Membrane Depth Measurements of E Protein by 2H ESEEM Spectroscopy in Lipid Bilayers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

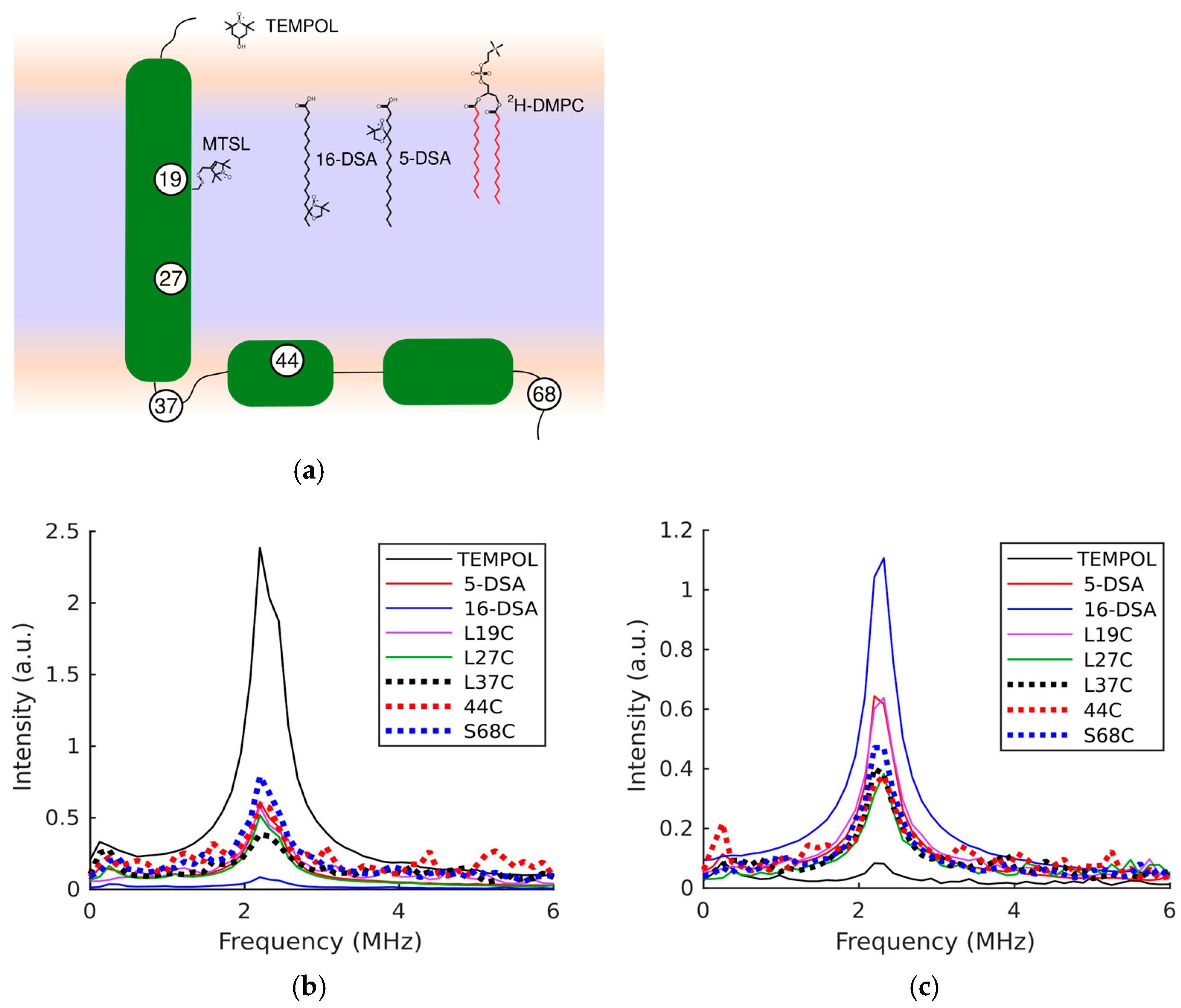

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EPR | electron paramagnetic resonance |

| ESEEM | electron spin echo envelope modulation |

| d54-DMPC | deuterated dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine |

| 5-DSA | 5-doxyl stearic acid |

| 16-DSA | 16-doxyl stearic acid |

| TEMPOL | 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-oxyl |

| CTD | C-terminal domain |

| TMD | transmembrane Domain |

| FMOC | fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl |

| MTSL | S-(1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-2,5-dihydro-1H-pyrrol-3-yl)methyl methanesulfonothioate |

| DPPC | dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine |

| LMPG | lysomyristoylphosphatidylglycerol |

| TFE | trifluoroethanol |

References

- Arya, R.; Kumari, S.; Pandey, B.; Mistry, H.; Bihani, S.C.; Das, A.; Prashar, V.; Gupta, G.D.; Panicker, L.; Kumar, M. Structural Insights into SARS-CoV-2 Proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433, 166725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duart, G.; García-Murria, M.J.; Mingarro, I. The SARS-CoV-2 Envelope (E) Protein Has Evolved towards Membrane Topology Robustness. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Biomembr. 2021, 1863, 183608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdiá-Báguena, C.; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; Alcaraz, A.; DeDiego, M.L.; Torres, J.; Aguilella, V.M.; Enjuanes, L. Coronavirus E Protein Forms Ion Channels with Functionally and Structurally-Involved Membrane Lipids. Virology 2012, 432, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yang, R.; Lee, I.; Zhang, W.; Sun, J.; Wang, W.; Meng, X. Characterization of the SARS-CoV-2 E Protein: Sequence, Structure, Viroporin, and Inhibitors. Protein Sci. 2021, 30, 1114–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeman, D.; Fielding, B.C. Coronavirus Envelope Protein: Current Knowledge. Virol. J. 2019, 16, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boson, B.; Legros, V.; Zhou, B.; Siret, E.; Mathieu, C.; Cosset, F.-L.; Lavillette, D.; Denolly, S. The SARS-CoV-2 Envelope and Membrane Proteins Modulate Maturation and Retention of the Spike Protein, Allowing Assembly of Virus-like Particles. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wölk, C.; Shen, C.; Hause, G.; Surya, W.; Torres, J.; Harvey, R.D.; Bello, G. Membrane Condensation and Curvature Induced by SARS-CoV-2 Envelope Protein. Langmuir ACS J. Surf. Colloids 2024, 40, 2646–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruch, T.R.; Machamer, C.E. The Coronavirus E Protein: Assembly and Beyond. Viruses 2012, 4, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duart, G.; García-Murria, M.J.; Grau, B.; Acosta-Cáceres, J.M.; Martínez-Gil, L.; Mingarro, I. SARS-CoV-2 Envelope Protein Topology in Eukaryotic Membranes. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 200209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.; Parthasarathy, K.; Lin, X.; Saravanan, R.; Kukol, A.; Liu, D.X. Model of a Putative Pore: The Pentameric Alpha-Helical Bundle of SARS Coronavirus E Protein in Lipid Bilayers. Biophys. J. 2006, 91, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surya, W.; Li, Y.; Torres, J. Structural Model of the SARS Coronavirus E Channel in LMPG Micelles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Biomembr. 2018, 1860, 1309–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros-Silva, J.; Dregni, A.J.; Somberg, N.H.; Duan, P.; Hong, M. Atomic Structure of the Open SARS-CoV-2 E Viroporin. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadi9007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandala, V.S.; McKay, M.J.; Shcherbakov, A.A.; Dregni, A.J.; Kolocouris, A.; Hong, M. Structure and Drug Binding of the SARS-CoV-2 Envelope Protein Transmembrane Domain in Lipid Bilayers. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dregni, A.J.; McKay, M.J.; Surya, W.; Queralt-Martin, M.; Medeiros-Silva, J.; Wang, H.K.; Aguilella, V.; Torres, J.; Hong, M. The Cytoplasmic Domain of the SARS-CoV-2 Envelope Protein Assembles into a β-Sheet Bundle in Lipid Bilayers. J. Mol. Biol. 2023, 435, 167966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surya, W.; Torres, J. Oligomerization-Dependent Beta-Structure Formation in SARS-CoV-2 Envelope Protein. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, I.D.; McCarrick, R.M.; Lorigan, G.A. Use of Electron Paramagnetic Resonance To Solve Biochemical Problems. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 5967–5984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, I.D.; Lorigan, G.A. Biophysical EPR Studies Applied to Membrane Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. Biophys. 2015, 5, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorigan, G.A.; Britt, R.D.; Kim, J.H.; Hille, R. Electron Spin Echo Envelope Modulation Spectroscopy of the Molybdenum Center of Xanthine Oxidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1994, 1185, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartucci, R.; Guzzi, R.; Esmann, M.; Marsh, D. Water Penetration Profile at the Protein-Lipid Interface in Na,K-ATPase Membranes. Biophys. J. 2014, 107, 1375–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiff, T.; Kevan, L. Electron Spin Echo Modulation Studies of Doxylstearic Acid Spin Probes in Frozen Vesicles: Interaction of the Spin Probe with Water-D2 and Effects of Cholesterol Addition. J. Phys. Chem. 1989, 93, 1572–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erilov, D.A.; Bartucci, R.; Guzzi, R.; Shubin, A.A.; Maryasov, A.G.; Marsh, D.; Dzuba, S.A.; Sportelli, L. Water Concentration Profiles in Membranes Measured by ESEEM of Spin-Labeled Lipids. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 12003–12013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Mayo, D.J.; Sahu, I.D.; Zhou, A.; Zhang, R.; McCarrick, R.M.; Lorigan, G.A. Determining the Secondary Structure of Membrane Proteins and Peptides Via Electron Spin Echo Envelope Modulation (ESEEM) Spectroscopy. Methods Enzymol. 2015, 564, 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Hess, J.; Sahu, I.D.; FitzGerald, P.G.; McCarrick, R.M.; Lorigan, G.A. Probing the Local Secondary Structure of Human Vimentin with Electron Spin Echo Envelope Modulation (ESEEM) Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 12321–12326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmieli, R.; Papo, N.; Zimmermann, H.; Potapov, A.; Shai, Y.; Goldfarb, D. Utilizing ESEEM Spectroscopy to Locate the Position of Specific Regions of Membrane-Active Peptides within Model Membranes. Biophys. J. 2006, 90, 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, I.D.; Lorigan, G.A. Site-Directed Spin Labeling EPR for Studying Membrane Proteins. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 3248289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartucci, R.; Erilov, D.A.; Guzzi, R.; Sportelli, L.; Dzuba, S.A.; Marsh, D. Time-Resolved Electron Spin Resonance Studies of Spin-Labelled Lipids in Membranes. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2006, 141, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.; McCarrick, R.; Lorigan, G.A. Comparison of Lipid Dynamics and Permeability in Styrene-Maleic Acid and Diisobutylene-Maleic Acid Copolymer Lipid Nanodiscs by Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. JBIC J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 30, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, D. Membrane Water-Penetration Profiles from Spin Labels. Eur. Biophys. J. 2002, 31, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartucci, R.; Guzzi, R.; Marsh, D.; Sportelli, L. Intramembrane Polarity by Electron Spin Echo Spectroscopy of Labeled Lipids. Biophys. J. 2003, 84, 1025–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, D.; Zhou, A.; Sahu, I.; McCarrick, R.; Walton, P.; Ring, A.; Troxel, K.; Coey, A.; Hawn, J.; Emwas, A.-H.; et al. Probing the Structure of Membrane Proteins with Electron Spin Echo Envelope Modulation Spectroscopy. Protein Sci. 2011, 20, 1100–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroncke, B.M.; Horanyi, P.S.; Columbus, L. Structural Origins of Nitroxide Side Chain Dynamics on Membrane Protein α-Helical Sites. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 10045–10060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morris, A.K.; McCarrick, R.M.; Lorigan, G.A. Membrane Depth Measurements of E Protein by 2H ESEEM Spectroscopy in Lipid Bilayers. Biophysica 2025, 5, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica5040058

Morris AK, McCarrick RM, Lorigan GA. Membrane Depth Measurements of E Protein by 2H ESEEM Spectroscopy in Lipid Bilayers. Biophysica. 2025; 5(4):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica5040058

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorris, Andrew K., Robert M. McCarrick, and Gary A. Lorigan. 2025. "Membrane Depth Measurements of E Protein by 2H ESEEM Spectroscopy in Lipid Bilayers" Biophysica 5, no. 4: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica5040058

APA StyleMorris, A. K., McCarrick, R. M., & Lorigan, G. A. (2025). Membrane Depth Measurements of E Protein by 2H ESEEM Spectroscopy in Lipid Bilayers. Biophysica, 5(4), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica5040058