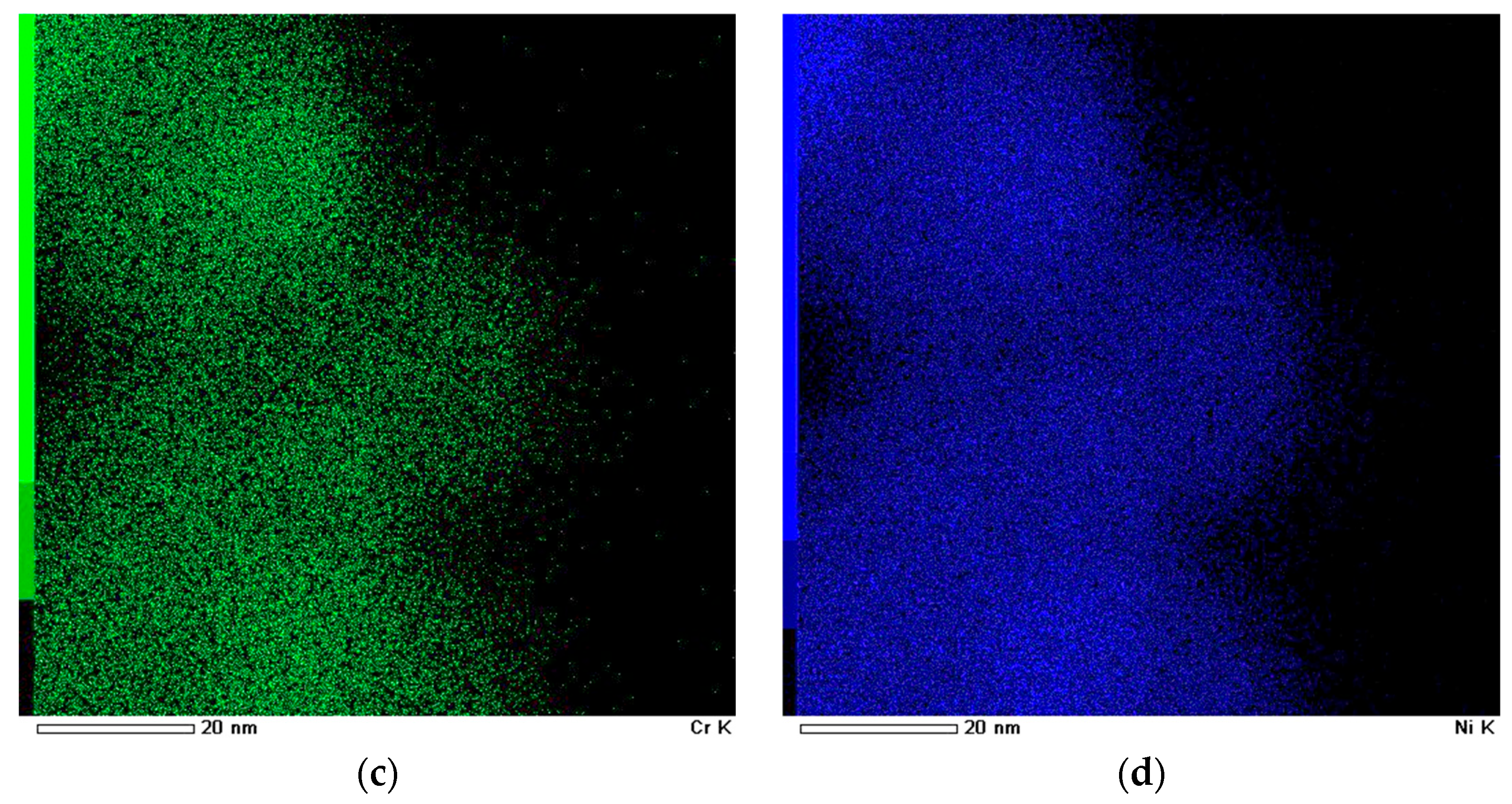

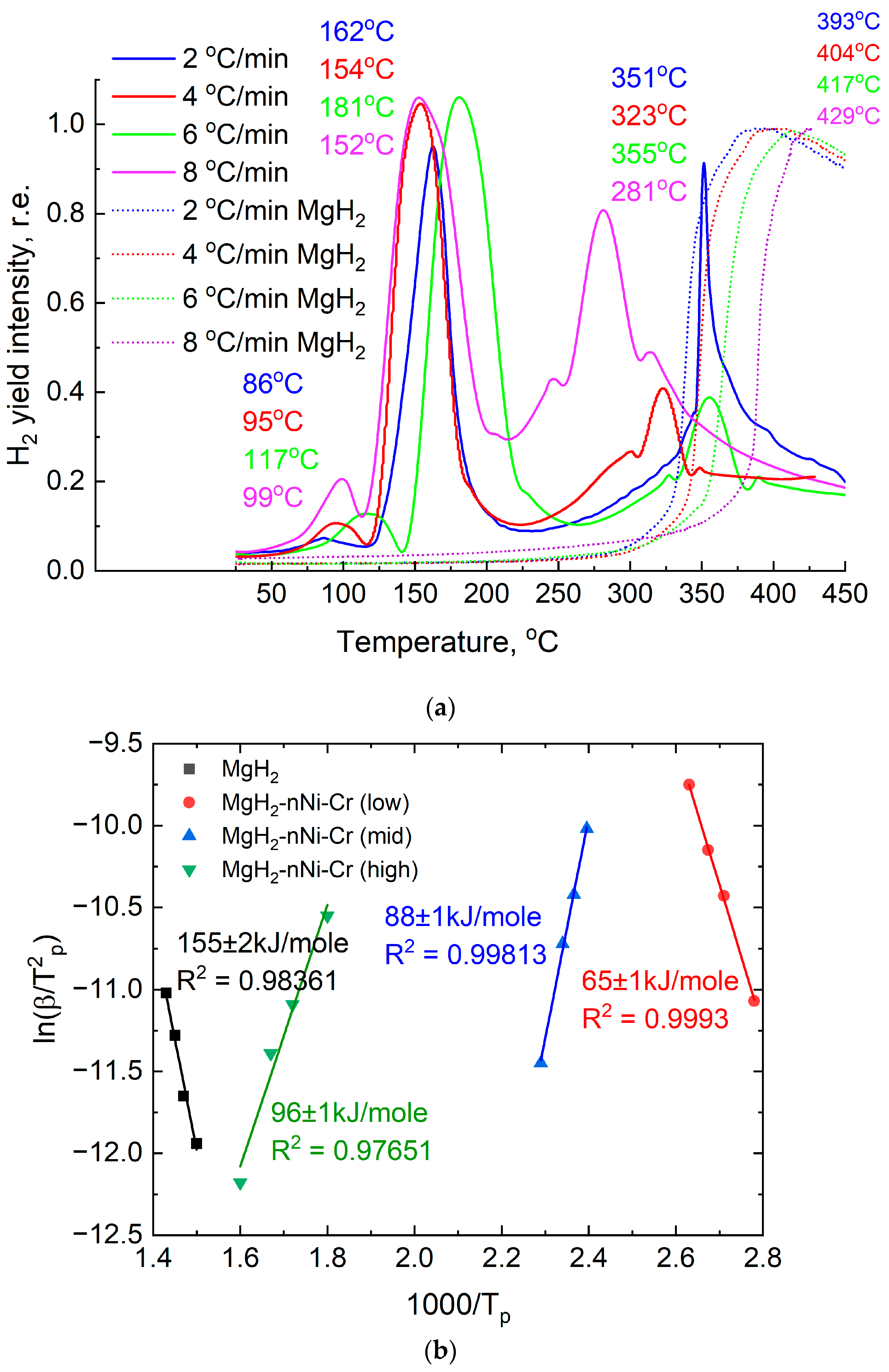

3.1. Composite Characterization

3.2. Hydrogen Storage Properties of Composite

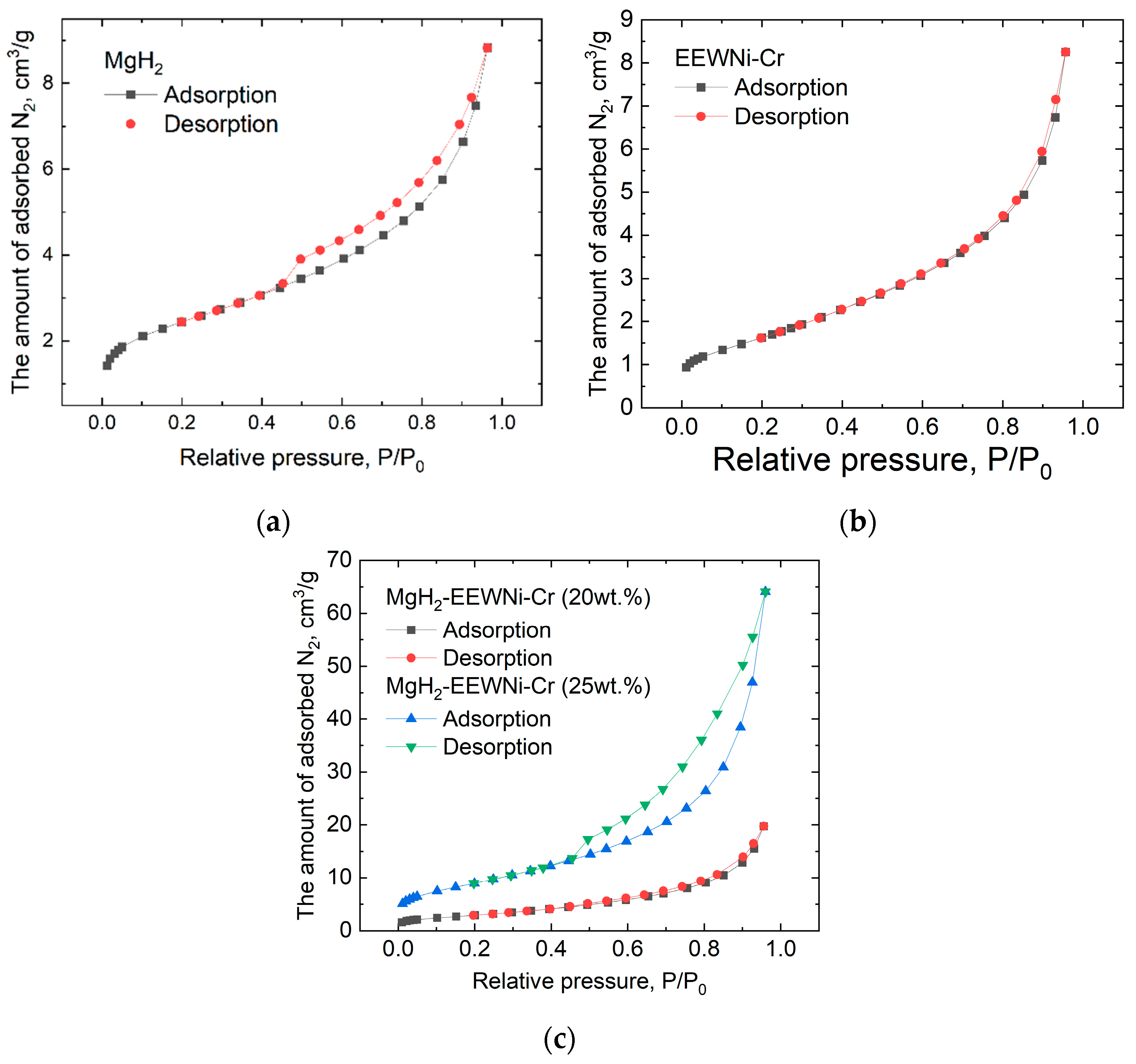

- We attribute the low-temperature hydrogen desorption peak at 86–117 °C mainly to surface dissociation of the hydride and the catalytic effect.

- The hydrogen yield at 152–162 °C is also associated with the catalytic effect of the added material, but the width of the peak and its intensity suggest a bulk decomposition of the hydride phase in the material.

- Hydrogen desorption at 281–351 °C is associated with the full dissociation of the magnesium hydride phase in the composite material, which was subsequently confirmed by the results of In situ XRD in Figure 8 below.

3.3. Influence of the Ni and Cr Additives on H-Mg Bonding

4. Discussion

- Reducing the cost of producing hydrogen, which will be environmentally friendly.

- Research and development in the field of storage and transportation.

- Cooperation between countries to improve the current state of hydrogen energy in the world.

- Investment in the development and implementation of new production technologies [61].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABINIT | Software package, lat. Ab initio (“from the beginning”)—first-principles calculations |

| DFT | Density functional theory |

| Eb | Binding energy |

| Ed | Desorption activation energy |

| EEW | Electrical explosion of wires |

| MPF-4 | Magnesium Powder Fraction-4 |

| GRAM50 | Gas Reaction Automated Machine 50 bar |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| EDX | Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| BET | Brunauer–Emmet–Teller method |

| BJH | Barrett–Joyner–Halenda method |

| TPD | Temperature-programmed desorption |

| RGA | Residual Gas Analyzer |

| JCPDS | Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards |

| HCP | Hexagonal close-packed lattice |

| BCC | Base-centered cubic lattice |

| FCC | Face-centered cubic lattice |

References

- Abdi Lanbaran, D.; Wang, C.; Wen, C.; Wu, Z.; Li, B. Modeling the Impact of Temperature-Dependent Thermal Conductivity on Hydrogen Desorption from Magnesium Hydride. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 138, 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudiiarov, V.N.; Kenzhiyev, A.; Kurdyumov, N.; Elman, R.R.; Svyatkin, L.A.; Terenteva, D.V. Superior Catalytic Activity of Nano Sized Ni Produced by Electrical Explosion of Wires towards the Hydrogen Storage of Magnesium Hydride. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 109, 436–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mao, W.; Su, Y.; Liu, B.; Ji, W. Investigation on Explosion Overpressure and Flame Propagation Characteristics of Magnesium Hydride Dust of Different Particle Sizes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 101, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudiiarov, V.N.; Kenzhiyev, A.; Elman, R.R.; Kurdyumov, N.; Ushakov, I.A.; Tereshchenko, A.V.; Laptev, R.S.; Kruglyakov, M.A.; Khomidzoda, P.I. The Defect Structure Evolution in MgH2-EEWNi Composites in Hydrogen Sorption–Desorption Processes. Metals 2025, 15, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drawer, C.; Lange, J.; Kaltschmitt, M. Metal Hydrides for Hydrogen Storage—Identification and Evaluation of Stationary and Transportation Applications. J. Energy Storage 2024, 77, 109988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudiiarov, V.; Elman, R.; Pushilina, N.; Kurdyumov, N. State of the Art in Development of Heat Exchanger Geometry Optimization and Different Storage Bed Designs of a Metal Hydride Reactor. Materials 2023, 16, 4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, P.; Rathi, B.; Agarwal, S.; Juyal, S.; Gill, F.S.; Kumar, M.; Saini, P.; Dixit, A.; Ichikawa, T.; Jain, A. Core-Shell Structured Ni@C Based Additive for Magnesium Hydride System towards Efficient Hydrogen Sorption Kinetics. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 107, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elman, R.; Kudiiarov, V.; Sayadyan, A.; Pushilina, N.; Leng, H. Performance Improvement of Magnesium-Based Hydrogen Storage Tanks by Using Carbon Nanotubes Addition and Finned Heat Exchanger: Numerical Simulation and Experimental Verification. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 92, 1375–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, B.; Agarwal, S.; Shrivastava, K.; Kumar, M.; Jain, A. Recent Advances in Designing Metal Oxide-Based Catalysts to Enhance the Sorption Kinetics of Magnesium Hydride. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 53, 131–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, C.; Sui, Y.; Zhai, T.; Hou, Z.; Han, Z.; Zhang, Y. Research Progress in Improved Hydrogen Storage Properties of Mg-Based Alloys with Metal-Based Materials and Light Metals. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 1401–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Wei, L.; Gong, Y.; Yang, K. Enhanced Hydrogen Storage Properties of Magnesium Hydride by Multifunctional Carbon-Based Materials: A Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 55, 521–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudiiarov, V.N.; Kurdyumov, N.; Elman, R.R.; Laptev, R.S.; Kruglyakov, M.A.; Ushakov, I.A.; Tereshchenko, A.V.; Lider, A.M. The Defect Structure Evolution in Magnesium Hydride/Metal-Organic Framework Structures MIL-101 (Cr) Composite at High Temperature Hydrogen Sorption-Desorption Processes. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 966, 171534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günaydın, Ö.F.; Topçu, S.; Aksoy, A. Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles: Overview and Current Status of Hydrogen Mobility. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 142, 918–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X. Towards Efficient and Safe Hydrogen Storage for Green Shipping: Progress on Critical Technical Issues of Material Development and System Construction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 167, 150913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Ayati, A.; Farrokhi, M.; Khadempir, S.; Rajabzadeh, A.R.; Farghali, M.; Krivoshapkin, P.; Tanhaei, B.; Rooney, D.W.; Yap, P.-S. Innovations in Hydrogen Storage Materials: Synthesis, Applications, and Prospects. J. Energy Storage 2024, 95, 112376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudiiarov, V.N.; Kurdyumov, N.; Elman, R.R.; Svyatkin, L.A.; Terenteva, D.V.; Semyonov, O. Microstructure and Hydrogen Storage Properties of MgH2/MIL-101(Cr) Composite. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 976, 173093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Liu, C.; Feng, Y.; Gao, Z.; Chen, S.; Huang, M.; Ge, H.; Huang, L.; Gao, Z.; Yang, W. Size-Dependent Nanoconfinement Effects in Magnesium Hydride. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 96, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żukowski, W.; Berkowicz-Płatek, G.; Wencel, K.; Migas, P.; Wrona, J.; Reyna-Bowen, L. Hydrogen Production from Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers in a Fluidized-Bed Made out of Co3O4-Cenosphere Catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 136, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Xu, C.; Fan, Q.; Wei, Y.; Qu, D.; Li, X.; Xie, Z.; Tang, H.; Li, J.; Liu, D. Electrochemical Hydrogen Storage in Zeolite Template Carbon and Its Application in a Proton/Potassium Hybrid Ion Hydrogel Battery Coupling with Nickel-Zinc Co-Doped Prussian Blue Analogues. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 122, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, B.; Kundu, A.; Chakraborty, B. High-Capacity Hydrogen Storage in Zirconium Decorated Zeolite Templated Carbon: Predictions from DFT Simulations. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 38671–38681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani, F.Z.; Mohsennia, M. Enhancing Electrochemical Hydrogen Storage in Nickel-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) through Zinc and Cobalt Doping as Bimetallic MOFs. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 101, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.-Q.; Jiang, W.; Si, N.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H. MOF-Derived Carbon Supported Transition Metal (Fe, Ni) and Synergetic Catalysis for Hydrogen Storage Kinetics of MgH2. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 86, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, Q.; He, H. Synergistic Effect of Hydrogen Spillover and Nano-Confined AlH3 on Room Temperature Hydrogen Storage in MOFs: By GCMC, DFT and Experiments. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 72, 1224–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Shi, R.; Shao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, L. Catalysis Derived from Flower-like Ni MOF towards the Hydrogen Storage Performance of Magnesium Hydride. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 9346–9356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, A.; Kumar, A. MOFs and MOF Derivatives for Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Reaction: Designing Strategies, Syntheses and Future Prospects. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 150, 150148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yong, H.; Wang, S.; Yan, Z.; Xu, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, B.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Y. Investigating of Hydrolysis Kinetics and Catalytic Mechanism of Mg–Ce–Ni Hydrogen Storage Alloy Catalyzed by Ni/Co/Zn-Based MOF. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 71, 1416–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wu, T.; Wang, K.; Wang, Q.; Mei, X.; Huang, J.; Liu, H.; Huang, C.; Guo, J. Synergistic Dual-Modification Regulation of Dehydrogenation Kinetics of MgH2 by MOF-Derived Core-Shell Ni&C. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 127, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamçıçıer, Ç.; Kürkçü, C. Investigation of Structural, Electronic, Elastic, Vibrational, Thermodynamic, and Optical Properties of Mg2NiH4 and Mg2RuH4 Compounds Used in Hydrogen Storage. J. Energy Storage 2024, 84, 110883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapsi, M.; Veziri, C.M.; Pilatos, G.; Karanikolos, G.N.; Romanos, G.E. Zeolite-Templated Sub-Nanometer Carbon Nanotube Arrays and Membranes for Hydrogen Storage and Separation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 36850–36872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Chai, X.; Gu, Y.; Wu, W.; Ma, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, T. Advances in Hydrogen Storage Materials for Physical H2 Adsorption. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 97, 1261–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worth, J.D.; Ting, V.P.; Faul, C.F.J. Exploring Conjugated Microporous Polymers for Hydrogen Storage: A Review of Current Advances. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 152, 149718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain Bhuiyan, M.M.; Siddique, Z. Hydrogen as an Alternative Fuel: A Comprehensive Review of Challenges and Opportunities in Production, Storage, and Transportation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 102, 1026–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.J.; Ramadhani, S.; Ha, T.; Kim, E.-Y.; Baek, J.; Jeong, D.; Park, G.; Kim, J.; Lee, Y.-S.; Shim, J.-H.; et al. Dual Functionality of LaNi5 Metal Hydride as a Catalyst for Toluene Hydrogenation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 167, 150891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chabane, D.; Elkedim, O. Optimization of LaNi5 Hydrogen Storage Properties by the Combination of Mechanical Alloying and Element Substitution. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 53, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiangviriya, S.; Thongtan, P.; Thaweelap, N.; Plerdsranoy, P.; Utke, R. Heat Charging and Discharging of Coupled MgH2–LaNi5 Based Thermal Storage: Cycling Stability and Hydrogen Exchange Reactions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, B.; Ilbas, M.; Celik, S. Experimental Analysis of Hydrogen Storage Performance of a LaNi5–H2 Reactor with Phase Change Materials. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 6010–6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibani, A.; Boucetta, C.; Haddad, M.A.N.; Boukhari, A.; Fourar, I.; Merouani, S.; Badji, R.; Adjel, S.; Belkhiria, S.; Boukraa, M.; et al. A Novel Metal Hydride Reactor Design: The Effect of Using Copper, AlN and AlSi10Mg Composite Fins on the Dehydrogenation Process of LaNi5-Metal Alloy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 141, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra Mouli, B.; Sharma, V.K.; Paswan, M.; Thomas, B. Performance Investigations on Thermochemical Energy Storage System Using Cerium, Aluminium, Manganese, and Tin-Substituted LaNi5 Hydrides. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 96, 1203–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikeng, E.; Makhsoos, A.; Pollet, B.G. Critical and Strategic Raw Materials for Electrolysers, Fuel Cells, Metal Hydrides and Hydrogen Separation Technologies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 71, 433–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parviz, R.; Heydarinia, A.; Nili-Ahmadabadi, M. Enhanced Hydrogen Storage via In-Situ Formation of Oxide, Metallic and Intermetallic Catalysts in a Mg-Based Porous-Layered Composite. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 111, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, V.B.; Júnior, W.O.; Gonzalez Cruz, E.D.; Leiva, D.R.; Pereira Da Silva, E. Casting of Mg-Based Alloy with Ni and Mishmetal Addition (Mg88Ni8MM4) for Hydrogen Storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 109, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nivedhitha, K.S.; Banapurmath, N.R.; Yaliwal, V.S.; Umarfarooq, M.A.; Sajjan, A.M.; Venkatesh, R.; Hosmath, R.S.; Beena, T.; Yunus Khan, T.M.; Kalam, M.A.; et al. From Nickel–Metal Hydride Batteries to Advanced Engines: A Comprehensive Review of Hydrogen’s Role in the Future Energy Landscape. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 82, 1015–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yuan, Z.; Li, X.; Man, X.; Zhai, T.; Han, Z.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y. Hydrogen Storage Capabilities Enhancement of MgH2 Nanocrystals. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 88, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanski, M.; Bystrzycki, J.; Varin, R.A.; Plocinski, T.; Pisarek, M. The Effect of Chromium (III) Oxide (Cr2O3) Nanopowder on the Microstructure and Cyclic Hydrogen Storage Behavior of Magnesium Hydride (MgH2). J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 2386–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanski, M.; Bystrzycki, J. Comparative Studies of the Influence of Different Nano-Sized Metal Oxides on the Hydrogen Sorption Properties of Magnesium Hydride. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 486, 697–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pukazhselvan, D.; Çaha, I.; De Lemos, C.; Mikhalev, S.M.; Deepak, F.L.; Fagg, D.P. Understanding the Catalysis of Chromium Trioxide Added Magnesium Hydride for Hydrogen Storage and Li Ion Battery Applications. J. Magnes. Alloys 2024, 12, 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nivedhitha, K.S.; Beena, T.; Banapurmath, N.R.; Umarfarooq, M.A.; Ramasamy, V.; Soudagar, M.E.M.; Ağbulut, Ü. Advances in Hydrogen Storage with Metal Hydrides: Mechanisms, Materials, and Challenges. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 61, 1259–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, D.; Li, J.; Yuan, Z.; Guo, S.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, Y. Hydrogen Storage Property Improvement of La–Y–Mg–Ni Alloy by Ball Milling with TiF3. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 17957–17969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Yao, J.; Yong, H.; Wang, S.; Xu, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hu, J. Investigation of Ball-Milling Process on Microstructure, Thermodynamics and Kinetics of Ce–Mg–Ni-Based Hydrogen Storage Alloy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 11274–11286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonze, X.; Amadon, B.; Antonius, G.; Arnardi, F.; Baguet, L.; Beuken, J.-M.; Bieder, J.; Bottin, F.; Bouchet, J.; Bousquet, E.; et al. The Abinitproject: Impact, Environment and Recent Developments. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2020, 248, 107042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, A.H.; Allan, D.C.; Amadon, B.; Antonius, G.; Applencourt, T.; Baguet, L.; Bieder, J.; Bottin, F.; Bouchet, J.; Bousquet, E.; et al. ABINIT: Overview and Focus on Selected Capabilities. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 124102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, R.F.W. Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990; ISBN 978-0-19-855168-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rzeszotarska, M.; Dworecka-Wójcik, J.; Dębski, A.; Czujko, T.; Polański, M. Magnesium-Based Complex Hydride Mixtures Synthesized from Stainless Steel and Magnesium Hydride with Subambient Temperature Hydrogen Absorption Capability. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 901, 163489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, A.; Li, L. Air Exposure Improving Hydrogen Desorption Behavior of Mg–Ni-Based Hydrides. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 22183–22191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pericoli, E.; Barzotti, A.; Mazzaro, R.; Moury, R.; Cuevas, F.; Pasquini, L. Synthesis and Hydrogen Storage Properties of Mg-Based Complex Hydrides with Multiple Transition Metal Elements. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2025, 8, 4993–5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Wu, F.; Jiang, Y.; Yao, Z.; Chen, L. Promoting Catalysis in Magnesium Hydride for Solid-State Hydrogen Storage through Manipulating the Elements of High Entropy Oxides. J. Magnes. Alloys 2024, 12, 5038–5050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, R.; Lu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Bian, T.; Shang, D.; Zhang, L. Enhanced Hydrogen Storage Performance of Magnesium Hydride Catalyzed by Medium-Entropy Alloy CrCoNi Nanosheets. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahou, S.; Labrim, H.; Ez-Zahraouy, H. Role of Vacancies and Transition Metals on the Thermodynamic Properties of MgH2: Ab-Initio Study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 8179–8188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudiiarov, V.; Elman, R.; Kurdyumov, N.; Laptev, R. The phase transitions behavior and defect structure evolution in magnesium hydride/single-walled carbon nanotubes composite at hydrogen sorption-desorption processes. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 953, 170138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Ullah, A.; Samreen, A.; Qasim, M.; Nawaz, K.; Ahmad, W.; Alnaser, A.; Kannan, A.M.; Egilmez, M. Hydrogen Production, Storage, Transportation and Utilization for Energy Sector: A Current Status Review. J. Energy Storage 2024, 101, 113733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Phases (PowderCell24 cards) | Phase Content, ±0.2 vol.% | Lattice Parameters, ±0.0005 Å | Crystalline Size, ±0.05 nm | Microstrains, ±0.0003 ∆d/d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MgH2 | Mg-00-035-0821 | 16.6 | a = 3.1998 c = 5.1978 | 36.84 | 0.0011 |

| MgH2-00-012-0697_tet | 83.4 | a = 4.5003 c = 3.0142 | 64.98 | 0.0016 | |

| EEWNi-Cr | Cr0.4Ni0.6-04-001-3422 | 100 | a = 3.5540 | 40.49 | 0.0004 |

| MgH2–20 wt.% EEWNi-Cr | Mg-00-035-0821 | 9.7 | a = 3.1950 c = 5.2020 | 7.37 | 0.0054 |

| MgH2-00-012-0697_tet | 85.8 | a = 4.5070 c = 3.0110 | 40.95 | 0.0062 | |

| Cr0.4Ni0.6-04-001-3422 | 4.5 | a = 3.5490 | 23.3 | 0.0011 |

| Element | Mass% | Atom% |

|---|---|---|

| O | 1.41 | 4.86 |

| Cr | 23.39 | 24.68 |

| Ni | 75.20 | 70.46 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Sample | Degassing Vacuum | BET Surface Area, m2/g | Total Pore Volume, cm3/g | Average Pore Diameter, nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MgH2 (0.4347 g) | 10 h 573 K | 8.5 | 0.014 | 6.4 |

| EEWNi-Cr (0.8781 g) | 6.2 | 0.013 | 8.1 | |

| MgH2-EEWNi-Cr (20 wt.%) (0.3409 g) | 10.6 | 0.031 | 11.5 | |

| MgH2-EEWNi-Cr (25 wt.%) (0.2321 g) | 28.5 | 0.099 | 13.9 |

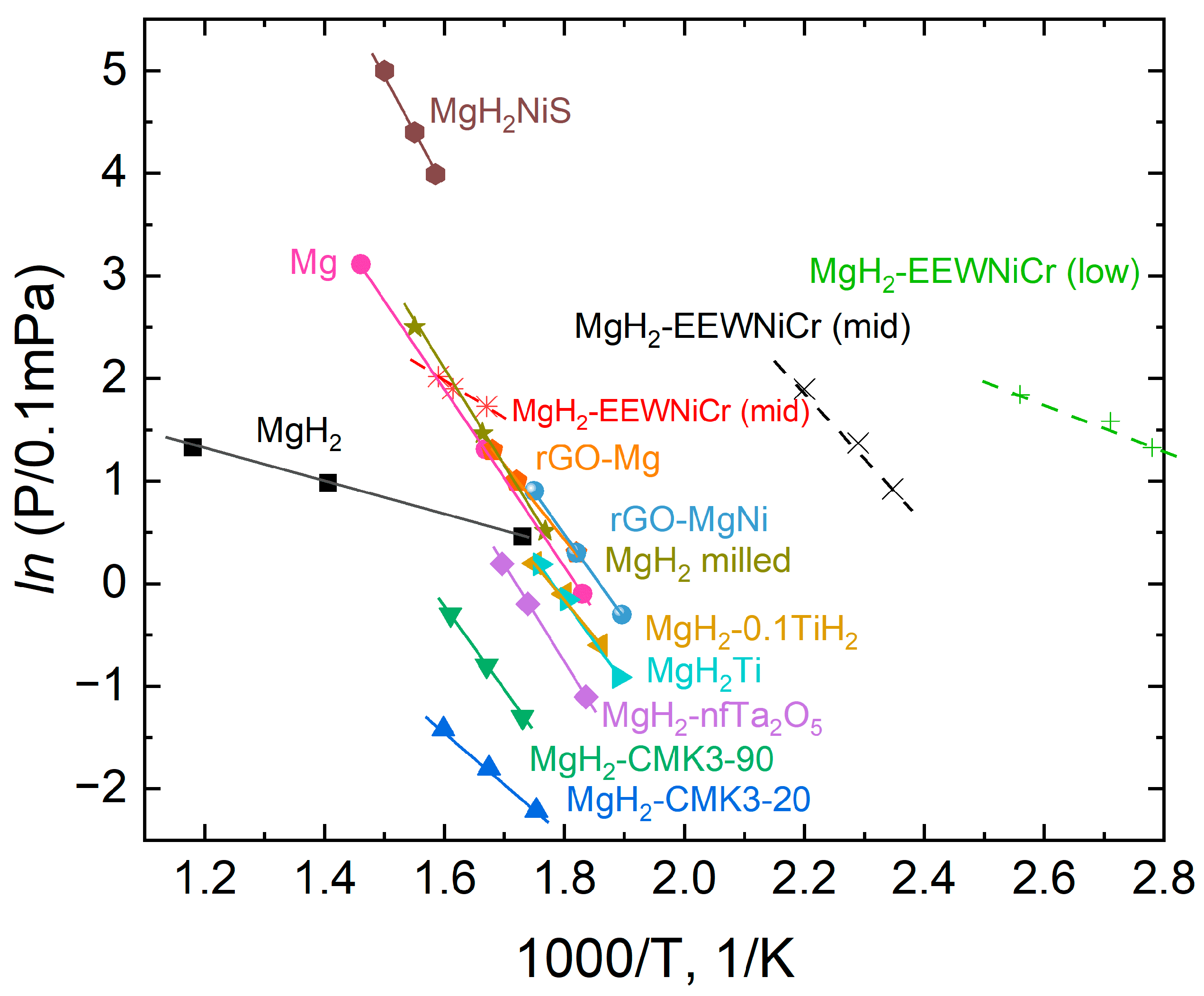

| № | Sample | β, °C/min | TP, K | , | A, Angular Coefficient | Activation Energy of Desorption, kJ/mol | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MgH2 | 2 | 666 | −11.94 | 1.5 | −15.75 | 155 ± 2 |

| 4 | 677 | −11.65 | 1.47 | ||||

| 6 | 690 | −11.28 | 1.45 | ||||

| 8 | 700 | −11.02 | 1.43 | ||||

| 2 (low) | MgH2-EEWNi-Cr | 2 | 359 | −11.07 | 2.78 | −10.66 | 65 ± 1 |

| 4 | 368 | −10.43 | 2.71 | ||||

| 6 | 390 | −10.14 | 2.56 | ||||

| 8 | 372 | −9.75 | 2.68 | ||||

| 3 (mid) | 2 | 435 | −11.45 | 2.29 | 16.19 | 88 ± 1 | |

| 4 | 427 | −10.72 | 2.34 | ||||

| 6 | 454 | −10.44 | 2.20 | ||||

| 8 | 425 | −10.02 | 2.35 | ||||

| 4 (high) | 2 | 624 | −12.18 | 1.60 | 7.98 | 96 ± 1 | |

| 4 | 596 | −11.39 | 1.67 | ||||

| 6 | 628 | −11.09 | 1.59 | ||||

| 8 | 554 | −10.55 | 1.80 |

| System | Position of the H Atom Relative to the Adsorbate, as Defined in Figure 2 | Hydrogen Binding Energy, eV | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distance r from the Mass Center of the Adsorbate | Label | ||

| Mg48H96 | - | H3 | 1.307 |

| H7 | 1.514 | ||

| Mg48H96Ni | r < r1 | H1 | 0.829 |

| H4 | 1.227 | ||

| r1 < r < r2 | H5 | 0.798 | |

| H7 | 0.969 | ||

| r2 < r < r3 | H9 | 1.159 | |

| H10 | 1.106 | ||

| H12 | 1.159 | ||

| H13 | 1.048 | ||

| r3 < r < r4 | H11 | 1.139 | |

| Mg48H96Cr | r < r1 | H1 | 1.071 |

| H4 | 1.369 | ||

| r1 < r < r2 | H5 | 0.461 | |

| H3 | 0.227 | ||

| r2 < r < r3 | H7 | 0.089 | |

| H9 | 0.918 | ||

| r ≈ r4 | H11 | 1.363 | |

| Mg48H96NiCr | r < r1 | H1 | 1.009 |

| H2 | 0.384 | ||

| H3 | 0.922 | ||

| H4 | 0.482 | ||

| r1 < r < r2 | H5 | 0.729 | |

| H6 | 0.626 | ||

| r2 < r < r3 | H7 | 0.208 | |

| H8 | 0.695 | ||

| H9 | 1.016 | ||

| H10 | −0.624 | ||

| r ≈ r5 | H11 | 0.770 | |

| Atom H | , Å | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg48H96 | Mg48H96Ni | Mg48H96Cr | Mg48H96NiCr | |

| H1 | 1.937–1.988 | 1.964–2.335 | 2.117–2.927 | 2.037–2.392 |

| H2 | 1.937–1.988 | 1.886–1.970 | 2.117–2.927 | 1.899–2.983 |

| H3 | 1.865–1.865 | 2.014–2.278 | 1.867–1.914 | 2.005–2.137 |

| H4 | 1.865–1.865 | 2.014–2.278 | 1.987–1.987 | 1.989–2.055 |

| H5 | 1.937–1.988 | 1.914–1.994 | 1.885–1.930 | 1.893–1.911 |

| H6 | 1.937–1.988 | 1.926–1.994 | 1.885–1.930 | 1.888–1.998 |

| H7 | 1.937–1.988 | 1.837–1.957 | 1.958–2.025 | 1.927–1.984 |

| H8 | 1.937–1.988 | 1.960–2.078 | 1.926–2.025 | 1.895–1.934 |

| H9 | 1.865–1.865 | 2.064–2.089 | 1.947–2.089 | 1.977–2.008 |

| H10 | 1.865–1.865 | 2.064–2.089 | 1.869–1.877 | 1.864–1.874 |

| H11 | 1.937–1.988 | 1.879–2.000 | 1.945–2.036 | 1.879–1.992 |

| H12 | 1.865–1.865 | 1.885–1.885 | 1.867–1.914 | 1.858–1.898 |

| H13 | 1.937–1.988 | 1.895–1.957 | 1.954–1.991 | 1.933–1.943 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kenzhiyev, A.; Kudiiarov, V.N.; Spiridonova, A.A.; Terenteva, D.V.; Vrublevskii, D.B.; Svyatkin, L.A.; Nikitin, D.S.; Kashkarov, E.B. Nanoscale Nickel–Chromium Powder as a Catalyst in Reducing the Temperature of Hydrogen Desorption from Magnesium Hydride. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040123

Kenzhiyev A, Kudiiarov VN, Spiridonova AA, Terenteva DV, Vrublevskii DB, Svyatkin LA, Nikitin DS, Kashkarov EB. Nanoscale Nickel–Chromium Powder as a Catalyst in Reducing the Temperature of Hydrogen Desorption from Magnesium Hydride. Hydrogen. 2025; 6(4):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040123

Chicago/Turabian StyleKenzhiyev, Alan, Viktor N. Kudiiarov, Alena A. Spiridonova, Daria V. Terenteva, Dmitrii B. Vrublevskii, Leonid A. Svyatkin, Dmitriy S. Nikitin, and Egor B. Kashkarov. 2025. "Nanoscale Nickel–Chromium Powder as a Catalyst in Reducing the Temperature of Hydrogen Desorption from Magnesium Hydride" Hydrogen 6, no. 4: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040123

APA StyleKenzhiyev, A., Kudiiarov, V. N., Spiridonova, A. A., Terenteva, D. V., Vrublevskii, D. B., Svyatkin, L. A., Nikitin, D. S., & Kashkarov, E. B. (2025). Nanoscale Nickel–Chromium Powder as a Catalyst in Reducing the Temperature of Hydrogen Desorption from Magnesium Hydride. Hydrogen, 6(4), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040123