Comparison of Cardiorenal Syndrome and Heart Failure: A Preliminary Study of Clinical, Cognitive, and Emotional Aspects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

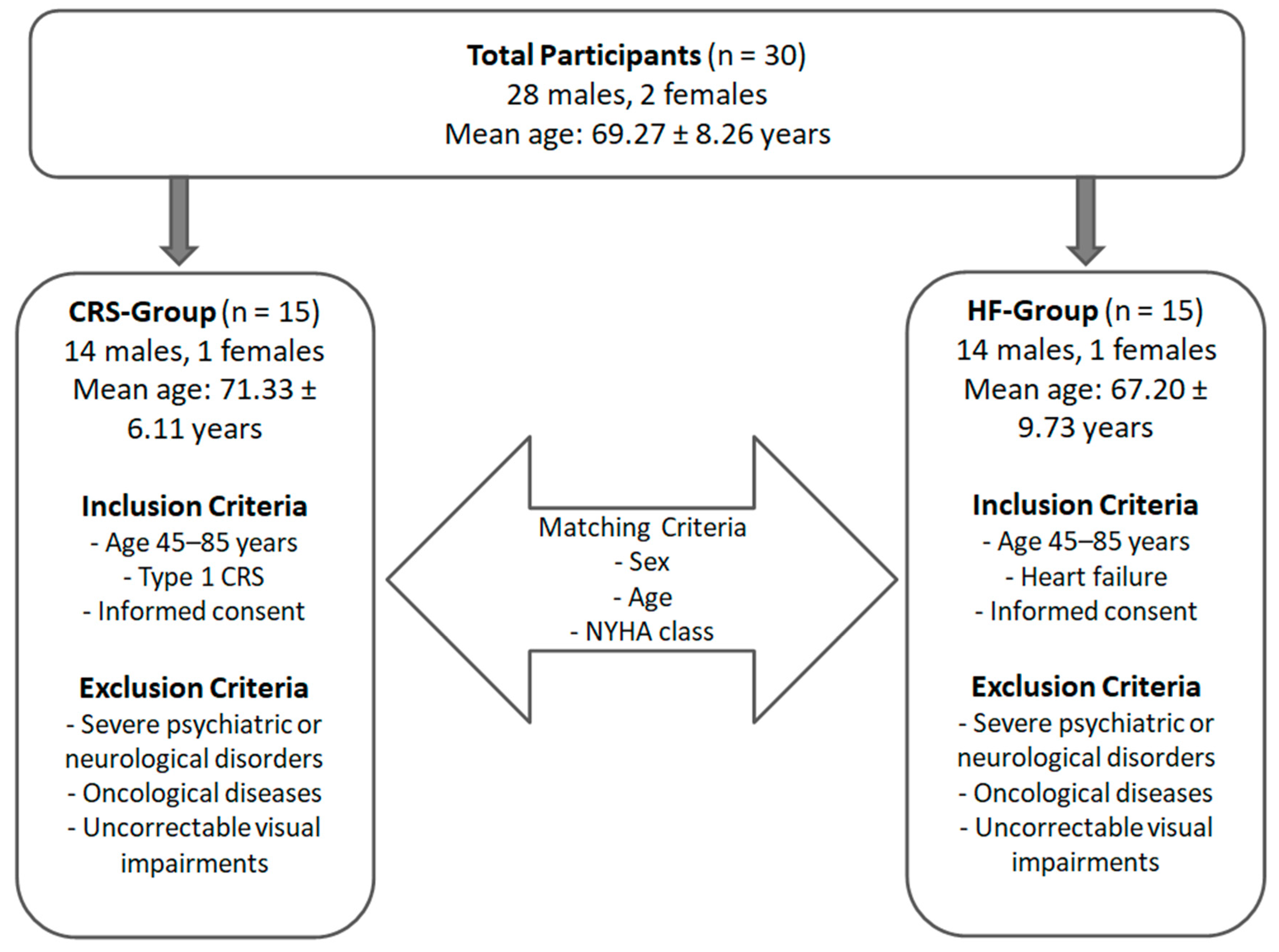

2.1. Population

2.2. Clinical Measures

2.3. Neuropsychological Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample

3.2. Clinical Measures Comparison

3.3. Equations Comparison

3.4. Neuropsycological Measures Comparison

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, G.; Liu, L.; Ma, Q.; He, H. Association between cardiorenal syndrome and depressive symptoms among the US population: A mediation analysis via lipid indices. Lipids Health Dis. 2024, 23, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, T.P. Genetic Markers of Cardiovascular Disease. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2024, 49, 102588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.M.; Parveen, S.; Williams, V.; Dons, R.; Uwaifo, G.I. Cardiometabolic comorbidities and complications of obesity and chronic kidney disease (CKD). J. Clin. Transl. Endocrinol. 2024, 36, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangaswami, J.; Bhalla, V.; Blair, J.E.A.; Chang, T.I.; Costa, S.; Lentine, K.L.; Lerma, E.V.; Mezue, K.; Molitch, M.; Mullens, W.; et al. American Heart Association Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease and Council on Clinical Cardiology Cardiorenal Syndrome: Classification, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment Strategies: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 139, e840–e878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lullo, L.; Reeves, P.B.; Bellasi, A.; Ronco, C. Cardiorenal Syndrome in Acute Kidney Injury. Semin. Nephrol. 2019, 39, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, U.; Wettersten, N.; Garimella, P.S. Cardiorenal Syndrome: Pathophysiology. Cardiol. Clin. 2019, 37, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Gao, W.; Xu, H.; Liang, W.; Ma, G. Role and Mechanism of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System in the Onset and Development of Cardiorenal Syndrome. J. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2022, 2022, 3239057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, A.A.; Anand, I.; Bellomo, R.; Cruz, D.; Bobek, I.; Anker, S.D.; Aspromonte, N.; Bagshaw, S.; Berl, T.; Daliento, L.; et al. Definition and classification of Cardio-Renal Syndromes: Workgroup statements from the 7th ADQI Consensus Conference. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2010, 25, 1416–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.A.; Wu, L.; Rodriguez, M.; Lentine, K.L.; Virk, H.U.H.; Hachem, K.E.; Lerma, E.V.; Kiernan, M.S.; Rangaswami, J.; Krittanawong, C. Recent Developments in the Evaluation and Management of Cardiorenal Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2023, 48, 101509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boriani, G.; Savelieva, I.; Dan, G.A.; Deharo, J.C.; Ferro, C.; Israel, C.W.; Lane, D.A.; La Manna, G.; Morton, J.; Mitjans, A.M.; et al. Chronic kidney disease in patients with cardiac rhythm disturbances or implantable electrical devices: Clinical significance and implications for decision making-a position paper of the European Heart Rhythm Association endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society. Europace 2015, 17, 1169–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khader, N.A.; Kamath, V.G.; Kamath, S.U.; Rao, I.R.; Prabhu, A.R. Kidney function estimation equations: A narrative review. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2025, 194, 725–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naher, A.; Wright, D.; Devonald, M.A.J.; Pirmohamed, M. Renal function monitoring in heart failure—What is the optimal frequency? A narrative review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makovski, T.T.; Schmitz, S.; Zeegers, M.P.; Stranges, S.; van den Akker, M. Multimorbidity and quality of life: Systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2019, 53, 100903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, J.; Han, D. Health-Related Quality of Life Based on Comorbidities Among Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2020, 11, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, A.; Ahmed, S.H.; El-Fetoh, N.M.; Mohamed, E.R. Quality of life of elderly cardiac patients with multimorbidity and burnout among their caregivers. Egypt. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 36, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulhaber-Walter, R.; Scholz, S.; Haller, H.; Kielstein, J.T.; Hafer, C. Health status, renal function, and quality of life after multiorgan failure and acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy. Int. J. Nephrol. Renov. Dis. 2016, 9, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Xiao, S.; Shi, L.; Zheng, X.; Xue, Y.; Yun, Q.; Ouyang, P.; Wang, D.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, C. Impact of Multimorbidity on Symptoms of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in Older Adults: Is There a Sex Difference? Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 762310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiriscau, E.I.; Bodolea, C. The Role of Depression and Anxiety in Frail Patients with Heart Failure. Diseases 2019, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laradhi, A.O.; Shan, Y.; Allawy, M.E. Psychological wellbeing and treatment adherence among cardio-renal syndrome patients in Yemen: A cross section study. Front. Med. 2025, 11, 1439704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroukian, S.M.; Schiltz, N.K.; Warner, D.F.; Stange, K.C.; Smyth, K.A. Increasing Burden of Complex Multimorbidity Across Gradients of Cognitive Impairment. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2017, 32, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.S.; Kim, E.J. A Correlative Relationship Between Heart Failure and Cognitive Impairment: A Narrative Review. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2023, 38, e334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Tong, S.; Chu, X.; Feng, T.; Geng, M. Chronic Kidney Disease and Cognitive Impairment: The Kidney-Brain Axis. Kidney Dis. 2022, 8, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano, M.; Corallo, F.; D’Aleo, P.; Duca, A.; Bramanti, P.; Bramanti, A.; Cappadona, I. A Set of Possible Markers for Monitoring Heart Failure and Cognitive Impairment Associated: A Review of Literature from the Past 5 Years. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrieta Valero, I. Autonomies in Interaction: Dimensions of Patient Autonomy and Non-adherence to Treatment. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Bahorik, A.L.; Dintica, C.S.; Yaffe, K. Cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome and incidence of dementia among older adults. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2025, 12, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Tan, L.; Guo, X.; Xu, Z.; Ye, R.; Zhang, M.; Zhuang, X.; Li, Z.; et al. Association of Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Syndrome With Cognitive Decline and Dementia: The ARIC Study Insights. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e038445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappadona, I.; Ielo, A.; Pagano, M.; Anselmo, A.; Micali, G.; Giambò, F.M.; Duca, A.; D’Aleo, P.; Costanzo, D.; Carcione, G.; et al. Observational protocol on neuropsychological disorders in cardiovascular disease for holistic prevention and treatment. Future Cardiol. 2025, 21, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Consultation. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation; World Health Organization Technical Report Series; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000; Volume 894, pp. 1–253. [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. ESC Scientific Document Group 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.A.; Riegel, B.; Bittner, V.; Nichols, J. Validity and reliability of the NYHA classes for measuring research outcomes in patients with cardiac disease. Heart Lung J. Crit. Care 2002, 31, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, M.; Mora Sánchez, M.G.; Bernal Amador, A.S.; Paniagua, R. The Metabolism of Creatinine and Its Usefulness to Evaluate Kidney Function and Body Composition in Clinical Practice. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockcroft, D.W.; Gault, M.H. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 1976, 16, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levey, A.S.; Stevens, L.A.; Schmid, C.H.; Zhang, Y.L.; Castro, A.F., 3rd; Feldman, H.I.; Kusek, J.W.; Eggers, P.; Van Lente, F.; Greene, T.; et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 150, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Epstein, N.; Brown, G.; Steer, R.A. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988, 56, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G. Beck Depression Inventory–II; APA PsycTests: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, R.M.; Banahan, B.F., 3rd; Holmes, E.R.; Patel, A.S.; Barnard, M.; Khanna, R.; Bentley, J.P. An evaluation of the psychometric properties of the sf-12v2 health survey among adults with hemophilia. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castel-Branco, M.M.; Lavrador, M.; Cabral, A.C.; Pinheiro, A.; Fernandes, J.; Figueiredo, I.V.; Fernandez-Llimos, F. Discrepancies among equations to estimate the glomerular filtration rate for drug dosing decision making in aged patients: A cross sectional study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2024, 46, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, P.E.; Levin, A. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Chronic Kidney Disease Guideline Development Work Group Members Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: Synopsis of the kidney disease: Improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158, 825–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassy, N.; Van Straaten, A.; Carette, C.; Hamer, M.; Rives-Lange, C.; Czernichow, S. Association of Healthy Lifestyle Factors and Obesity-Related Diseases in Adults in the UK. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2314741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huston, P. A Sedentary and Unhealthy Lifestyle Fuels Chronic Disease Progression by Changing Interstitial Cell Behaviour: A Network Analysis. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 904107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappadona, I.; Pagano, M.; Corallo, F.; Bonanno, L.; Crupi, M.F.; Lombardo, V.; Anselmo, A.; Cardile, D.; Ciurleo, R.; Iaropoli, F.; et al. Analysis of the clinical-organizational pathway and well-being of obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery: Impact on satisfaction and quality of life. Psychol. Health Med. 2025, 30, 1589–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvert, M.J.; Freemantle, N.; Cleland, J.G. The impact of chronic heart failure on health-related quality of life data acquired in the baseline phase of the CARE-HF study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2005, 7, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, A.; Teixeira-Pinto, A.; Lim, W.H.; Howard, K.; Chapman, J.R.; Castells, A.; Roger, S.D.; Bourke, M.J.; Macaskill, P.; Williams, G.; et al. Health-Related Quality of Life in People Across the Spectrum of CKD. Kidney Int. Rep. 2020, 5, 2264–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avagimyan, A.; Pogosova, N.; Fogacci, F.; Aghajanova, E.; Djndoyan, Z.; Patoulias, D.; Sasso, L.L.; Bernardi, M.; Faggiano, A.; Mohammadifard, N.; et al. Triglyceride-glucose index (TyG) as a novel biomarker in the era of cardiometabolic medicine. Int. J. Cardiol. 2025, 418, 132663, Erratum in Int. J. Cardiol. 2025, 421, 132907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2024.132907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avagimyan, A.; Fogacci, F.; Pogosova, N.; Kakrurskiy, L.; Kogan, E.; Urazova, O.; Kobalava, Z.; Mikhaleva, L.; Vandysheva, R.; Zarina, G.; et al. Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: 2023 Update by the International Multidisciplinary Board of Experts. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2024, 49, 102052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappadona, I.; Anselmo, A.; Cardile, D.; Micali, G.; Giambò, F.M.; Speciale, F.; Costanzo, D.; D’Aleo, P.; Duca, A.; Bramanti, A.; et al. Psychic and Cognitive Impacts of Cardiovascular Disease: Evidence from an Observational Study and Comparison by a Systematic Literature Review. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, D.; Kacso, I.; Avram, L.; Crisan, D.; Condor, A.; Bondor, C.; Rusu, C.; Potra, A.; Tirinescu, D.; Ticala, M.; et al. Mental Health and Kidneys: The Interplay Between Cognitive Decline, Depression, and Kidney Dysfunction in Hospitalized Older Adults. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, P.A.; Amin, A.; Pantalone, K.M.; Ronco, C. Cardiorenal Nexus: A Review With Focus on Combined Chronic Heart and Kidney Failure, and Insights From Recent Clinical Trials. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e024139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacoviello, M.; Gori, M.; Grandaliano, G.; Minutolo, R.; Pitocco, D.; Trevisan, R. A holistic approach to managing cardio-kidney metabolic syndrome: Insights and recommendations from the Italian perspective. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1583702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calça, R.; Malho, A.; Domingos, A.T.; Menezes Fernandes, R.; Gomes da Silva, F.; Aguiar, C.; Tralhão, A.; Ferreira, J.; Rodrigues, A.; Fonseca, C.; et al. Multidisciplinary cardiorenal program for heart failure patients: Improving outcomes through comprehensive care. Rev. Port. Cardiol. 2025, 44, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, M.; Corallo, F.; Anselmo, A.; Giambò, F.M.; Micali, G.; Duca, A.; D’Aleo, P.; Bramanti, A.; Garofano, M.; Bramanti, P.; et al. Optimisation of Remote Monitoring Programmes in Heart Failure: Evaluation of Patient Drop-Out Behaviour and Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, V.; Gangan, N.; Sheehan, J. Impact of cardiovascular complications among patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2015, 15, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salwa, K.; Kaziród-Wolski, K.; Rębak, D.; Sielski, J. The Role of Early Rehabilitation in Treatment of Acute Pulmonary Embolism-A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corallo, F.; Bonanno, L.; Di Cara, M.; Rifici, C.; Sessa, E.; D’Aleo, G.; Lo Buono, V.; Venuti, G.; Bramanti, P.; Marino, S. Therapeutic adherence and coping strategies in patients with multiple sclerosis: An observational study. Medicine 2019, 98, e16532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffo, R.; Urbinati, S.; Giannuzzi, P.; Jesi, A.P.; Sommaruga, M.; Sagliocca, L.; Bianco, E.; Tassoni, G.; Iannucci, M.; Sanges, D.; et al. Italian guidelines on cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: Executive summary. G. Ital. Cardiol. 2008, 9, 286–297. [Google Scholar]

| Criteria | CRS-Group | HF-Group |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion Criteria |

|

|

| Exclusion Criteria |

|

|

| Matching Criteria | Matched with HF group by Sex, Age, NYHA functional class | Matched with CRS group by: Sex, Age, NYHA functional class |

| Variables | CRS-Group | HF-Group | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n) | |||

| M | 14 | 14 | 1.00 |

| F | 1 | 1 | |

| Age mean (SD) | 71.33 (6.11) | 67.20 (9.73) | 0.17 |

| NYHA class (n) | |||

| I | 6 | 4 | 0.70 |

| II | 9 | 11 |

| Variable | CRS Mean (SD) | HF Mean (SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.43 (5.96) | 27.43 (5.54) | 0.99 |

| LVEF (%) | 51.60 (9.39) | 54.27 (9.06) | 0.44 |

| Serum Creatinine (mg/dL) | 2.45 (2.64) | 0.90 (0.23) | 0.03 |

| GFR-Cockcroft–Gault (mL/min) | 46.85 (22.78) | 96.25 (35.36) | 0.0001 |

| GFR-CKD-EPI (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 45.58 (26.50) | 85.93 (16.28) | <0.0001 |

| CRS-Group | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CKD Range (Value eGFR) | Equation Used | Subjects | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||

| Normal (eGFR ≥ 90) | Cockcroft–Gault | |||||||||||||||

| CKD-EPI | ||||||||||||||||

| Mild impairment (90 > eGFR ≥ 60) | Cockcroft–Gault | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| CKD-EPI | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Moderate impairment (60 > eGFR ≥ 30) | Cockcroft–Gault | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| CKD-EPI | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Severe impairment (30 > eGFR ≥ 15) | Cockcroft–Gault | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| CKD-EPI | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Kidney failure (eGFR < 15) | Cockcroft–Gault | X | ||||||||||||||

| CKD-EPI | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| HF-Group | ||||||||||||||||

| CKD Range (Value eGFR) | Equation Used | Subjects | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||

| Normal (eGFR ≥ 90) | Cockcroft–Gault | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| CKD-EPI | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Mild impairment (90 > eGFR ≥ 60) | Cockcroft–Gault | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| CKD-EPI | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Moderate impairment (60 > eGFR ≥ 30) | Cockcroft–Gault | X | ||||||||||||||

| CKD-EPI | X | |||||||||||||||

| Severe impairment (30 > eGFR ≥ 15) | Cockcroft–Gault | |||||||||||||||

| CKD-EPI | ||||||||||||||||

| Kidney failure (eGFR < 15) | Cockcroft–Gault | |||||||||||||||

| CKD-EPI | ||||||||||||||||

| Variable | CRS Mean (SD) | HF Mean (SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MoCA | 24.93 (3.41) | 24.67 (2.55) | 0.8103 |

| BDI-II | 11.33 (8.19) | 5.40 (6.68) | 0.0384 |

| BAI | 8.13 (4.73) | 4.67 (5.79) | 0.0834 |

| SF-12 Mental Score (%) | 66.42 (11.06) | 67.65 (9.64) | 0.7482 |

| SF-12 Physical Score (%) | 62.33 (5.63) | 63.00 (10.14) | 0.8255 |

| SF-12 Total Score (%) | 64.68 (6.57) | 65.68 (6.59) | 0.6811 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pagano, M.; Anselmo, A.; Micali, G.; Giambò, F.M.; Speciale, F.; Costanzo, D.; D’Aleo, P.; Duca, A.; Bramanti, A.; Garofano, M.; et al. Comparison of Cardiorenal Syndrome and Heart Failure: A Preliminary Study of Clinical, Cognitive, and Emotional Aspects. NeuroSci 2025, 6, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040129

Pagano M, Anselmo A, Micali G, Giambò FM, Speciale F, Costanzo D, D’Aleo P, Duca A, Bramanti A, Garofano M, et al. Comparison of Cardiorenal Syndrome and Heart Failure: A Preliminary Study of Clinical, Cognitive, and Emotional Aspects. NeuroSci. 2025; 6(4):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040129

Chicago/Turabian StylePagano, Maria, Anna Anselmo, Giuseppe Micali, Fabio Mauro Giambò, Francesco Speciale, Daniela Costanzo, Piercataldo D’Aleo, Antonio Duca, Alessia Bramanti, Marina Garofano, and et al. 2025. "Comparison of Cardiorenal Syndrome and Heart Failure: A Preliminary Study of Clinical, Cognitive, and Emotional Aspects" NeuroSci 6, no. 4: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040129

APA StylePagano, M., Anselmo, A., Micali, G., Giambò, F. M., Speciale, F., Costanzo, D., D’Aleo, P., Duca, A., Bramanti, A., Garofano, M., Bramanti, P., Corallo, F., & Cappadona, I. (2025). Comparison of Cardiorenal Syndrome and Heart Failure: A Preliminary Study of Clinical, Cognitive, and Emotional Aspects. NeuroSci, 6(4), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040129