Loss of Independence after Index Hospitalization Following Proximal Femur Fracture

Abstract

1. Introduction

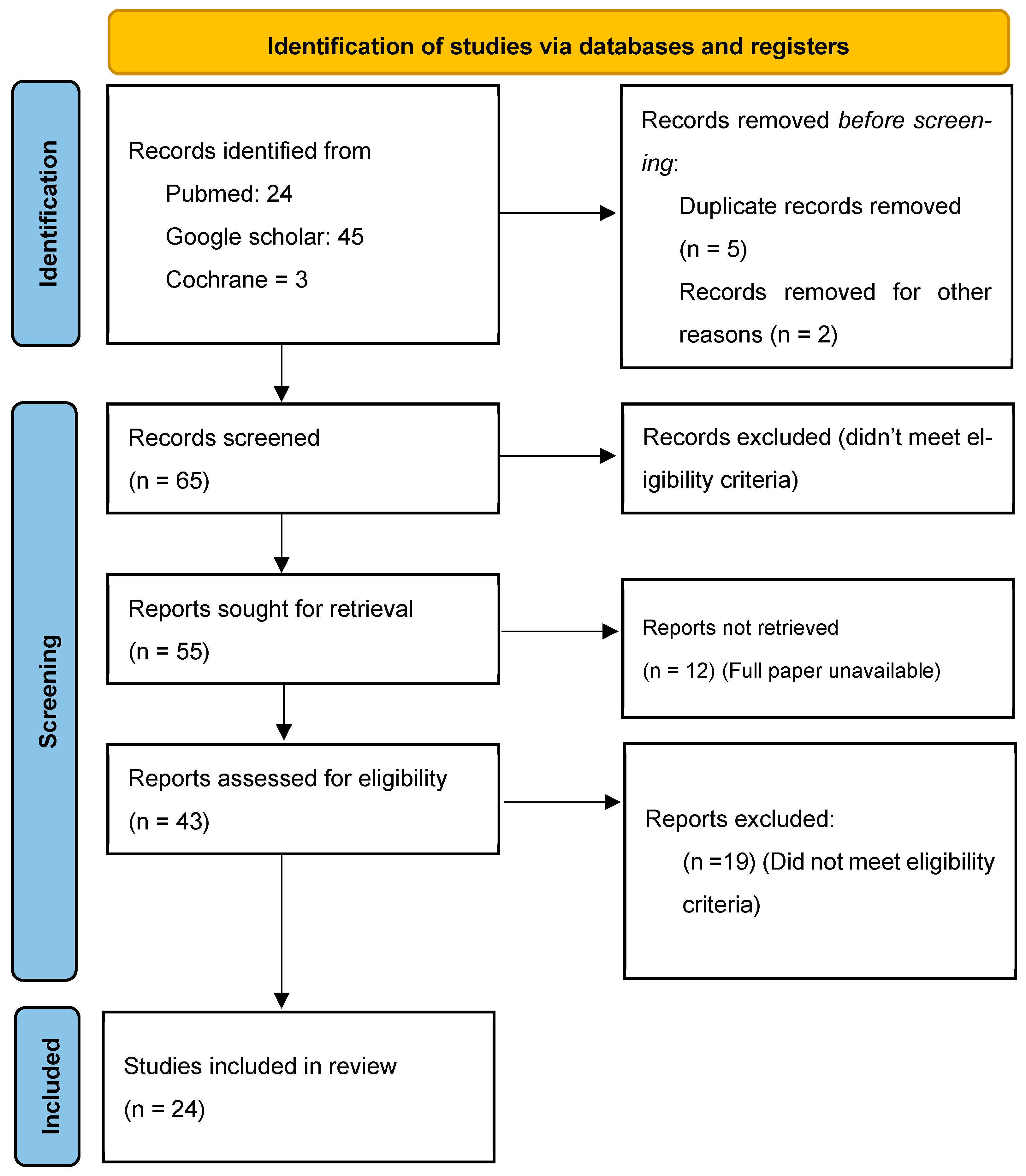

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Prevalence

3.3. Patient Demographics and Risk Factors

3.4. Deposition after Discharge

3.5. Economic Impact

3.6. Social and Psychological Impact

3.7. Loss of Workdays

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Backer, H.C.; Wu, C.H.; Maniglio, M.; Wittekindt, S.; Hardt, S.; Perka, C. Epidemiology of proximal femoral fractures. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 2021, 12, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, N.; Hafner, T.; Pishnamaz, M.; Hildebrand, F.; Kobbe, P. Patient-specific risk factors for adverse outcomes following geriatric proximal femur fractures. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2022, 48, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosquera, M.T.; Maurel, D.L.; Pavon, S.; Arregui, A.; Moreno, C.; Vazquez, J. Incidence and risk factors in fractures of the proximal femur due to osteoporosis. Rev. Panam. Salud. Publica 1998, 3, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mittal, R.; Banerjee, S. Proximal femoral fractures: Principles of management and review of literature. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 2012, 3, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berian, J.R.; Mohanty, S.; Ko, C.Y.; Rosenthal, R.A.; Robinson, T.N. Association of Loss of Independence With Readmission and Death After Discharge in Older Patients After Surgical Procedures. JAMA Surg. 2016, 151, e161689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoicea, N.; Magal, S.; Kim, J.K.; Bai, M.; Rogers, B.; Bergese, S.D. Post-acute Transitional Journey: Caring for Orthopedic Surgery Patients in the United States. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.; Dalton, M.A.; Holmes, J. Large increases in spending on postacute care in Medicare point to the potential for cost savings in these settings. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekegren, C.L.; Edwards, E.R.; de Steiger, R.; Gabbe, B.J. Incidence, Costs and Predictors of Non-Union, Delayed Union and Mal-Union Following Long Bone Fracture. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesser, T.; Kelly, M. Management of Hip Fractures in the Elderly; Elsevier Ltd.: Surgery, UK, 2013; Volume 31, pp. 456–459. [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness, L.A.; Higgins, J.P.T. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res. Synth. Methods 2020, 12, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preferred Reorting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA). Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Van Der Vliet, Q.M.J.; Weaver, M.J.; Heil, K.; McTague, M.F.; Heng, M. Factors for Increased Hospital Stay and Utilization of Post -Acute Care Facilities in Geriatric Orthopaedic Fracture Patients. Arch. Bone Jt Surg. 2021, 9, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Brinson, Z.; Tang, V.L.; Finlayson, E. Postoperative Functional Outcomes in Older Adults. Curr. Surg. Rep. 2016, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugelman, D.N.; Fisher, N.; Konda, S.R.; Egol, K.A. Loss of Ambulatory Independence Following Low-Energy Pelvic Ring Fractures. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 2019, 10, 2151459319878101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keswani, A.; Tasi, M.C.; Fields, A.; Lovy, A.J.; Moucha, C.S.; Bozic, K.J. Discharge Destination After Total Joint Arthroplasty: An Analysis of Postdischarge Outcomes, Placement Risk Factors, and Recent Trends. J. Arthroplasty 2016, 31, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondon, A.J.; Tan, T.L.; Greenky, M.R.; Goswami, K.; Shohat, N.; Phillips, J.L.; Purtill, J.J. Who Goes to Inpatient Rehabilitation or Skilled Nursing Facilities Unexpectedly Following Total Knee Arthroplasty? J. Arthroplasty 2018, 33, 1348–1351.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, F.; Galler, M.; Zellner, M.; Bäuml, C.; Füchtmeier, B. The fate of proximal femoral fractures in the 10th decade of life: An analysis of 117 consecutive patients. Injury 2015, 46, 1983–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.; Carmody, O.; Carey, B.; Harty, J.A.; Reidy, D. The cost and mortality of hip fractures in centenarians. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 186, 961–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, N.; Maggi, S. Epidemiology and social costs of hip fracture. Injury 2018, 49, 1458–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morice, A.; Reina, N.; Gracia, G.; Bonnevialle, P.; Laffosse, J.M.; Wytrykowski, K.; Cavaignac, E.; Bonnevialle, N. Proximal femoral fractures in centenarians. A retrospective analysis of 39 patients. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2017, 103, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavernia, C.J.; D’Apuzzo, M.R.; Hernandez, V.H.; Lee, D.J.; Rossi, M.D. Postdischarge costs in arthroplasty surgery. J. Arthroplasty 2006, 21 (Suppl. 2), 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, D.; Lieberman, D. Rehabilitation after proximal femur fracture surgery in the oldest old. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2002, 83, 1360–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, K.T.; Christianson, E. Expedited Operative Care Of Hip Fractures Results In Significantly Lower Cost Of Treatment. Iowa Orthop. J. 2015, 35, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cameron, I.D.; Lyle, D.M.; Qujnb, S. Epidemiology Health Services Evaluation Branch, N.S.W. Health Department, Locked Bag 961. J. Cttn. Epidemiol. 1994, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda, K.; Amari, T.; Yoshino, K.; Izumiya, H.; Yamaguchi, K. Influence of patients’ walking ability at one-week post-proximal femur fracture surgery on the choice of discharge destination in Japan. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2022, 34, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, A.; Barone, A.; Oliveri, M.; Pizzonia, M.; Razzano, M.; Palummeri, E.; Pioli, G. An Analysis of the Feasibility of Home Rehabilitation Among Elderly People With Proximal Femoral Fractures. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2006, 87, 826–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aigner, R.M.F.T.; Meier Fedeler, T.; Eschbach, D.; Hack, J.; Bliemel, C.; Ruchholtz, S.; Bücking, B. Patient factors associated with increased acute care costs of hip fractures: A detailed analysis of 402 patients. Arch. Osteoporos. 2016, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiihonen, R.; Alaranta, R.; Helkamaa, T.; Nurmi-Lüthje, I.; Kaukonen, J.P.; Lüthje, P. A 10-Year Retrospective Study of 490 Hip Fracture Patients: Reoperations, Direct Medical Costs, and Survival. Scand. J. Surg. 2019, 108, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singaram, S.; Naidoo, M. The physical, psychological and social impact of long bone fractures on adults: A review. Afr. J. Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2019, 11, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohsawa, S.; Miura, A.; Yagyu, M.; Oizumi, A.; Yamada, E. Asserive rehabilitation for intracapsular fracture of the proximal femur. Clin. Rehabil. 2007, 21, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taillandier, J.; Langue, F.; Alemanni, M.; Taillandier-Heriche, E. Mortality and functional outcomes of pelvic insufficiency fractures in older patients. Jt. Bone Spine 2003, 70, 287–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, T.; Thalmann, M.; Jensen, K.O.; Schwarzenberg, P.; Jukema, G.N.; Pape, H.C.; Halvachizadeh, S. Implementation of a novel nursing assessment tool in geriatric trauma patients with proximal femur fractures. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Amling, M.; Oheim, R.; Barvencik, F. A holistic hip fracture approach: Individualized diagnosis and treatment after surgery. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2014, 40, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearl, A.; Crespi, Z.; Ismail, A.; Daher, M.; Hasan, A.; Awad, M.; Maqsood, H.; Saleh, K.J. Hospital Acquired Conditions Following Spinal Surgery: Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Front. Med. Health Res. 2023, 5, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurch, M.A.; Rizzoli, I.R.; Mermillod, B.; Vasey, H.; Michel, J.P.; Bonjour, J.P. A Prospective Study on Socioeconomic Aspects of Fracture of the Proximal Femur. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1996, 11, 1935–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleich, J.; Neuerburg, C.; Schoeneberg, C.; Knobe, M.; Böcker, W.; Rascher, K.; Fleischhacker, E.; Working Committee on Geriatric Trauma Registry of the German Trauma Society (DGU). Time to surgery after proximal femur fracture in geriatric patients depends on hospital size and provided level of care: Analysis of the Registry for Geriatric Trauma (ATR-DGU). Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2023, 49, 1827–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simunovic, N.; Devereaux, P.J.; Bhandari, M. Surgery for hip fractures: Does surgical delay affect outcomes. Indian J. Orthop. 2011, 45, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, N.; Patil, S.; Popalbhat, R. Efficacy of Physiotherapy Rehabilitation for Proximal Femur Fracture. Cureus 2022, 14, e30711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | Article Author Name | Year of Publication | # Patients | Age (SD) | Race | Gender | Disposition to Home | Disposition to Rehabilitation Facility | Length of Stay in the Facility or Hospital | Economic Impact | Mental Status | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Van Der Vliet QMJ, Weaver MJ, Heil K, McTague MF, Heng M. | 2021 | 1074 patients | >65 | N/A | N/A | 168 patients (15.6%) | 878 (81.75%) with 45% being discharged < 20 days. | Median hospital stay = 5 days and Median ICU stay days = 4 days. LOS for rehabilitations = 19 days. (<20 days LOS was found in 398 patients and ≥20 days LOS was found in 392 patients). | N/A | N/A | • Ten percent (n = 108) were re-admitted < 90 days of their discharge. • One year after the injury, 924 patients were still alive. • Higher Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) (p = 0.048), male sex (p < 0.001), pre-injury use of an ambulatory device (p = 0.006) and undergoing surgical treatment (p < 0.001) were associated with longer hospital LOS. • Older age (p < 0.001), pre-injury ambulatory aid (p < 0.001), and pre-existing immobility (p < 0.001) were independent risk factors for LOS > 20 days in a rehabilitation facility. | • Elderly fracture patients utilize a significant amount of post-acute care resources, and age, CCI, surgery, fracture location, pre-injury ambulatory status, and injury living status were found to be associated with the use of these resources. |

| 2 | Kugelman DN, Fisher N, Konda SR, Egol KA. | 2019 | 161 | The average age was 63 years (range: 18–94 years) | N/A | 38 (76%) females, 12 (24%) males. | N/A | N/A | Average LOS in hospital = 6.32 ± 5.7 days. | N/A | N/A | • Fifty patients were available for long-term outcomes (mean: 36 months), as measured by SMFA subgroup scores were demonstrated to be three times higher in patients currently using an assistive device for walking (p = 0.012). • Increased age (p = 0.050) was associated with the continued use of assistive walking devices. • Of the patients who did not use an ambulatory device prior to lateral compression type 1 (LC1) pelvic ring injury, five (11.6%) sustained a fall. Forty-three (86%) patients did not use an assistive ambulatory device prior to sustaining the LC1 fracture. Seven (14%) patients utilized assistive devices both before and after the LC1 injury. | • More than a quarter of the patients sustaining an LC1 pelvic fracture continue to use an aid for ambulation at long-term follow-up. • Older age, complications, and falls within 30 days of this injury are associated with the utilization of an assistive ambulatory device. |

| 3 | Berian JR, Mohanty S, Ko CY, Rosenthal RA, Robinson TN. | 2016 | 9972 | A mean (SD) age of 75 (7) years. | 3876 (76.3%) were white, 563 (11.1%) were black and 639 (12.6%) were other races. | 2736 (53.9%) female | Increased care need was observed in 2339 (46%) patients. A total of >1414 (27.8%) required additional skilled or supportive services at home. | >Out of the care requiring 2339 (46%) patients, 925 (18.2%) required discharge to a non-home destination. | Patients with LOI stayed longer in hospital (mean LOS was 7.3 day) as compared to those without LOI (mean LOS was 3.3 days). | N/A | N/A | • A total of 517 patients required readmission (10.2%). • In a risk-adjusted model, loss of independence was strongly associated with readmission. • Death after discharge occurred in 69 patients (1.4%). • After risk adjustment, LOI was the strongest factor associated with death after discharge (odds ratio, 6.7; 95% CI, 2.4–19.3). | • Loss of independence (LOI) was associated with post-operative readmissions and death after discharge. • Loss of independence can feasibly be collected across multiple hospitals in a national registry. • Clinical initiatives to minimize LOI will be important for improving surgical care for older adults. |

| 4 | Brinson Z, Tang VL, Finlayson E. | 2016 | N/A | ≥60 years | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2–25 days | N/A | N/A | • A randomized control trial showed that the implementation of an inpatient intervention with a focus on the maintenance of the patient’s functional status produced significant improvements in activities of daily living (p < 0.001) and physical performance (p < 0.001) at discharge compared to usual care. • Another study showed that the implementation of a modified Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) intervention that included ambulation or active range-of-motion exercise three times daily resulted in significantly less functional decline at discharge (p < 0.001) in older adults who had had abdominal surgery compared to usual care. | • Post-operative functional status is an important patient-centered outcome. • Living independently is one of the most important aspects in deciding to undergo surgery. • Risk factors for poor functional recovery include baseline frailty, functional disability and cognitive impairment. |

| 5 | Keswani A, Tasi MC, Fields A, Lovy AJ, Moucha CS, Bozic KJ. | 2016 | 106,360 patients | Average age was 64.3 at home, and 71.0 at non-home. (71.6 at SNF, 69.7 at IRF). | Race at home was: Caucasian (72%), Hispanic (2.6%), African Americans (5.4%), Asian (1.7%) and others (18%). Race at non-home destination was: Caucasians (75%), Hispanics (3.9), African Americans (8.7%), Asians (2.3%) and Others (9 | >Home destination, 44% = Male, 56% = females. >Non home setting, 30% = Male, 70% = Female. >In non-home (29% male at SNF and 71% female at SNF 32% male at IRF and 68% females at IRF) | Disposition to home 74,637 (70%). | Discharge to non-home destination was 31,220 (30%) with: skilled nursing facility 19,847 (SNF) (19%), and inpatient rehabilitation facility 11,373 (IRF; 11%). | Length of stay (LOS) tended to be longer in no-home patients (non-home: 3.8 days, home: 3.1 days, p < 0.001) LOS at SNF was 3.6 days and IRF was 3.8 days. | N/A | N/A | • Bivariate analysis revealed that rates of post-discharge adverse events were higher in SNF and IRF patients (all p ≤ 0.001). • In multivariate analysis controlling for patient characteristics, comorbidities, and incidence of complication predischarge, SNF and IRF patients were more likely to have post-discharge severe adverse events. | • SNF or IRF discharge increases the risk of post-discharge adverse events compared to home. • Modifiable risk factors for non-home discharge and post-discharge adverse events should be addressed pre-operatively to improve patient outcomes across discharge settings. |

| 6 | Rondon AJ, Tan TL, Greenky MR, Goswami K, Shohat N, Phillips JL, Purtill JJ. | 2018 | 2281 patients (IRF = 218 and Home = 2063) | • Average age: 73.8 In rehabilitation and 65.7 at home. | Race (non-Caucasian): IRF = 74 (34.9) and Home = 409 (20.2) | Gender (male) IRF = 45 (20.6%) and Home = 880 (42.7%) | 90.4% (2063/2281) of the cohort | • Discharged to post-acute care facilities: 9.6% (218/2281). | LOS: IRF = 3.4 days and Home = 2.0 days | N/A | N/A | • Among 43 variables studied, 6 were found to be significant pre-operative risk factors for discharge disposition other than home. • An age 75 or greater, female, non-Caucasian race, Medicare status, history of depression, and the Charlson Comorbidity Index were predictors for patients going to IRFs. • Any in-hospital complications led to a higher likelihood of being discharged to IRFs and SNFs. • Both models had excellent predictive assessments with area under curve values of 0.79 and 0.80 for pre-operative visit and hospital course. | • Pre-operative and in-hospital factors that predispose patients to non-routine discharges allow surgeons to better predict patient post-operative disposition. |

| 7 | Lavernia CJ, D’Apuzzo MR, Hernandez VH, Lee DJ, Rossi MD. | 2006 | 136 patients | • Average age = 72.5. | Race: White (80.4), Black (6.3%) and others (13.3%). | • Female = 69.9%. | •81.1%. | • Discharge to non-home destination was 31,220 (30%). • Skilled nursing facility 19,847 (SNF) (19%). • Inpatient rehabilitation facility 11,373 (IRF; 11%). | N/A | •Total cost was significantly lower in patients discharged directly to home compared to those who were sent to CRU and subsequently received HC (USD 2405 vs. USD 13,435, p < 0.001) | N/A | • Patients who underwent primary arthroplasty were observed for total cost differences between comprehensive rehabilitation unit (CRU) and homecare (HC). • According to this study, total costs were significantly lower in patients discharged directly to home vs. those who were sent to the CRU and subsequently received HC (USD 2405 vs. USD 13,435 with p < 0.001). • An estimated USD 3.2 billion is spent annually on post-surgical rehabilitation after arthroplasty. | • Post-discharge costs are significantly higher for patients going to a CRU vs. those discharged home, yet both groups had comparable short-term outcomes. |

| 8 | R. Tiihonen1, R. Alaranta1, T. Helkamaa2, I. Nurmi-Lüthje3, J.-P. Kaukonen1, R. Tiihonen, R. Alaranta1, T. Helkamaa, I. Nurmi-Lüthje, J.-P. Kaukonen, P. Lüthje | The Finnish Surgical Society 2018 | 70 of 490 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | • The mean direct costs of primary fracture care were lower than the mean costs of reoperations (EUR 7500 vs. EUR 9800) | N/A | • Reoperations after an operative treatment of hip fracture patients may be associated with higher costs and inferior survival. The costs of reoperations were calculated using the diagnosis-related groups (DRG)-based prices. • In all, 70/490 patients (14.3%) needed reoperations. Of all reoperations, 34.2% were performed during the first month and 72.9% were within 1 year after the primary operation. • Alcohol abuse was associated with a heightened risk of reoperation | • Cost per patient of reoperation in acute care was 31% higher than the corresponding cost of a primary operation. • Reoperations increased the overall immediate costs of index fractures by nearly 20%. One-third of all reoperations were performed during the first month and almost 75% within 1 year after the primary operation. |

| 9 | Andrea Giusti, Antonella Barone, Mauro Oliveri, Monica Pizzonia, Monica Razzano, Ernesto Palummeri, Giulio Pioli, | 2006 | 194 | >70, averaged 83.6 6 years old | N/A | 14.5% male | 99 (49.7%) | • HBR group presented with a slightly better health status, with a lower rate of in-hospital delirium and a lower degree of functional impairment in BADLs and IADLs, and a higher proportion of these patients were living at home with relatives. • 14% (22) need long-term institutionalization after 12 months • Delirium (%) during hospitalization seen in HBR 29 and IBR 45, p value = 0.022. | • In the multiple logistic regression model, the only significant variable affecting the choice of IBR at discharge was the absence of relatives at home (odds ratio [OR], 6.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.33–13.46; p < 0.001), whereas a pre-fracture functional impairment in more than three IADLs (at 12 mo:OR 3.99; 95% CI, 1.57–10.18; p < 0.004), the absence of relatives at home (at 12 mo: OR 8.81; 95% CI, 2.47–31.46; p < 0.001), and delay to surgery longer than 3 days (at 12 mo: OR 5.51; 95% CI, 1.28–23.81; p < 0.022) resulted in significant risk factors for long-term institutionalization. • Those discharged home showed—after controlling for pre-fracture Barthel Index score, IADLs, cognitive status and age—a slightly lower functional decline and a higher rate of recovery during the follow-up (mean change in Barthel Index score standard deviation at 12mo:HBR, 11.2 ± 24.7 vs. IBR, 23. 7 ± 28.5; p value = 0.015). • At 3, 6, and 12 months, the number of surviving subjects was 178, 167, and 158, respectively, and the number of subjects institutionalized was 52 (29%), 26 (16%), and 22 (14%), respectively. • Subjects living alone (%): HBR 23 v/s IBR 62, p value < 0.001. • Mean Barthel Index score ± SD: HBR 85.5 ± 23.4, IBR 82.4 ± 22.6, p value = 0.033. • Mean Katz Index score ± SD: HBR 4.7 ± 1.8, IBR 4.3 ± 1.9, p value = 0.041. • Delirium (%) during hospitalization seen in HBR 29 and IBR 45, p value = 0.022. • The number of patients with complete recovery was higher in the HBR group during the follow-up, even if the differences between the groups were highly significant only at 12 months (52.7% in HBR vs. 32.9% in IBR, p 0.008). • The only factors associated with discharge to the rehabilitation facility were the living situation and the occurrence of delirium during hospital stay. | • In an unselected population of hip-fractured older adults previously living in the community, HBR seems to be a feasible alternative to IBR in those subjects living with relatives. | |||

| 10 | Devora Lieberman, David Lieberman | 2002 | 424 | >75, Mean age ± SD (y) 85+ group 88.8 ± 3.1, 75–84 years group 79.3 ± 2.9, | Israel | Female gender (85+ Group 96 (76), 75–84 Group 233 (79) | Discharged to home: 85+ Group 105 (83), 75–84 group 270 (91), p value = 0.02 | N/A | Days waiting until surgery 85 + group 4.0 ± 2.5, 75–84 group 4.4 ± 3.2, >Days in orthopedic surgery ward after surgery 85 + group 8.0 ± 4.3, 75–84 group 7.1 ± 3.5 >Days hospitalized for rehabilitation 85 + group 22.0 ± 8.2, 75–84 group: 22.0 ± 9.0, | N/A | Discharge FIM (mean ± SD) 85+ Group 74.8 ± 22.1, 75–84 Group 90.5 ± 18.8, p value = 0.0000001 | • Compared with patients aged 75 to 84 years, the older study group was in a worse mental state (p = 0.00005). | • Rehabilitation after surgery for PFF is less successful in an >85 group than in a group of 75-to-84-year-olds. • No differences in terms of duration or the rate of most complications or mortality during the process. |

| 11 | Kyosuke Fukuda, Takashi Amari, Kohei Yoshino, Hikaru Izumiya, Kenichiro Yamaguchi | 2022 | 228((Home group (n = 110), Hospital transfer group (n = 118) | Home group 86.2 ± 6.1, Hospital transfer group 88.0 ± 6.7, p value < 0.05 | Japanese | (female: %) Home group 86 (78.1%), Hospital transfer group 86 (72.8%) | N/A | N/A | • Japan’s long-term care insurance system that allows elderly people to receive appropriate support in their daily lives according to their level of independence and physical and mental functions. • In acute care, a support system called the “community comprehensive care system”, supported by the long-term care insurance system, facilitates community support projects and networks to ensure that elderly people transition smoothly from acute care back into society. | N/A | N/A | • Walking ability before injury (independence: (%) 99 (90.0%) 95 (80.5%), p value < 0.05, Pre-operative waiting days: 2.1 ± 1.9 2.1 ± 1.9. • Post-operative hospitalization days: Home group—40.0 ± 16.6, Hospital transferred group—39.7 ± 17.7. • Walking ability one week after surgery (FAC3 ≤: %): Home group—49 (44.5%), Hospital referred group—34 (28.8%), p value < 0.01. • Barthel Index at discharge: Home group—75.6 ± 22.7, Hospital referred group—58.0 ± 24.6, p value < 0.01. • Odds ratios: walking ability one week after surgery—1.9, p < 0.05, staying with co-residents—4.6, p < 0.01. | • The walking ability after 1 week of surgery and the staying with co-residents or family members significantly increases the rate of home discharge after PFF surgery. |

| 12 | Suguru Ohsawa, Aiko Miura, Mie Yagyu, Anzu Oizumi, Eiji Yamada | 2006 | 20(Assertive method = 13, conventional method = 7) | Age (years) Assertive method = 86.79 ± 4.3, Conventional Method = 87.99 ± 4.1, p value = 0.658 | Japanese | female = 18, p = 0.787 | • The mental state (MMSE) in the assertive group was significantly better than that in the conventional one at the start of rehabilitation in our study (p value = 0.0029). | • All the patients in the assertive rehabilitation group recovered their ability to walk (FIM score) to some extent, while those in the conventional group did not. Ambulation (FIM), Assertive method = 18.29 ± 7.9, Conventional method = 9.49 ± 4.3, p- value = 0.00135. • At 6-month follow-up, the FIM score was significantly higher in the patients treated with assertive rehabilitation (p value = 0.0135), which reflects the gain of independence following surgery by the patients. • However, the mental state (MMSE) in the assertive group was significantly better than that in the conventional one at the start of rehabilitation (p value = 0.0029). | • Assertive conservative therapy is beneficial for gain in ability to walk over conventional treatment after intracapsular fracture of the proximal femur in frail elderly patients who have not had surgery. | ||||

| 13 | J. Moore, O. Carmody, B. Carey, J. A. Harty, D. Reidy | 2017 | 9 | >100 (101 years and 7 months. | Ireland | female = 8, male = 1 | N/A | All patients were discharged to long term care residence | Mean = 14.43 days. | • Average inpatient cost of EUR 14,898. | • This study shows that there is no association with age and longer length of hospital stays in hip fracture patients. • Average inpatient cost of EUR 14,898—this cost is exclusive of component cost, rehabilitation (e.g., physiotherapy, occupational therapy), convalescent care, and outpatient follow-up. • The most recent figures show that the inpatient cost of treating the average hip fracture in Ireland is EUR 12,600, while the inpatient cost of treating hip fractures in centenarians was 18% above that of hip fractures of any age. | • The inpatient 30-day and 1-year mortality rates were 22, 22, and 71%. • Operative management of hip fracture patients over the age of 100 years is associated with an acceptable mortality. rate. | |

| 14 | R. Aigner, T. Meier Fedeler, D. Eschbach, J. Hack, C. Bliemel, S. Ruchholtz, B. Bücking | 2016 | 402 | Age in years 81 ± 8 | N/A | Female 293 (73%) | N/A | N/A | • Length of stay in hospital (in days) 14 ± 6 days. • The length of hospital stay was shorter for patients with an MMSE ≤ 20 (12 vs. 15 days; p < 0.001). | • The mean total acute care costs per patient = EUR 8853 ± 5676 with ward costs (EUR 5828 ± 4294) and costs for surgical treatment (EUR 1972 ± 956) representing the major cost factors. • Pre-fracture Charlson index: 2.4 ± 2.3, • That ward costs accounted for the biggest proportion of total hospitalization costs (EUR 5828 ± 4294 65.8%) | • Cognitive impairment (Mini Mental State Examination < 20) did not have a significant effect on total costs (MMSE ≤ 20 EUR 8248 vs. MMSE > 20 EUR 9176; p = 0.616). | • Only 3% of total costs were spent on physiotherapy EUR 262 ± 224 (3.0%). If physiotherapy can be performed properly, then the total cost could be minimized significantly. • Cost of treatment in males is about EUR 800 higher than for females (p value = 0.128) due to pre-existing premorbid conditions and longer hospital stay. • Charlson comorbidity index: <4: EUR 8353 ± 4616, ≥ 4: EUR 10,383 ± 7939, p value = 0.047, • Cognitively impaired patients were discharged sooner because these patients often did not have the potential for rehabilitation, resulting in shorter lengths of hospital stay. • Cost for pre-existing cognitive impairment (MMSE): MMSE ≤ 20 EUR 8248 ± 3662 and MMSE > 20 EUR 9176 ± 6459, p value = 0.616. | • Thus, individual patients’ specific factor plays a great role in cost of management of fracture. • To reduce the socio-economic burden, fracture prevention programs and cost-effective treatment models are necessary. |

| 15 | Jean Taillandier, Fabrice Langue, Martine Alemanni, Elodie Taillandier-Heriche | 2003 | 60 | 83 ± 7.1 years | N/A | 54 (90%) females, 6 (10%) males | N/A | N/A | Mean length of hospital stay was 45 ± 28 d (range, 10–130 d). | N/A | N/A | • Insufficiency fractures of the pelvis occur in older patients, either spontaneously or after a trivial trauma such as a fall from the standing position. • A total of 52 patients reported a minor fall on the day of admission or within the last few days, while 8 of the fractures were considered spontaneous. • A history of osteoporotic fracture was present in 24 (40%) patients (vertebral fracture, n = 16; femoral neck fracture, n = 10). • A simple fall caused the fracture in 86.6% of patients. • A total of 56 (93%) patients lived at home before the fracture (11 with their spouse or children and 12 with visits from home aides), and the other 4 lived in nursing homes. • A total of 41 (68.3%) were fully self-sufficient before the fracture, 11 used a cane to walk outside their home, and 8 were not self-sufficient. • Complete elimination of weight bearing was required in 52 patients, the mean duration being 12.7 d (range, 3–55 d), whereas 8 patients were able to continue walking, with analgesic treatment. • Length of stay was significantly longer in the patients who were not self-sufficient before the fracture. • Lower degree of self-sufficiency is the reason for institutionalization. • A total of 44 patients returned to their previous place of residence, but 15 were discharged to institutions (11 to nursing homes and four to extended-stay hospitals). • Only 22 patients had the same level of self-sufficiency as before the fracture and 10 experienced a decrease in self-sufficiency. Seven patients (14.3%) died within the year after the fracture. • Only age was significantly associated with loss of self-sufficiency; patients who experienced a marked decrease in self-sufficiency were significantly older than those who recovered their previous level of self-sufficiency (88.2 years vs. 78.5 years; p = 0.0001). • After 1 year, only 36.6% of our patients had the same level of self-sufficiency as before the fracture. • A total of 25% of patients were discharged to institutions. | • Pelvic insufficiency fractures are fairly common in older patients and can raise diagnostic challenges. • Pelvic fractures adversely affected self-sufficiency in this study. |

| 16 | Kyle T. Judd, Eric Christianson | 2015 | 657, (111 = early interventions, 546 = Late interventions) | • Average age for the early intervention group = 79 years. • Average age for the late intervention group = 81 years | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | • The average LOS for the early intervention group was 4.11 days. • Average LOS 5.68 days for the late intervention group (p = 0.0005). | The average cost of the early intervention = USD 49,900 and •The average cost of late intervention = USD 65,300 (p = 0.0086). | N/A | • Due to high costs and an increasing burden of care, there has been interest in newer methods to increase efficiency of care. • One such method is expedited fracture care, with earlier operative intervention. The purpose of this study was to determine if intervention within 6 h of admission decreased costs with no change in the rate of major complications. • Patients were divided into two groups: those undergoing operative intervention < 6 h after admission (early) and those undergoing operative intervention > 6 h after admission. • The average length of stay for the early intervention group was 4.11 days, and it was 5.68 days for the late intervention group (p = 0.0005). • The average cost of the early intervention was USD 49,900, with the average cost of late intervention being USD 65,300 (p = 0.0086). | • Expedited fracture care with earlier operative intervention helps to decrease the cost significantly. The purpose of this study was to determine if intervention within 6 h of admission decreased costs with no change in the rate of major complications. • Programs emphasizing early intervention for hip fractures have the potential for large healthcare savings, with an average saving of USD 15,400. |

| 17 | Ian D Cameron, David M. Lyle, Susan Quine | 1994 | 252 | 84 years | N/A | (83% = female, 17% = male) | N/A | 39% lived in nursing homes prior to sustaining their fracture. | • The mean length of hospital stay was 19.5 days for the accelerated rehabilitation group and • 28.1 days for the conventional care group. | • Total cost was approximately AUD 10,600 for accelerated rehabilitation and AUD 12,800 for conventional care (p value = 0.186) • Because of the reduction in length of stay, the post-surgical component is markedly reduced for the accelerated rehabilitation group (AUD 6420 v/s AUD 8870 (p value = 0.138).) | N/A | • The focus of the analysis in this paper is that of a third-party funding agency (in Australia, the Commonwealth and State Government finance most of the cost of PFFs). • Community services were utilized more frequently by the accelerated rehabilitation group, while the conventional care patients utilized more institutional care. • Physical independence of patients at 4 months after fracture, as measured by the Barthel Index. Accelerated rehabilitation v/s conventional care (50% v/s 41%), which reflects the benefit of accelerated rehabilitation. • The major factor contributing to cost of treatment for PFF in this study was the length of hospital stay. • Accelerated rehabilitation is potentially applicable to most hospitals providing care for patients with proximal femoral fracture. | • This study shows that accelerated rehabilitation is cost-effective in treating PFF and appears superior to conventional orthogeriatric care. • The major factor contributing to cost of treatment for PFF in this study was the length of hospital stay. |

| 18 | Franz Muller, Michael Galler, Michael Zellner, Christian Bauml, Bernd Fuchtmeier | 2015 | 117 (121 fractures) | Patient in 10th decade of life (90–99 years) • Mean age = 92.3 years. | N/A | 81% Female | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | The incidence of dementia was 60% before surgery. • Patient with dementia were referred to nursing home for care. • In revision surgery, 20.5% have dementia who survived (n = 34) | • At the time of follow-up, 83/117 patients (71%) were already deceased. The mortality after 30 days, 6 months, 1 year and 2 years was 16%, 37%, and 43%, and 55%, respectively. • A total of 22 (19%) required revision surgery. • The proximal femoral fractures in the 10th decade of life are associated with high post-operative mortality within the first 6 months. • Surgical revision due to complications did not result in a statistically significant reduction of the survival time. | • The occurrence of proximal femoral fractures in the 10th decade of life results in high post-operative mortality just within the first 6 months. • No explanation regarding cost and limitations of activities or loss of independence. |

| 19 | Till Berk, Marion Thalmann, Kai Oliver Jensen, Peter Schwarzenberg, Gerrolt Nico Jukema, Hans-Christoph Pape, Sascha Halvachizadeh | 2023 | 71 | ≥70 • Mean = 83.54 ± 7.78 | N/A | • Male: 24(33.8%), Female: 47(66.2%) | N/A | N/A | LOS = 14.85 days | N/A | N/A | • Proximal femur fractures (PFFs) are among the most common injuries in the geriatric population; they require hospitalization and surgical treatment. • Mechanism of injury = Low energy impact in 67 (94.4%). • The ePA-AC was assessed on admission by the nursing staff and repeated daily over the course of the inpatient stay. This reflects the condition of the patient from the date of admission to discharge on daily basis; this helps in assessing the patient’s progress. • A total of 49 patients (67.7%) developed at least one complication. • The most common complication was delirium (n = 22, 44.9%). • The group with complications (Group C) had a significantly higher FFI (Fried Fragility Index) compared with the group without complications (Group NC) (1.7 ± 0.5 vs. 1.2 ± 0.4, p = 0.002). • A higher FFI score increased the risk of developing complications (OR 9.8, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.00 to 47.7, p < 0.005). • A higher CDD (confusion, delirium and dementia) score increased the risk of developing delirium (OR 9.3, 95% CI 2.9 to 29.4, p < 0.001). • A higher BS (Braden Score) increased the odds of developing decubitus by 6.2 times (95% CI 1.5 to 25.7, p < 0.001). • Post-operative complications influence the course and outcome following surgery and are associated with increased socioeconomic burden. • The results of this study have shown that the ePA-AC could represent such a multidimensional assessment tool, especially because it seems that the search for an ideal score for the assessment of elderly patients has not yet been achieved. | • The FFI has the highest predictive value for an increased risk of developing complications in general. • CDD is a promising tool for identifying geriatric trauma patients at risk of delirium. • Utilization of the appropriate assessment tool for geriatric trauma patients might support individualized treatment strategies. |

| 20 | Nicola Veronese, Stefania Maggi | 2018 | N/A | N/A | N/A | • Worldwide, hip fractures occurred in 18% of women and 6% of men. • Higher incidence in white women than in men. | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | • Hip fracture is an important and debilitating condition in older people, particularly affecting women. • It is globally estimated that hip fractures will affect around 18% of women and 6% of men (1992 DATA). • The direct costs associated with this condition are enormous since it requires a long period of hospitalization and subsequent rehabilitation. • Cause of hip fracture: decreasing bone mineral density (BMD) and those increasing the rate of fall. • Gender is one of the factors that is influence hip fracture. Higher incidence in white women than in men. • One-third of women in their eighties will have a hip fracture. • Severity: above 80 years—one-third of males die within 1 year after hip fracture as compared to females. • RACE: Whites living at higher latitudes exhibit a higher incidence of hip fractures ranging from 420/100,000 new hip fractures each year in Norway to 195/100,000 in the USA. • Their more recent data (2012) showed that the highest incidence of hip fracture was observed in Denmark (439/100,000), with the lowest in Ecuador (55/100,000). • It is noteworthy that every year about 300,000 subjects are hospitalized for hip fractures in the United States alone. • The estimated cost of treatment in the US was approximately USD 17 billion in 2002. • Worldwide, in women, the lowest annual incidence rate was seen in Nigeria (2/100,000), while the highest was in Northern Europe countries, such as Denmark (574/100,000). • Asians demonstrate an intermediate risk of hip fracture, between white and black individuals [31,32,33], with about 30% of the world’s hip fractures occurring in China, making this a public health concern. • People requiring a long-term care (LTC) facility is estimated between 6 and 60% of people suffering from hip fracture, with costs ranging from USD 19,000 to USD 66,000. • Costs were significantly greater for rehabilitation hospital patients than for nursing home patients | • Hip fracture is a common condition, frequently leading to disability, a higher rate of social isolation, and consequently, mortality. • The global incidence of hip fracture is rising, underlining the need for focusing on its prevention, which is possible through the treatment of osteoporosis and fall risks. |

| 21 | A. Morice, N. Reina, G. Gracia, P. Bonnevialle, J-M. Laffosse, K. Wytrykowski, E. Cavaignac, N. Bonnevialle | 2016 | 39 | >100 years • mean age of 101.3 years (range, 100–108 years) | France | • 33 women and 6 men | • A total of 15 patients living at home at the time of the injury, 3 returned home, 5 entered nursing homes for dependent senior citizens, and 7 were admitted to geriatric rehabilitation units. | A total of 15 patients living at home at the time of injury; 5 entered nursing homes for dependent senior citizens and 7 were admitted to geriatric rehabilitation units Seven patients who were in nursing homes for dependent senior citizens at the time of injury returned to the same institution Of the 14 retirement home patients, 8 returned to their previous institution, 5 entered nursing homes for dependent senior citizens, and 1 was admitted to a geriatric hospital. | Mean hospital stay = 9.5 days [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28] | N/A | • Most patients (61.5%) were institutionalized and many (36%) had dementia | • A total of 15 were living at home and 24 in an institution at the time of the injury (retirement home, n = 16; nursing home for dependent senior citizens, n = 7; or extended-stay hospital, n = 1). • On functional outcomes: of the patients living at home at the time of the injury, 20% returned home after surgery and 15% recovered their previous walking capabilities • A total of 26 patients alive after 3 months had a mean total Parker score decrease of 0.83 ± 0.51 (0–4) and a mean Katz index increase of 0.33 ± 0.18, which signifies the loss of independence of the patients. • After a mean follow-up of 23 ± 14 months (6–60 months), 29 patients had died, including 3 within 48 h, 10 within 3 months, and 15 within 1 year. Complication: confusional state (n = 2). • Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) (range: 2–12) score was 7.46 ± 2.23, with no association to 3-month mortality whether patient is living at home or not (p < 0.08). | • PFFs carry a high risk of death among centenarians. • Mortality is high in centenarians after a PFF. • Multidisciplinary approach is necessary for better outcome. |

| 22 | Nicole Simunovic, PJ Devereaux, Mohit Bhandari | 2011 | >50 years the guideline is applicable | >50 years the guideline is applicable | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | • In Canada, the cost of hip fractures is USD 650 million annually and is expected to rise to USD 2.4 billion based on a projected number of 88,124 hip fracture patients by 2041. • The estimated lifetime cost for all hip fractures in the United States in 1997 likely exceeded USD 20 billion. • In the United Kingdom, direct hospital costs alone were estimated to be USD 125 million in 2003. | N/A | • Hip fractures are associated with a high rate of in hospital mortality of 7–14% and a profound temporary and sometimes permanent impairment of quality of life. • Surgery within <24 h has associations with better functional outcomes and lower rates of perioperative complications and mortality. • Surgical delay increases the rate of pressure ulcers and avascular necrosis. • Early surgery helps in improved ability of patients to return to independence, mobility and pre-fracture living status. • Early surgical correction directly proportional to shorter hospital stay. | • The current evidence for optimal surgical timing is entirely observational and often conflicting for the outcomes of mortality, most post-operative complications, length of hospital stay and return to living status. • The current evidence for optimal surgical timing is entirely observational and often conflicting for the outcomes of mortality, most post-operative complications, length of hospital stay and return to living status. |

| 23 | Nidhi Tiwari, Shubhangi Patil, Rupali Popalbhat | 2022 | 21 years male | 21 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | • A patient’s ability to carry out activities of daily living effectively and efficiently post-surgery is hampered by a variety of obstacles. • Physiotherapy procedures commenced with the purpose of alleviating pain and establishing a normal range of motion. • A significant portion of trauma-related hospitalizations are due to proximal femoral fractures. • To reinstate hip and knee movements to normal, or at the very least to a functional ROM to improve and regain the strength of hip movements, and to restore ROM for hip and knee joints, the patient underwent physiotherapy. • After proper rehabilitation, the patient’s ROM, i.e., both active and passive, was increased at the time of discharge. • After 8 weeks, the ADL (Activity of Daily living assessment was performed with assistive devices. • Muscle strength increased, i.e., pre-treatment v/s post treatment ((1 v/s + 3))-manual muscle testing (MMT). | • Patient’s ROM and muscle strength in the lower limb and face muscles were enhanced with physiotherapy. |

| 24 | Johannes Gleich, Carl Neuerburg, Carsten Schoeneberg, Matthias Knobe, Wolfgang Böcker, Katherine Rascher, Evi Fleischhacker | 2023 | 19712 (data taken from Registry for Geriatric Trauma founded by German Trauma Society. All hospitals certified as Alters TraumaZentrum DGU) | ≥70 years • Median age =85 (IQR 80–89) years. | • A total of 80 hospitals from Germany, Austria and Switzerland were involved) • 19 level I and 61 level II/III trauma center | 72% female | N/A | N/A | • LOS in hospital = 14.1 days of level I and 16 days of level II/III patients with p value = 0.005 | N/A | N/A | • Proximal femur fractures predominantly affect older patients and can mark a drastic turning point in their lives. • Recommended surgical treatment within 24–48 h after admission for better outcome. • When surgery is performed more than 48 h after admission, worse outcome regarding mobilization and mobility as well as significantly increased mortality have been observed • A total of 28.6% of patients were treated in level I, 37.7% in level II, and 33.7% in level III trauma centers. • LOS in hospital was 14.1 days of level I and 16 days of level II/III patients with p value = 0.005 • A total of 38.4% of level I and 32.3% of level II/III patients could walk unaided and nearly 80% of all patients had no existing osteoporosis treatment. • A total of 38.4% of level I and 32.3% of level II/III patients could walk unaided and nearly 80% of all patients had no existing osteoporosis treatment • Mean time to surgery was 19.2 h (9.0–29.8) in level I trauma centers and 16.8 h (6.5–24) in level II/III trauma centers (p < 0.001). • Surgery in the first 24 h after admission was provided for 64.7% of level I and 75.0% of level II/III patients (p < 0.001). • Treatment in hospitals with higher level of care and subsequent increased time to surgery. • Increased odds for worse walking ability 7 days after surgery were found in level I trauma centers. • Mobilization on the first day after surgery was performed significantly more often in level II/III trauma centers. | • Longer time in level I trauma centers compared to level II/III trauma centers, with 64.7% and 75.0% of patients undergoing surgery within 24 h after admission. • Better walking ability 7 days after treatment was observed in hospitals providing lower level of care, which also showed shorter time to surgery. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maqsood, H.A.; Pearl, A.; Shahait, A.; Shahid, B.; Parajuli, S.; Kumar, H.; Saleh, K.J. Loss of Independence after Index Hospitalization Following Proximal Femur Fracture. Surgeries 2024, 5, 577-608. https://doi.org/10.3390/surgeries5030047

Maqsood HA, Pearl A, Shahait A, Shahid B, Parajuli S, Kumar H, Saleh KJ. Loss of Independence after Index Hospitalization Following Proximal Femur Fracture. Surgeries. 2024; 5(3):577-608. https://doi.org/10.3390/surgeries5030047

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaqsood, Hannan A, Adam Pearl, Awni Shahait, Basmah Shahid, Santosh Parajuli, Harendra Kumar, and Khaled J. Saleh. 2024. "Loss of Independence after Index Hospitalization Following Proximal Femur Fracture" Surgeries 5, no. 3: 577-608. https://doi.org/10.3390/surgeries5030047

APA StyleMaqsood, H. A., Pearl, A., Shahait, A., Shahid, B., Parajuli, S., Kumar, H., & Saleh, K. J. (2024). Loss of Independence after Index Hospitalization Following Proximal Femur Fracture. Surgeries, 5(3), 577-608. https://doi.org/10.3390/surgeries5030047