1. Introduction

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are recognized to be the most common bacterial infections in children and the cause of fever in 4.1–7.5% of children accessing a pediatric clinic [

1]. Their incidence varies depending on age and sex: for boys, it is highest during the first 6 months of life (5.3%) and decreases to 2% for the ages of 0–6 years, while in girls, UTIs are less common during the first 6 months of life (2%) and increase in incidence to around 11% for the ages of 0–6 years [

1,

2].

UTIs’ leading causative microorganism is

E. coli, although other bacteria are rising in prevalence.

Klebsiella pneumoniae,

Enterobacter spp.,

Enterococcus spp.,

Pseudomonas spp.,

Proteus spp. and the fungus

Candida spp. are more frequent in nosocomial UTIs than in community-acquired infections, even though their prevalence is increasing in the community setting [

3].

Both children with normal urinary tracts and children with anatomic abnormalities can develop UTIs, although they are more prevalent in the latter. The typical UTI symptoms may vary according to the child’s age, but they all share the risk of serious long-term consequences, like renal scarring. According to the European Association of Urology (EAU) Guidelines on Pediatric Urology, associated risk factors for recurrent UTIs include bladder and bowel dysfunction (BBD), vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) and obesity: in combination with delayed treatment, they ease renal scarring. Each new febrile UTI in a child increases the risk of renal scarring by 2.8%, 25.7% after the second infection and up to 28.6% after three or more febrile UTIs [

4]. Therefore, it is important to prevent UTIs in children, especially if recurrent.

While low-dose antibiotic prophylaxis has been the mainstay for UTIs prevention for a long time, recent evidence raised concerns about antimicrobial resistance, efficacy and safety of antibiotics, thus highlighting the necessity to focus on non-antibiotic preventive interventions. The current recommended non-antibiotic measures to treat and prevent UTIs include dietary supplements such as cranberry, probiotics and vitamins A and E. Meena et al. [

5], evaluating 1426 participants, analyzed cranberry-based products and probiotics: cranberry was as effective as antibiotic prophylaxis and better than placebo/no therapy in reducing UTIs recurrence; probiotics were more effective than placebo and no better than antibiotic prophylaxis, reducing the risk of antibiotic resistance.

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is a precursor of the antioxidant tripeptide glutathione (GSH) and a synthetic derivative of the endogenous amino acid L-cysteine. It modulates several pathophysiologic processes such as oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, apoptosis and inflammation. Oxidative stress plays an important role in inflammation; thus, the antioxidant effects of NAC confer anti-inflammatory benefits [

6]. NAC also appears to modulate inflammation through other mechanisms, including inhibition of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB; a protein complex involved in inflammation) and pro-inflammatory cytokines [

1].

The NAC therapeutic activity, as described by Raghu et al., has been analyzed for more than 50 years so far [

7]: its clinical benefits as a mucolytic and mucoregulator agent were first described in patients with cystic fibrosis in the 1960s and, in the 1970s, NAC was first used to treat paracetamol overdose, thanks to its prompt ability to replace intracellular GSH, thus avoiding acute hepatotoxicity. NAC has a clearly established safety record and it is already considered a therapeutic option for conditions with abnormal, thick or sticky mucus secretions such as pneumonia, bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cystic fibrosis (CF) and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). It also has a powerful anti-inflammatory effect in endotoxemia, reducing tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukins (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8) production, suppressing the activity of NF-κB and enhancing oxygen extraction in kidney and gastrointestinal diseases, psychiatric illnesses and neurodegenerative conditions [

7,

8,

9]. As demonstrated by Dinicola et al. [

10], NAC has a fundamental role as an adjuvant molecule in treating bacterial biofilms, with an excellent efficacy and safety profile. Therefore, combined with several antibiotics, NAC has demonstrated to promote their permeability to the biofilm’s deepest layers, overcoming the resistance to the classic antibacterial approach.

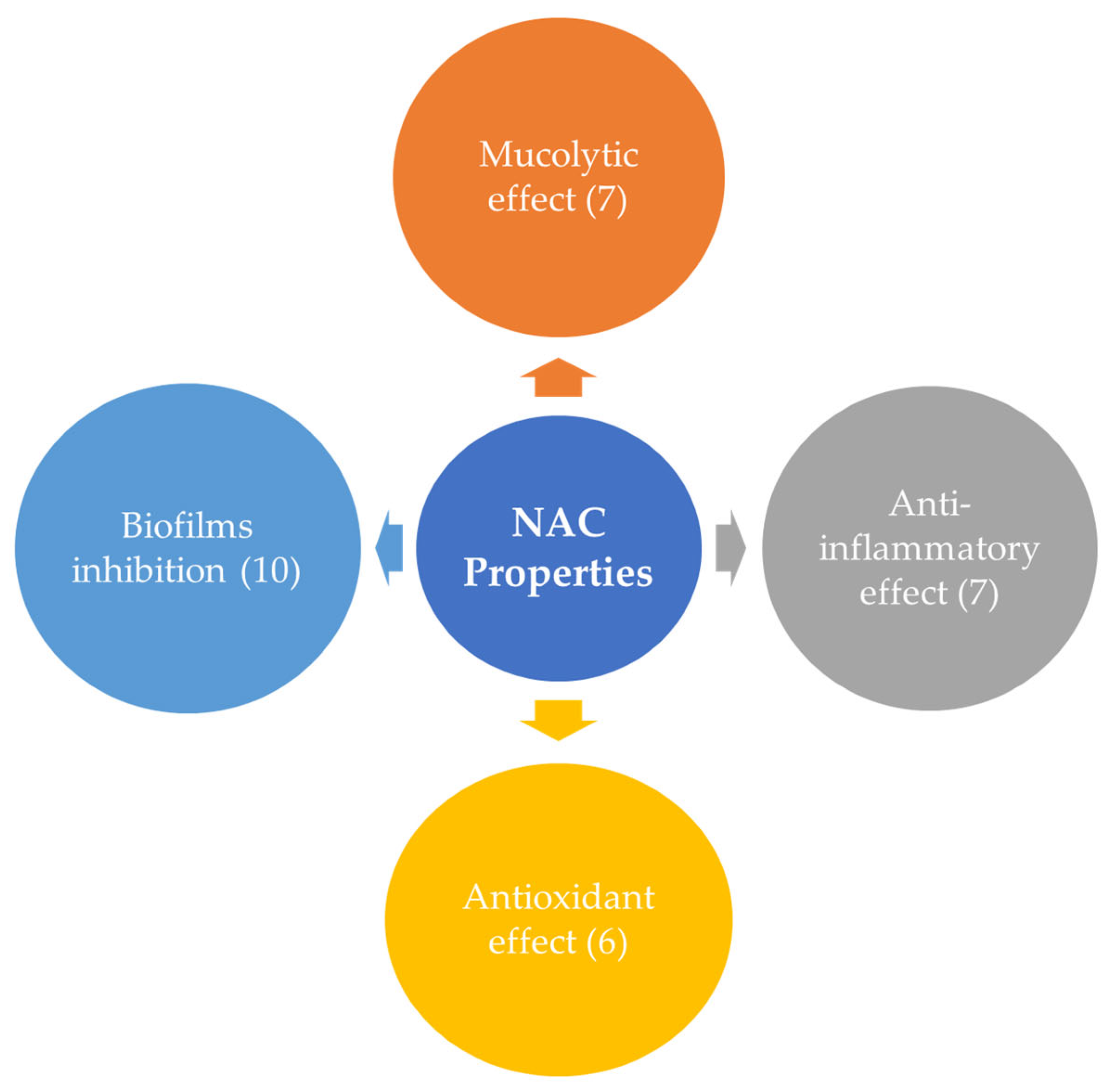

NAC’s main properties are summarized in

Figure 1.

In this work, we aim to discuss the current applications of NAC in adult urology and its future possible evolutions in the pediatric urology field.

2. NAC in Urology: Preclinical Evidence

On a preclinical level, NAC has already been shown to have a pivotal role in preventing cell invasion and biofilm formation caused by urinary tract bacterial pathogens, as demonstrated by Manoharan et al. [

11]. In this study performed in vitro, NAC was demonstrated to completely inhibit the invasion of bladder epithelial cells by multiple

E. coli and

E. faecalis clinical strains, in a dose-dependent manner, without displaying any cytotoxicity against bladder epithelial cells despite its intrinsic acidity. NAC also prevented biofilm formation in combination with ciprofloxacin, reducing bacterial loads and damaging bacterial membranes.

NAC has even been demonstrated to prevent catheter occlusion and inflammation in catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CA-UTIs) in vitro, through its activity of urease activity suppression at low concentrations. The study performed by Manoharan et al. [

12] showed that NAC has bacteriostatic activity against

Proteus mirabilis, a key pathogen in CA-UTIs able to form crystalline biofilms that occlude catheters. NAC inhibits biofilm formation and thus also catheter occlusion. It acts in several stages of biofilm formation, including the initial adhesion to disruption of mature biofilms when combined with ciprofloxacin. Additionally, NAC targets urease, a factor that can enhance intrinsic resistance, and limits inflammatory mediated damage to bladder epithelial cells: thus, it represents a powerful approach to combat antibiotic resistance and can facilitate improved outcomes with antibiotic therapy. Biofilms in NAC-treated catheters presented a calcium, magnesium and phosphate depletion and an increased Michaelis–Menten constant (Km), confirming the absence of any urease activity. The NAC activity against anti-urease/crystal formation, together with its antibiofilm action, significantly improves its potential use in preventing catheter incrustation: biofilm disruption and eradication are the main goals in the context of CA-UTIs. NAC also subdues the inflammatory response of bladder epithelial cells to infection and does not induce the production of IL-6, IL-8 and IL-1b, thus providing evidence of its safety as a UTI treatment.

In addition, the case–control study performed by El-Feky et al. [

13] shows that NAC, combined with ciprofloxacin, has an effect on bacterial adherence and biofilm formation also on ureteral stent surfaces. The study examined 12 biofilm-producing strains isolated from urine samples and stent segments collected from patients undergoing ureteral stent removal. NAC was studied in two concentrations: 2 mg/mL and 4 mg/mL. It showed a statistically significant inhibitory effect on the production of biofilm, which was specifically ≥60% at a concentration of 2 mg/mL and ≥76.6% at 4 mg/mL. Additionally, the ciprofloxacin/NAC combination showed the highest inhibitory effect on biofilm production (94–100%) and the highest pre-formed biofilm disruption (86–100%) compared to controls. This study demonstrated that NAC increases ciprofloxacin therapeutic efficacy by degrading the biofilm’s extracellular polysaccharide matrix. These results were statistically significant and the inhibitory effects of ciprofloxacin and NAC on biofilm production were also verified by scanning electron microscope (SEM).

Finally, the study performed in vitro by Schrier et al. shows that NAC could be employed also in the neobladders context: it decreases the viscosity of ileal neobladder mucus [

14]. Thus, facilitating mucus evacuation can also impact neo-urinary tract microbiota modulation [

15], improving epithelium stability and inhibiting biofilm formation.

3. Current NAC Applications in Adult UTIs

NAC is gaining relevance in urology thanks to its mucolytic and mucoregulator activity.

Extensive research has demonstrated that biofilms, primarily formed by microorganisms, cause approximately 65% of nosocomial infections, 80% of chronic infections and 60% of all human bacterial infections [

16]. In recent years, the utilization of ureteral stents has seen a notable increase in urological practice: these stents’ presence contributes to the formation of biofilms, thus facilitating the development of infections. As the use of stents continues to rise, so does the complicated UTI incidence. Infections related to catheters and urinary stents may lead to bacteremia, acute pyelonephritis and renal failure. Consequently, preventing bacterial adherence to stents, indwelling catheters or host cells may reduce the biofilm-associated infections incidence. Concerning this aspect, AbdelRazek et al. [

17] performed a prospective randomized study on 636 participants who underwent double-J (JJ) ureteral stent insertion after several urological procedures. The participants were randomized into four groups: A (n = 165) for no antibiotics or mucolytics during stent indwelling; B (n = 153) for oral NAC (200 mg/day for children aged < 12 years old and 600 mg/day for adults) during stent indwelling; C (n = 162) for oral co-trimoxazole (2 mg TMP/kg/day) during stent indwelling; and D (n = 156) for both oral NAC and co-trimoxazole during stent indwelling. Urinalysis was performed on all the participants two weeks after the JJ insertion and urine culture was conducted on a stent segment on the day of JJ removal. Positive stent cultures were found in 63.6%, 43.1%, 37% and 19.2% of patients of groups A, B, C and D, respectively. In the stent culture of all groups,

E. coli was the most commonly isolated microorganism. NAC and co-trimoxazole in combination were more effective than either alone: they showed a synergistic effect that enhanced their effectiveness against bacterial infections, thus reducing bacterial adherence and biofilm formation.

Additionally, NAC can offer therapeutic applications even in patients submitted to urological mini-invasive diagnostic procedures: the study by Palleschi et al. [

18], performed in the clinical model of the urodynamic investigation, compared the administration of an association of NAC and D-mannose versus antibiotic therapy in the prophylaxis of UTIs potentially associated to urological mini-invasive diagnostic procedures. A total of 80 patients were prospectively enrolled and randomized into two groups, A and B. Participants of group A underwent an antibiotic therapy based on 400 mg/day of Prulifloxacine, taken by mouth, for 5 days, while participants of group B followed the association of D-mannose and NAC, with two vials/day administered for 7 days. All the participants were submitted to urine examination and urine culture ten days after the urodynamic study. The follow-up assessment did not highlight any statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding UTI incidence. Thus, the association of NAC and mannose showed similar results to antibiotic therapy in preventing UTIs in patients submitted to urodynamic examination.

NAC has even been analyzed by Marchiori and Zanello [

19], in association with D-mannose and

Morinda citrifolia fruit extract (association identified with the acronym NDM), to treat recurrent cystitis in women who survived breast cancer. Breast cancer survivors in adjuvant therapy often experience an estrogen deficiency, with a consequent loss of urothelial trophism, which leads to genitourinary syndrome and dysendocrine cystopathy. These conditions are accompanied by atrophy of the urological mucosa and are characterized by atrophic vaginitis, dyspareunia and urinary disorders such as urgency, frequency, incontinence and recurrent UTIs, mainly bacterial cystitis. Bladder-colonizing bacteria are mainly

Enterobacteriaceae (

E. coli,

Klebsiella pneumoniae,

Shigella,

Pseudomonas spp.). This study retrospectively analyzed 60 women who survived breast cancer with recurrent cystitis, divided into two groups: group 1 was composed of participants treated with antibiotic therapy and NDM for six months, while participants in group 2 were treated only with antibiotics. Subjects of group 1 showed a significantly major reduction in positive urine cultures and an improvement in urgency, frequency, urge incontinence, recurrent cystitis, bladder and urethral pain. This work demonstrated that NAC, in association with D-mannose and

Morinda citrifolia fruit extract, improves antibiotic therapy effectiveness in fighting the pathogenic effect and the resistance of uropathogenic bacteria. The observed therapeutic efficacy was associated with a reduction in UTIs and urogenital discomfort, which highly impact the quality of life of women with long life expectancy.

All of the mentioned evidence about NAC in adult urology is summarized in

Table 1, while

Figure 2 resumes the current NAC applications in treating and preventing UTIs in adult patients.

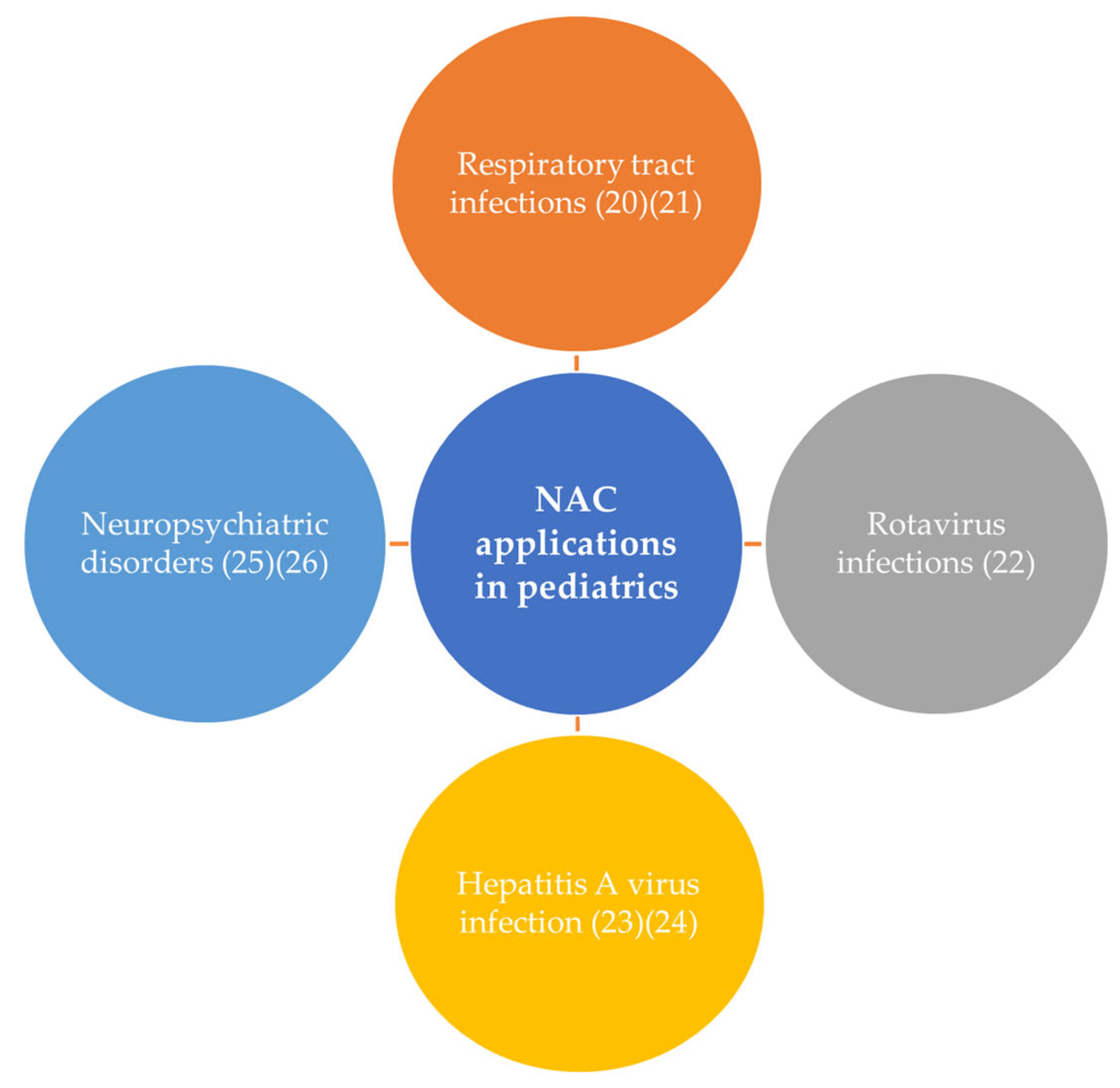

4. Current NAC Applications in Pediatrics

NAC is already used as a therapeutic and prophylaxis option in the pediatric field, showing an excellent tolerability profile. Its principal applications in pediatrics are illustrated in

Figure 3.

It is recognized as a valuable mucolytic option [

20] in children with upper and lower respiratory tract infections [

21], showing a pronounced mucolytic effect without an excessive increase in sputum volume. As demonstrated in adult patients, even in children it destroys bacterial biofilms and prevents their formation.

The study performed by Guerrero et al. [

22] shows that NAC represents an efficient treatment strategy in rotavirus-affected children if administered after the first diarrheal episode. It leads to a decreased number of diarrheal episodes, excretion of fetal rotavirus antigen and symptoms resolution after 2 days of treatment. Therefore, it prevents the severe accompanying of life-threatening dehydration.

NAC has already been recognized as hepatoprotective in children infected by hepatitis A virus [

23], as it significantly and safely reduces liver enzymes. The study performed by Sotelo et al. [

24] also showed that NAC is an effective therapy for hepatitis-A-induced liver failure, giving the clinical course a favorable end and preventing the fatal outcome of hepatic encephalopathy. The study participants showed good tolerance to the treatment.

NAC represents a consolidated therapeutic option, even in different contexts, such as in several pediatric neuropsychiatric disorders, including obsessive–compulsive [

25] and autism spectrum disorders [

26]. NAC results safe and tolerable, reducing irritability and hyperactivity and enhancing social awareness in children with autism spectrum disorders, although its administration does not represent a general recommendation yet [

26].

Currently, although its safety and tolerability in children have been extensively demonstrated, NAC has never been officially standardized as a therapeutic and prophylaxis option in pediatric urology daily practice.

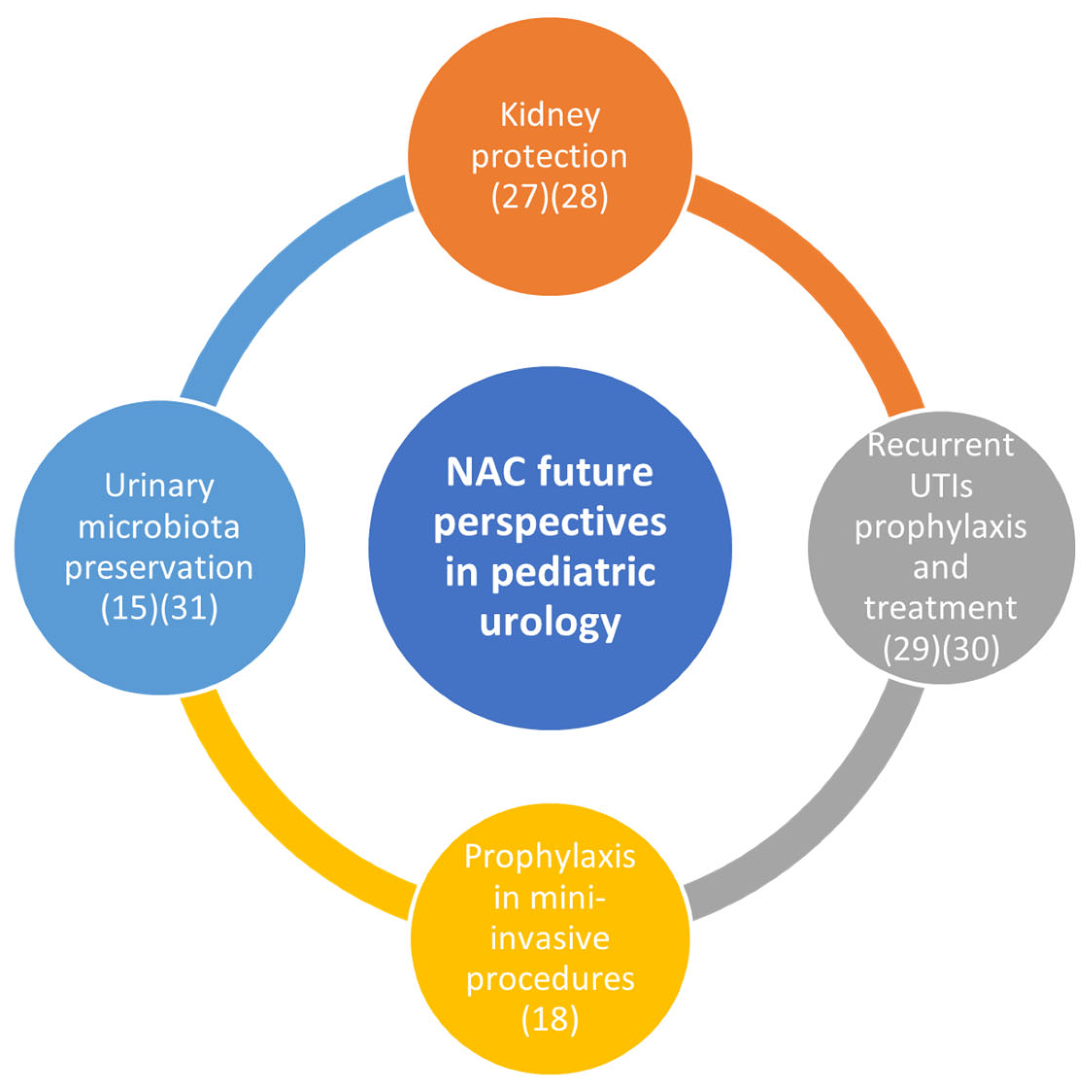

5. NAC Future Perspectives in Pediatric Urology

NAC is revealing interesting properties that will probably influence our future clinical practice, as shown in

Figure 4.

The study performed on rats by Massola Shimizu et al. [

27] demonstrated that NAC has a protective activity against renal injury following bilateral ureteral obstruction: its administration provided significant protection against post-bilateral ureteral obstruction glomerular filtration rate (GFR) drops and reductions of renal blood flow (RBF). Urine osmolality was significantly lower in rats with bilateral ureteral obstruction than in a sham-operated group or NAC-treated rats, the latter also presenting a lower level of interstitial fibrosis. This study demonstrates that NAC administration improves renal function impairment observed 48 h after the relief of 24 h bilateral ureteral obstruction.

Additionally, the three-year cohort study performed by Chiu et al. showed that NAC, administered for two to three years, can reduce the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) modulating the serum creatinine (SCr) and eGFR level [

28].

Manoharan et al. demonstrated that NAC provides a potentially novel and efficacious UTI treatment. This could be applied in particular to recurrent cystitis in girls and young adolescents from the first instance of sexual intercourse since this can lead to an early resistance to common antibiotics [

29].

The results observed by Palleschi et al. about NAC application in the urodynamic investigation in adult patients [

18] could also be applied to pediatric urology: the currently recommended prophylaxis of pediatric urodynamic procedures and cystographies only includes antibiotics, although an alternative option based on NAC could avoid antibiotic resistance, as well as side effects (e.g., bowel dysbiosis, allergies).

Additionally, the review by Crocetto et al. [

30] demonstrated that NAC, enhancing the activity of the mucosal lining, could potentially reduce the adhesion of bacteria to the whole urinary tract epithelium: this could prevent the attachment and colonization of uropathogenic bacteria, reducing the likelihood of recurrent UTIs. These results, applied to pediatric urology, could represent a turning point in the treatment of UTIs in children.

Finally, thanks to its potentially important role in reducing the antibiotics administration, NAC could also contribute to preserving the homeostasis of the urinary microbiota (UM), composed of more than 100 bacterial species from more than 50 genera and with different composition among adults and prepuberal children [

15]. As demonstrated in the review performed by Lemberger et al. [

31], urinary microbiota destruction in children could result in life-long dysbiosis. Therefore, it is even more crucial to implement the use of non-antibiotic approaches, such as NAC, to treat and prevent UTIs.

6. NAC: Advantages, Limits and Potential Issues in Applicability

The hypothesized daily use of NAC in clinical settings is not bereft of limits and expected operative difficulties.

Firstly, although NAC prospects a considerable amount of positive results from a theoretical point of view, very rigorous studies are required to demonstrate the clinical effectiveness of NAC in treating and preventing infections. In other terms, the NAC properties in preventing or exerting a synergic effect with antibiotics in treating infections must be proved in each peculiar clinical setting. For example, we need to state its superiority in treating acute infections when associated with antibiotics rather than antibiotics alone, as well as its absolute role in prophylaxis during invasive exams such as cystography or urodynamics. This needs very well-designed pivotal case–control studies that, in a second phase, could demonstrate the role of NAC alone. Therefore, conscious and substantial investments would be needed.

On the other hand, implementing NAC use in our clinical practice could present several positive aspects (

Figure 5). Firstly, NAC use is already consolidated in clinical practice, even in the pediatric setting. Its prospected application in pediatric urology would only require a different indication, in order to be extensively used in pediatric urology. Additionally, NAC is easy to find, with simple formulations that do not require an administration performed by specialized operators. This drug can be assumed at the patients’ home for long amounts of time and does not present any important pharmacological interactions. Generally, NAC does not lead to allergies and does not cause adverse effects heavier than nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, flatus and gastroesophageal reflux.

From the patients’ point of view, NAC can also present different advantages: it could help reduce recurrent and febrile UTIs and the consequent antibiotic administration and sensibilization, which can lead to antibiotic resistance and/or related adverse effects. Overall, NAC could exert a crucial role even in improving microbiota preservation and reducing the development of antibiotic allergies.

From the patients’ parents’ point of view, which constitutes a fundamental issue in pediatrics, NAC could improve therapy compliance, since the antibiotics administration often raises concerns about parents’ compliance.

Focusing on welfare, the implementation of NAC use could reduce the hospitalization rate and costs, as well as the health spending related to UTIs and their complications, particularly the antibiotics-related costs. Thus, it could lead to a global reduction of health system expenditure.

Considering all the above-mentioned factors, it is possible and could be advantageous to perform multicentric studies to study and implement NAC administration in pediatric urology.

7. Conclusions

Patient-side research is needed to improve our knowledge and our ability to apply NAC properties in pediatric urology. In particular, double-blind multicentered trials could allow us to validate the expected results of this work. Additionally, prospective randomized studies are required, each of them analyzing NAC effectiveness in each application context.

The implementation of NAC use also presents social advantages: it could reduce hospitalization costs and the health spending related to UTIs and their complications. Additionally, it could improve the global control of antibiotic resistance and thus reduce the antibiotic cost.

NAC could officially represent a very effective antimicrobial option in pediatric UTIs and should be evaluated as one of the next goals of research in this field, thanks to its adjuvant properties in bacterial biofilm treatment and to its anti-inflammatory effect. Its high tolerability and low cost make NAC worth having clinical validation in pediatric urology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.C. (Erica Clemente), M.D.C. and S.B.; methodology, E.C. (Erica Clemente), M.D.C., M.F., E.C. (Elisa Cerchia), M.C., S.G., S.G.N. and S.B.; software, E.C. (Erica Clemente), M.D.C. and S.B.; validation, S.G.N. and S.B.; formal analysis, E.C. (Erica Clemente), M.D.C., S.G. and S.G.N.; investigation, E.C. (Erica Clemente), M.D.C., M.F. and S.B.; resources, E.C. (Erica Clemente), M.D.C., E.C. (Elisa Cerchia) and M.C.; data curation, E.C. (Erica Clemente), M.D.C., S.G.N., S.G. and S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, E.C. (Erica Clemente), M.D.C., M.F., E.C. (Elisa Cerchia), M.C., S.G., S.G.N. and S.B.; writing—review and editing, E.C. (Erica Clemente), M.D.C., M.F., E.C. (Elisa Cerchia), M.C., S.G., S.G.N. and S.B.; visualization, E.C. (Erica Clemente), M.D.C., M.F., E.C. (Elisa Cerchia), M.C., S.G., S.G.N. and S.B.; supervision, M.F., E.C. (Elisa Cerchia), M.C., S.G., S.G.N. and S.B.; project administration, E.C. (Erica Clemente), M.D.C., S.G.N., S.G. and S.B.; funding acquisition, E.C. (Erica Clemente) and M.D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- EAU Guidelines on Paediatric Urology—EAU Guidelines, Proceedings of the EAU Annual Congress, Milan, Italy, 21–24 March 2023; European Association of Urology: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2023; ISBN 978-94-92671-19-6.

- Ladomenou, F.; Bitsori, M.; Galanakis, E. Incidence and Morbidity of Urinary Tract Infection in a Prospective Cohort of Children. Acta Paediatr. 2015, 104, e324–e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberici, I.; Bayazit, A.K.; Drozdz, D.; Emre, S.; Fischbach, M.; Harambat, J.; Jankauskiene, A.; Litwin, M.; Mir, S.; Morello, W.; et al. Pathogens Causing Urinary Tract Infections in Infants: A European Overview by the ESCAPE Study Group. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2015, 174, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, N.; Haralam, M.A.; Kurs-Lasky, M.; Hoberman, A. Association of Renal Scarring With Number of Febrile Urinary Tract Infections in Children. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, 949–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meena, J.; Thomas, C.C.; Kumar, J.; Raut, S.; Hari, P. Non-Antibiotic Interventions for Prevention of Urinary Tract Infections in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2021, 180, 3535–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgar, K. N-acetylcysteine: A review of clinical use and efficacy. Nutr. Med. J. 2022, 1, 26–45. [Google Scholar]

- Raghu, G.; Berk, M.; Campochiaro, P.A.; Jaeschke, H.; Marenzi, G.; Richeldi, L.; Wen, F.-Q.; Nicoletti, F.; Calverley, P.M.A. The Multifaceted Therapeutic Role of N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) in Disorders Characterized by Oxidative Stress. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2021, 19, 1202–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenório, M.C.d.S.; Graciliano, N.G.; Moura, F.A.; de Oliveira, A.C.M.; Goulart, M.O.F. N-Acetylcysteine (NAC): Impacts on Human Health. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tieu, S.; Charchoglyan, A.; Paulsen, L.; Wagter-Lesperance, L.C.; Shandilya, U.K.; Bridle, B.W.; Mallard, B.A.; Karrow, N.A. N-Acetylcysteine and Its Immunomodulatory Properties in Humans and Domesticated Animals. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinicola, S.; De Grazia, S.; Carlomagno, G.; Pintucci, J.P. N-Acetylcysteine as Powerful Molecule to Destroy Bacterial Biofilms. A Systematic Review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 18, 2942–2948. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Manoharan, A.; Ognenovska, S.; Paino, D.; Whiteley, G.; Glasbey, T.; Kriel, F.H.; Farrell, J.; Moore, K.H.; Manos, J.; Das, T. N-Acetylcysteine Protects Bladder Epithelial Cells from Bacterial Invasion and Displays Antibiofilm Activity against Urinary Tract Bacterial Pathogens. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoharan, A.; Farrell, J.; Aldilla, V.R.; Whiteley, G.; Kriel, E.; Glasbey, T.; Kumar, N.; Moore, K.H.; Manos, J.; Das, T. N-Acetylcysteine Prevents Catheter Occlusion and Inflammation in Catheter Associated-Urinary Tract Infections by Suppressing Urease Activity. Front Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1216798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Feky, M.A.; El-Rehewy, M.S.; Hassan, M.A.; Abolella, H.A.; Abd El-Baky, R.M.; Gad, G.F. Effect of Ciprofloxacin and N-Acetylcysteine on Bacterial Adherence and Biofilm Formation on Ureteral Stent Surfaces. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2009, 58, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schrier, B.P.; Lichtendonk, W.J.; Witjes, J.A. The Effect of N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine on the Viscosity of Ileal Neobladder Mucus. World J. Urol. 2002, 20, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Corte, M.; Fiori, C.; Popriglia, F. Is It Time to Define a “Neo-Urinary Tract Microbiota” Paradigm? Minerva Urol. Nephrol. 2023, 75, 552–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assefa, M.; Amare, A. Biofilm-Associated Multi-Drug Resistance in Hospital-Acquired Infections: A Review. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 5061–5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AbdelRazek, M.; Mohamed, O.; Ashour, R.; Alemam, M.; El-Gelany, M.; Abdel-Kader, M.S. Effect of Co-Trimoxazole and N-Acetylcysteine Alone and in Combination on Bacterial Adherence on Ureteral Stent Surface. Urolithiasis 2023, 52, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palleschi, G.; Carbone, A.; Zanello, P.P.; Mele, R.; Leto, A.; Fuschi, A.; Salhi, Y.A.; Velotti, G.; Rawashdah, S.A.; Coppola, G.; et al. Prospective Study to Compare Antibiosis versus the Association of N-Acetylcysteine, D-Mannose and Morinda Citrifolia Fruit Extract in Preventing Urinary Tract Infections in Patients Submitted to Urodynamic Investigation. Arch. Ital. Di Urol. E Androl. 2017, 89, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Marchiori, D.; Paolo Zanello, P. Efficacy of N-Acetylcysteine, D-Mannose and Morinda Citrifolia to Treat Recurrent Cystitis in Breast Cancer Survivals. In Vivo 2017, 31, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wong, K.K.; Kua, K.P.; Ooi, K.S.; Cheah, F.C. The Effects of N-Acetylcysteine on Lung Alveolar Epithelial Cells Infected with Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Malays J. Pathol. 2023, 45, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dronov, I.A.; Shakhnazarova, M.D. N-acetylcysteine in children: Current data and novel opportunities. Pulmonologiya 2017, 27, 811–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guerrero, C.A.; Torres, D.P.; García, L.L.; Guerrero, R.A.; Acosta, O. N-Acetylcysteine Treatment of Rotavirus-Associated Diarrhea in Children. Pharmacotherapy 2014, 34, e333–e340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de los Ángeles Durazo-Arvizu, M.; Azpeitia-Cruz, K.; Castillo, R.D.; Cano-Rangel, M.A.; Sotelo-Cruz, N. Usefulness of N-Acetylcysteine as Hepatoprotective Agent in Children Infected by Hepatitis A Virus. Pediatr. Oncall. J. 2018, 15, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotelo, N.; de los Angeles Durazo, M.; Gonzalez, A.; Dhanakotti, N. Early Treatment with N-Acetylcysteine in Children with Acute Liver Failure Secondary to Hepatitis A. Ann. Hepatol. 2009, 8, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Welling, M.C.; Johnson, J.A.; Coughlin, C.; Mulqueen, J.; Jakubovski, E.; Coury, S.; Landeros-Weisenberger, A.; Bloch, M.H. N-Acetylcysteine for Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Small Pilot Study. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 30, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.-M.; Lee, K.-M.; Lee, C.-Y.; Lee, H.-C.; Tam, K.-W.; Loh, E.-W. Effectiveness of N-Acetylcysteine in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2021, 55, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, M.H.M.; Danilovic, A.; Andrade, L.; Volpini, R.A.; Libório, A.B.; Sanches, T.R.C.; Seguro, A.C. N-Acetylcysteine Protects against Renal Injury Following Bilateral Ureteral Obstruction. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2008, 23, 3067–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, A.-H.; Wang, C.-J.; Lin, Y.-L.; Wang, C.-L.; Chiang, T.-I. N-Acetylcysteine Alleviates the Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease: A Three-Year Cohort Study. Medicina 2023, 59, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupp, K.; Madhivanan, P. Antibiotic Resistance in Prevalent Bacterial and Protozoan Sexually Transmitted Infections. Indian J. Sex Transm. Dis. AIDS 2015, 36, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocetto, F.; Balsamo, R.; Amicuzi, U.; De Luca, L.; Falcone, A.; Mirto, B.F.; Giampaglia, G.; Ferretti, G.; Capone, F.; Machiella, F.; et al. Novel Key Ingredients in Urinary Tract Health-The Role of D-Mannose, Chondroitin Sulphate, Hyaluronic Acid, and N-Acetylcysteine in Urinary Tract Infections (Uroial PLUS®). Nutrients 2023, 15, 3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemberger, U.; Quhal, F.; Bruchbacher, A.; Shariat, S.F.; Hiess, M. The Microbiome in Urinary Tract Infections in Children—An Update. Curr. Opin. Urol. 2021, 31, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

NAC’s most important properties include biofilm inhibition, preventing the formation of bacterial biofilms, which are protective layers that bacteria create to shield themselves from antibiotics; mucolytic effect, breaking down mucus and making it easier to clear; anti-inflammatory effect, reducing inflammation and helping to alleviate symptoms in various inflammatory conditions; antioxidant effect, neutralizing free radicals and protecting cells from oxidative stress and damage.

Figure 1.

NAC’s most important properties include biofilm inhibition, preventing the formation of bacterial biofilms, which are protective layers that bacteria create to shield themselves from antibiotics; mucolytic effect, breaking down mucus and making it easier to clear; anti-inflammatory effect, reducing inflammation and helping to alleviate symptoms in various inflammatory conditions; antioxidant effect, neutralizing free radicals and protecting cells from oxidative stress and damage.

Figure 2.

Current NAC applications in treating and preventing UTIs in adult patients: prophylaxis during urodynamic investigations, reducing the risk of infections during bladder function tests; preventing and treating CA-UTIs and stents-related UTIs, decreasing the incidence of infections linked to catheters and stents by inhibiting biofilm formation; modulating neo-urinary tract microbiota, balancing the urinary tract microorganisms to prevent infections; and treating recurrent cystitis in breast cancer survivors, improving quality of life by reducing infection recurrence and urogenital discomfort.

Figure 2.

Current NAC applications in treating and preventing UTIs in adult patients: prophylaxis during urodynamic investigations, reducing the risk of infections during bladder function tests; preventing and treating CA-UTIs and stents-related UTIs, decreasing the incidence of infections linked to catheters and stents by inhibiting biofilm formation; modulating neo-urinary tract microbiota, balancing the urinary tract microorganisms to prevent infections; and treating recurrent cystitis in breast cancer survivors, improving quality of life by reducing infection recurrence and urogenital discomfort.

Figure 3.

Current NAC applications in the pediatric field include its use in treating respiratory tract infections, where it acts as an effective mucolytic, preventing and disrupting bacterial biofilms. In cases of rotavirus infections, NAC reduces the number of diarrheal episodes and hastens symptom resolution, preventing severe dehydration. It is hepatoprotective in hepatitis A virus infections, significantly reducing liver enzymes and improving clinical outcomes. In pediatric neuropsychiatric disorders (e.g., obsessive–compulsive and autism spectrum disorders) it has been shown to reduce irritability and hyperactivity while enhancing social awareness. These diverse applications highlight NAC’s excellent tolerability and therapeutic potential in pediatric care.

Figure 3.

Current NAC applications in the pediatric field include its use in treating respiratory tract infections, where it acts as an effective mucolytic, preventing and disrupting bacterial biofilms. In cases of rotavirus infections, NAC reduces the number of diarrheal episodes and hastens symptom resolution, preventing severe dehydration. It is hepatoprotective in hepatitis A virus infections, significantly reducing liver enzymes and improving clinical outcomes. In pediatric neuropsychiatric disorders (e.g., obsessive–compulsive and autism spectrum disorders) it has been shown to reduce irritability and hyperactivity while enhancing social awareness. These diverse applications highlight NAC’s excellent tolerability and therapeutic potential in pediatric care.

Figure 4.

NAC potential future perspectives in pediatric urology. NAC provides significant kidney protection, improving renal function after bilateral ureteral obstruction and reducing the progression of chronic kidney disease. In treating recurrent UTIs, especially in young girls and adolescents, NAC could offer a novel approach by reducing bacterial adherence and colonization in the urinary tract, thus lowering antibiotic resistance risks. Additionally, NAC might serve as a prophylactic alternative to antibiotics in mini-invasive urological procedures, preventing antibiotic-associated side effects. Its role in preserving urinary microbiota homeostasis further underscores its potential to maintain long-term urinary health in children.

Figure 4.

NAC potential future perspectives in pediatric urology. NAC provides significant kidney protection, improving renal function after bilateral ureteral obstruction and reducing the progression of chronic kidney disease. In treating recurrent UTIs, especially in young girls and adolescents, NAC could offer a novel approach by reducing bacterial adherence and colonization in the urinary tract, thus lowering antibiotic resistance risks. Additionally, NAC might serve as a prophylactic alternative to antibiotics in mini-invasive urological procedures, preventing antibiotic-associated side effects. Its role in preserving urinary microbiota homeostasis further underscores its potential to maintain long-term urinary health in children.

Figure 5.

Principal possible positive aspects of a NAC implementation in the pediatric urology clinical setting: 1—NAC is already widely used in pediatric care, providing a strong foundation for its implementation in pediatric urology; 2—NAC is available in easily accessible formulations that can be administered at home without specialized medical personnel; 3—NAC has the potential to decrease the frequency of antibiotic use, reducing the risk of antibiotic resistance and related adverse effects; 4—implementing NAC could lead to lower hospitalization rates and reduced healthcare expenses associated with urinary tract infections (UTIs) and their complications, thereby decreasing overall health system costs.

Figure 5.

Principal possible positive aspects of a NAC implementation in the pediatric urology clinical setting: 1—NAC is already widely used in pediatric care, providing a strong foundation for its implementation in pediatric urology; 2—NAC is available in easily accessible formulations that can be administered at home without specialized medical personnel; 3—NAC has the potential to decrease the frequency of antibiotic use, reducing the risk of antibiotic resistance and related adverse effects; 4—implementing NAC could lead to lower hospitalization rates and reduced healthcare expenses associated with urinary tract infections (UTIs) and their complications, thereby decreasing overall health system costs.

Table 1.

Summary of current clinical evidence about NAC effectiveness in adult urology.

Table 1.

Summary of current clinical evidence about NAC effectiveness in adult urology.

| Authors/Year | Type | Dose | Results |

|---|

| AbdelRazek et al. 2023 [17] | Prospective randomized study | NAC (200 mg/day for children aged < 12 years old and 600 mg/day for adults) during stent indwelling | NAC and co-trimoxazole combination were more effective than either alone against bacterial infections in patients with JJ stent |

| Palleschi et al. 2017 [18] | Prospective randomized study | NAC two vials/day for 7 days | NAC and mannose prevent UTIs in patients undergoing urodynamics |

| Marchiori and Zanello 2017 [19] | Retrospective | NDM with NAC 100 mg, one vial every 12 h after emptying the bladder for 60 days and then one vial every 24 h after emptying the bladder for 4 months | NAC + D-mannose and Morinda citrifolia fruit extract improve the antibiotic therapy effectiveness in breast cancer survivors |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).