Digital Twins for Cryogenic Hydrogen Safety: Integrating Computational Fluid Dynamics and Machine Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Databases searched: Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Keywords used: “hydrogen”, “hydrogen sensor,” “cryogenic hydrogen safety,” “digital twin,” “computational fluid dynamics,” “machine learning,” and combinations thereof.

- Time frame: Publications mainly from 2000 to 2025 were considered to capture both foundational and recent developments. However, articles from the last decade (2015–2025) were analysed in greater detail, as they represent the most up-to-date technological advances and safety considerations.

- Inclusion criteria: Peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, and authoritative reports that directly addressed hydrogen sensing technologies, cryogenic safety, or digital-twin/CFD–ML integration.

2. Physics of Liquid Hydrogen Jet Release and Combustion

2.1. Overview of Liquid Hydrogen Physics

2.2. Comparison Between Liquid and Gaseous Hydrogen Releases

2.3. Hydrogen Storage Technologies and Safety Considerations

3. Sensors

- Thermal sensors: The pellistor is a thermal detector that measures a change in resistance due to the heat generated by catalytic combustion on a bead. The resulting imbalance in a Wheatstone bridge produces an output voltage proportional to the concentration of flammable gas in the air. Similarly, Thermal Conductivity Detectors (TCDs) measure differences in thermal conductivity caused by the presence of hydrogen, again using a Wheatstone bridge to detect small electrical changes linked to altered heat transfer. These sensors are robust and fast-responding but typically require high power and show limited selectivity toward hydrogen compared to other gases.

- Electrochemical sensors: These rely on the oxidation of hydrogen at the anode, which produces a current in an external circuit. Two main types are employed: potentiometric, which measure changes in potential and follow the Nernst equation, and amperometric, which measure current changes between the working and counter electrodes. They are low-power and highly selective, making them suitable for portable and industrial applications. However, their performance deteriorates at low temperatures, likely due to constraints in electrode activity or redox reaction kinetics.

- Optical sensors: Optical detectors have demonstrated high precision in hydrogen detection but are often expensive or complex and, in many cases, remain at the research or laboratory development stage. Nevertheless, they are among the most promising options for cryogenic systems owing to the stability and robustness of their sensing materials under low-temperature conditions. Raman spectroscopy, a subclass of optical detection, measures frequency shifts in scattered light to identify the unique spectral fingerprint of hydrogen molecules. Other detectors based on absorption and emission principles exploit the interaction of hydrogen gas with infrared (IR) or ultraviolet (UV) radiation. A particularly well-established approach is the optical fiber sensor, which detects variations in light transmission or reflection induced by the presence of hydrogen. Numerous subcategories of optical fiber sensors exist, including the Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG), which employs periodic microstructures along the fiber to filter specific wavelengths. Another important class is surface plasmon resonance (SPR) sensors, which utilize metallic films—often palladium layers—that interact with hydrogen to modify the propagation of light. Several optical sensing concepts have been adapted for cryogenic environments. For example, Bévenot et al. [18] developed an optical fiber sensor capable of detecting hydrogen leaks in cryogenic rocket engines. The sensor, designed to operate between −196 °C and 23 °C, features a palladium-coated fiber tip that exploits the metal’s strong hydrogen absorption properties. The experimental setup combined the coated optical fiber with a laser source to monitor changes in reflectivity as an indicator of hydrogen presence. Although the tests were primarily performed at room temperature, the results demonstrated effective operation at low temperatures, aided by optical heating from the laser. Overall, optical sensors—particularly those employing palladium-based coatings—show strong potential for cryogenic hydrogen applications due to their high sensitivity, electromagnetic immunity, and suitability for harsh operating environments without requiring electrical power at the sensing point.

- Semiconductor sensors: A common example is the Metal Oxide Semiconductor (MOS) detector, which relies on changes in conductivity of a sensing material when exposed to hydrogen. The gas reacts with absorbed oxygen at the material surface, releasing electrons and thereby increasing conductivity. The resulting change in resistance is correlated with the hydrogen concentration. These sensors are compact and inexpensive, but they can suffer from cross-sensitivity to other gases and typically require regular calibration to ensure reliable long-term performance.

- Acoustic sensors: These devices rely on piezoelectric materials that generate an electrical charge when deformed by an acoustic wave. The adsorption of hydrogen molecules on the sensing surface alters the resonance frequency of the device. This frequency shift can result from mechanisms such as mass loading, catalytic oxidation (temperature change induced by reaction), or variations in gas concentration that modify the propagation velocity of the acoustic wave. Acoustic sensors can achieve high sensitivity, however, their performance is often affected by environmental conditions such as humidity and temperature. Among the most common designs are Surface Acoustic Wave (SAW) sensors [19], which employ substrates such as Pd, metal oxides, or polymers to absorb hydrogen molecules and therefore influence the acoustic wave traversing the surface. Another technology is the Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM), which measures frequency changes arising from hydrogen absorption in the sensing layer.

Sensors for Cryogenic Hydrogen

4. Safety Consideration Open and Enclosed Environments

5. Experimental Investigations of Hydrogen Dispersion

6. CFD Tools and Their Predictive Capabilities

6.1. Dispersion

6.2. Jet Fires

| Reference | Case of Study | Brief Description | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jet Fire: Geometry, Dynamics and Heat Transfer | |||

| [45] | Cryogenic hydrogen fires from storage with pressure up to 5 bar abs and temperature between 48 and 82 K | RANS (), combustion: EDC; radiation: DO (Discrete Ordinates) model in ANSYS FLUENT. | Flame length and radiative heat flux for cryogenic jet fires. |

| [46] | Sudden release from a 25 L tank at initial pressure of 930 bar through 2 mm orifice | RANS (), combustion: EDC; radiation: DO model in ANSYS FLUENT. | Dynamics of radiative heat transfer and flame length for under-expanded hydrogen jet fire (900 bar). |

| [44] | Six cases of under-expanded hydrogen and hydrogen/methane jet fires (horizontal/vertical); nozzle diameters 5.08–20.9 mm; tank pressures 33–105 bar; varying ground reflectance | LES turbulence; combustion: modified EDM; radiative transfer: fvDOM in FireFOAM. | Flame length and radiation characteristics of hydrogen and hydrogen/methane jet fires. |

| [47] | PRD activation of cylindrical Al-carbon fiber/epoxy composite vessel (900 mm length, 400 mm diameter); discharge pressures 10–40 MPa; barrier inclinations | SST turbulence; finite-rate/EDM combustion in SIMPLE. | Characteristics of hydrogen jet fires from Pressure Relief Devices (PRD). |

| Liquid Hydrogen (LH2) Dispersion | |||

| [40] | Spill diameter 26.6 mm; two horizontal and one vertical releases; spill rate 60 L/min; fluctuating wind direction | Simulations with ANDREA-HF code. | LH2 spill experiments on flat concrete pad in open environment (HSL data). |

| [48] | Horizontal open area m2; mass flow 9.52 kg/s; effects of wind velocity, temperature | Unsteady RANS with realizable model, enhanced wall treatment, ANSYS FLUENT. | LH2 spill dynamics on the ground, including vaporization and dispersion. |

| [41] | Two-phase jet, horizontal cross-section m; mass flow 9.52 kg/s; varying vapor cloud compositions | Mixture multiphase model with realizable turbulence and gas transport in ANSYS FLUENT. | Evolution and flow fields of flammable vapor cloud formed by LH2 spills. |

| High-Pressure Hydrogen Gas Dispersion | |||

| [43] | Parking compartment m; hydrogen release kg/s; multiple ventilation scenarios | turbulence model in FDS. | Dispersion of hydrogen gas in confined/semi-confined spaces from Fuel Cell Vehicle (FCV). |

| [42] | Underground parking garage with 12 slots; hydrogen leak from FCV corner; leakage area 5 cm square; leakage rates 131–1310 L/min; fan air volumes 20–60 m3/min | turbulence in STAR-CCM+. | Dispersion process of hydrogen leak in underground parking garage. |

7. Machine Learning for Hydrogen Safety

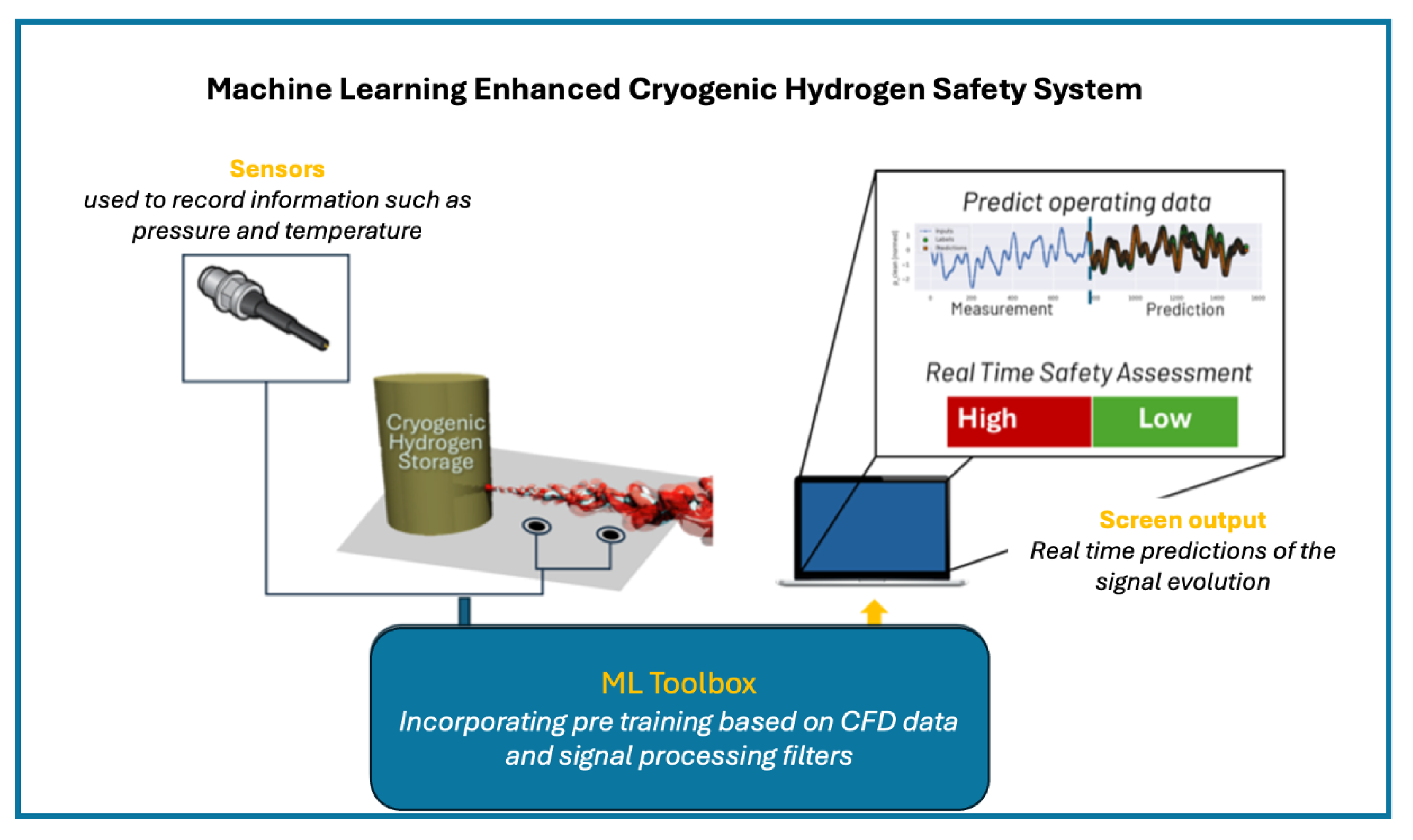

ML-Transformer Architecture

8. Conceptual Framework for Digital Twins in Cryogenic Hydrogen Systems

9. Conclusions and Discussion

- Dedicated test beds that combine sensing, modelling, and control, enabling future systems to move toward reliable real-time hydrogen safety management.

- In the computational front, one important area of research should be the development of surrogate models and reduced-order approaches specifically tailored for cryogenic conditions that can help speed up the prediction and monitoring process.

- Development of standardised data exchange protocols, metadata frameworks, and intermediate data layers that can translate between different sources. Recent advances in semantic data models and ontologies for engineering systems, along with cloud-based platforms for real-time data fusion, offer promising pathways to overcome these interoperability barriers.

- Moreover, real-time digital twins must incorporate robust methods for uncertainty quantification to ensure trustworthiness in safety-critical decisions.

- Cyber-physical integration further demands secure and fault-tolerant digital infrastructures. Addressing these challenges will require more enhanced interdisciplinary research.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Glover, A.; LaFleur, A.C.; Ehrhart, B. Report on General Hydrogen Safety; Technical Report; Sandia National Laboratories (SNL-NM): Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Cirrone, D.; Makarov, D.; Molkov, V. Hydrogen safety for systems at ambient and cryogenic temperature: A comparative study of hazards and consequence modelling. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2025, 95, 105606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mission Innovation Clean Hydrogen Mission. Hydrogen Detection Technologies for Hydrogen Safety: Applications and Technologies. 2023. Available online: https://mission-innovation.net/missions/hydrogen/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Mekonnin, A.S.; Wacławiak, K.; Humayun, M.; Ullah, H.; Zhang, S. Hydrogen Storage Technology, and Its Challenges: A Review. Catalysts 2025, 15, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Q.; Li, J.C.; Park, K.; Jang, S.J.; Kwon, J.T. An Analysis on the Compressed Hydrogen Storage System for the Fast-Filling Process of Hydrogen Gas at the Pressure of 82 MPa. Energies 2021, 14, 2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elberry, A.M.; Thakur, J.; Santasalo-Aarnio, A.; Larmi, M. Large-scale compressed hydrogen storage as part of renewable electricity storage systems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 15671–15690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peksen, M.M.; Wen, D. Dynamic Behaviour of Cryogenic Liquid Hydrogen Storage Tanks. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 149, 150028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Tian, Z.; Cullis, I.; Proud, W.G.; Hillmansen, S. Towards Sustainable Mobility: A Systematic Review of Hydrogen Refueling Station Security Assessment and Risk Prevention. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 105, 1266–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Lee, S.Y.; Park, S.J. Advancements in Hydrogen Storage Technologies: A Comprehensive Review of Materials, Methods, and Economic Policy. Nano Today 2024, 56, 102302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kytömaa, H.; Hur, I.Y.; Wechsung, A.; Faraji, S.; Dimitrakopoulos, G.; Cook, N.; Jaimes, D. Industry R&D Needs in Hydrogen Safety. Appl. Energy Combust. Sci. 2024, 180, 100271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberle, U.; Felderhoff, M.; Schüth, F. Chemical and Physical Solutions for Hydrogen Storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 6608–6630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehr, A.S.; Phillips, A.D.; Brandon, M.P.; Pryce, M.T.; Carton, J.G. Recent Challenges and Development of Technical and Technoeconomic Aspects for Hydrogen Storage: Insights at Different Scales; A State-of-the-Art Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 70, 786–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marnate, K.; Grönkvist, S. Looking Beyond Compressed Hydrogen Storage for Sweden: Opportunities and Barriers for Chemical Hydrides. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 77, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudio, N.D.N.; Bian, X.Q.; Chinamo, D.S. Liquid Hydrogen Carriers for Clean Energy Systems: A Critical Review of Chemical Hydrogen Storage Strategies. Fuel 2025, 404, 136329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnain, M.; Sezer, H.; Mason, J.H. Mathematical Modeling of Heat and Mass Transfer in Metal Hydride Hydrogen Storage Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 226, 116294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Yin, Z. Direct use of simulated seawater achieving superior H2 gas uptake in H2-DIOX hydrates for offshore hydrate-based H2 storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 169, 151041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bhattacharjee, G.; Kumar, R.; Linga, P. Solidified Hydrogen Storage (Solid-HyStore) via Clathrate Hydrates. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 133702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevenot, X.; Trouillet, A.; Veillas, C.; Gagnaire, H.; Clement, M. Hydrogen Leak Detection Using an Optical Fibre Sensor for Aerospace Applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2000, 67, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Ren, Z.; Wang, W.; Cheng, L.; Gao, X.; Huang, L.; Hu, A.; Hu, F.; Jin, J. Review of Surface Acoustic Wave-Based Hydrogen Sensor. Sens. Actuators Rep. 2024, 7, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrella, O.; Martucci, A.; Caruso, P.; Travascio, L.; Vozella, A. Hydrogen Safety: A Comparative Analysis of Leak Detection Sensors. In Proceedings of the 34th Congress of the International Council of the Aeronautical Sciences, Florence, Italy, 9–13 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Qanbar, M.W.; Hong, Z. A Review of Hydrogen Leak Detection Regulations and Technologies. Energies 2024, 17, 4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, S.K.; Kumar, A.; Mondal, S. Advancements in Hydrogen Gas Leakage Detection Sensor Technologies and Safety Measures. Clean Energy 2025, 9, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latka, I.; Ecke, W.; Höfer, B.; Chojetzki, C.; Reutlinger, A. Fiber Optic Sensors for the Monitoring of Cryogenic Spacecraft Tank Structures. In Proceedings of the Photonics North 2004: Photonic Applications in Telecommunications, Sensors, Software, and Lasers, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 26–29 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pijolat, C.; Tournier, G.; Breuil, P.; Matarin, D.; Nivet, P. Hydrogen Detection on a Cryogenic Motor with a SnO2 Sensors Network. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2002, 82, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witcofski, R.; Chirivella, J. Experimental and analytical analyses of the mechanisms governing the dispersion of flammable clouds formed by liquid hydrogen spills. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1984, 9, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verfondern, K. Experimental and theoretical investigation of liquid hydrogen pool spreading and vaporization. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1997, 22, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royle, M.; Willoughby, D. Releases of Unignited Liquid Hydrogen. 2014. Available online: https://www.h2knowledgecentre.com/content/policypaper1196 (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Hall, J.E.; Hooker, P.; Willoughby, D. Ignited releases of liquid hydrogen: Safety considerations of thermal and overpressure effects. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 20547–20553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unno, S.; Takaoka, Y.; Kishimoto, A.; Suga, H.; Kamiya, S.; Miida, Y.; Oyama, S. A Study on Dispersion Resulting from Liquefied Hydrogen Spilling. 2015. Available online: https://www.h2knowledgecentre.com/content/conference772 (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Kobayashi, H.; Muto, D.; Daimon, Y.; Umemura, Y.; Takesaki, Y.; Maru, Y.; Yagishita, T.; Nonaka, S.; Miyanabe, K. Experimental study on cryo-compressed hydrogen ignition and flame. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 5098–5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hecht, E.S.; Christopher, D.M. Validation of a reduced-order jet model for subsonic and underexpanded hydrogen jets. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 1348–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schefer, R.; Houf, W.; Williams, T. Investigation of small-scale unintended releases of hydrogen: Buoyancy effects. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 4702–4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schefer, R.; Houf, W.; Williams, T. Investigation of small-scale unintended releases of hydrogen: Momentum-dominated regime. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 6373–6384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houf, W.; Schefer, R. Analytical and experimental investigation of small-scale unintended releases of hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 1435–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, E.S.; Panda, P.P. Mixing and warming of cryogenic hydrogen releases. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 8960–8970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivkin, C.H.; Burgess, R.M.; Buttner, W.J. Regulations, Codes, and Standards (RCS) for Large Scale Hydrogen Systems. 2017. Available online: https://h2tools.org/sites/default/files/2019-07/Paper-111.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Gong, L.; Yang, S.; Han, Y.; Jin, K.; Lu, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Experimental investigation on the dispersion characteristics and concentration distribution of unignited low-temperature hydrogen release. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 160, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.H.; Chang, D.; Kim, J.S. Experimental investigation of highly pressurized hydrogen release through a small hole. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 9552–9561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, B.R.; Hecht, E.S. Dispersion of cryogenic hydrogen through high-aspect ratio nozzles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 12311–12319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannissi, S.; Venetsanos, A.; Markatos, N.; Bartzis, J. CFD modeling of hydrogen dispersion under cryogenic release conditions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 15851–15863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Liu, Y.; Wei, J.; Wu, M.; Lei, G.; Chen, H.; Lan, Y. Modeling and analysis of the flammable vapor cloud formed by liquid hydrogen spills. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 26762–26770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Hur, N.; Kang, S.; Lee, E.D.; Lee, K.B. A CFD simulation of hydrogen dispersion for the hydrogen leakage from a fuel cell vehicle in an underground parking garage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 8084–8091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashzadeh, M.; Ahmad, A.; Khan, F. Dispersion modelling and analysis of hydrogen fuel gas released in an enclosed area: A CFD-based approach. Fuel 2016, 184, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wen, J.; Chen, Z.; Dembele, S. Predicting radiative characteristics of hydrogen and hydrogen/methane jet fires using FireFOAM. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 20560–20569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirrone, D.; Makarov, D.; Molkov, V. Thermal radiation from cryogenic hydrogen jet fires. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 8874–8885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirrone, D.; Makarov, D.; Molkov, V. Simulation of thermal hazards from hydrogen under-expanded jet fire. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 8886–8892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Bie, H.; Xu, P.; Liu, P.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, X.; Zhao, L. Numerical simulation of high-pressure hydrogen jet flames during bonfire test. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Wu, M.; Liu, Y.; Lei, G.; Chen, H.; Lan, Y. CFD modeling and analysis of the influence factors of liquid hydrogen spills in open environment. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Huang, T.; Liu, C.; Chen, M.; Ji, S.; Christopher, D.M.; Li, X. Leak localization using distributed sensors and machine learning for hydrogen releases from a fuel cell vehicle in a parking garage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 1420–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Amin, M.F. Detection of Hydrogen Leakage Using Different Machine Learning Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2023 20th Learning and Technology Conference (L&T), Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 26 January 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, U.; Federica, F.; Nicola, P. Prediction of Condensed Phase Formation During an Accidental Release of Liquid Hydrogen. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2022, 91, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Large Scale Leakage of Liquid Hydrogen (LH2)–Tests Related to Bunkering and Maritime Use of Liquid Hydrogen. Technical Report. Available online: https://www.ffi.no/en/publications-archive/large-scale-leakage-of-liquid-hydrogen-lh2-tests-related-to-bunkering-and-maritime-use-of-liquid-hydrogen (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Alfarizi, M.G.; Ustolin, F.; Vatn, J.; Yin, S.; Paltrinieri, N. Towards accident prevention on liquid hydrogen: A data-driven approach for releases prediction. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 236, 109276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Dong, J.; Ren, Y. Hydrogen Safety Prediction and Analysis of Hydrogen Refueling Station Leakage Accidents and Process Using Multi-Relevance Machine Learning. World Electr. Veh. J. 2021, 12, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, R.R.; Calay, R.K.; Mustafa, M.Y.; Thakur, S. Artificial Intelligence-Driven Innovations in Hydrogen Safety. Hydrogen 2024, 5, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Kong, D.; Yu, X.; Ping, P.; Wang, G.; Peng, R.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, X. Prediction model for the evolution of hydrogen concentration under leakage in hydrogen refueling station using deep neural networks. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 702–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Oh, S.; Ma, B. Performance analysis of optimized machine learning models for hydrogen leakage and dispersion prediction via genetic algorithms. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 97, 1287–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, J.; Li, J.; Huang, X.; Xiao, F.; Wang, Q.; Usmani, A.S.; Chen, G. Hydrogen jet and diffusion modeling by physics-informed graph neural network. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 207, 114898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martvall, V.; Moberg, H.K.; Theodoridis, A.; Tomeček, D.; Ekborg-Tanner, P.; Nilsson, S.; Volpe, G.; Erhart, P.; Langhammer, C. Accelerating Plasmonic Hydrogen Sensors for Inert Gas Environments by Transformer-Based Deep Learning. Adv. Mater. 2022, 91, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Gao, W.; Bi, Y.; Bi, M.; Shi, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C.; Huang, S. A Hydrogen Concentration Evolution Prediction Method for Hydrogen Refueling Station Leakage Based on the Informer Model. Hydrogen 2024, 5, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretola, G.; Weissenbacher, M.; Vogiatzaki, K. Scientific machine learning based framework to forecast time evolving pressure signals during hydrogen leaks. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 172, 150951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizade, M.; Soltanizadeh, H.; Rahmanimanesh, M.; Sana, S.S. A review of recent advances and strategies in transfer learning. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2025, 16, 1123–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | Symbol/Units | Hydrogen (LH2) | Methane (LCH4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boiling Point | [K] | 20.3 | 111.7 |

| Density (liquid) | [kg/m3] | 70.9 | 422.6 |

| Density (gas at NTP) | [kg/m3] | 0.0899 | 0.668 |

| Latent Heat of Vaporization | [kJ/kg] | 445 | 510 |

| Specific Heat Capacity (gas) | [J/kg·K] | ∼14,300 | 2220 |

| Thermal Conductivity (liquid) | [W/m·K] | 0.104 | 0.17 |

| Viscosity (liquid) | [Pa·s] | ||

| Surface Tension | [N/m] | ||

| Expansion Ratio (liquid → gas) | – | ∼1:850 | ∼1:600 |

| Flammability Range in Air | [% vol] | 4–75 | 5–15 |

| Minimum Ignition Energy | [mJ] | ∼0.017 | ∼0.28 |

| Autoignition Temperature | [K] | ∼858 | ∼813 |

| Storage Type | Leakage Types & Challenges | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Storage | ||

| Compressed Hydrogen | Permeation, embrittlement, high-pressure leaks from valve/seal, overheating during fast filling | Composite tanks, multi-stage filling, robust seals/valves, and hydrogen sensors |

| Cryogenic Liquid Hydrogen | Boil-off, seal failure, embrittlement | High insulation, compatible materials, pressure relief valves |

| Cryo-Compressed Hydrogen | Combination of cryogenic and high-pressure stress, temperature rise during fast filling | Hybrid insulated tanks, robust materials, thermal control and protocol |

| Chemical Storage | ||

| Sorbents (e.g., MOFs) | Desorption leakage, sudden release, sorbent degradation | Encapsulation, stable sorbent temp/pressure control |

| Chemical Hydrides | Uncontrolled reaction, by-product gas leakage | Catalyst control, sealed containment, thermal control |

| Metal Hydrides | Thermal desorption leakage, fatigue cracking | Durable alloys, safe desorption control, thermal management |

| Type of Sensor | Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal | Heat transfer or combustion causes changes in temperature or resistance | Robust, fast response | High power, not selective |

| Electrochemical | Chemical reactions generate electrical signals such as current, voltage, conductivity, or impedance | Sensitive, low power, selective | Lifespan, sensitive to environment |

| Optical | Interaction with hydrogen changes light absorption, reflection, or emission | Highly precise, fast response | Expensive, complex |

| Semiconductor | Hydrogen adsorption on the sensing layer changes electrical resistance | Cheap, compact | Low selectivity, humidity sensitive |

| Acoustic | Hydrogen presence changes the resonance frequency of piezoelectric materials | Highly sensitive, fast response | Fragile, temperature sensitive |

| Sensor Type | Detection (ppm) | Response Time | Temp. (°C) | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pellistor | 1–1000 ppm | <10 s | [−20;50] | Leak detection, industrial and mining with explosive gases |

| TCD | 500–40,000 ppm | <4 s | [−20;90] | Leak detection, industrial, home safety devices |

| Potentio | 100 ppm | 10–90 s | [0;100] | Leak detection, industrial |

| Ampero | ~ 10 ppm | 20–50 s | [−20;80] | R&D |

| Raman | 500 ppm | s–min | [20;30] | Research, Lab |

| Absor/Emi | 1–100 ppm | s/min | [20;30] | Industrial hydrogen leak detection |

| FBG | 0.15–10 ppm | 1–5 s | [−30;80] | Leak detection |

| SPR | 40,000 ppm | <1 s | [−20;60] | Hydrogen leak detection in industrial |

| MOS | 100 ppm | <5 s | [80;400] | Safety devices |

| SAW | 10 ppm | <5 s | [−20;80] | Automotive, wireless sensing devices |

| QCM | 10 ppm | <5 s | Room Tempe. | Leak detection |

| Category | Methods | Principle and Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Classical ML | Decision Trees (DT) | Tree-based model. Predictions of dispersion of hydrogen. |

| Random Forests (RF) | Ensemble of decision trees. Predictions of oxygen phase changes and hydrogen concentrations. | |

| Gradient Boosting (GBR) | Ensemble of learning algorithms. Predictions of dispersion of hydrogen. | |

| Genetic Algorithms (GA) | Computing technique for optimization. Predictions of hydrogen dispersion. | |

| Deep Learning | Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | General neural network. Predictions of leak locations |

| Deep Neural Networks (DNN) | Multi-layer ANNs for complex representations. Predictions of leaks with pressure, temperature, or concentration. | |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN, CV) | Specialized ANN for Computer Vision tasks. | |

| Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN, LSTM) | Sequential/time-series modeling. Predictions of hydrogen concentration. | |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNN) | Learning from graph-structured data. Predictions of leak characteristics. | |

| Transformers | Self-attention mechanism, mainly used in NLP (Natural Language Processing). Predictions of hydrogen diffusion |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vogiatzaki, K.; Tretola, G.; Cesmat, L. Digital Twins for Cryogenic Hydrogen Safety: Integrating Computational Fluid Dynamics and Machine Learning. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040110

Vogiatzaki K, Tretola G, Cesmat L. Digital Twins for Cryogenic Hydrogen Safety: Integrating Computational Fluid Dynamics and Machine Learning. Hydrogen. 2025; 6(4):110. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040110

Chicago/Turabian StyleVogiatzaki, Konstantina, Giovanni Tretola, and Laurie Cesmat. 2025. "Digital Twins for Cryogenic Hydrogen Safety: Integrating Computational Fluid Dynamics and Machine Learning" Hydrogen 6, no. 4: 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040110

APA StyleVogiatzaki, K., Tretola, G., & Cesmat, L. (2025). Digital Twins for Cryogenic Hydrogen Safety: Integrating Computational Fluid Dynamics and Machine Learning. Hydrogen, 6(4), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040110