Abstract

Background: Third molar (M3) removal is considered one of the most frequent oral surgical procedures worldwide. Indications for extraction include both prophylactic and therapeutic reasons. However, this does not come without complications, and despite the widespread practice, there is no consensus on whether prophylactic M3 extraction is more beneficial than conservative management. Aims: The aim of this systematic review is to highlight and compare the main differences and outcomes between prophylactic and therapeutic removal of third molars with conservative treatment and observation. Several factors have been considered such as post-surgical infection risks and complications, hospitalization indications, economic factors and periodontal health of adjacent teeth. Methods: A literature review and meta-analysis were conducted, which comprises studies describing the incidence of postoperative complications, the periodontal status of the second molar (M2), the prevalence of caries, and the economic aspects of the M3 removal. Periodontal parameters of the adjacent teeth such as periodontal pocket depth (PPD) and clinical attachment level (CAL), as well as inferior alveolar nerve (IAN) damage and post-operative inflammatory complications such as bacteremia, were considered. Finally, hospitalization and the economic burden of this procedure were also stated. Results: Third molar retention is associated with increased periodontal disease such as PPD and accumulation of plaque to the adjacent teeth, as well as risk of caries. Contrarily, prophylactic M3 extraction is often linked to unnecessary morbidity and costs, such as risk of bacteremia, trismus, postoperative pain, IAN damage, and sometimes the need for hospitalization. From an economic aspect, this frequent procedure is mostly associated with higher direct and indirect costs, which can exceed the amount of EUR 1000 per patient without hospitalization. Conclusions: This review tried to determine whether the M3 observation and retention can be more beneficial than M3 extraction, after examining certain parameters. Findings indicate that unnecessary morbidity and costs can be attributed to third molar extraction, with postoperative complications such as pain and trismus and sometimes the need for hospitalization. Transient bacteremia also accompanies third molar removal.

1. Introduction

The extraction of third molars (M3s) is considered one of the most commonly performed oral surgery praxes performed worldwide [1,2]. The reasons for removal vary and can be both prophylactic and therapeutic. In a great number of cases, even the eruption of the M3s in the oral environment is a reason for extraction. Moreover, the need to preserve a favorable outcome after an orthodontic treatment to prevent teeth crowding relapse is still a reason for many orthodontists to suggest removal [3,4].

On the other hand, there are many cases where the presence of the M3s is accompanied by symptoms and disease, such as caries and periodontal disease of the adjacent second molar, pericoronitis, pain, abscesses, cervicofacial infection, and others, all of which warrant extraction [5,6,7].

However, as in every surgical procedure, the possibility of adverse effects is visible; nerve damage and paresthesia of the IAN or lingual nerve, post-operative trismus and infection, pain in the TMJ area, fractures of the mandible, bone loss and bacteremia, and post-operative pain-edema-hemorrhage or hematoma are just some of the adverse effects [6,8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

Unfortunately, there is still an absence of clear guidelines in the global literature on whether and in which cases to extract the third molars.

The purpose of this review is to determine whether observation and conservative treatment is more beneficial than therapeutic third molar extraction, when certain parameters are examined. These are (a) the economic aspects—for example, the total cost of the extraction in a private praxis and the days of absence from work; (b) the hospitalization needs; and (c) the post-surgical local infection frequency.

Moreover, this is a systematic review that tries for the first time to summarize all the studies in the literature, with the intent of comparing observation versus third molar extraction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Guidelines Followed

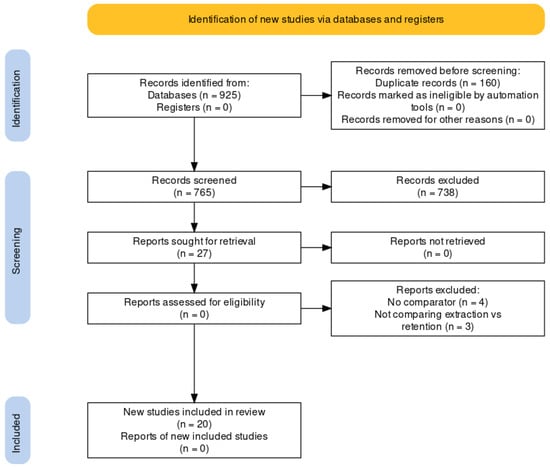

This systematic review adhered to the PRISMA guidelines, which are established standards for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The review protocol was preregistered (PROSPERO CRD42021230603). The flow of the review process is presented in Figure 1 to illustrate the stages of study selection and inclusion.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the inclusion of the eligible articles used in the systematic review according to the PRISMA criteria.

2.2. Search Strategy

Two independent investigators, A.L. and D.T., conducted extensive searches for relevant studies across several electronic databases, including MEDLINE (PubMed), Scopus, and Cochrane (CENTRAL), covering articles published between 1990 and September 2023. Any discrepancies between the two investigators were resolved by a third investigator, T.G. The inclusion of Scopus in the search process was deliberate, as it allowed the inclusion of studies that were not indexed in MEDLINE and CENTRAL, particularly those that may not have been RCTs. In addition to the database search, the review also involved screening conference proceedings and grey literature. The references of studies deemed relevant were also manually reviewed to identify additional studies for inclusion. The search strategy was developed using specific keywords and MeSH terms related to third molar extractions, with a representative example of the search string in PubMed detailed in the manuscript. Supplementary Table S1 contains the full search queries used.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion CRITERIA

The inclusion criteria for studies in this review were also strict (Table S2). Further details about the inclusion criteria and the PICO framework used to guide the review can be found in Supplementary Table S3. Studies reporting patients who had third molar removal for orthodontic or oncological reasons, retrospective studies, and case reports were excluded from this study.

2.4. Data Extraction

Information from each study retrieved from the searches was independently screened on a title and abstract basis by two reviewers (A.L. and D.T.). Following initial screening, a list of eligible studies was independently created by each of the two reviewers (A.L. and D.T.). These lists were forward to M.G. and A.K., who decided upon the final inclusion of each article. Written reasoning was provided in case of exclusion of an already included article. In case of disagreement, a joint consensus by all four authors (A.K.’s vote counted as double in the case of equal votes) determined the final decision. Data from eligible included studies were extracted independently by two reviewers (A.L. and D.T.) using a standardized data extraction form (see below). General characteristics of the study and outcomes for both intervention and control groups were recorded, where available, and double-checked. Efficacy and safety outcomes in the treatment and control groups of individual studies were calculated on an intention-to-treat basis. Any discrepancies during the extraction process were resolved via arbitration by T.G. and A.K.

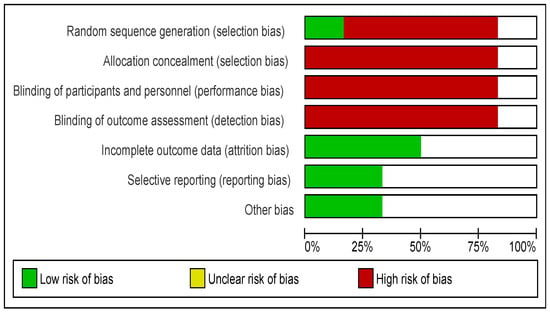

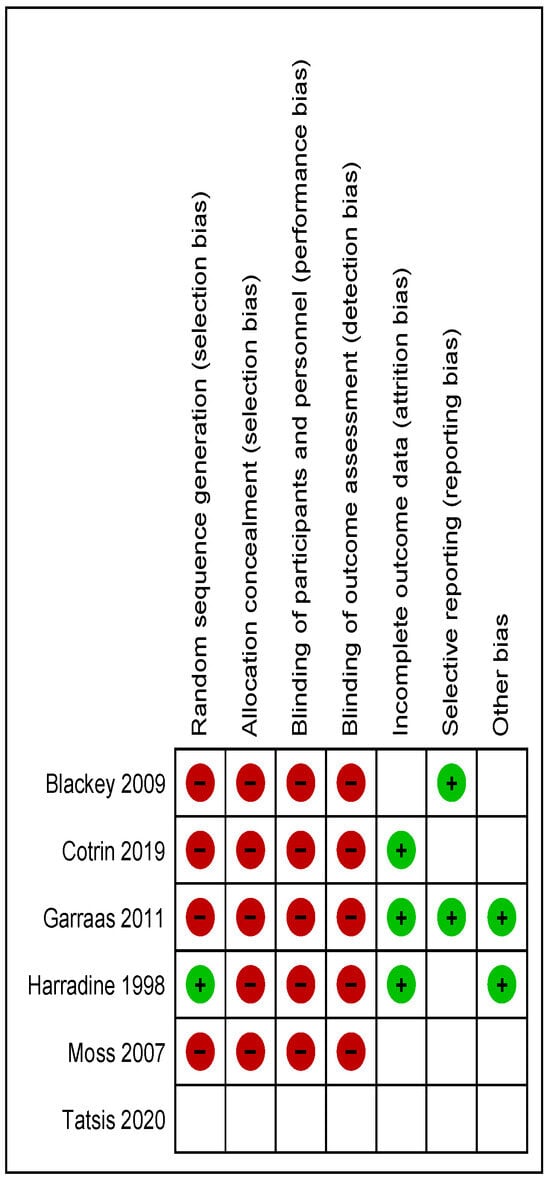

2.5. Risk of Bias and Study Quality Assessment

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the RevMan Risk of Bias tool. Additionally, the potential for publication bias was examined using funnel plots, which are presented in Supplementary Figures (Figures S1 and S2). This step was important to assess the robustness of the findings and to determine whether the results might be influenced by biases in publication.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Relative risks were compared with the Maantel–Haenszel method. Review Manager forest plots and funnel plots are provided. The minimum number of studies to create a new comparison in Review Manager was set to 2. No minimum level of heterogeneity was set, with values lower than 35% considered as low heterogeneity, values ranging from 35% to 65% considered moderate, and values > 65% deemed as considerable heterogeneity. Due to the potential for sensitivity analyses, sensitivity analyses also include forest plots.

Both random and fixed effects models were used, depending on the heterogeneity of the studies. More conservative random effects models were used when heterogeneity was moderate or considerable. The type of study (i.e., RCT, observational, cohort, case–control) was also used as study grouping variables in the sensitivity analyses.

All statistical tests were two-sided, a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and the analysis was conducted with Review Manager v.5.4.1.

3. Electronic Search

Medline (PubMed), EMBASE, and WHO International Clinical Trials Registry databases were used for the search. Articles from 2005 to 2023 related to the comparison between the prophylactic extraction versus the retention and conservative treatment of the M3s were identified. Selected articles were published in journals in English. Full texts of the selected articles were analyzed.

The key words used (Table S1) were: ((third molar) AND (retention) AND (extraction)) AND (study) OR ((third molar) AND (infections)) AND (study) OR ((third molar) AND (bacteremia)) AND (study) OR ((third molar) AND (bleeding)) AND (study) OR ((third molar) AND (periodontitis)) AND (study) OR ((third molar) AND (fracture)) AND (study) OR ((third molar) AND (caries)) AND (study) OR ((third molar) AND (nerve damage)) AND (study) OR ((third molar) AND (paresthesia)) AND (study) OR ((third molar) AND (complications)) AND (study) OR ((third molar) AND (crowding)) AND (study) OR ((third molar) AND (dental arch)) AND (study) OR ((third molar) AND (retention)) AND (study) 20((third molar) AND (cost)) AND (study) OR ((third molar) AND (quality of life)) AND (study).

The types of studies included were controlled clinical trials, cohort studies, case–control studies, and case-series (Table S2). The inclusion criteria for this review included studies with patients of any age and sex who had confirmed existence of third molars, studies that reported follow-up or surgical treatment of those patients, studies with any reported outcome for these patients, RCTs, comparative studies, controlled trials, open label trials, observational studies (cohort, case–control), and case series. As for the exclusion criteria: Studies reporting patients who had third molar removal for orthodontic or oncological reasons, case reports and retrospective studies as well.

4. Results

Description of Results from Literature Search

We identified 925 citations from all searches. After screening the titles and abstracts, we retrieved 765 full texts for further assessment. Of these, 738 were excluded for the following reasons: duplicate publication as conference abstract (n = 160), trial without a control arm, review, retrospective studies, and articles not related to the topic. Twenty-seven full texts were included for descriptive synthesis, among which 20 were included in quantitative synthesis (Figure 1). The Risk of Bias assessment of the studies included in the quantitative syntheses is presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Risk of Bias graph: Review authors’ judgements about each Risk of Bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 3.

Risk of Bias summary: Review authors’ judgements about each Risk of Bias item for each included study.

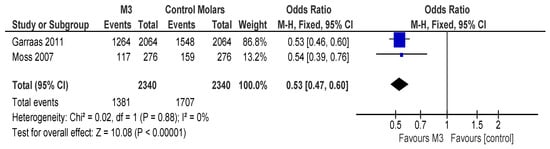

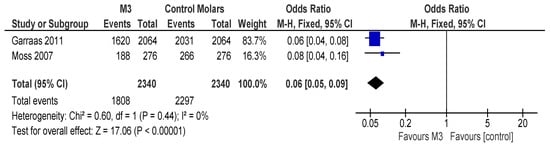

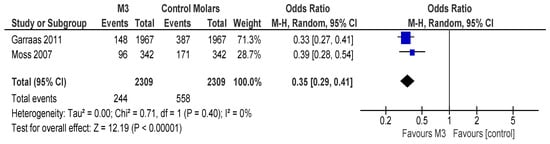

The periodontal status and especially the parameters PPD (pocket depth, Figure 4) and the CAL (clinical attachment level, Figure 5) of the mandibular M2 after the removal of the M3 were studied. It was found that both the PPD and CAL of the M2 were reduced in a five-year follow-up period, especially when partially unerupted M3s were involved [7]. Similar results were also seen in erupted third molars when parameters such as periodontal probing depth (PD) and plaque index (PLQ) were calculated. These were found to be significantly higher in the non-extraction versus the extraction groups, and higher in the maxilla than in the mandible [15]. However, it was seen that the periodontal attachment loss in the distal surface of the M2s had no association with the existence or removal of the M3s [5,6,8,13,15,16,17,18].

Figure 4.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Periodontal/Carries, outcome: 2.1 Percentage of pocket depth > 4 mm (PD4+).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Periodontal/Carries, outcome: 2.2 Percentage of clinical attachment loss > 3 mm (CAL3+).

Another subject that was studied was the periodontopathic bacteria and salivary microbe yeasts before and after the extraction of the M3. According to Rajasuo et al., certain species of gram (-) bacteria, gram (-) rods, and spirochetes were identified in both the M3 and M2 sites, with the total number higher in the M3 area [19]. The observations showed a significant decrease according to those bacteria in the M2 area when the M3 was extracted. Furthermore, salivary mutans streptococci and lactobacilli were highly reduced after the M3 extraction, whereas the candida albicans yeasts were reduced only in the follow-up period.

The relationship between the eruption of the M3s and caries was examined. Distal caries to the second molars that were adjacent to erupted M3s were more likely to occur than in cases where the third molar was absent [6]. Moreover, it was found that there is a connection between the carious M3s and additional caries in teeth more anteriorly to the mouth p < 0.01 [20] (Figure 6). Not statistically important, however, was the existence of caries in the distal surface of the M2s in cases where the M3s had been removed [17].

Figure 6.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Periodontal/Carries, outcome: 2.3 Percentage of Carries.

In many cases, the extraction of a third molar can be a demanding and laborious process that often follows postoperative trismus and pain in the TMJ area. This was found to be up to five times higher in the M3 extraction group than in the non-extraction group [13].

Moreover, another important factor that needs to be considered is the paresthesia and nerve damage of the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN). Specifically, paresthesia occurred almost six times more often after an M3 extraction according to [17], whereas in another study by Valmaseda–Castellón, permanent damage of the IAN after an M3 extraction was more likely to occur than temporary damage (25% versus 1.3%) [21]. A total impaction was associated with a higher risk of IAN injury as well as the close proximity of the mandibular canal to the M3 roots. Other factors highly related to IAN injury were crown sectioning, bone removal, and long-lasting procedures that were also accompanied by excessive bleeding.

Another fact that needs to be considered is bacteremia. According to Tomas et al., bacteremia was present in over 60% of patients after an M3 extraction [11]. A large number of bacteria were found in the blood (131), with streptococcus viridans to be present in almost 90% of the cases.

Surprisingly, the presence of bacteria in blood cultures had no association in all cases, when a number of different parameters were examined. To be more accurate, the presence of bacteria in blood cultures was not statistically significant according to the depth of impaction of the M3, the level of insertion, the relationship to the inferior alveolar nerve and to the ramus-lower M2, and finally to the number of dental roots. Additionally, even when certain oral surgery procedures were used to remove the M3, such as osteotomy and root sectioning, the presence of bacteria in the blood did not change significantly. The time spent completing the extraction was also irrelevant—even when the above procedures were performed—to the elevation of the bacteria in the blood.

The economic aspect (direct and indirect costs) of the M3 removal is another major subject for the patient that has to be considered. “Direct” costs refer clearly to the cost of the surgery, whereas as “indirect” costs are calculated as the cost of transportation, the cost of absence from work due to post-surgical adverse effects, and so forth. According to “Economic Aspects of Mandibular Third Molar Surgery” (2010), the total costs of an M3 extraction may reach the amount of EUR 550/patient, with indirect costs amounting to higher amounts than the cost of the surgery itself. In some cases, this amount exceeded EUR 1000/patient.

On the other hand, each M3 extraction gives rise to possible inflammatory complications. It is also stated that factors such as the degree to which the M3 was impacted and an infection or certain pathology of the M3 that pre-existed the extraction were associated with an increased risk of inflammatory complications following M3 surgery [9,18].

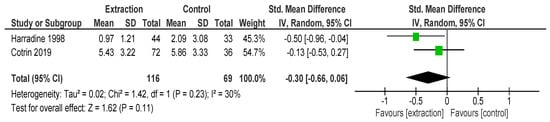

Finally, referring to teeth crowding, in a study by Chou et al., [4] certain parameters were studied, such as Little’s index of irregularity, intercanine width, and arch length. Summarizing currently available evidence, the removal of the M3s as a method to reduce teeth crowding is not statistically important (Figure 7) [3].

Figure 7.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Little Irregularity Index, outcome: 1.1 Mean Change in Little’s Irregularity Index.

5. Discussion

This systematic review was made to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of prophylactic removal of the third molars in contrast with the retention and conservative management of those teeth. It also tries for the first time to summarize all the relative studies in the literature, with the intent of comparing observation versus third molar extraction.

After an extensive literature search, a number of studies between 1990 and September 2023 were identified and used as most relevant to our subject of this review. In total, 20 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and highlighted the main differences between intervention and retention of the third molars.

Several parameters were estimated, such as the periodontal status of the adjacent M2, the presence of caries, the post-operative complications such as paresthesia, trismus, damage of the IAN-lingual nerve, and bacteremia. Finally, the overall cost-effectiveness of this broadly performed oral surgery praxis was considered and studied [17,21,22,23,24]. Inferior alveolar nerve damage is a probable and common complication that may follow the extraction of an impacted M3; in most cases, it is temporary (paresthesia), but in some cases, it may also be permanent. In the study by Mann et al. [17], it was reported that paresthesia of the IAN nerve was found to be six times more probable after an M3 extraction, whereas Valmaseda–Castellón showed that overall permanent damage of the IAN nerve is more frequent than temporary damage (25% versus 1.3%), [21].

Likewise, as reported by Rood and Shehab, in cases where a proximity of the IAN to the impacted M3 is radiographically evident, a temporary inferior alveolar nerve (IAN) paresthesia has a 20–35% chance of occurring, whereas a temporary paralysis occurrence may reach the percentage of 0.9–4% [25]. In such cases, coronectomy of the M3 as an alternative instead of complete extraction has been proposed because of lower IAN disturbance rates, according to Mann and Scott [2]. Only one study (that by Hounsome et al.) reported higher rates of postoperative infection and dry sockets/alveolar osteitis with the coronectomy method, [13].

Lingual nerve damage is also a noticeable complication after an M3 extraction. Risk factors for this could include tooth sectioning, the type of local anesthesia used, and anatomic factors, especially when the lingual nerve is situated closely to the alveolar crest distally to the M2 [23].

According to the findings of this analysis, the total direct and indirect costs of the M3 extraction reached the amount of EUR 550 per person and sometimes exceeded EUR 1000, which is a considerable amount of money regarding such a widely performed oral surgery worldwide. According to the literature, the cost of prophylactic extraction of an impacted M3 was over 30% higher than in cases of retention [26,27]. Additionally, following the watchful–waiting strategy, the total costs of recalls and additional exams performed, such as X-rays, are not considered to be higher than in the case of M3 removal because they comprise routine dental checkups, regardless of the presence of the M3 [26]. Of note in cases of IAN damage, the compensation for the complication has been reported to amount between GBP (Pound sterling) 4000–14,000 or even more [27].

Moreover, the extraction of an M3 may require admittance to the hospital and is performed in several cases under general anesthesia. In those cases, we have to consider both the cost of hospitalization as well as the length of the stay. According to Anjrini, in Australia, the direct cost of each patient who required admittance to the hospital and extraction of the M3 reached the amount of USD 2644, whereas the “watch and wait” alternative was estimated to cost only 1% of the total M3 removal cost of each individual. Thus, no study supported the prophylactic removal of the impacted M3s regarding the economic evidence until now [26,28].

There is no clear benefit of M3 removal with regard to quality of life. Regarding the quality-adjusted life year (QALY), this tends to be lower in the surgical removal scenario than in the retention of the M3s. This reduction in the overall quality of life is specifically due to the complications that often accompany the extraction of an impacted M3, which expectedly outnumber those occurring in the “watch and wait” strategy. The short-term complications and post-extraction pain, swelling, inflammation, chewing ability discomfort, paresthesia, and trismus—which lasts about 4–7 days—strongly affect the quality of life of these patients. On the other hand, it has been reported that, despite the fact that short- or long-term M3 removal complications did have a negative effect on patients’ lives, most of the patients were still pleased by the result in the long term, as they believed that they had improved their health [11,16,17,23,24,26,29,30].

The retention of an impacted M3 is not without periodontal consequences. Factors such as periodontal probing depth (PD) and plaque index (PLQ) were found to be significantly higher in the non-extraction versus the extraction groups, and also higher in the maxilla than in the mandible [7]. Periodontopathic bacteria and salivary microbes were also present in both the M2 and M3 sites, with the total number of them higher in the M2 area. Those microbes (especially streptococci and lactobacilli) were highly reduced after the M3 extraction [16,19].

The presence of caries is also an important matter to be discussed. The presence of caries to the distal surface of the second molars that were adjacent to erupted M3s were more likely to occur in the M3 retention group rather than in those cases where the third molar had been removed [6].

Another matter that is still controversial among orthodontists is the potential crowding relapse of the mandibular incisors owing to the presence of the third molars. However, in our study, in which we studied certain parameters—namely Little’s index of irregularity, intercanine width, and arch length—it was concluded that the removal of the M3s as a method to reduce teeth crowding cannot be statistically justified [4]. Likewise, Cotrin showed that the presence of the M3s and a potential relapse of the mandibular incisors are not related and therefore, the prophylactic removal of the M3s for orthodontic reasons is not indicated [3].

Furthermore, it has been reported that when an adjacent premolar or molar had been extracted for orthodontic reasons, an angulated M3 had greater chances for angulation improvement and upright position eruption in the oral cavity [Richardson ME].

According to Tomás, transient bacteremia is present in almost 60% of the cases after an M3 extraction [11]. A high number of bacteria were found in the bloodstream (131 in total) with streptococcus viridans being the most common pathogen. The number of pathogens in the blood cultures was not associated with the type of procedure that was used to remove the M3, the level of impaction, or the relationship to the IAN nerve.

6. Conclusions

This review sought to determine whether third molar observation is more beneficial than the prophylactic third molar extraction, when certain parameters are examined. From an economic aspect, prophylactic M3 removal is not efficient. Hospitalization is frequently required for M3 removal, which, in the case of prophylactic removal, may contribute to unnecessary morbidity and costs. Another cost is attributable to prophylactic antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory drug needs to prevent sequelae from transient bacteremia, which often accompanies third molar removal.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/surgeries6020037/s1, Figure S1. Funnel plot of comparison: 3 test littles, outcome: 3.1 Mean change. Figure S2. Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Little Irregularity Index, outcome: 1.1 Mean Change in Little’s Irregularity Index. Table S1. Searches. Table S2. Eligible Study designs. Table S3. PICO Framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L. and A.K.; methodology, A.L. and D.T.; software, A.K. and D.T.; validation, T.G., I.T. and A.K.; formal analysis, S.T.; investigation, A.L. and D.T.; resources, A.L. and D.T.; data curation, A.K., T.G. and I.T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.L.; writing—review and editing, A.L., D.T., S.T. and A.K.; visualization, A.K., T.G., S.T. and I.T.; supervision, A.K.; project administration, A.L., A.K. and D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anjrini, A.A.; Kruger, E.; Tennant, M. Cost effectiveness modelling of a “watchful monitoring strategy” for impacted third molars vs prophylactic removal under GA: An Australian perspective. Br. Dent. J. 2015, 219, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avellaneda-Gimeno, V.; Figueiredo, R.; Valmaseda-Castellon, E. Quality of life after upper third molar removal: A prospective longitudinal study. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cirugia Bucal 2017, 22, e759–e766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blakey, G.H.; Parker, D.W.; Hull, D.J.; White, R.P.; Offenbacher, S.; Phillips, C.; Haug, R.H. Impact of Removal of Asymptomatic Third Molars on Periodontal Pathology. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 67, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, Y.; Ho, P.; Ho, K.; Wang, W.; Hu, K. Association between the eruption of the third molar and caries and periodontitis distal to the second molars in elderly patients. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2017, 33, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, S.-K.; Perrott, D.H.; Susarla, S.M.; Dodson, T.B. Risk Factors for Inflammatory Complications Following Third Molar Surgery in Adults. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2008, 66, 2213–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrin, P.; Freitas, K.M.S.; Freitas, M.R.; Valarelli, F.P.; Cançado, R.H.; Janson, G. Evaluation of the influence of mandibular third molars on mandibular anterior crowding relapse. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2020, 78, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedholm, R.; Knutsson, K.; Norlund, A. Economic aspects of mandibular third molar surgery. Br. Dent. J. 2010, 208, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.J.; Ogden, G.R.; Pitts, N.B.; Ogston, S.A.; Ruta, D.A. Actuarial life-table analysis of lower impacted wisdom teeth in general dental practice. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2010, 38, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaas, R.; Moss, K.L.; Fisher, E.L.; Wilson, G.; Offenbacher, S.; Beck, J.D.; White, R.P. Prevalence of visible third molars with caries experience or periodontal pathology in middle-aged and older Americans. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 69, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelesko, S.; Blakey, G.H.; Partrick, M.; Hill, D.L.; White, R.P.; Offenbacher, S.; Phillips, C.; Haug, R.H. Comparison of Periodontal Inflammatory Disease in Young Adults with and Without Pericoronitis Involving Mandibular Third Molars. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 67, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoytrak, B.; Kocaturk, O.; Koparal, M.; Gulsun, B. Assessment of Effect of Submucosal Injection of Dexmedetomidine on Postoperative Symptoms. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 78, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harradine, N.W.; Pearson, M.H.; Toth, B. The effect of extraction of third molars on late lower incisor crowding: A randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Orthod. 1998, 25, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hounsome, J.; Pilkington, G.; Mahon, J.; Boland, A.; Beale, S.; Kotas, E.; Renton, T.; Dickson, R. Prophylactic removal of impacted mandibular third molars: A systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol. Assess. 2020, 24, 1–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worrall, S.; Riden, K.; Haskell, R.; Corrigan, A.M. UK National Third Molar project: The initial report. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1998, 36, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.J.; Cunha-Cruz, J.; Rothen, M.; Spiekerman, C.; Drangsholt, M.; Anderson, L.; Roset, G.A. A prospective study of clinical outcomes related to third molar removal or retention. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leechanavanichpan, P.; Rodanant, P.; Leelarungsun, R.; Wongsirichat, N. Postoperative Pain Perception and Patient’s Satisfaction After Mandibular Third Molar Surgery by Primary Closure with Distal Wedge Surgery. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2019, 11, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, A.; Scott, J. Coronectomy of mandibular third molars: A systematic literature review and case studies. Aust. Dent. J. 2021, 66, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, K.L.; Beck, J.D.; Mauriello, S.M.; Offenbacher, S.; White, R.P. Third Molar Periodontal Pathology and Caries in Senior Adults. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 65, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, M.; Fish, M.D.; Garcia, R.; Kaye, E.; Figueroa, R.; Gohel, A.; Ito, M.; Lee, H.; Williams, D.; Miyamoto, T. Retained Asymptomatic Third Molars and Risk for Second Molar Pathology. J. Dent. Res. 2013, 92, 1095–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passarelli, P.C.; Lopez, M.A.; Desantis, V.; Piccirillo, G.B.; Rella, E.; Giovannini, V.; Speranza, A.; De Leonardis, M.; Manicone, P.F.; Casale, M.; et al. Quality of life of patients with mandibular third molars and mild pericoronitis. A comparison between two different treatments: Extraction or periodontal approach. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petsos, H.; Fleige, J.; Korte, J.; Eickholz, P.; Hoffmann, T.; Borchard, R. Five-Years Periodontal Outcomes of Early Removal of Unerupted Third Molars Referred for Orthodontic Purposes. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 79, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queral-Godoy, E.; Figueiredo, R.; Valmaseda-Castellón, E.; Berini-Aytés, L.; Gay-Escoda, C. Frequency and evolution of lingual nerve lesions following lower third molar extraction. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2006, 64, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasuo, A.; Meurmarr, J.H.; Murtomaa, H. Periodontopathic bacteria and salivary microbes before and after extraction of partly erupted third molars. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 1993, 101, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rood, J.P.; Shehab, B.A.A.N. The radiological prediction of inferior alveolar nerve injury during third molar surgery. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1990, 28, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Wilson, M.P.; Golder, S.; Kleijnen, J. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of prophylactic removal of wisdom teeth Rapid review. In HTA Health Technology Assessment NHS R&D HTA Programme Health Technology Assessment; National Institute for Health and Care Research: Nottingham, UK, 2000; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Tomás, I.; Pereira, F.; Llucián, R.; Poveda, R.; Diz, P.; Bagán, J. Prevalence of bacteraemia following third molar surgery. Oral Dis. 2008, 14, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, A.; Sikora, M. The incidence and extraction causes of third molars among young adults in Poland. Anthr. Rev. 2019, 82, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türköz, Ç.; Ulusoy, Ç. Effect of premolar extraction on mandibular third molar impaction in young adults. Angle Orthod. 2013, 83, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valmaseda-Castellón, E.; Berini-Aytés, L.; Gay-Escoda, C. Inferior alveolar nerve damage after lower third molar surgical extraction: A prospective study of 1117 surgical extractions. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2001, 92, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wijk, A.; Kieffer, J.M.; Lindeboom, J.H. Effect of Third Molar Surgery on Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in the First Postoperative Week Using Dutch Version of Oral Health Impact Profile-14. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 67, 1026–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).