Participation Outcomes One Year After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Associations with Cognition, Coping, and Psychological Distress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

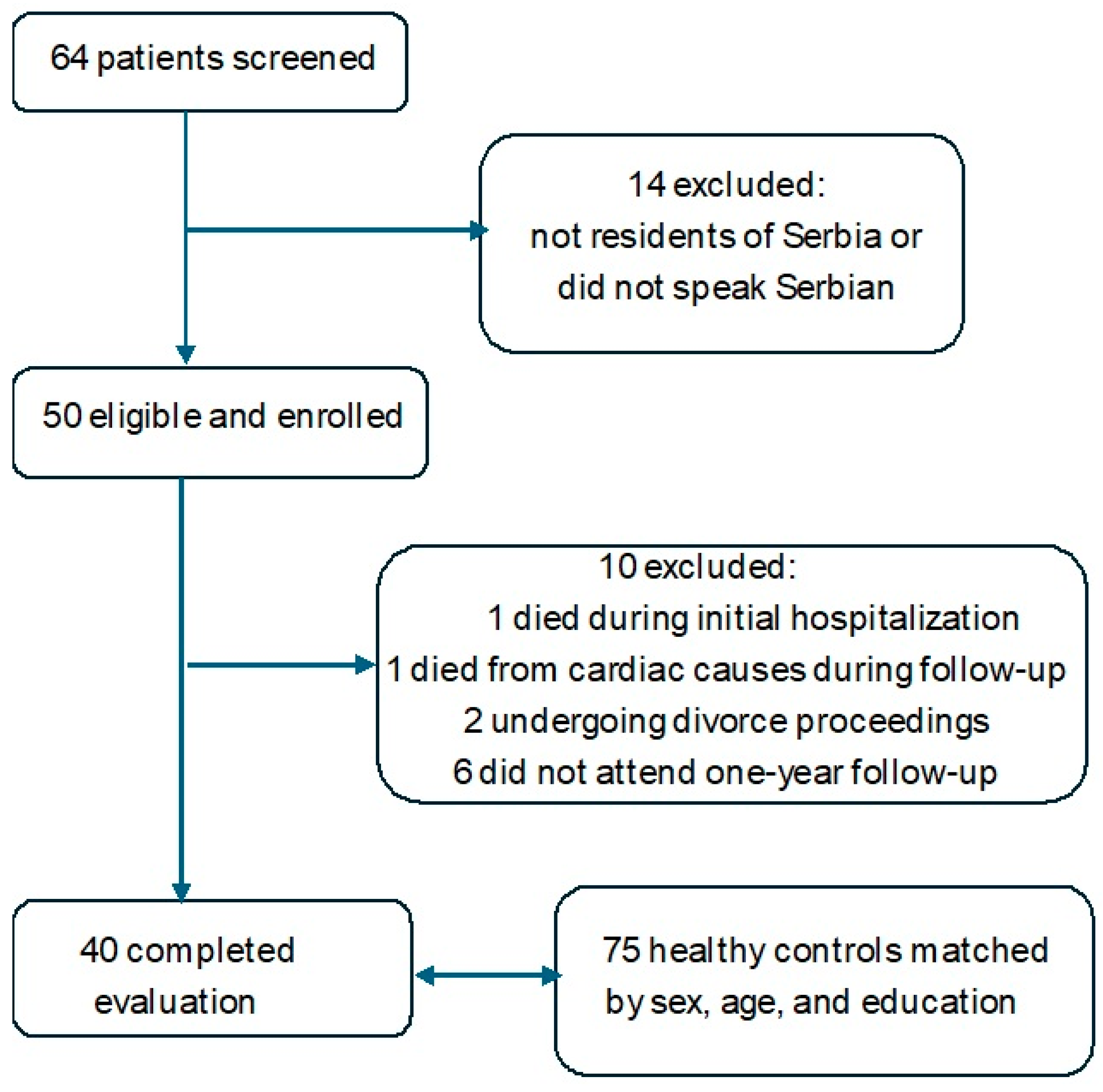

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Etminan, N.; Chang, H.S.; Hackenberg, K.; de Rooij, N.K.; Vergouwen, M.D.I.; Rinkel, G.J.E.; Algra, A. Worldwide incidence of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage according to region, time period, blood pressure, and smoking prevalence in the population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2019, 76, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, E.S., Jr.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Carhuapoma, J.R.; Derdeyn, C.P.; Dion, J.; Higashida, R.T.; Hoh, B.L.; Kirkness, C.J.; Naidech, A.M.; Ogilvy, C.S.; et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2012, 43, 1711–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser-Meily, J.M.; Rhebergen, M.L.; Rinkel, G.J.; van Zandvoort, M.J.; Post, M.W. Long-term health-related quality of life after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: Relationship with psychological symptoms and personality characteristics. Stroke 2009, 40, 1526–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Yassin, A.; Ouyang, B.; Temes, R. Depression and anxiety following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage are associated with higher six-month unemployment rates. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2017, 29, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, J.; Kitchen, N.; Heslin, J.; Greenwood, R. Psychosocial outcomes at 18 months after good neurological recovery from aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2004, 75, 1119–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wermer, M.J.; Kool, H.; Albrecht, K.W.; Rinkel, G.J. Aneurysm Screening after Treatment for Ruptured Aneurysms Study Group. Subarachnoid hemorrhage treated with clipping: Long-term effects on employment, relationships, personality, and mood. Neurosurgery 2007, 60, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.K.; Wang, L.; Tsoi, K.K.F.; Kim, J.M.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, J.S. Anxiety after subarachnoid hemorrhage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 3, 100060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiter, K.T.; Rosengart, A.J.; Claassen, J.; Fitzsimmons, B.F.; Peery, S.; Du, Y.E.; Connolly, E.S.; Mayer, S.A. Depressed mood and quality of life after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Neurol. Sci. 2013, 335, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermark, P.Y.; Schepers, V.P.; Post, M.W.; Rinkel, G.J.; Passier, P.E.; Visser-Meily, J.M. Longitudinal course of depressive symptoms and anxiety after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 53, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Vogelsang, A.C.; Forsberg, C.; Svensson, M.; Wengström, Y. Patients experience high levels of anxiety 2 years following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. World Neurosurg. 2015, 83, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turi, E.R.; Conley, Y.; Crago, E.; Sherwood, P.; Poloyac, S.M.; Ren, D.; Stanfill, A.G. Psychosocial comorbidities related to return to work rates following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2019, 29, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khindi, T.; Macdonald, R.L.; Schweizer, T.A. Cognitive and functional outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 2010, 41, e519–e526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huenges Wajer, I.M.; Visser-Meily, J.M.; Greebe, P.; Post, M.W.; Rinkel, G.J.; van Zandvoort, M.J. Restrictions and satisfaction with participation in patients who are ADL-independent after an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2017, 24, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruisheer, E.M.; Huenges Wajer, I.M.C.; Visser-Meily, J.M.A.; Post, M.W.M. Course of participation after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2017, 26, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, H.C.; Carlsson, L.; Sunnerhagen, K.S. Life situation 5 years after subarachnoid haemorrhage. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2018, 137, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passier, P.E.; Visser-Meily, J.M.; Rinkel, G.J.; Lindeman, E.; Post, M.W. Life satisfaction and return to work after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2011, 20, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, H.C.; Törnbom, K.; Sunnerhagen, K.S.; Törnbom, M. Consequences and coping strategies six years after a subarachnoid hemorrhage—A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafaji, H.; Nordenmark, T.H.; Western, E.; Sorteberg, W.; Karic, T.; Sorteberg, A. Coping strategies in patients with good outcome but chronic fatigue after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir 2023, 165, 1007–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerboom, W.; Heijenbrok-Kal, M.H.; van Kooten, F.; Khajeh, L.; Ribbers, G.M. Unmet needs, community integration and employment status four years after subarachnoid haemorrhage. J. Rehabil. Med. 2016, 48, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, W.E.; Hess, R.M. Surgical risk as related to time of intervention in the repair of intracranial aneurysms. J. Neurosurg. 1968, 28, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Swieten, J.C.; Koudstaal, P.J.; Visser, M.C.; Schouten, H.J.; Van Gijn, J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke 1988, 19, 604–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, C.S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief COPE. Int. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Post, M.W.; van der Zee, C.H.; Hennink, J.; Schafrat, C.G.; Visser-Meily, J.M.; van Berlekom, S.B. Validity of the Utrecht Scale for Evaluation of Rehabilitation-Participation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment MoCA: Abrief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornea, A.; Simu, M.; Rosca, E.C. Montreal Cognitive Assessment for evaluating cognitive impairment in subarachnoid hemorrhage: A systematic review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, H.C.; Törnbom, M.; Winsö, O.; Sunnerhagen, K.S. Symptoms and consequences of subarachnoid haemorrhage after 7 years. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2019, 140, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedlund, M.; Ronne-Engström, E.; Carlsson, M.; Ekselius, L. Coping strategies, health-related quality of life and psychiatric history in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Acta Neurochir. 2010, 152, 1375–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buunk, A.M.; Groen, R.J.; Veenstra, W.S.; Spikman, J.M. Leisure and social participation in patients 4–10 years after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Brain Inj. 2015, 29, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, E.A.; Boerboom, W.; van den Berg-Emons, R.H.J.G.; van Kooten, F.; Ribbers, G.M.; Heijenbrok-Kal, M.H. Fatigue in relation to long-term participation outcome in aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage survivors. J. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 53, jrm00173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patients (n = 40) | Controls (n = 75) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) female | 26 (65.0%) | 53 (66.3%) |

| Sex, n (%) male | 14 (35.0%) | 27 (33.7%) |

| Age at test, mean (SD) | 53.8 (9.8) | 53.1 (9.6) |

| Education: low/intermediate | 36 (90.0%) | 68 (90.7%) |

| Education: high | 4 (10.0%) | 7 (9.3%) |

| Marital status: Married | 23 (57.5%) | 50 (62.5%) |

| Divorced | 2 (5.0%) | 10 (12.5%) |

| Widowed | 8 (20.0%) | 5 (6.2%) |

| Single | 7 (17.5%) | 10 (12.5%) |

| Living with others | 37 (92.5%) | 68 (85.0%) |

| Living alone | 3 (7.5%) | 7 (8.8%) |

| Employed | 18 (45.0%) | 56 (70.0%) |

| Unemployed | 9 (22.5%) | 4 (5.0%) |

| Retired | 13 (32.5%) | 15 (18.8%) |

| Premorbid comorbidities: | ||

| Hypertension | 25 (62.5%) | 31 (38.8%) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 4 (10.0%) | 6 (7.5%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 7 (17.5%) | 9 (11.2%) |

| Diabetes | 6 (15.0%) | 2 (2.5%) |

| At least one comorbidity | 32 (80.0%) | 42 (52.5%) |

| Anterior circulation aneurysm | 37 (92.5%) | — |

| Posterior circulation aneurysm | 3 (7.5%) | — |

| HH grade I | 11 (27.5%) | — |

| HH grade II | 29 (72.5%) | — |

| Length of hospital stay (LOS), mean (SD) | 12.8 (5.9) | — |

| Rebleeding | 0 (0.0%) | — |

| Ischemia | 9 (22.5%) | — |

| Hydrocephalus | 2 (5.0%) | — |

| HADS—depression, mean (SD) | 5.0 (4.0) | 3.6 (2.8) |

| HADS—depression ≥ 8, n (%) | 9 (22.5%) | 1 (1.3%) |

| HADS—depression ≥ 11, n (%) | 4 (10.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HADS—anxiety, mean (SD) | 7.1 (4.5) | 5.0 (2.9) |

| HADS—anxiety ≥ 8, n (%) | 14 (35.0%) | 11 (13.8%) |

| HADS—anxiety ≥ 11, n (%) | 8 (20.0%) | 2 (2.5%) |

| MoCA, mean (SD) | 22.3 ± 5.3 | 27.2 ± 2.2 |

| MoCA ≤ 22, n (%) | 17 (42.5%) | 2 (2.7%) |

| Scale | Patients (n = 40) | Controls (n = 75) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HADS Anxiety | 7.1 (4.5) | 5.0 (2.9) | 0.079 |

| ≥8, n (%) | 16 (40.0%) | 14 (18.7%) | 0.024 |

| ≥11, n (%) | 8 (20.0%) | 2 (2.7%) | 0.003 |

| HADS Depression | 5.1 (4.0) | 3.6 (2.8) | 0.194 |

| ≥8, n (%) | 10 (25.0%) | 8 (10.7%) | 0.081 |

| ≥11, n (%) | 4 (10.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.013 |

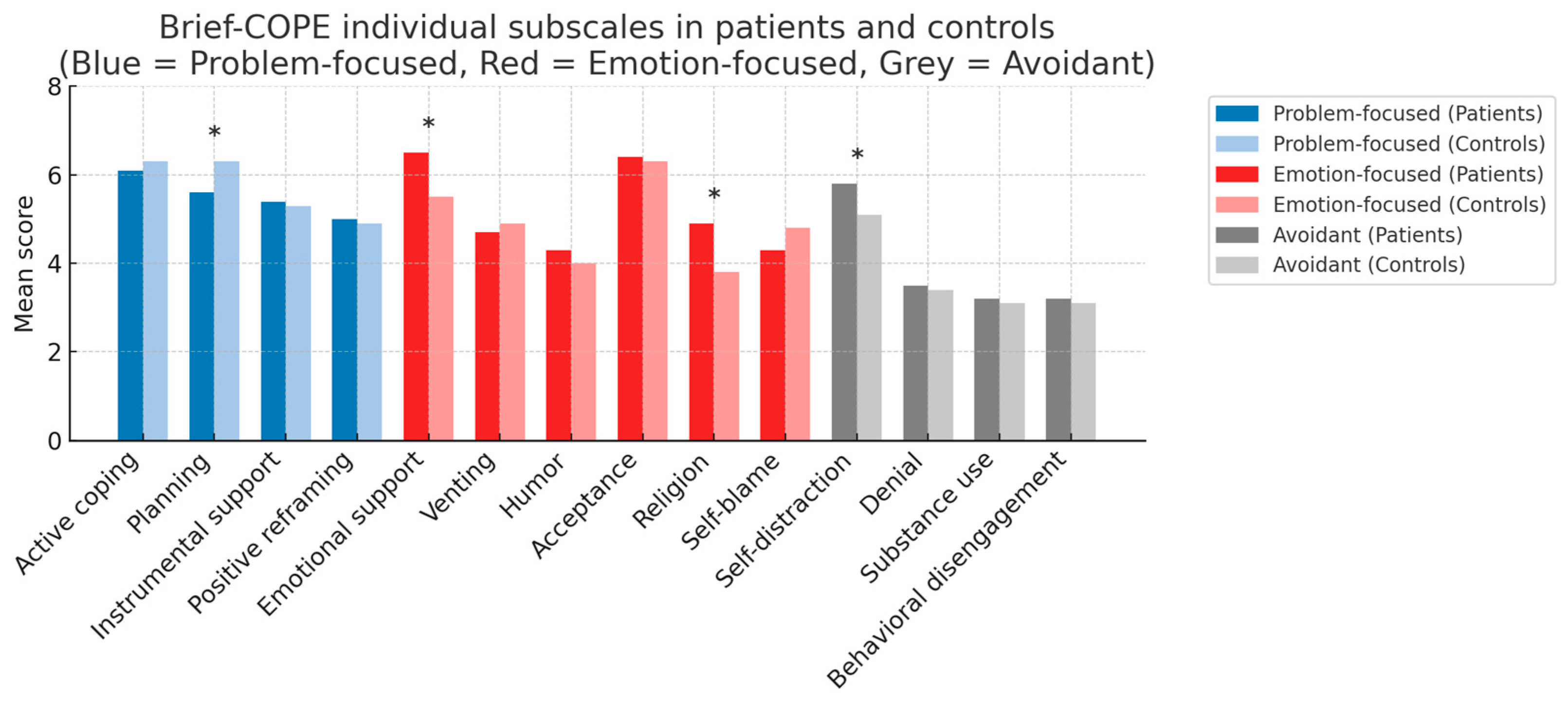

| Active coping | 21.95 (4.22) | 22.93 (4.71) | 0.242 |

| Emotional coping | 30.55 (5.58) | 28.85 (5.66) | 0.177 |

| Avoidant coping | 16.12 (3.76) | 14.72 (3.97) | 0.048 |

| MoCA | 22.3 ± 5.3 | 27.2 ± 2.2 | <0.001 |

| USER-P Frequency | 36.86 (14.14) 35 (28–51) | 49.92 (10.65) 51 (43–57) | <0.001 |

| USER-P Restrictions | 72.88 (26.07) 82 (58–92) | 96.28 (7.74) 100 (97–100) | <0.001 |

| USER-P Satisfaction | 62.00 (19.61) 65 (49–75) | 75.53 (13.08) 75 (70–85) | <0.001 |

| Activity | n with Restriction | % with Restriction | n Valid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paid work, unpaid work or education | 16 | 53% | 30 |

| Household duties | 17 | 44% | 39 |

| Outdoor mobility | 16 | 40% | 40 |

| Sports or other physical exercise | 20 | 54% | 37 |

| Going out | 10 | 30% | 33 |

| Day trips and other outdoor activities | 13 | 34% | 38 |

| Leisure activities at home | 14 | 36% | 39 |

| Relationship with your partner | 10 | 31% | 32 |

| Going to visit family or friends | 10 | 26% | 39 |

| Family or friends coming to visit | 6 | 15% | 40 |

| Contacting others by phone or computer | 7 | 18% | 39 |

| MoCA > 22 (n = 23) | MoCA ≤ 22 (n = 17) | p-Value | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participation frequency | 40.47 ± 14.12 | 31.98 ± 13.00 | 0.057 | d = 0.62 |

| Participation restrictions | 81.69 ± 21.24 | 60.96 ± 27.81 | 0.014 | r = 0.39 |

| Participation satisfaction | 67.07 ± 16.25 | 55.15 ± 22.09 | 0.070 | d = 0.63 |

| Outcome | Predictor | Standardized β | p-Value | Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restrictions Score | HADS Anxiety Skor | −0.33 | 0.015 | 0.48 |

| HADS Depression Skor | −0.31 | 0.019 | ||

| Avoidant coping | −0.27 | 0.042 | ||

| Employment | 0.21 | 0.093 | ||

| Age | −0.18 | 0.172 | ||

| Education | 0.16 | 0.198 | ||

| MoCA | 0.09 | 0.28 | ||

| Premorbid status | −0.12 | 0.47 | ||

| Frequency Score | HADS Anxiety Skor | −0.24 | 0.072 | 0.21 |

| Employment | 0.28 | 0.053 | ||

| Age | −0.19 | 0.166 | ||

| Avoidant coping | −0.15 | 0.202 | ||

| HADS Depression Skor | −0.14 | 0.225 | ||

| Education | 0.13 | 0.229 | ||

| MoCA | 0.32 | 0.045 | ||

| Premorbid status | −0.09 | 0.51 | ||

| Satisfaction Score | Employment | 0.41 | 0.002 | 0.52 |

| HADS Depression Skor | −0.35 | 0.011 | ||

| Avoidant coping | −0.29 | 0.034 | ||

| HADS Anxiety Skor | −0.12 | 0.263 | ||

| Age | −0.10 | 0.297 | ||

| Education | 0.11 | 0.282 | ||

| MoCA | 0.11 | 0.22 | ||

| Premorbid status | −0.18 | 0.42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pešterac-Kujundžić, A.; Nedeljković, U.; Sretenović, I.; Milosavljević, A.; Nestorovic, D.; Vukašinović, I.; Bogosavljević, V. Participation Outcomes One Year After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Associations with Cognition, Coping, and Psychological Distress. NeuroSci 2025, 6, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040128

Pešterac-Kujundžić A, Nedeljković U, Sretenović I, Milosavljević A, Nestorovic D, Vukašinović I, Bogosavljević V. Participation Outcomes One Year After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Associations with Cognition, Coping, and Psychological Distress. NeuroSci. 2025; 6(4):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040128

Chicago/Turabian StylePešterac-Kujundžić, Angelka, Una Nedeljković, Ivana Sretenović, Aleksandar Milosavljević, Dragoslav Nestorovic, Ivan Vukašinović, and Vojislav Bogosavljević. 2025. "Participation Outcomes One Year After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Associations with Cognition, Coping, and Psychological Distress" NeuroSci 6, no. 4: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040128

APA StylePešterac-Kujundžić, A., Nedeljković, U., Sretenović, I., Milosavljević, A., Nestorovic, D., Vukašinović, I., & Bogosavljević, V. (2025). Participation Outcomes One Year After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Associations with Cognition, Coping, and Psychological Distress. NeuroSci, 6(4), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040128