Abstract

Introduction: The escalating scarcity of skilled healthcare professionals is particularly pronounced within surgical specialties, where the prospect of attracting prospective medical practitioners poses formidable challenges. Throughout their academic journey, students exhibit diminishing enthusiasm and motivation to pursue careers in surgery, including trauma surgery. It is postulated that the caliber of teaching plays a pivotal role in influencing students’ subsequent specialization choices. Methods: This prospective observational study was conducted among a cohort of third-year medical students at the German University Medicine Greifswald. The methodology encompassed the utilization of a self-administered questionnaire to procure data. Results: The study encompassed 177 participants, of whom 34.7% expressed an inclination toward a career in surgery (22.7% in trauma surgery). Participants who reported a favorable impact from the examination course displayed a significantly heightened interest in clinical clerkships within trauma surgery (p < 0.001), and even expressed a contemplation of specializing in orthopedics and trauma surgery (p = 0.001). Logistic regression analysis highlighted that the convergence of practical training and positive role modeling emerged as the most influential factors augmenting the allure of trauma surgery. Conclusions: Evidently, students who gleaned substantial benefits from high-quality practical instruction in trauma surgery exhibited a significantly heightened likelihood of pursuing this domain in their future endeavors. Surgical academic institutions stand to leverage this insight in their strategic planning for attracting and retaining potential residents. Cultivating a positive affinity for trauma surgery should be instilled early in the curriculum, subsequently sustained through ongoing immersive engagement that encompasses professional as well as interpersonal dimensions.

1. Introduction

In the impending years, both the German and international societies are poised to confront significant challenges within the domain of healthcare provision [1]. This development, driven by demographic alterations, is marked by an expanding patient population juxtaposed against a worsening scarcity of skilled healthcare professionals [2,3]. These well-documented trends not only accentuate the competition for recruiting young individuals across diverse medical disciplines [4], but also exacerbate the shortfall of medical practitioners in specific areas, notably within surgical specializations like traumatology [5]. Although explicit benchmarks remain elusive, it is apparent that the under-40 demographic constitutes an increasingly smaller portion of trauma surgeons [6]. This implies that the profession is struggling to entice adequate future practitioners, a concern shared by numerous researchers [7,8]. Despite prevalent interest among students, the translation of such interest into definitive decisions to pursue orthopedics and trauma surgery specialization remains elusive, particularly among female students [9,10]. Once students have kindled their interest in trauma surgery, it becomes paramount to sustain positive exposure to the field throughout the curriculum. This can be achieved through lectures, seminars, and exams, but more effectively through hands-on internships, clinical training, or practical tertials. In 2020, Kasch et al. evaluated the latter’s binding potential and revealed an overwhelming 83.7% eagerness among students to specialize in orthopedics and traumatology [7]. This strategy ensures that interest is not eroded by diverse inputs from competing disciplines and augments the likelihood of students actually selecting orthopedics and trauma surgery.

Other studies have highlighted the critical risk of losing surgical interest [5,11]. While many students exhibit heightened interest in surgery at the outset of clinical education, the interplay of negative experiences and prevailing stereotypes often leads to a shift in preferences toward other fields [5]. Some students even discontinue or switch specialist training contracts if they are dissatisfied with the working environment [3]. Reduced working hours combined with an increased workload—primarily driven by non-medical tasks—is a significant aspect affecting the attractiveness of trauma and orthopedic surgery as a career choice among medical students [4,12]. Additionally, the former attraction associated with surgical practice is purportedly waning in its capacity to captivate interest [13]. Given the limited number of young physicians already certain about their future careers before completing their studies, there lies ample room for influencing this decision [5]. We aim to demonstrate how fruitful university experiences already at an early stage in education can increase the likelihood of swaying students toward specialization.

Prior research has convincingly demonstrated the pivotal role played by role models in shaping the trajectory of medical professionals, especially within the realm of surgical disciplines [8,9,14]. However, the strategic utilization of these role models to consciously allure and retain potential personnel remains an understudied facet. A critical juncture where medical students invariably engage with specialist disciplines, including orthopedics and trauma surgery, is during their educational journey. Hence, it stands to reason that the quality of teaching experienced during medical education, when perceived positively, can exert a discernible influence on subsequent specialization choices [9,15].

A majority of young adults tend to lack concrete career ideas and plans at the juncture of preclinical to clinical education [1]. At that stage of training, we conducted a comprehensive study among medical students at the University Medicine Greifswald, Germany, over a span of three months.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This study was a monocentric, prospective, and observational study conducted at the University Medicine Greifswald during the autumn of 2019. As students transitioned from preclinical to clinical education at this time phase in the medical curriculum, they underwent an examination course, a juncture where theoretical knowledge melds with practical skills. Therefore, this time point represents a formative phase in the development of professional identity and specialty interests. Investigating students at this stage allowed us to assess the potential influence of early clinical exposure. This course, a maiden exposure to clinical practice within the German curricula, is overseen by diverse disciplines. The traumatology examination course involves a rotating team of five physicians, who instruct groups of up to seven students. The curriculum encompasses theoretical sessions, followed by hands-on components aiming to cultivate the ability to discern functional deficits in patients. Typically, students spend a day (comprising four teaching hours) in each discipline. Post-course interviews were conducted on the same day. The inclusion criteria for the study were full participation in the trauma surgery examination course, as well as sufficient proficiency in the German language to complete the questionnaire. Participation was voluntary, and students were informed that their decision to participate or not would have no impact on their academic standing or their participation in the examination course. A total of 180 medical students reflected the full cohort of eligible participants who had exposure to the surgical teaching modules evaluated in this study.

To improve the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions, the study adhered to the TREND statement (see Appendix B and Appendix C).

2.2. Questionnaire Development and Data Collection

The questionnaire used in this study was newly developed for this research. It consisted of 44 questions, including 8 socio-demographic items. The remaining questions focused on course evaluation, students’ previous experiences, teaching quality, and future aspirations, all assessed using a 5-point Likert scale. Two open-ended questions provided an opportunity for participants to elaborate on their experiences. Sociodemographic data included gender, age, marital status, urban or rural backgrounds, and parental academic status (see Appendix A, format is adapted). The content of the questionnaire was developed based on a review of the existing literature on medical education and factors influencing career decisions in surgery. It primarily aimed to test the researchers’ main hypothesis. The questionnaire was not pre-tested for reliability and reproducibility, which represents a limitation of this study. Data collection occurred immediately after the completion of the examination course. Students were asked to complete the questionnaire on the same day, providing real-time feedback on their experiences. The data collected included both ordinal values from the Likert scale (ranging from 1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree) and responses to two open-ended questions. The socio-demographic data gathered included age, gender, marital status, geographic background (rural vs. urban), and parental educational status.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA, Version 26) and R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, Version 4.0.0) [16], conducted at an alpha level of 5%. Pearson’s Chi-squared test was chosen for its suitability in examining the associations between categorical variables. A sufficiently large sample size in each category was proved and confirmed, as an assumption of the Chi-squared test, to ensure the validity of the results. Fisher’s Exact Test was employed when cell values were below n = 5. To quantitatively analyze the associations, the odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated. An OR greater than 1 indicated a positive association between the exposure and the outcome, while an OR less than 1 suggested a negative association. The data, apart from two open text fields, was based on ordinal values from the Likert scale, allowing for a graded assessment of statements from 1 and 2 (Strongly Disagree or Disagree) through 3 (Undecided) to 4 and 5 (Agree or Strongly Agree).

Subsequent data analysis involved multivariable penalized logistic regression on imputed data sets (random forest imputation using Mice package), dichotomizing the data as binomial with distinct “yes” and “no” cut-offs based on question type (positive questions: yes ≥ 4, negative questions: yes ≤ 2 on the Likert scale). We computed four regression models to ascertain the factors predicting participants’ likelihood of pursuing surgical disciplines. The Caret package was used to perform a five-times-repeated five-fold cross-validation framework, including stepPlr for model shrinkage. The dependent variables were general interest in surgery, intentions to pursue further practical education in traumatology, aspirations to become a trauma surgeon, and a positive impact of the course on subsequent specialization choice. All dichotomized responses to the questionnaire were considered as independent variables, including age, sex, marital status, whether the participants had grown up in a rural or urban area, and their parents’ educational status. The final models were generated using the complete data set, and the ORs with the 95% CIs were derived from the regression coefficients. The results are displayed as forest plots.

For a granular assessment of positively evaluated teaching sub-components and their influence on students, we examined the percentage difference concerning the likelihood of later specialization in trauma surgery. Chi-squared tests were employed to compare the distribution of interests in trauma surgery between the groups. Analogously, the willingness to gain further practical experience in this domain was assessed.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

With the inclusion of 177 participants, our survey approached a near-comprehensive coverage of the cohort (n = 180). Merely three students from the entire cohort were absent during the course or abstained from participating in the survey. The surveyed group comprised 63 males and 114 females, with an average age of 23.8 years (SD ± 3.39), spanning from 19 to 38 years.

Regarding preferred specialization, 83 students (46.9%) identified their favored discipline when asked using an open-ended question. Surgery emerged as the most commonly cited subject, while (orthopedics and) trauma surgery accounted for 12.1%. Participants were allowed multiple responses (Table 1).

Table 1.

Ranking of the desired specialties named in an open question with relative frequency among 83 participants who responded to the question. Multiple answers were allowed.

3.2. Subgroup Comparison—Impact of Teaching on Subsequent Specialization Choice

Notably, participants who reported positive influence from the examination course displayed significantly heightened interest in further practical engagement with the subject (OR = 3.4; 95%-CI [1.74–6.60], p < 0.001), exemplified by their inclination toward clinical clerkships or practical experience terms (46.6%), as opposed to the comparison group (20.5%), who did not report such a positive influence. Furthermore, this group was more likely to contemplate selecting the specialization of orthopedics and trauma surgery (33.0% versus 12.5%, respectively; OR = 3.4; 95%-CI [1.59–7.45], p = 0.001).

Exploring these correlations, we also assessed the influence of pre-planned clinical clerkships or practical experience terms. Students within this subgroup expressed more enthusiasm for a surgical specialization, particularly within orthopedics and trauma surgery (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Likelihood of students expressing interest in surgery depending on their plans for further training in traumatology.

Students who had favorable previous experiences prior to the course were significantly more inclined to opt for a specialization in orthopedics and trauma surgery (33.3% versus 18.5%; OR = 2.2; 95%-CI [1.05–4.59], p = 0.034). They also exhibited a significantly greater interest in clinical clerkships or practical experience terms (47.0% versus 28.2%; OR = 2.3; 95%-CI [1.15–4.44], p = 0.017). Though a minor fraction of students indicated prior negative experiences in the field, some within this group expressed positive surprise with the teaching. Notably, 10% more of these students, compared to the comparison group, still considered pursuing the specialization.

3.3. Descriptive Analysis—Overall Interest in Surgery

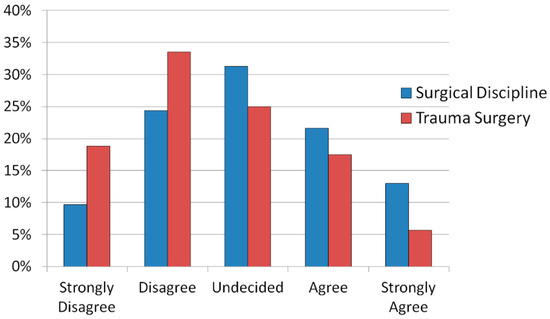

To ultimately gauge the potential appeal of surgery, we queried students regarding their willingness to pursue a surgical specialty in the future, yielding a balanced perspective. Among the 177 participants, 34.7% (rating ≥ 4 on the Likert scale) could envision working within a surgical department, and 22.7% expressed a willingness to undertake specialist training in trauma surgery (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Likert scale-based opinions of the number of students with potential plans to work in a surgical discipline in trauma surgery: total number n = 176 participants.

3.4. Further Statistical Analysis—Significant Coefficients of Logistic Regressions

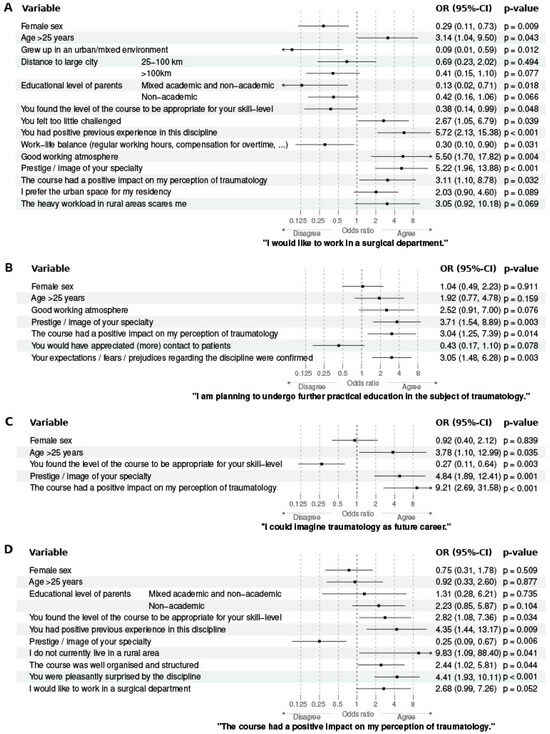

Multivariate analysis through logistic regression provided robust support for the findings outlined earlier. Predictive coefficients were identified for target parameters, generating four distinct models. Those parameters were general interest in surgery, intentions to pursue further practical education in traumatology, aspirations to become a trauma surgeon, and the positive impact of the course on subsequent specialization choice.

The results derived from the logistic regression analysis indicated several key trends. Students who possessed positive prior experiences within the field demonstrated a significantly heightened likelihood of opting for a surgical specialization in the future. Encountering the discipline in a positively surprising manner further amplified this likelihood. Moreover, experiencing a positive influence from the course increased the probability of selecting the orthopedics and trauma surgery specialization (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the four final logistic regressions for (A) general interest in surgery, (B) intentions to pursue further practical education in traumatology, (C) aspirations to become a trauma surgeon, and (D) the positive impact of the course on subsequent specialization choice. The graphs were plotted using the odds ratios (ORs) computed from the regression coefficients, and the bars visualize the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), indicating the strength and direction of the association between the statements on the left and the corresponding target parameters on the bottom. An OR > 1 suggests an increased likelihood of agreement with the target parameter, whereas an OR < 1 indicates a decreased likelihood.

Furthermore, the participants’ age emerged as a noteworthy variable. Older students displayed a more pronounced inclination toward surgery (Figure 2A, OR = 3.14; 95%-CI [1.04–9.50], p = 0.043) and traumatology (Figure 2C, OR = 3.78; 95%-CI [1.10–12.99], p = 0.035).

By employing logistic regression, we have uncovered valuable insights that underscore the pivotal role of positive experiences, course influence, and age in shaping students’ subsequent decisions related to specialization in surgery and traumatology.

3.5. Descriptive Analysis and Subgroup Comparison—Teaching Quality Factors

The analysis employing Pearson’s Chi-squared test to examine positively evaluated components of teaching quality in relation to their impact on the decision-making process toward trauma surgery revealed salient insights (Table 3). Remarkably, a comprehensive theoretical exposition of the content exerted the most substantial influence. While practical experience and patient interaction also demonstrated a positive effect, the course’s organization—whether deemed notably excellent or subpar—had a relatively minimal influence. Intriguingly, the role of effective guidance yielded a paradoxical finding: students who rated their teacher’s support poorly exhibited a greater likelihood of being interested in trauma surgery, contrasting with those who received substantial support. It is pertinent to note that merely 16 out of the 177 participants rated their tutor’s guidance quality as being substandard (≤3 on the Likert scale). However, these trends in the teaching components’ effects only exhibited tendencies, lacking statistically significant differences.

Table 3.

The influence of teaching quality factors on interest in the subject. The outcome investigated was the interest in clinical clerkships/a training term or interest in choosing this specialization. The values are given as percentage differences (∆%) between the groups positive evaluation versus no positive evaluation. Negative values mean that in the group that gave this teaching aspect a lower rating, more students indicated an interest in the subject.

Students who found their course expectations were exceeded demonstrated the most pronounced approval ratings in terms of practical experience and direct patient interaction (Figure 3). An additional insight arose from the logistic regression analysis. Participants who possessed a definite intention to pursue a career as a surgeon perceived the course as somewhat less challenging. Conversely, students disinterested in the surgical field generally considered the course demands to be well-matched to their skill level. Furthermore, the appropriateness of the perceived difficulty had effects on the outcome; students who found the course appropriate felt positively influenced in their interest specifically in orthopedics and trauma surgery.

Figure 3.

Percentage of students who felt positively surprised by the trauma surgery education and gave the individual teaching aspect a good rating ≥ 4 on the Likert scale.

4. Discussion

Our results show that participants who reported a favorable positive impact from the high-quality teaching displayed a significantly heightened interest in further specializing in orthopedics and trauma surgery. Surgical academic institutions should use this opportunity of a positive influence in the early stage to attract potential future colleagues to engage in the surgical field. The most recent literature on this subject is rooted in nationwide cross-sectional surveys conducted over a decade ago [1,4,5]. It becomes imperative to reevaluate and expand upon the insights gleaned from that era, and our study serves as a stepping stone in this direction. By encompassing 177 participants from a cohort of 180 students, we attained an exhaustive coverage of the year’s student body.

4.1. Choice of Specialization

The outcomes of our survey substantiate our initial hypothesis that effective teaching in orthopedics and trauma surgery bolsters the likelihood of students venturing into this field in their future careers. To synthesize the findings, approximately a third of the cohort demonstrates a general interest in surgery. Notably, while half of the students do not consider specialization in orthopedics and trauma surgery, this outcome aligns with expectations since not all participants possess an inherent affinity for a particular field. In terms of preferred future specialist disciplines, only half of the participants provided one or more responses, indicating limited representativeness. Likewise, the statement “I could imagine traumatology as a future career” elicited indecision from about half, representing a group potentially open to persuasion. The sizeable portion of students refraining from specifying a discipline in the open-ended question underscores the substantial contingent still navigating indecision. Thus, we are potentially facing a big group that still can be won over.

4.2. Comparison with Other Data Sources

In comparison with older nationwide surveys, internal medicine emerged as the most coveted specialty, with a prevalence of 42.6% in the study by Gibis et al. [1] and 31.2% in the study by Osenberg et al. [5] (compared to 24% expressing surgical interest). Our study showcased a relatively high surgical interest of 34.7%. The proportion of internal medicine enthusiasts, however, stood at 20.5% in our associated open-ended question. This variance could be attributed to different question formats or, alternatively, might signify that students in the early clinical stages show a heightened inclination towards surgical fields. The divergent findings could potentially be due to cross-sectional surveys encompassing students across all academic years.

Comparing our collected data to figures from the Federal Statistical Office and the Federal Medical Association, it becomes evident that this year’s survey on a small scale reflects the broader picture drawn by nationwide specialist distribution [17]. The merger of trauma surgery and orthopedics in Germany in 2005 complicated reference number searches.

However, this complexity does not undermine the informative value of the research, given the meticulous approach we have taken. Depending on the counting methodology, data from the Federal Statistical Office yields percentages of approximately 5% in both clinical and outpatient settings for the proportion of trauma surgeons within the medical profession [11,18]. Similarly, the German Medical Association’s surveys converge at around 5% [6], in harmony with our student survey results, where 5.7% exhibited a strong resolve towards pursuing trauma surgery. Unfortunately, three years later in the annual count of the German Medical Association, the proportion of trauma surgeons only reached 3.4% [19].

Moreover, recent evaluations show a decreasing interest in surgical disciplines while students progress through medical school. At the beginning of their medical studies, 35% of students initially express an intention to pursue surgical specialization, but this proportion declines substantially to 19% in the further semesters [1]. This tendency underlines the importance of continuously motivating and engaging medical students throughout their education to sustain their interest and commitment in surgery.

4.3. Navigating Challenges and Fostering Interest in Trauma Surgery

While it seems hypothetically promising that we will continue to attract a sufficient number of young entrants, the challenge to ensure patient care persists. The shortage of residents as well as physicians—particularly in surgical disciplines—is a multifactorial issue that cannot be attributed solely to a declining number of doctors. It is also driven by demographic shifts, such as an aging population and the resulting increase in healthcare demand, which aggravates the personnel deficiency. Moreover, workforce needs vary significantly across regions and time frames.

Analyzing our collected data, it is important to note that many parameters exhibited mutual influences. For instance, students with a strong interest in pursuing further practical education in trauma surgery were also inclined to contemplate it as a future career option, aligning with our main hypothesis. This correlation logically stems from the fact that these students have already cultivated an interest in the subject. It signifies not that basic trauma surgery knowledge holds value for all students and that internships in this domain should therefore be conducted, but that there is a genuine interest in trauma surgery to be found among some students.

4.4. Problematic Aspects in Recruitment

Our study’s results suggest that effective teaching can indeed counterbalance negative past experiences and retain staff. The impact of positive surprises has been substantiated, and the correlation between the confirmation of expectations/prejudices regarding the discipline and both interest in further practical education and surgical specialization implies that predominantly positive biases are prevalent among Greifswald students. This likely indicates that a positive image of surgery is predominant among the majority of students. Nevertheless, this assertion is phrased rather vaguely, urging future studies to elucidate these “expectations/fears/prejudices” in more specific terms.

4.5. Impact of Different Teaching Quality Factors

In addition to confirming the main hypothesis that effective teaching can influence students’ later specialization choices, we analyzed the individual factors of teaching quality being positively assessed in relation to their relevance for the outcomes. The effects observed also aligned with the main hypothesis, particularly in terms of generating interest in internships or practical experience terms. When delving into the individual factors of teaching quality, a notable finding is that the aspects of practice, patient contact, theory, and organization hold relatively equal importance. While differences in weighting emerged based on their influence on the attractiveness of traumatology, these distinctions did not achieve statistical significance. Surprisingly, the analysis identified theory as the factor with the greatest influence. This result could either arise from a causal relationship or the possibility that theory was well-explained to many participants, yielding consistently positive ratings. Another plausible explanation is that theoretical explanations by doctors might fall on deaf ears among students with no professional interest. To address the puzzling correlation where students dissatisfied with their teacher’s guidance were more likely to express interest in further specialization in orthopedics and trauma surgery, a closer examination of the exact numbers is warranted. This paradoxical correlation may stem from the small sample size. Subsequent statistical analyses failed to replicate this artificial conclusion. The logistic regression model provided further insights, indicating that skill levels were estimated to increase with students’ interest in traumatology. Therefore, teachers aiming to nurture individual students could focus on more advanced topics for the engaged learners while providing foundational knowledge to others. Overall, the analysis of teaching quality factors supports the thesis that appropriate teaching leads to positive feedback not only within the university setting but also in shaping students’ perceptions of the discipline as a whole.

Furthermore, the question of whether a student is particularly influenced by practical experience, theory, or supportive supervision is highly subjective. Objectively, our analysis revealed that students who neither felt overchallenged nor underchallenged were most likely to remain committed to the field. In our analyses, the ranking of teaching qualities varied depending on the endpoint being considered (influence on the probability of choosing the specialization, acknowledgment of a positive influence from the examination course, or being positively surprised by it). Interestingly, the quality of mentorship emerged as being relatively less influential. This reinforces our argument concerning the lack of significance attributed to frequently changing instructions from various doctors in daily clinical practice. However, it is undoubtedly clear that the importance of effective role models needs to be underscored. Regardless of surgical interest, the aspects of strong mentorship and an open culture of questioning garnered the highest ratings. Research on this topic also highlights the critical role of exemplary role models, aligning with our findings [8,20].

4.6. Limitations

Acknowledging this study’s limitations, it is important to emphasize that this is a simple monocentric sample of one academic year. To avoid bias throughout different years and to achieve homogenous results, we were aiming for a representative analysis of a complete cohort. Additionally, there was no control group in the conventional sense, meaning that no group was surveyed without undergoing the examination course. While such a setup could enhance the result significance, it is precluded by curriculum requirements. The positive aspect is that only a small fraction of students rate the course poorly, yet this does pose challenges for statistical analysis. In actuality, only two students felt that the course negatively affected their perception of trauma surgery. Since we defined our sample size pragmatically, based on the total number of students available, no statistical power calculation was performed. Nevertheless, despite this challenge, the fact that a substantial number of young medical professionals were content with the examination course is encouraging.

A critical remark regarding the statistical interpretation of our data relates to the nature of the Likert scale employed in our questionnaire. While it is mathematically ordinally scaled or “ranked” instead of metric, our questionnaire incorporated a literal assignment of numerical values for participants to mark. For the purposes of logistic regression and univariate analysis utilizing Fisher’s Exact Test, the data was categorized as binomial. This approach effectively mitigated the minor numerical discrepancy associated with the Likert scale’s ordinal nature. The missing validation of the questionnaire was a limitation too, although it was developed strictly based on the existing literature on medical education.

Furthermore, potential bias cannot be entirely ruled out. Lecturers involved in the research course were aware of the survey, eventually leading to more enthusiastic efforts to inspire students. Also, spatial constraints occasionally led to the instructors remaining in the room during questionnaire completion. Finally, it is important to acknowledge that the quality and execution of the examination course could vary due to daily conditions in the clinic. Although the theoretical content remained consistent, different doctors acted as tutors, making it challenging to pinpoint the specific characteristics of positive role models. The interpersonal dynamic and individual affinity may have played a role as well. However, delving into the influence of these diversities is beyond the scope of this study, and the rotation of teaching doctors accurately mirrors the diversity of experiences in university hospitals.

4.7. Future Research and Medical Curriculum

Medical studies in Germany are currently undergoing frequent changes due to curriculum shifts and reforms in entry requirements, emphasizing the necessity for the continuous observation and evaluation of these developments. Osenberg et al. observed in 2008 that students in the so-called model curriculum (a pilot design of medical education in Germany, offered by only a few faculties) became increasingly satisfied with their initially desired subject area as they progressed through their studies [5]. This intriguing finding contrasts with our present findings regarding the current generation in the conventional degree program. We encourage other researchers to compare our results with students currently enrolled in the model curriculum. For the subsequent validation of the results, examining the cohort again at a later stage, such as after completing the final examination, as well as a nationwide comparison with other cohorts, would be advisable. Particularly, investigating the ultimate specialization choices would be valuable in substantiating the results and definitively verifying our hypotheses. It remains imperative to monitor this issue in order to address the doctor shortage in a targeted manner with a subject-centered approach [8].

This decline is further exacerbated by the progressive reduction in time available for teaching, which is constrained by increasing demands on clinical performance and the aforementioned limitations on working hours—not only, but especially in university hospitals. High-quality teaching in trauma and orthopedic surgery is, therefore, crucial to inspire and recruit students into these fields. Enhancing the teaching quality could serve as a vital strategy to counteract the decreasing appeal of these specialties and secure the next generation of trauma surgeons [12]. In March 2019, Yang et al. published a meta-analysis regarding the top twelve influencing factors associated with medical students’ choice of subspecialty; their results are consistent with ours [21]. In addition to longitudinal analyses which will be essential to better understand the long-term impact of surgical education on career decision-making, multicenter studies could provide valuable and diverse perspectives. Although cross-country comparisons may introduce heterogeneity due to differing healthcare systems and educational frameworks, a comparison both on a national and international level would also offer an opportunity to identify universally relevant factors and context-specific challenges in surgical education and recruitment.

In addition, we acknowledge the importance of further validating our questionnaire. Future studies should aim to assess its psychometric properties, including construct validity and test–retest reliability, to ensure that the instrument reliably captures the targeted attitudes and perceptions across various cohorts and settings.

5. Conclusions

The central finding of this study underscores the potential of early engagement with students in fostering a positive affinity towards the discipline of trauma surgery. Even modest-scale events, such as the examination course that initiates the clinical experience, should not be underestimated in their significance. It is more important to consistently nurture students’ interest and entice them with further opportunities for practical involvement. The key lies in teachers embracing their role model status and acknowledging their influence. By doing so, the challenges of securing an adequate number of successors can be mitigated, as heightened commitment can be expected from enthusiastic young practitioners [4]. Consequentially, we suggest considering integrating interest in surgical disciplines in interviews during the application process for medical school. Therefore, surgeons should indeed play an active role in this selection processes for admission. As key stakeholders in clinical education and as role models for aspiring physicians, surgeons are well-positioned to assess candidates’ aptitudes, motivations, and potential for a surgical career. In smaller universities, a one-to-one mentorship program between residents and students should be offered. Curricula should integrate practical experiences at an early stage of education. These recommendations align with the conclusions of other recent publications [22]. Finally, scholarships including the condition to begin a surgical career after graduating could be established.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization M.S.B., R.K. and A.G.; methodology, M.S.B., R.K. and A.G.; investigation, A.G., M.S.B. and L.H.; formal analysis, A.G., M.S.B. and M.V.; software M.S.B. and M.V.; validation M.S.B. and A.G.; resources A.G., M.S.B., A.E. and L.H.; data curation M.S.B. and M.V.; visualization M.S.B., A.G. and M.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G. and M.S.B.; writing—review and editing, M.S.B., R.K., M.V., A.E. and L.H.; supervision, M.S.B. and A.E.; project administration M.S.B. and A.E.; funding acquisition M.S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of University Medicine Greifswald (BB 127/19), September 15 2019. The study was registered with the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS; DRKS00022798) in 22 October 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent, including consent for publication, was obtained from all subjects involved in the study prior to conducting research.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. M.S.B., L.H. and A.E. are employed at BG Hospital Unfallkrankenhaus Berlin gGmbH. This company had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results. R.K. is employed at OrthoCoast. This company had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results. This research received no external funding.

Appendix A

Evaluation of the examination course in traumatology.

Table A1.

Quality of teaching.

Table A1.

Quality of teaching.

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Un-Decided | Agree | Strongly Agree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | The teacher explained the theoretical backgrounds to you in advance. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q2 | The practical relevance was interesting. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q3 | The course focussed on the practical exercises. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q4 | You enjoyed using your knowledge in practice. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q5 | You felt well looked after. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q6 | You have achieved your learning goal. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q7 | The course was well organised and structured. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q8 | You would have appreciated (more) contact to patients. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q9 | You felt encouraged to ask questions. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q10 | You found the level of the course to be appropriate for your skill-level. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q11 | You felt too little challenged. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Table A2.

Previous experience.

Table A2.

Previous experience.

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Un-Decided | Agree | Strongly Agree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | You had positive previous experience in this discipline. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| V2 | You had negative previous experience in this discipline. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| V3 | Your expectations/fears/prejudices regarding the discipline were confirmed. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| V4 | You were pleasantly surprised by the discipline. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| V5 | You were unpleasantly surprised by the discipline. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Table A3.

Expectations of later professional life.

Table A3.

Expectations of later professional life.

| Regarding Your Future Professional Life, the Following Points Are Important to You: | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Un-Decided | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | Work-life balance (regular working hours, compensation for overtime, stress reduction…) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| E2 | Career opportunities | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| E3 | Professional standards | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| E4 | Good working atmosphere | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| E5 | Prestige/image of your specialty | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| E6 | Income above the average | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Table A4.

Desired specialization/location preference.

Table A4.

Desired specialization/location preference.

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Un-Decided | Agree | Strongly Agree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | I already know in which field I would like to specialize further. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| S2 | I can imagine working in a curative field. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| S3 | I would like to work in a surgical department. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| S4 | I am planning to undergo further practical education in the subject of traumatology. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| S5 | I could imagine traumatology as future career. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| S6 | The course had a positive impact on my perception of traumatology. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| S7 | The course had a negative impact on my perception of traumatology. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| S8 | You would most likely want to work in the following specialist discipline later on: (open question) | |||||

| S9 | I prefer the urban space for my residency. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| S10 | I would rate the quality of teaching in big cities better than in rural areas. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| S11 | The rural area offers too few attractive leisure activities. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| S12 | I would like to take on a management position in my professional future. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| S13 | I am attracted by a specialist training in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (area in North Germany). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| S14 | I can only imagine living on the countryside in old age. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| S15 | I would like to set up my own practice later on. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| S16 | The heavy workload in rural areas scares me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| S17 | I think a healthy work-lif balance is more achievable in the countryside than in a city. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| S18 | I definitely want to stay back in my home region. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| S19 | Family and stable friendships are more important to me than my career. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| S20 | I think that a country doctor is less qualified than doctors of the same specialty who practice in a city. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Table A5.

Suggested changes to the examination course.

Table A5.

Suggested changes to the examination course.

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Un-Decided | Agree | Strongly Agree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | I would perceive the examination course in this subject area better in a modified form. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| A2 | Suggestions for optimization: (open question) | |||||

Appendix B

TREND (Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Non-randomized Designs) statement.

Table A6.

TREND (Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Non-randomized Designs) statement. A checklist of items that should be included in reports of non-randomized and quasi-experimental trials. Reported are the page numbers where each of the items listed in this checklist [23].

Table A6.

TREND (Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Non-randomized Designs) statement. A checklist of items that should be included in reports of non-randomized and quasi-experimental trials. Reported are the page numbers where each of the items listed in this checklist [23].

| Topic | Item No. | Recommendations | Reported on Page No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE and ABSTRACT | |||

| Title and Abstract | 1 |

| 1 |

| 1–2 | ||

| 1 | ||

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Background | 2 |

| 2–3 |

| N/A | ||

| METHODS | |||

| Participants | 3 |

| 3 |

| 3 | ||

| 3–4 | ||

| 3–4 | ||

| Interventions | 4 |

| N/A |

| N/A | ||

| N/A | ||

| N/A | ||

| N/A | ||

| N/A | ||

| N/A | ||

| N/A | ||

| N/A | ||

| Objectives | 5 |

| 2 |

| Outcomes | 6 |

| 4 |

| 3–4 | ||

| 3–4; Appendix A | ||

| Sample size | 7 |

| 4–5 |

| Assignment method | 8 |

| N/A |

| N/A | ||

| N/A | ||

| Blinding (masking) | 9 |

| N/A |

| Unit of Analysis | 10 |

| N/A |

| N/A | ||

| Statistical methods | 11 |

| 3–4 |

| 3–4 | ||

| N/A | ||

| 3–4 | ||

| RESULTS | |||

| Participant flow | 12 |

| Appendix C |

| N/A | ||

| N/A | ||

| N/A | ||

| N/A | ||

| N/A | ||

| N/A | ||

| Recruitment | 13 |

| 3 |

| Baseline data | 14 |

| 4 |

| N/A | ||

| N/A | ||

| N/A | ||

| Baseline equivalence | 15 |

| N/A |

| Numbers analyzed | 16 |

| N/A |

| N/A | ||

| Outcomes and estimation | 17 |

| 4–9 |

| 7 | ||

| N/A | ||

| Ancillary analyses | 18 |

| N/A |

| Adverse events | 19 |

| N/A |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Interpretation | 20 |

| 9–12 |

| N/A | ||

| N/A | ||

| 11–12 | ||

| Generalizability | 21 |

| 11–12 |

| Overall evidence | 22 |

| 9–10 |

Appendix C

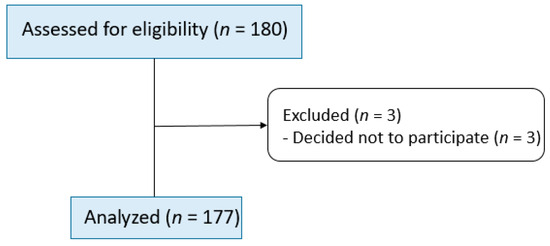

TREND Flow Chart: Description of study population recruitment.

Figure A1.

Flow chart from the TREND (Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Non-randomized Designs) statement: Description of study population recruitment. n = number of participants.

References

- Gibis, B.; Heinz, A.; Jacob, R.; Müller, C. The Career Expectations of Medical Students. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2012, 109, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petzold, T.; Haase, E.; Niethard, F.U.; Schmitt, J. Orthopädisch-unfallchirurgische Versorgung bis 2050. Orthopäde 2016, 45, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt-Sausen, N. Krankenhauskultur: Chefärzte Müssen Umdenken. Deutsches Ärzteblatt. (2020/117(3)). Available online: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/archiv/211891/Krankenhauskultur-Chefaerzte-muessen-umdenken (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Kasch, R.; Engelhardt, M.; Förch, M.; Merk, H.; Walcher, F.; Fröhlich, S. Ärztemangel: Was tun, bevor Generation Y ausbleibt? Ergebnisse einer bundesweiten Befragung. Zentralbl. Chir. 2016, 141, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusche, H.; Huenges, D.O.B.; Klock, M.; Huenges, J.; Weismann, N. Wer Wird Denn Noch Chirurg? |BDC|Online. Der Chirurg BDC. Available online: https://www.bdc.de/wer-wird-denn-noch-chirurg-zukunftsplaene-der-nachwuchsmediziner-an-deutschen-universitaeten/ (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Source: Bundesärztekammer. Ergebnisse Der Ärztestatistik Zum 31.12.2018. Available online: https://www.bundesaerztekammer.de/baek/ueber-uns/aerztestatistik/2018 (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Kasch, R.; Abert, E.; Kolleck, N.; Ghanem, M.; Froehlich, S.; Hofer, A.; Schulz, A.P.; Wassilew, G.; Herbstreit, S. Internship Experience in Orthopaedics and Traumatology and its Impact on Becoming a Specialist. Z. Für Orthopädie Und Unfallchirurgie 2020, 159, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N’cho-Mottoh, M.B.; Coulibaly, I.; Boka, B.; Bamba-Kamagate, D.; Ekou, A.; Aubrege, A. Career choice of ivorian medical students at the end of curriculum: Influencing factors and aspirations. Med. Trop. Sante. Int. 2022, 2, mtsi.v2i1.2022.202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pershad, A.R.; Kidwai, M.S.; Lugo, C.A.; Lee, E.; Tummala, N.; Thakkar, P. Factors Influencing Underrepresented Medical Students’ Career Choice in Surgical Subspecialties. Laryngoscope 2024, 134, 1498–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinh, L.N.; O’Rorke, E.; Mulcahey, M.K. Factors Influencing Female Medical Students’ Decision to Pursue Surgical Specialties: A Systematic Review. J. Surg. Educ. 2021, 78, 836–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, R.H.; Banker, M.B.; Rhodes, R.S.; Biester, T.W.; Lewis, F.R. Graduate Medical Education in Surgery in the United States. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 87, 811–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greiser, J.; Roth, A.; Böcker, W. Universitäre Unfallchirurgie und Orthopädie: Wo geht die Reise hin? Unfallchirurgie 2025, 128, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigg, M.; Arora, M.; Diwan, A.D. Australian medical students and their choice of surgery as a career: A review. ANZ J. Surg. 2014, 84, 653–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, K.A.; Fu, S.; Islam, S.; Larson, S.D.; Mustafa, M.M.; Petroze, R.T.; Taylor, J.A. Medical Student Career Choice: Who Is the Influencer? J. Surg. Res. 2022, 272, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erraji, M.; Kharraji, A.; Abbasi, N.; Najib, A.; Yacoubi, H. Why medical students choose orthopedic surgery as a specialty? Pan Afr. Med. J. 2015, 20, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ihaka, R.; Gentleman, R. R: A Language for Data Analysis and Graphics. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 1996, 5, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Source: Grunddaten der Krankenhäuser 2017, Korrektur der Ausgabe vom 14.09.2018.—Fachserie 12 / 6 / 1 / 1, Tabelle 2.4.3.1 Ärztliches Personal nach funktionaler Stellung, Geschlecht und Gebiets-/Schwerpunktbezeichnung—Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis). 2017. Available online: https://www.statistischebibliothek.de/mir/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/DEHeft_derivate_00041114/2120611177004_Korr01112018.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Source: Unternehmen und Arbeitsstätten. Kostenstruktur bei Arzt- und Zahnarztpraxen sowie Praxen von psychologischen Psychotherapeuten, Fachserie 2 / 1 / 6 / 1, Tabelle 3.2 Arztpraxen (ohne fachübergreifende BAG und MVZ) nach Fachgebiete—Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis). 2015. Available online: https://www.statistischebibliothek.de/mir/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/DEHeft_derivate_00037988/2020161159004_Korr18102018.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Source: Bundesärztekammer. Ergebnisse Der Ärztestatistik Zum 31.12.2023. Available online: https://www.bundesaerztekammer.de/baek/ueber-uns/aerztestatistik/2023 (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Hill, E.J.R.; Bowman, K.A.; Stalmeijer, R.E.; Solomon, Y.; Dornan, T. Can I cut it? Medical students’ perceptions of surgeons and surgical careers. Am. J. Surg. 2014, 208, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, X.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, C.; Lin, H. Factors influencing subspecialty choice among medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e022097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madden, S.; Martin, N.; Clements, J.M.; Kirk, S.J. Factors influencing future career choices of Queen’s University Belfast Medical students. Ulster Med. J. 2023, 92, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Des Jarlais, D.C.; Lyles, C.; Crepaz, N. TREND Group. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: The TREND statement. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).