Damage Mechanism and Sensitivity Analysis of Cement Sheath Integrity in Shale Oil Wells During Multi-Stage Fracturing Based on the Discrete Element Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Meso-Parameter Setting of Discrete Element Model

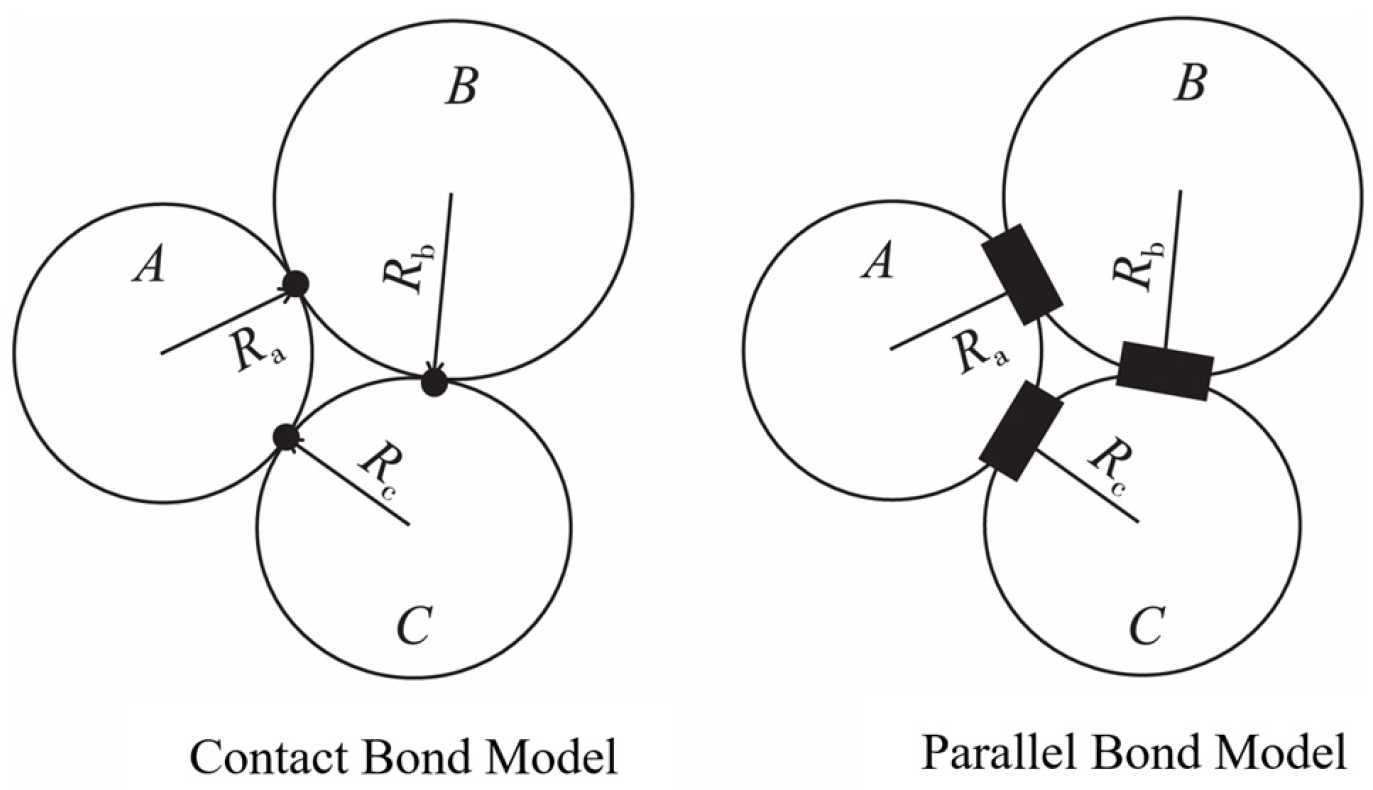

2.1. Discrete Element Contact Model

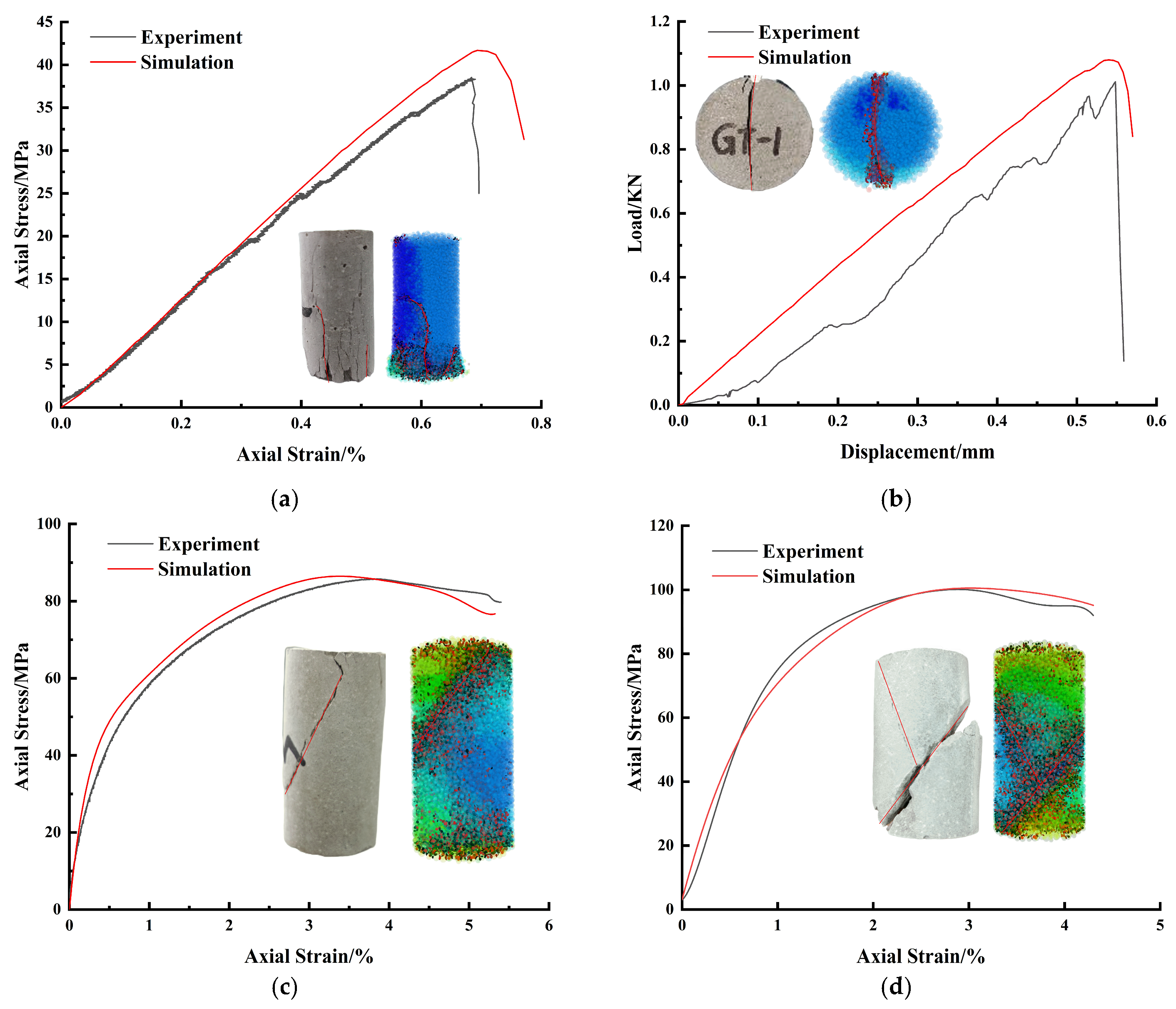

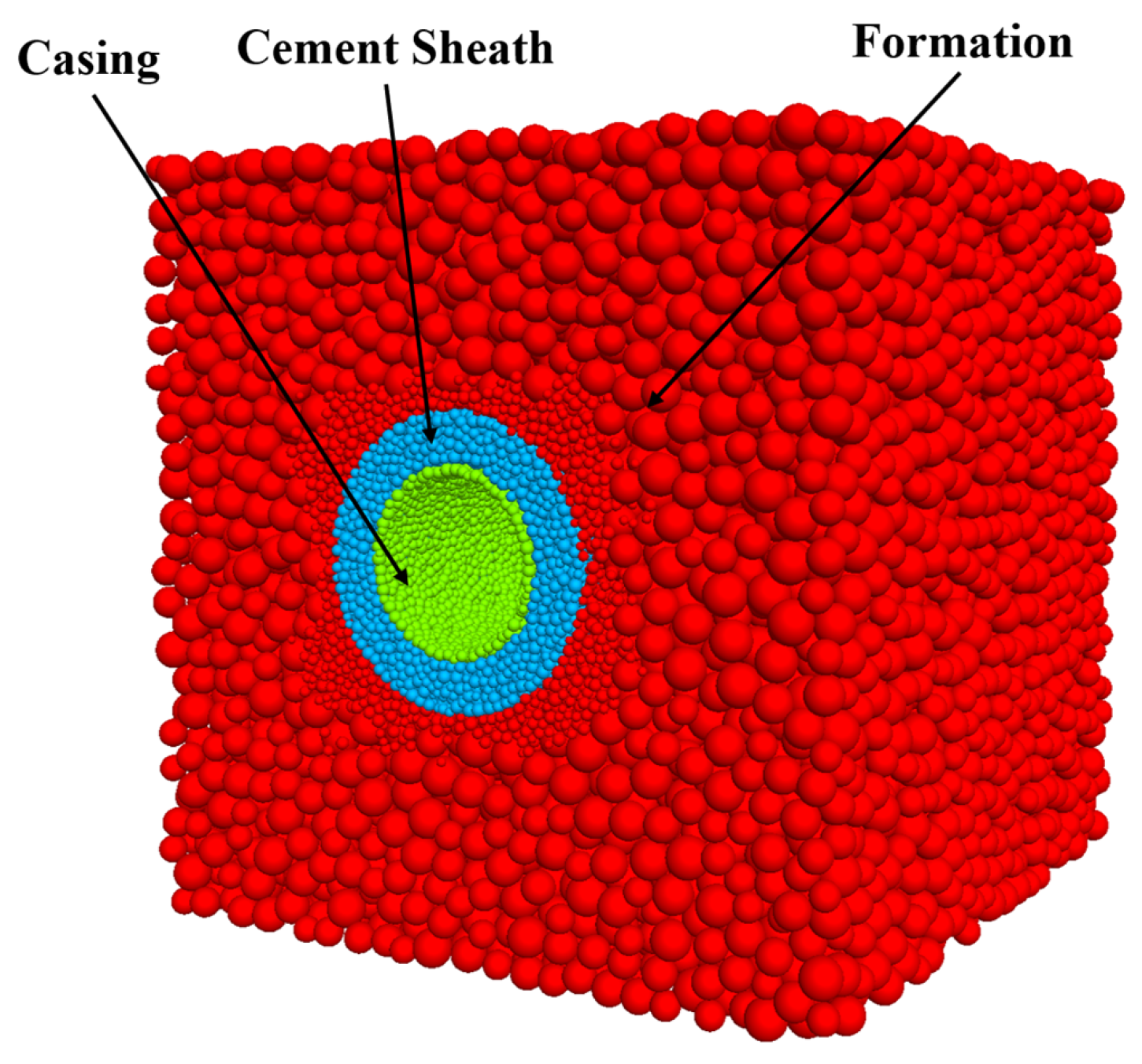

2.2. Meso-Parameters of Discrete Element Model

3. Establishment and Validation of Discrete Element Numerical Model

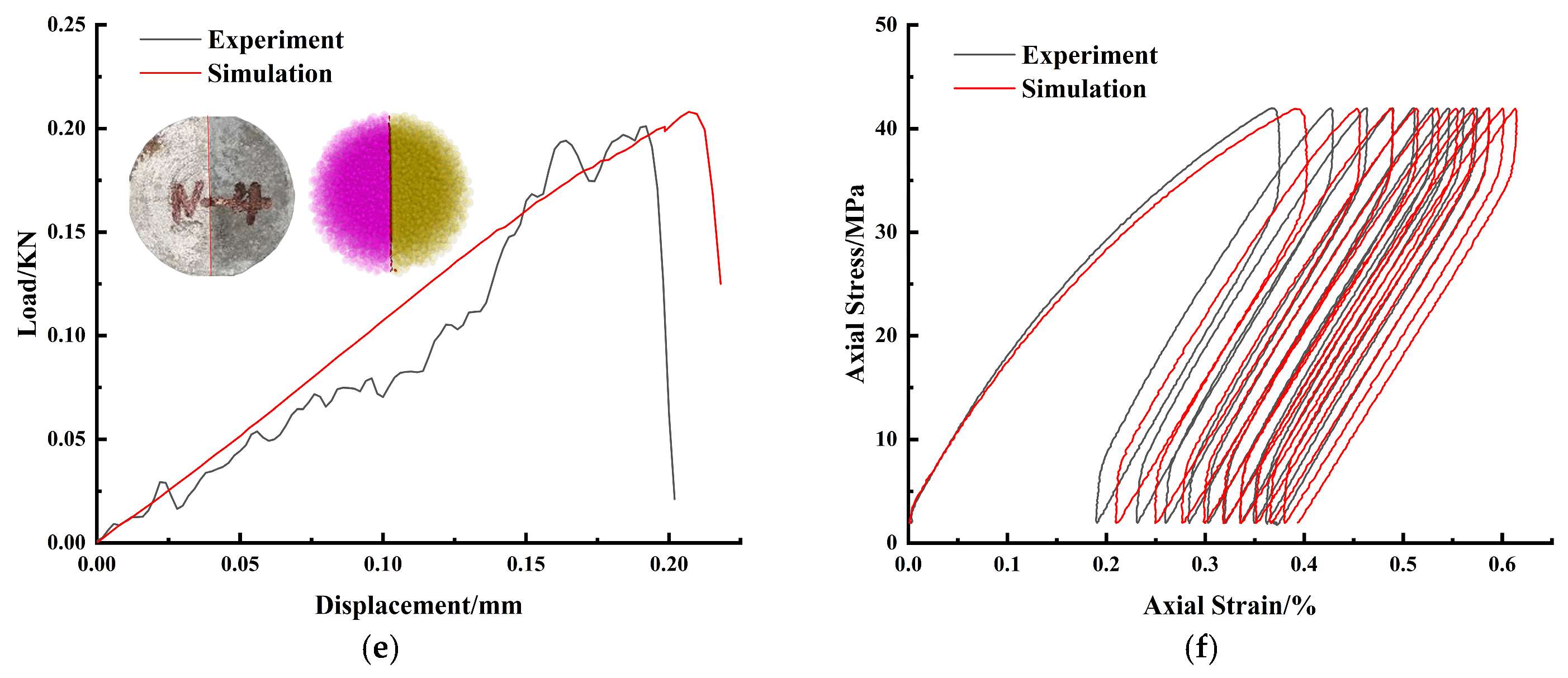

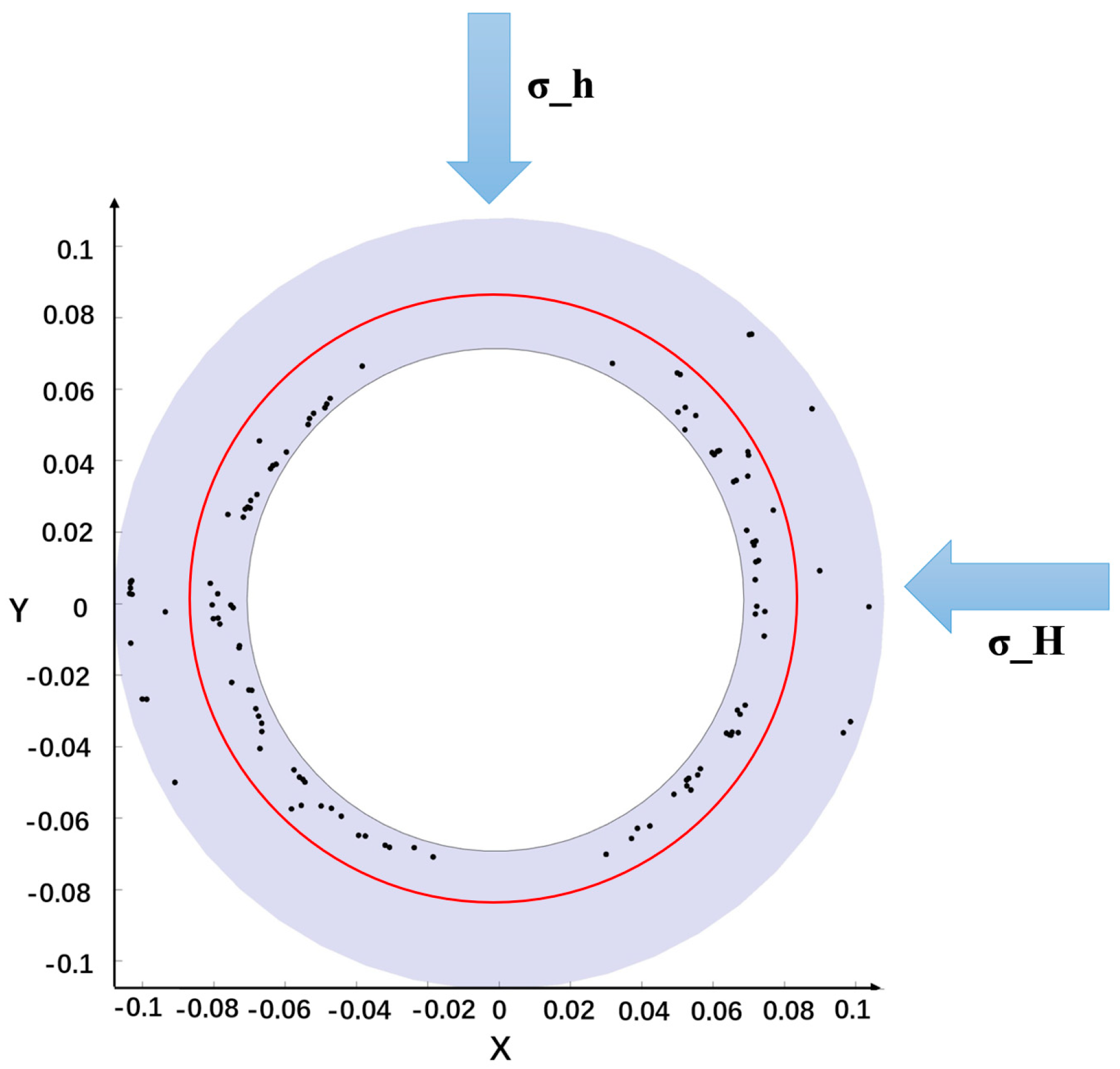

3.1. Model Construction

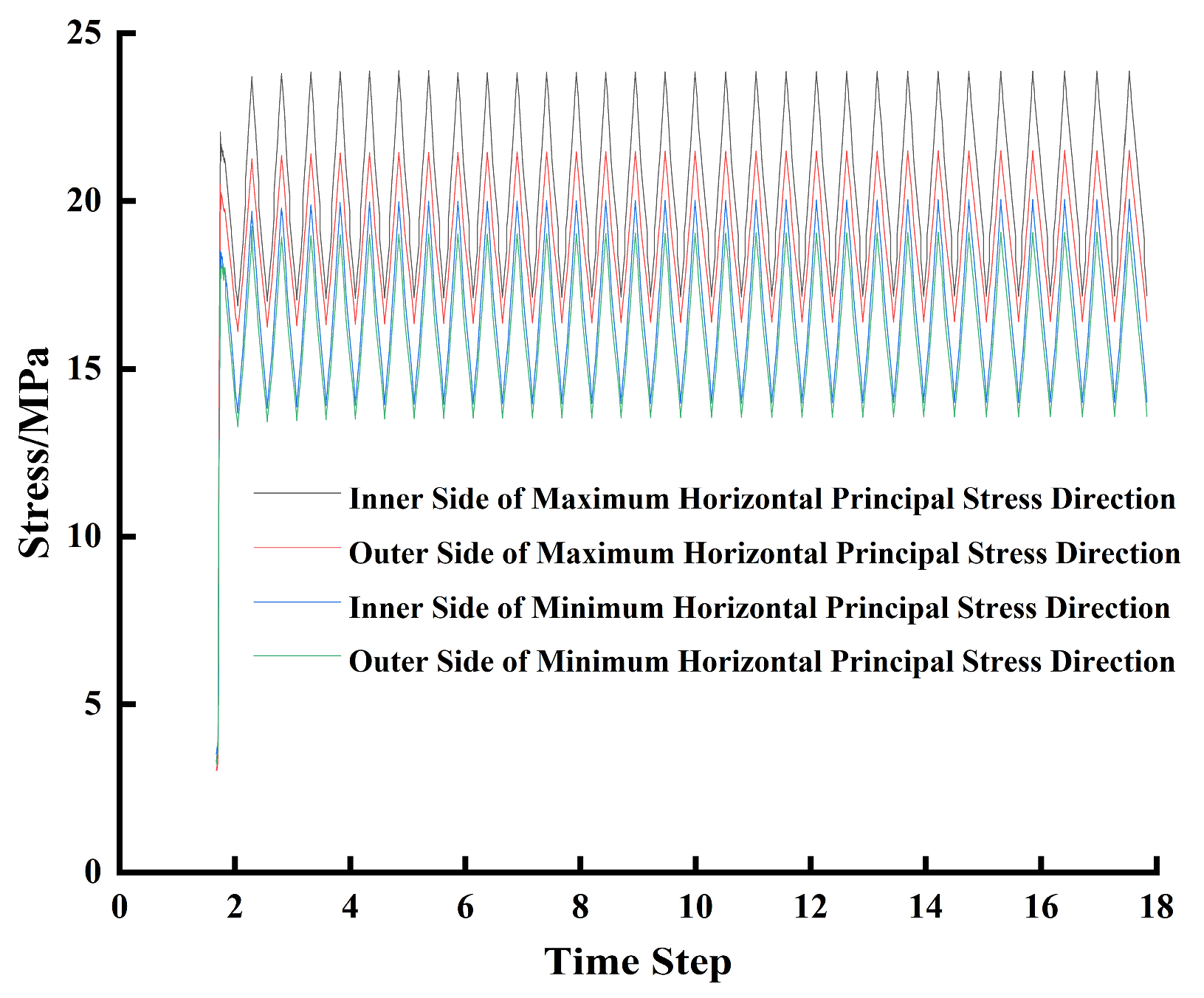

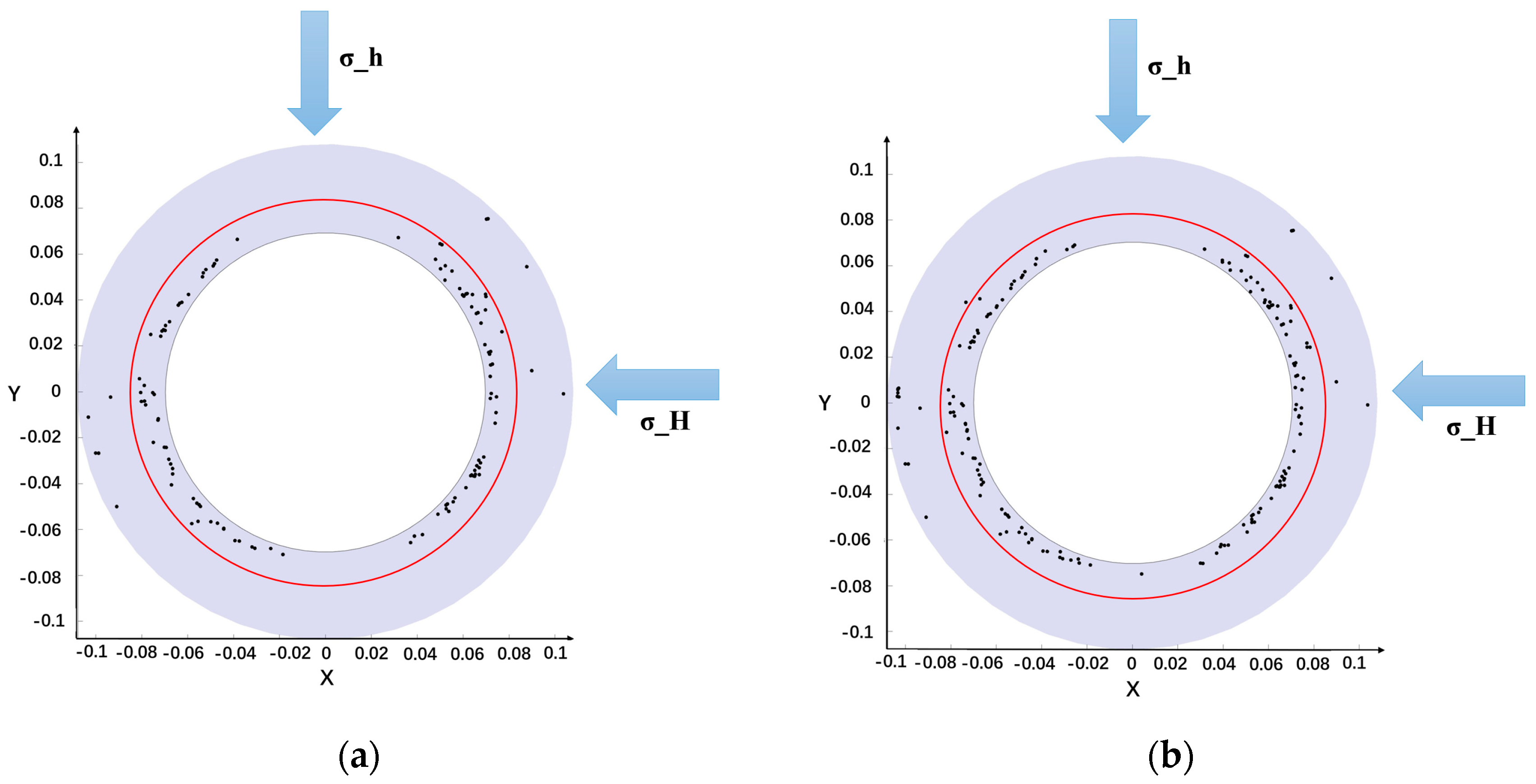

3.2. Analysis of Results

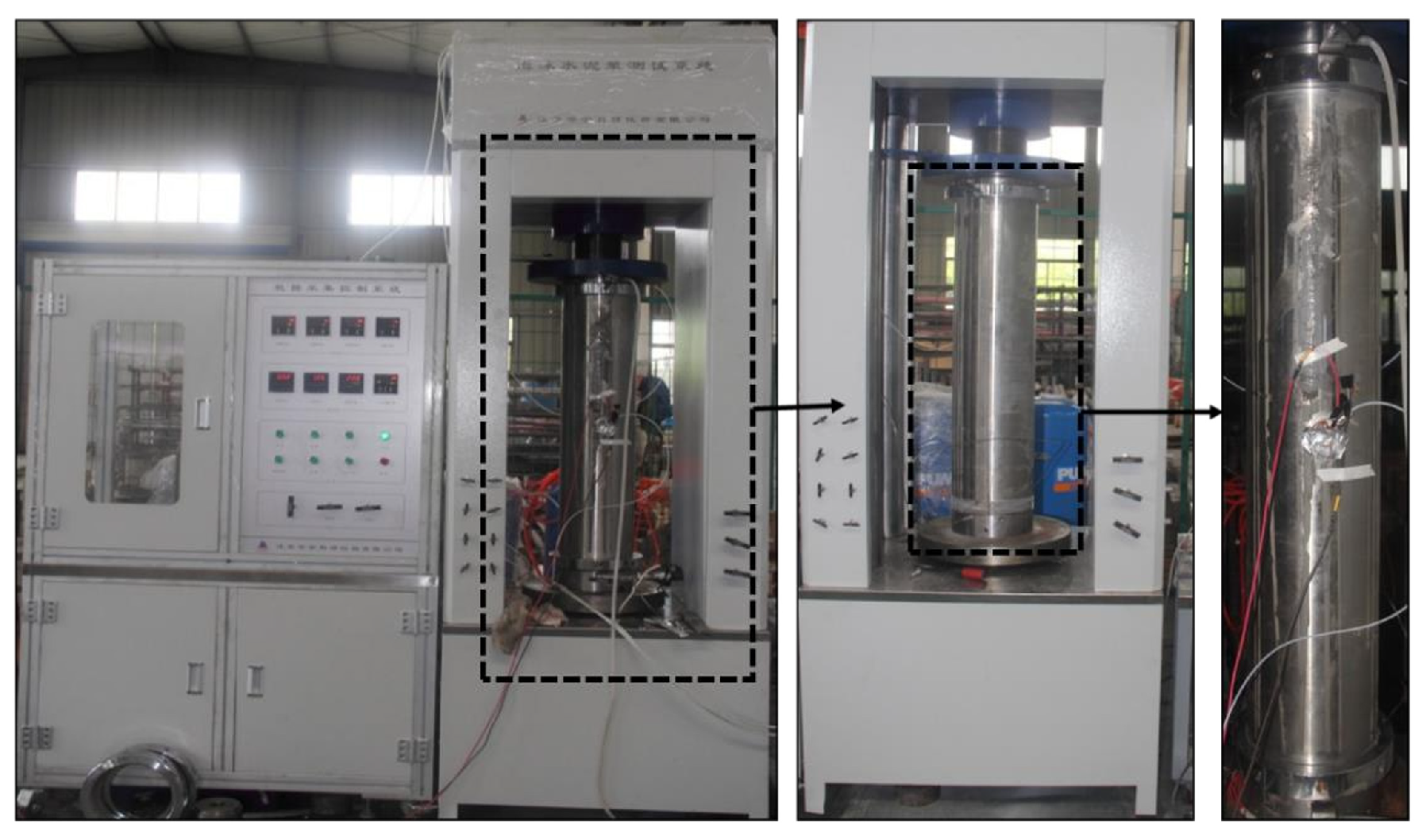

3.3. Model Validation

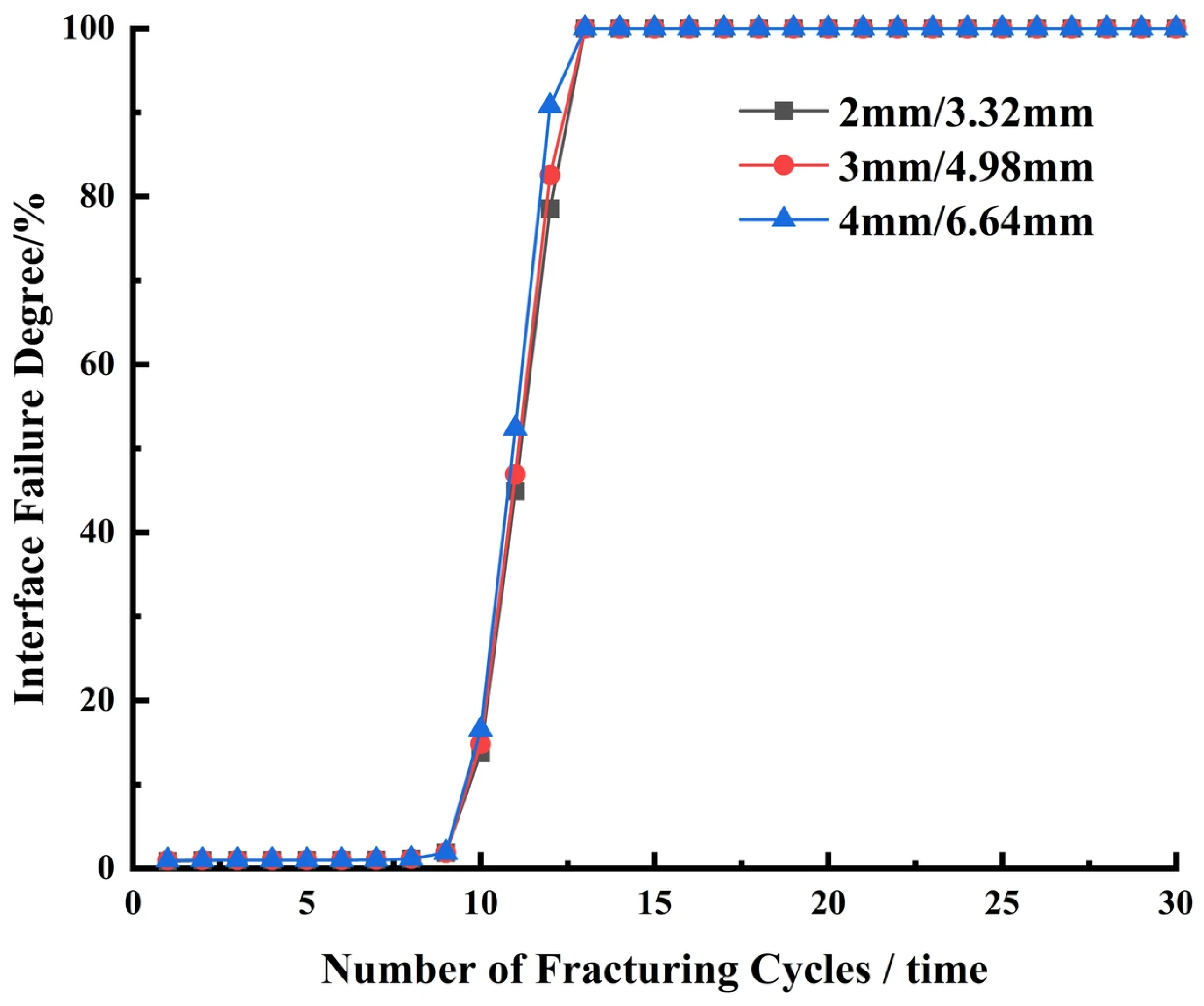

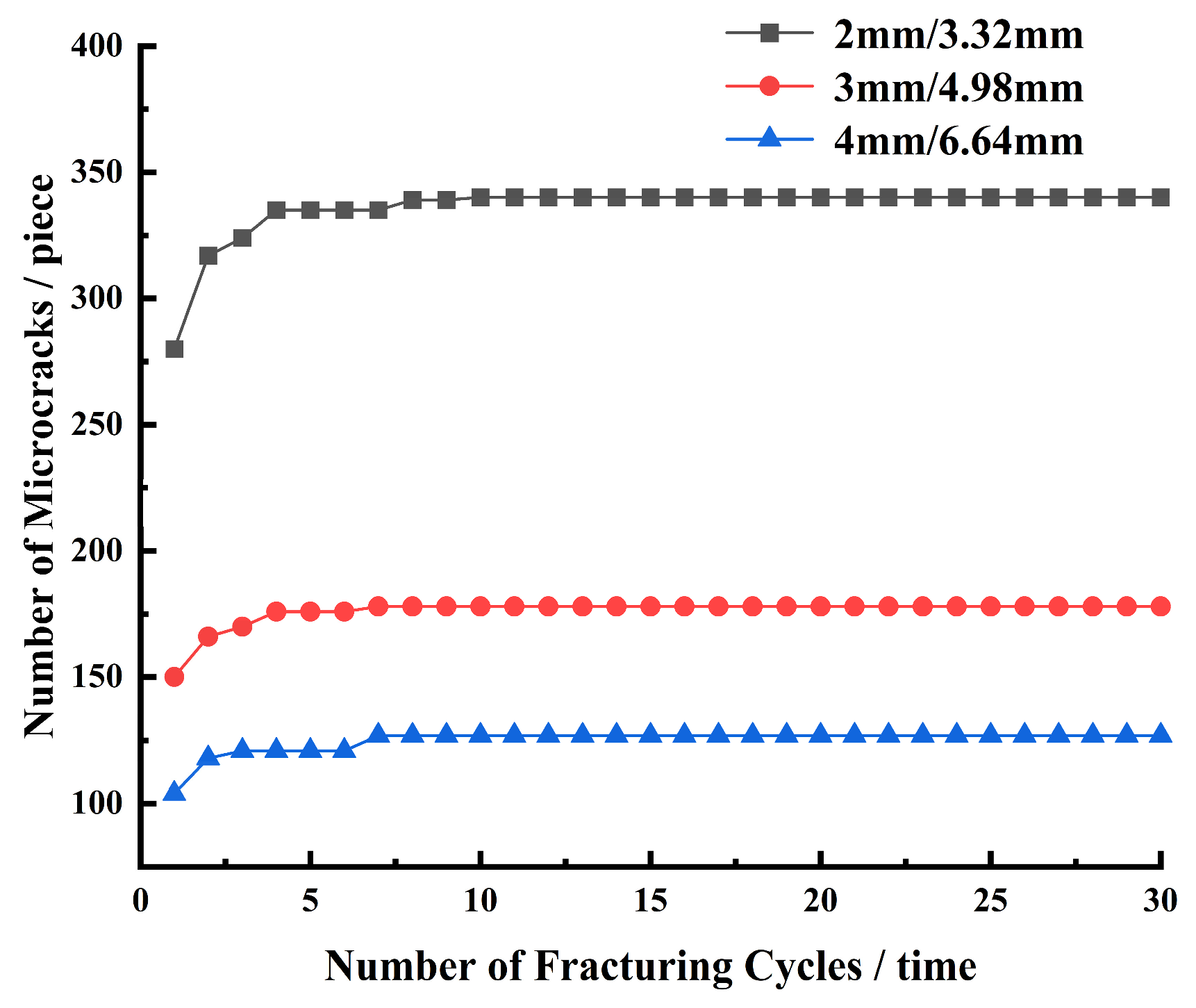

4. Sensitivity Analysis of Cement Sheath Damage Degree

4.1. Influence of Fracturing Location on Cement Sheath Damage Degree

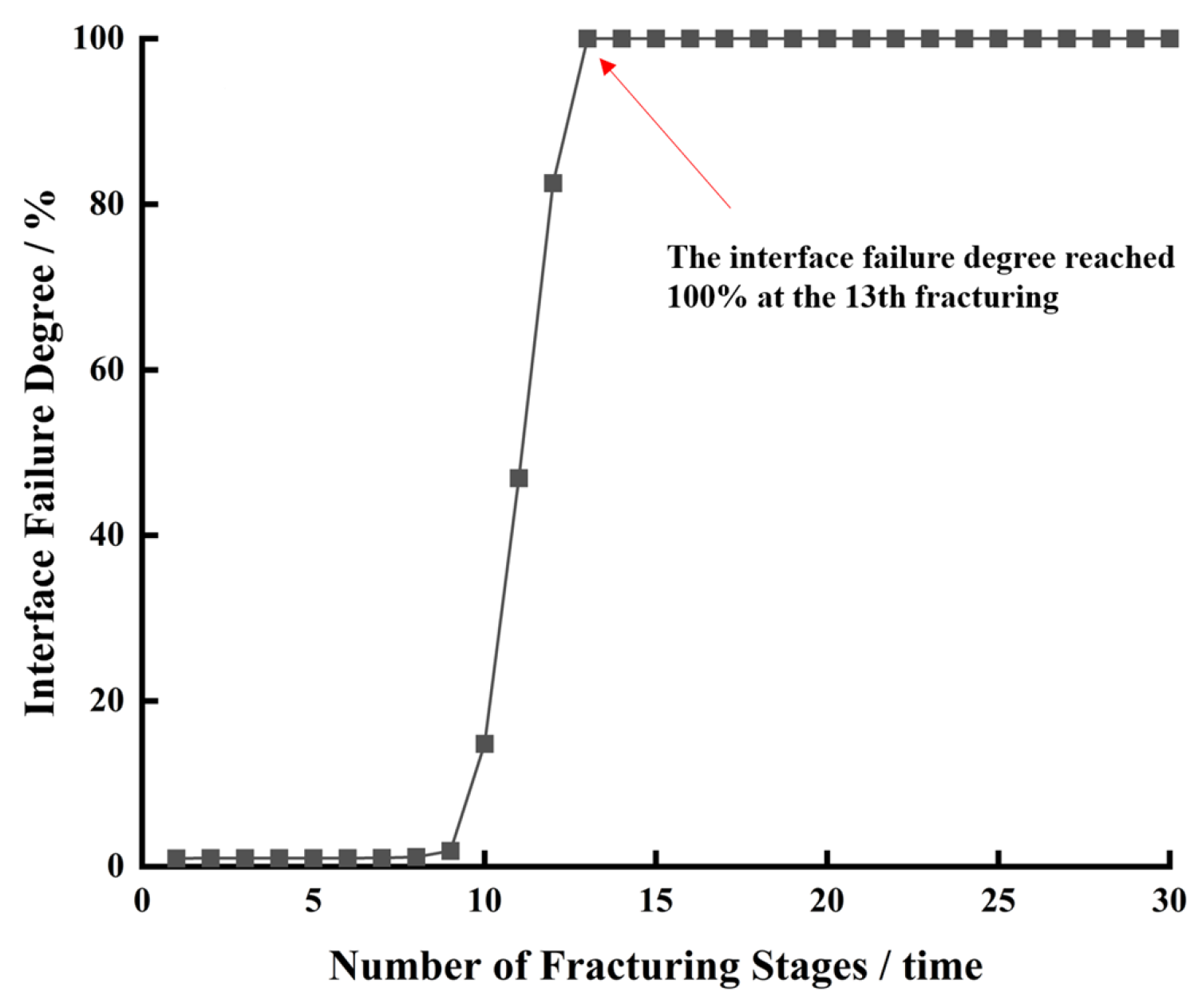

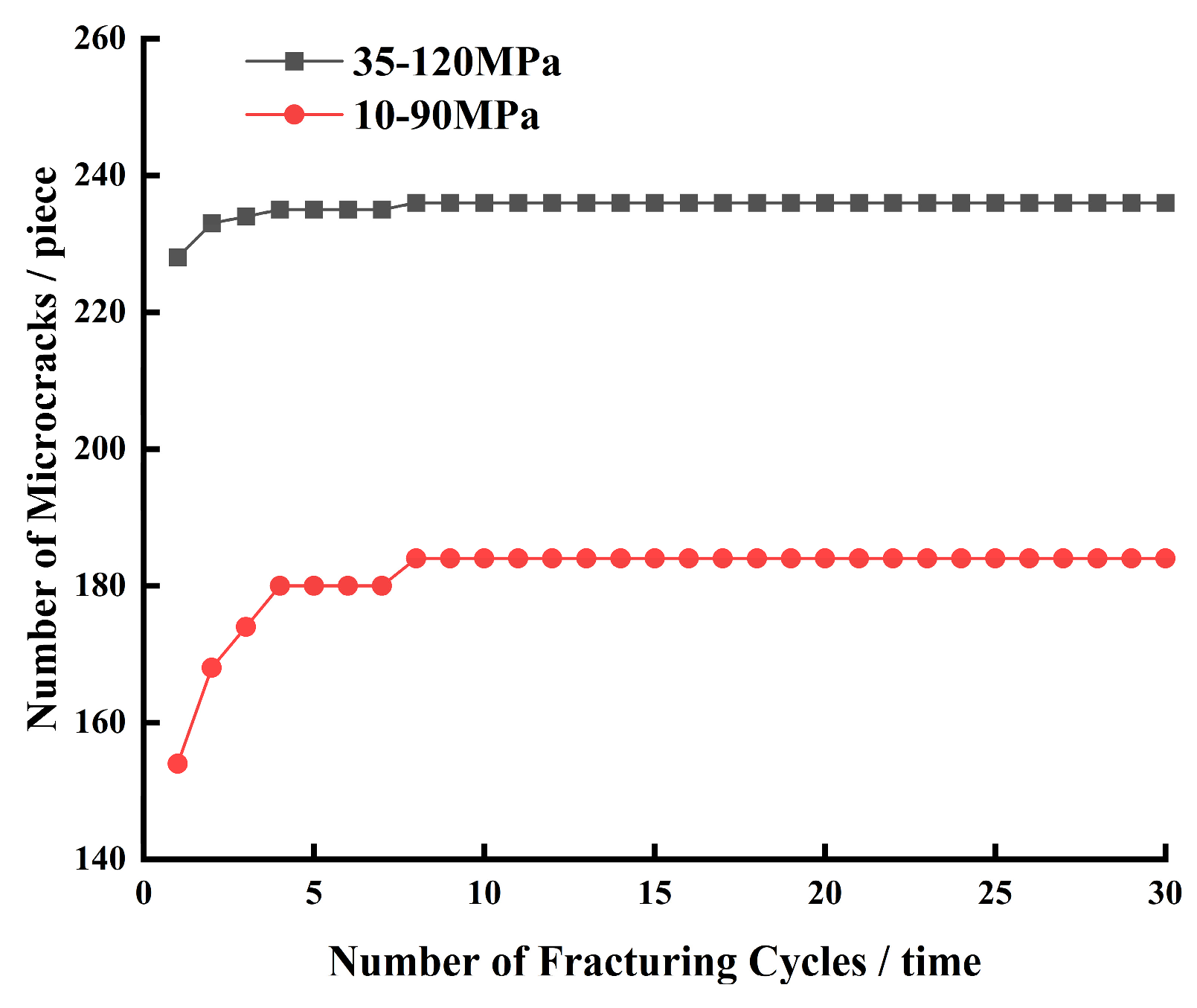

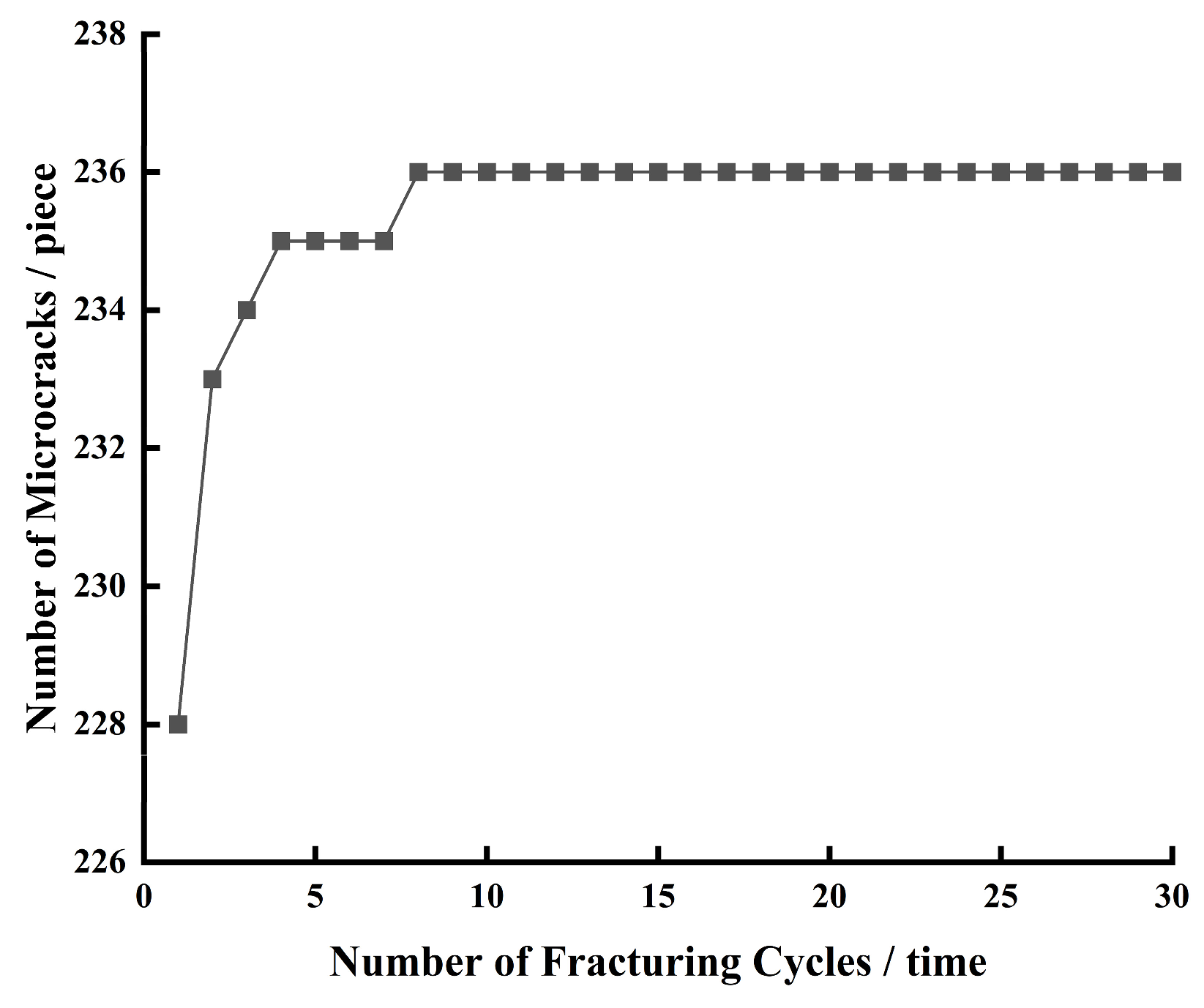

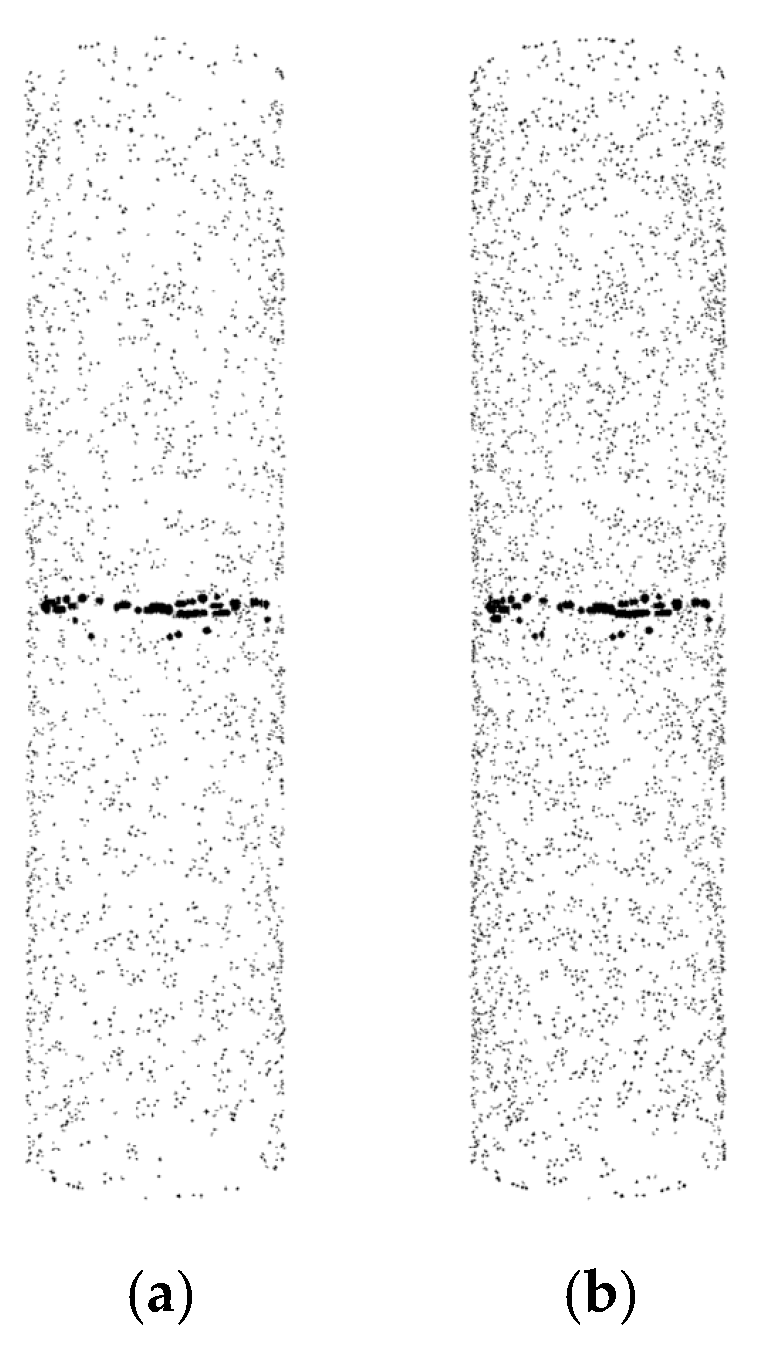

4.2. Influence of Fracturing Stage Number on Cement Sheath Damage Degree

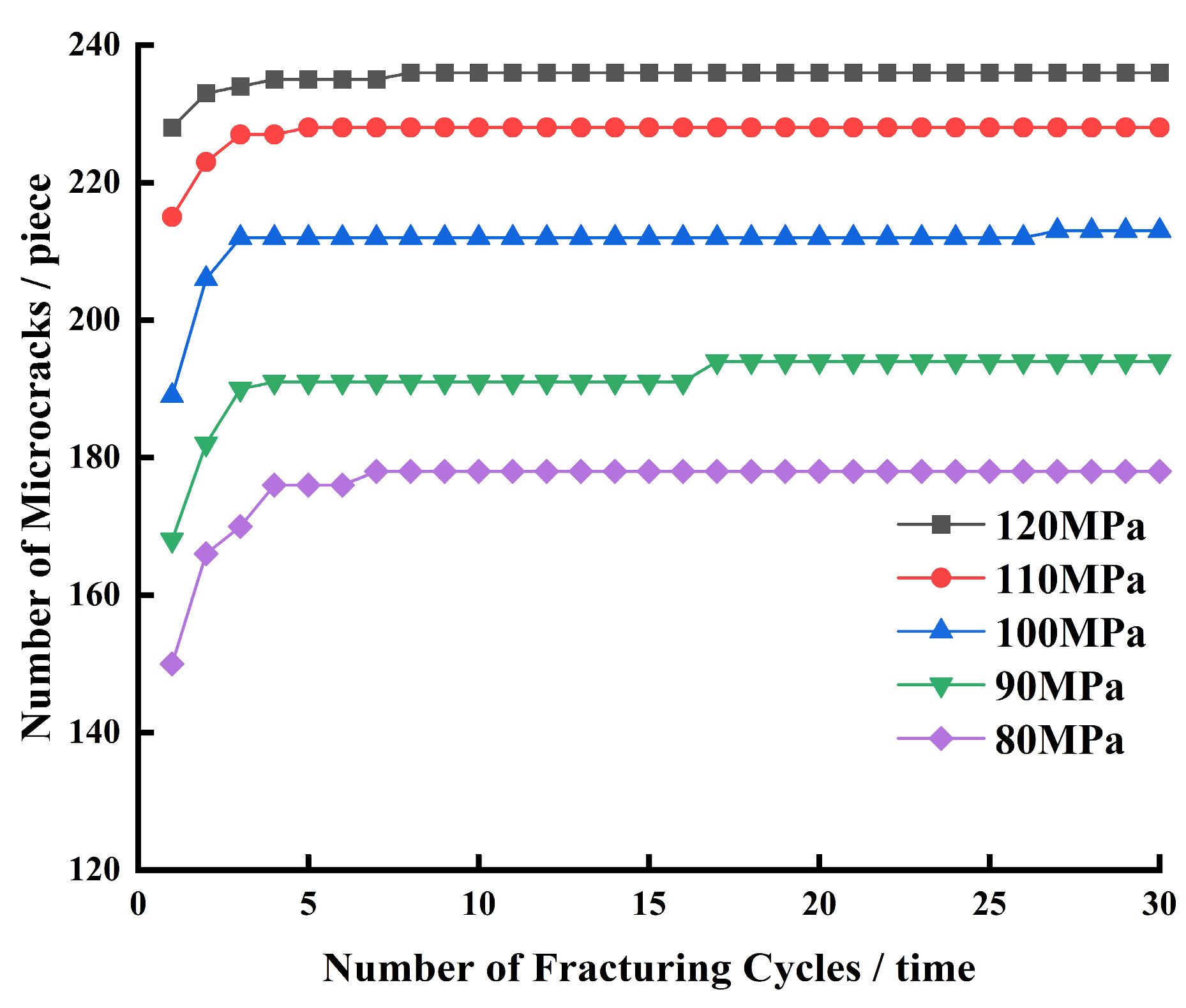

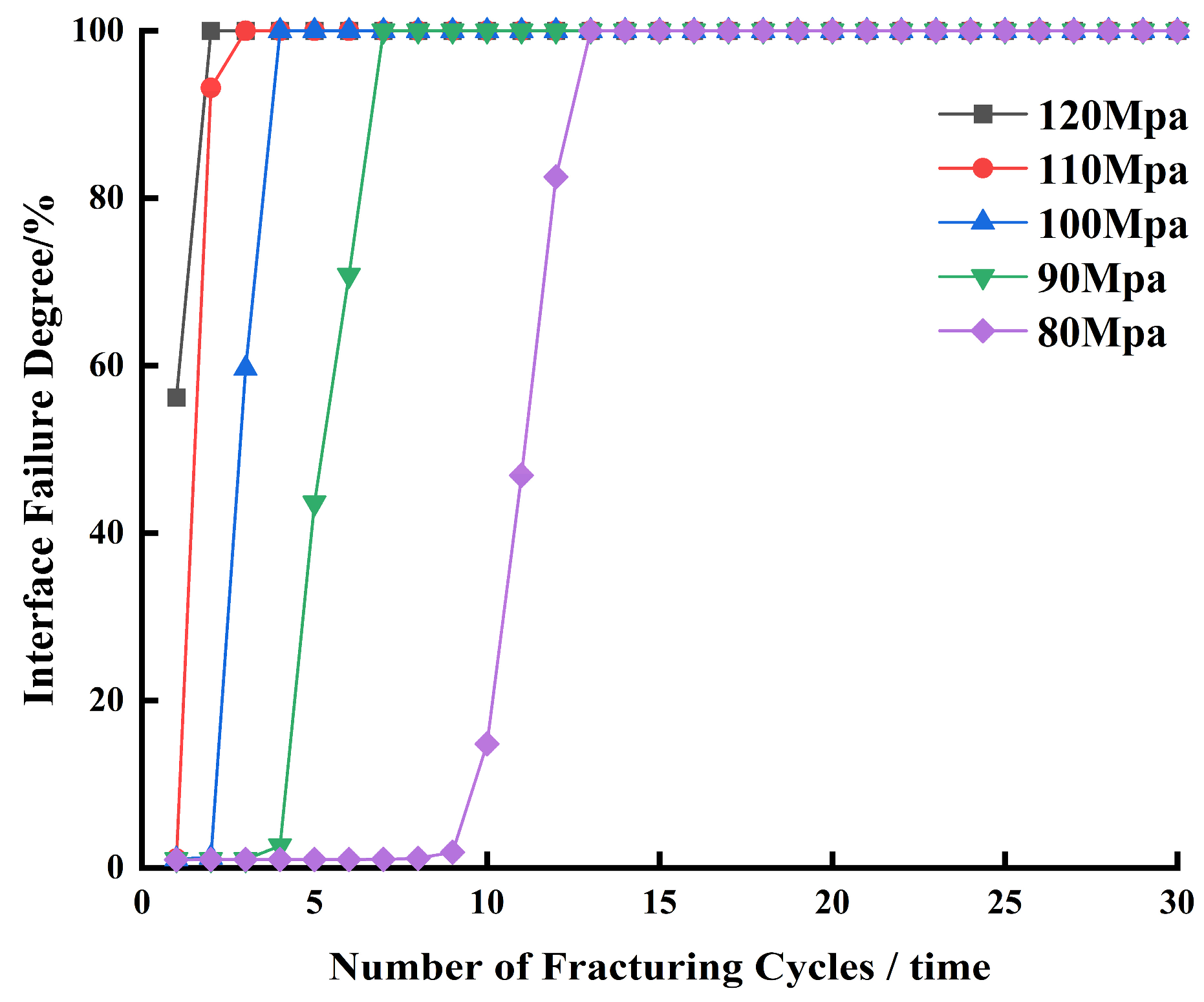

4.3. Influence of Casing Internal Pressure on Cement Sheath Damage Degree

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zou, C.N.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, G.S.; Zhu, R.; Tao, S.Z.; Yuan, X.J.; Hou, L.H.; Dong, D.Z.; Guo, Q.L.; Song, Y.; et al. Theory, Technology and Practice of Unconventional Petroleum Geology. Earth Sci. 2023, 48, 2376–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.Y.; Wu, C.M.; Hu, K.; Chen, Y.W.; Xu, T.L.; Wang, Y.J. Key Technologies and Practice of Shale Oil Cost-Effective Development in Jimsar Sag, Junggar Basin. Xinjiang Oil Gas 2024, 20, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.G.; Chang, L.; Zhou, L.B.; Xi, C.M.; Ouyang, Y. Current Status and Suggestions for Drilling Technology of CNPC Continental Shale Oil Reservoirs. Xinjiang Oil Gas 2024, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Q.; Li, D.Q.; Yuan, J.P.; Qi, F.Z.; Sheng, J.Y.; Guo, M.M. Cement sheath integrity of shale gas wells: A case study from the Sichuan Basin. Nat. Gas Ind. 2017, 37, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibukun, M.; Elyan, E.; Amish, M.; Njuguna, J.; Oluyemi, G.F. A Review of Well Life Cycle Integrity Challenges in the Oil and Gas Industry and Its Implications for Sustained Casing Pressure (SCP). Energies 2024, 17, 5562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, M.; Deng, C.; Li, J.; Gu, M.Z.; Wang, T.Y.; Tian, S.C. Non-Uniform Perforation to Balance Multi-Cluster Fractures Propagation and Parameter Optimization. Xinjiang Oil Gas 2024, 20, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Liu, K.; Tian, S.C. Progresses in shale gas well integrity research. Oil Gas Geol. 2019, 40, 602–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.N.; Lu, B.P.; Liu, Y.S.; Zhou, Y.C.; Liu, X.S.; Liu, W.; Zang, Y.B. Status and research suggestions on the drilling and completion technologies for onshore deep and ultra deep wells in China. Oil Drill. Prod. Technol. 2020, 42, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.H.; Huang, M.; Feng, S. A prediction method of annular pressure in high-pressure gas wells based on the RF and LSTM network models. Nat. Gas Ind. 2024, 44, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.Z.; Sun, Y.D.; Wang, X.L.; Feng, D.F.; Ha, S.M.; Song, W.R. Risk assessment model of sustained casing pressure of gas well based on Bayesian network and its application analysis. Oil Drill. Prod. Technol. 2021, 43, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.J.; Li, J.; Lian, W.; Sun, Z.C.; Zhang, J.C.; Liu, G.H. Study on the sealing integrity of cement sheath under cyclic internal pressure considering temperature effects. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 249, 213761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Guan, Z.C.; Han, L.L.; Liu, Y.H. Coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical analysis of perforated cement sheath integrity during hydraulic fracturing. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 218, 110950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.H.; Zhou, N.T.; Lin, Y.H.; Peng, Y.; Yan, K.; Qin, H.; Xie, P.F.; Li, Z.H. Failure mechanism and control method of cement sheath sealing integrity under alternating thermal-stress coupling in geothermal wells. Renew. Energy 2024, 226, 120448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Liu, X.B.; Li, J.L.; Wang, P.; Han, L.L.; Liu, Y.H. Numerical Simulation of Perforated Cement Sheath Integrity during Staged Fracturing. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2023, 23, 9903–9910. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, K.H.; Zhou, N.T.; Lin, Y.H.; Wu, Y.X.; Chen, J.; Shu, C.; Xie, P.F. Failure mechanism and influencing factors of cement sheath integrity under alternating pressure. Pet. Sci. 2023, 20, 2413–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.J.; Bu, Y.H.; Liu, H.J.; Lu, C.; Guo, S.L.; Xu, H.Z.; Ren, Y.Q. Effects of the mechanical properties of a cement sheath and formation on the sealing integrity of the cement-formation interface in shallow water flow in deep water. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 369, 130496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.M.; Kuru, E.; Jin, Y.J.; Yang, X.X. Numerical investigation of the factors affecting the cement sheath integrity in hydraulically fractured wells. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 215, 110582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Bi, Z.H.; Wang, L.; Guo, Y.T.; Yang, C.H.; Yang, G.G. Shakedown analysis on the integrity of cement sheath under deep and large-scale multi-section hydraulic fracturing. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheibi, S.; Agofack, N.; Sangesland, S. Modified discrete element method (MDEM) as a numerical tool for cement sheath integrity in wells. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 196, 107720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.Q.; Zhao, Z.F.; Wang, X.X. Effect of Horizontal Staged Fracturing on the Integrity of Cement Annulus. J. Southwest Pet. 2021, 43, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Lian, W. Performance Evaluation of the Cement Sheath in Jimsar Shale Oil Wells. Xinjiang Oil Gas 2023, 19, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.D.; Luo, M.; Xiao, P.; Zhou, N.T.; Lin, Y.H. Study on the interface bonding damage behavior of cement sheath under alternating thermal load. Nat. Gas Oil 2024, 42, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, X.Y. Effect of Injection and Production Conditions of Gas Storage Well on Seal-Gas Pressure of Cement Sheath. Contemp. Chem. Ind. 2024, 53, 2560–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.Q.; Tan, Y.M.; Yan, J.T.; Wang, X.Q.; Hou, F.; Zhu, G.P.; Liao, S.Z. Optimization of Cement Slurry System for Gas Storage Based on the Stretching Tensile Strength. Drill. Prod. Technol. 2023, 46, 128–134. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Z.G.; Deng, K.H.; Wu, Y.X.; Lin, Z.W.; Lin, Y.H. Experimental Evaluation on the Cement Sheath Integrity of Unconventional Oil and Gas Well During Large-scale Hydraulic Fracturing. J. Southwest Pet. 2023, 45, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, D.M.; Emadi, H.; Hussain, A.; Thiyagarajan, S.R.; Ispas, I.; Watson, M. Experimental investigation of the impact of short-term hydrogen exposure on cement sheath’s mechanical and sealing integrity. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 251, 213885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.T.; Wu, L.W.; Yuan, J.J.; Xiao, F.P.; Deng, K.H.; Lin, Y.H. Feasibility evaluation of cement sheath sealing within large-size casing structures in gas and hydrogen storage wells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 115, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.H.; Deng, K.H.; Yi, H.; Zeng, D.Z.; Tang, L.; Wei, Q. Integrity tests of cement sheath for shale gas wells under strong alternating thermal loads. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2020, 7, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathija, A.P.; Boyd, P.; Martinez, R. Cement sheath integrity at simulated reservoir conditions of pressure, temperature, and wellbore configuration in a laboratory setup. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 232, 212446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.N. Particle Flow Code (PFC5.0) Numerical Simulation Technology and Its Applications. Rock Soil Mech. 2018, 39, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, K.; Chen, L.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Zhang, Z.Z. Discrete Element Fluid-Solid Coupling Simulation of Fracture Mechanisms in Deep Fluid-Bearing Rocks. J. Oil Gas Technol. 2025, 47, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, Y.T.; Wang, L.; Hou, Z.K.; Xu, F. An experimental study on mechanical anisotropy of shale reservoirs at different depths. Rock Soil Mech. 2017, 38, 2496–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

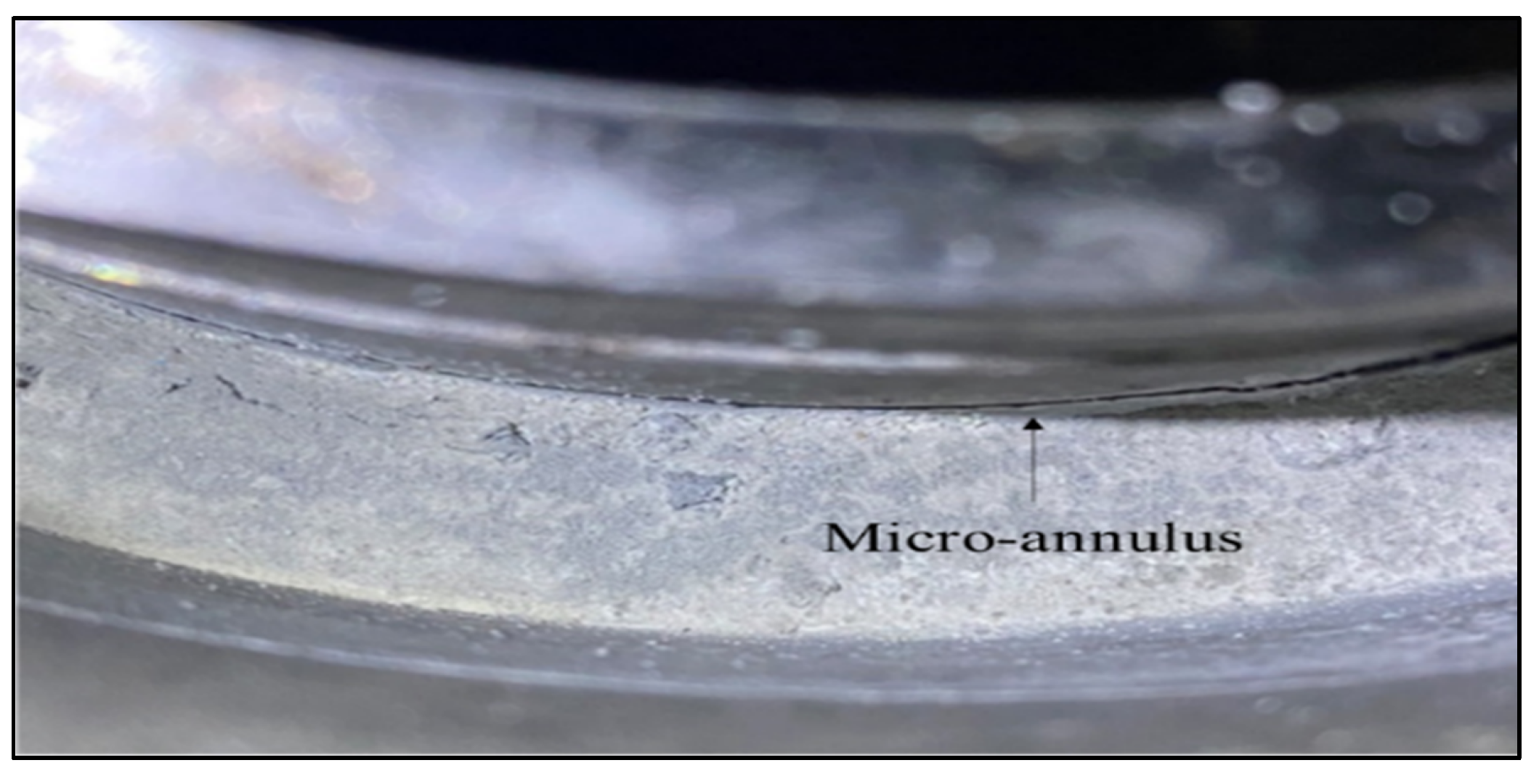

- Xi, Y.; Li, F.Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, M.J.; Xia, M.L.; Zeng, X.M.; Zhong, W.L. Study on Prevention of Micro—Annulus in Cement Sheath by Prestressed Cementing Method. Spec. Oil Gas Reserv. 2021, 28, 144–150.1006–6535. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.M.; Ling, D.S.; Huang, B.; Chen, Y.M. Determination of shear wave velocity in granular materials by shear vibration within discrete element simulation. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2011, 33, 1462–1468. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, W.; Li, J.; Xu, D.R.; Lu, Z.Y.; Ren, K.; Wang, X.G.; Chen, S. Sealing failure mechanism and control method for cement sheath in HPHT gas wells. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 3593–3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experiment Names | Temperature | Loading Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Cement stone uniaxial compression test | 25 °C | 2 kN/min |

| Cement stone triaxial compression test (10 MPa) | 70 °C | 2 kN/min |

| Cement stone triaxial compression test (15 MPa) | 70 °C | 2 kN/min |

| Cement stone Brazilian splitting test | 25 °C | 2 kN/min |

| Casing–cement interface cementation test | 25 °C | 2 kN/min |

| Cement stone cyclic loading–unloading test (15 MPa) | 70 °C | 2 kN/min |

| Material Name | Elastic Modulus/GPa | Compressive Strength/MPa | Tensile Strength/MPa | Poisson’s Ratio/Dimensionless |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casing | 206 | 758 | 860 | 0.30 |

| Casing–Cement Bonding Interface | 0.34 | |||

| Cement Stone | 7.036 | 38.5 | 2.12 | 0.138 |

| Shale | 34 | 118 | 6 | 0.25 |

| Material Name | /GPa | /Dimless | /MPa | /MPa | k/Dimless | /Dimless | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casing | 54 | 54 | 200 | 200 | 45 | 1.5 | 0.5 |

| Casing–Cement Sheath Interface | 1.9 | 1.9 | 3 | 3 | 40 | 1.3 | 0.5 |

| Cement Sheath | 1.9 | 1.9 | 18 | 18 | 40 | 1.3 | 0.5 |

| Cement Sheath–Shale | 1.9 | 1.9 | 18 | 18 | 40 | 1.3 | 0.5 |

| Shale | 11 | 11 | 200 | 200 | 45 | 1.5 | 0.5 |

| Mechanical Parameters | Simulated Value | Experimental Value | Error Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cement Stone Elastic Modulus/GPa | 7.52 | 7.04 | 6.87% |

| Cement Stone Compressive Strength/MPa | 41.3 | 38.5 | 7.27% |

| Cement Stone Tensile Strength/MPa | 2.25 | 2.12 | 6.12% |

| Cement Stone Peak Stress (Confining Pressure 10 MPa)/MPa | 86.43 | 85.54 | 1.04% |

| Cement Stone Peak Stress (Confining Pressure 15 MPa)/MPa | 99.93 | 100.04 | 0.11% |

| Casing–Cement Bonding Interface Tensile Strength/MPa | 0.39 | 0.36 | 8.3% |

| Cement Stone Residual Strain under 50 MPa Cyclic Loading (Confining Pressure 10 MPa)/% | 0.393 | 0.367 | 7.08% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Xie, S.; Zhang, H.; Guan, Z.; Zhou, S.; Mu, J.; Sun, W.; Lian, W. Damage Mechanism and Sensitivity Analysis of Cement Sheath Integrity in Shale Oil Wells During Multi-Stage Fracturing Based on the Discrete Element Method. Eng 2026, 7, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010048

Wang X, Xie S, Zhang H, Guan Z, Zhou S, Mu J, Sun W, Lian W. Damage Mechanism and Sensitivity Analysis of Cement Sheath Integrity in Shale Oil Wells During Multi-Stage Fracturing Based on the Discrete Element Method. Eng. 2026; 7(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010048

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xuegang, Shiyuan Xie, Hao Zhang, Zhigang Guan, Shengdong Zhou, Jiaxing Mu, Weiguo Sun, and Wei Lian. 2026. "Damage Mechanism and Sensitivity Analysis of Cement Sheath Integrity in Shale Oil Wells During Multi-Stage Fracturing Based on the Discrete Element Method" Eng 7, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010048

APA StyleWang, X., Xie, S., Zhang, H., Guan, Z., Zhou, S., Mu, J., Sun, W., & Lian, W. (2026). Damage Mechanism and Sensitivity Analysis of Cement Sheath Integrity in Shale Oil Wells During Multi-Stage Fracturing Based on the Discrete Element Method. Eng, 7(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010048