Clinical Validation of the SECONDs Tool for Evaluating Disorders of Consciousness in Argentina

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Formal Aspects

2.2. Sampling and Study Design

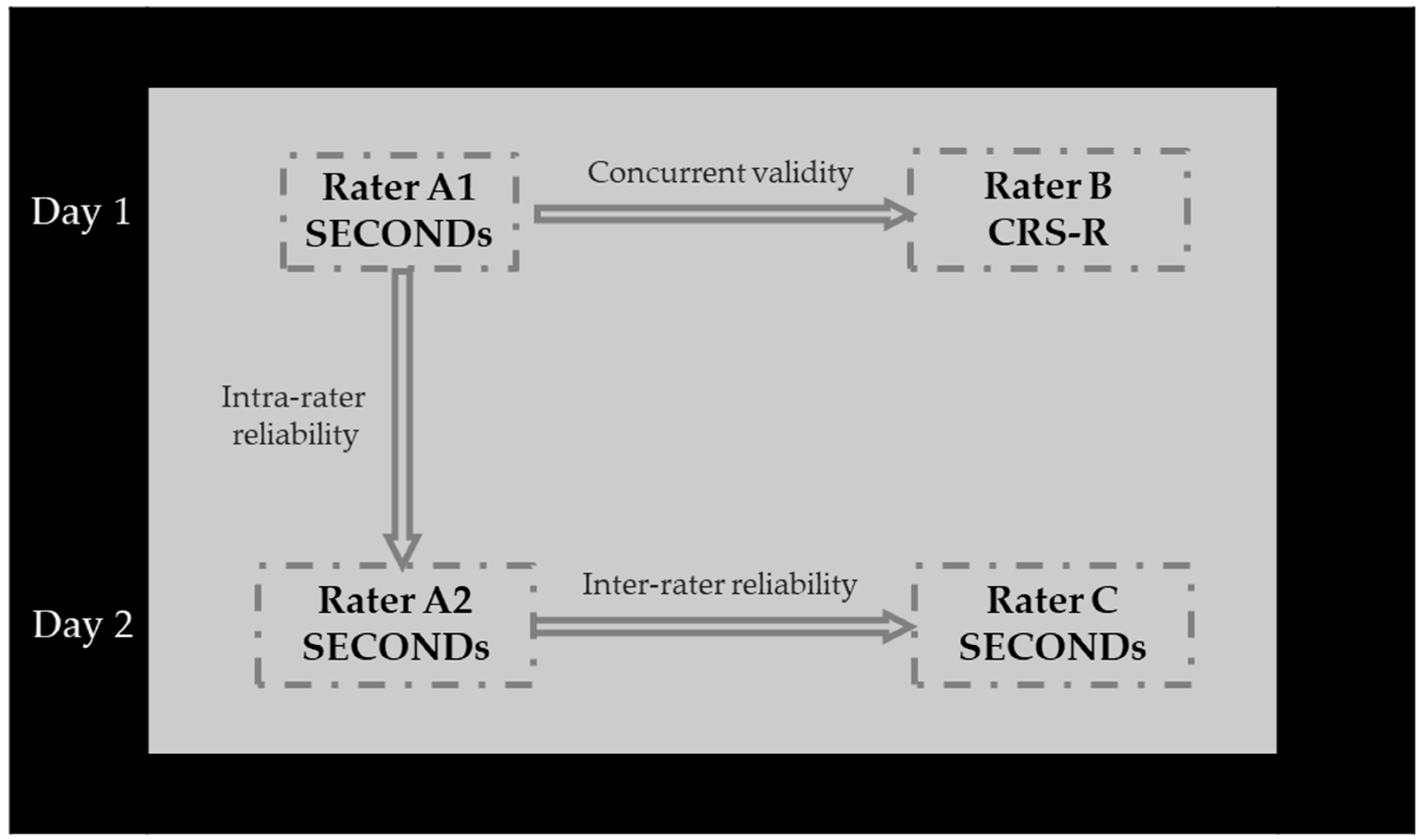

2.3. Assessment

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Coma Recovery Scale-Revised (CRS-R)

2.4.2. Simplified Evaluation of CONsciousness Disorders (SECONDs)

2.5. Translation

2.6. Procedure

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

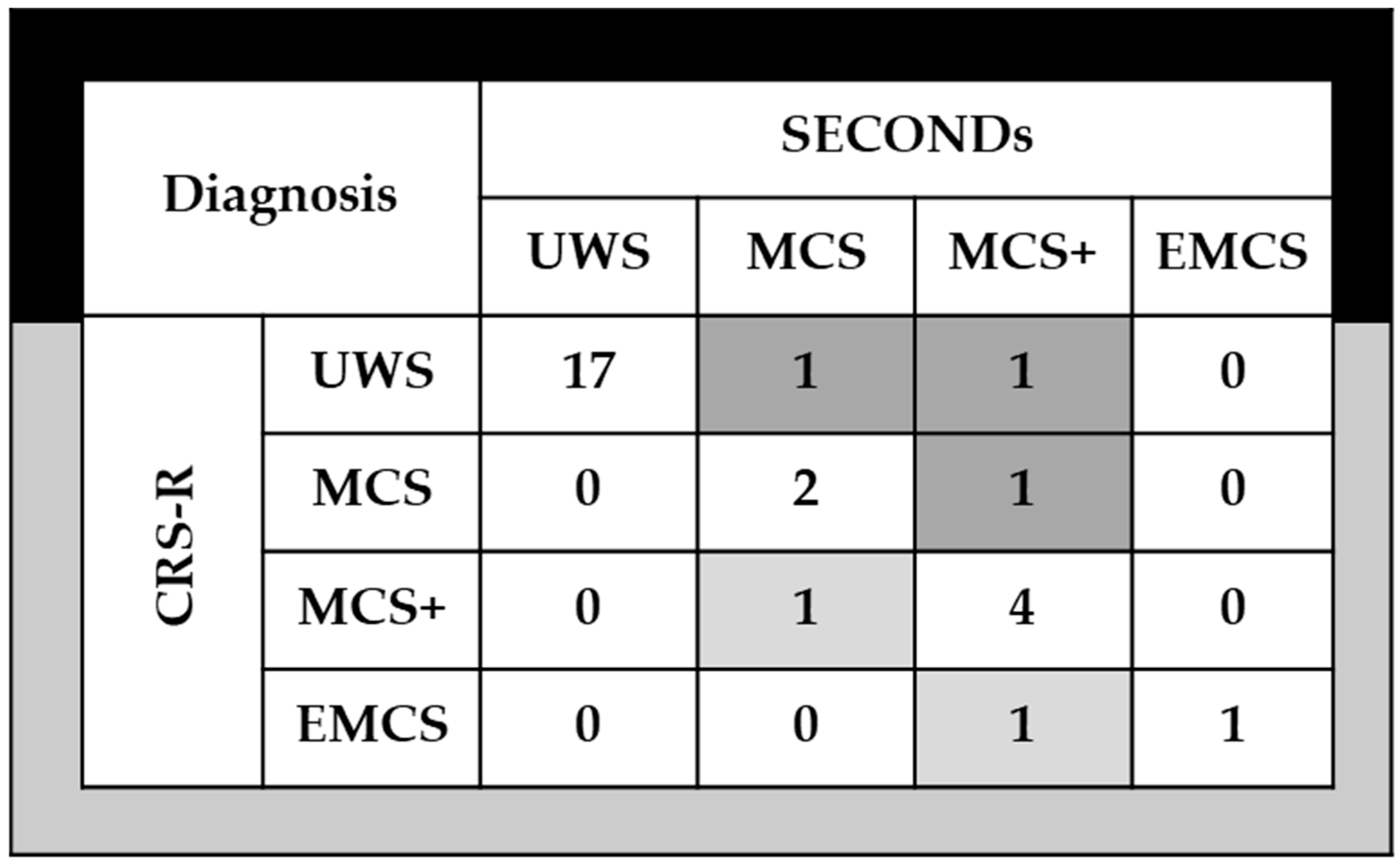

3.1. Concurrent Validity

3.2. Internal Consistency

3.3. Reliability

3.4. Clinical Utility

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications

4.2. Study Limitations

4.3. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRS-R | Coma Recovery Scale-Revised (CRS-R) |

| DoC | Disorders of Consciousness |

| SECONDs | Simplified Evaluation of Disorders of Consciousness |

References

- Plum, F.; Posner, J.B. The diagnosis of stupor and coma. Contemp. Neurol. Ser. 1972, 10, 1–286. [Google Scholar]

- Laureys, S.; Celesia, G.G.; Cohadon, F.; Lavrijsen, J.; León-Carrión, J.; Sannita, W.G.; Sazbon, L.; Schmutzhard, E.; Von Wild, K.R.; Zeman, A.; et al. Unresponsive wakefulness syndrome: A new name for the vegetative state or apallic syndrome. BMC Med. 2010, 8, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacino, J.T.; Ashwal, S.; Childs, N.; Cranford, R.; Jennett, B.; Katz, D.I.; Kelly, J.P.; Rosenberg, J.H.; Whyte, J.; Zafonte, R.D.; et al. The minimally conscious state: Definition and diagnostic criteria. Neurology 2002, 58, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacino, J.T.; Kalmar, K.; Whyte, J. The JFK Coma Recovery Scale-Revised: Measurement characteristics and diag-nostic utility. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004, 85, 2020–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodien, Y.G.; Carlowicz, C.A.; Chatelle, C.; Giacino, J.T. Sensitivity and Specificity of the Coma Recovery Scale–Revised Total Score in Detection of Conscious Awareness. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 97, 490–492.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatelle, C.; Bodien, Y.G.; Carlowicz, C.; Wannez, S.; Charland-Verville, V.; Gosseries, O.; Laureys, S.; Seel, R.T.; Giacino, J.T. Detection and Interpretation of Impossible and Improbable Coma Recovery Scale-Revised Scores. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 97, 1295–1300.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, A.; Lancioni, G.E.; Belardinelli, M.O.; Singh, N.N.; O’rEilly, M.F.; Sigafoos, J. Vegetative state: Efforts to curb misdiagnosis. Cogn. Process. 2009, 11, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnakers, C.; Vanhaudenhuyse, A.; Giacino, J.T.; Ventura, M.; Boly, M.; Majerus, S.; Moonen, G.; Laureys, S. Diag-nostic accuracy of the vegetative and minimally conscious state: Clinical consensus versus standardized neurobe-havioral assessment. BMC Neurol. 2009, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wannez, S.; Heine, L.; Thonnard, M.; Gosseries, O.; Laureys, S. The repetition of behavioral assessments in diagno-sis of disorders of consciousness. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 81, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stender, J.; Gosseries, O.; Bruno, M.-A.; Charland-Verville, V.; Vanhaudenhuyse, A.; Demertzi, A.; Chatelle, C.; Thonnard, M.; Thibaut, A.; Heine, L.; et al. Diagnostic precision of PET imaging and functional MRI in disorders of consciousness: A clinical validation study. Lancet 2014, 384, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curley, W.H.; Forgacs, P.B.; Voss, H.U.; Conte, M.M.; Schiff, N.D. Characterization of EEG signals revealing covert cognition in the injured brain. Brain 2018, 141, 1404–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitani, M.; Bodart, O.; Canali, P.; Seregni, F.; Casali, A.; Laureys, S.; Rosanova, M.; Massimini, M.; Gosseries, O. Transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with high-density EEG in altered states of consciousness. Brain Inj. 2014, 28, 1180–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodien, Y.G.; Giacino, J.T.; Edlow, B.L. Functional MRI Motor Imagery Tasks to Detect Command Following in Traumatic Disorders of Consciousness. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billeri, L.; Filoni, S.; Russo, E.F.; Portaro, S.; Militi, D.; Calabrò, R.S.; Naro, A. Toward Improving Diagnostic Strategies in Chronic Disorders of Consciousness: An Overview on the (Re-)Emergent Role of Neurophysiology. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacino, J.T.; Whyte, J.; Nakase-Richardson, R.; Katz, D.I.; Arciniegas, D.B.; Blum, S.; Day, K.; Greenwald, B.D.; Hammond, F.M.; Pape, T.B.; et al. Minimum Competency Recommendations for Programs That Provide Rehabilita-tion Services for Persons With Disorders of Consciousness: A Position Statement of the American Congress of Re-habilitation Medicine and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 1072–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubinet, C.; Cassol, H.; Bodart, O.; Sanz, L.R.; Wannez, S.; Martial, C.; Thibaut, A.; Martens, G.; Carrière, M.; Gosseries, O.; et al. Simplified evaluation of CONsciousness disorders (SECONDs) in individuals with severe brain injury: A validation study. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 64, 101432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, L.R.D.; Aubinet, C.; Cassol, H.; Bodart, O.; Wannez, S.; Bonin, E.A.C.; Barra, A.; Lejeune, N.; Martial, C.; Chatelle, C.; et al. Seconds administration guidelines: A fast tool to assess consciousness in brain-injured patients. J. Vis. Exp. 2021, 168, 61968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Sun, L.; Cheng, L.; Hu, N.; Chen, Y.; Sanz, L.R.D.; Thibaut, A.; Gosseries, O.; Laureys, S.; Martial, C.; et al. Validation of the simplified evaluation of consciousness disorders (SECONDs) scale in Mandarin. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2023, 66, 101764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noe, E.; Llorens, R.; Colomer, C.; Navarro, M.D.; O’Valle, M.; Moliner, B.; Ugart, P.; Olaya, J.; Barrio, M.; Ferri, J. Spanish validation of the Simplified Evaluation of Consciousness disorders (SECONDS). In Proceedings of the 7th European Congress of NeuroRehabilitation (ECNR), Lyon, France, 30 August–2 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wannez, S.; Gosseries, O.; Azzolini, D.; Martial, C.; Cassol, H.; Aubinet, C.; Annen, J.; Martens, G.; Bodart, O.; Heine, L.; et al. Prevalence of coma-recovery scale-revised signs of consciousness in patients in minimally conscious state. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2017, 28, 1350–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakiki, B.; Pancani, S.; De Nisco, A.; Romoli, A.M.; Draghi, F.; Maccanti, D.; Estraneo, A.; Magliacano, A.; Spinola, M.; Fasano, C.; et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and multicentric validation of the Italian version of the Simplified Evaluation of CONsciousness Disorders (SECONDs). PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossuyt, P.M.; Reitsma, J.B.; Bruns, D.E.; Gatsonis, C.A.; Glasziou, P.P.; Irwig, L.M.; Moher, D.; Rennie, D.; de Vet, H.C.; Lijmer, J.G.; et al. The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: Explanation and elaboration. Croat. Med. J. 2003, 44, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kitano, T.; Giacino, J.T.; Bodien, Y.; Waters, A.; Hioki, D.; Shinya, J.; Nakayama, T.; Ohgi, S. Reliability and validation of the Japanese version of the coma recovery scale-revised (CRS-R). Brain Inj. 2024, 38, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iazeva, E.G.; Legostaeva, L.A.; Zimin, A.A.; Sergeev, D.V.; Domashenko, M.A.; Samorukov, V.Y.; Yusupova, D.G.; Ryabinkina, J.V.; Suponeva, N.A.; Piradov, M.A.; et al. A Russian validation study of the Coma Recovery Scale-Revised (CRS-R). Brain Inj. 2018, 33, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Schnakers, C.; He, M.; Luo, H.; Cheng, L.; Wang, F.; Nie, Y.; Huang, W.; Hu, X.; et al. Validation of the Chinese version of the Coma Recovery Scale-Revised (CRS-R). Brain Inj. 2019, 33, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodien, Y.G.; Vora, I.; Barra, A.; Chiang, K.; Chatelle, C.; Goostrey, K.; Martens, G.; Malone, C.; Mello, J.; Parlman, K.; et al. Feasibility and Validity of the Coma Recovery Scale-Revised for Accelerated Standardized Testing: A Practical Assessment Tool for Detecting Consciousness in the Intensive Care Unit. Ann. Neurol. 2023, 94, 919–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine; Brain Injury-Interdisciplinary Special Interest Group; Disorders of Consciousness Task Force; Seel, R.T.; Sherer, M.; Whyte, J.; Katz, D.I.; Giacino, J.T.; Rosenbaum, A.M.; Hammond, F.M.; et al. Assessment Scales for Disorders of Consciousness: Evidence-Based Recommendations for Clinical Practice and Research. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010, 91, 1795–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamashiro, M.; Rivas, M.E.; Ron, M.; Salierno, F.; Dalera, M.; Olmos, L. A Spanish validation of the Coma Recovery Scale-Revised (CRS-R). Brain Inj. 2014, 28, 1744–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale | UWS | MCS | EMCS |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRS-R | Auditory ≦ 2 AND Visual ≦ 1 AND Motor ≦ 2 AND Oromotor/Verbal ≦ 2 AND Communication = 0 AND Arousal ≦ 2 | Auditory = 3–4 OR Visual = 2–5 OR Motor = 3–5 OR Oromotor/Verbal = 3 OR Communication = 1 | Motor = 6 Communication = 2 |

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, yr. (mean ± standard deviation) | 55.48 (16.28) |

| Gender distribution, male/female | 16/13 |

| Time post-injury, months (median [interquartile range]) | 20 (7.50–59.00) |

| CRS-R | |

| Total Score (median [interquartile range]) | 6 (4.00–11.00) |

| Duration of administration, minutes (median [interquartile range]) | 15 (10.00–16.00) |

| SECONDs, A1 rater | |

| Total Score (median [interquartile range]) | 1 (1.00–5.50) |

| Additional Index Score (median [interquartile range]) | 4 (3.00–25.00) |

| Duration of administration, minutes (median [interquartile range]) | 10 (9.00–12.00) |

| SECONDs, A2 rater | |

| Total Score (median [interquartile range]) | 1 (1.00–5.50) |

| Additional Index Score (median [interquartile range]) | 4 (4.00–32.50) |

| Duration of administration, minutes (median [interquartile range]) | 10 (9.00–10.15) |

| SECONDs, C rater | |

| Total Score (median [interquartile range]) | 1 (1.00–6.00) |

| Additional Index Score (median [interquartile range]) | 4 (3.50–33.50) |

| Duration of administration, minutes (median [interquartile range]) | 10 (9.00–12.50) |

| Etiology | |

| Anoxia | 15 (52%) |

| Trauma | 9 (31%) |

| Stroke | 5 (17%) |

| Clinical state according to Aspen Criteria | |

| UWS | 19 (65.52%) |

| MCS | 8 (27.58%) |

| EMCS | 2 (6.90%) |

| SECONDs Subscales | CRS-R |

|---|---|

| Communication | 0.45 * |

| Command-following | 0.51 ** |

| Oriented behaviors | 0.73 ** |

| Visual pursuit | 0.42 * |

| Visual fixation | 0.60 ** |

| Pain localization | 0.43 * |

| Arousal | 0.64 ** |

| Total SECONDs score | 0.73 ** |

| Additional index SECONDs score | 0.81 ** |

| SECONDs Subscales | Total SECONDs Score | Communication | Command- Following | Oriented Behaviors | Visual Pursuit | Visual Fixation | Pain Localization | Arousal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total SECONDs score | - | |||||||

| Communication | 0.57 ** | - | ||||||

| Command-following | 0.79 ** | 0.32 * | - | |||||

| Oriented behaviors | 0.73 ** | 0.29 * | 0.66 ** | - | ||||

| Visual pursuit | 0.89 ** | 0.41 * | 0.52 ** | 0.53 ** | - | |||

| Visual fixation | 0.90 ** | 0.42 * | 0.54 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.92 ** | - | ||

| Pain localization | 0.16 | −0.05 | −0.11 | −0.07 | 0.32 | 0.36 * | - | |

| Arousal | 0.34 * | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.38 * | 0.38 * | 0.11 | - |

| CCI | IC95% | F | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||||

| Intra-rater reliability | |||||

| Communication | 0.78 | 0.57 | 0.88 | 7.702 | <0.0001 |

| Command-following | 0.76 | 0.55 | 0.88 | 7.269 | <0.0001 |

| Oriented behaviors | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.97 | 27.465 | <0.0001 |

| Visual pursuit | 0.80 | 0.62 | 0.92 | 9.306 | <0.0001 |

| Visual fixation | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 81.500 | <0.0001 |

| Arousal | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.83 | 4.927 | <0.0001 |

| Total SECONDs score | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 109.299 | <0.0001 |

| Additional index SECONDs score | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.97 | 34.277 | <0.0001 |

| Inter-rater reliability | |||||

| Communication | 0.46 | 0.12 | 0.70 | 2.697 | 0.0005 |

| Command-following | 0.77 | 0.57 | 0.89 | 8.171 | <0.0001 |

| Oriented behaviors | 0.78 | 0.58 | 0.89 | 8.888 | <0.0001 |

| Visual pursuit | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.88 | 8.132 | <0.0001 |

| Visual fixation | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.94 | 16.360 | <0.0001 |

| Total SECONDs score | 0.86 | 0.72 | 0.93 | 12.850 | <0.0001 |

| Additional index SECONDs score | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 50.815 | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Russo, M.J.; Sampayo, M.d.l.P.; Arias, P.; García, V.; Gambero, Y.; Maiarú, M.; Deschle, F.; Pavón, H. Clinical Validation of the SECONDs Tool for Evaluating Disorders of Consciousness in Argentina. NeuroSci 2025, 6, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040100

Russo MJ, Sampayo MdlP, Arias P, García V, Gambero Y, Maiarú M, Deschle F, Pavón H. Clinical Validation of the SECONDs Tool for Evaluating Disorders of Consciousness in Argentina. NeuroSci. 2025; 6(4):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040100

Chicago/Turabian StyleRusso, María Julieta, María de la Paz Sampayo, Paula Arias, Vanina García, Yanina Gambero, Mariano Maiarú, Florencia Deschle, and Hernán Pavón. 2025. "Clinical Validation of the SECONDs Tool for Evaluating Disorders of Consciousness in Argentina" NeuroSci 6, no. 4: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040100

APA StyleRusso, M. J., Sampayo, M. d. l. P., Arias, P., García, V., Gambero, Y., Maiarú, M., Deschle, F., & Pavón, H. (2025). Clinical Validation of the SECONDs Tool for Evaluating Disorders of Consciousness in Argentina. NeuroSci, 6(4), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040100