Comprehensive Experimental Analysis of Tear Fluid Composition and Structure by Using Novel Physical Methods with Diagnostic Potential for Inflammatory Diseases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

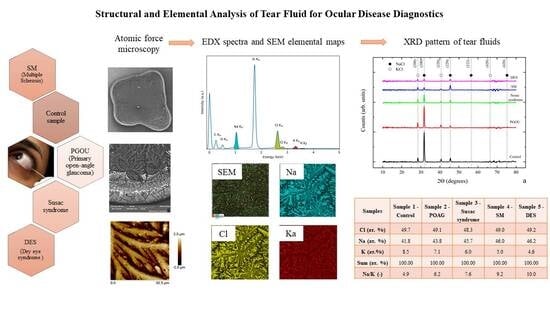

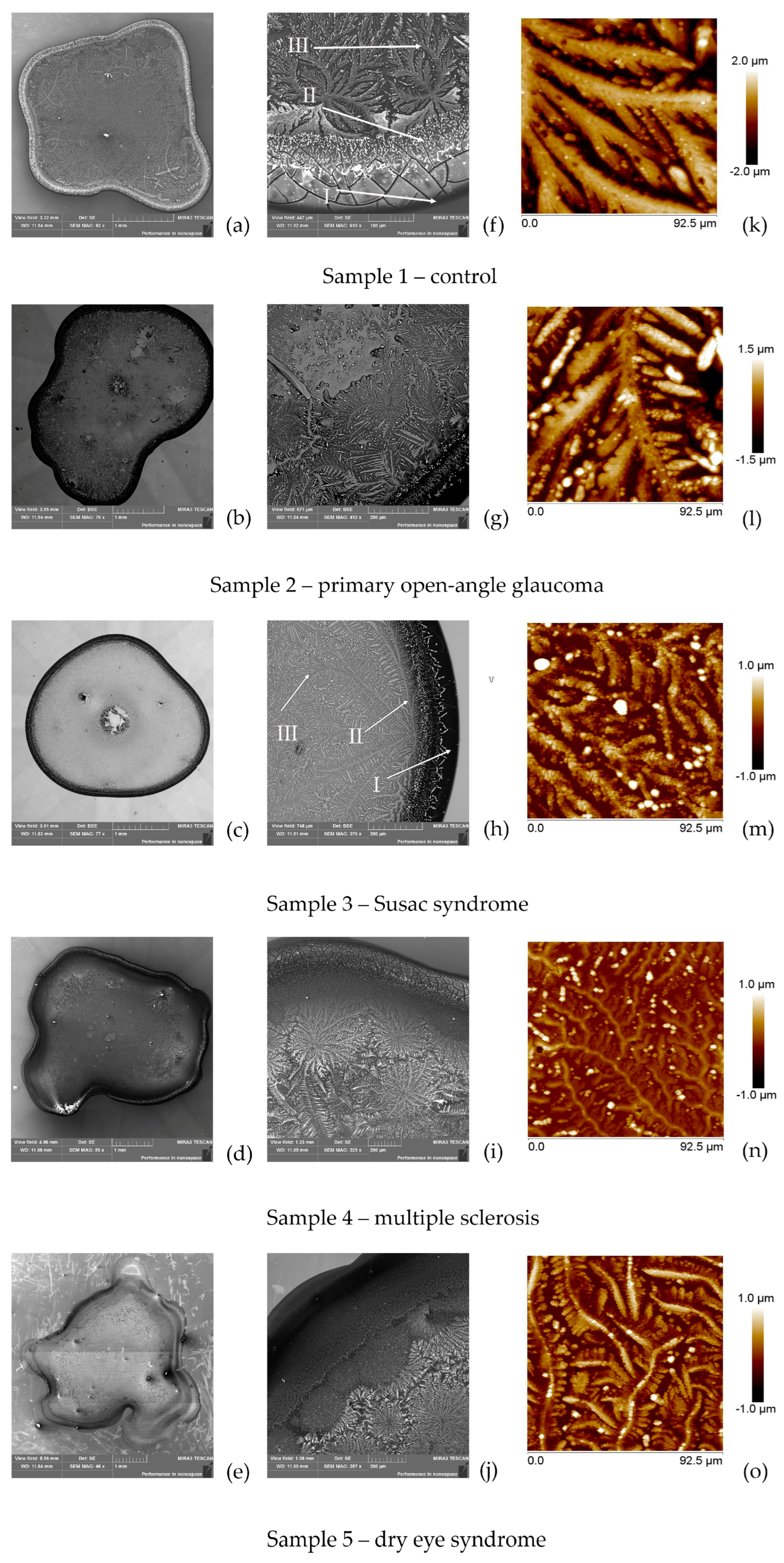

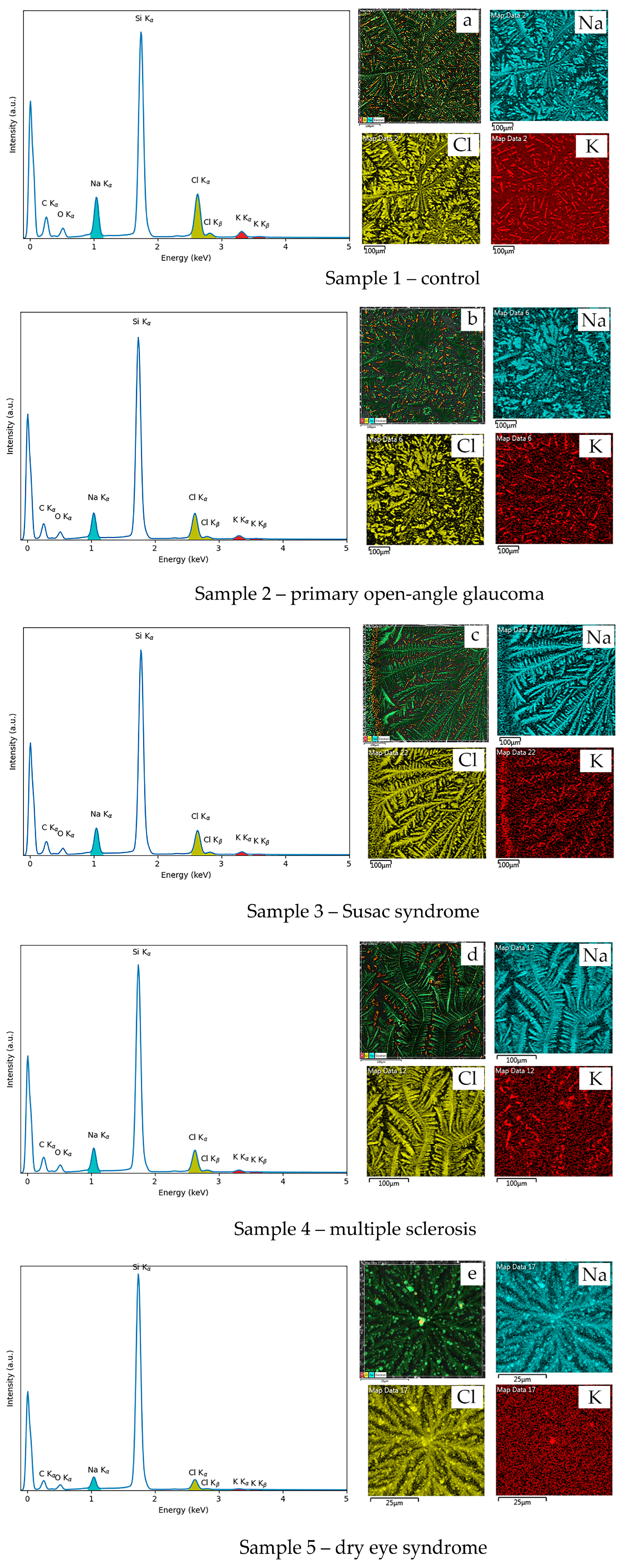

2.1. EDX and AFM Analysis of Tear Fluid Microdesiccates from Patients with Inflammatory and Neurodegenerative Diseases

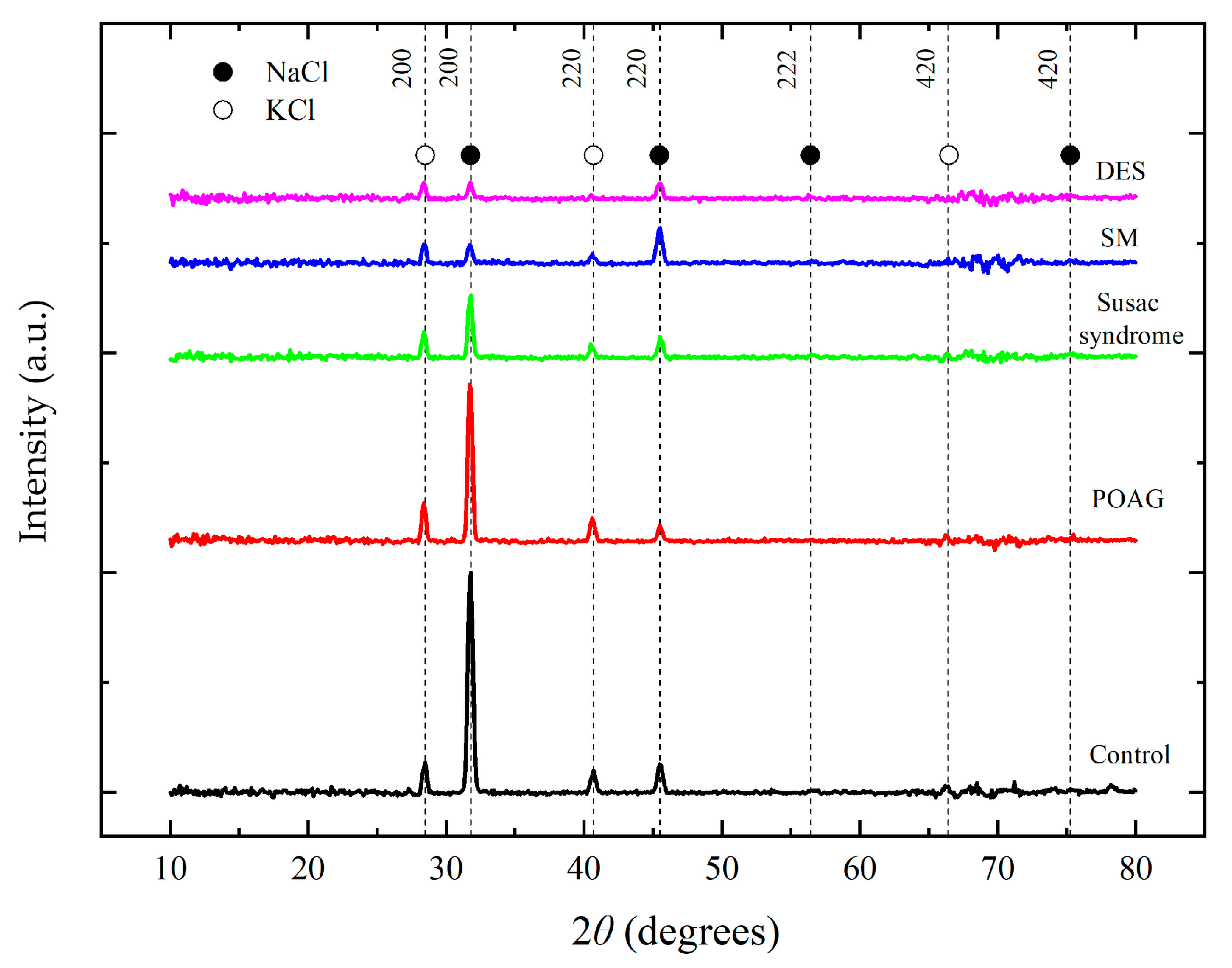

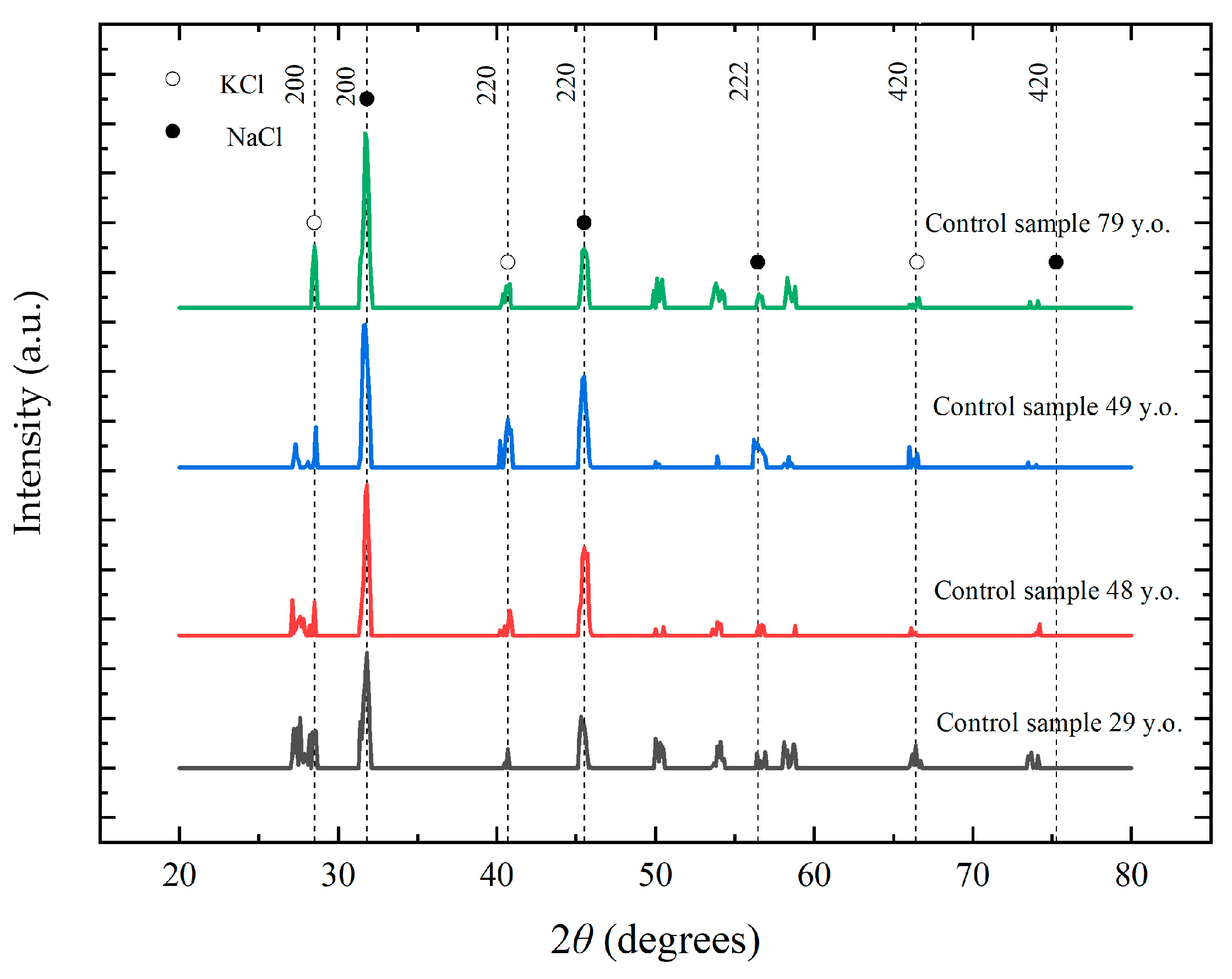

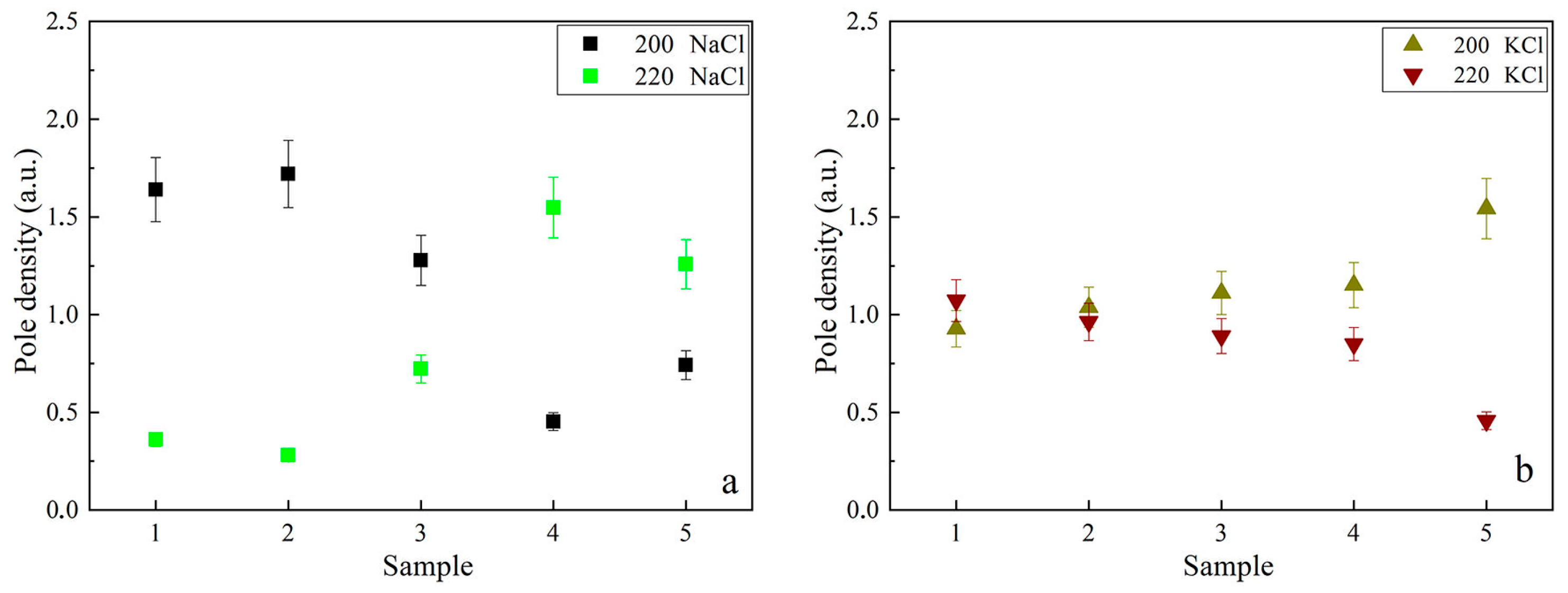

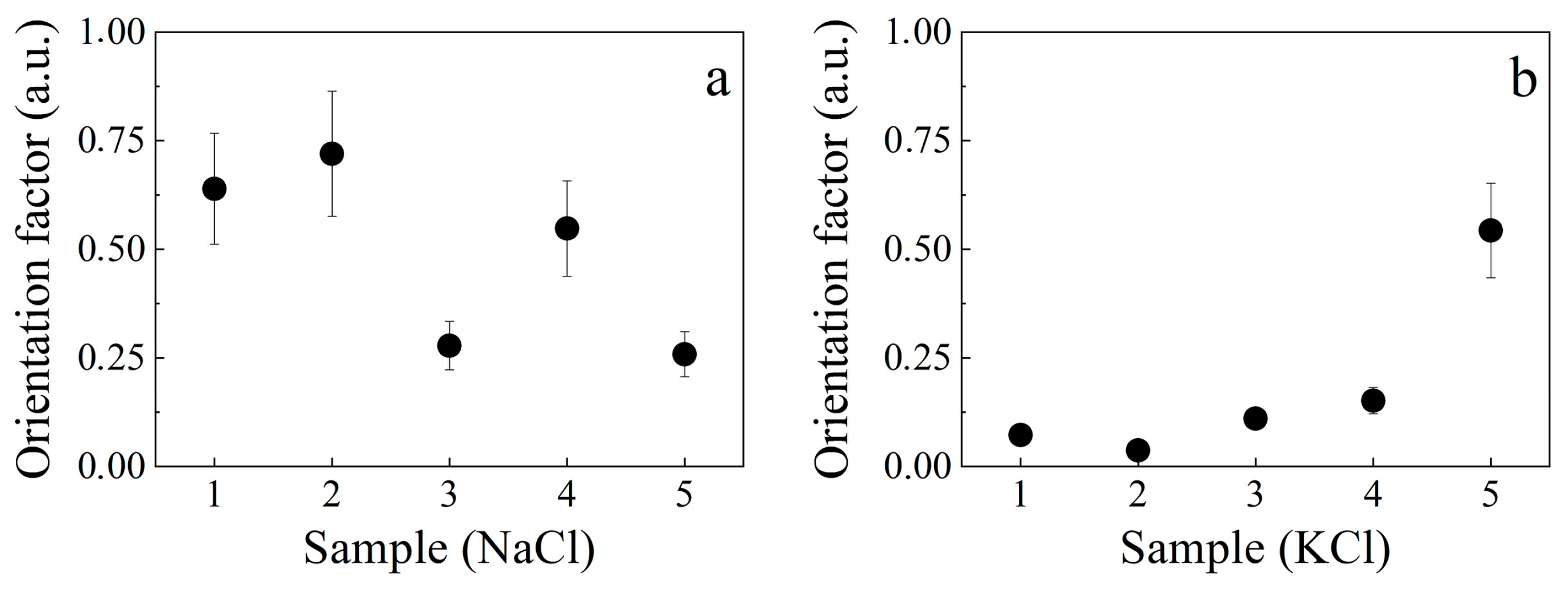

2.2. Analysis of Tear Fluid Crystallization Patterns in Ocular Diseases Using X-Ray Diffraction

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

| AFM | Atomic Force Microscopy |

| EDX | Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| POAG | Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma |

| SM | Multiple Sclerosis |

| DES | Dry Eye Syndrome |

| Na+/K+-ATPase | The sodium–potassium pump |

| Na+ | Sodium Ion |

| K+ | Potassium Ion |

| NaCl | Sodium Chloride |

| KCl | Potassium Chloride |

| C | Carbon |

| Cl | Chlorine |

| O | Oxygen |

| Pi | Pole Density |

| f | Orientation Factor |

| ω | Incidence angle |

| Imax | Maximum intensities |

| Iint | Integral intensities |

References

- Adigal, S.S.; Rizvi, A.; Rayaroth, N.V.; John, R.V.; Barik, A.; Bhandari, S.; George, S.D.; Lukose, J.; Kartha, V.B.; Chidangil, S. Human Tear Fluid Analysis for Clinical Applications: Progress and Prospects. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2021, 21, 1077–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravishankar, P.; Daily, A. Tears as the Next Diagnostic Biofluid: A Comparative Study between Ocular Fluid and Blood. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmada, A.; Shippy, S.A. Tear Analysis as the Next Routine Body Fluid Test. Eye 2020, 34, 1731–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflugfelder, S.C.; Stern, M.E. Biological Functions of Tear Film. Exp. Eye Res. 2020, 197, 108115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudi, S. Biochemistry of Human Tear Film: A Review. Exp. Eye Res. 2020, 220, 109101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Thun und Hohenstein-Blaul, N.; Funke, S.; Grus, F.H. Tears as a Source of Biomarkers for Ocular and Systemic Diseases. Exp. Eye Res. 2013, 117, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Willcox, M.D.; Madigan, M.C.; Wasinger, V.; Schiller, B.; Walsh, B.J.; Graham, P.H.; Kearsley, J.H.; Li, Y. Chapter Four—Tear Fluid Protein Biomarkers. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2013, 62, 151–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, K.M.; Ajithaprasad, S.; N, M.; Pavithran, S.; Chidangil, S.; Lukose, J. Raman Spectroscopy Assisted Tear Analysis: A Label-Free, Optical Approach for Noninvasive Disease Diagnostics. Exp. Eye Res. 2024, 243, 109913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, P.; Tabasumma, N.; Snigdha, N.N.; Siam, N.H.; Panduru, R.V.N.R.S.; Azam, S.; Hannan, J.M.A.H.; Abdel-Wahab, Y.H.A. Diabetic Retinopathy: An Overview on Mechanisms, Pathophysiology, and Pharmacotherapy. Diabetology 2022, 3, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, N.; Funke, S.; Kegel, M.; Scieranski, M.; Pfeiffer, N.; Grus, F.H. In-Depth Protein Profiling and Identification of Tear Fluid Biomarkers in the Glaucomatous Eye. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mitchell, W.; Elze, T.; Zebardast, N. Association Between Diabetes, Diabetic Retinopathy, and Glaucoma. Diabetes Ther. 2021, 21, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerlingo, C.; Lisitskiy, M.; Lepore, M.; Portaccio, M.; Montorio, D.; Del Prete, S.; Cennamo, G. Characterization of Human Tear Fluid by Means of Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Sensors 2019, 19, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomečková, V.; Tkáčiková, S.; Talian, I.; Kondrakhova, D.; Zakutanská, K.; Fabriciová, G.; Hovan, A.; Skirková, M.; Komanický, V.; Tomašovičová, N. Experimental Analysis of Tear Fluid and Its Processing for the Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis. Sensors 2023, 23, 5251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuens, J.Y.; Sze, Y.H.; Bian, J.F.; Lam, T.C. Critical Role of Mass Spectrometry Proteomics in Tear Biomarker Discovery for Multifactorial Ocular Diseases (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 47, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Hu, L.; Jiao, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, K.; Li, L.; Fan, Y. A Hydrogel-Based Biosensor for Stable Detection of Glucose. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 221, 114908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nättinen, J.; Aapola, U.; Nukareddy, P.; Uusitalo, H. Clinical Tear Fluid Proteomics—A Novel Tool in Glaucoma Research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winiarczyk, M.; Biela, K.; Michalak, K.; Winiarczyk, D.; Mackiewicz, J. Changes in Tear Proteomic Profile in Ocular Diseases. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagan, S.; Martin, E.; Enríquez-de-Salamanca, A. Tear Fluid Biomarkers in Ocular and Systemic Disease: Potential Use for Predictive, Preventive, and Personalised Medicine. EPMA J. 2016, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spörri, L.; Uldry, A.-C.; Kreuzer, M.; Herzog, E.L.; Zinkernagel, M.S.; Unterlauft, J.D.; Zysset-Burri, D.C. Exploring the Ocular Surface Microbiome and Tear Proteome in Glaucoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qiu, P.; Shen, T. Gut Microbiota and Eye Diseases: A Review. Medicine 2024, 103, e39866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yu, H.; Xu, L.; Yu, M.; Zhang, Y. Relationship Between Gut Microbiota and Multiple Sclerosis: A Scientometric Visual Analysis from 2010 to 2023. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1451742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Omura, S.; Khadka, S.; Sato, F.; Park, A.-M.; Rimal, S.; Tsunoda, I. Gut Microbiota in a Viral Model of Multiple Sclerosis: Modulation and Pitfalls by Oral Antibiotic Treatment. Cells 2025, 14, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotovat-Ahmadi, N.; Siddiqui, O.; Ong, J.; Thanitcul, C.; Reinhardt, C.; Cologna, S.M.; Aakalu, V.K. The Ocular Surface Tear Film as a Biomarker for Systemic Health. Ocul. Surf. 2025, 37, 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, C.R.; Feulner, L.; Djonov, V.; Pavlovic, D.; Volarevic, V. The Molecular Mechanisms Responsible for Tear Hyperosmolarity-Induced Pathological Changes in the Eyes of Dry Eye Disease Patients. Cells 2023, 12, 2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Castañeda, S.M.; Cordova-Gallardo, J.; Chavez-Pacheco, J.L.; Ramírez-Mejía, M.M.; Rivera-Espinosa, L.; Méndez-Sánchez, N. Bilirubin Molecular Species Play an Important Role in the Pathophysiology of Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamhane, M.; Cabrera-Ghayouri, S.; Abelian, G.; Viswanath, V. Review of Biomarkers in Ocular Matrices: Challenges and Opportunities. Pharm. Res. 2019, 36, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajčíková, K.; Semančíková, E.; Zakutanská, K.; Kondrakhova, D.; Mašlanková, J.; Stupák, M.; Stupák, M.; Talian, I.; Tomašovičová, N.; Kimáková, T.; et al. Tear Fluid Biomarkers in Major Depressive Disorder: Potential of Spectral Methods in Biomarker Discovery. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 138, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondrakhova, D.; Unger, M.; Stadler, H.; Zakutanská, K.; Tomašovičová, N.; Tomečková, V.; Horák, J.; Kimakova, T.; Komanický, V. Determination of Diabetes Mellitus Disease Markers in Tear Fluid by Photothermal AFM-IR Analysis. Nanomedicine 2025, 64, 102803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Solís, R.; Traipe-Castro, L.; Salinas-Toro, D.; Srur, M.; Toledo-Araya, H. Microdesiccates Produced from Normal Human Tears Display Four Distinctive Morphological Components. Biol. Res. 2013, 46, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almutleb, E.S.; El-Hiti, G.A.; Al-Dawas, H.A.; Alanzi, M.K.; Alquwayi, M.; Alotaibi, A.G.; Baashen, M.A.; Altoaimi, B.H.; Alanazi, S.A.; Masmali, A.M. Effect of Monovalent Electrolyte Solutions on the Human Tear Fering Pattern. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traipe-Castro, L.; Salinas-Toro, D.; López, D.; Zanolli, M.; Srur, M.; Valenzuela, F.; Cáceres, A.; Toledo-Araya, H.; López-Solís, R. Dynamics of Tear Fluid Desiccation on a Glass Surface: A Contribution to Tear Quality Assessment. Biol. Res. 2014, 47, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traipe Salas, F.; Traipe Castro, L.; Salinas Toro, D.; López, D.; Valenzuela, F.; Cartes, C.; Toledo Araya, H.; Pérez, C.; López Solís, R. Progress in Tear Microdesiccate Analysis by Combining Various Transmitted Light Microscope Techniques. Biol. Res. 2016, 49, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golding, T.R.; Baker, A.T.; Rechberger, J.; Brennan, N.A. X-ray and Scanning Electron Microscopic Analysis of the Structural Composition of Tear Ferns. Cornea 1994, 13, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogbe, O.; Liotet, S. An Interesting Use of the Study of Tear Ferning Patterns in Contactology. Ophthalmologica 1987, 194, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirahanchi, Y.; Jessu, R.; Aeddula, N.R. Physiology, Sodium Potassium Pump. In StatPearls; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537088/ (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Almássy, J.; Diszházi, G.; Skaliczki, M.; Márton, I.; Magyar, Z.É.; Nánási, P.P.; Yule, D.I. Expression of BK Channels and Na+-K+ Pumps in the Apical Membrane of Lacrimal Acinar Cells Suggests a New Molecular Mechanism for Primary Tear-Secretion. Ocul. Surf. 2019, 17, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Mou, Y.; Yuan, K.; Huang, X.; Jin, X. Advances in Dry Eye Disease Examination Techniques. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 826530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekweremadu, E.N.; Ezeh, C.O. Tear and Serum Electrolyte Concentrations as a Biomarker in Primary Glaucoma Subjects. Life Res. 2021, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok, N.; Khamar, P.; D’Souza, S.; Gijs, M.; Ghosh, A.; Sethu, S.; Shetty, R. Ion Channels in Dry Eye Disease. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 71, 1215–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, R.M.; El-Salamouni, N.S.; El-Kamel, A.H.; El-Gamal, S.S. Lipid-Based Nanocarriers for Ocular Drug Delivery. In Nanostructures for Drug Delivery; Micro and Nano Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 495–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, E.S.; Cil, O.; Verkman, A.S.; Pasricha, N.D. Ocular Surface Ion Transport and Dry Eye Disease. Curr. Ophthalmol. Rep. 2022, 10, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarmout, M.; Xiao, Y.; Hu, X.; Rakhmetova, A.; Koole, L.H. A Novel Approach to Achieve Semi-Sustained Drug Delivery to the Eye through Asymmetric Loading of Soft Contact Lenses. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD). Powder Diffraction File (PDF-2). Available online: https://www.icdd.com/pdf-2/ (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Park, D.; Jung, Y. Atomic-Scale Understanding of Alkali Metal Cation Effects on Electro-Catalytic Reactions. Chem. Catal. 2024, 4, 100823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekweremadu, E.N.; Eze, C.O.; Kamah, J.M. Tear Electrolytes Concentration in Hospital-Derived African Subjects. J. Ophthalmic Res. Ocul. Care 2021, 4, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Singh, N.K. Inflammation and Retinal Degenerative Diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2022, 18, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusifov, T.N.; Abduragimov, A.R.; Narsinh, K.; Gasymov, O.K.; Glasgow, B.J. Tear Lipocalin is the Major Endonuclease in Tears. Mol. Vis. 2008, 14, 180–188. Available online: http://www.molvis.org/molvis/v14/a23 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Liu, H.; Begley, C.; Chen, M.; Bradley, A.; Bonanno, J.; McNamara, N.A.; Nelson, J.D.; Simpson, T. A Link Between Tear Instability and Hyperosmolarity in Dry Eye. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009, 50, 3671–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, A.M.; Senchyna, M.; Argüeso, P. Differential Contribution of Hypertonic Electrolytes to Corneal Epithelial Dysfunction. Exp. Eye Res. 2012, 100, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, B.E. X-Ray Diffraction; Dover: New York, NY, USA, 1990; p. 253. [Google Scholar]

- Umansky, Y.S. Crystallography, X-Ray Photography and Electron Microscopy; Metallurgy: Moscow, Russia, 1982; p. 632. [Google Scholar]

- Rajan, A.; Vishnu, J.; Shankar, B. Tear-Based Ocular Wearable Biosensors for Human Health Monitoring. Biosensors 2024, 14, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzini, E.; Santambrogio, C.; De Palma, A.; Mauri, P.; Tavazzi, S.; Grandori, R. Mass Spectrometry-Based Tear Proteomics for Noninvasive Biomarker Discovery. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2022, 41, 842–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nättinen, J.; Jylhä, A.; Aapola, U.; Enríquez-de-Salamanca, A.; Pinto-Fraga, J.; López-Miguel, A.; González-García, M.J.; Stern, M.E.; Calonge, M.; Zhou, L.; et al. Topical Fluorometholone Treatment and Desiccating Stress Change Inflammatory Protein Expression in Tears. Ocul. Surf. 2018, 16, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Elemental Composition | Sample 1— Control | Sample 2— POAG | Sample 3— Susac Syndrome | Sample 4—SM | Sample 5—DES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 53.9 | 49.8 | 47.6 | 48.9 | 41.9 |

| Si | 22.1 | 29.5 | 32.1 | 31.2 | 42.9 |

| O | 10.0 | 9.4 | 8.8 | 9.8 | 8.7 |

| Cl | 7.0 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 4.9 | 3.2 |

| Na | 5.9 | 4.9 | 5.3 | 4.6 | 3.0 |

| K | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Na/K | 4.9 | 6.1 | 7.6 | 9.2 | 10.0 |

| Samples | Sample 1— Control | Sample 2— POAG | Sample 3— Susac Syndrome | Sample 4—SM | Sample 5—DES | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reflection | 2θ (deg) | Integral intensity, Iint (cps·deg) | ||||

| NaCl 200 | 31.70 | 2073.00 | 1479.00 | 582.00 | 161.00 | 139.00 |

| NaCl 220 | 45.50 | 265.00 | 140.00 | 191.00 | 320.00 | 137.00 |

| KCl 200 | 28.40 | 276.00 | 352.00 | 237.00 | 169.00 | 142.00 |

| KCl 220 | 40.60 | 205.00 | 210.00 | 122.00 | 80.00 | 27.00 |

| Samples | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | |

| Reflection | 2θ (deg) | Normalized Intensity (within pattern, %) | ||||

| NaCl 200 | 31.70 | 1.00 | 0.71 | 0.28 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| NaCl 220 | 45.50 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.07 |

| KCl 200 | 28.40 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| KCl 220 | 40.60 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| KCl fraction | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.36 | |

| NaCl fraction QNaCl = 1 − QKCl | 0.85 | 0.74 | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.66 | |

| Sample texture | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.67 | 0.55 | 0.41 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kondrakhova, D.; Tomečková, V.; Dobrozhan, O.; Milkovič, O.; You, H.; Kimáková, T.; Komanický, V. Comprehensive Experimental Analysis of Tear Fluid Composition and Structure by Using Novel Physical Methods with Diagnostic Potential for Inflammatory Diseases. Biophysica 2025, 5, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica5040048

Kondrakhova D, Tomečková V, Dobrozhan O, Milkovič O, You H, Kimáková T, Komanický V. Comprehensive Experimental Analysis of Tear Fluid Composition and Structure by Using Novel Physical Methods with Diagnostic Potential for Inflammatory Diseases. Biophysica. 2025; 5(4):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica5040048

Chicago/Turabian StyleKondrakhova, Daria, Vladimíra Tomečková, Oleksandr Dobrozhan, Ondrej Milkovič, Hoydoo You, Tatiana Kimáková, and Vladimír Komanický. 2025. "Comprehensive Experimental Analysis of Tear Fluid Composition and Structure by Using Novel Physical Methods with Diagnostic Potential for Inflammatory Diseases" Biophysica 5, no. 4: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica5040048

APA StyleKondrakhova, D., Tomečková, V., Dobrozhan, O., Milkovič, O., You, H., Kimáková, T., & Komanický, V. (2025). Comprehensive Experimental Analysis of Tear Fluid Composition and Structure by Using Novel Physical Methods with Diagnostic Potential for Inflammatory Diseases. Biophysica, 5(4), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica5040048