1. Introduction

Green and sustainable hydrogen increasingly underpins Europe’s quest for energy sector decarbonisation. Yet, its successful integration in the new European energy system framework depends heavily on matching supply capabilities with reliable, large-scale storage availability. The European Union’s (EU) Hydrogen Strategy emphasises that hydrogen stands as a key component for the EU’s energy transition towards carbon neutrality and sustainable development [

1]. Still, REPowerEU and the security resilience framework highlight the need to reduce fossil gas dependency and rapidly scale alternative energy systems, especially those related to the green hydrogen domain [

2]. Such strategic framing underscores the criticality of storage for ensuring resilience, decoupling supply from demand, and stabilising variable renewable energy generation.

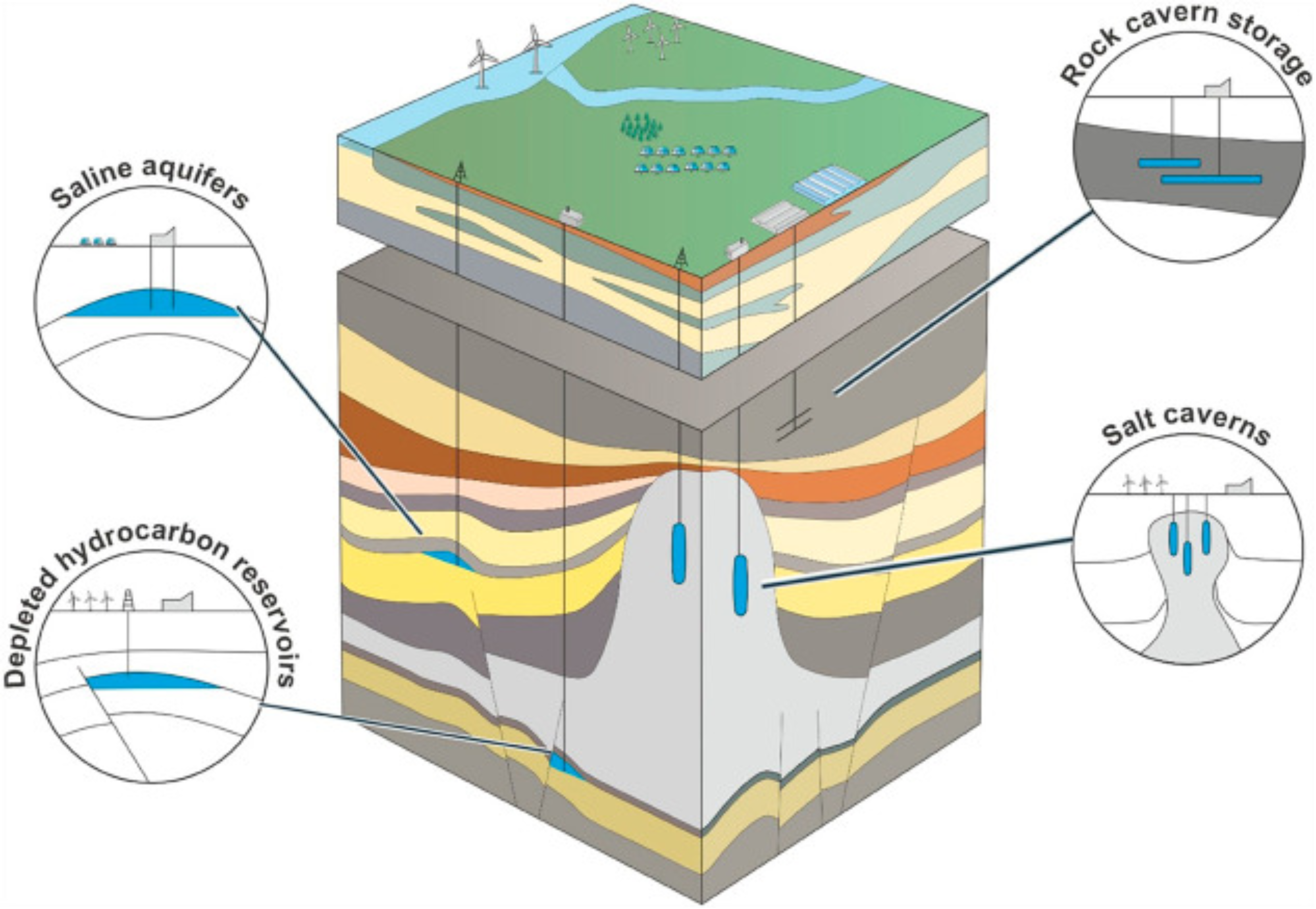

While on-ground storage and certain types of underground storage (see

Figure 1) like salt caverns and depleted hydrocarbon reservoirs have drawn considerable attention as a proven and well-known set of storage technologies [

3], aquifers remain a comparatively underexplored avenue with significant potential. From a technical point of view, geological suitability, including porosity, permeability, and caprock integrity, alone cannot determine whether a formation can safely and efficiently retain hydrogen at the necessary pressure regime of up to 100 bar. This is because this same porosity in aquifers can come up as a source of challenges linked to the fact that hydrogen may dissolve into brine and migrate via diffusion or microfractures, unless caprock quality and reservoir sealing systems are validated.

Beyond geology, hybrid criteria such as cost, geographic distribution, and integration of aquifer hydrogen gas storage into existing energy value chains and smart energy systems play a pivotal role [

5]. For instance, salt caverns, which are renowned for their impermeability, are geographically limited [

6], whereas aquifers are often closer to production centres or industrial demand zones. This makes aquifer storage, in principle, more scalable within a decentralised hydrogen infrastructure.

However, substantial risks and uncertainties persist. Hydrogen’s chemical reactivity, especially in brine-rich, biologically active aquifers, may induce microbial conversion, raising concerns about gas purity, pressure loss, and storage’s long-term viability. Moreover, aquifers differ geologically from region to region, demanding thorough site-specific analysis before deployment of a full-scale hydrogen storage project. There are 61 active aquifer storages for natural gas/biomethane in five out of eight Baltic Sea region countries: Germany, Poland, Denmark, Sweden and Latvia. In Finland, like in Lithuania and Estonia, there are no specific geological conditions to develop large-scale aquifer storage. From the rest of Baltic Sea region countries, the largest number of active aquifer storages is located in Germany—50. The second biggest number of active aquifer storages is in Poland—7, followed by Denmark with 2 and Sweden and Latvia with 1 active aquifer storage [

7]. None of these storages is tested for hydrogen and methane-based gas co-storage or replacement of active methane-based gas with hydrogen. At the same time, however, several EU projects provide real-world examples relevant to adaptation of aquifer storages to hydrogen. The HyUSPRe project [

8] is developing a saline-aquifer pilot for hydrogen storage and offers detailed data on reservoir characterization, cushion-gas management, and monitoring systems. The Hystories initiative [

9] investigates seasonal geological hydrogen storage solutions across Europe, enabling system-level comparisons and integration of storage into hydrogen value chains. Meanwhile, HyUnder [

10] gathers mapping of subsurface hydrogen storage potential, regulatory and monitoring frameworks, and stakeholder engagement practices across the EU, thereby supporting the deployment pathways evaluated in this work. Reference to these projects grounds the present techno-economic modelling in operational and policy-relevant contexts. Policy and regulatory frameworks are also influencing hydrogen storage choices. While the EU’s Hydrogen and Decarbonised Gas Market Package is moving toward unified infrastructure and certification standards [

11], current legal frameworks across the Member States remain tethered to norms of the methane-based gases.

The goal of this research is to evaluate the feasibility and technical requirements for utilising aquifers as large-scale hydrogen storage systems, and to develop a scientifically grounded technical design layout that addresses both subsurface and surface infrastructure needs. The study aims to support the strategic deployment of aquifer-based hydrogen storage in the context of Europe’s renewable energy integration and decarbonisation objectives. Hypothesis of the research is formulated as follows: if aquifers with adequate sealing and structural characteristics are equipped with hydrogen-compatible infrastructure and guided by optimised technical design principles, then they can serve as safe, scalable, and economically viable underground hydrogen storage sites comparable to or surpassing other storage modalities in strategic value.

Research questions are formulated as follows:

RQ1 What geological and geochemical criteria determine the suitability of a water-bearing porous formation for hydrogen storage?

RQ2 What are the main technical and operational risks associated with hydrogen storage in aquifers, and how can they be mitigated?

RQ3 What infrastructure components (both subsurface and surface) are essential for the safe and efficient design of a hydrogen aquifer storage system?

RQ4 How economically feasible is large-scale hydrogen storage in aquifers under current and future market conditions?

RQ5 What role do aquifer hydrogen storage systems play in supporting energy transition objectives compared to other underground storage options?

Research design-wise, the study begins with a review of existing literature on underground gas storage, hydrogen behaviour in porous media, and aquifer characterisation. This phase establishes the theoretical foundation and identifies critical knowledge gaps related to hydrogen solubility, microbial risks, caprock integrity, and cushion gas strategies. Key parameters from previous natural gas storage projects are compared and extrapolated for hydrogen use cases. Using geological, hydrogeological, and geochemical benchmarks, the study defines the conditions necessary for a formation to qualify as a hydrogen storage site. Criteria include depth, porosity, permeability, structural trapping, caprock sealing capacity, and formation water chemistry. These criteria are then structured into a decision-making matrix suitable for integration into GIS-based site selection tools.

Based on the defined subsurface conditions, a comprehensive hydrogen-compatible infrastructure design is developed. This includes subsurface well configuration, surface compression and injection systems, dehydration units, gas monitoring arrays, SCADA-based control systems, and safety protocols. The design integrates hydrogen-specific risks such as embrittlement, leakage, microbial conversion, and high diffusivity.

A techno-economic model is constructed for a hypothetical storage facility with 1 BCM capacity. The model includes detailed CAPEX and OPEX calculations, sensitivity analysis, and a basic financial assessment using NPV and payback period metrics. Optimisation scenarios are developed to identify cost-saving strategies.

A strategic assessment is carried out through SWOT analysis to evaluate strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of aquifer storage in comparison with other storage technologies. Additionally, non-monetised benefits such as grid flexibility, decarbonisation support, and energy security are identified and discussed. This integrative research design ensures a holistic evaluation, balancing technical precision, economic rationale, and strategic context, while providing a blueprint for future demonstration and commercial-scale projects.

The novelty of the study lies in its integrated approach, which combines geological criteria, infrastructure design, microbial risk mitigation, and techno-economic modelling into a single coherent methodology. The study introduces a new design layout for subsurface and surface components centred around hydrogen’s distinct physical behaviour, including high diffusivity and low density, as well as its chemical reactivity with water, microbes, and steel. The study also quantifies hydrogen dissolution, microbial conversion, and cushion gas strategies using models adapted for hydrogen rather than methane. Furthermore, it presents one of the first comprehensive economic models applied specifically to aquifer-based hydrogen storage at the scale of 1 BCM, identifying the cost bottlenecks and potential optimisation strategies. Importantly, the study adds value through its sensitivity analysis, a feature often absents in early-stage conceptual assessments. It evaluates not only financial metrics like CAPEX and OPEX but also incorporates non-monetised system benefits such as grid balancing, decarbonisation impact, and strategic energy security. This holistic view enhances the applicability of the findings to policymakers, investors, and technical developers.

The study holds significant importance for potential energy crisis mitigation in Europe as well. By developing a comprehensive framework for hydrogen storage in aquifers, it directly addresses the vulnerability of the EU’s energy system to supply disruptions, market volatility, and geopolitical shocks [

12,

13]. Large-scale underground hydrogen storage provides a resilient energy reserve that can be rapidly mobilized during crises, ensuring the continuity of industrial operations, electricity generation, and heating supply. Aquifers, due to their widespread geographic distribution, allow energy reserves to be located closer to demand centres, reducing dependence on cross-border imports and critical infrastructure bottlenecks. The research also contributes to long-term energy diversification by offering a sustainable alternative to natural gas storage, enhancing Europe’s autonomy in times of disrupted fossil fuel supply. Its techno-economic modelling supports decision-making for crisis-resilient infrastructure investments. Moreover, by quantifying risks such as microbial conversion, leakage, and cushion gas losses, the study improves safety and operational readiness under emergency conditions. Overall, it strengthens the scientific and strategic basis for integrating aquifer-based hydrogen storage into the EU’s crisis response and energy security planning framework [

14].

The study, however, is limited by the absence of full-scale empirical field data from existing aquifer-based hydrogen storage facilities, as no commercial-scale projects have yet been commissioned. The analysis relies on analogues from natural gas storage and conceptual modelling rather than site-specific research. Furthermore, cost estimates and economic models are based on generalised market assumptions, which may not capture regional variability in infrastructure costs or regulatory barriers. Finally, environmental and social acceptance aspects are acknowledged but not quantitatively assessed in depth within the scope of this study.

The study begins with an Introduction, which outlines the research background, objectives, and the novelty of the study within the broader context of the EU’s energy transition and security goals. The Background Analysis then reviews the current state of knowledge, identifying key challenges and knowledge gaps related to geological, chemical, and microbial processes governing underground hydrogen storage. The

Section 3 present the integrated methodological approach, combining geological characterization, thermodynamic modelling, reactive transport simulations, and techno-economic assessment into a coherent workflow. The

Section 4 provides a detailed evaluation of technical risks, storage performance, and cost factors, supported by quantitative data and comparative analyses. This is followed by the

Section 6, which interprets the findings in relation to previous research and policy frameworks, emphasizing the implications for energy system resilience and crisis mitigation. Finally, the

Section 7 summarize the key outcomes, highlight the study’s contributions, and propose directions for future research and pilot-scale validation.

2. Background Analysis

According to [

13], reservoir depth plays a crucial role in determining hydrogen injectivity, storage capacity, and pressure stability in aquifer. Their simulations reveal that storage efficiency improves with depth up to approximately 1500 m, after which reservoir pressure and caprock constraints limit further gains. In a complementary study, ref. [

15] highlight the persistent challenge of non-recoverable cushion gas, estimating that 35–63% of injected hydrogen may remain trapped within the formation. Such findings underscore that hydrogen storage in aquifers is not merely a technical problem of injection and withdrawal but also a significant economic optimization task.

Comparative geological assessments also suggest that while salt caverns remain the most mature storage option, aquifers offer broader geographic availability and higher volumetric capacity [

16]. However, these formations pose greater uncertainty in containment and gas recovery. Ref. [

17] further demonstrates that monitoring deformation in fractured aquifers using free and open satellite data can effectively track reservoir pressure changes, providing a cost-effective integrity management tool.

At the pore scale, researchers have identified complex two-phase flow mechanisms that govern hydrogen–brine interactions. Ref. [

18] illustrates how capillary trapping and wettability determine hydrogen mobility and residual saturation in porous media. Similarly, ref. [

19] highlights the importance of interfacial tension and diffusion effects on containment integrity, recommending laboratory protocols for assessing leakage risk. These microscopic insights translate directly into reservoir-scale design, where well placement, injection pressure, and cushion gas composition become decisive parameters. Ref. [

20] shows that optimizing these factors can significantly improve hydrogen purity and recovery efficiency, proposing engineering strategies that reduce losses and contamination.

The integration of geological, technical, and sustainability considerations is further advanced by [

21], who develop a multi-criteria framework for assessing underground gas storage in multi-layered aquifers. Their model bridges geological risk assessment with economic feasibility and environmental safety, positioning aquifer storage within broader sustainable energy planning. On the biogeochemical front, ref. [

22] emphasizes microbial activity and mineral reactivity as key factors influencing long-term hydrogen stability in European aquifers. Their review suggests that microbial hydrogen consumption and mineral alteration could threaten storage integrity if not properly managed through reservoir conditioning and monitoring.

Taken together, these studies form a coherent picture of a field transitioning from conceptual exploration to practical engineering application. The consensus emerging across literature is that aquifer-based hydrogen storage, while technically feasible, requires a highly interdisciplinary approach, integrating reservoir physics, hydrogeology, microbiology, and economic analysis. The main research priorities now lie in minimizing cushion-gas losses, enhancing recovery efficiency, and ensuring long-term containment through improved modelling and monitoring. As Europe’s hydrogen infrastructure expands, the body of work reviewed here positions aquifer hydrogen storages as a viable, scalable, and increasingly mature component of the future clean energy system [

15,

17,

18,

22].

At the same time, hydrogen is increasingly recognised as a viable medium for long-term energy storage. While hydrogen on ground storage and salt caverns has been widely examined and analysed for hydrogen storage [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31] gained attention much later, mostly due to their large volumetric capacity and widespread availability [

32,

33]. The feasibility of hydrogen storage is drawn on operational analogies with natural gas storage [

34], yet the unique physical and chemical properties of hydrogen introduce novel challenges and opportunities [

5]. As shown in modelling studies like [

35], in aquifers, often composed of sandstones and bounded by impermeable rock caps, hydrogen storage is theoretically possible; however, its low molecular weight and high diffusivity make it more mobile than methane. For instance, hydrogen’s diffusivity in porous rock can be 2–10 times higher than methane, raising containment concerns [

36]. Moreover, due to its lower viscosity, hydrogen may migrate faster through caprock microfractures, increasing the risk of leakage [

37].

One of the additional, most critical concerns for hydrogen storage in aquifers is biological reactivity. Hydrogen can serve as an electron donor for anaerobic microbial communities, leading to conversion into methane or hydrogen sulfide (H

2S). As confirmed in a few laboratory-scale biogeochemical experiments, hydrogenotrophic methanogens and sulphate-reducing bacteria (SRB) can consume substantial amounts of hydrogen in sedimentary aquifers, potentially leading to energy loss and gas contamination [

38]. As shown in some research, in controlled tests, microbial communities converted up to 20% of the stored hydrogen to methane over six months, especially in formations with organic-rich brines. These transformations could compromise gas quality and increase infrastructure corrosion [

39].

Hydrogen’s solubility in the brine is another risk factor. Under typical storage conditions (60–100 bar, 30–600 °C), hydrogen dissolves in water at concentrations between 1.6 and 2.5 mg/L. Unlike methane, hydrogen has a higher solubility in saline water, leading to diffusion into the aqueous phase and loss from the recoverable gas volume [

40]. This effect is particularly relevant for long-term storage cycles. Reactive transport modelling (RTM) results show that up to 5–15% of injected hydrogen could be lost to dissolution and diffusion per cycle, especially in formations with high groundwater flow velocities [

41,

42].

Caprock integrity, again, is another cornerstone of secure underground storage. Hydrogen’s high mobility raises concerns about microseepage through caprocks and along wellbores. Studies using capillary entry pressure testing and micro-CT scanning show that even low-permeability shales may not fully restrict hydrogen migration over multi-year periods [

40]. Furthermore, abandoned wells, if inadequately sealed, can act as pathways for hydrogen escape, as was observed in old gas storage fields repurposed for hydrogen pilot studies in Germany. Leakage along abandoned wells remains one of the highest risks for aquifer-based hydrogen storage [

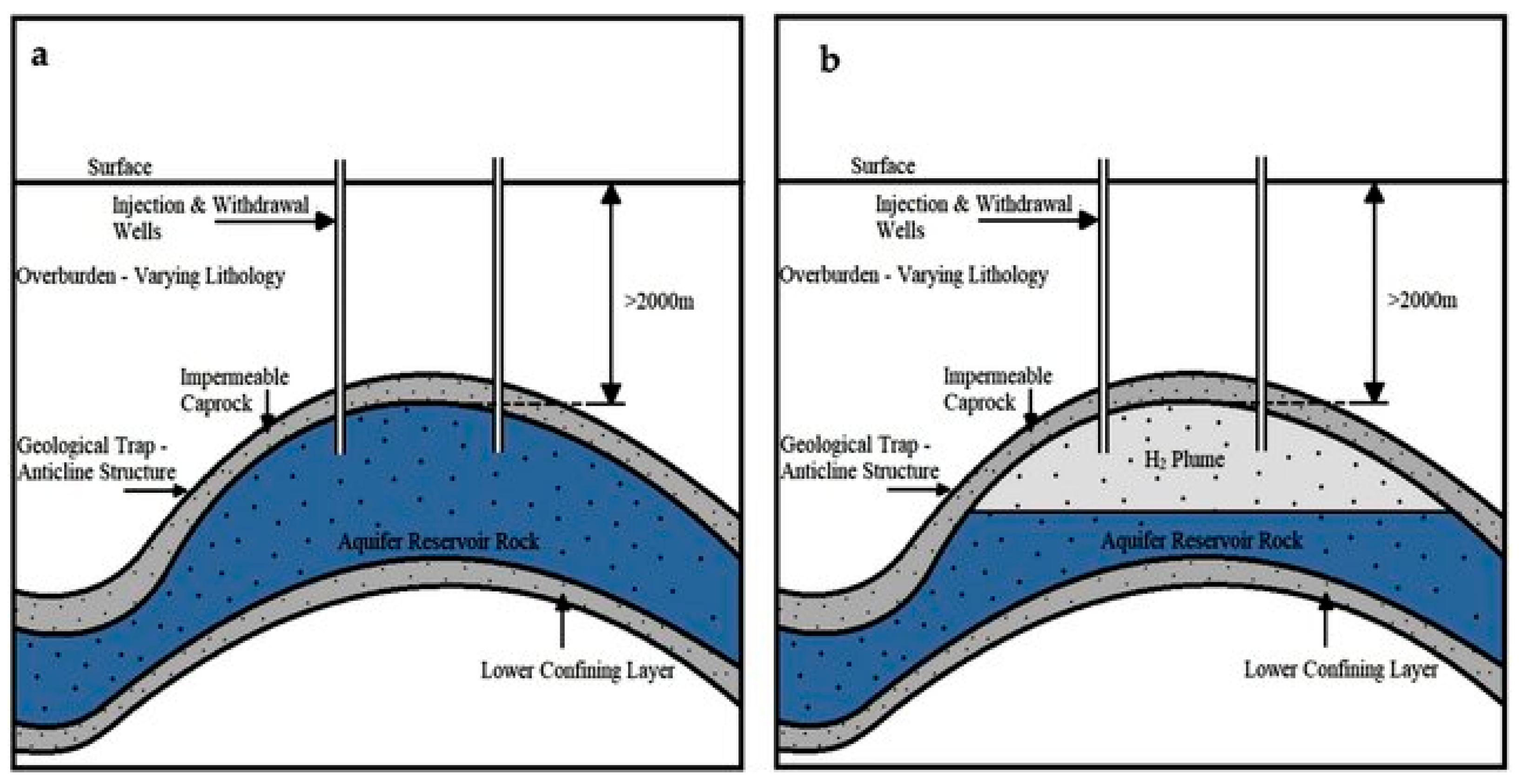

19]. A generalized depiction of aquifer structure before and after hydrogen storage is seen in

Figure 2.

To address containment and compositional changes, advanced monitoring tools are required. These include 4D seismic surveys, downhole pressure and gas composition logging, and distributed fibre-optic sensing (DTS/DAS). State-of-the-art monitoring methods developed for carbon dioxide (CO

2) storage are being adapted for hydrogen, but new calibration curves are needed due to its different acoustic properties. In addition, RTM, incorporating microbial kinetics, mineral dissolution, and gas diffusion, is now a key element of feasibility assessments. Models such as TOUGHREACT and COMSOL Multiphysics are widely used [

44].

While modelling studies present precise yet limited data pools, large-scale field trials and specified regulatory approaches are necessary to validate the potential of aquifer-based hydrogen storage. As pointed out in [

34], hydrogen storage in porous formations is technically feasible but a biologically and geochemically complex undertaking that demands cross-disciplinary solutions.

3. Materials and Methods

The methodological framework of this study was developed to assess the technical feasibility, geochemical performance, and economic implications of underground hydrogen storage in aquifers. To ensure comprehensive coverage of the relevant processes, the approach combined geological characterization, thermodynamic modelling, reactive transport simulations, and techno-economic evaluation in an integrated workflow. This design allowed for the inclusion of geological, geochemical, microbiological, and engineering factors in a coherent assessment.

The first step was the definition of geological boundary conditions. Representative aquifers were selected based on published analogues from underground gas storage and carbon capture projects. Key reservoir properties included porosities of 15–25%, permeabilities in the range of 50–500 mD, and depths between 800 and 1500 m. Formation brines were considered to have salinities from 30 to 150 gr/L NaCl equivalent, which is consistent with known aquifer systems. Aquifers were assumed to be confined, with average reservoir thickness of 50–100 m and lateral dimensions sufficient to provide storage volumes at the terawatt-hour scale. Caprocks were assumed to be dominated by shale, with capillary entry pressures and mechanical strengths adequate for hydrogen containment.

Thermodynamic simulations were carried out to determine the behavior of the hydrogen–brine system under reservoir conditions. Hydrogen solubility in brine was estimated across a range of pressures, salinities, and temperatures to evaluate potential losses due to dissolution. These calculations accounted for the influence of brine salinity on reducing hydrogen solubility and therefore minimizing losses. Results were used to establish operational windows for pressure and temperature that balance containment safety with injection efficiency.

Reactive transport modelling was employed to simulate the coupled processes of gas injection, migration, dissolution, and microbial transformation. The simulations accounted for two-phase flow of hydrogen and brine within a porous medium and captured the temporal evolution of a free hydrogen bubble in the reservoir. Key outputs included pressure distribution, gas saturation, hydrogen dissolution into brine, and migration pathways. This modelling provided insights into the long-term stability of injected hydrogen, as well as the distribution of recoverable and unrecoverable fractions during cyclic storage.

Microbiological processes were explicitly represented in the modelling framework. Particular attention was paid to hydrogen-consuming microorganisms such as sulfate-reducing bacteria, methanogens, and acetogens. Their activity was parameterized using experimentally derived rates from laboratory studies under reservoir-like conditions. This allowed the estimation of potential hydrogen losses due to biological conversion and the associated formation of by-products such as methane, hydrogen sulfide, and acetate. These processes were recognized as critical factors influencing both recovery efficiency and gas quality.

Geomechanical analysis was undertaken to assess the mechanical integrity of the storage system. Maximum allowable injection pressures were determined by the strength of the caprock and the fracture gradient of the formation. This ensured that hydrogen injection and withdrawal cycles remained within safe operational limits, preventing caprock failure or fracture propagation. Stress and strain simulations were used to evaluate reservoir deformation and pressure build-up under different operational scenarios.

For the economic component, a levelized cost of storage analysis was performed to compare aquifer-based hydrogen storage with alternative underground storage options. Capital costs considered in the model included drilling and completion of injection and monitoring wells, compression systems, and surface facilities. Operational costs included compression energy, cushion gas requirements, microbial mitigation treatments, and monitoring programs. The cost of unrecoverable hydrogen was also included as an operational penalty. The analysis was carried out over a 30-year project lifetime using a discounted cash flow method, enabling comparability with other energy storage technologies.

Cushion gas requirements were explicitly considered in the economic and technical analysis. Large volumes of cushion gas are needed to establish and maintain a stable hydrogen bubble within the aquifer. Scenarios tested included the use of hydrogen, methane, nitrogen, or carbon dioxide as cushion gases, with assessments of their impact on storage costs, retrievable gas quality, and long-term system stability. Trade-offs between chemical compatibility, purity of withdrawn hydrogen, and cost were central to this evaluation.

To address uncertainty, a probabilistic framework was applied. Monte Carlo simulations with 10,000 iterations were performed across a range of parameters including porosity, permeability, depth, microbial activity, and cushion gas fraction. This generated probability distributions for key outcomes such as recovery efficiency, dissolution losses, microbial consumption, and levelized storage costs. Sensitivity analyses identified the parameters exerting the greatest influence on technical and economic performance, providing insights into priority areas for future research and risk mitigation. All simulations were performed using a high-performance computing environment, enabling parallelized solution of the coupled flow and transport equations. Model validation was conducted against published benchmarks for underground natural gas storage and carbon dioxide storage to ensure consistency and credibility of the results. While hydrogen-specific experimental data remains limited, the validation exercise provided a solid basis for extending the framework to hydrogen storage.

The methodology was designed to reflect realistic operational conditions and constraints. Reservoir properties were parameterized using ranges consistent with known aquifers, while economic assumptions were aligned with recent underground storage projects and hydrogen infrastructure cost reports. Microbiological parameters were drawn from laboratory experiments on hydrogen-utilizing microbes in brine systems, and geomechanical properties were based on empirical correlations for sedimentary rocks. This integration of multiple evidence sources allowed for a robust and scientifically grounded assessment.

Framework for this study combines geological and reservoir characterization, thermodynamic modelling, reactive transport simulations, microbiological analysis, geomechanical evaluation, and economic modelling into a unified workflow. This multidisciplinary approach provides a holistic evaluation of the potential and limitations of aquifer hydrogen storage. The results generated through this methodology can guide both future scientific investigations and the development of pilot projects aimed at validating large-scale underground hydrogen storage.

4. Results

4.1. Risks Associated with Hydrogen Storage in Aquifers

Hydrogen storage in aquifers presents a series of unique scientific, technical, and operational challenges that differ significantly from conventional natural gas storage. While aquifers are widely used for natural gas in Europe, adapting them for hydrogen storage involves a complex convergence of hydrogen’s physicochemical properties, geological media, and long-term stability concerns.

4.1.1. Microbial Hydrogen Consumption and Rock-Fluid Interactions

One of the most significant risks of hydrogen storage in aquifers is the biological activity of native microorganisms of aquifer environments. Many aquifers harbour hydrogenotrophic microorganisms, such as SRB and methanogens, that can consume hydrogen as a substrate. This may lead to loss of stored hydrogen over time, generation of byproducts like H

2S and methane, which degrade gas quality and pose corrosion risks to the infrastructure, as well as unpredictable changes in gas composition requiring expensive purification upon withdrawal [

45].

Hydrogen is highly reactive under subsurface conditions and can participate in redox reactions with reservoir minerals. These interactions may result in dissolution or alteration of minerals, affecting porosity and permeability, the formation of secondary minerals that clog pore spaces, and adsorption losses due to hydrogen interaction with clay minerals or iron-rich formations. These geochemical processes can reduce storage capacity and damage reservoir productivity over time [

46].

Table 1 presents a summary of microbiological hazards in hydrogen-storing aquifers.

Reactive-transport simulations using Monod-type kinetics indicate that SRB H2 uptake rates in the modelled aquifer brines fall in the approximate range 0.01–0.5 mmol H2·L−1·day−1, while hydrogenotrophic methanogens exhibit rates of 0.005–0.3 mmol H2·L−1·day−1 under favourable conditions (moderate temperature, abundant electron acceptors). Converted to system-scale impacts, these rates correspond to ~0.1–8% SRB and ~0.05–6% methanogens of injected hydrogen lost per year for the parameter space considered. Worst-case combinations of low salinity, high sulfate/CO2 and warm temperature produced modelled microbial conversions up to ~20% over six months, whereas high-salinity/pH-controlled scenarios reduced microbial losses by ~80–90%. These estimates are sensitive to local biomass density, nutrient availability and residence time, and thus must be refined with site-specific laboratory incubations and in situ monitoring prior to full-scale implementation.

4.1.2. Hydrogen Diffusivity and Leakage Risk

Hydrogen’s low molecular weight and high diffusivity increase the risk of migration through caprock, faults, or poorly sealed wells. Compared to methane, hydrogen can more easily permeate through microfractures in the caprock, escape through cemented boreholes or abandoned wellbores and accumulate in unintended zones. Hydrogen diffusivity and leakage risk in aquifers represent critical technical and safety challenges in the development of large-scale underground hydrogen storage infrastructure. Hydrogen is the smallest diatomic molecule, with a molecular diameter of approximately 0.29 nm, which contributes to its exceptionally high diffusivity in both porous rock matrices and caprock systems.

Under reservoir conditions typical of aquifers with temperatures of 30–60 °C and pressures up to 80 bar, hydrogen exhibits significantly higher molecular mobility compared to methane. This increased mobility raises the risk of hydrogen migration from the intended storage zone, either through matrix diffusion or through discontinuities such as microfractures, abandoned wellbores, and imperfect caprock seals. Hydrogen’s diffusivity in water-saturated formations also contributes to potential mass loss through molecular dissolution in the brine. Although its solubility is relatively low at the standard level (~1.6 mg/L), under high pressure, a meaningful portion of stored hydrogen can dissolve into pore water and be transported via hydrodynamic flow, thus reducing the recoverable volume. This effect is especially relevant in formations with significant groundwater movement or low structural confinement. Moreover, the potential for caprock breach or leakage through abandoned wellbores becomes a serious concern in hydrogen storage due to its capacity to permeate through materials that may be impermeable to methane. Hydrogen embrittlement, a phenomenon where metals like carbon steel become brittle due to hydrogen infiltration, can compromise the integrity of casing and sealing components, particularly at the interfaces between different materials and pressure regimes [

52]. Scientific modelling using Fickian diffusion and RTM has shown that hydrogen’s diffusivity in porous geological media can range from 10

9 to 10

−6 m

2/s, depending on formation porosity, tortuosity, and temperature. These values are up to an order of magnitude higher than those for methane, reinforcing the need for robust geological containment [

53].

Caprock integrity, typically provided by low-permeability shales, clays, or evaporites, must be assessed for hydrogen transmissivity, as diffusion through nanometer-scale pores in these materials could allow gradual upward migration over extended storage periods. The presence of fault zones or micro-seepage pathways in the caprock may allow hydrogen to bypass containment barriers. Suppose migration leads to escape into overburden formations or the atmosphere. In that case, it not only represents a loss of stored energy but may also create safety hazards, given hydrogen’s flammability (4–75%) and explosive limits in air (4–59%) [

54]. Comparison of hydrogen and methane’s flammability and explosive limits in air is shown in

Table 2.

Hydrogen’s high diffusivity makes it significantly more challenging to contain in aquifers compared to methane or CO2. Addressing leakage risk requires a combination of high-resolution geological modelling, real-time monitoring systems, advanced sealing materials, and controlled injection/withdrawal strategies. While aquifers offer volumetric potential for seasonal hydrogen storage, their viability depends on overcoming these diffusivity and leakage-related constraints through rigorous site selection, geomechanical assessment, and engineered containment solutions.

4.1.3. Cushion Gas Requirements and Recovery Efficiency

Like methane, hydrogen storage in aquifers typically requires cushion gas, which is a non-recoverable gas that must remain in the reservoir to maintain pressure, displace water, and ensure efficient withdrawal of the working gas. Its role is to stabilise the pressure regime and create a gas bubble large enough to allow reversible storage and recovery cycles [

55]. Hydrogen, being less dense and more diffusive than methane, requires a carefully maintained pressure gradient to form and retain a distinct gas phase.

Without enough cushion gas, the hydrogen bubble may dissolve into formation water, mix uncontrollably, or migrate away from the target zone. For hydrogen storage in aquifers, the most suitable cushion gas is hydrogen itself, especially when high purity is required or when mixing with other gases is unacceptable. This is due to the following considerations: hydrogen cushion gas ensures chemical consistency in the reservoir. It avoids contamination of the working gas; other gases may be chemically or physically incompatible [

55,

56]. For instance, methane may mix with hydrogen and reduce purity, but inert nitrogen may alter gas density and reduce energy content upon withdrawal.

Table 3 depicts a comparison of cushion gas parameters for hydrogen storage in aquifers.

The volume of cushion gas required in aquifer hydrogen storage is higher than in methane storage because of hydrogen’s higher solubility in water and lower energy density [

20,

59]. Typically, 50–70% of the total storage volume in aquifer systems may be allocated to cushion gas, depending on reservoir characteristics and injection depth. Ref. [

60] also indicates that requirements for cushion gas can reach up to 80%. Aquifer storage requires a large volume of cushion gas to maintain pressure and displace working gas. For hydrogen cushion gas volume is higher than for methane due to lower molecular mass and energy density, recovery efficiency is lower, especially in the first cycles, due to hydrogen mixing with residual water and dissolution in brine, and there is a risk of hydrogen entrapment in isolated pore spaces, which may reduce storage’s economic feasibility. While hydrogen is ideal from a compatibility and purity standpoint, its cost and diffusivity impose operational challenges. Methane and CO

2 introduce purity and chemical risks, respectively, while nitrogen represents a technically neutral compromise and easier separation in recovery process [

61]. The optimal choice will depend on site-specific factors including formation characteristics, gas purity requirements, economic constraints, and the intended end-use of the recovered hydrogen [

33]. Robust modelling and site-specific pilot testing are necessary to validate the behaviour of the selected cushion gas under real subsurface conditions.

4.1.4. Monitoring and Gas Quality Control

Monitoring and gas quality control is crucial because aquifers are dynamic systems, continuous monitoring of pressure, temperature, gas composition, and microbial activity is crucial. Unlike salt caverns or depleted hydrocarbon fields, aquifers may have less geological data available, higher variability in formation water chemistry, more complex flow patterns requiring advanced reservoir simulation tools. Any contamination or loss of hydrogen must be identified early to maintain operational control and avoid safety risks.

4.2. SWOT Analysis

SWOT analysis is a highly useful methodological tool for assessing the feasibility and strategic viability of hydrogen storage in aquifers. This qualitative-analytical framework offers a structured yet flexible approach to synthesising multidisciplinary data and identifying key performance drivers and risk factors that influence the success or failure of subsurface hydrogen storage initiatives. Its relevance to aquifer-based hydrogen storage stems from the complexity and interdependence of technical, geological, environmental, and regulatory variables involved in such projects.

Hydrogen storage in aquifers is inherently interdisciplinary, combining subsurface engineering, fluid dynamics, geochemistry, microbiology, and environmental risk assessment [

57,

62]. A SWOT analysis enables researchers and project developers to categorise these factors holistically. For instance, geological strengths such as high porosity and the widespread availability of saline aquifers across Europe can be identified. At the same time, weaknesses, including microbial degradation of hydrogen and uncertain caprock integrity, can be systematically isolated for further risk mitigation planning. This mapping allows for early-stage decision support by integrating diverse inputs without requiring complete datasets, which is especially valuable in exploration or pre-feasibility project stages.

4.2.1. Strengths

Hydrogen storage in aquifers benefits from extensive volumetric scalability, owing to the widespread geological availability of porous and permeable sedimentary formations. These aquifers, often located at depths of 500 to 1500 m, can theoretically accommodate TWh-scale seasonal energy storage, essential for balancing intermittent renewable electricity production. Compared to salt caverns or depleted hydrocarbon fields, aquifers are geographically more distributed and potentially accessible in regions lacking fossil fuel infrastructure. General comparison of aquifers, salt caverns, and depleted gas fields as gas storage is summarized in

Table 4.

The technological foundation for aquifer storage has been established through decades of experience with natural gas storage, particularly in Europe. Facilities like Incukalns underground gas storage in Latvia provide an operational framework, including well construction, pressure control, and caprock integrity management, that can be adapted for hydrogen [

58,

63]. Thermodynamically, hydrogen exists as a supercritical or dense gas under the typical aquifer storage conditions (~30–60 °C and 60–100 bar), enabling relatively efficient packing and withdrawal, albeit with lower volumetric energy density than methane.

From an economic viewpoint, the initial infrastructure cost of using aquifers may be lower than creating salt caverns, particularly in regions where deep salt formations are not present [

59,

64]. The widespread nature of aquifers means that storage sites can be developed near hydrogen production hubs, reducing transport losses and allowing localised energy systems or microgrids to evolve around subsurface energy buffers.

4.2.2. Weaknesses

Despite obvious advantages, aquifer storage presents several scientifically rooted weaknesses. A primary limitation is hydrogen’s high diffusivity and solubility in water, which leads to losses as hydrogen dissolves into brine and diffuses into the rock matrix. While solubility is modest (~1.6 mg/L at STP), at high pressures and with large surface areas of contact, the cumulative effect over time can significantly reduce storage efficiency and recovery rates.

Moreover, aquifers are biologically active environments, often hosting anaerobic microbial communities capable of metabolising hydrogen. Hydrogenotrophic methanogens, SRB, and acetogens can convert hydrogen into methane, H2S, or organic acids, contaminating the stored gas and reducing the retrievable energy content. These microbial transformations may not only lower gas quality but also increase pipeline corrosion risks due to acidic or sulfuric byproducts.

Caprock integrity is another critical issue. Hydrogen’s small molecular size (~0.29 nm) allows it to migrate through nanoporous materials, microfractures, or legacy wellbore seals more readily than methane. Hydrogen embrittlement of steel components and cement degradation in well infrastructure further increase the risk of leakage over extended periods, especially in formations not originally designed for long-term hydrogen retention [

60,

65].

Aquifer storage requires a significant volume of cushion gas to maintain reservoir pressure and create a stable hydrogen bubble. To avoid contamination and maintain chemical uniformity of hydrogen, the cushion gas can be of the same composition. This increases the initial gas requirement and capital expenditure for facility startup. However, other types of cushion gases—methane and nitrogen- are also possible to be used.

4.2.3. Opportunities

Hydrogen storage in aquifers aligns directly with the EU’s Hydrogen Strategy and broader climate neutrality targets. It offers a means of seasonal or long-duration energy storage to match hydrogen production via electrolysis with a variable renewable energy supply. In regions with abundant offshore wind or solar, aquifer storage could serve as a buffering mechanism, allowing surplus hydrogen to be stored during periods of low demand and released when required by industry, heating networks, or power generation.

Emerging technologies in geophysical monitoring (electrical resistivity tomography, 4D seismic, fibre-optic sensors, etc.) and chemical sensing enable more precise surveillance of subsurface gas behaviour.

Aquifer storage could support the development of hydrogen hubs or clusters, where centralised hydrogen production, underground storage, and end-use sectors (mobility, industrial heating, ammonia synthesis) are co-located. These systems reduce the need for long-distance pipeline transport, thus lowering transmission losses and infrastructure costs.

Advances in microbial inhibition strategies, such as the injection of biocides or buffering agents, could suppress hydrogen-consuming bacteria and improve storage fidelity. Furthermore, the development of standardised regulatory frameworks, as is currently underway in Germany and the Netherlands, can unlock public and private investment in demonstration projects.

4.2.4. Threats

The scientific and commercial viability of hydrogen aquifer storage remains largely unproven at scale. Most current understanding is based on numerical modelling, laboratory simulations, and analogues from natural gas storage. The absence of real-world pilot facilities that have demonstrated multi-cycle, high-efficiency hydrogen withdrawal from aquifers limits stakeholder confidence.

From a policy standpoint, regulatory uncertainty is a major bottleneck. In many jurisdictions, laws governing underground gas storage were designed for hydrocarbons and do not account for hydrogen’s unique risks (flammability, embrittlement, microbial sensitivity). This gap delays permitting processes and raises legal liabilities.

Aquifer heterogeneity, both in terms of geological structure and fluid chemistry, makes site characterisation difficult and site-specific. Faults, variable porosity, and unexpected caprock discontinuities could result in subsurface hydrogen migration, presenting environmental and safety risks, especially if migration leads to aquifer contamination or surface leakage.

Competition from salt cavern storage, which offers superior containment, easier gas purity control, and proven cycling capability [

59], may divert investment from aquifer-based approaches. Without clear cost or access advantages, aquifer projects risk being marginalised in the evolving hydrogen infrastructure ecosystems.

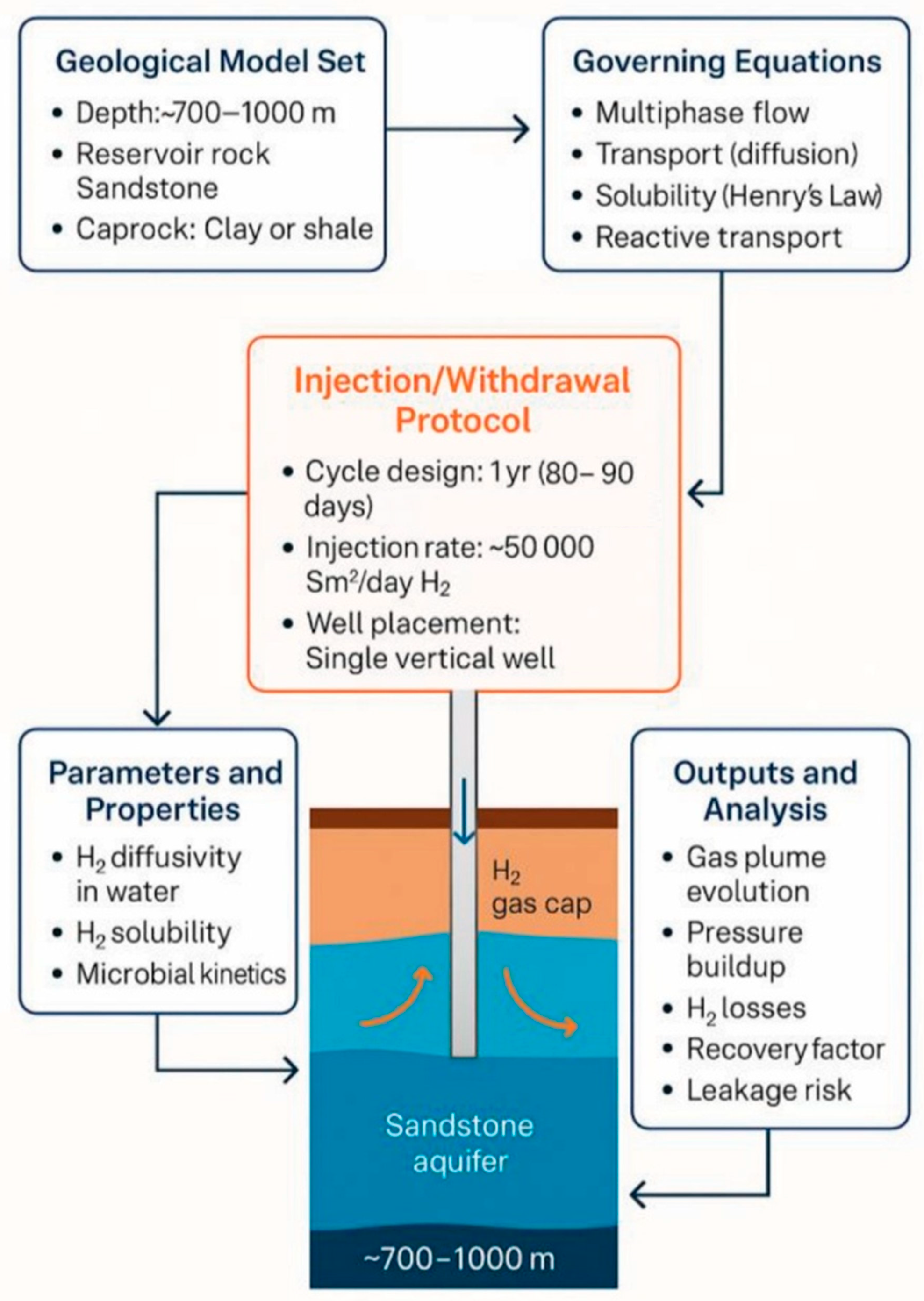

4.3. Proposed Technical Design for Hydrogen Storage in an Aquifer

Technical design layout for the creation of a large-scale hydrogen underground storage in an aquifer includes all surface and subsurface infrastructure, operational controls, and safety systems mandatory for objects of this type and operational purpose. The layout follows best practices in underground gas storage and adapts them to the specific physical and chemical requirements of hydrogen. The principal scheme of technical design layout for storage is depicted in

Figure 3.

4.3.1. Site Selection and Geological Criteria

Optimal aquifers are typically located at depths between 700 and 1200 m, where formation pressures range from 60 to 100 bar, allowing hydrogen to be stored in a dense gas phase suitable for long-term containment. The choice of rock type is critical; ideal reservoirs are composed of high-porosity, high-permeability sandstone with porosity values ranging from 20 to 25% and permeability between 100 and 300 mD. These properties facilitate efficient gas injection, migration, and withdrawal, while also supporting the formation of a stable hydrogen bubble within the pore network.

To ensure containment, a low permeability caprock must overlay the storage reservoir. This caprock is typically a shale or clay layer with a thickness exceeding 30 m and permeability lower than 106 mD, providing the necessary seal against vertical gas migration. The structural integrity of storage formation is equally important.

The target reservoir should possess an anticlinal trap geometry or be bound by fault seals or salt structures to ensure lateral and vertical confinement. These geological configurations prevent gas escape and enhance the predictability of gas plume behaviour during injection and withdrawal cycles. The main geological criteria for site selection for hydrogen storage in aquifers are summarised in

Table 5. The table serves as a comprehensive checklist for evaluating the geological suitability of candidate sites for hydrogen storage in aquifers.

Another essential consideration is the geochemistry of water formation. The aquifer should exhibit low concentrations of sulfate and iron ions to minimise the risk of hydrogen-consuming microbial activity and corrosion of well infrastructure. SRB and hydrogenotrophic bacteria are known to metabolise hydrogen, producing undesirable by-products such as H2S, which can degrade gas quality and damage storage integrity. Similarly, high iron content can catalyse unwanted abiotic reactions or clog pore spaces via mineral precipitation.

4.3.2. Subsurface Infrastructure

Injection/Withdrawal wells:

dual-function horizontal or deviated wells in the gas zone,

materials: high-grade steel with hydrogen-resistant internal coating,

cementing: expanded gas-tight cement; hydrogen diffusion barrier additives,

safety equipment: blowout preventers, wellhead monitoring valves, annular pressure monitoring.

Cushion gas:

injected hydrogen as cushion gas, 50–60% of total storage volume,

pressure stabilised to avoid caprock stress thresholds.

Monitoring wells:

placement: perimeter and above-caprock vertical wells,

sensors: pressure, temperature, gas composition, and micro-seepage detection,

fibre-optic sensing: Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) and Distributed Temperature Sensing (DTS).

4.3.3. Surface Infrastructure

Compression and injection system:

compressor station for hydrogen pressurization (max 100 bar),

flow control to allow variable-rate injection and withdrawal,

real-time leak detection and emergency shutoff.

Gas treatment unit:

pre-injection: hydrogen drying and purification (if from electrolysis),

post-withdrawal: dehydration, sulfur compound removal, gas blending unit (if needed for grid compatibility).

Monitoring and control:

SCADA system: supervisory control and data acquisition for all wells and pipelines,

geochemical lab module: in-situ brine analysis, microbial sampling,

meteorological Station: tracks weather, wind speed for safety and dispersion modeling.

Safety and Environmental Systems

Containment and seepage barriers:

multilayer impermeable wellhead enclosure,

surface bunds and secondary containment zones around pipelines.

Emergency systems:

flare stack or catalytic recombiner for hydrogen venting,

gas detection and automatic isolation valves in all enclosures.

Environmental baseline and monitoring:

groundwater sampling wells,

soil gas flux sensors for surface leakage,

CO2, H2S, and H2 continuous gas chromatograph monitoring stations.

Operational protocols:

injection phase: about 3 months/year during surplus renewable production,

shut-in period: about 3–6 months for microbial and geomechanical stabilisation,

withdrawal phase: about 3 months for demand periods or export.

The proposed technical design layout for hydrogen storage in an aquifer demonstrates a technically grounded and systemically integrated approach, aligning with current scientific understanding and industry’s best practices. However, a critical analysis reveals several areas that warrant further scrutiny, optimisation, or clarification, particularly about hydrogen-specific challenges that differ from those encountered in conventional natural gas storage.

A notable strength of the design is its emphasis on geological suitability, targeting porous sandstone formations with robust caprock layers. The specification of depth (700–1200 m) and pressure (60–100 bar) is appropriate for maintaining hydrogen in a dense gas phase, facilitating storage efficiency and pressure stability. However, while anticlinal structures offer natural trapping potential, the presence of microfractures or fault-related pathways in even well-characterised formations cannot be ruled out. Thus, seismic integrity mapping and long-term caprock creep modelling should be explicitly integrated into the site characterisation protocol.

The subsurface infrastructure includes appropriately hydrogen-resistant materials, such as coated steel casings and gas-tight cement. Nevertheless, long-term exposure tests under real reservoir conditions are required to validate the performance of these materials, particularly concerning hydrogen embrittlement and micro-leakage through annular spaces. The use of hydrogen as cushion gas ensures purity and chemical compatibility but imposes a high initial gas demand, making the project capital-intensive. Alternatives, such as inert gases like nitrogen in specific layers, may merit investigation to reduce startup costs if gas separation on withdrawal is feasible.

Regional differences in drilling and infrastructure costs have a significant influence on the overall economic feasibility of aquifer hydrogen storage. While the baseline model in this study applied averaged European cost data, cost benchmarks indicate that notable regional variations exist across the continent [

66]. Drilling and completion costs in Eastern Europe are generally 25–30% lower than in Western Europe or Germany, primarily due to reduced labor and service expenses [

67]. Surface infrastructure components like compressors, monitoring systems, and SCADA installations, exhibit smaller differences, typically in the range of 10–15%. These regional variations can result in total CAPEX deviations of approximately ±20–35% depending on the project location. Consequently, regional adjustment factors should be applied when transferring the model to specific national contexts, ensuring accurate reflection of local market conditions and infrastructure maturity [

66].

The design’s inclusion of fibre-optic monitoring (DAS/DTS), geochemical sampling, and real-time well control via SCADA systems reflects advanced instrumentation. However, operational complexity and maintenance overhead in such systems can be high, particularly in remote or unmanned field locations. Contingency plans must be developed for data redundancy, sensor drift, and cybersecurity threats to automated systems. Additionally, microbial risks, although acknowledged, are not sufficiently mitigated. The layout would benefit from incorporating biocide injection loops, microbial inhibition zoning, or biofilm-resistant coatings in wells, especially in formations with known microbial presence.

On the surface, the design addresses both hydrogen preconditioning (drying and purification) and post-withdrawal treatment. Yet, gas purity control during withdrawal is likely to be more challenging than described, due to possible mixing with dissolved hydrogen, microbial by-products, or entrained brine aerosols. Modular, mobile gas separation units could be added to enhance flexibility and on-demand purification capability. Also, if necessary, special case-specified, multi-stage gas purification units can be built, as in the case of landfill gas purification from sites with challenging gas purity maintenance conditions.

Emergency systems, such as flare stacks and automated isolation valves, are sound in principle but assume reliable containment. Given hydrogen’s low ignition energy and broad flammability range, a more detailed dispersion and ignition risk model should underpin the safety architecture. Passive containment (hydrogen-absorbing walls or underground vaults) and active recombination systems may provide additional security layers.

While the design outlines a structured annual operation, it assumes relatively stable demand and production cycles. In a real-world renewable-driven grid, hydrogen generation may be more erratic. The system should include buffering capacity, flexible injection rates, and integration with grid-scale energy management systems to adapt to fluctuating supply and demand patterns.

The technical design is commendably comprehensive and shows strong alignment with established subsurface gas storage principles. Nonetheless, its implementation must address the chemical, microbial, and dynamic behaviour of hydrogen with greater precision, while enhancing operational resilience and cost-effectiveness. These improvements are critical for transitioning from a theoretically sound model to a viable, field-deployable hydrogen storage solution.

5. Economic Feasibility Pre-Evaluation and Non-Monetized Benefits

5.1. Economic Feasibility Pre-Evaluation

An economic feasibility study was conducted for a large-scale underground hydrogen storage in an aquifer with a working volume of 1 BCM. Several strategic and technical considerations guided the choice of such storage capacity for the economic feasibility study. Firstly, this scale aligns with the energy storage requirements projected for the EU’s hydrogen infrastructure under decarbonisation targets.

According to models supporting the EU Hydrogen Strategy and the REPowerEU plan, seasonal and strategic-scale hydrogen storage needs may exceed 40–50 TWh by 2030. A 1 BCM aquifer, assuming a working volume of 0.5 BCM and a hydrogen energy density of approximately 3 kWh/m3, would provide roughly 1.5 TWh of usable energy, making it a representative benchmark unit.

Secondly, the selected capacity reflects a realistic yet ambitious scale for a single geologically viable site. Many aquifers across Europe, particularly in the Netherlands, Germany, and parts of Eastern Europe, can support such volumes, based on current subsurface reservoir data. Thus, it serves as a practical case study for pilot-to-commercial scale deployment scenarios.

Thirdly, this capacity enables meaningful participation in system-level energy balancing, including seasonal storage, industrial-scale hydrogen supply, and support for renewable integration. It is large enough to test hydrodynamic, economic, and infrastructure feasibility at scale, while remaining modular and scalable within larger hydrogen networks. Hence, 1 BCM offers a balance between engineering realism and policy relevance, making it a suitable choice for feasibility modelling and scenario planning.

An economic feasibility study’s results could theoretically be applied to the Dobele structure, part of Latvia’s Cambrian sandstone aquifer system, with a documented storage capacity of approximately 5–10 BCM (active gas ~5 BCM). With a porosity of about 23%, permeability of 500 mD, depth of about 950 m, and sealed by Ordovician shale, Dobele is geologically suited for hydrogen storage in future. Using a conservative subsurface volume of 1 BCM, this assessment evaluates foundational costs, acknowledging economies of scale for this large structure [

34,

61,

62,

68]. The main characteristics of the Dobele structure are listed in

Table 6.

The economic feasibility analysis of a hydrogen storage facility in an aquifer with a chosen working volume reveals a complex interplay between technical performance, operational costs, and market conditions. CAPEX is driven primarily by subsurface drilling, reservoir preparation, surface infrastructure, and cushion gas acquisition, particularly when pure hydrogen is used to maintain gas purity and compatibility. Below, the main expenditure category breakdown for the project is presented, with a cost category A covering subsurface costs, and category B—surface infrastructure.

- A.

Subsurface costs

Well drilling (2 items): EUR 10 million/each—EUR 20 million

Completion and casing: EUR 5 million/each—EUR 10 million

Cushion gas procurement (pure H2):

- o

gas cushion volume − 0.5 × 1 × 109 − 5 × 108 m3

- o

price (delivered) ~1 EUR/kg; hydrogen density ≈ 0.09 kg/m3 − ~5 × 107 kg − EUR 50 million

Reservoir characterisation/seismic studies: about EUR 20 million

- B.

Surface infrastructure

Compression and piping: ~EUR 80 million

Injection/dehydration/monitoring: ~EUR 40 million

Control systems (SCADA, sensors): ~EUR 20 million

Contingency (15% of subsurface + surface): ~EUR 34.5 million

Operating costs (OPEX), estimated at around EUR 24 million a year, are largely composed of fixed maintenance, compression energy, hydrogen losses due to dissolution, leakage, and microbial activity, as well as regulatory and insurance costs. The annual OPEX estimate consists of the following categories:

Fixed operations and maintenance: EUR 10 million

Compression energy: 5 × 108 m3 × 0.2 kWh/m3 × EUR 0.06/kWh = EUR 6 million

Cushion gas losses (10%): EUR 6 million

Compliance and insurance: EUR 2 million

Projected revenue from hydrogen sales, grid balancing services, and supplementary contracts, estimated at roughly EUR 16 million/year, is insufficient to cover the total annual expenses, resulting in a negative net cash flow under the base case scenario. This indicates that without significant intervention or value optimisation, the investment payback period would exceed 30 years, and NPV would remain negative.

However, the analysis also highlights several leverage points that could enhance the financial viability of such projects. First, increasing the sale price or net margin per kilogram of hydrogen, whether through premium industrial contracts, mobility markets, or green hydrogen certification, could significantly improve revenue. For example, raising the hydrogen sales price to EUR 2.50 per kilogram would increase annual income and reduce the operating deficit substantially.

Also, reducing operational inefficiencies, especially by minimising cushion gas losses through improved well integrity and microbial control, can lower annual costs. Even a modest reduction in hydrogen leakage from 10% to 5% could yield cost savings of EUR 3 million annually.

Furthermore, the inclusion of system-level externalities such as carbon pricing and capacity payments for long-duration storage services would improve the economic profile. Additional value from carbon credits is an avoidance of 60,000 t of CO2. At a carbon credit standing of EUR 50/t, it would convert into an additional yearly benefit of EUR 3 million.

Results of cost optimisation analysis for CAPEX and OPEX are presented in

Table 7.

At the same time,

Figure 4 presents quantitative relationship between cushion gas price and CAPEX for a large-scale underground hydrogen storage project.

The analysis assumes that 50 million kg of hydrogen are required to serve as cushion gas for pressure stabilization within an aquifer. The figure functions as a sensitivity matrix, allowing stakeholders to evaluate how varying market prices for hydrogen influence the overall upfront investment required for storage infrastructure. Figure demonstrates the linear dependency between the unit price of hydrogen and the total cost of acquiring the necessary quantity for cushion gas purposes. For example, if the hydrogen market price is set at EUR 1/kg, the total cushion gas cost would be EUR 50 million. If the price rises to EUR 1.50/kg, the cost increases proportionally to EUR 75 million. Conversely, in a scenario where green hydrogen production costs decrease to EUR 0.80/kg due to technological improvements or subsidies, the cushion gas cost would drop to EUR 40 million. These calculations are crucial because cushion gas often represents a significant share, up to 20–25%, of the total CAPEX for hydrogen storage in aquifers. The figure allows stakeholders to visualize not only direct cost implications but also potential strategic responses. If hydrogen prices remain elevated, project developers might explore alternative hybrid cushion gas strategies using inert gases like nitrogen or CO2.

Again, to compare the cost per kWh stored and recovered for three key types of underground hydrogen storage systems: aquifers, salt caverns, and depleted hydrocarbon fields, cost data from recent feasibility studies, industry reports, and academic sources are used. The metric calculated is EUR/kWh, including both CAPEX and OPEX normalized by energy stored and recovered.

Assumptions used in calculation are as follows: energy density of H

2 at standard storage pressure—3.0 kWh/m

3, lifecycle of the storage—30 years, discount rate—8% and utilization rate in cycles/year for aquifer—1, salt cavern—10, and depleted hydrocarbon fields—3. Recovery efficiency for aquifer is 70%, for salt cavern—95% and for depleted field—85%. Cost inputs for 1 TWh usable storage capacity are summarized in

Table 8.

Cost per kWh Stored and Recovered

Using the Levelized Cost of Hydrogen Storage (LCOHS) formula:

where CFR = Capital Recovery factor is calculated as follows:

r—0.08,

n—30,

CFR = ~0.0888

As seen in

Table 9, salt caverns offer the lowest LCOHS in EUR/kWh due to high recovery efficiency and high cycling capability, making them ideal for frequent dispatch. Depleted fields again are moderately cost-effective, especially for seasonal storage, but have more complex sealing and monitoring needs. Aquifers currently show the highest cost per usable kWh, driven by lower recovery efficiency and higher uncertainty. However, their geographic availability and potential for scalability still make them a key candidate for long-term, strategic storage—especially when non-monetized system benefits are considered.

Along with comparison of the LCOHS in EUR/kWh stored and recovered for three key types of underground hydrogen storage systems, a quantitative comparison of lifecycle emissions or efficiency also needs to perform and presented. The data presented in

Table 10 provide such a comparative assessment. The analysis focuses on four key emission categories: construction, compression and injection, withdrawal and purification, and leakage-related losses, culminating in estimates of total lifecycle emissions per kilogram of stored hydrogen. In addition, relative storage efficiency is compared across the three storage types.

Results reflected in

Table 10 indicate that salt caverns are the most favorable option in terms of both emissions and efficiency. Construction emissions range from 0.05 to 0.10 kg CO

2-eq/kg H

2, which is lower than both depleted fields (0.07–0.15) and aquifers (0.10–0.18). The same trend is observed for compression and injection requirements, where salt caverns require only 0.03–0.05 kg CO

2-eq/kg H

2, compared to 0.04–0.06 for depleted fields and 0.05–0.07 for aquifers. Withdrawal and purification steps also contribute less in caverns (0.01–0.03) relative to aquifers, which record the highest values (0.03–0.05). Leakage-related losses are minimal in salt caverns (<0.005), while aquifers show significantly higher ranges (0.02–0.06), reflecting geological heterogeneity and sealing uncertainties.

Depleted hydrocarbon fields represent an intermediate solution, with moderate construction and operational emissions. They offer the advantage of existing infrastructure and geological knowledge, but their leakage risk (0.01–0.03) is notably higher than in caverns. Aquifers, while more widely distributed geographically, show the highest emissions across most categories, particularly due to greater leakage potential and higher requirements for purification.

The aggregated data on total lifecycle emissions underscore these differences: salt caverns exhibit the lowest range (~0.09–0.18 kg CO2-eq/kg H2), followed by depleted hydrocarbon fields (~0.14–0.28), and aquifers (~0.20–0.36). This positions salt caverns as the most sustainable storage option when available, though their geographical distribution is limited. In contrast, aquifers may expand storage potential geographically but at the expense of higher emissions and reduced efficiency.

In terms of storage efficiency, salt caverns again outperform, achieving levels above 95%. Depleted fields demonstrate medium efficiency (80–90%), while aquifers reach only medium-low levels (70–85%). This has direct implications for both the environmental footprint and the economic viability of large-scale hydrogen storage systems.

5.2. Non-Monetised Benefits

Hydrogen storage in aquifers also offers a range of non-monetised benefits that, while not immediately reflected in project cash flows or balance sheets, carry significant strategic, environmental, and systemic value. These intangible or external benefits are essential to understanding the broader role of aquifer-based hydrogen storage within the European energy transition framework.

One of the most prominent non-monetised benefits is seasonal energy balancing. Unlike batteries or short-term storage technologies, aquifer hydrogen storage enables the accumulation of excess renewable electricity, coming from solar generation surpluses in summer or wind peaks in autumn, and its conversion to hydrogen for use in winter months. This capacity to buffer multi-month variability ensures that renewable energy is not curtailed due to overgeneration, thereby maximising utilisation rates and increasing the effective penetration of clean electricity in the grid.

A second critical benefit is grid flexibility and system resilience. As more variable renewable energy sources are integrated into power systems, the grid becomes increasingly sensitive to fluctuations in generation. Hydrogen storage allows for demand-shifting and grid support services that help maintain frequency, voltage, and reserve margins without fossil backup. In doing so, it reduces reliance on peaking plants, shortens response times to imbalances, and enhances the reliability of the electricity supply.

The decarbonisation of hard-to-abate sectors is another strategic value. Hydrogen stored in aquifers can be recovered and supplied on demand to sectors such as steelmaking, shipping, and heavy road transport. These sectors cannot be easily electrified and require large, flexible volumes of energy-dense fuels, making large-scale geological storage a necessary infrastructure backbone for a hydrogen-based industrial economy.

Hydrogen storage in aquifers enhances energy security and sovereignty as well. By enabling domestic and regional storage capacity, countries can reduce dependency on imported fossil fuels or hydrogen derivatives. During supply shocks, geopolitical tensions, or emergencies, stored hydrogen can act as a strategic reserve, like oil stockpiles, strengthening national resilience.

From an environmental standpoint, storing renewable hydrogen underground helps to displace carbon-intensive fuels without requiring land transformation. Unlike hydrogen storage tanks or industrial terminals, aquifer storage has a minimal land-use footprint and avoids visual or social disruption, which contributes to better public acceptance and regulatory compliance.

Knowledge and innovation spillovers associated with aquifer storage projects drive advancements in geoscience, hydrogen-compatible materials, and subsurface monitoring technologies. These developments have applications beyond hydrogen, including carbon capture and storage, geothermal energy, and digital twin development for subsurface systems.

Hydrogen storage in an aquifer may face financial hurdles in early-stage deployment, but its non-monetised benefits significantly strengthen its societal and systemic justification. Recognising and incorporating these benefits into energy policy, planning, and valuation models is critical to fostering a resilient, decarbonised energy system. Another critical factor is the role of public support. Capital cost-sharing through the EU green infrastructure funds, innovation grants, or hydrogen valley programs can reduce the upfront burden and improve project bankability. Likewise, integrating such storage systems into hydrogen hubs or energy clusters may unlock economies of scale and logistical efficiencies.

While the base financial model for aquifer-based hydrogen storage on a commercial scale appears challenging, the underlying strategic, environmental, and system-integration value of such facilities remains strong. With targeted cost optimisations, improved operational efficiency, supportive regulation, and recognition of system-level benefits, hydrogen aquifer storage can become an economically viable and vital component of the EU’s energy transition and climate strategy.

6. Discussion

The results of this study provide new insight into the technical feasibility, system design considerations, and economic viability of underground hydrogen storage in aquifers, a storage pathway that remains underexplored compared with salt caverns and depleted hydrocarbon reservoirs [

6,

27,

42,

63,

64,

69]. The findings confirm that aquifers can, under appropriate geological and operational conditions, provide substantial volumetric capacity for hydrogen storage, yet they also highlight critical physicochemical and microbiological processes that must be carefully addressed before large-scale deployment. The analysis shows that the most significant challenges are related to hydrogen’s unique physical properties, including high diffusivity, low molecular weight, and solubility in brine, which collectively raise the risk of migration, dissolution, and energy losses compared with methane or CO

2 storage. In parallel, hydrogen’s role as a potential electron donor for microbial communities introduces biological consumption pathways that can alter gas quality, reduce recovery efficiency, and accelerate infrastructure corrosion. These risks differentiate aquifer hydrogen storage from natural gas storage analogues, making it clear that site-specific assessments and hydrogen-tailored designs are essential for ensuring technical success [

45,

46,

52,

65].

The study’s findings on microbial activity underscore the importance of brine chemistry and indigenous microbiota as determinants of storage performance. Sulfate-reducing bacteria, methanogens, and acetogens are capable of metabolising significant fractions of injected hydrogen, producing methane, hydrogen sulfide, and organic acids that compromise both energy recovery and operational safety. While laboratory experiments have confirmed hydrogen consumption of up to 20% over multi-month timeframes in brine-rich formations, modelling results indicate that careful site selection, biocide treatments, and brine conditioning can mitigate these losses. Thus, microbial management strategies must become integral to aquifer storage design, alongside traditional geomechanical and hydrodynamic considerations. At the same time, the geochemical reactivity of hydrogen with reservoir minerals further complicates the picture. Dissolution, adsorption, and mineral transformations can gradually alter porosity and permeability, potentially clogging pore networks and limiting injectivity. Reactive-transport modelling incorporated redox-sensitive mineral phases to evaluate long-term geochemical effects of hydrogen storage. Under the simulated brine chemistries (30–150 g/L salinity; 30–60 °C), hydrogen-driven iron reduction and secondary carbonate precipitation were found to induce minor porosity decreases (<2%) and permeability reductions below 5% over a decadal timescale. These changes were spatially restricted to the gas–brine interface and were mitigated by the limited availability of reactive Fe(III) and the buffering capacity of the formation water. Therefore, long-term mineralogical transformations are not expected to substantially impair injectivity under the modeled operational conditions. Nevertheless, it is recommended that field projects include periodic injectivity testing and geochemical monitoring to detect potential progressive alterations. These results suggest that aquifer-based hydrogen storage cannot be directly equated with natural gas storage and must be understood as a coupled geochemical, microbiological, and geomechanical system.

Hydrogen diffusivity and leakage potential emerge as central concerns in evaluating aquifer suitability. Compared with methane, hydrogen diffuses up to an order of magnitude faster through porous rock and caprocks, and its small molecular size increases the risk of seepage along fractures, abandoned wells, or imperfect cement barriers. Capillary entry pressure studies confirm that even dense shales may not completely inhibit hydrogen migration over decades. This implies that abandoned wellbores and structural discontinuities represent priority risk factors for containment [

33]. From a safety perspective, leakage of hydrogen into overlying formations or to the atmosphere introduces fire and explosion hazards, given hydrogen’s exceptionally low ignition energy and broad flammability limits. These findings strongly reinforce the necessity of rigorous integrity testing, long-term monitoring using seismic, fibre-optic, and geochemical methods, and the implementation of advanced wellbore sealing materials resistant to hydrogen embrittlement. Without such precautions, large-scale aquifer storage projects would remain vulnerable to both technical and safety failures.

The results also highlight the role and implications of cushion gas in aquifer storage systems. Unlike salt caverns, where cushion gas requirements are relatively modest, aquifers demand significant volumes, often 50–70% of the storage space, to create a stable hydrogen bubble and maintain pressure. Using hydrogen itself as cushion gas provides maximum chemical compatibility and avoids purity losses, but it represents a substantial upfront cost and immobilises large volumes of hydrogen in the formation. Alternatives such as methane, nitrogen, or CO

2 could lower startup costs but risk contamination, altered thermodynamics, or chemical incompatibilities. This trade-off underlines the economic sensitivity of aquifer storage projects to cushion gas strategies, with hydrogen purity requirements, end-use applications, and market conditions dictating the optimal solution [

56,

57]. From a system perspective, cushion gas procurement and retention emerge as one of the largest cost drivers in aquifer storage, and its optimisation represents a key research and policy priority.