Collaborative Obstacle Avoidance for UAV Swarms Based on Improved Artificial Potential Field Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Improved APF with Introduction of the Virtual Target Position Function and Additional Virtual Target Points

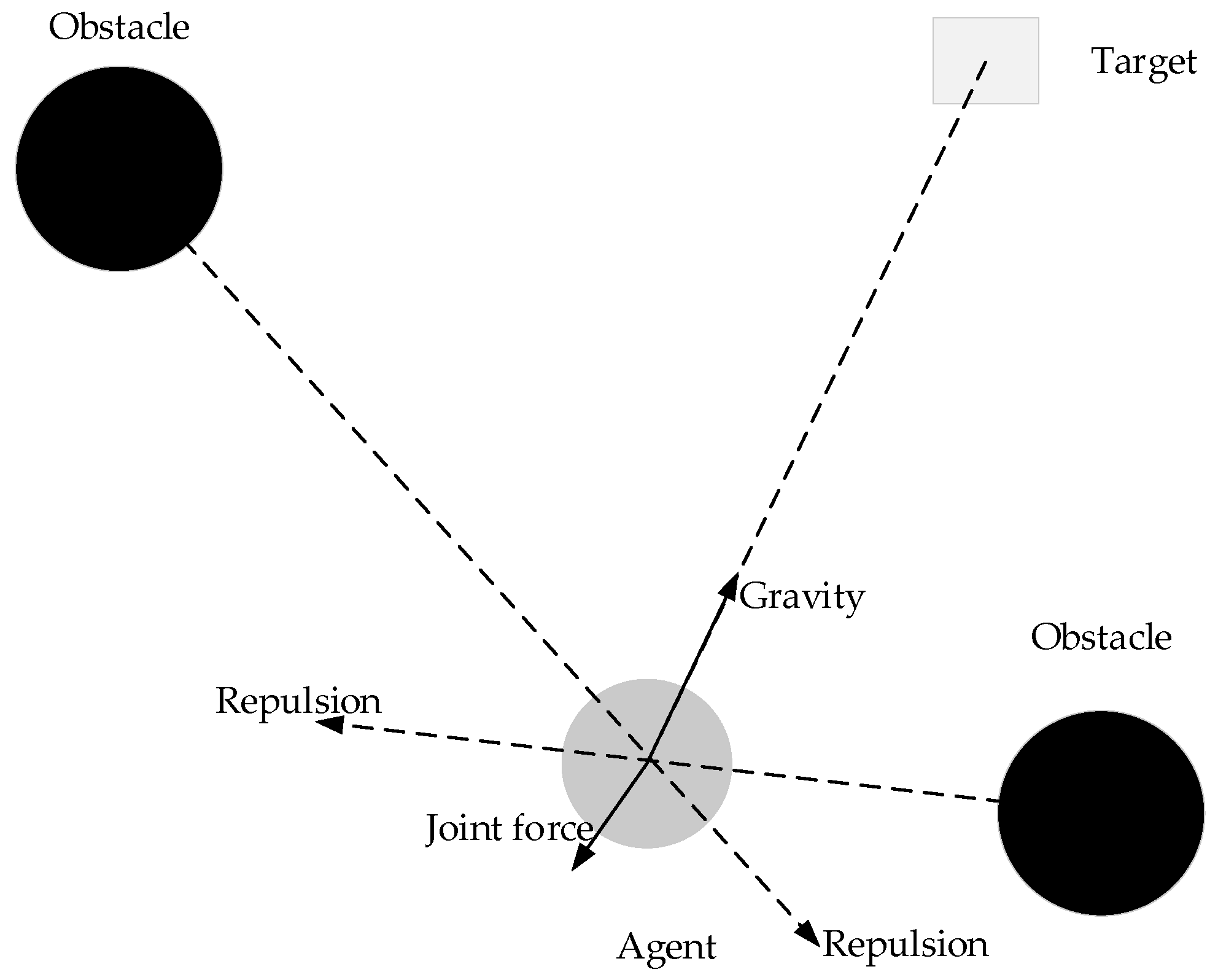

2.1. Traditional APF Theory

2.2. Target Position Function

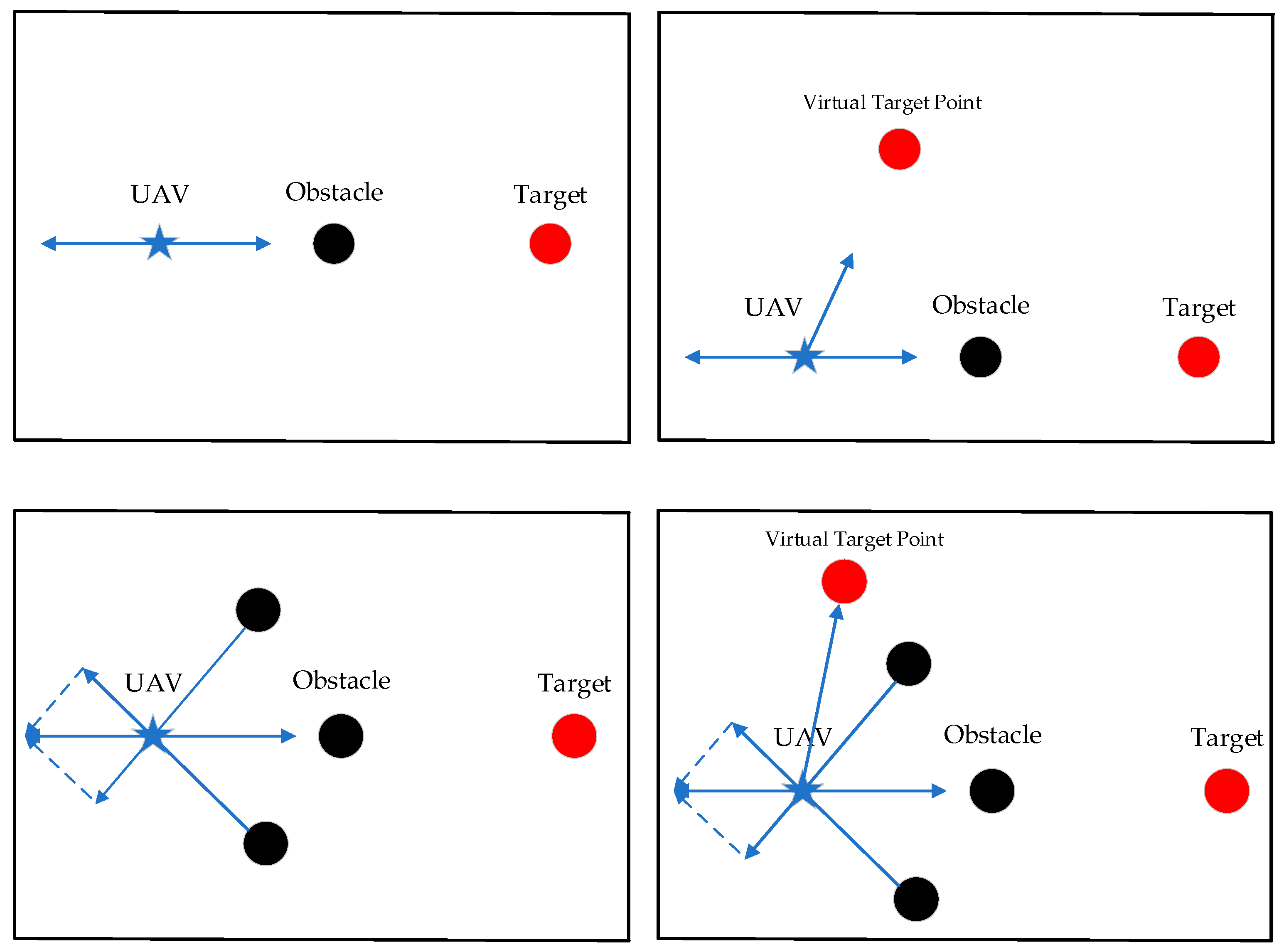

2.3. Virtual Target Point

2.4. Stability and Convergence Analysis of the Improved APF Algorithm

2.4.1. Definition of Lyapunov Candidate Function

2.4.2. Key Properties of the Lyapunov Function

2.4.3. Stability and Convergence Conclusion

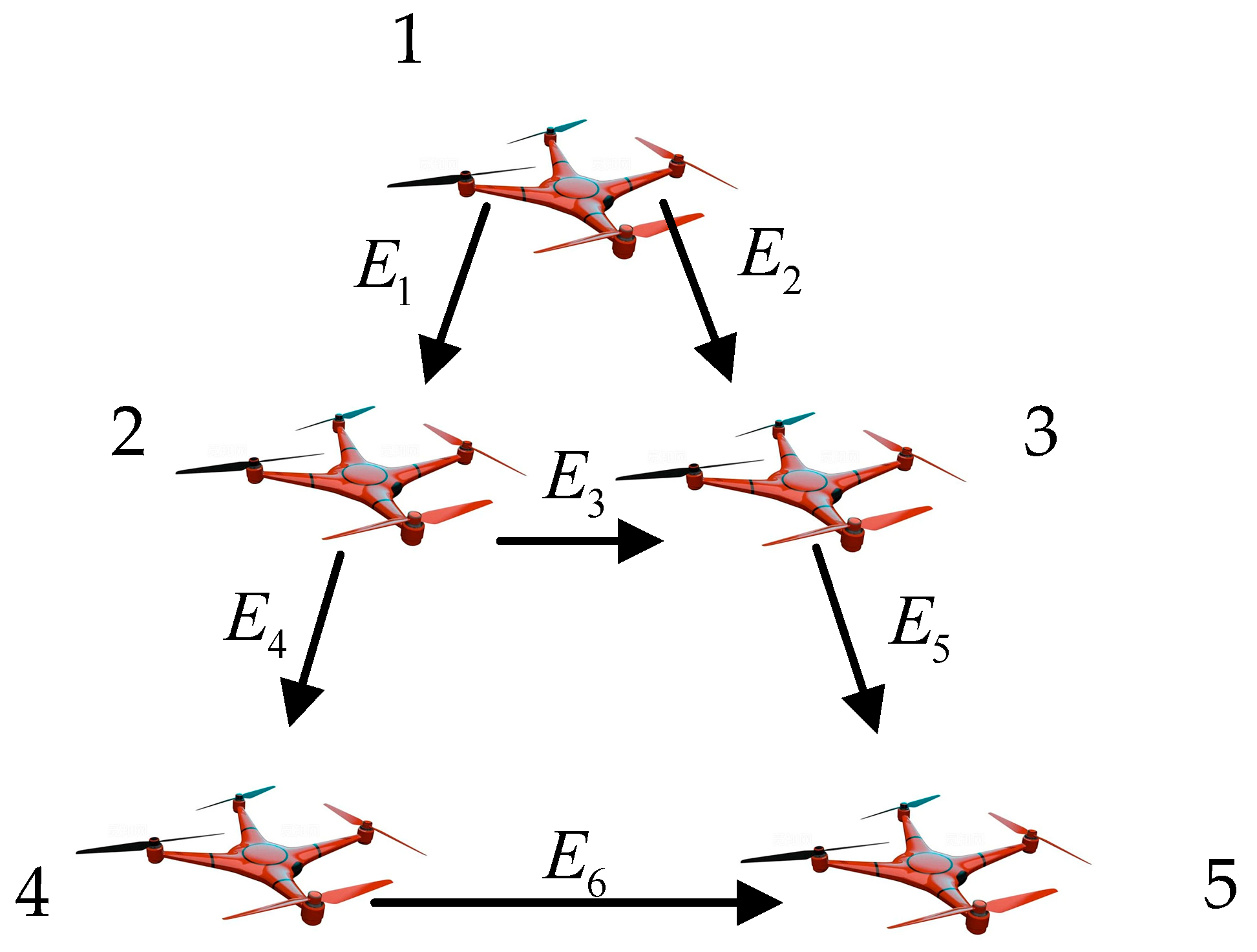

3. Application Design of Improved APF in UAV Formation

3.1. Repulsive Force Between Adjacent UAVs

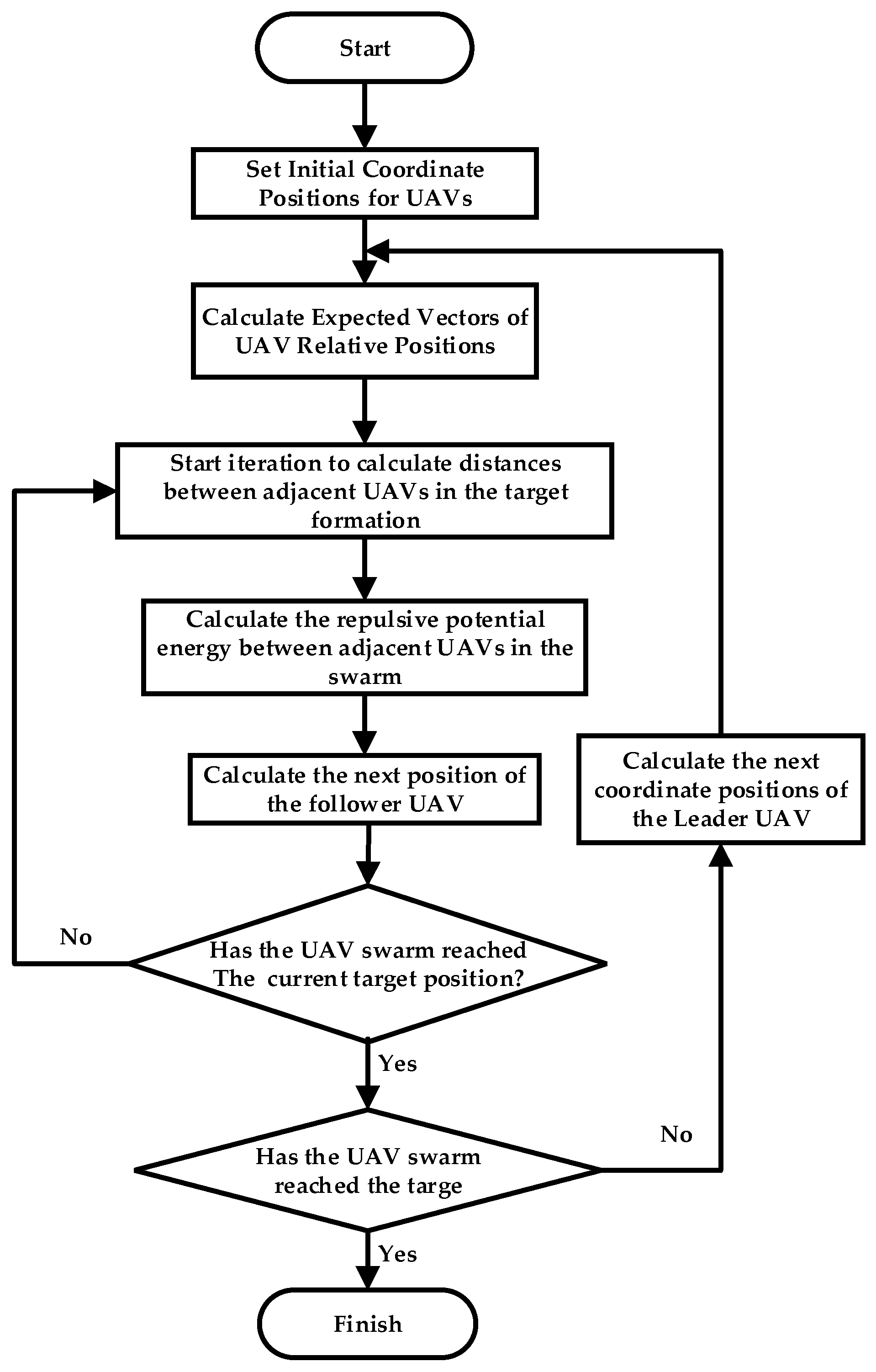

3.2. Algorithm Flow

- (1)

- Set the relative positions of all members in the formation.

- (2)

- Calculate each UAV’s vector in the potential field environment.

- (3)

- Initialize data storage to record the UAV coordinates during flight.

- (4)

- Initialize a distance array between adjacent UAVs to store the distances between each UAV and its two nearest neighbors.

- (5)

- Iteratively compute the straight-line distances between UAVs in the formation.

- (6)

- Calculate the repulsive potential gradient between a single UAV and its neighbors, storing the results in the repulsive potential gradient array.

- (7)

- Determine whether the target position is reached by computing the difference between the UAV’s current position and its ideal position. If not, adjust the step size of the leader.

- (8)

- Compute the next movement of each UAV based on the resultant force acting on it.

- (9)

- Repeat steps (2)–(8) until the formation reaches the target position.

- (1)

- Formation shaping (initial UAV arrangement),

- (2)

- Formation maintenance (ensuring structure stability during movement),

- (3)

- Collision avoidance between robots during formation assembly.

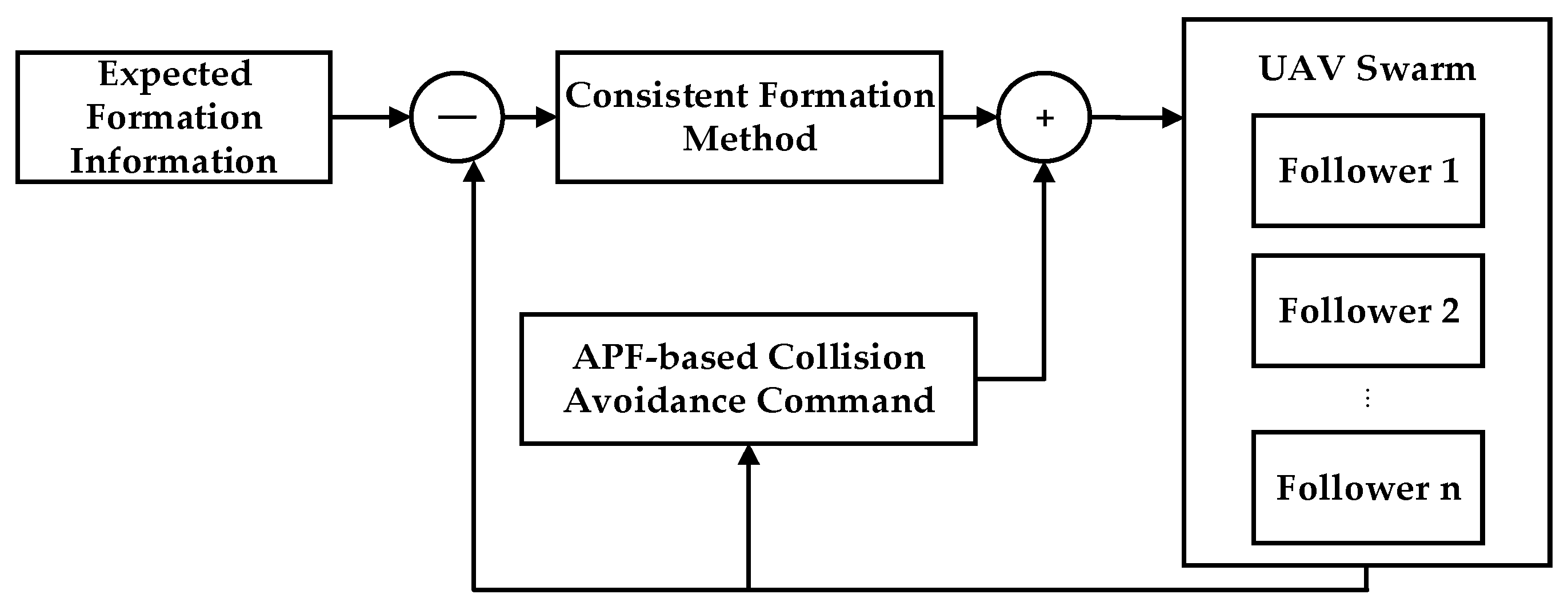

3.3. Controller Design

3.4. Convergence Analysis of the Leader–Follower Control Strategy

3.4.1. Relative Position Error Model

3.4.2. Convergence Proof Based on Lyapunov Theory

3.4.3. Robustness and Convergence Rate

4. Simulation and Result Analysis

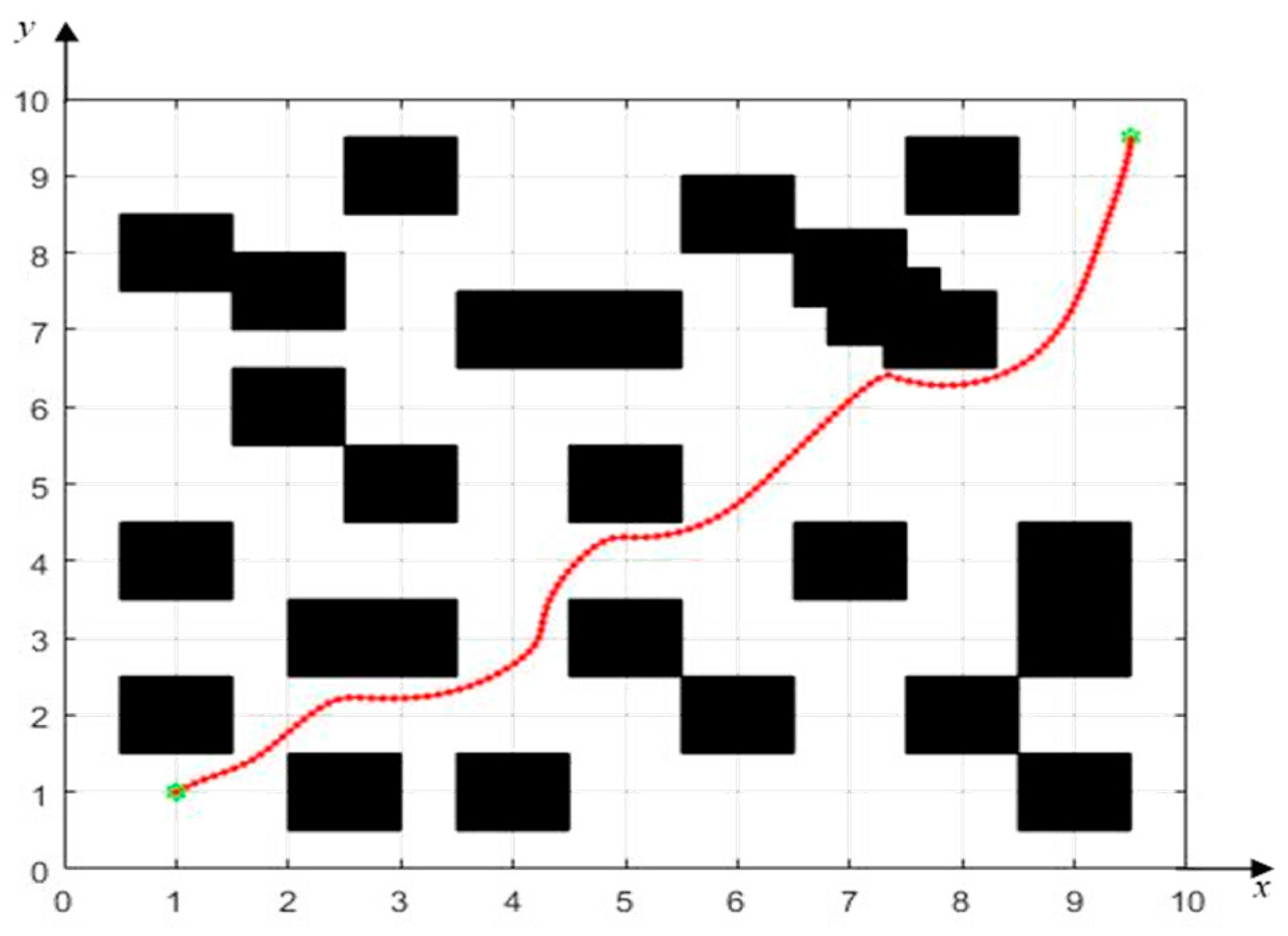

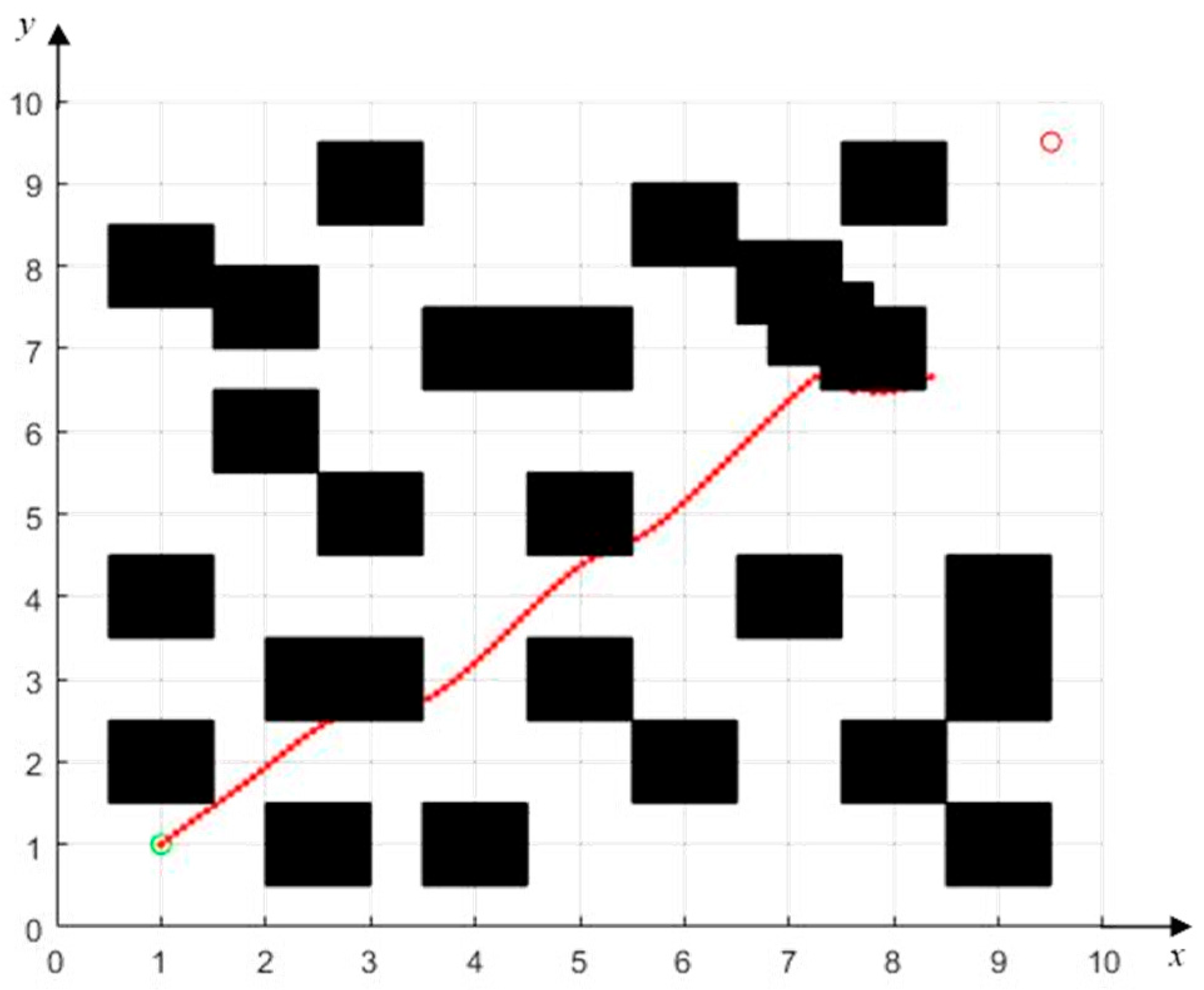

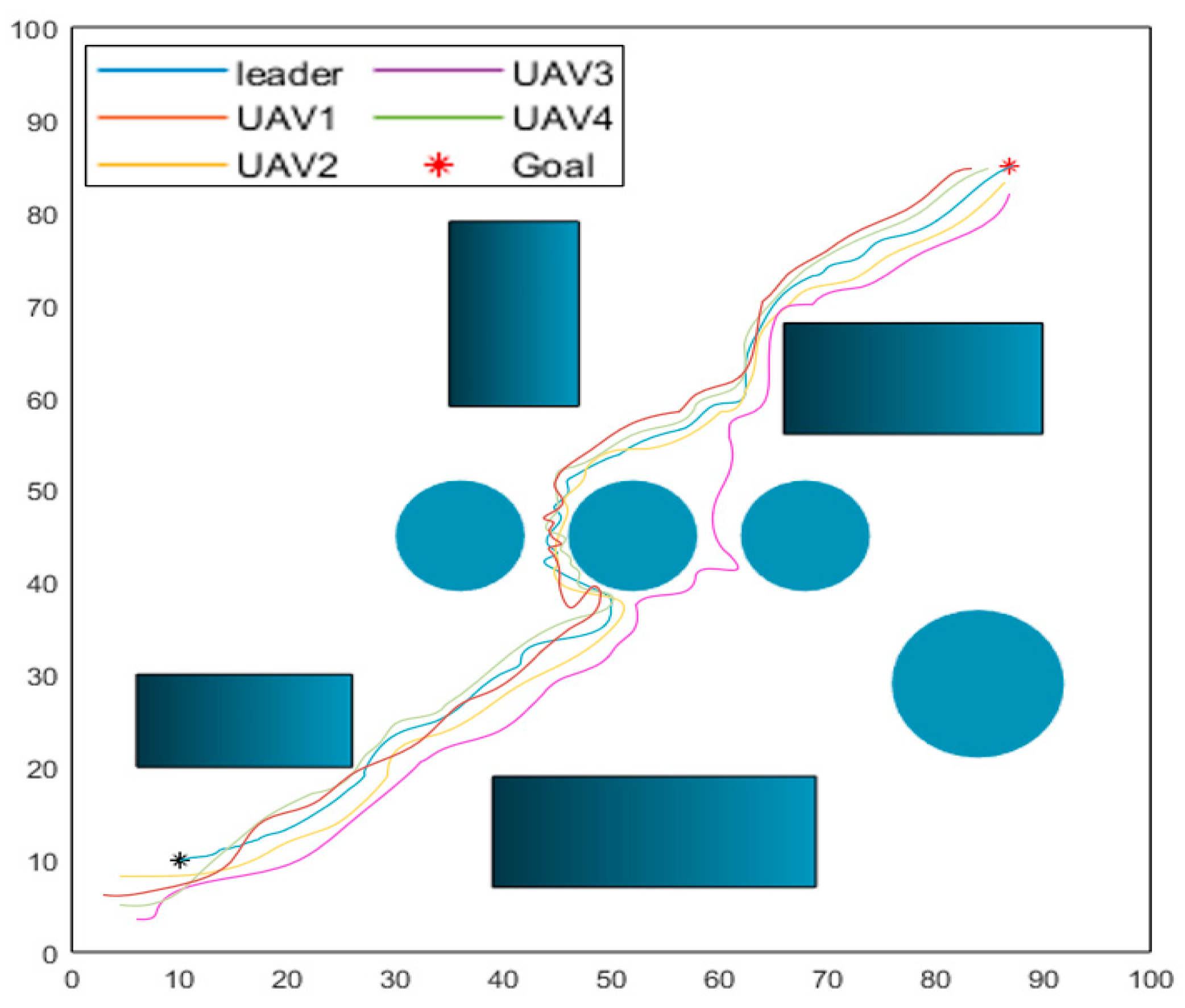

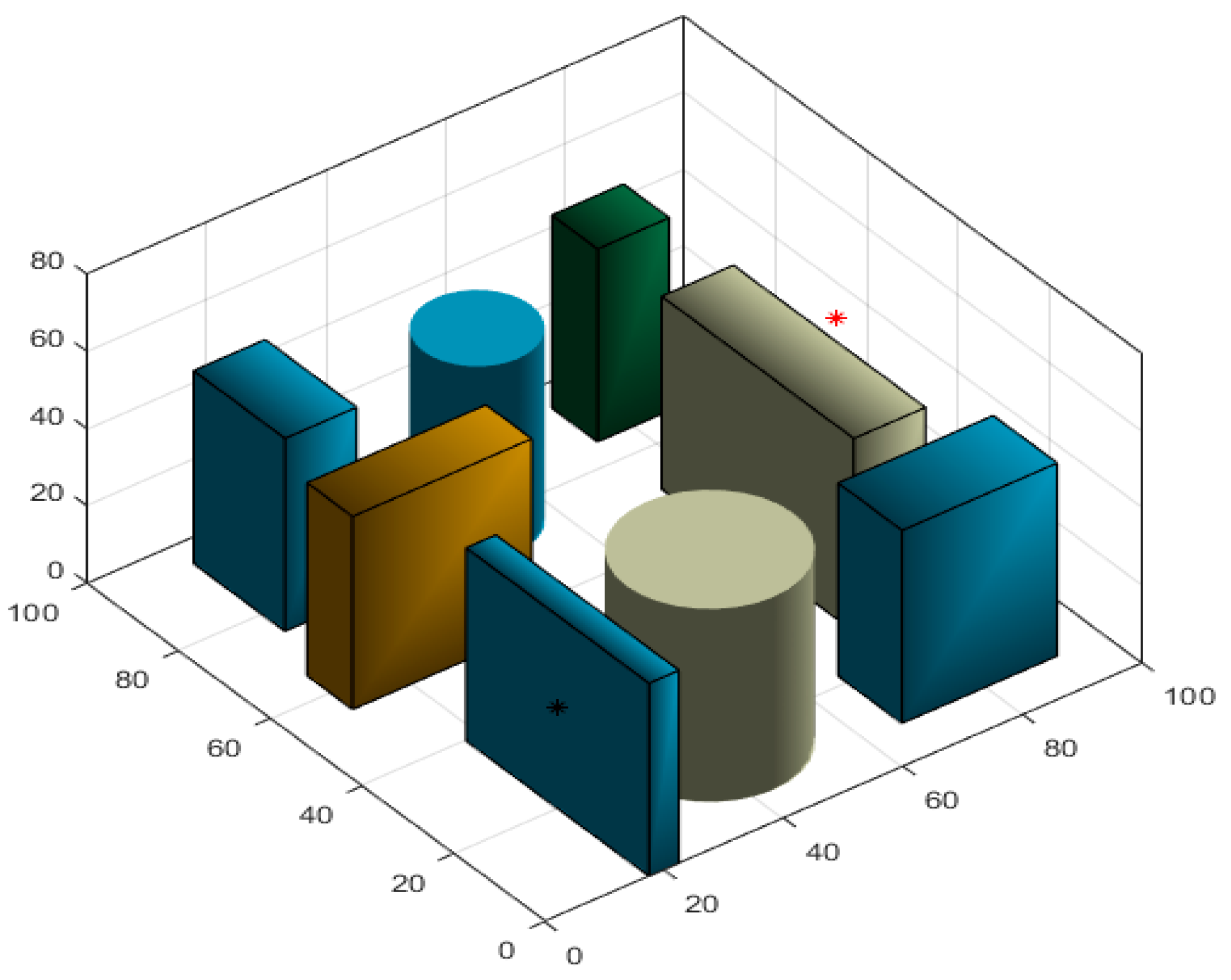

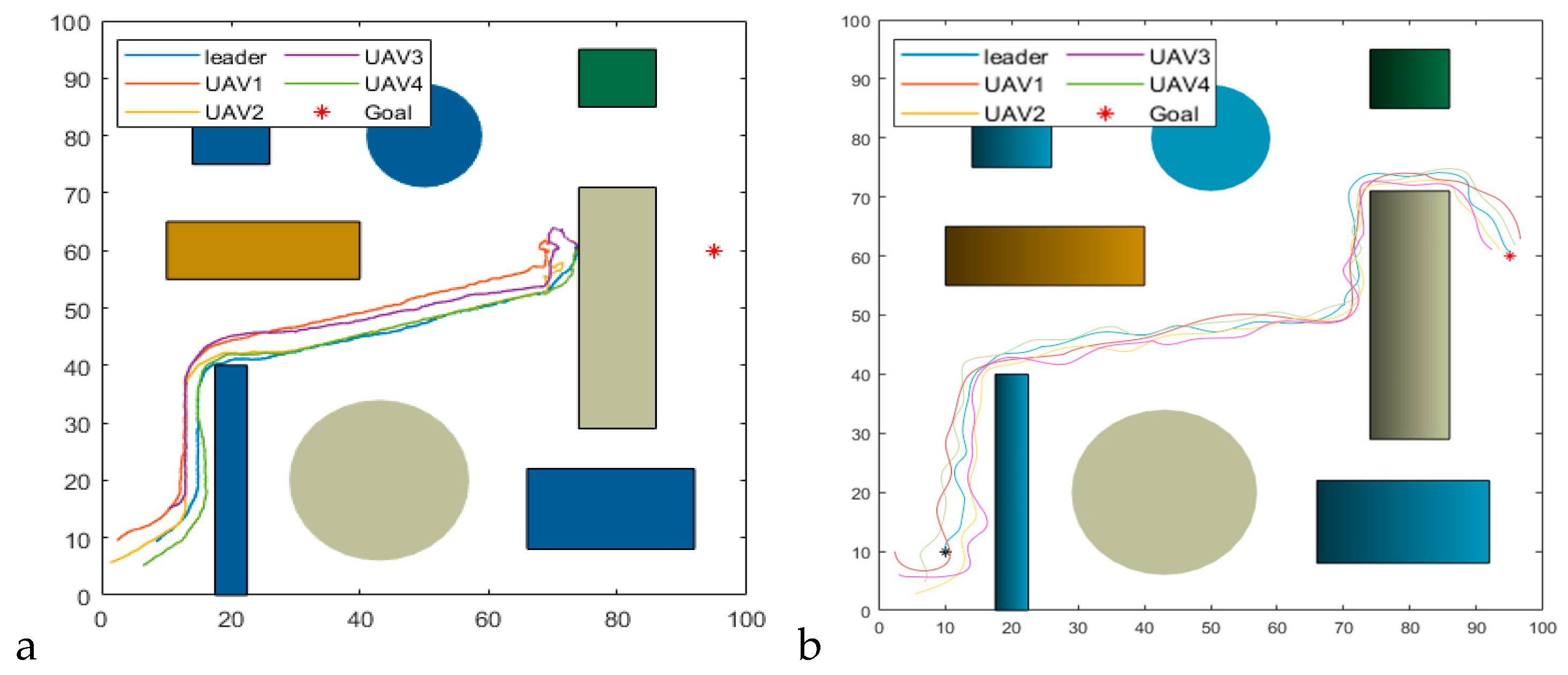

4.1. UAV Swarm Formation

- (1)

- Obstacle avoidance through densely aligned obstacles.

- (2)

- Obstacle avoidance with the target located behind obstacles.

4.2. Simulation Result Analysis

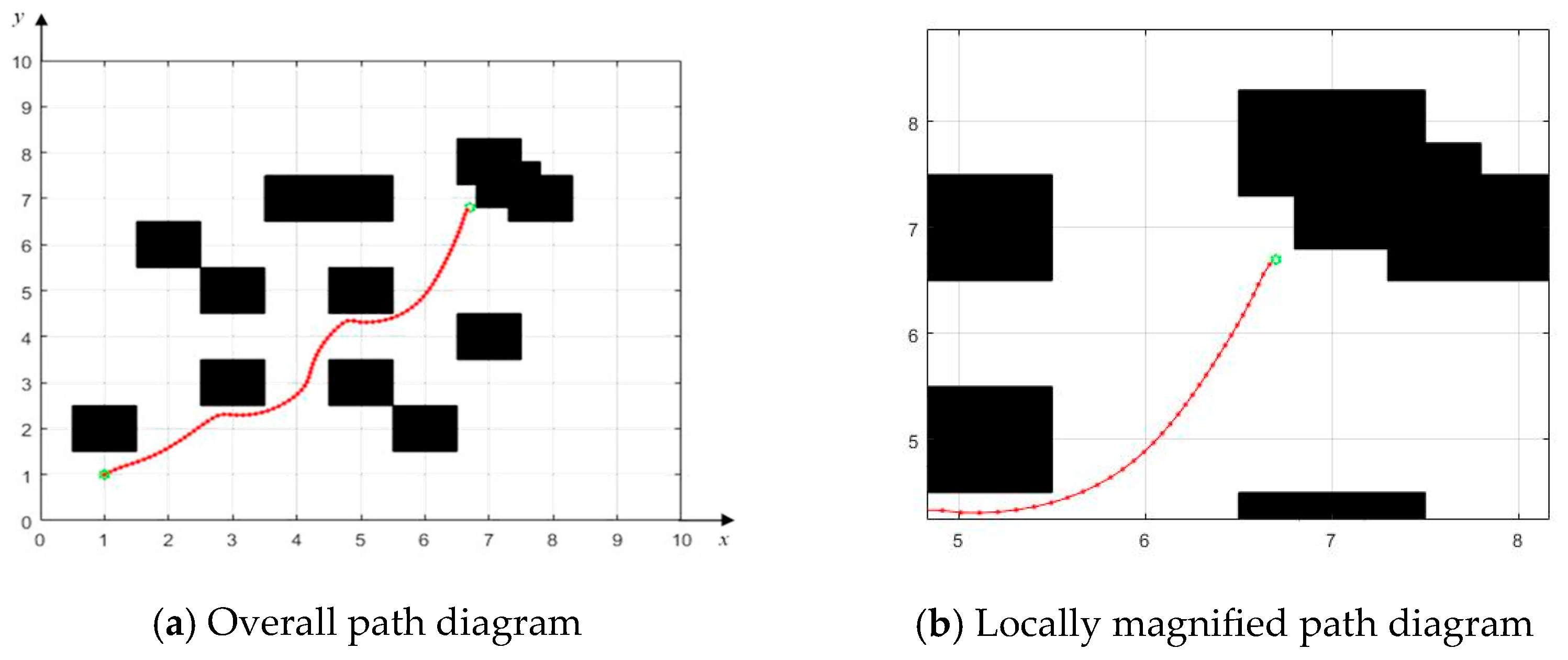

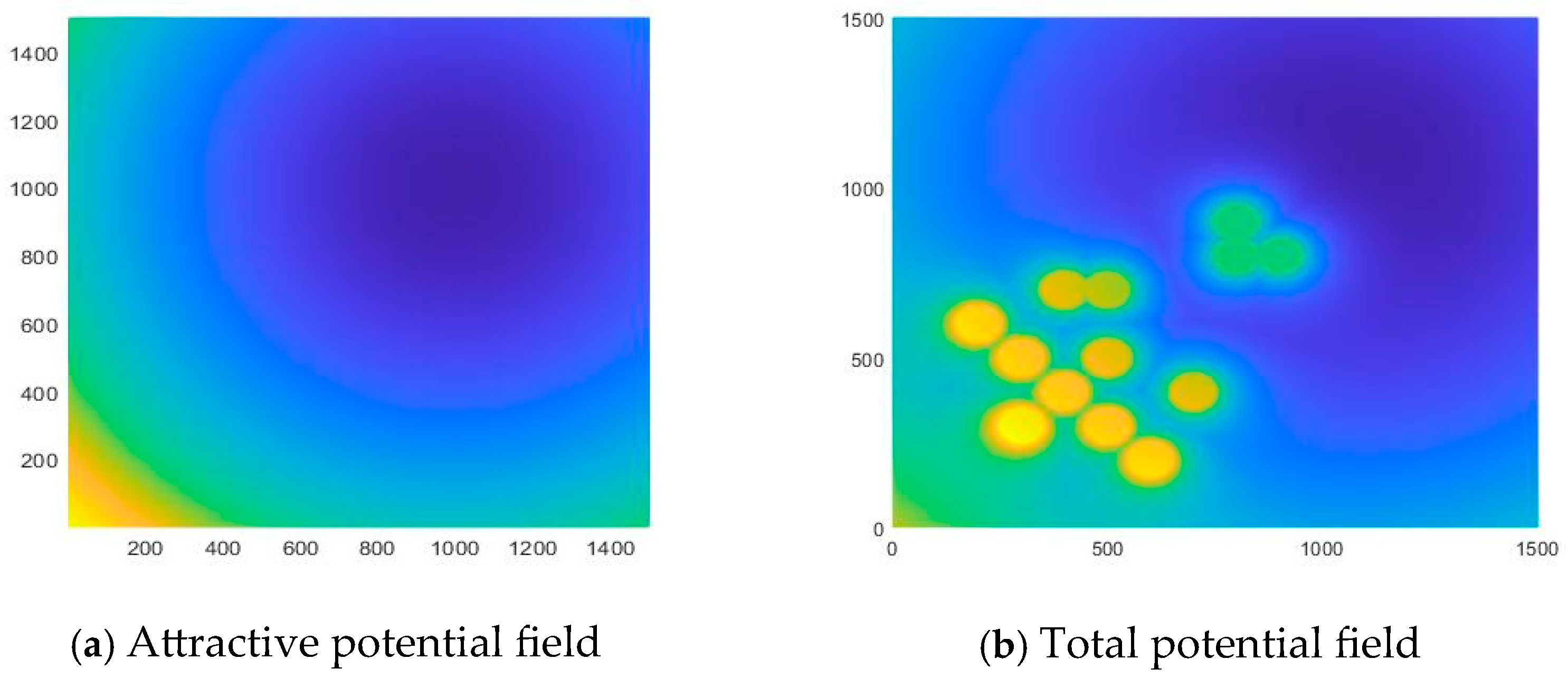

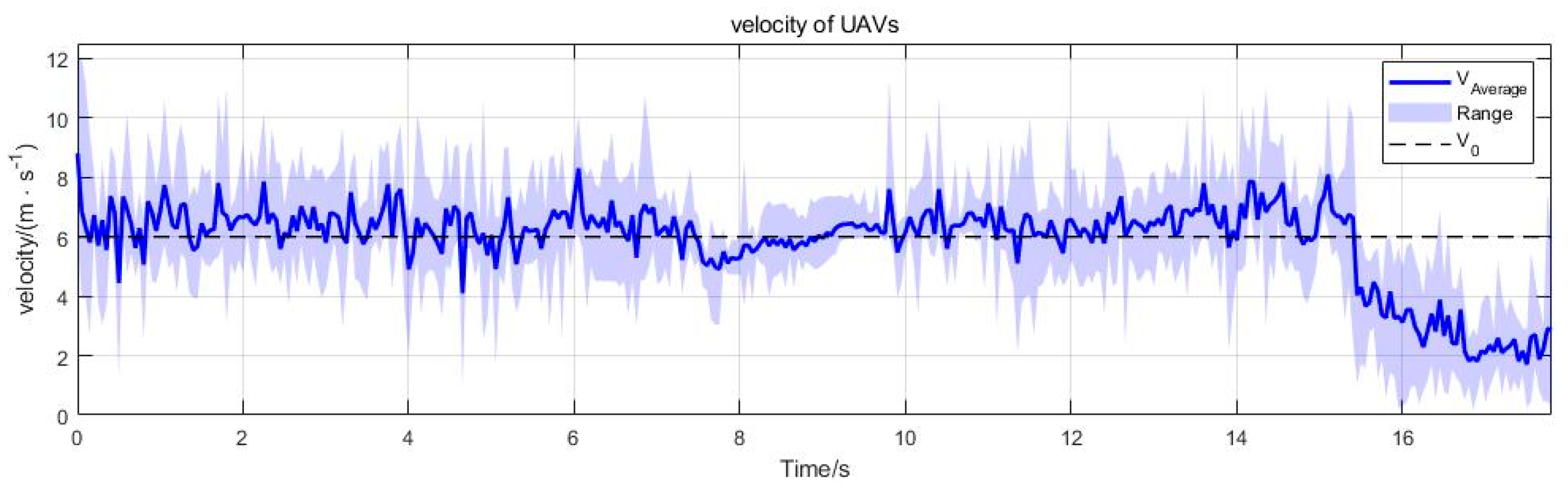

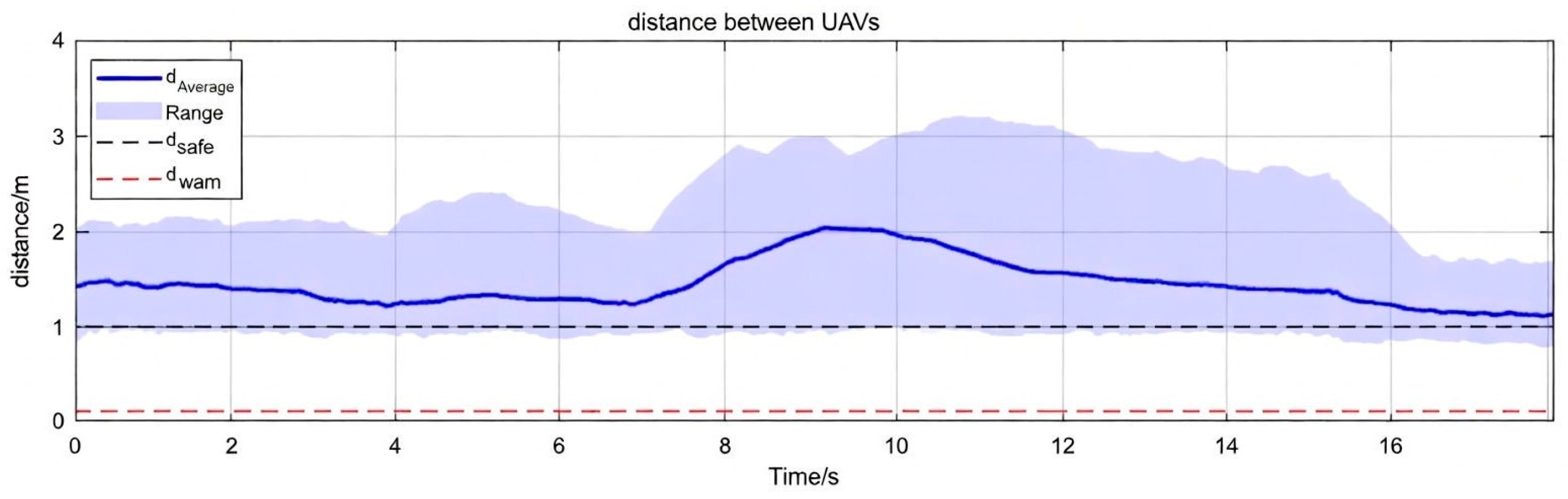

4.2.1. Obstacle Avoidance Through Densely Aligned Obstacles

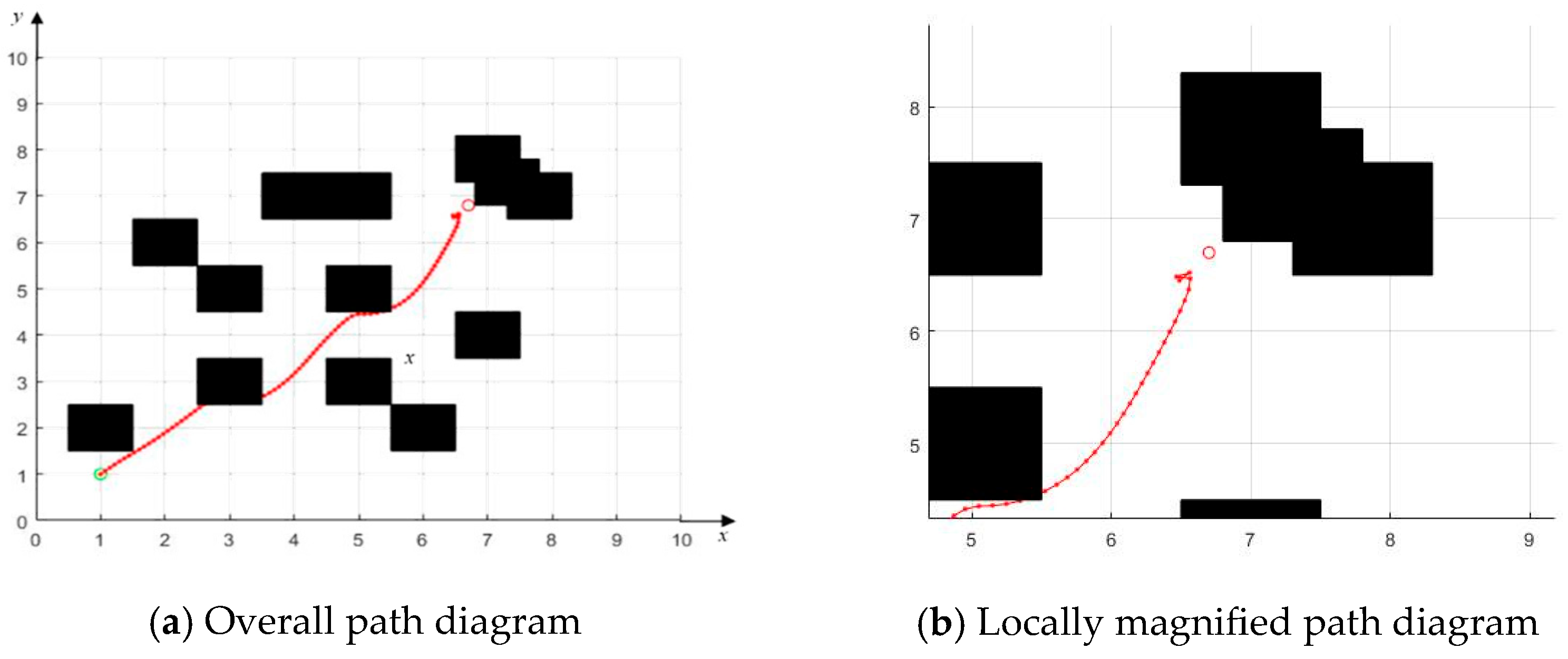

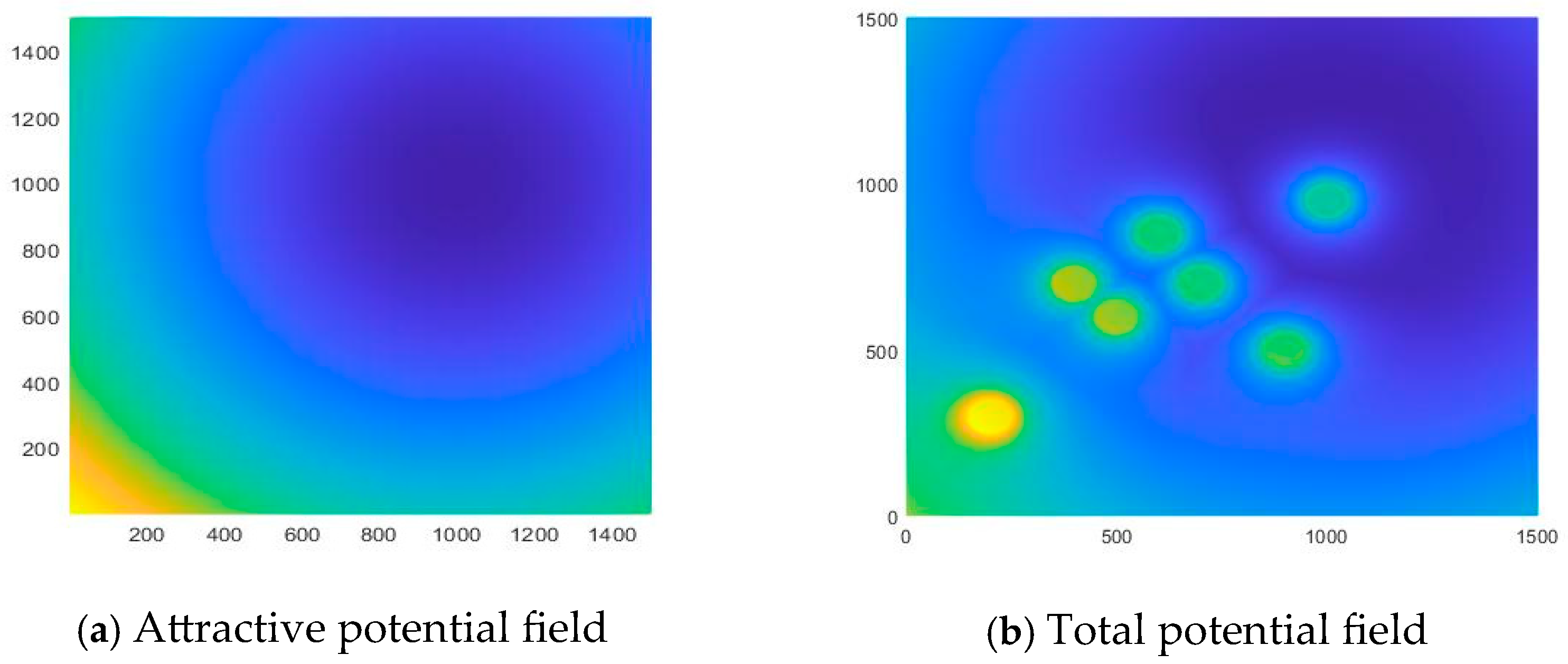

4.2.2. Obstacle Avoidance with the Target Located Behind Obstacles

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, H.J.; Xia, Q.Y.; Ma, X.; Ren, C.; Lu, Y. A Review of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Deployment Optimization in 6G Low-altitude Communication Scenarios. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2025, 46, 531296. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, R.; Gong, X. Predictive Path Planning Strategy for Multi-UAV Systems against Covert Attacks. In Proceedings of the 2024 39th Youth Academic Annual Conference of Chinese Association of Automation (YAC), Dalian, China, 7–9 June 2024; pp. 2297–2301. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ai, J. Adaptive Factor Fuzzy Controller for Keeping Multi-UAV Formation While Avoiding Dynamic Obstacles. Drones 2024, 8, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; He, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Liang, Q. Research on Multi-UAV Obstacle Avoidance with Optimal Consensus Control and Improved APF. Drones 2024, 8, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.W.; Fan, Q.M.; Peng, Y.H.; Yang, H.X. Study on Local Path Planning Based on APF Method. Fire Control Command Control 2024, 49, 177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Kownacki, C. Artificial Potential Field Based Trajectory Tracking for Quadcopter UAV Moving Targets. Sensors 2024, 24, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, W.Q.; Lin, J.Z.; Shao, Z.Y. Path planning of mobile robot based on improved PRM and APF. Meas. Control 2025, 58, 979–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, M.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, X. Integrated the Artificial Potential Field with the Leader-Follower Approach for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Cooperative Obstacle Avoidance. Mathematics 2024, 12, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Zhang, C.; Xia, Y.; Xiong, H.; Shao, X. An Improved Artificial Potential Field Method for Path Planning and Formation Control of the Multi-UAV Systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2022, 69, 1129–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Xu, X.; Pu, Q.; Petrovic, P.B.; Rodić, A.; Wang, Z. A Hybrid Path Planning Method Based on Improved A* and CSA-APF Algorithms. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 39139–39151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Shen, P.; Zhang, P.; Li, Y.; Ma, T.; Han, Y. Path Planning of Underwater Terrain-Aided Navigation Based on Improved Artificial Potential Field Method. Mar. Technol. Soc. J. 2019, 53, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.W.; Gao, B.B.; Wang, P.F.; Liu, Y.N.; Li, Y.M.; Li, P.Q. Research on UAV Formation Obstacle Avoidance Flight Based on Neural Network Adaptive PID Control. Unmanned Syst. Technol. 2022, 5, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, H.; Zhang, J.; Yan, Z.; Yin, B.; Liu, S.; Bai, T.; Wang, D. New multi-UAV formation keeping method based on improved artificial potential field. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2023, 36, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LV, Z.H.; Liang, X.L.; Rwn, B.X. A Real-Time Barrier Avoidance Algorithm for UAV Based on Fuzzy Neural Networks. J. Air Force Eng. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 22, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Yang, F.; Yang, J.; Kang, X. 3D UAV Path Planning via Potential Filed-Imitation Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 43rd Chinese Control Conference, Kunming, China, 28–31 July 2024; pp. 4742–4748. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Shen, Y.; Dai, N.; He, B. Multi-AUV Cooperative Control and Autonomous Obstacle Avoidance Study. Ocean Eng. 2024, 304, 117634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Li, D.; Yang, K.; Deng, H. Multi-Robot Obstacle Avoidance Based on the Improved Artificial Potential Field and PID Adaptive Tracking Control Algorithm. Robotica 2019, 37, 1883–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Lu, J.; Cao, B.; Sun, J. A Novel Robust Hybrid Control Strategy for a Quadrotor Trajectory Tracking Aided with Bioinspired Neural Dynamics. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.L.; Cui, L.K.; Hu, X.Y.; Hu, G.; Wang, H. Obstacle Avoidance and Formation Control of Multiple Unmanned Vehicles in Complex Environments based on Artificial Potential Field Method. Chin. J. Eng. 2025, 47, 364–373. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.Y.; Zheng, E.H.; Qiu, X. 3D UAV Trajectory Planning Based on Optimized Bidirectional A* and Artificial Potential Field Method. J. Air Force Eng. Univ. 2024, 25, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J.; Park, C. Collision avoidance control for formation flying of multiple spacecraft using artificial potential field. Adv. Space Res. 2022, 69, 2197–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasser, M.; Shalash, O.; Ismail, O. Optimized Decentralized Swarm Communication Algorithms for Efficient Task Allocation and Power Consumption in Swarm Robotics. Robotics 2024, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seisa, A.S.; Lindqvist, B.; Satpute, S.G.; Nikolakopoulos, G. An edge architecture for enabling autonomous aerial navigation with embedded collision avoidance through remote nonlinear model predictive control. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2024, 188, 104849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.F.; Fu, Y.J.; Zhang, W.P.; Zhang, H. Algorithm and Semi-physical System Simulation for Command Intent Recognition of UAV in Low-resource Environment. J. Syst. Simul. 2024, 36, 2894–2905. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.L.; Wu, F.G.; Zheng, C.C.; Li, H. UAV Path Planning Based on Optimized Artificial Potential Field Method. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2023, 45, 1461–1468. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Xie, Y.Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, W. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Path Planning Method Based on Motion Prediction and Enhanced APF. Electron. Meas. Technol. 2023, 46, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter Category | Parameter Description | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potential Field Gains | Gravitational potential field gain | K | 100.0 |

| Repulsive gain (environmental obstacles) | 50.0 | ||

| Repulsive gain (intra-formation UAVs) | - | 10.0 | |

| Virtual target point gain | 10.0 | ||

| Safety Thresholds | Minimum safe distance (UAV–obstacle) | - | 0.5 m |

| Minimum safe distance (intra-formation UAVs) | - | 1.0 m | |

| Simulation Basics | Iteration step size | - | 0.01 s |

| Data sampling interval | - | 0.01 s | |

| Algorithm Controls | Virtual target position function parameter | 5.0 m | |

| Local optima detection threshold | <0.1 N |

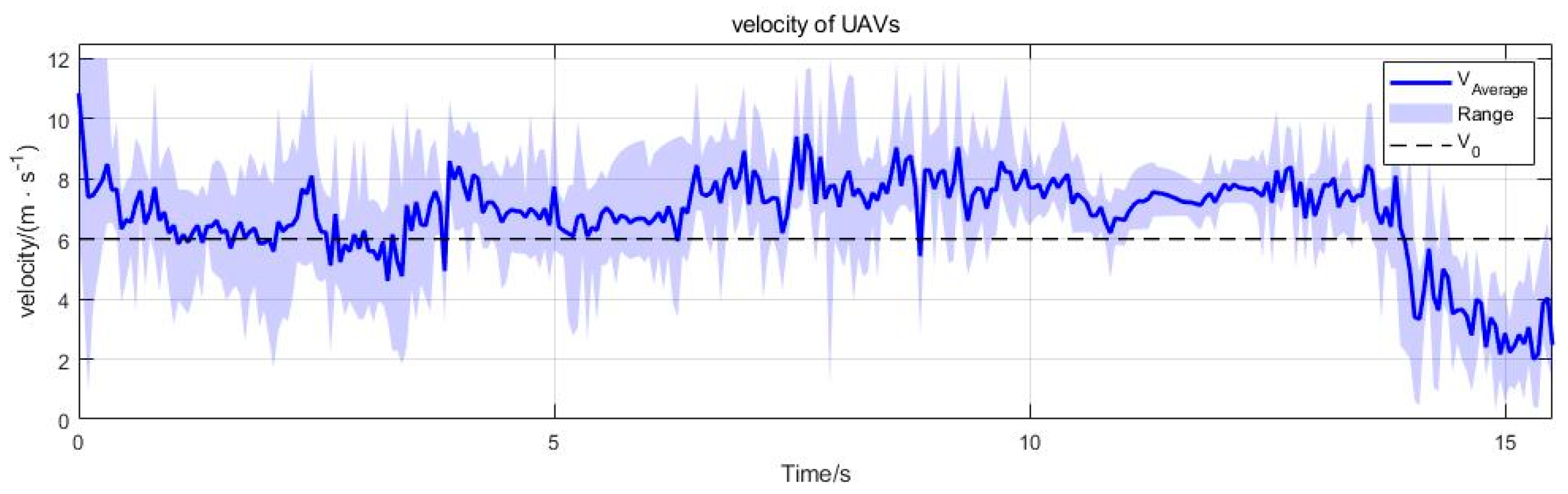

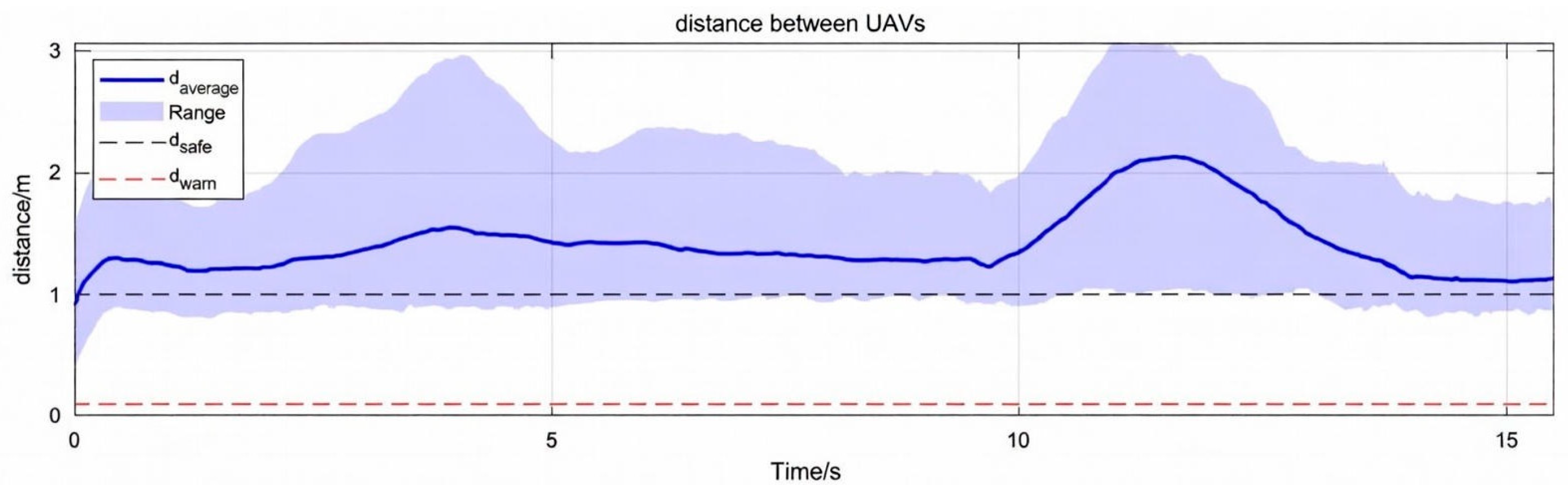

| Performance Index | Proposed Method | Comparison Method |

|---|---|---|

| Target attainment rate | 100% | 0 |

| Mean value of minimum safe distance from obstacles | 0.6 m | 0.3 m |

| Mean value of minimum safe distance in formation | 1.2 m | 0.2 m |

| Effective path length (relative value) | 1.0 (benchmark) | 1.076 (not trapped in local optimal segment) |

| Average task completion time | 15.2 s | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Han, Y.; Guo, L.; Zhao, C.; Yuan, M.; Chen, P. Collaborative Obstacle Avoidance for UAV Swarms Based on Improved Artificial Potential Field Method. Eng 2026, 7, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010010

Han Y, Guo L, Zhao C, Yuan M, Chen P. Collaborative Obstacle Avoidance for UAV Swarms Based on Improved Artificial Potential Field Method. Eng. 2026; 7(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Yue, Luji Guo, Chenbo Zhao, Meini Yuan, and Pengyun Chen. 2026. "Collaborative Obstacle Avoidance for UAV Swarms Based on Improved Artificial Potential Field Method" Eng 7, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010010

APA StyleHan, Y., Guo, L., Zhao, C., Yuan, M., & Chen, P. (2026). Collaborative Obstacle Avoidance for UAV Swarms Based on Improved Artificial Potential Field Method. Eng, 7(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010010