1. Introduction

With the development of the automotive industry and increasing consumer demands for driving quality, Noise, Vibration and Harshness (NVH) performance has become one of the core metrics for evaluating vehicle comfort [

1]. Among various NVH factors, low-frequency noise (typically in the 20–200 Hz range) poses particular challenges due to its long wavelength, strong penetration capability, and difficulty in being effectively absorbed by conventional sound-absorbing materials [

2,

3]. This type of noise can easily cause passenger discomfort, including discomfort such as pressure, irritation, and fatigue, significantly reducing long-distance driving comfort and potentially affecting driving safety [

4,

5]. Consequently, effective control of low-frequency cabin noise represents a critical challenge in enhancing overall vehicle NVH performance.

In the 1990s, Van der Linden and Varet [

6] conducted a contribution analysis of in-vehicle low-frequency noise. By using an experimental method combined with a calculation method for quantifying airborne noise sources, they obtained the contribution of vehicle body panels to in-vehicle noise and the sound pressure contribution near specific field points [

7,

8]. Among various noise sources, structure-borne noise induced by engine excitation constitutes one of the primary contributors to low-frequency cabin noise, particularly in conventional internal combustion engine vehicles [

9,

10]. During engine operation, periodic combustion forces, reciprocating inertial forces, and rotational imbalance forces are transmitted through the powertrain mounting system to the vehicle body structure, exciting vibrations in body panels (such as floor panels, firewalls, and dash panels) [

11]. These vibrating panels subsequently radiate noise into the cabin acoustic cavity, forming what is known as “structure-borne noise” [

12,

13]. Engine excitation exhibits distinct order characteristics and operational condition dependence (e.g., idle, acceleration, cruising). Its fundamental frequency and harmonic components often couple with body structural modes and acoustic cavity modes, generating prominent noise peaks at specific frequencies that become major disturbances to ride comfort [

14]. Precisely analyzing the cabin’s acoustic response characteristics under engine excitation and identifying key noise-radiating panels serve as essential prerequisites for implementing targeted noise reduction measures, such as dynamic vibration absorbers [

15]. This analytical approach holds significant engineering application value for NVH optimization.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, with increasing demands for vehicle comfort, NVH analysis has become a crucial aspect of vehicle development. Numerous innovative vibration and noise analysis methodologies have been proposed. In 2025, Kumar’s team [

16] used a dual-channel noise acquisition device to collect the noise from the automotive powertrain and conducted active noise control experiments. They carried out a comparative study on the noise cancellation results through objective evaluation and subjective human assessment, and utilized active noise reduction equipment to mitigate the interference of powertrain noise on the in-vehicle noise environment. In 2012, Sung et al. [

17] developed a comprehensive secondary transfer path analysis theory based on panel contribution analysis using coupled body-acoustic cavity models, which was successfully applied to solve practical vehicle noise issues. In 2014, Li Wei et al. [

18] proposed a smoothed finite element method for solving structural-acoustic coupling problems, with numerical analysis verifying that this method effectively improves the solution accuracy of coupled systems. In 2021, Zhang Jie [

19] adopted an analytical and mathematical approach based on modal expansion method and impedance mobility techniques to study the structural-acoustic coupling mechanism between two adjacent flexible panels and an enclosed cavity, discovering that the structural-acoustic coupling effect primarily influences the low-order modes of the coupled system. Tang et al. [

20] predicted high-frequency vibration and noise in vehicles by establishing a statistical energy analysis model for automotive vibration noise, and conducted a comparative analysis of noise characteristics in cockpit subsystems between two vehicle models. Chen et al. [

21] measurements of body vibration and sound pressure excitation were conducted under various operating conditions. The study further performed energy transfer path analysis to identify the subsystems contributing most significantly to interior noise, and based on these findings, proposed two optimized noise reduction solutions. Gao Pu et al. [

22] employed a closed-loop coupling analysis model for brake noise, focusing on the vibration energy distribution characteristics of brake discs while revealing the vibration energy flow patterns and transfer paths at friction coupling interfaces, and finally verified the reliability and accuracy of the calculations through brake disc vibration energy balance analysis.

While PACA and vibro-acoustic coupling methods have been widely applied to passenger cars and aircraft, few studies address heavy armored vehicles with their unique structural stiffness, mass distribution, and auxiliary systems. Experimentally validated PACA studies for such vehicles are particularly scarce. This work addresses this gap by adapting PACA to armored vehicle architecture, validating it against controlled experiments, and providing engineering guidance for targeted noise control.

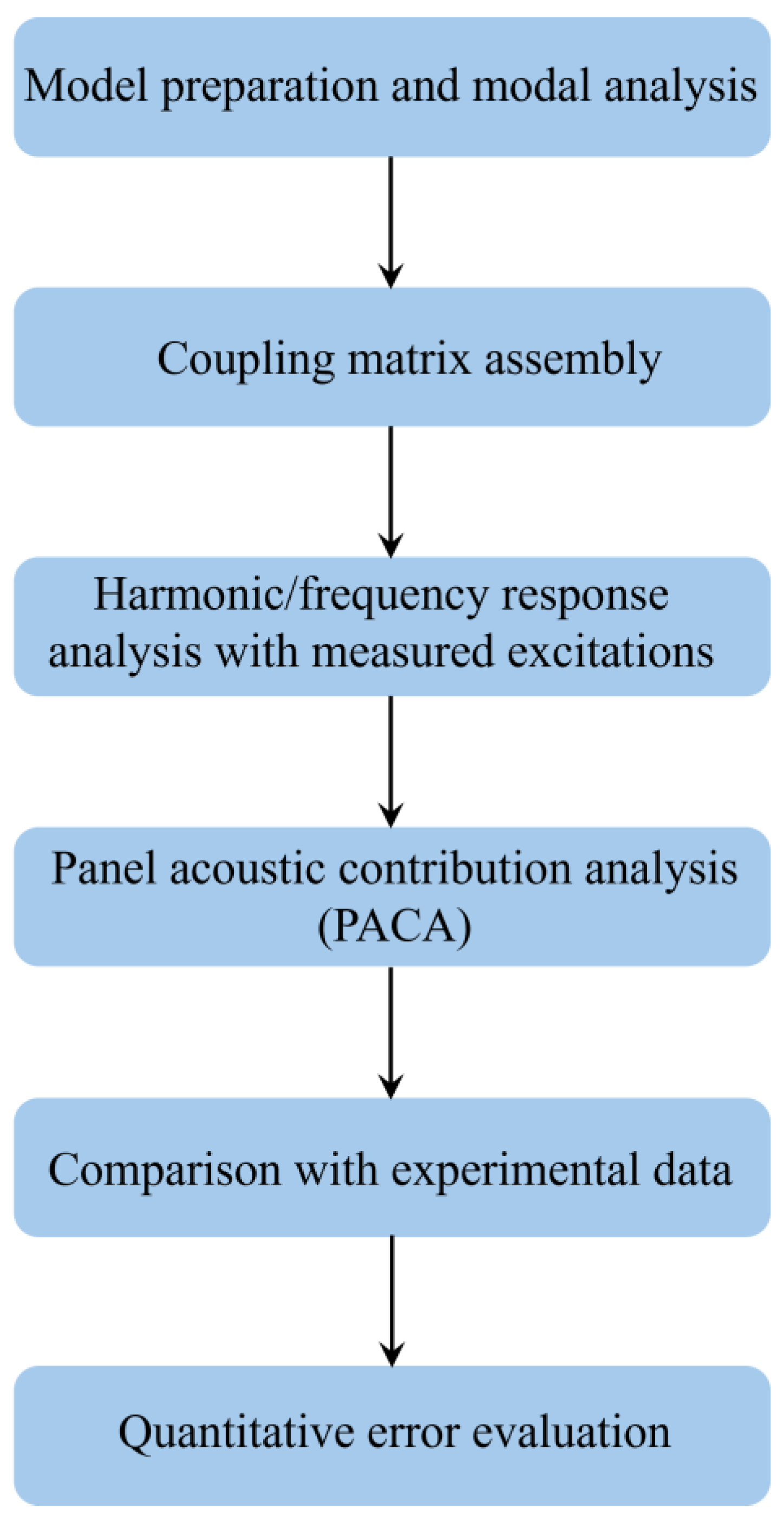

This study investigates the acoustic response characteristics of vehicle interiors based on the dynamic properties of body structural modes and acoustic cavity modes. Focusing on the phenomena of modal frequency shifts and mode shape alterations caused by their coupling effects, we employ panel sound radiation theory and a validated vibro-acoustic coupling model. Through frequency response analysis with engine excitation as input, we identify sensitive frequencies of the coupled system and peak noise frequencies under actual operating conditions. Subsequently, Panel Acoustic Contribution Analysis (PACA) is conducted to quantify the contribution values of various body panels at target frequencies. The obtained acoustic response characteristics and contribution analysis results provide essential preliminary data support for the design of dynamic vibration absorbers.

This study adapts and formalizes the Panel Acoustic Contribution Analysis (PACA) framework specifically for armored special-purpose vehicles, which are rarely addressed in the literature. A condition-invariant structure–cavity resonance at 26.5 Hz is identified and experimentally verified under diverse operating conditions. Based on the validated vibro-acoustic model, we further propose targeted Dynamic Vibration Absorber (DVA) design guidelines for critical panels, providing practical engineering relevance.

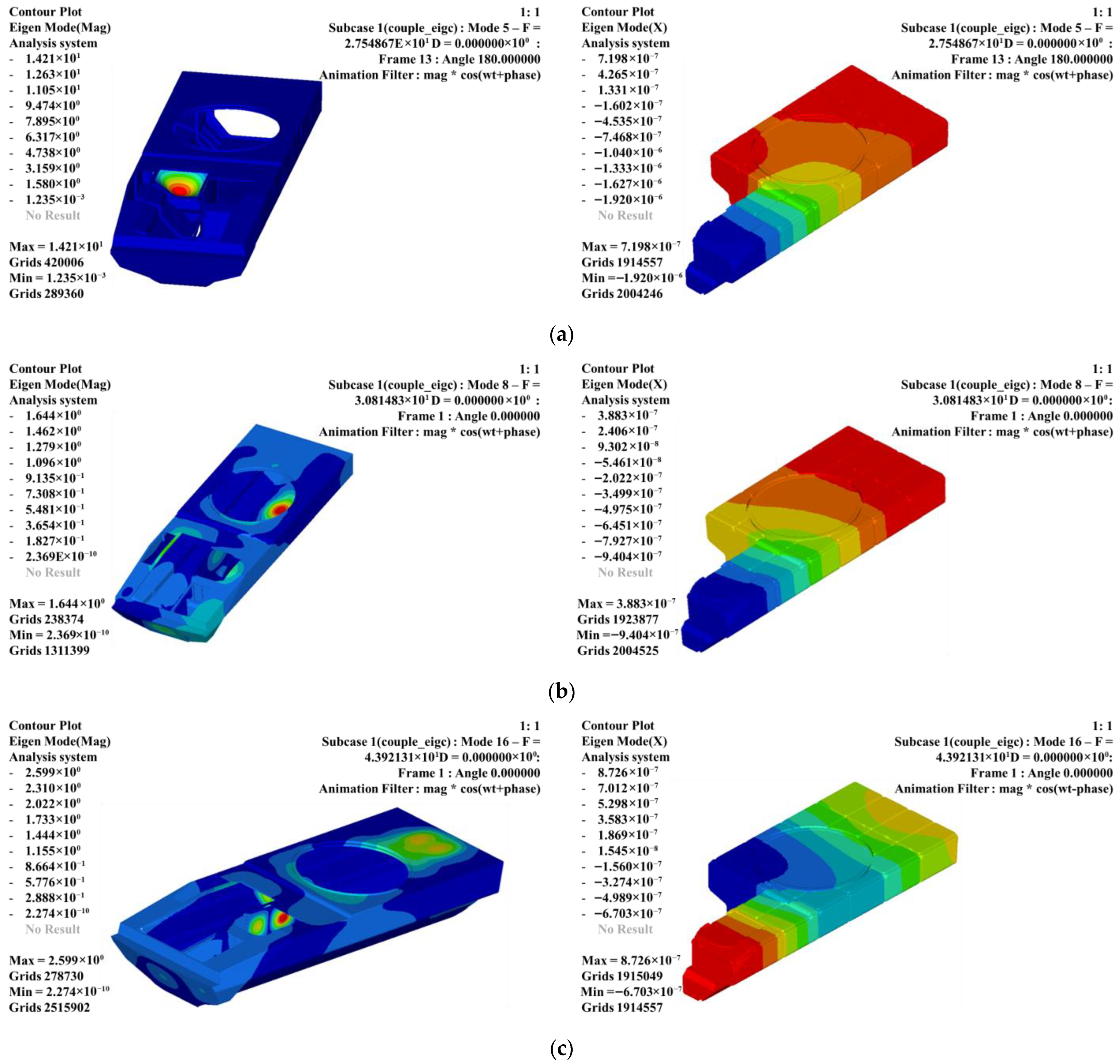

3. Simulation and Experimental Analysis

3.1. Harmonic Response Analysis

Harmonic Response Analysis investigates the steady-state response of linear structures subjected to sinusoidal excitation, aiming to determine response amplitudes and phase angles across frequencies [

30]. This method is derived from the fundamental equations of structural dynamics:

In the equation: M denotes the system’s mass matrix. C represents the viscous damping matrix. K signifies the stiffness matrix. x(t) indicates the displacement response vector.

defines the harmonic excitation force vector. F0 corresponds to the excitation amplitude. ω is the angular excitation frequency.

Substituting the derivatives of each order of the displacement response amplitude, we get

In turn, a proportional relationship exists between the steady-state displacement response amplitude of the system and the excitation amplitude:

H(ω) denotes the system’s Frequency Response Function (FRF), which characterizes the structural vibration behavior while exhibiting dependence on the excitation frequency.

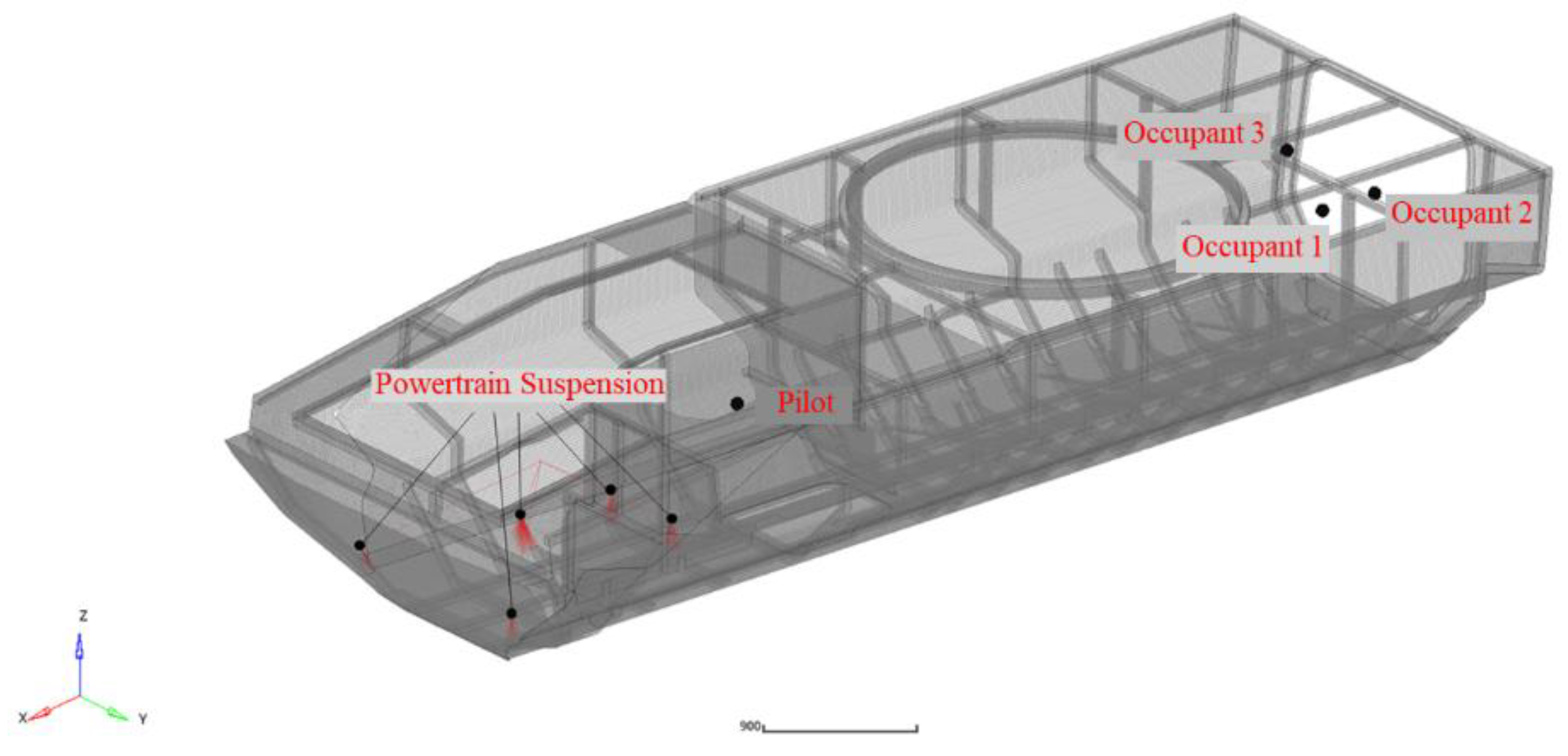

The harmonic response analysis applies excitation at the powertrain’s center of gravity (CG), utilizing unit force excitation along the

Z-axis. Response points are positioned in the vicinity of the driver and occupant head locations. The spatial configuration of excitation and response points is illustrated in

Figure 3.

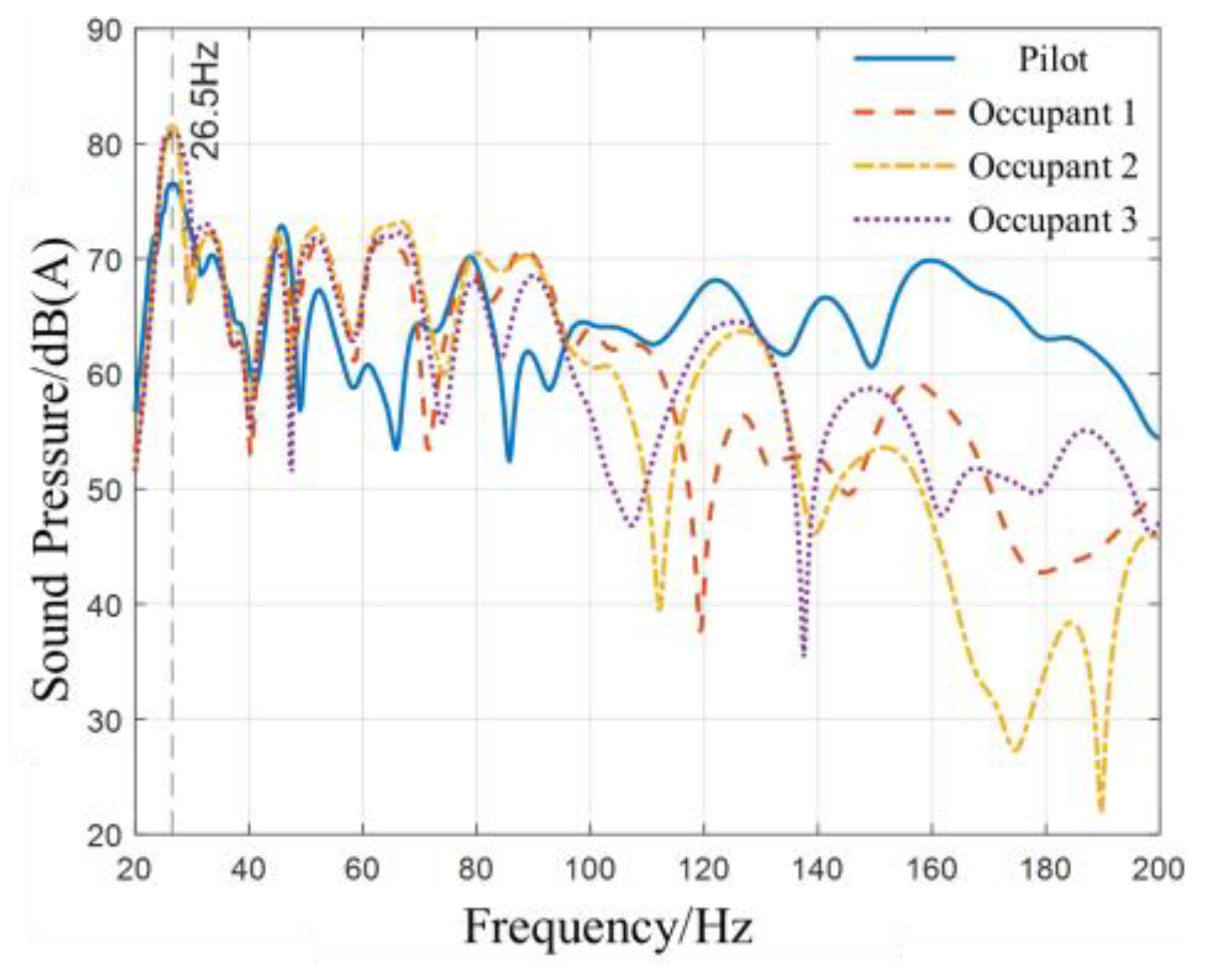

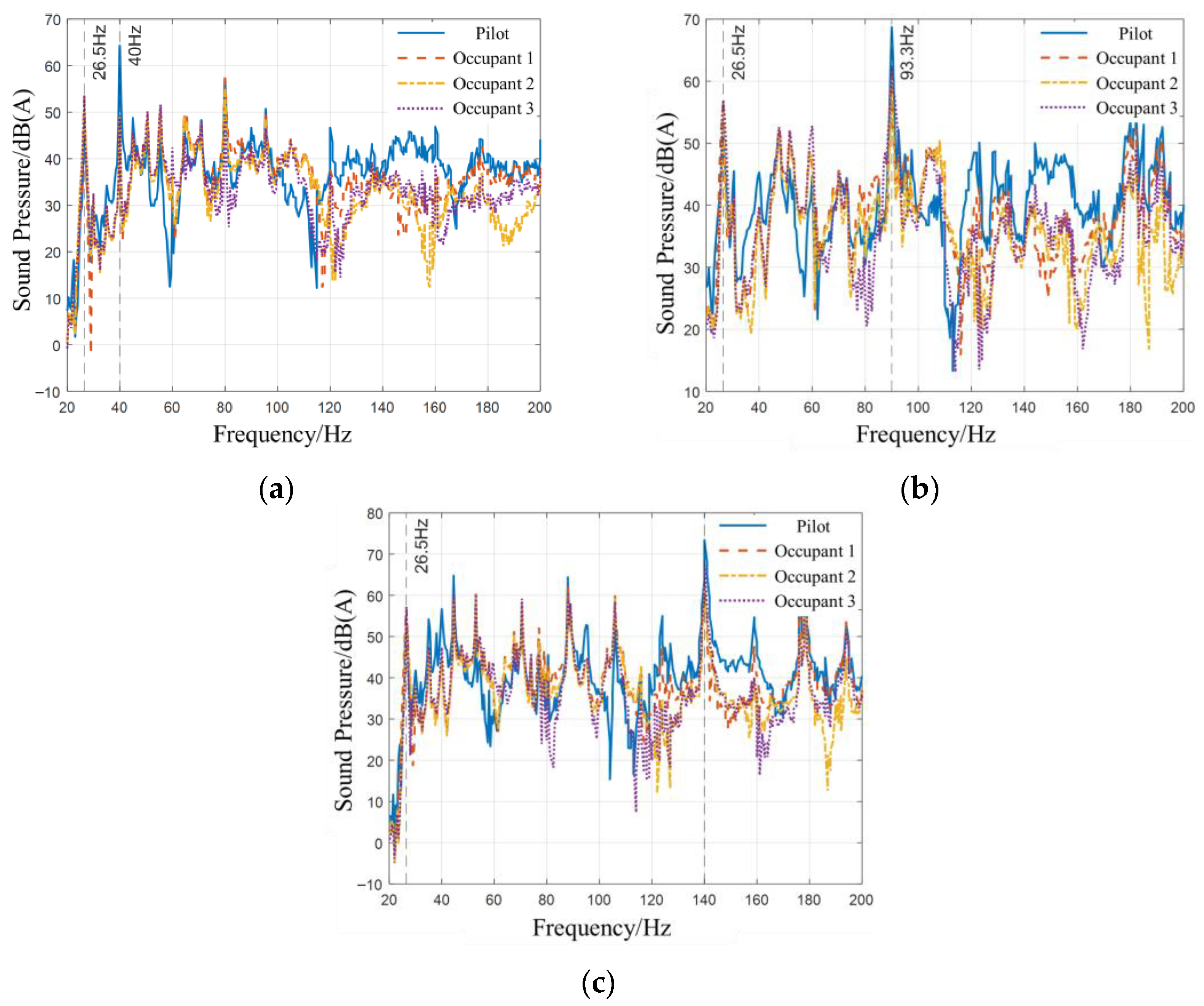

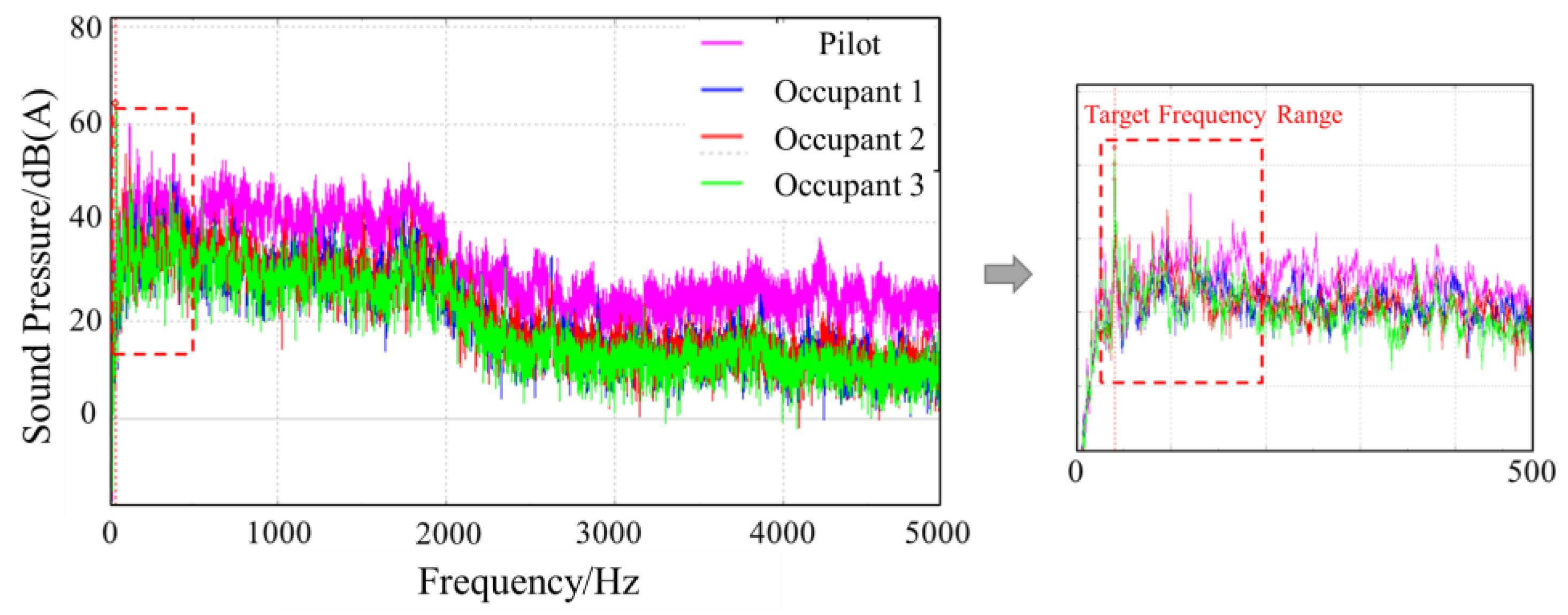

Figure 4 presents the frequency response curves obtained from harmonic response analysis. These curves demonstrate pronounced sound pressure peaks at 26.5 Hz across all four response points near the driver and occupants. This phenomenon indicates that when excitation forces of constant magnitude but varying frequencies are applied at the powertrain center of gravity (CG), the coupled structural-acoustic system exhibits heightened sensitivity near 26.5 Hz during the transmission process: excitation force → structural vibration → acoustic pressure. Cross-referencing the body structure and acoustic characteristics discussed in the text, the 26.5 Hz peak response is attributed to structural panel vibrations exciting the first-order longitudinal acoustic cavity mode, resulting in structural-acoustic resonance.

However, frequency response analyses based solely on unit excitation forces at the powertrain CG cannot accurately replicate actual engine-induced cabin noise responses. To determine authentic acoustic behavior under operational engine excitation, experimentally measured excitation data must be incorporated for further analysis.

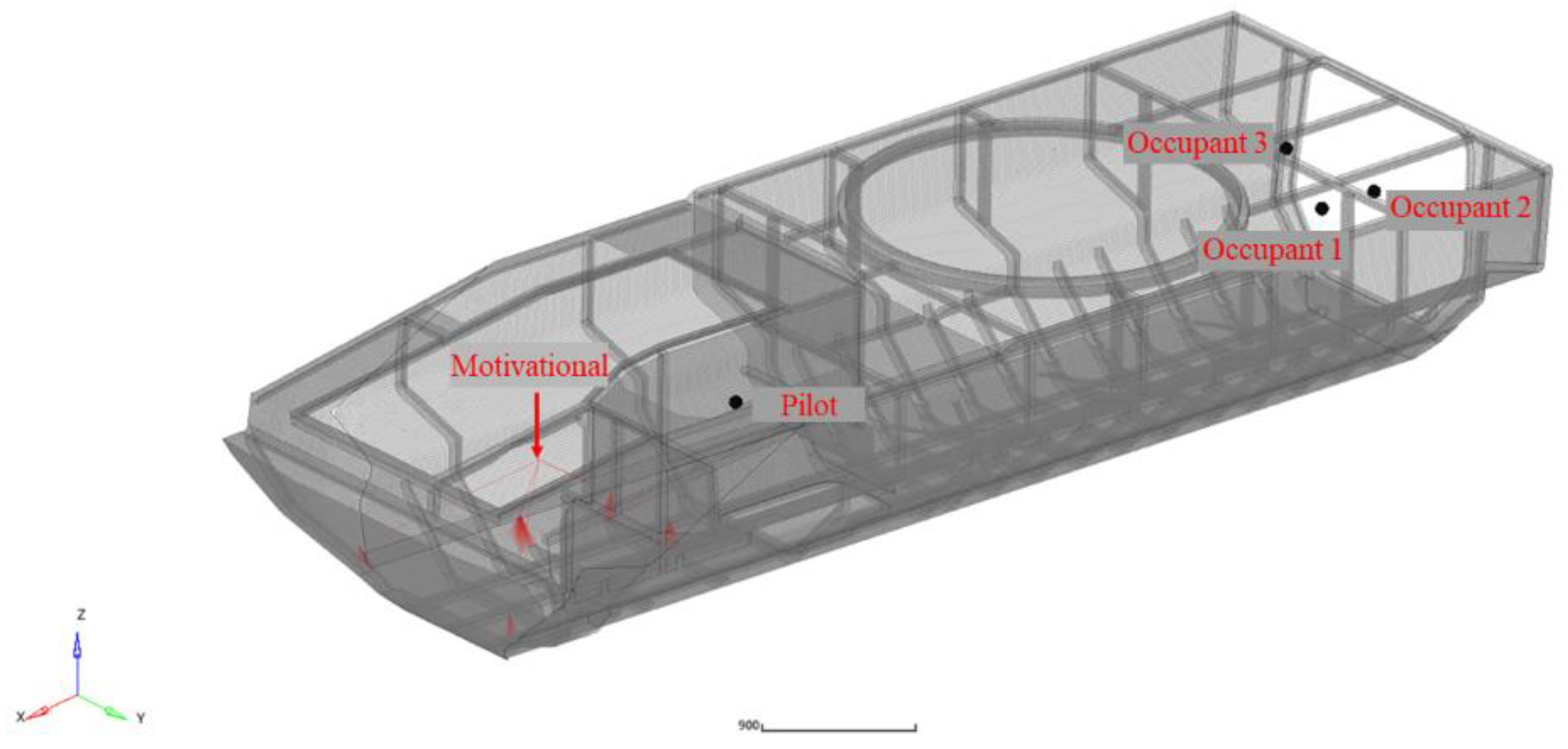

3.2. Simulation of Frequency Response Under Analogue Engine Excitation

The finite element model was developed in HyperWorks/OptiStruct using CQUAD4 shell elements with an average mesh size of 20 mm, resulting in approximately 180,000 degrees of freedom (DOF). The suspension system was represented as flexible mount points, while the powertrain was simplified as a concentrated mass point with applied excitations. The body structure was assumed to be made of armor steel with density 7850 kg/m3, Young’s modulus 2.1 × 1011 Pa, Poisson’s ratio 0.3, and damping ratio 0.015. These specifications ensure reproducibility of the model for future validation and benchmarking.

In the vehicle model under study, the engine connects to the body structure through five mounting points. Experimentally acquired vibration signals from the passive sides of these powertrain mounts serve as input excitations for the body finite element model (FEM). These signals are imposed at the five powertrain mounting locations as power spectral density (PSD) functions. Response points remain positioned at driver and occupant ear reference locations. The spatial arrangement of excitation and response points is illustrated in

Figure 5.

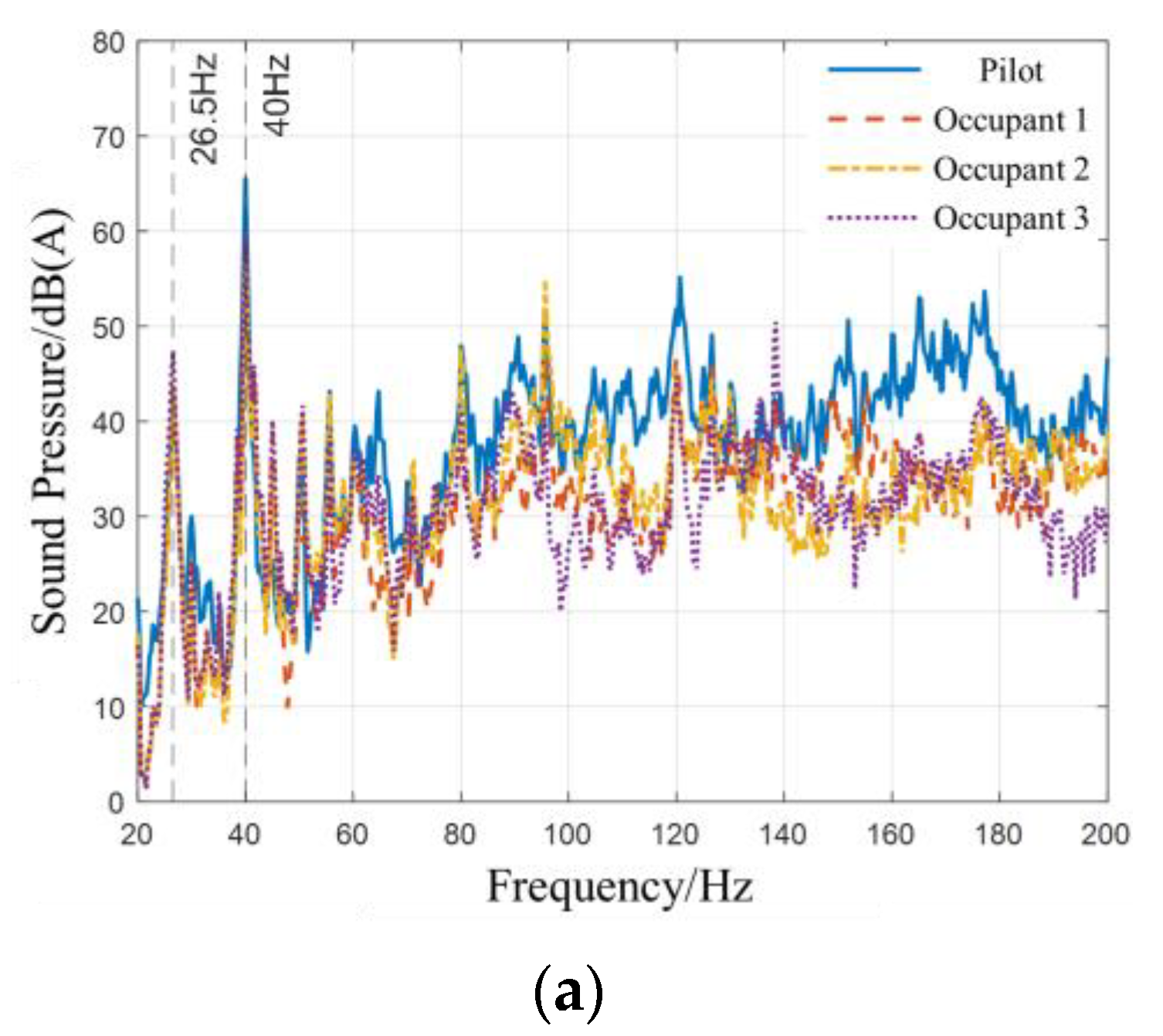

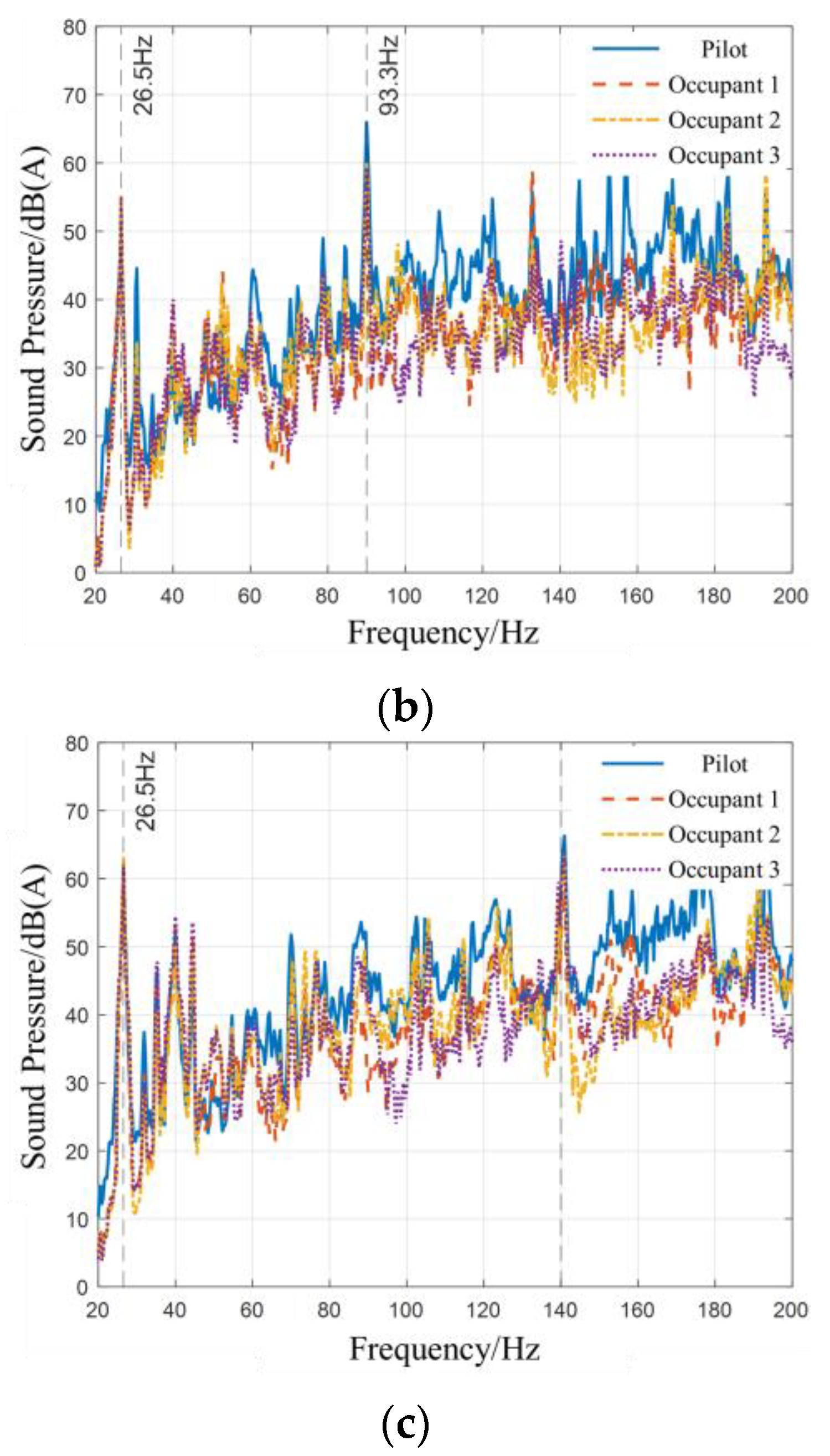

Figure 6 displays the noise frequency response curves at four acoustic response points under three distinct engine operating conditions.

3.3. Real Vehicle Noise Acquisition

The tested vehicle is an 8 × 8 armored special-purpose vehicle with the overall dimensions 8.0 m × 3.0 m × 3.2 m and a gross weight of 36 t. It is powered by a V8 diesel engine (displacement 15.872 L, bore 132 mm, stroke 145 mm, rated power 560 kW, operating range 600–2300 rpm). Tests were carried out in an indoor laboratory at ~25 °C ambient temperature. Background SPL with the engine off was 55–61 dB(A), at least 10–20 dB lower than operating levels, ensuring negligible interference.

Microphones (INV9206, 6.3 Hz–20 kHz, ±2 dB) were installed at four ear-reference positions (driver + three passenger right-ear locations) following ISO 5128:2023 [

31] and GB/T 18697-2023 standards [

32]. Each sensor was calibrated with a reference acoustic calibrator before tests. An LMS SCM05 acquisition system was used for data collection. For each operating condition, three repeated 30 s records were acquired and averaged to improve repeatability. Three steady-state engine conditions were investigated: idle (600 rpm), maximum torque (1400 rpm), and rated speed (2100 rpm). Oil and coolant temperatures as well as stabilization times were recorded: idle (oil 85–95 °C, coolant 85–90 °C, stabilization 1.5–2.5 s), maximum torque (oil 80–90 °C, coolant 80–85 °C, stabilization 3–5 s), and rated speed (oil 75–85 °C, coolant 75–80 °C, stabilization 2–3 s). These conditions were selected as representative of typical mission-relevant operating states.

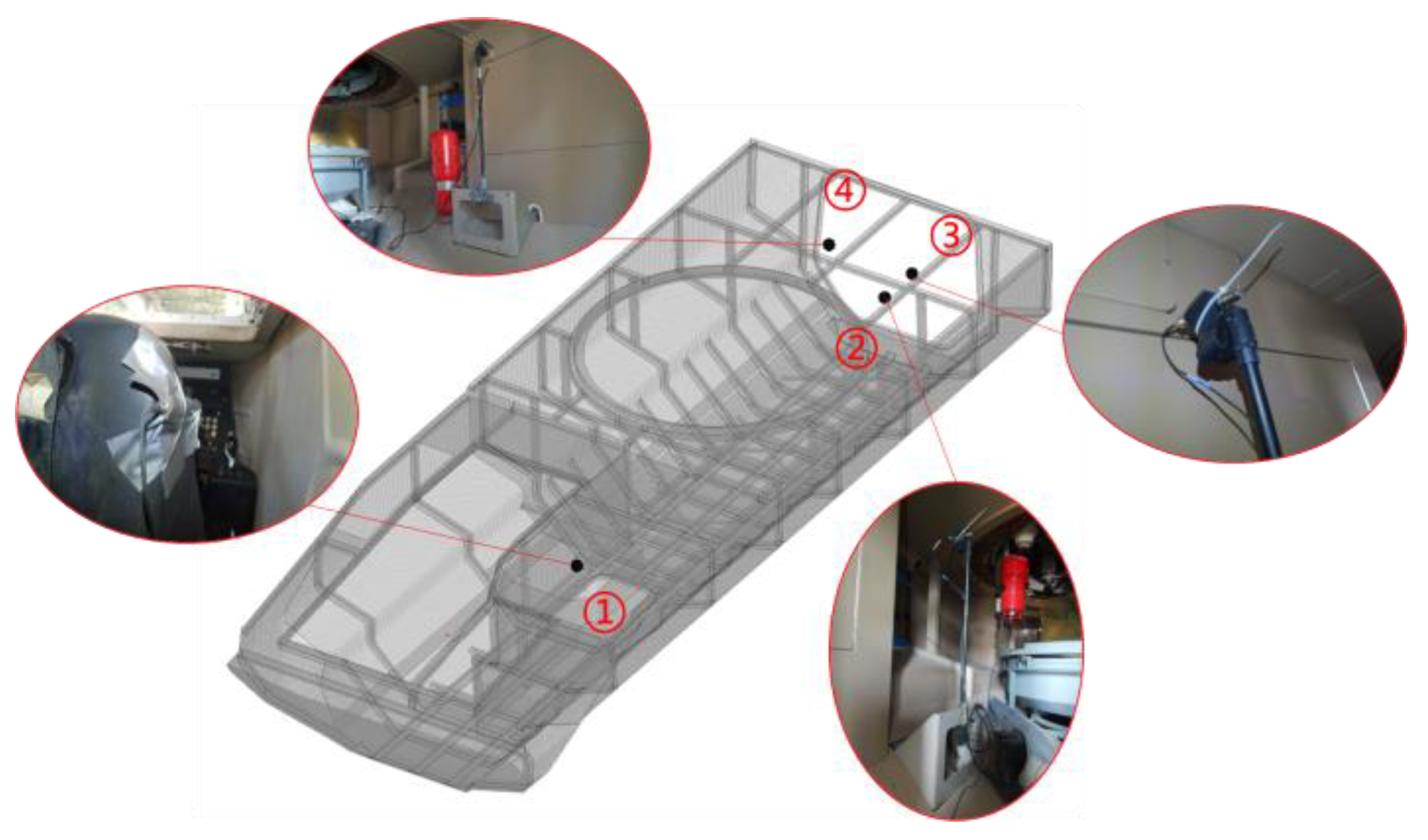

In-vehicle noise characterization tests for the special-purpose vehicle employed pressure transducers to acquire real-time acoustic pressure signals. The instrumentation and sensor specifications, including quantities and models, are detailed in

Table 1.

Four acoustic pressure measurement points were selected for structural noise sampling: at the driver’s head and three occupant head positions. Sensor placement is detailed in

Figure 7. Point ① is positioned near the driver’s right ear, adjacent to the right side of the driver’s seat. Points ②, ③, and ④ are located near the right ears of the respective occupants. Since occupant seats were uninstalled during testing, transducers were mounted on rigid metal rods fixed 700 mm above the nominal seat plane, maintaining >150 mm clearance from body panels.

The noise characterization tests employed three steady-state operating conditions—idle (800 r/min), maximum torque (2100 r/min), and rated speed (2100 r/min)—to represent the special-purpose vehicle’s typical operational states across critical mission profiles.

Noise Test Results

Three consecutive background noise measurements were conducted at all designated points with the engine off and ambient noise below detectable levels. Acoustic signals underwent A-weighting per IEC 61672-1 [

33].

The results (

Table 2) confirmed ambient noise levels were significantly lower than the minimum operational noise, validating negligible interference with acquired data.

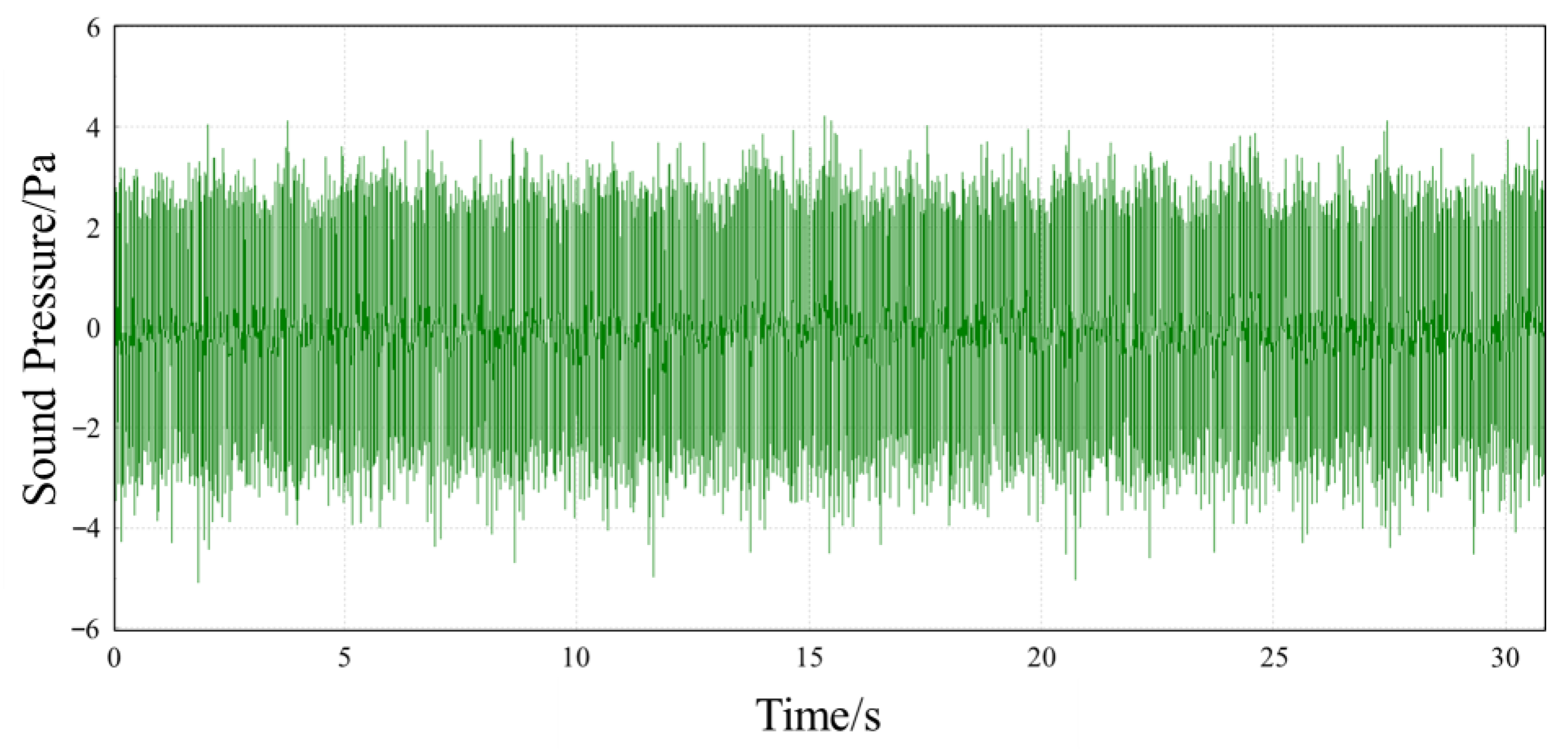

Noise characterization proceeded under multiple engine conditions. Upon reaching thermal equilibrium, 30 s pressure samples were acquired triply per operating state.

Figure 8 illustrates representative time-domain waveforms from idle condition measurements.

3.4. Quantitative Error Analysis of Simulation and Test Results

To further verify the accuracy of the structural-acoustic coupling model in characterizing the structural noise of special vehicles, this section conducts quantitative error analysis from two dimensions (characteristic frequency points and full frequency band) using indicators such as Relative Deviation (RD), dB Difference (ΔSPL), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Coefficient of Determination (R2) based on simulation and test data under the same working conditions and measuring points. The sources of deviation are identified by combining model simplification assumptions and test environments, providing a basis for subsequent model optimization and engineering applications.

3.4.1. Basic Data for Error Calculation

The error analysis is based on the frequency response simulation under simulated engine excitation in

Section 3.2 and the actual vehicle noise test results in

Section 3.3. Three typical working conditions are selected: idle speed (600 rpm), maximum torque (1400 rpm), and rated speed (2100 rpm). The analysis focuses on 4 core response points: the driver’s ear (Measuring Point ①), Passenger 1’s ear (Measuring Point ②), Passenger 2’s ear (Measuring Point ③), and Passenger 3’s ear (Measuring Point ④), with emphasis on data in the low-frequency range of 20–200 Hz. Among them, the characteristic frequency points are selected as follows: 26.5 Hz (system’s inherent coupling frequency), 40 Hz (fourth-order excitation frequency of the engine at idle speed), 93.3 Hz (excitation frequency at maximum torque speed), and 140 Hz (excitation frequency at rated speed). For the full-frequency band analysis, a frequency resolution of 1 Hz is used, resulting in a total of 181 data points.

3.4.2. Quantitative Error Analysis at Characteristic Frequency Points

For the 4 core characteristic frequency points, Relative Deviation (RD) and dB Difference (ΔSPL) are used to quantify local errors, reflecting the model’s ability to capture key noise peaks. The calculation results are shown in

Table 3.

The formula for calculating Relative Deviation is:

The formula for calculating dB Difference is:

In the formulas, SPLsim refers to the simulated sound pressure level (dB(A)), and SPLexp refers to the experimental sound pressure level (dB(A)).

As can be seen from

Table 3, the error indicators at all characteristic frequency points meet the engineering accuracy requirements. The ΔSPL of all measuring points at each frequency point is ≤2.5 dB. Among them, the ΔSPL at the system’s inherent frequency of 26.5 Hz is the smallest (0.67–1.53 dB), and the ΔSPL at the characteristic frequencies of 40 Hz, 93.3 Hz, and 140 Hz under different working conditions is concentrated in the range of 1.63–2.45 dB, all lower than the 3 dB threshold that can be clearly perceived by the human ear. This indicates that the model’s prediction of noise intensity is in good agreement with the actual situation. The RD at all frequency points is ≤3%. Specifically, the RD at 26.5 Hz is generally ≤ 1.8%, and the RD at 40 Hz, 93.3 Hz, and 140 Hz is concentrated in the range of 2.2–2.8%, which is far below the 10% upper limit acceptable in engineering. This confirms that the model has high accuracy in characterizing noise peaks at key frequency points.

From the perspective of differences among measuring points, the ΔSPL and RD at the driver’s ear (Measuring Point ①) are generally higher than those at the passenger measuring points (②–④). For example, under the idle speed condition at 40 Hz, the ΔSPL at Measuring Point ① is 2.34 dB (RD = 2.84%), while the ΔSPL at Measuring Point ④ is only 1.63 dB (RD = 2.27%). This phenomenon is due to the fact that the driver is closer to the power cabin, where the vibration energy transmitted from the engine to the vehicle body through the mounts is more concentrated. As a result, the impact of model simplification on the error in this area is more significant. In contrast, the passenger area has a longer vibration transmission path and more sufficient energy attenuation, leading to relatively smaller errors.

3.4.3. Statistical Error Analysis of Full Frequency Band

For the low-frequency range of 20–200 Hz, continuous sound pressure level data (1 Hz per point, totaling 181 data points) from 4 measuring points under various working conditions are extracted. Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Coefficient of Determination (R

2) are used to quantify the global error, reflecting the model’s ability to fit the overall trend of the frequency spectrum. The calculation results are shown in

Table 4.

The formula for calculating Root Mean Square Error is:

The formula for calculating the Coefficient of Determination is:

In the formulas, N is the number of frequency points, SPLexp is the number of frequency points, is the average value of the experimental sound pressure levels.

As can be seen from

Table 4, the RMSE of the 4 measuring points under all working conditions is ≤2.2 dB. Among them, the RMSE under the idle speed condition is the smallest (1.58–1.85 dB), and the RMSE under the maximum torque and rated speed conditions is concentrated in the range of 1.70–2.12 dB. This indicates that the dispersion between the model’s predicted values and the experimental values in the full frequency band is small, and the overall accuracy is stable. The R

2 of all measuring points is ≥0.89. Specifically, the R

2 of the passenger measuring points (②–④) is generally ≥0.91, and the R

2 of the driver’s measuring point (①) is ≥0.89, all higher than the 0.8 standard for good engineering performance. This confirms that the simulated frequency spectrum is highly consistent with the experimental frequency spectrum in terms of fluctuation trends, and the model can accurately capture the position of noise peaks, amplitude changes, and broadband characteristics in the range of 20–200 Hz.

3.4.4. Analysis of Error Sources

Combining the model construction process and the test environment, the errors mainly come from the following three aspects, all of which are controllable simplification factors rather than inherent flaws of the model.

- (1)

Idealized Simplification of the Simulation Model

In the model, rigid constraints (RBE2 elements) are used for the connection points between the mounts and the vehicle body, while the actual mounts are rubber elastic connections (with a dynamic stiffness of approximately 5 × 105 N/m). This leads to a higher stiffness of the vibration transmission path, resulting in a 1–2 dB lower sound pressure level in the 26.5–40 Hz frequency band in the simulation. Meanwhile, the power assembly and turret are simplified as mass point units (ignoring their own modes), and the first-order bending mode of the power assembly is approximately 50 Hz. At this frequency point, the deviation of the simulated sound pressure level from the experimental value increases by 0.5–1 dB (RD increases to 3.2%).

The simulation only considers the main engine excitations (combustion force, inertia force) and does not include auxiliary excitation sources such as the cooling fan (with a blade passing frequency of 45–60 Hz) and the air pump (with a pulsation frequency of 25–35 Hz). This results in a 1.2–1.8 dB lower simulated sound pressure level in the 30–60 Hz frequency band under the idle speed condition compared to the experimental value, which is also the main reason for the slightly higher RMSE in this frequency band than in other ranges.

- (2)

Test Environment and Operational Interference

Although the background noise of the test (55.82–60.65 dB(A)) is much lower than the noise under the working conditions, there is still environmental vibration interference (such as ground vibration with a frequency of 25–28 Hz) in the low-frequency range of 26.5 Hz. This causes the experimental sound pressure level to be superimposed by 0.5–0.8 dB, increasing the ΔSPL by 0.3–0.5 dB (for example, the ΔSPL at Measuring Point ① at 26.5 Hz increases from 1.23 dB to 1.58 dB).

The sensors are fixed by rigid metal rods (700 mm away from the seat surface), and the metal rods themselves have slight vibrations (the first-order mode of the rod body measured in the test is 38–42 Hz). At the 40 Hz frequency point, this causes the experimental sound pressure level to be 0.8–1 dB higher, increasing the RD at this frequency point by 0.5–0.8% (for example, the RD at Measuring Point ① at 40 Hz increases from 2.84% to 3.52%).

- (3)

Material and Parameter Uncertainties

The set value of the elastic modulus of the vehicle body armor steel is 2.1 × 1011 Pa, while the actual elastic modulus of the material has a fluctuation of ±2% (tolerance range provided by the supplier). This leads to a deviation of ±0.5 Hz in the natural frequency of the vehicle body structure mode (for example, the 26.5 Hz coupling mode shifts to 26.0–27.0 Hz), which in turn causes a sound pressure level deviation of 0.3–0.6 dB.

In the simulation, the structural damping ratio is taken as an empirical value of 0.015. However, due to the influence of welds and coatings on the actual vehicle body, the damping ratio is 0.02–0.025. This results in a slower attenuation rate of the simulated vibration in the high-frequency range (100–200 Hz) compared to the actual situation, and the sound pressure level is 0.8–1.2 dB higher (for example, the ΔSPL at Measuring Point ① at 140 Hz increases from 2.45 dB to 3.05 dB).

5. Conclusions

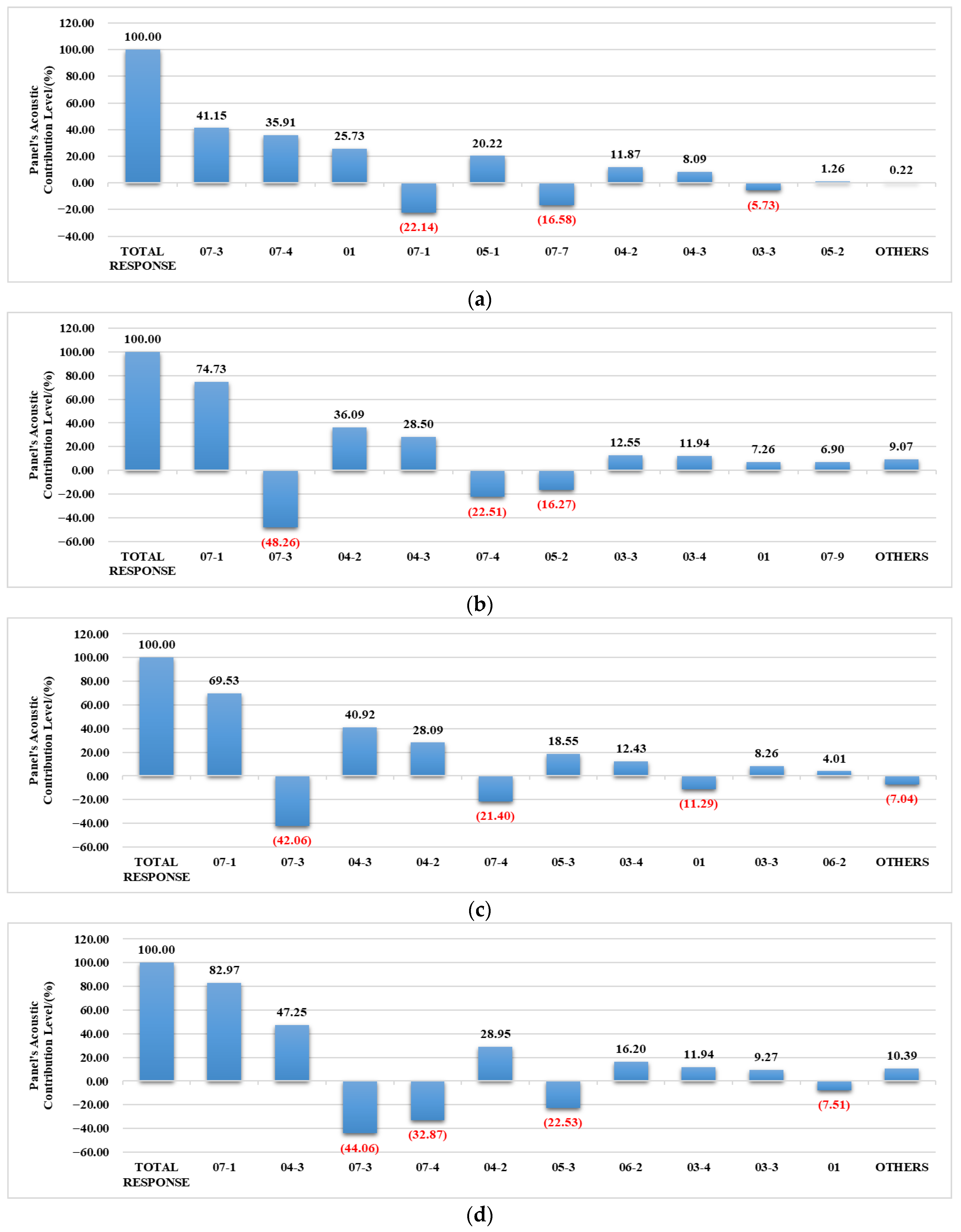

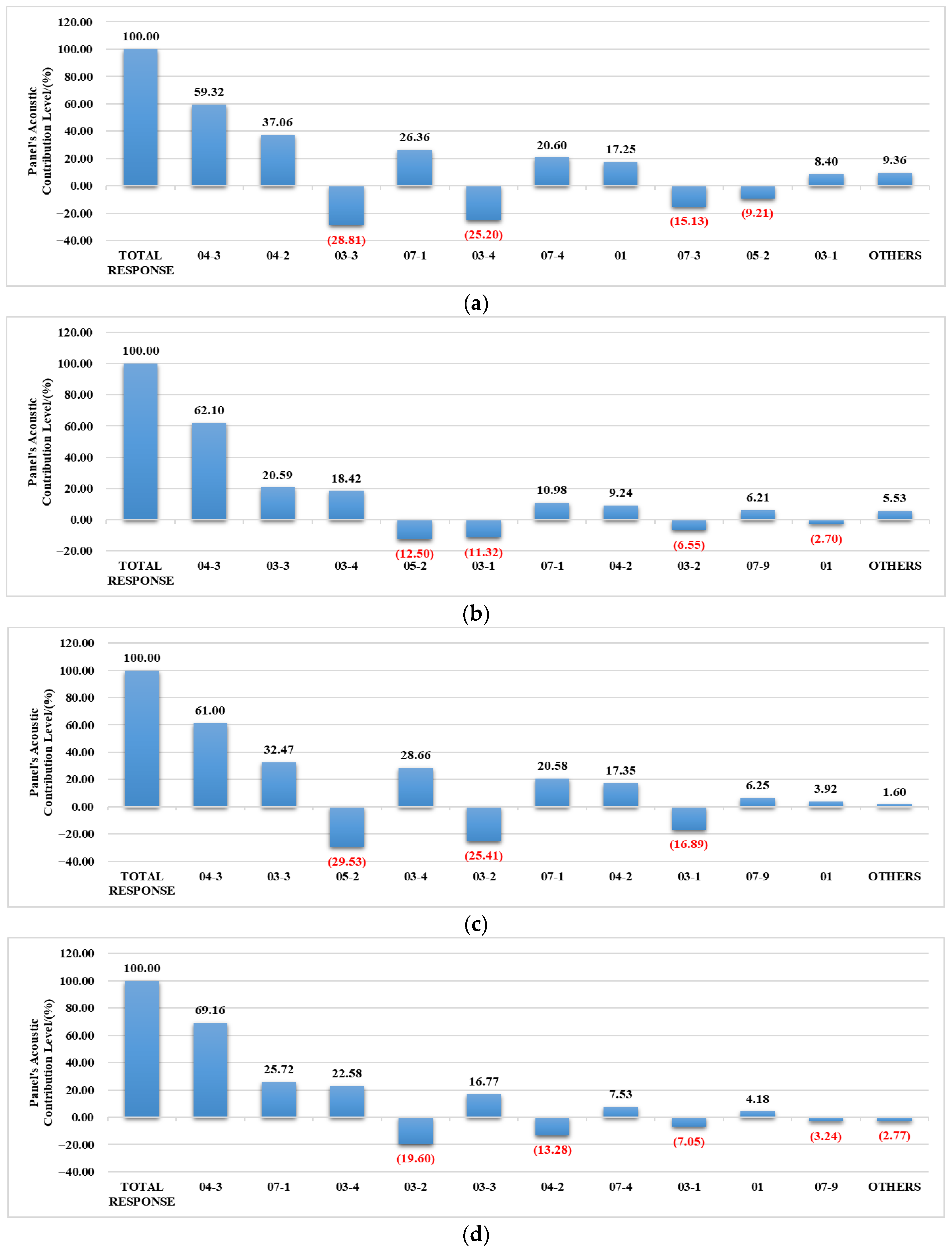

This study investigates noise responses at driver and occupant ear reference points under both unit harmonic force excitation and actual powertrain excitation through an acoustic–structural coupling model based on panel sound radiation theory. Contribution analysis of body panels was performed for dominant noise peak frequencies. Harmonic response analysis reveals significant transmission sensitivity at 26.5 Hz along the powertrain–body–ear vibration path, aligning with structural–acoustic coupling resonance characteristics. Frequency response analysis under powertrain excitation demonstrates strong correlation between operational peak frequencies and excitation characteristics: 40 Hz (idle), 93.3 Hz (maximum torque speed), and 140 Hz (rated speed). Notably, all operating conditions exhibit a pronounced 26.5 Hz peak beyond condition-specific frequencies, consistent with physical vehicle tests and validating the engineering applicability of the vibro-acoustic transmission mechanism. In summary, this work extends the PACA methodology to armored vehicles, experimentally verifies a 26.5 Hz structure–cavity resonance, and provides practical DVA placement guidelines, thereby contributing both theoretically and practically to the field of structural–acoustic dynamic analysis. Based on PACA results, conceptual guidelines for DVA implementation are provided. Panel 07-1 (bulkhead) should be targeted with a DVA tuned to 26.5 Hz, while Panel 04-3 (floor) should be treated with a DVA tuned to 40 Hz. Tuning bands of ±5% are recommended, with damping factors chosen to broaden effective bandwidth. These guidelines, though conceptual, provide clear engineering directions for practical NVH mitigation.

Targeting the coupled model’s sensitive frequency (26.5 Hz) and idle-condition peak (40 Hz), panel contribution analysis identifies Panel 07-1 (partition between powertrain/occupant compartments) as the dominant contributor at 26.5 Hz, and Panel 04-3 (rear section of occupant compartment bottom deck) at 40 Hz. Future work will implement dynamic vibration absorbers (DVAs) on these critical panels for structure-borne noise suppression at target frequencies. Last but not the least, the present study focuses on amplitude-based PACA results. Phase effects, which may alter the superposition of panel contributions, were not included and will be addressed in future work. Incorporating phase-aware PACA is expected to provide deeper insight into noise formation mechanisms and more precise guidance for targeted NVH control.