Delignification of Rice Husk for Biohydrogen-Oriented Glucose Production: Kinetic Analysis and Life Cycle Assessment of Water and NaOH Pretreatments

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- How significantly does increasing the pretreatment temperature beyond 100 °C, compared to room temperature conditions, accelerate lignin removal from rice husk when using water and NaOH during short reaction periods?

- (ii)

- How do the reaction rate constants and activation energies of the optimal kinetic model differ across the various pretreatment conditions?

- (iii)

- How does the degree of lignin removal achieved through water and NaOH pretreatments affect glucose yield during enzymatic hydrolysis?

- (iv)

- Is there a direct relationship between pretreatment effectiveness in lignin solubilization and the magnitude of environmental impacts as measured through LCA?

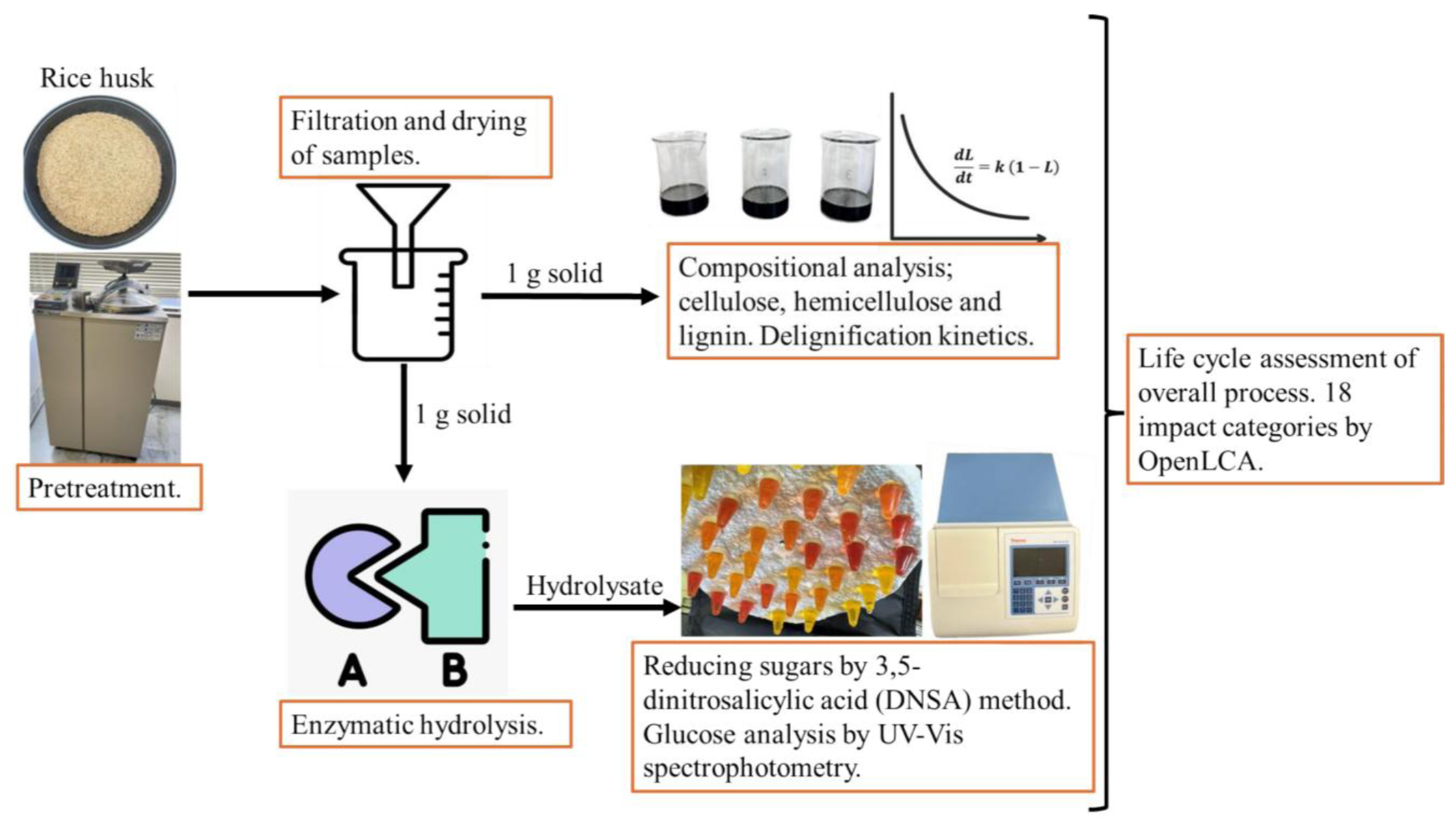

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Material

2.2. RH Pretreatment

2.3. Compositional Analysis

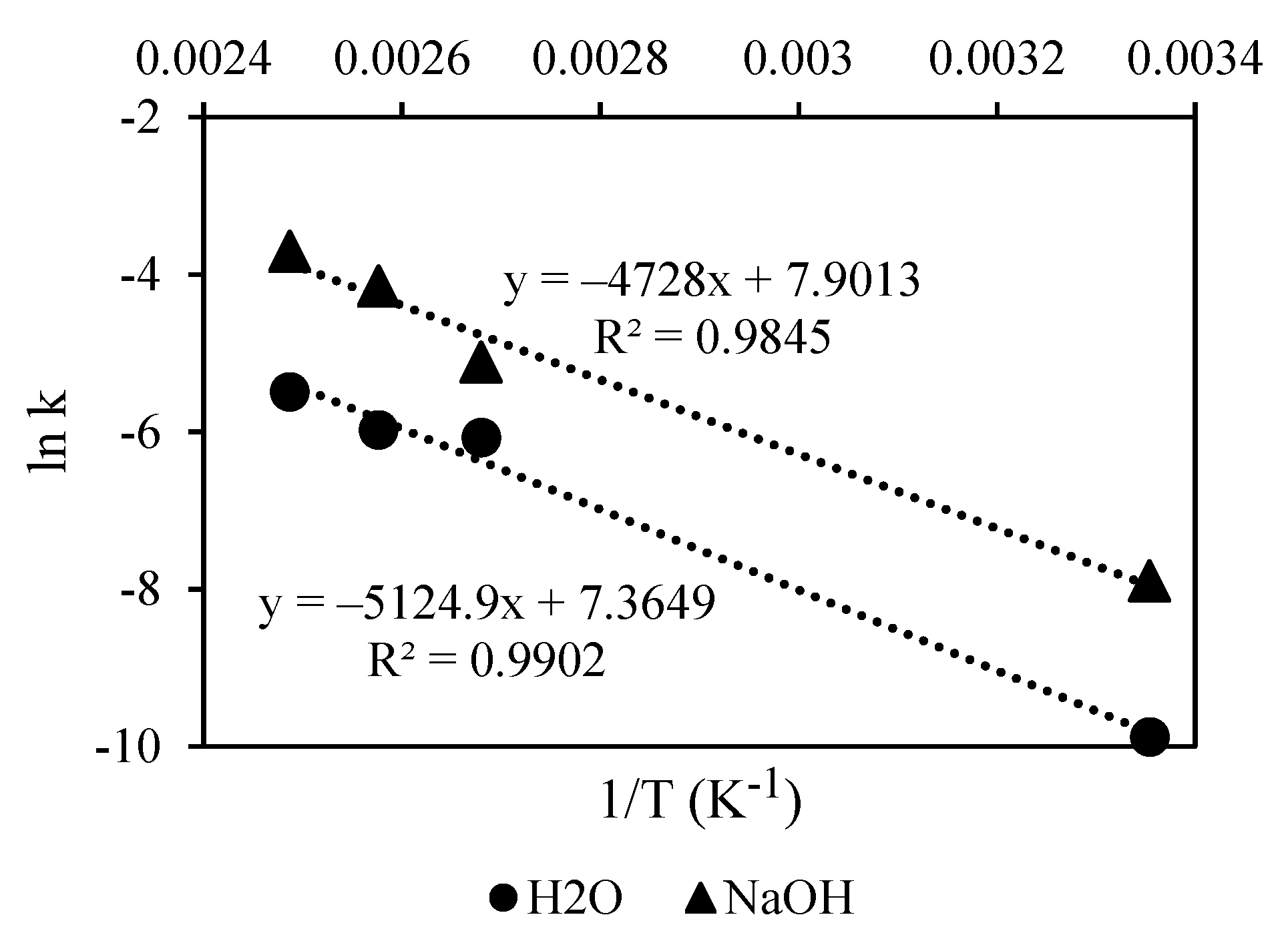

2.4. Lignin Removal Kinetics

2.5. Enzymatic Hydrolysis

2.6. Reducing Sugar Analysis

3. Results

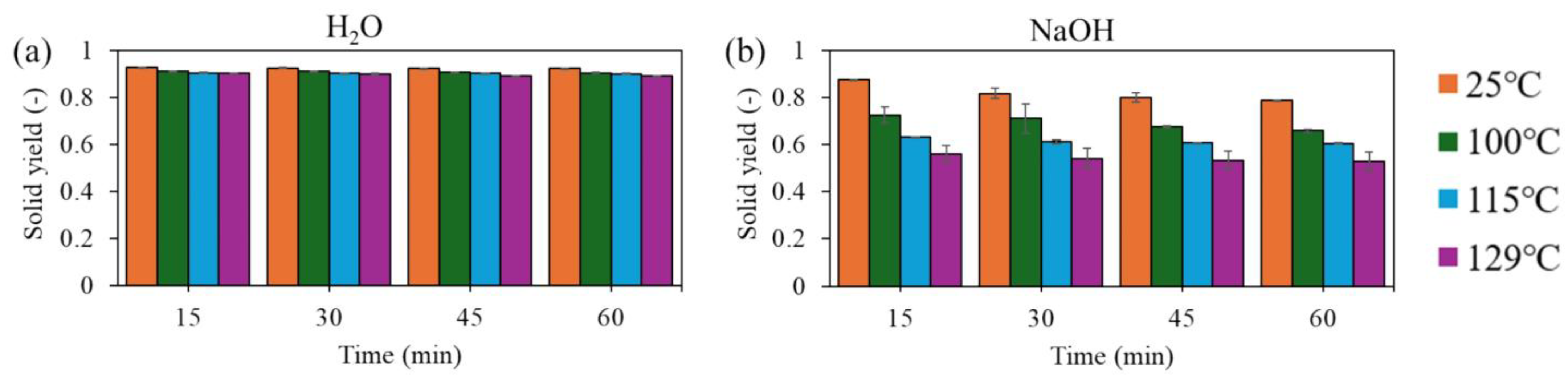

3.1. Solid Yield

3.2. Lignocellulose Composition and Effect of Temperature and Time

3.3. Lignin Removal

3.4. Delignification Kinetics

3.5. Enzymatic Hydrolysis: Effect of Hydrolysis Time and Pretreatment

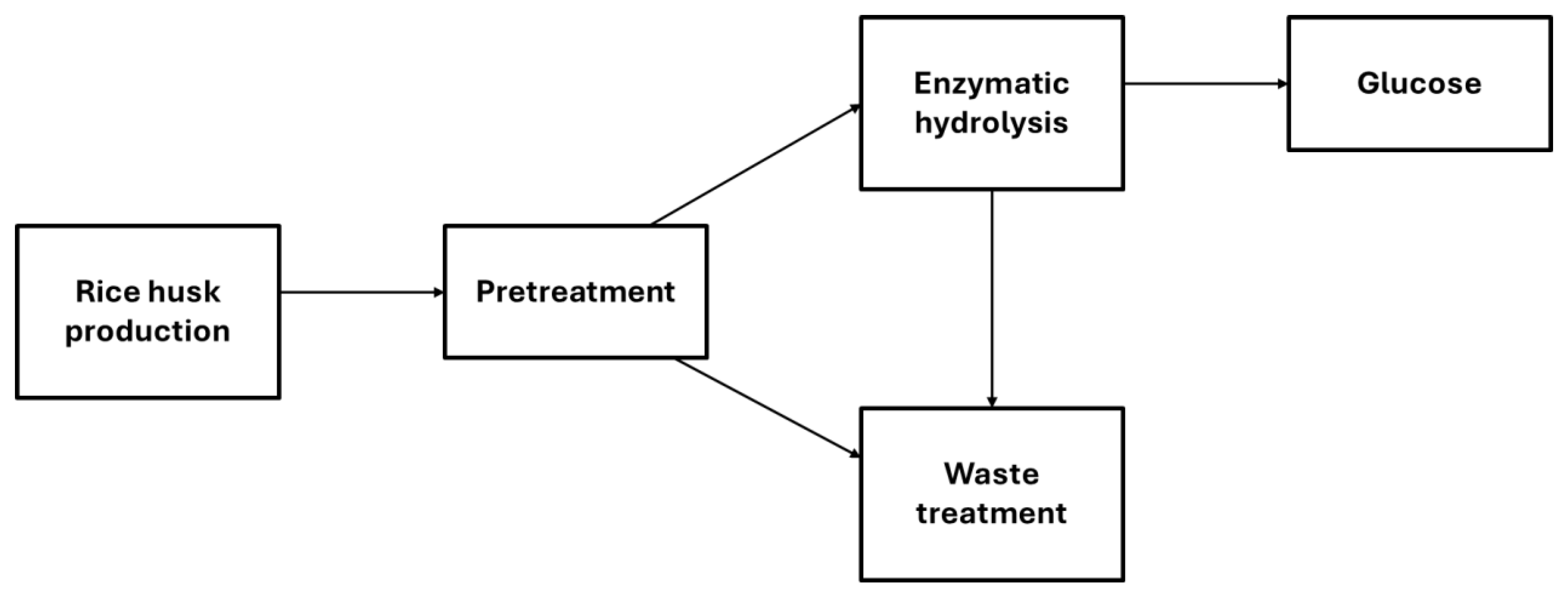

4. Life Cycle Assessment

4.1. Life Cycle Inventory Analysis

4.2. Life Cycle Impact Assessment

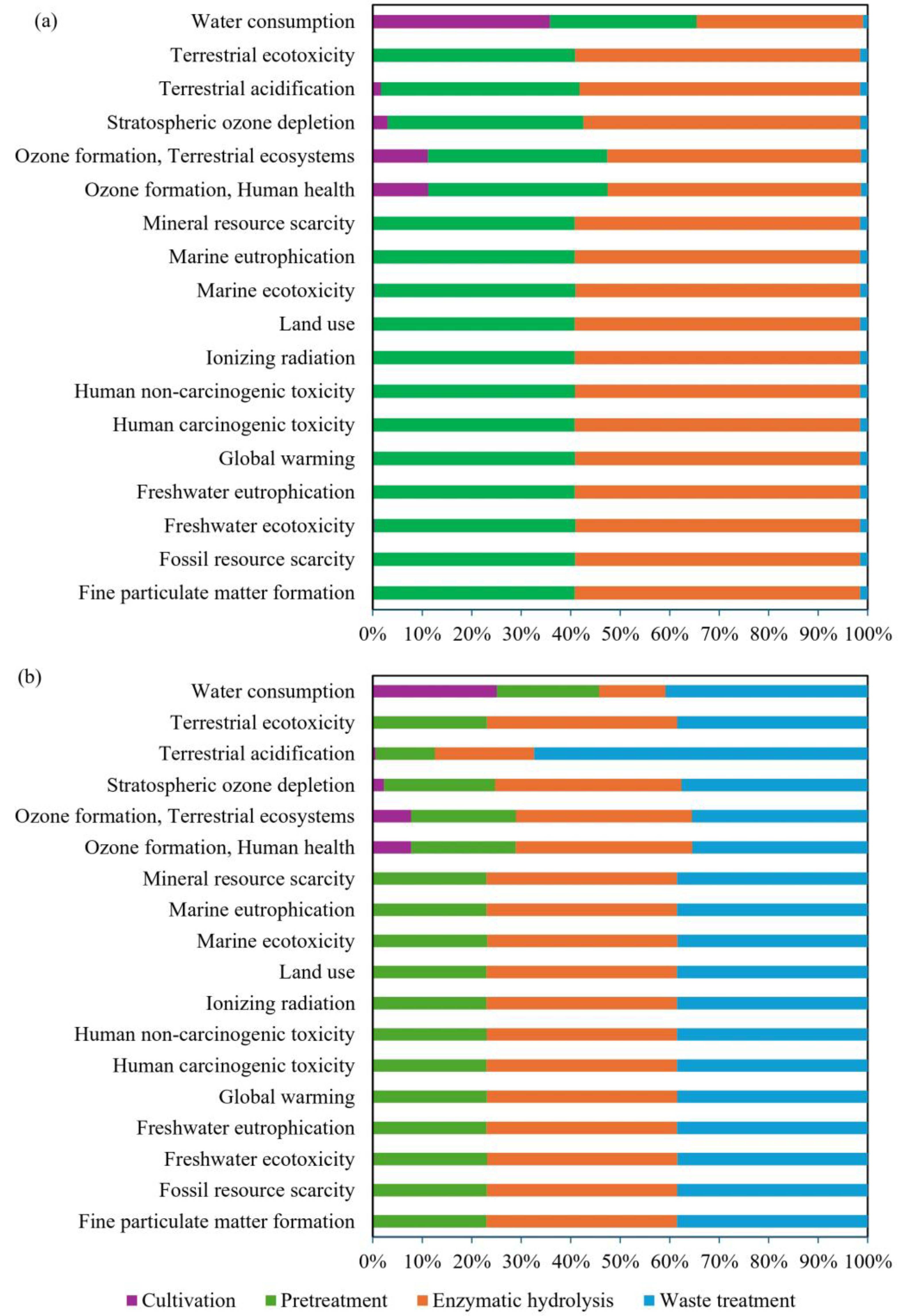

4.3. Process Contributions

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RH | Rice husk |

| LCA | Life cycle assessment |

| NaOH | Sodium hydroxide |

| H2O | Water |

| Ea | Activation energy |

References

- Ghosh, S.; Roy, S.; Das, P. Beyond Waste: Waste Rice Husk to Value-Added Products Using Sonic Waves and Chemical Treatment and Principal Component Analysis of Extraction. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 15, 11217–11229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannes, L.P.; Minh, T.T.N.; Van Son, N.; Tung, D.T.; Viet, T.D.; Xuan, T.D. Agronomic and Utilization Potential of Three Elephant Grass Cultivars for Energy, Forage, and Soil Improvement in Vietnam. Crops 2025, 5, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, E.; Miyamoto, T.; Kawamoto, H. Decomposition of Saccharides and Alcohols in Solution Plasma for Hydrogen Production. Hydrogen 2022, 3, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, P.K.; Patane, P.M. Biohydrogen: Advancing a Sustainable Transition from Fossil Fuels to Renewable Energy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 100, 955–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.; Sukri, S.; Yaacob, W. The Optimization of Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) Pre-Treatment for Reducing Sugar Production from Rice Husk Using Response Surface Methodology (RSM). ESTEEM Acad. J. 2024, 20, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, A.; Nikafshan Rad, H.; Akrami, M. Biomass-to-Green Hydrogen: A Review of Techno-Economic-Enviro Assessment of Various Production Methods. Hydrogen 2024, 5, 474–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukesh Kannah, R.; Kavitha, S.; Sivashanmugham, P.; Kumar, G.; Nguyen, D.D.; Chang, S.W.; Rajesh Banu, J. Biohydrogen Production from Rice Straw: Effect of Combinative Pretreatment, Modelling Assessment and Energy Balance Consideration. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 2203–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanis, M.H.; Wallberg, O.; Galbe, M.; Al-Rudainy, B. Lignin Extraction by Using Two-Step Fractionation: A Review. Molecules 2024, 29, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, D.; Nuruddin, M.; Hosur, M.; Tcherbi-Narteh, A.; Jeelani, S. Extraction and Characterization of Lignin from Different Biomass Resources. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2015, 4, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Greco, A.; Rajabimashhadi, Z.; Esposito Corcione, C. Efficient and Environmentally Friendly Techniques for Extracting Lignin from Lignocellulose Biomass and Subsequent Uses: A Review. Clean. Mater. 2024, 13, 100253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H.; Nižetić, S.; Sirohi, R.; Huang, Z.; Luque, R.; Papadopoulos, A.M.; Sakthivel, R.; Phuong Nguyen, X.; Tuan Hoang, A. Liquid Hot Water as Sustainable Biomass Pretreatment Technique for Bioenergy Production: A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, R.; Bhattacharya, D.; Mukhopadhyay, M. Enhanced Production of Biohydrogen from Lignocellulosic Feedstocks Using Microorganisms: A Comprehensive Review. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2022, 13, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjulander, N.; Kikas, T. Two-Step Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass for High-Sugar Recovery from the Structural Plant Polymers Cellulose and Hemicellulose. Energies 2022, 15, 8898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, C.; Wang, L.; Liu, G.; Ogunbiyi, A.T.; Li, W. The Catalytic Valorization of Lignin from Biomass for the Production of Liquid Fuels. Energies 2025, 18, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, Z.; Sharma-Shivappa, R.; Cheng, J. Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Switchgrass and Coastal Bermuda Grass Pretreated Using Different Chemical Methods. Bioresources 2011, 6, 2990–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliana, C.; Jorge, R.; Juan, P.; Luis, R. Effects of the Pretreatment Method on Enzymatic Hydrolysis and Ethanol Fermentability of the Cellulosic Fraction from Elephant Grass. Fuel 2014, 118, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannes, L.P.; Xuan, T.D. Comparative Analysis of Acidic and Alkaline Pretreatment Techniques for Bioethanol Production from Perennial Grasses. Energies 2024, 17, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.H.; Lee, W.C.; Kuan, W.C.; Sirisansaneeyakul, S.; Savarajara, A. Evaluation of Different Pretreatments of Napier Grass for Enzymatic Saccharification and Ethanol Production. Energy Sci. Eng. 2018, 6, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriez, V.; Peydecastaing, J.; Pontalier, P.Y. Lignocellulosic Biomass Mild Alkaline Fractionation and Resulting Extract Purification Processes: Conditions, Yields, and Purities. Clean Technol. 2020, 2, 91–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Beltrán, J.U.; Hernández-De Lira, I.O.; Cruz-Santos, M.M.; Saucedo-Luevanos, A.; Hernández-Terán, F.; Balagurusamy, N. Insight into Pretreatment Methods of Lignocellulosic Biomass to Increase Biogas Yield: Current State, Challenges, and Opportunities. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Lee, Y.Y.; Kim, T.H. A Review on Alkaline Pretreatment Technology for Bioconversion of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 199, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Cheng, J.-R.; Wang, Y.T.; Zhu, M.J. Enhanced Lignin Removal and Enzymolysis Efficiency of Grass Waste by Hydrogen Peroxide Synergized Dilute Alkali Pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 301, 122756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.S.; Therasme, O.; Volk, T.A.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, D. Optimization of Combined Hydrothermal and Mechanical Refining Pretreatment of Forest Residue Biomass for Maximum Sugar Release during Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Energies 2024, 17, 4929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novia, N.; Hasanudin, H.; Hermansyah, H.; Fudholi, A. Kinetics of Lignin Removal from Rice Husk Using Hydrogen Peroxide and Combined Hydrogen Peroxide and Combined Hydrogen Peroxide–Aqueous Ammonia Pretreatments. Fermentation 2022, 8, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermansyah, H.; Cahyadi, H.; Fatma, F.; Miksusanti, M.; Kasmiarti, G.; Panagan, A.T. Delignification of Lignocellulosic Biomass Sugarcane Bagasse by Using Ozone as Initial Step to Produce Bioethanol. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 30, 4405–4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, R. Acidogenic Fermentation of Lignocellulose–Acid Yield and Conversion of Components. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1981, 23, 2167–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baksi, S.; Sarkar, U.; Saha, S.; Ball, A.K.; Chandra Kuniyal, J.; Wentzel, A.; Birgen, C.; Preisig, H.A.; Wittgens, B.; Markussen, S. Studies on Delignification and Inhibitory Enzyme Kinetics of Alkaline Peroxide Pre-Treated Pine and Deodar Saw Dust. Chem. Eng. Process.—Process Intensif. 2019, 143, 107607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeni, A.O.; Omoleye, J.A.; Hymore, F.K.; Pandey, R.A. Effective Alkaline Peroxide Oxidation Pretreatment of Shea Tree Sawdust for the Production of Biofuels: Kinetics of Delignification and Enzymatic Conversion to Sugar and Subsequent Production of Ethanol by Fermentation Using Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 33, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Neogi, S.; Chakraborty, S. Experimental and Kinetic Analyses of Delignification of Lignocellulosic Grass with Minimal Holocellulose Loss during Pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2023, 23, 101549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Huang, C.; Lai, C.; Yong, Q. Liquid Hot Water Pretreatment Technology: Opening a New Chapter in the Green Transformation and High-Value Utilization of Biomass Resources. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 203, 108278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmeekong, A.; Chuenchom, L.; Charnnok, B.; Chaiprapat, S. Sustainable Valorization of Grass Biomass via Hydrothermal Pretreatment for Biogas and Biofuel Co-Production. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 389, 126109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergara, P.; Ladero, M.; García-Ochoa, F.; Villar, J.C. Pre-Treatment of Corn Stover, Cynara Cardunculus L. Stems and Wheat Straw by Ethanol-Water and Diluted Sulfuric Acid: Comparison under Different Energy Input Conditions. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 270, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.; Yang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Jia, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhou, C.; Yong, Q. Promoting Enzymatic Saccharification of Organosolv-Pretreated Poplar Sawdust by Saponin-Rich Tea Seed Waste. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 43, 1999–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Tran, N.T.; Phan, T.P.; Nguyen, A.T.; Nguyen, M.X.T.; Nguyen, N.N.; Ko, Y.H.; Nguyen, D.H.; Van, T.T.T.; Hoang, D. The Extraction of Lignocelluloses and Silica from Rice Husk Using a Single Biorefinery Process and Their Characteristics. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2022, 108, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabazuddin, M.; Sarat Chandra, T.; Meena, S.; Sukumaran, R.K.; Shetty, N.P.; Mudliar, S.N. Thermal Assisted Alkaline Pretreatment of Rice Husk for Enhanced Biomass Deconstruction and Enzymatic Saccharification: Physico-Chemical and Structural Characterization. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 263, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modenbach, A.A.; Nokes, S. Effects of Sodium Hydroxide Pretreatment on Structural Components of Biomass. Trans. ASABE 2014, 57, 1187–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, Y.W.; Tao, Q.; Akien, G.R.; Yuen, A.K.L.; Montoya, A.; Chan, B.; Lui, M.Y. Hydrothermal Depolymerization of Different Lignins: Insights into Structures and Reactivities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 314, 144293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannigrahi, P.; Pu, Y.; Ragauskas, A. Cellulosic Biorefineries—Unleashing Lignin Opportunities. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2010, 2, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Zeng, H.; Liu, B.; Zhu, J.; Wang, F.; Wang, S.; Liang, C.; Huang, C.; Ma, J.; Yao, S. Efficient Removal of Residual Lignin from Eucalyptus Pulp via High-Concentration Chlorine Dioxide Treatment and Its Effect on the Properties of Residual Solids. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 360, 127621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagnino, E.P.; Felissia, F.E.; Chamorro, E.; Area, M.C. Studies on Lignin Extraction from Rice Husk by a Soda-Ethanol Treatment: Kinetics, Separation, and Characterization of Products. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2018, 129, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Yang, X.; Wan, J.; He, Y.; Chang, C.; Ma, X.; Bai, J. Delignification Kinetics of Corn Stover with Aqueous Ammonia Soaking Pretreatment. Bioresources 2016, 11, 2403–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.J.; Wen, J.L.; Mei, Q.-Q.; Chen, X.; Sun, D.; Yuan, T.-Q.; Sun, R.-C. Facile Fractionation of Lignocelluloses by Biomass-Derived Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) Pretreatment for Cellulose Enzymatic Hydrolysis and Lignin Valorization. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiri, A.P.; Stamatakis, E.; Bellas, S.; Zoulias, M.; Mitkidis, G.; Anastasiadis, A.G.; Karellas, S.; Tzamalis, G.; Stubos, A.; Tsoutsos, T. A Review of Alternative Processes for Green Hydrogen Production Focused on Generating Hydrogen from Biomass. Hydrogen 2024, 5, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litti, Y.V.; Kovalev, A.A.; Kovalev, D.A.; Katraeva, I.V.; Parshina, S.N.; Zhuravleva, E.A.; Botchkova, E.A. Characteristics of the Process of Biohydrogen Production from Simple and Complex Substrates with Different Biopolymer Composition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 26289–26297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Armijos, J.; Lapo, B.; Beltrán, C.; Sigüenza, J.; Madrid, B.; Chérrez, E.; Bravo, V.; Sanmartín, D. Effect of Alkaline and Hydrothermal Pretreatments in Sugars and Ethanol Production from Rice Husk Waste. Resources 2024, 13, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuradha, A.; Sampath, M.K. Process Optimization for the Pretreatment of Rice Husk with Deep Eutectic Solvent for Efficient Sugar Production. Environ. Technol. 2024, 45, 3807–3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, E.; Rios, J.; Peña, J.; Peñuela, M.; Rios, L. King Grass: A Very Promising Material for the Production of Second Generation Ethanol in Tropical Countries. Biomass Bioenergy 2016, 95, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Zhu, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, D.; Yang, W.; Xu, H. High Pressure Assist-Alkali Pretreatment of Cotton Stalk and Physiochemical Characterization of Biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 148, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, D.P.M.; Capaz, R.S. A Review of the Life Cycle Assessment of the Carbon–Water–Energy Nexus of Hydrogen Production Pathways. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, H.; Yuan, Z.; Li, X.; Wu, M.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z. Application of Pretreatment Methods and Life Cycle Assessment in the Production of Wood Vinegar Substitutes via Hydrothermal Oxidation of Cotton Stalks. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 232, 121238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hung, N.; Migo, M.V.; Quilloy, R.; Chivenge, P.; Gummert, M. Life Cycle Assessment Applied in Rice Production and Residue Management. In Sustainable Rice Straw Management; Gummert, M., Van Hung, N., Chivenge, P., Douthwaite, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 161–174. ISBN 978-3-030-32373-8. [Google Scholar]

- Blengini, G.A.; Busto, M. The Life Cycle of Rice: LCA of Alternative Agri-Food Chain Management Systems in Vercelli (Italy). J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1512–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhashim, R.; Deepa, R.; Anandhi, A. Environmental Impact Assessment of Agricultural Production Using LCA: A Review. Climate 2021, 9, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Yang, L.; Liang, X.; Zhou, J. Utilizing Life Cycle Assessment to Optimize Processes and Identify Emission Reduction Potential in Rice Husk-Derived Nanosilica Production. Processes 2025, 13, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, T.; Huhe, T.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Lei, T.; Zhou, Z. Research on Life Cycle Assessment and Performance Comparison of Bioethanol Production from Various Biomass Feedstocks. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Rahman, M.H.; Chen, S.S.; Abdul Razak, P.R.; Abu Bakar, N.A.; Shahrun, M.S.; Zin Zawawi, N.; Muhamad Mujab, A.A.; Abdullah, F.; Jumat, F.; Kamaruzaman, R.; et al. Life Cycle Assessment in Conventional Rice Farming System: Estimation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions Using Cradle-to-Gate Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 1526–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Sotenko, M.; Blenkinsopp, T.; Coles, S.R. Life Cycle Assessment of Lignocellulosic Biomass Pretreatment Methods in Biofuel Production. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Bakar, N.A.; Roslan, A.M.; Hassan, M.A.; Rahman, M.H.A.; Ibrahim, K.N.; Abd Rahman, M.D.; Mohamad, R. Environmental Impact Assessment of Rice Mill Waste Valorisation to Glucose through Biorefinery Platform. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, K.; Rehan, M.; Nizami, A.-S. Optimizing Bioethanol Production by Comparative Environmental and Economic Assessments of Multiple Agricultural Feedstocks. Processes 2025, 13, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madu, J.O.; Agboola, B.O. Bioethanol Production from Rice Husk Using Different Pretreatments and Fermentation Conditions. 3 Biotech 2017, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Tokuyasu, K.; Orisaka, T.; Nakamura, N.; Shina, T. A Review of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Bioethanol from Lignocellulosic Biomass. Jpn. Agric. Res. Q. JARQ 2012, 46, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Xiros, C.; Tillman, A.-M. Life Cycle Impacts of Ethanol Production from Spruce Wood Chips under High-Gravity Conditions. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2016, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, J.; Iglesias, J.; Morales, G.; Melero, J.A.; Moreno, J. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Glucose Production from Maize Starch and Woody Biomass Residues as a Feedstock. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| H2O | NaOH | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | k | Ea (kJ mol−1 K−1) | R2 | Temperature (°C) | k | Ea (kJ mol−1 K−1) | R2 |

| 25 | 5.14 × 10−5 | 42.61 | 0.99 | 25 | 3.73 × 10−4 | 39.31 | 0.97 |

| 100 | 2.31 × 10−3 | 0.97 | 100 | 6.00 × 10−3 | 0.92 | ||

| 115 | 2.55 × 10−3 | 0.97 | 115 | 1.58 × 10−2 | 0.90 | ||

| 129 | 4.13 × 10−3 | 0.99 | 129 | 2.46 × 10−2 | 0.96 | ||

| Biomass | Pretreatment | Activation Energy (kJ mol−1K−1) | Reference |

| RH | Water 25–129 °C | 42.76 | This study |

| RH | 3% NaOH 25–129 °C | 39.31 | This study |

| RH | Hydrogen peroxide and combined hydrogen peroxide and ammonia 30–80 °C | 13.68 8.18 | [24] |

| Sawdust | Alkaline hydrogen peroxide temperature 30–100 °C. 1–5 h | 18.71 | [27] |

| RH | Soda ethanol treatment. 140–160 °C | 33.47–38.59 | [34] |

| Shea tree | Hydrogen peroxide 120–150 °C | 76.40 | [28] |

| Corn stover | Ammonia 30–70 °C | 61.05 | [35] |

| Process/Flow | Flow Type | Unit | Input | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process 1: Cultivation | ||||

| Nitrogen fertilizer | Product | kg | 3.41 × 10−2 | |

| Phosphorous fertilizer | Product | kg | 1.30 × 10−2 | |

| Potassium fertilizer | Product | kg | 1.31 × 10−2 | |

| Water | Resource | kg | 18.00 | |

| Transport, freight | Product | t × km | 1 × 10−3 × 100 | |

| RH | Product | kg | 1.00 | |

| Methane | Elementary | kg | 0.08 | |

| Nitrous oxide | Elementary | kg | 7.11 × 10−4 | |

| Process 2: Pretreatment | ||||

| RH | Product | kg | 41.16 | |

| Electricity (heating) | Product | kwh | 83.61 | |

| Water | Product | kg | 675.00 | |

| Electricity (grinding) | Product | kwh | 1.44 | |

| Pretreated RH | Product | kg | 37.04 | |

| Wastewater | Product | kg | 575.00 | |

| Water (vapor) | Elementary | kg | 100.00 | |

| Process 3: Enzymatic hydrolysis | ||||

| Pretreated RH | Product | kg | 37.00 | |

| Cellulase enzyme | Product | kg | 11.10 | |

| Citric acid | Product | kg | 5.07 × 10−3 | |

| Trisodium citrate | Product | kg | 5.55 × 10−3 | |

| Water | Product | kg | 703.00 | |

| Electricity | Product | kwh | 48.00 | |

| Glucose | Product | kg | 1.00 | |

| Hydrolysis residue | Product | kg | 29.6 | |

| COD | Elementary | kg | 0.03 | |

| Wastewater | Elementary | kg | 492.11 | |

| Water | Elementary | kg | 210.90 | |

| CO2 | Elementary | kg | 3.70 | |

| Process 4: Waste treatment | ||||

| Wastewater | Product | kg | 492.10 | |

| Hydrolysis residue | Product | kg | 29.60 | |

| Sludge | Waste | kg | 521.70 | |

| CO2 | Elementary | kg | 0.30 | |

| Water | Waste | kg | 492.10 |

| Process/Flow | Flow Type | Unit | Input | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process 1: Cultivation | ||||

| Nitrogen fertilizer | Product | kg | 3.41 × 10−2 | |

| Phosphorous fertilizer | Product | kg | 1.30 × 10−2 | |

| Potassium fertilizer | Product | kg | 1.31 × 10−2 | |

| Water | Product | kg | 50.00 | |

| Transport, freight | Product | t ×km | 1 × 10−3 × 100 | |

| RH | Product | kg | 1.00 | |

| Methane | Elementary | kg | 0.08 | |

| Nitrous oxide | Elementary | kg | 7.11 × 10−3 | |

| Process 2: Pretreatment | ||||

| RH | Product | kg | 34.00 | |

| Water | Product | kg | 510.00 | |

| Electricity (drying) | Product | kwh | 63.35 | |

| Electricity (grinding) | Product | kwh | 1.44 | |

| NaOH | Product | kg | 15.30 | |

| Pretreated RH | Product | kg | 20.00 | |

| Wastewater black liquor | Elementary | kg | 410.00 | |

| CO2 | Elementary | kg | 0.58 | |

| Sodium ion | Elementary | kg | 0.30 | |

| Water (vapor) | Elementary | kg | 100.00 | |

| Process 3: Enzymatic hydrolysis | ||||

| Pretreated RH | Product | kg | 20.00 | |

| Cellulase enzyme | Product | kg | 6.00 | |

| Citric acid | Product | kg | 2.74 × 10−3 | |

| Trisodium citrate | Product | kg | 3 × 10−3 | |

| Water (citrate buffer) | Product | kg | 380.00 | |

| Electricity | Product | kwh | 48.00 | |

| Glucose | Product | kg | 1.00 | |

| Hydrolysis residue | Product | kg | 16.00 | |

| COD | Elementary | kg | 5.20 × 10−2 | |

| Wastewater | Elementary | kg | 266.00 | |

| Water (loss to air) | Elementary | kg | 114.00 | |

| Process 4: Waste treatment | Product | |||

| Wastewater black liquor | Product | kg | 266.00 | |

| Hydrolysis residue | Product | kg | 16.00 | |

| Sulfuric acid | Product | kg | 8.00 | |

| Water | product | kg | 798.00 | |

| Sludge | Waste | kg | 282.00 | |

| CO2 | Elementary | kg | 6.00 | |

| Sodium sulfate | Elementary | kg | 14.00 | |

| Water | Waste | kg | 1064.00 |

| No. | Impact Category | Reference Unit | H2O Pretreatment | NaOH Pretreatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fine particulate matter formation | kg PM2.5 eq | 4.42 × 10−2 | 5.95 × 10−2 |

| 2 | Fossil resource scarcity | kg oil eq | 240.03 | 323.28 |

| 3 | Freshwater ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 4.83 × 10−2 | 6.51 × 10−2 |

| 4 | Freshwater eutrophication | kg P eq | 3.51 × 10−3 | 4.72 × 10−3 |

| 5 | Global warming | kg CO2 eq | 1056.73 | 1423.64 |

| 6 | Human carcinogenic toxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 2.43 × 10−1 | 3.27 × 10−1 |

| 7 | Human non-carcinogenic toxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 7.95 | 10.71 |

| 8 | Ionizing radiation | kBq Co-60 eq | 33.05 | 44.53 |

| 9 | Land use | m2a crop eq | 1.00 × 10−1 | 1.35 × 10−1 |

| 10 | Marine ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 1.08 × 10−1 | 1.45 × 10−1 |

| 11 | Marine eutrophication | kg N eq | 1.72 × 10−2 | 2.32 × 10−2 |

| 12 | Mineral resource scarcity | kg Cu eq | 9.04 × 10−2 | 1.22 × 10−1 |

| 13 | Ozone formation human health | kg NOx eq | 1.57 | 2.04 |

| 14 | Ozone formation terrestrial ecosystems | kg NOx eq | 1.58 | 2.05 |

| 15 | Stratospheric ozone depletion | kg CFC-11 eq | 1.05 × 10−4 | 1.40 × 10−4 |

| 16 | Terrestrial acidification | kg SO2 eq | 4.01 | 10.20 |

| 17 | Terrestrial ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 234.78 | 316.23 |

| 18 | Water consumption | m3 | 2.09 | 2.66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Johannes, L.P.; Thinh, N.V.; Hasan, M.S.; Hai Anh, N.T.; Xuan, T.D. Delignification of Rice Husk for Biohydrogen-Oriented Glucose Production: Kinetic Analysis and Life Cycle Assessment of Water and NaOH Pretreatments. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040121

Johannes LP, Thinh NV, Hasan MS, Hai Anh NT, Xuan TD. Delignification of Rice Husk for Biohydrogen-Oriented Glucose Production: Kinetic Analysis and Life Cycle Assessment of Water and NaOH Pretreatments. Hydrogen. 2025; 6(4):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040121

Chicago/Turabian StyleJohannes, Lovisa Panduleni, Nguyen Van Thinh, Md Sahed Hasan, Nguyen Thi Hai Anh, and Tran Dang Xuan. 2025. "Delignification of Rice Husk for Biohydrogen-Oriented Glucose Production: Kinetic Analysis and Life Cycle Assessment of Water and NaOH Pretreatments" Hydrogen 6, no. 4: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040121

APA StyleJohannes, L. P., Thinh, N. V., Hasan, M. S., Hai Anh, N. T., & Xuan, T. D. (2025). Delignification of Rice Husk for Biohydrogen-Oriented Glucose Production: Kinetic Analysis and Life Cycle Assessment of Water and NaOH Pretreatments. Hydrogen, 6(4), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040121