Abstract

This study examines digital hospitality as a socio-technical system in which technological adoption and human resource (HR) practices jointly shape guest experiences and workforce dynamics. The research is situated at CitizenM hotels in Paris, a brand recognized for its integration of mobile applications, automated check-in, and the ambassador model of flexible role design. A mixed-methods approach was applied, combining a guest survey (n = 517) with semi-structured interviews with managers. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses confirmed a five-factor structure of guest perceptions: Digital Efficiency, Smart Personalization, Service Satisfaction, Trusted Security, and Digital Loyalty. Structural equation modeling showed that efficiency significantly drives satisfaction, while personalization and security strongly predict loyalty. Managerial insights revealed that these outcomes rely on continuous investment in training, mentorship, and flexible role allocation. Overall, the findings suggest that digital transformation enhances value creation not by substituting but by reconfiguring human service, with technology alleviating routine tasks and enabling employees to focus on relational and creative aspects of hospitality. The study concludes that effective digital hospitality requires the alignment of technological innovation with supportive HR practices, ensuring both guest satisfaction and employee motivation.

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, hospitality and tourism research has increasingly emphasized the transformative impact of digital technologies on the nature of service encounters [1,2,3]. Globally, the hospitality sector has witnessed a rapid acceleration of digital adoption. Mobile applications for booking and in-stay management are now widely used by international travelers, while automated kiosks have become standard features in both airports and urban hotels [4]. Digital payment systems dominate in Asia and North America [5,6], reflecting the maturity of mobile-first markets and guest expectations in these regions. In Europe, digitalization has been strongly associated with efficiency gains in hotel operations [7], whereas in East Asia—particularly China, Japan, and South Korea—integrated mobile ecosystems have redefined how guests interact with hospitality brands [8]. In Africa and Australia, investments in mobile platforms and cloud-based solutions are increasingly shaping competition across both leisure and business segments [9]. Taken together, these developments illustrate that digital hospitality is a global transformation, providing the backdrop for exploratory case-specific analyses such as Paris.

The rise of mobile applications [10,11], automated check-in systems [12,13], algorithmic personalization [14,15], and data-driven loyalty programs [16] illustrates how the sector has moved beyond traditional models of guest–staff interaction into what is often described as digitally mediated hospitality [17]. This development can be situated within the broader context of the experience economy [18], which highlights that value creation in contemporary services rests less on the provision of functional accommodation and more on the orchestration of memorable, efficient, and personalized experiences [19]. Technology, in this sense, operates not only as a facilitator of operational efficiency but also as a stage upon which new forms of experiential value are performed [20].

From a theoretical perspective, this evolution calls for a socio-technical lens. Classic socio-technical systems theory [21,22,23] argues that organizations achieve sustainable effectiveness when technological subsystems and social subsystems are aligned in mutually reinforcing ways. In hospitality, digital platforms provide unprecedented opportunities for automation, personalization, and data security [24], yet these benefits can only be realized when supported by human resource (HR) practices that ensure staff competence, adaptability, and motivation [25]. Without such alignment, digitalization risks producing what Orlikowski [26] describes as disjointed sociomateriality, where technological affordances are undercut by weak organizational integration.

The service-dominant logic of marketing [27] provides another conceptual foundation for interpreting digital hospitality. From this perspective, value is not embedded in technological products or processes themselves [28] but emerges through processes of co-creation between firms, employees, and customers [29]. Digital platforms thus function as enablers of resource integration [30], allowing guests to shape their experiences through mobile interaction [31] while employees deploy their skills and relational capacities in technologically augmented ways [32]. In parallel, research on technology acceptance and adoption [33,34] has highlighted that guest trust, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use are central in shaping satisfaction and loyalty outcomes [35,36], while employee acceptance depends on confidence, training, and organizational culture [37]. These insights emphasize that technology acceptance is not merely a matter of technical usability but of organizational readiness and cultural embedding [38].

These debates converge on the recognition that digitalization is not an isolated technological shift but a complex reconfiguration of both marketing and HR domains. Scholars of digital HRM [39,40] emphasize that digital tools transform not only how employees are trained and managed but also how they perceive their own roles, motivation, and identity within service organizations [41]. In hospitality specifically, this has led to new models of role design, such as the ambassador model employed by CitizenM [42], where employees are trained for multiple functions and supported through digital tools to focus more on relational and creative aspects of service delivery. Such hybrid arrangements resonate with the hybrid service models literature [43], which shows that neither fully automated nor fully traditional services are sufficient in heterogeneous markets; rather, the balance of digital efficiency and human interaction is what sustains competitiveness [44,45].

Against this theoretical backdrop, the present study addresses an important research gap. While existing scholarship has examined digitalization as a driver of guest satisfaction [46,47] or as a tool for HR efficiency [48], far less is known about how these two domains intersect and mutually constitute one another in practice. This paper therefore takes as its subject the alignment between guest perceptions of digital efficiency, personalization, satisfaction, trust, and loyalty on the one hand, and managerial practices of training, mentoring, and role flexibility on the other. The case of CitizenM hotels provides a critical empirical site for this investigation, as the brand is both highly digitalized and explicitly committed to innovative HR practices. This study is framed as an exploratory case study, aiming to generate insights into the socio-technical dynamics of digital hospitality rather than to produce broadly generalizable claims.

The aim of the study is to develop an integrated understanding of digital hospitality as a socio-technical system, demonstrating how marketing outcomes and HR dynamics together shape value creation. The central proposition of this study is that digital transformation in hospitality generates value only when technological adoption is embedded within organizational practices that sustain employee competence, motivation, and adaptability. In other words, the effectiveness of digital solutions depends not simply on their technical functionality but on the extent to which they are integrated with human resource strategies that support the workforce. Accordingly, the guiding hypothesis (H1) states that digital transformation enhances value creation when technological innovation is aligned with supportive HR practices.

This research makes three key contributions. Theoretically, it extends socio-technical systems theory by showing how its principles apply to digitally mediated hospitality, integrating insights from marketing and HRM. Empirically, it demonstrates, through the case of CitizenM, that digital hospitality requires the joint optimization of technological efficiency and human creativity. Practically, it underscores the importance for hotel managers of complementing digital innovations with sustained investment in training, mentoring, and flexible role allocation. By situating digital hospitality within a socio-technical systems framework, the study advances a more holistic understanding of how technology and HR practices jointly shape guest satisfaction, trust, and loyalty.

2. Literature Review

The transformation of hospitality under the influence of digitalization has been examined from multiple perspectives, which together provide the foundation for the present study. Central to these debates is the question of how technology enhances efficiency, personalization, service satisfaction, trust, and loyalty, while at the same time requiring complementary human resource and managerial practices to secure successful implementation. The design of the guest survey and the managerial interviews in this study was directly informed by these theoretical traditions. The first body of literature highlights the importance of technological efficiency in shaping service encounters. Building on the Technology Acceptance Model [33] and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology [34], researchers consistently show that ease of use and functional reliability are decisive for adoption and satisfaction. In hospitality, studies on self-service technologies demonstrate that mobile applications, automated check-in systems, and digital information provision reduce waiting times, minimize misunderstandings, and enhance the perception of service quality [49,50,51]. Survey items therefore captured the extent to which guests experienced digital solutions as quick, simple, intuitive, and helpful in streamlining the stay. These findings directly support H1, which proposes that perceived technological efficiency—through ease of use, speed, and reliability—positively influences guest satisfaction and perceived service quality.

Beyond efficiency, scholars have emphasized the role of personalization in creating memorable experiences. Pine and Gilmore’s notion of the experience economy and the principles of service-dominant logic both underline that value is co-created through tailored interactions rather than delivered as standardized outputs [52]. In the context of hospitality, personalization through algorithmic recommendations, targeted promotions, and lifestyle-based offers has been found to deepen emotional bonds and encourage repeat visits [53]. Items in the present survey were thus designed to reflect whether guests felt recognized as individuals, whether digital pro-motions aligned with their preferences, and whether personalized content contributed to loyalty. This body of research aligns with H2, which states that digital personalization strengthens emotional bonds and increases loyalty.

Service quality and satisfaction remain at the heart of customer experience research. Drawing on expectancy–disconfirmation theory [54], studies have shown that satisfaction emerges when services not only meet expectations but also provide innovative and distinctive elements [55,56]. In digitally intensive hotels, this includes the balance between human and technological touchpoints, perceptions of innovation, and the sense that technology enhances comfort [57]. Accordingly, survey items asked guests whether digital solutions improved their stay, whether they contributed to comfort and relaxation, and whether they positioned the hotel as more innovative compared to competitors. This reasoning supports H3, which emphasizes that satisfaction increases when digital solutions meet expectations and add innovative, distinctive elements while balancing human–technology touchpoints.

Another critical dimension in the literature is digital trust and security. Research on e-commerce adoption [58,59] stresses that trust in data protection, secure payments, and transparent communication is a prerequisite for continued engagement [60]. In the hospitality sector, where sensitive financial and personal information is exchanged, trust extends to perceptions of responsible data use and organizational integrity [61,62]. Items in the instrument therefore assessed the degree of confidence guests placed in data security, the reliability of payment systems, the transparency of information, and the contribution of secure digital solutions to brand trust. These arguments are consistent with H4, which proposes that trust in secure digital systems drives continued engagement and brand trust.

Finally, the literature on relationship marketing and customer loyalty emphasizes that loyalty cannot be reduced to satisfaction alone, but also reflects affective commitment, advocacy intentions, and perceptions of differentiation [63]. In digital contexts, loyalty is further reinforced by innovation and exclusivity, with digital ecosystems serving as a source of emotional connection and brand distinctiveness [64,65]. To capture this, the survey included items relating to revisit intentions, willingness to recommend, willingness to develop loyalty based on digital benefits, and the emotional connection fostered through digital experiences. This view underlies H5, which argues that loyalty in digital hospitality is shaped not only by satisfaction but also by emotional connection, advocacy, and perceived innovation/exclusivity

Importantly, these constructs cannot be fully understood without reference to the workforce dimension. Studies on digital HRM and organizational learning [66,67] stress that digital tools alter not only operational processes but also employee identity, motivation, and adaptability. In hospitality, models such as CitizenM’s ambassador approach illustrate how role flexibility [68], supported by digital platforms [69], enables employees to concentrate on relational and creative aspects of service. In the context of this study, “HR practices” are therefore defined broadly, encompassing both traditional HR functions (e.g., recruitment, training, and development) and digitally mediated managerial practices such as role flexibility, mentoring, and the integration of digital tools for service personalization. This broader understanding reflects the hybrid nature of HR in digitalized hotels, where workforce management and ser-vice design are increasingly interlinked. These insights support H6, which states that effective digital HR practices (role flexibility, mentoring, digital integration) enable and stabilize technology-driven guest outcomes.

Managerial interviews in this study were therefore structured to explore how training, mentoring, and flexible role allocation sustain the guest-facing outcomes measured in the survey. This integrated review shows that digital hospitality should be conceptualized as a socio-technical system, in which technology-driven guest perceptions are enabled and stabilized by human resource practices. The measurement model of this study was therefore carefully aligned with established literature, ensuring that constructs derived from prior research were adapted to the specific context of CitizenM hotels while remaining theoretically robust and comparable across settings.

3. Materials and Methods

The research adopts a pragmatist–constructivist epistemological stance, grounded in the assumption that knowledge about hospitality phenomena is best generated through the integration of multiple methodological perspectives. On the one hand, the quantitative strand reflects a post-positivist orientation, emphasizing measurement adequacy, construct validity, and model fit in order to generalize patterns in guest perceptions across a large sample. On the other hand, the qualitative strand is informed by a constructivist orientation, acknowledging that meanings of digitalization, personalization, and role flexibility are co-constructed by managers and employees in their everyday practices. By adopting a pragmatist position, the study does not treat these paradigms as mutually exclusive but instead leverages their complementarity: the survey data provide reliability, precision, and generalizability, while the interviews offer contextual depth and insight into lived organizational realities. This mixed epistemological stance aligns with current calls in hospitality research for methodological pluralism, recognizing that digital transformation in hotels is both a measurable structural process and a socially negotiated practice.

This study was conducted at CitizenM Paris as part of a broader investigation of five hotels in the CitizenM network. Fieldwork in Paris was undertaken over a full year (January–December 2024), enabling repeated engagement with the hotel environment at different points in time. This longitudinal design provided an opportunity to observe seasonal variation in guest profiles, occupancy levels, and staff–guest interactions, thereby offering a robust empirical foundation. The Paris property was selected due to its international clientele and its strategic position within the brand’s European portfolio. The study was conducted in two separate parts in Paris, designed deliberately to bridge the demand-side perceptions of guests with the supply-side perspectives of managers who enact and steward digital transformation in daily operations. Positioning Paris as the focal case within a larger chain context allowed the inquiry to concentrate on a high-throughput, internationally oriented urban property where digitally mediated service encounters are routine rather than exceptional. The case logic was instrumental—the site provides a dense interplay of technology, brand communication, and human resource practices—while remaining analytically transferable to comparable lifestyle-oriented hotels.

The first part comprised a structured guest survey administered across multiple fieldwork waves over a full annual cycle. The instrument operationalized five theoretically grounded constructs that connect marketing and HR through technology—digital efficiency, personalization, service satisfaction, trust and security, and loyalty—using a five-point Likert response format. The thematic domains of efficiency, personalization, satisfaction, security, and loyalty were derived from the literature on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), service-dominant logic (SDL), expectancy–disconfirmation theory, and relationship marketing, ensuring strong theoretical grounding of the instrument. Item generation followed a content-validity procedure: concept mapping against service-dominant logic and experience-economy tenets, review of recent hospitality digitalization literature, and expert appraisal to ensure clarity and coverage.

A pilot test (n = 25) was conducted with a small group of hotel guests representing diverse age groups and nationalities to ensure cross-cultural clarity of the survey. Feedback from the pilot led to several refinements: simplifying technical wording, reordering items to improve flow, and adjusting two items to remove potential ambiguity (e.g., replacing “platform responsiveness” with “speed of the mobile app”). The pilot confirmed that items were easily understood, the scale anchors were meaningful, and response distributions did not show acquiescence bias. To further mitigate common-method inflation, the final ordering of the questionnaire interleaved items from different constructs. This step strengthened the reliability and validity of the operationalization before the main data collection.

The analytic plan for the guest data followed a measurement-first logic. Dimensionality was explored with principal axis factoring using an oblique rotation on the expectation that the latent domains are conceptually correlated in lived service settings. Factor retention was triangulated through the Kaiser criterion, scree inflection, and parallel analysis to guard against over-extraction. Reliability and validity were then established through internal consistency estimates, composite reliability, and convergent validity, followed by discriminant validity checks using both the Fornell–Larcker criterion and heterotrait–monotrait ratios. The confirmatory phase specified a five-factor measurement model estimated with robust maximum likelihood; model adequacy was judged using a portfolio of fit indices rather than a single threshold, and residual diagnostics guided any theoretically justified localized adjustments. To enhance generalizability and substantively link marketing and HR questions, the protocol included tests of partial measurement invariance across theoretically relevant subgroups (e.g., business vs. leisure purpose; prior brand experience; heavy vs. light app users). Only after securing acceptable cross-group measurement properties was the structural layer specified to examine how technology-related perceptions propagate toward loyalty-relevant outcomes.

The target population comprised guests of CitizenM Paris who were surveyed during multiple fieldwork waves. To ensure statistical adequacy, sample size calculations were benchmarked against the conventional 95% confidence level with a 5% margin of error—the “95/5 rule” widely adopted in hospitality survey research [70]. Following Cochran’s formula with p = 0.50, this benchmark indicates a minimum of n ≈ 384 for large populations. Given CitizenM’s annual guest throughput of several hundred thousand across the network, the finite population correction was negligible. The realized dataset consisted of 520 questionnaires, of which 517 were retained as valid cases after data-quality checks and the exclusion of three incomplete responses. On this basis, the achieved sample surpasses the design threshold: at p = 0.50, the ex post margin of error is approximately ±4.3% at the 95% confidence level, confirming the adequacy of statistical precision for descriptive and inferential analyses.

The sample composition reflects an international and highly educated urban clientele. Gender distribution showed a slight female predominance (54.5% female; 45.5% male). Age was heavily concentrated among 35–44-year-olds (61.3%), with smaller shares in the 45–54 (16.4%) and 25–34 (8.7%) cohorts, indicating a mid-career, mobile traveler segment. Educational attainment was notably high: 70.0% held college/university degrees, and 11.6% reported postgraduate qualifications, while only a small minority reported secondary or elementary education. In terms of country of residence, the largest proportion of respondents came from France (28.4%), followed by substantial representation from the USA (15.5%), UK (15.5%), and Germany (11.6%). Additional significant groups included Italy (10.6%), Spain (9.7%), and China (8.7%), reflecting Paris’s position as a hub within both transatlantic and intra-European travel circuits. The purpose of stay was primarily leisure (69.1%), although nearly one quarter of respondents (23.2%) were business travelers, highlighting the hybrid positioning of CitizenM. The length of stay clustered around short city breaks, with two to three nights reported by 60.3% of respondents. Brand loyalty and technology adoption were highly pronounced. A large majority of respondents (70.0%) had previously stayed in a CitizenM hotel, indicating strong repeat visitation, while 93.4% reported using the CitizenM mobile application during their stay. This extremely high rate of digital uptake underscores the centrality of mobile technology in shaping guest experiences and service interactions within the CitizenM brand. This purposive timing and broad inclusion strategy ensured that the survey captured both routine and peak operational states, yielding a guest sample diverse enough to represent different travel purposes, national backgrounds, and degrees of digital adoption.

Data collection was based on a structured questionnaire designed to capture guest perceptions of digitally mediated service encounters at CitizenM hotels. The instrument originally contained 38 items, each measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Items were developed from a review of prior literature on digital hospitality, technology adoption, personalization, service quality, trust, and loyalty, and were adapted to the specific operational features of the CitizenM service model. A detailed mapping of each item to prior literature is shown in Appendix C. To ensure content validity, the draft questionnaire was reviewed by three academic experts in hospitality management and piloted with a small group of hotel guests (n = 25), leading to minor adjustments in wording for clarity and cultural appropriateness. The full set of 38 guest survey items is provided in Appendix A. The questionnaire covered several thematic domains. The first block focused on digital efficiency and functionality (e.g., ease of booking, app usability, queue reduction). A second block addressed personalization and marketing experiences (e.g., tailored offers, lifestyle match, service discovery). The third block targeted perceived service quality and satisfaction (e.g., innovation, pleasantness of stay, relaxation, overall satisfaction gain). A fourth block assessed trust and security (e.g., secure payment systems, responsible data use, brand trust, information sharing). Finally, a fifth block examined loyalty and revisit intention (e.g., intention to return, recommending the hotel, perceived technological differentiation). Demographic questions (gender, age, education, country of residence, purpose and length of stay, prior brand experience, app use) were also included to profile the sample and enable subgroup comparisons. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses subsequently indicated that 20 of the original 38 items exhibited strong loadings on their intended constructs, forming a clean five-factor structure: Service Satisfaction (4 items), Digital Efficiency (6 items), Smart Personalization (4 items), Trusted Security (4 items), and Digital Loyalty (3 items). Items with low loadings or problematic cross-loadings were excluded, although they had contributed to the initial breadth of coverage and thereby safeguarded content validity in the early stages of instrument development. The validation of the questionnaire through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses confirmed that guest perceptions of digital hospitality could be meaningfully structured into five distinct constructs. These constructs provided the empirical foundation for hypothesis development. To further explore how these dimensions interact and how they resonate with organizational practice, the study formulated a set of hypotheses and sub-hypotheses. The overarching proposition concerned the role of digital transformation as a bridge between marketing outcomes and workforce dynamics, while the sub-hypotheses specified directional relationships between individual factors derived from the guest survey and insights emerging from the managerial interviews. Importantly, the survey findings also informed the interview guide design, ensuring that managerial reflections were collected around the same domains—efficiency, personalization, satisfaction, security, and loyalty—that guests had evaluated in the questionnaire.

H1a.

(Guest efficiency–satisfaction link): Higher levels of Digital Efficiency are positively associated with greater Service Satisfaction, as digital tools reduce waiting times and streamline basic interactions, enabling guests to experience smoother stays.

H1b.

(Personalization–loyalty link): Smart Personalization is positively related to Digital Loyalty, since tailored offers, lifestyle matches, and discovery functions foster stronger emotional connections and repeat intention.

H1c.

(Security–trust–loyalty chain): Trusted Security exerts a positive influence on both Service Satisfaction and Digital Loyalty, reflecting guests’ reliance on data protection and secure payments as conditions for sustained brand commitment.

H1d.

(Human–digital balance): The positive effect of Digital Efficiency on Service Satisfaction is moderated by the perceived balance between digital interactions and human touch, as emphasized by managers; guests who value personal contact may respond less positively to purely automated solutions.

H1e.

(Workforce flexibility): The relationship between Smart Personalization and Digital Loyalty is strengthened in organizational contexts where the ambassador model promotes role flexibility and employee engagement, suggesting that personalization outcomes depend partly on staff readiness to adapt to guest expectations.

H1f.

(Training and mentorship): The impact of Digital Efficiency on Service Satisfaction is mediated by employee competence and confidence, which are sustained through digital training tools but reinforced by mentorship, underscoring the HR dimension of technology deployment.

Seventeen managers across functional domains and hierarchical levels were recruited purposively to encompass front office, operations, human resources, and training and development, reflecting the sociomaterial span of digital service delivery. Participants had between 3 and 15 years of professional experience in the hospitality sector, and at least 2 years within the CitizenM brand. They represented a range of hierarchical levels, including line managers, department heads, and senior managers, ensuring variation in perspectives on digital transformation and HR practices. This purposive approach ensured that participants were both knowledgeable about the brand’s digital practices and sufficiently diverse to capture multiple organizational viewpoints. The interview guide was built abductively: deductive prompts anchored in the constructs measured on the guest side were paired with open probes to elicit situated accounts of workflow redesign, role reconfiguration, skill development, and the calibration of human touch in an app-enabled service model. Interviews were recorded with consent, professionally transcribed, and pseudonymized; an audit trail preserved instrument iterations, memos, and coding decisions. The semi-structured interview guide is presented in Appendix B.

Autoethnography and sensory walking were integrated not as anecdotal embellishment but as systematic methods for documenting embodied and affective aspects of digital hospitality. Sensory walking was selected precisely because digital touchpoints—apps, kiosks, soundscapes of lobbies, lighting in self-service areas—do not only operate as cognitive interfaces but as environmental and emotional cues. Walks were distributed across the annual cycle and across dayparts to register variations in soundscapes, lighting, guest flow, and staff posture around kiosks and mobile interactions. Fieldnotes were written immediately after each walk to conserve affective detail; reflexive journaling tracked the researcher’s positionality, expectations, and interpretive shifts over time. The qualitative component was included to capture meanings and practices of digitalization that cannot be reduced to survey responses alone. While the quantitative survey provided reliable measurement of guest perceptions, the qualitative strand offered explanatory depth by revealing how managers and employees interpret, negotiate, and enact digital tools in everyday settings. Coding of interview transcripts and field materials proceeded iteratively, beginning with first-order emic expressions, moving to second-order themes, and converging on aggregate dimensions. These themes were not analyzed in isolation but were explicitly compared with the five quantitative constructs (efficiency, personalization, satisfaction, security, loyalty). In this way, the qualitative findings complemented the quantitative results by illuminating underlying mechanisms, contextualizing statistical relationships, and highlighting boundary conditions (e.g., the role of mentoring in strengthening the efficiency–satisfaction link).

In analysis, interview transcripts and field materials were coded in an iterative template approach that combined first-order emic terms with second-order themes, converging on aggregate dimensions that mirror and extend the guest-side constructs. Credibility and dependability were strengthened through coder calibration on a shared subset, negative-case analysis, and limited member reflections with managers to check the fidelity of emergent interpretations without devolving into consensus seeking.

Integration occurred at two levels. Methodologically, the quantitative and qualitative strands were designed with planned points of connection: constructs operationalized for guests informed the architecture of the interview guide, while qualitative themes fed back into the interpretation of measurement boundaries and the reading of cross-group equivalence. Substantively, the mixed-methods frame allowed the study to treat technology not merely as a marketing interface or an HR tool but as a sociotechnical bridge: a set of practices and artifacts that simultaneously shape brand promises, guest agency, employee discretion, and the choreography of front-stage and back-stage labor. This bridging orientation underpinned choices such as oblique rotations in factor analysis, invariance tests across usage patterns, and purposive selection of managerial roles most directly implicated in digital touchpoint delivery and training.

Quality assurance and ethics were integrated throughout. The survey instrument used proximal and psychological separation of predictors and outcomes, varied scale anchors, and anonymity assurances to reduce common-method bias; statistical post hoc checks provided an additional safeguard. The qualitative strand emphasized confidentiality, informed consent, and GDPR-compliant handling of any references to digital interactions or logs; no operational data were collected beyond self-reports. The researcher’s dual role as observer-participant was made explicit, and reflexive notes were used to surface and bracket preconceptions stemming from prior familiarity with hospitality technology. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the university’s research ethics committee (protocol code 139, 28 December 2023), which reviewed the procedures for anonymity, consent, and data security. Since the name of the hotel is disclosed, special safeguards were applied: guest responses were fully anonymized, managerial testimonies were pseudonymized, and participation was voluntary with no repercussions for declining or withdrawing. These measures ensured that respondents faced no risks to their privacy, employment, or future service relationships as a result of their involvement. Limitations relate to the single-city case design, brand-specific service architecture, and potential selection effects in both guest and manager participation; these are offset in part by the longitudinal fieldwork, subgroup measurement checks, and the cross-functional breadth of managerial voices.

Having established sample adequacy, data quality, and the breadth of managerial voices, the analytic procedure was structured in three phases to ensure both robustness and theoretical alignment.

First, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was applied to uncover the latent dimensionality of guest responses. Principal axis factoring with oblimin rotation was chosen given the expectation of correlated constructs. Factor retention was based on the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalues > 1), scree plot inflection, and parallel analysis, which together minimized risks of over- or under-extraction, while conceptual interpretability guided the final retention of five factors. Items were retained if they showed primary loadings ≥ 0.50 and cross-loadings < 0.30, thereby ensuring simple structure and conceptual clarity. This stage provided an initial, data-driven validation of the proposed constructs. Second, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to validate the measurement model suggested by EFA. The CFA model was estimated using robust maximum likelihood, with standard errors obtained via bootstrapping to ensure parameter stability. Multiple fit indices were evaluated, including χ2 significance test, CMIN/df ratio, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) with 90% confidence intervals and PCLOSE test. Additionally, parsimony-adjusted indices (PNFI, PCFI) and information criteria (AIC, ECVI) were used to evaluate model adequacy relative to alternative specifications. Convergent validity was tested using Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE), while discriminant validity was checked through the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio. Third, upon establishing a reliable and valid measurement model, the study proceeded to Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to examine hypothesized relationships between constructs. SEM was used not only to test direct paths (e.g., efficiency → satisfaction, personalization → loyalty) but also to evaluate moderation and mediation effects, consistent with the sub-hypotheses H1a–H1f. Moderation was assessed by comparing multi-group invariance models (e.g., heavy vs. light app users; leisure vs. business guests) and by including interaction terms where appropriate. Mediation was examined using bias-corrected bootstrapped indirect effects, which provided robust confidence intervals for paths involving training, mentorship, and workforce flexibility.

This layered approach—EFA to explore, CFA to confirm, SEM to test relationships—ensured that the study did not prematurely impose structure but instead iteratively validated the model. By sequencing the analyses in this way, the methodology provided a rigorous foundation for testing both the overarching hypothesis and its sub-hypotheses. Importantly, the qualitative strand was designed in parallel to illuminate how the constructs identified through EFA–CFA–SEM are enacted in practice, ensuring that the mixed-methods design remains integrative rather than sequentially fragmented. In sum, the Paris study advances a rigorous, theory-linked mixed-methods design that examines how digitally mediated service practices co-produce guest experiences and workforce dynamics. By structuring the inquiry in two discrete but integrated parts and by treating technology as a sociomaterial bridge between marketing and HR, the design furnishes a robust platform for analysis while deliberately withholding results in this section to keep the focus on methodological clarity, coherence, and analytic depth. The mixed-method design was not sequential but integrative: quantitative findings guided the interpretation of interview themes, while qualitative insights provided contextual depth and explanatory mechanisms for the quantitative relationships tested in the structural model.

4. Results

The adequacy of the data for factor analysis was first assessed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (Table 1). The KMO value was 0.898, which exceeds the recommended threshold of 0.80 and indicates a high degree of sampling adequacy [71]. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was highly significant (χ2 = 8745.593, df = 703, p < 0.001), confirming that the correlation matrix was not an identity matrix and that the variables shared sufficient common variance to justify factor extraction. Together, these results demonstrate that the dataset was well-suited for exploratory factor analysis.

Table 1.

KMO and Bartlett’s Test.

The exploratory factor analysis yielded a five-factor solution based on the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalues > 1). As shown in Table 2, these factors jointly accounted for 50.65% of the total variance after rotation. In social science research, explained variance values above 50% are generally considered acceptable for multidimensional constructs, particularly when the data are derived from complex behavioral surveys [71]. The extracted factors therefore provide a statistically adequate and conceptually meaningful representation of the underlying dimensions of guest perceptions. The variance explained is distributed relatively evenly across the five components, with the first factor contributing 12.79% after rotation, followed by 10.96%, 10.32%, 8.79%, and 7.79%, respectively. This distribution indicates the absence of a single dominant factor and suggests a multifaceted structure, which aligns with the theoretical expectation that guest experiences in hospitality are shaped by several interrelated dimensions rather than one overarching construct. The five-factor model thus balances statistical sufficiency with theoretical interpretability, making it suitable for subsequent confirmatory analysis and structural modeling.

Table 2.

Total Variance Explained.

A five-factor solution was retained and rotated obliquely to allow correlated dimensions (principal axis factoring, oblimin). The rotated pattern shows a clean simple structure with 20 retained indicators mapping unambiguously onto the theorized constructs: Digital Efficiency, Smart Personalization, Service Satisfaction, Trusted Security, and Digital Loyalty (Table 3). Primary loadings are uniformly strong (M = 0.746; range = 0.700–0.794), while the largest absolute cross-loading across all indicators is 0.092, and the mean of the maximum cross-loadings per item is 0.053, indicating negligible overlap across factors and excellent discrimination at the EFA stage. Convergent validity is supported at the measurement-exploratory level: the average of squared primary loadings (EFA-based AVE proxy) exceeds 0.50 for each construct (≈0.56 for Digital Efficiency; 0.62 for Smart Personalization; 0.54 for Service Satisfaction; 0.52 for Trusted Security; 0.55 for Digital Loyalty), providing a strong rationale to proceed to CFA for formal CR/AVE estimation and Fornell–Larcker/HTMT checks.

Table 3.

Rotated Factor Matrix.

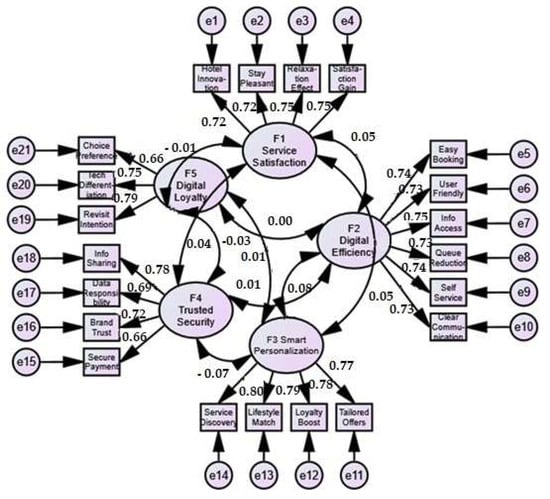

The confirmatory measurement model evidences excellent global fit. The χ2 test is non-significant (CMIN = 192.09, df = 179, p = 0.239), and the normed χ2 is near unity (CMIN/df = 1.07), indicating that the observed covariance matrix does not differ materially from the model-implied one. Incremental indices are uniformly high (CFI = 0.997, TLI = 0.996, IFI = 0.997; NFI = 0.956, RFI = 0.943), all at or above conventional benchmarks (≥0.95 for CFI/TLI/IFI; ≈0.90–0.95 for NFI/RFI). The RMSEA corroborates a close-fit interpretation (RMSEA = 0.012, 90% CI [0.000, 0.023], PCLOSE = 1.00), in stark contrast to the independence model (RMSEA = 0.185), and the population discrepancy measures are minimal (F0 ≈ 0.025; NCP = 13.09 with a CI including zero). Parsimony-adjusted indices are solid (PNFI = 0.741; PCFI = 0.772 with PRATIO = 0.775), suggesting that the very good fit is not achieved at the expense of excessive complexity. Information-theoretic and cross-validation criteria favor the specified model by a wide margin (AIC = 338.09 vs. 4370.94 for the independence model; ECVI = 0.651, lower than both saturated and independence alternatives), and the Hoelter critical N values (571 at α = 0.05; 611 at α = 0.01) far exceed the customary adequacy threshold of 200, implying model stability at the present sample size. Taken together, these diagnostics indicate that the five-factor measurement model provides a close and parsimonious representation of the data, suitable for subsequent structural analyses (Figure 1). As a good-practice complement, one might still inspect standardized residuals and modification indices, and verify multigroup measurement invariance (e.g., by purpose of stay or app use), but the aggregate evidence clearly supports retaining the current specification.

Figure 1.

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Source: Prepared by the authors (2025).

All constructs meet standard thresholds for convergent validity (AVE ≥ 0.50) and internal consistency (CR ≥ 0.70). Digital Efficiency and Smart Personalization show strong reliability and shared variance with their indicators (CR ≈ 0.86; AVE ≈ 0.56–0.62). Trusted Security also satisfies both criteria (CR ≈ 0.81; AVE ≈ 0.51). Digital Loyalty, with three indicators, attains acceptable reliability (CR ≈ 0.78) and AVE (0.54); if you wish to further strengthen this construct in CFA, consider reviewing the lowest-loading item (v37 = 0.656) for potential rewording or adding a theoretically coherent indicator, though this is not required given current adequacy.

Discriminant validity is strongly supported (Table 4 and Table 5). In the Fornell–Larcker matrix, the diagonal entries—square roots of AVE—for Service Satisfaction (0.736), Digital Efficiency (0.747), Smart Personalization (0.785), Trusted Security (0.716), and Digital Loyalty (0.734) all exceed the corresponding inter-construct correlations (|φ| ≤ 0.08). Hence, each construct shares more variance with its own indicators than with any other latent variable. The maximum shared variance across constructs is trivial (MSV = 0.082 = 0.0064), far below the lowest AVE (≈0.51), providing an additional check on discriminant adequacy.

Table 4.

Construct reliability and convergent validity.

Table 5.

Fornell–Larcker Criterion.

HTMT results converge on the same conclusion. All off-diagonal HTMT coefficients fall between 0.05 and 0.09—orders of magnitude below conservative cutoffs of 0.85 or 0.90—indicating that the constructs are near-orthogonal in the latent space. The presence of a three-item factor does not undermine this result: fewer items mainly widen bootstrap confidence intervals rather than inflate point estimates, and given the very low HTMT values observed, even conservative intervals would remain well under standard thresholds. Taken together with satisfactory CR and AVE, these diagnostics indicate a clean, well-separated measurement structure and a negligible risk of multicollinearity in subsequent structural analyses.

Having established through the guest survey a robust and discriminant measurement model, the analysis now shifts to the perspectives of managers to contextualize these guest-derived dimensions within organizational practice. While the quantitative strand captured how guests perceive efficiency, personalization, satisfaction, trust, and loyalty as distinct outcomes of their hotel experience, the qualitative strand illuminates how these same dimensions are enacted, balanced, and negotiated in everyday operations. Table 6 presents illustrative quotations from CitizenM Paris managers, offering insight into how digitalization and the ambassador model shape workforce dynamics and service delivery.

Table 6.

Illustrative Quotes from Manager Interviews (CitizenM, Paris).

The interviews with managers highlight complementary perspectives on how digitalization and the ambassador model shape everyday practices at CitizenM hotels in Paris. As shown in Table 6, the Front Office Manager emphasized that digital check-in and check-out reduce workload and allow staff to devote more time to personalized guest needs, although initial insecurity was observed among some employees who feared being replaced by technology. This reflects an important transitional dynamic: once technology is integrated, staff can reallocate their energy to higher-value interactions. The HR Manager’s perspective reinforces this by underscoring the motivational potential of the ambassador model. Flexibility in job roles fosters a sense of belonging and engagement, but it simultaneously increases training demands and energy expenditure. This duality illustrates the central HR challenge of ensuring that empowerment and workload remain in balance. From an operational standpoint, the Operations Manager noted that the key issue is not technology itself but the balance between digital and human interaction. Ambassadors are expected to adapt to varying guest expectations—ranging from fully digital to traditionally personal—suggesting that technology enhances rather than substitutes service. Finally, the Training & Development Manager drew attention to the importance of continuous learning. While digital training platforms accelerate onboarding and support self-paced learning, mentorship remains essential for transferring tacit knowledge and sustaining employee confidence. Together, these managerial insights suggest that digital technologies, while transformative, do not diminish the human element; rather, they reposition it within a more flexible and technologically supported framework. This interplay between efficiency, motivation, balance, and professional growth forms the backbone of CitizenM’s HR and service philosophy.

5. Discussion

The present study examined how digital technologies and human resource practices intersect in shaping guest perceptions and workforce dynamics within CitizenM hotels. By integrating survey-based structural validation with managerial interviews, the analysis provides a comprehensive understanding of how digital efficiency, personalization, satisfaction, trust, and loyalty manifest both at the level of guest experience and organizational practice.

5.1. Subsection Guest Perceptions of Digital Hospitality

The factor-analytic results reveal that guest experiences with digitally mediated hospitality services are far from monolithic. Instead of collapsing into a single global measure of satisfaction, the data demonstrate that guests differentiate clearly between five domains: efficiency, personalization, satisfaction, trust, and loyalty. The absence of a dominant factor and the balanced distribution of explained variance indicate that no single dimension exhausts the meaning of digital hospitality. This underscores the complexity of guest expectations in a technologically advanced service environment. The particularly high rate of mobile application usage provides strong evidence that guests regard digital touchpoints not as optional extras but as integral to the hospitality experience.

Digital efficiency—reflected in smooth booking, intuitive design, and queue reduction—emerged as a foundational driver of overall satisfaction, confirming H1a. This finding extends the assumptions of the Technology Acceptance Model [72,73] by showing that ease of use and perceived usefulness not only drive adoption but also directly contribute to service satisfaction in hospitality. Yet efficiency alone does not suffice: the distinctiveness of the personalization construct demonstrates that loyalty is cultivated less by speed and functionality and more by the ability of the system to adapt to individual needs. The confirmation of H1b points to a deeper emotional bond that emerges when guests feel recognized and valued through tailored content and customized offers. This resonates with service-dominant logic [74], which conceptualizes value as co-created rather than delivered, and contributes by demonstrating that algorithmic personalization in hospitality fosters durable loyalty outcomes.

Equally significant is the clear independence of trust-related perceptions from both efficiency and personalization. Guests do not assume that functional or personalized services automatically imply security; rather, they evaluate trust on its own terms. The support for H1c shows that secure payments, transparent communication, and responsible data use directly shape both satisfaction and loyalty. This contributes to the literature by conceptualizing trust not only as a hygiene factor s suggested in e-commerce studies [75] but also as a value-adding driver of brand attachment in hospitality.

The robustness of the digital loyalty construct, even though it was measured with only three items, adds a noteworthy layer to the findings. Guests are not merely satisfied or impressed with efficiency and personalization; they also translate these experiences into future-oriented behaviors such as repeat intention and recommendations. That such a parsimonious construct proved both reliable and valid indicates that digital loyalty is a crystallized outcome strongly shaped by antecedent perceptions. This study contributes by empirically clarifying the structure of digital loyalty as distinct from but interdependent with satisfaction, efficiency, personalization, and trust. Taken together, these results indicate that guest perceptions of digital hospitality are structured as a portfolio of interdependent but distinct dimensions. Improvements in one area—for example, app usability—do not automatically spill over into trust or loyalty. Each dimension requires strategic attention, and sustainable digital hospitality depends on simultaneously addressing efficiency, personalization, and security while ensuring that satisfaction and loyalty emerge as stable outcomes.

5.2. Managerial Perspectives and Workforce Dynamics

The managerial interviews provide an essential organizational lens through which the survey findings can be contextualized. Whereas the quantitative analysis highlighted the distinctiveness of efficiency, personalization, satisfaction, trust, and loyalty in shaping guest perceptions, the qualitative strand illustrates how these outcomes are enabled, balanced, and occasionally constrained in practice. From the Front Office perspective, digital tools were described as a mechanism for alleviating routine burdens and reallocating staff time to more meaningful guest engagement. This insight confirms H1d, since the relationship between efficiency and satisfaction does not operate in isolation but depends on the perceived balance between digital and human service. Technology is valuable not only because it accelerates transactions but also because it enables employees to redirect their energy toward tasks that enhance the human experience of hospitality. This finding empirically substantiates socio-technical systems theory [76] in hospitality by showing that efficiency outcomes depend on complementary human resource practices. However, the initial insecurity voiced by some employees reveals the transitional challenges that accompany digitalization: while efficiency gains are clear, staff acceptance requires reassurance that technology complements rather than replaces their roles.

The HR perspective further highlights the complexities of workforce adaptation. The ambassador model, which encourages role flexibility across functions, was reported to increase motivation and engagement by breaking down rigid job boundaries. This provides evidence for H1e, which suggests that the effectiveness of personalization in driving loyalty depends on employee adaptability and willingness to engage dynamically with guests. This study contributes by linking personalization outcomes to employee adaptability, thereby extending research on digital HRM [77] with evidence from a hospitality context. Yet the same model also demands higher levels of training and energy, indicating that flexibility, while empowering, can generate strain without sufficient organizational support. In this sense, the HR function must carefully calibrate empowerment strategies to ensure that engagement is sustained rather than eroded over time.

The Training & Development perspective offers a complementary dimension to this discussion. Managers emphasized that digital platforms for training accelerate onboarding and allow employees to learn at their own pace, but also underscored the irreplaceable role of mentorship in transmitting tacit knowledge and maintaining confidence. This observation supports H1f, which proposed that employee competence mediates the link between efficiency and satisfaction. This contributes to organizational learning theory [78] by demonstrating that digital training platforms are effective only when embedded in cultures of mentorship and peer support. Taken together, these insights demonstrate that digitalization does not simply operate at the level of guest-facing technologies but reshapes the very architecture of work in hospitality. Managerial perspectives confirm that the success of digital initiatives depends on organizational systems that balance technological integration with human adaptability, motivation, and mentorship. The qualitative strand therefore not only complements but also explains the mechanisms behind the quantitative findings, showing how digital hospitality is enacted through the interplay of tools, people, and practices.

5.3. Integrating Guest and Manager Perspectives

The integration of quantitative and qualitative findings highlights that CitizenM’s model of digital hospitality rests on a dual alignment: on one side, technology must deliver efficiency, personalization, and security to meet guest expectations; on the other, HR practices must ensure competence, flexibility, and motivation among employees. This study thus empirically substantiates socio-technical systems theory by showing that digital transformation generates sustainable value only when technological and human dimensions are harmonized. The survey results confirmed that digital efficiency, personalization, satisfaction, trust, and loyalty are distinct yet interrelated domains of the guest experience, while managerial insights revealed how these domains are enacted in daily practice. When alignment is achieved, digitalization enhances guest satisfaction, strengthens loyalty, and motivates employees by reallocating their energy from routine tasks to higher-value interactions. Conversely, misalignment—such as when automation is perceived as replacing rather than supporting human roles—risks employee insecurity and inconsistent guest experiences.

From a practical perspective, the findings suggest three key implications for hotel managers: (1) efficiency upgrades must be accompanied by staff retraining and reassurance to avoid alienation; (2) personalization requires investment in employee adaptability and cross-role flexibility; and (3) trust-building through secure payments, transparent communication, and responsible data handling should be treated as a strategic priority equal to efficiency and personalization. From a strategic perspective, these findings indicate that hotel managers should view efficiency, personalization, satisfaction, trust, and loyalty not as overlapping outcomes but as separate managerial priorities requiring coordinated investment. Upgrading digital infrastructure is necessary but insufficient; equal attention must be paid to training systems, mentoring practices, and flexible role design. Only through such integration can hotels ensure that digitalization contributes to service quality and long-term competitiveness rather than undermining the human dimension of hospitality.

At the same time, the study acknowledges several limitations. The empirical setting—a single hotel chain and one geographic location—limits the generalizability of the findings to broader hospitality contexts. A further limitation is reliance on self-reported data, which may reflect perceptual rather than behavioral engagement with digital tools. The cross-sectional design captures perceptions at a single moment in time, while the dynamic nature of digital transformation would benefit from longitudinal designs. Moreover, the managerial interviews, while rich in detail, are tied to one organizational and cultural environment. Future research should therefore explore comparative studies across hotel chains, regions, and digital strategies to assess how different contexts mediate the interplay between guest perceptions and workforce dynamics.

6. Conclusions

The integration of guest and managerial perspectives confirms that digital hospitality is best understood as a socio-technical system in which technology and human resources are mutually dependent. Survey results showed that efficiency, personalization, satisfaction, trust, and loyalty form distinct yet interrelated domains: efficiency drives satisfaction, personalization and trust underpin loyalty, and all contribute to a differentiated brand identity. Managerial insights revealed that these outcomes are sustainable only when employees are supported through structured HR practices, including digital training platforms, scenario-based learning modules, mentorship programs pairing experienced staff with newcomers, flexible role rotation under the ambassador model, and regular feedback and recognition mechanisms. These practices ensure that competence, motivation, and adaptability are maintained alongside digital adoption. Taken together, the findings confirm the central hypothesis (H1): digital transformation in hospitality enhances value creation when technological adoption is aligned with supportive HR practices. Technology alone cannot deliver sustainable improvements; only when embedded within organizational systems that empower staff and balance automation with the human touch can it generate satisfaction, loyalty, and workforce motivation.

At the same time, the study faces several limitations. Its focus on a single chain and city constrains generalizability, reliance on self-reported data introduces perceptual bias, and the cross-sectional design captures only one stage in an evolving process. Future research should therefore extend the analysis to multiple brands, cultural contexts, and longitudinal designs to examine how digital–human alignment evolves over time. In conclusion, CitizenM’s case demonstrates that the future of digital hospitality lies not in substituting human service but in repositioning it within a digitally enhanced framework of co-creation. By treating efficiency, personalization, security, satisfaction, and loyalty as coordinated strategic domains, supported by explicit HR measures such as continuous training, mentoring, workload balancing, and employee recognition, hotels can ensure that digital transformation translates into sustainable guest value while simultaneously strengthening long-term competitiveness.

Beyond the empirical setting, this study contributes to theory in several ways. First, it advances the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and related adoption frameworks by demonstrating that perceived usefulness and ease of use extend beyond adoption intention and translate directly into service satisfaction in hospitality. Second, it contributes to Service-Dominant Logic (SDL) by showing that personalization through digital systems can be conceptualized as a co-creation process, where loyalty arises not simply from functional service delivery but from the emotional resonance of being recognized and valued as an individual. Third, by applying socio-technical systems theory to a contemporary hospitality setting, the study illustrates that the outcomes of digital transformation cannot be understood apart from the organizational practices that support employees in adapting to new roles. Finally, the study enriches the literature on organizational learning by showing how digital training platforms are effective only when embedded within cultures of mentorship and peer support.

The practical implications of these findings extend to hotel managers, HR specialists, and policymakers. For managers, the message is clear: upgrading digital infrastructure must be coupled with systematic employee development, encompassing digital skills training, structured mentorship, flexible role design, and recognition systems that value adaptability. For HR professionals, the results highlight the importance of balancing empowerment and adaptability with adequate support systems to prevent fatigue and role strain. For policymakers and industry associations, the findings provide evidence that digital hospitality strategies should not be reduced to automation metrics but instead incorporate human development, trust-building, and workforce wellbeing as key performance indicators. Finally, this study also points to future research directions that go beyond hospitality. Comparative research across different service industries—such as banking, retail, or healthcare—could test whether the same portfolio of interdependent constructs (efficiency, personalization, satisfaction, trust, loyalty) holds in other digitally mediated contexts.

Longitudinal studies could explore whether digital loyalty, as clarified here, remains stable over time or evolves as technologies and guest expectations change. Future work could also assess cross-cultural variations in how guests perceive digital hospitality, particularly in regions where trust in data security or attitudes toward personalization may differ significantly. This research underscores that the digital transformation of hospitality is not merely a technological project but a deeply human and organizational endeavor. Only by aligning technological capabilities with clear and supportive HR strategies, ethical data governance, and a culture of learning and adaptability can hotels realize the promise of digital hospitality—one that enhances efficiency, fosters loyalty, builds trust, and motivates employees while maintaining the irreplaceable human dimension of service.

Contributions

Theoretical contributions. This study advances hospitality scholarship in several ways. First, it extends the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) by demonstrating that ease of use and perceived usefulness are not only antecedents of adoption but also predictors of service satisfaction in hospitality settings. Second, it enriches Service-Dominant Logic (SDL) by showing that personalization through digital systems functions as a co-creation process that deepens emotional bonds and drives loyalty. Third, it applies socio-technical systems theory to hospitality, illustrating that digital transformation outcomes cannot be understood apart from the HR practices that support employee adaptation. Finally, it contributes to organizational learning theory by demonstrating that digital training platforms are effective only when embedded in cultures of mentorship and peer support.

Practical contributions. For industry practice, the findings highlight that technology investments must be paired with strategic HR initiatives to ensure sustainable value creation. Managers should view efficiency, personalization, satisfaction, trust, and loyalty as distinct managerial priorities, each requiring tailored strategies. Specifically, the study underscores the need to (1) combine efficiency upgrades with staff retraining and reassurance to prevent alienation; (2) strengthen personalization outcomes through employee adaptability and flexible role design; and (3) prioritize trust-building via secure payments, transparent communication, and responsible data handling. More broadly, the study provides actionable guidance for hotel managers, HR specialists, and policymakers on how to balance automation with the human touch in digital hospitality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V. and N.R.; methodology, A.V., N.R., T.L. and N.S.; software, D.L.; validation, A.V. and N.R.; formal analysis A.V.; investigation, N.S., T.L., D.L. and N.R.; resources, A.V.; data curation, N.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.V.; writing—review and editing, A.V.; visualization, N.S.; supervision, A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Singidunum University (protocol code 139, 28 December 2023) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The aggregated data analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Guest Survey Items

(5-point Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree; items randomized in questionnaire to avoid priming and common-method bias)

- The app enabled me to manage most services without staff assistance.

- Digitalization made my stay more pleasant.

- Digital check-in and check-out saved me time.

- The hotel’s digital promotions matched my lifestyle and interests.

- I believe that digital solutions contribute to greater trust in the hotel brand.

- I would like to stay in this hotel again because of its digital benefits.

- Digitalization contributed to greater comfort during my stay.

- The app suggested content that was relevant to me.

- Transparency of information in the app increased my trust in the hotel.

- The hotel stands out from competitors due to the way it uses technology.

- The mobile app is intuitive and easy to use.

- I felt more relaxed thanks to digital solutions.

- The offers I received via the app were tailored to my needs.

- Digital payment systems appeared reliable and safe.

- I am willing to recommend this hotel to others because of its digital solutions.

- The balance between technology and the human touch was well maintained.

- I feel that the hotel cares about guests through digital innovations.

- I believe that personalized digital content increases my loyalty to the hotel.

- I trust the security of my personal data in the app.

- I would choose this hotel over others because of its innovative digital services.

- I believe the hotel is more efficient thanks to digital technologies.

- Personalized recommendations helped me discover new services and experiences.

- Innovative digital approaches increased my satisfaction with the stay.

- I would feel comfortable sharing additional personal information through the app.

- Hotel digitalization increases my willingness to become a loyal guest.

- The reservation process through the app was quick and simple.

- I consider the hotel innovative due to its digital technologies.

- I prefer hotels that use digital marketing to create customized offers.

- Digital communication with the hotel was confidential and secure.

- Digital experiences here make me feel emotionally connected to the brand.

- Digital solutions reduced the need to wait at the reception.

- I feel that digitalization improved my overall stay experience.

- The hotel’s digital marketing made me feel special as a guest.

- I am confident that the hotel uses my data responsibly.

- Digitalization improved my impression of the hotel compared to competitors.

- Digital tools in the hotel reduced possible misunderstandings during my stay.

- All necessary hotel information was available digitally.

- Digital solutions did not reduce the quality of service.

Appendix B. Semi-Structured Interview Guide for Managers

- Can you briefly describe your role in the hotel and your experience with the CitizenM ambassador model?

- How have digital tools (apps, check-in kiosks, internal software) changed the way employees perform their daily tasks?

- In your view, what are the main advantages and challenges of using these tools in hotel operations?

- How do employees respond to the ambassador model, where they take on multiple roles (reception, bar, concierge)?

- In what ways does this flexibility influence motivation, teamwork, and service quality?

- From your perspective, how do guests perceive the balance between self-service digital options and personal interaction with staff?

- What strategies do you use to ensure technology supports, rather than replaces, the human factor?

- How is staff training organized to prepare employees for both digital and service-oriented tasks?

- To what extent do digital HR tools (e-learning, apps) support employee professional development?

- How do employees express their satisfaction or concerns regarding this innovative HR model?

- In your opinion, does the ambassador model strengthen employees’ loyalty and long-term commitment to the company?

- Looking ahead, what improvements would you recommend in balancing technology, HR practices, and guest expectations?

Appendix C. Mapping of Guest Survey Items to Prior Literature

| # | Item wording (shortened) | Prior literature |

| 1 | App enabled me to manage most services | TAM [33]; UTAUT [34]; SST in hospitality [49,50,51] |

| 2 | Digitalization made stay more pleasant | ECT [54,55,56]; innovation [57] |

| 3 | Digital check-in/out saved me time | SST [49,50,51] |

| 4 | Digital promotions matched lifestyle | Experience Economy [16]; SDL [27]; personalization [46,53] |

| 5 | Digital solutions contribute to trust | Trust in IS/e-commerce [58,59,60,61,62] |

| 6 | Stay again because of digital benefits | Loyalty/relationship marketing [63,64,65] |

| 7 | Digitalization contributed to comfort | ECT [54,55,56]; innovation [57] |

| 8 | App suggested relevant content | SDL/resource integration [27,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42] |

| 9 | Transparency increased trust | Transparency → trust [60,61,62,63,64] |

| 10 | Hotel stands out due to tech | Differentiation & loyalty [65] |

| 11 | App intuitive & easy | TAM (PEOU) [33]; UTAUT (EE) [34] |

| 12 | Felt more relaxed thanks to digital | ECT [54,55,56] |

| 13 | Offers tailored to my needs | Personalization [46,53]; SDL [27] |

| 14 | Digital payments reliable & safe | E-commerce trust/security [58,59,60] |

| 15 | Recommend hotel due to digital | WOM/advocacy [63,64,65] |

| 16 | Balance between tech & human | Hybrid service models [43,44,45]; innovation [57] |

| 17 | Hotel cares through digital innovation | Innovation in hospitality [55,56,57] |

| 18 | Personalized content ↑ loyalty | Experience Economy [18]; SDL [27]; personalization [46,53] |

| 19 | Trust security of personal data | Trust in IS/e-commerce [58,59,60,61,62] |

| 20 | Choose hotel over others for tech | Differentiation & loyalty [63,64,65] |

| 21 | Hotel more efficient thanks to tech | TAM/UTAUT [33,34]; SST [49,50,51] |

| 22 | Personalized recs helped discovery | SDL [27,30,31,32]; personalization [46,53] |

| 23 | Innovative approaches → satisfaction | ECT [54,55,56]; innovation signaling [57] |

| 24 | Comfortable sharing more info | Trust/reciprocity [58,59,60,61,62] |

| 25 | Digitalization increases loyalty | Loyalty formation [63,64,65] |

| 26 | Reservation quick & simple | TAM (PU/PEOU) [33]; UTAUT [34] |

| 27 | Hotel innovative due to tech | Innovation signaling [57] |

| 28 | Prefer hotels with customized offers | Relationship marketing [63]; personalization [46,53] |

| 29 | Digital comm. confidential & secure | Trust/security [58,59,60,61,62] |

| 30 | Digital experiences → emotional bond | Affective commitment [63,64,65] |

| 31 | Digital solutions reduced reception wait | SST [49,50,51] |

| 32 | Digitalization improved experience | ECT [54,55,56]; SDL [27] |

| 33 | Digital marketing made me feel special | Experience Economy [18]; personalization [46,53] |

| 34 | Confident hotel uses my data responsibly | Trust & integrity [61,62] |

| 35 | Improved impression vs. competitors | Differentiation/innovation [57]; loyalty [63,64,65] |

| 36 | Digital tools reduced misunderstandings | SST [49,50,51] |

| 37 | All hotel info available digitally | TAM [33]; SST [49,50,51] |

| 38 | Digital solutions did not reduce quality | ECT [54]; service quality [55,56] |

References

- Busulwa, R.; Pickering, M.; Pathiranage, N.W. Readiness of hospitality and tourism curricula for digital transformation. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2024, 35, 100519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldawsari, R.; Buhalis, D.; Roushan, G. Immersive metaverse technologies for education and training in tourism and hospitality. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 37, 2716–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, C.; Zhang, H. Digital confusion: Comprehending the impact mechanisms of artificial intelligence-generated content and user-generated content on tourism decision making. Tour. Manag. 2026, 112, 105269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Moon, C.; Lee, K.; Su, X.; Hwang, J.; Kim, I. Exploring Smart Airports’ Information Service Technology for Sustainability: Integration of the Delphi and Kano Approaches. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, A.; Khanra, S. Mobile Payment Services in Hospitality and Tourism Sector: Technology Determinism, Social Constructivism, and Technology Ecosystem. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 29, 1204–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter Nira, R. AI-Driven Hyper-Personalization in Hospitality: Application, Present and Future Opportunities, Challenges, and Guest Trust Issues. Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci. 2025, 9, 5562–5573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavitha, K.; Shekhar, S.K. Mapping the Landscape of Digital Transformation and Digital Technologies in the Hotel Industry: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Analysis. Digit. Transform. Soc. 2025, 4, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, M.; Jayakar, K. Mobile Payments in Japan, South Korea and China: Cross-Border Convergence or Divergence of Business Models? Telecomm. Policy 2016, 40, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondego, D.; Gide, E. The Impact of Security, Service Quality, Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, Trust, and Price Value on Users’ Satisfaction in Cloud-Based Payment Systems in Australia: A PLS-SEM Analysis. J. Inf. Syst. Technol. Manag. 2024, 21, e202421004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifci, I.; Cam, B.; Demirbas, O.; Celikay, A. Deploying Blockchain in mobile public bazaars’ food supply chain within the tourism and hospitality industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2025, 16, 762–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Muñoz, S.; González-Sánchez, R.; González-Mendes, S.; García-Muiña, F. The role of blockchain-related technologies in transforming the tourism and hospitality industry: An overview and research guidelines. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 37, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, A.; Lee, M. Hospitality and tourism technology and organizational performance: An integrated framework of HTT business value and future research agenda. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 126, 104092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, A.S.; Wu, L.; Wang, P. Closing the gap: Advancing service management in the hospitality and tourism industry amidst the AI revolution. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2025, 62, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]