Abstract

This study investigates how perceptions of economic inequality are associated with confidence in elections through the mechanism of subjective class identification. Whereas much existing research relies on objective indicators of inequality, this analysis emphasizes the importance of subjective perceptions for understanding political trust. Using cross-national survey data from the International Social Survey Programme, the findings showed that individuals who perceive greater inequality are more likely to identify with a lower social class, and this self-placement is, in turn, associated with lower trust in electoral outcomes. These results highlight a pathway through which inequality influences democratic legitimacy, operating not only through structural conditions but also through how individuals interpret their relative social position. By identifying this association, this study contributes to debates on inequality and democratic resilience and calls for greater attention to the subjective dimensions of inequality in efforts to safeguard electoral legitimacy.

1. Introduction

Confidence in electoral integrity, a cornerstone of representative democracy, has weakened in many parts of the world. In the United States, false allegations of widespread fraud during the 2020 presidential election, promoted by President Donald Trump, eroded public trust in democratic institutions and culminated in the unprecedented attack on the Capitol [1]. The 2024 election revealed that these partisan suspicions had not diminished but instead intensified, further deepening fractures in democratic legitimacy [2]. This erosion of electoral trust is not confined to the American case. In other advanced democracies, skepticism toward electoral procedures has also become more visible, signaling a broader crisis of confidence in democratic governance [3,4,5,6,7].

Much of the existing scholarship has linked democratic backsliding to rising economic inequality [8,9,10,11]. These studies have highlighted important structural connections between inequality and the health of democratic institutions, often relying on objective measures such as income distributions or macroeconomic indicators. At the same time, a growing body of research demonstrates that political attitudes are also shaped by subjective perceptions of inequality, relative status, and fairness [12,13,14,15]. This work suggests that subjective perceptions can play a crucial role in shaping confidence in democratic procedures, which is a core element of democratic stability and, in some contexts, of democratic erosion.

This article concentrates on the individual-level mechanisms through which perceptions of inequality shape political trust. Specifically, it examines how perceptions of inequality influence subjective class identification and how, in turn, subjective class affects confidence in elections. Subjective class is treated not merely as a proxy for income or education but as a psychological orientation formed through processes of social comparison and relative deprivation. Individuals who perceive themselves as disadvantaged are therefore more likely to interpret political institutions as biased against them.

The analysis draws on cross-national data from the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP (using Stata, version 16)). The Social Inequality surveys from 2009 and 2019 are used to examine how perceived inequality influences subjective class across 32 countries. The Citizenship surveys from 2004 and 2014 are then used to assess how subjective class affects confidence in electoral outcomes across 40 countries. Together, these data allow for a broad comparative assessment of how inequality perceptions translate into political trust through the intermediary of class identity.

The results point to two key findings. First, individuals who perceive greater inequality are more likely to identify with a lower social class. Second, those who identify as lower class are significantly more likely to distrust election results, while those who identify as higher class express greater confidence. These associations hold across a wide range of models and country contexts, suggesting that the effect is systematic rather than confined to particular cases.

The findings carry implications for understanding the resilience of democracy under conditions of inequality. They indicate that inequality, as it is perceived and experienced by individuals, can undermine the symbolic foundations on which political legitimacy rests. Heightened perceptions of unfairness shape class identities that, in turn, make some citizens more likely to question the fairness of elections. This underscores the need to take the psychological dimensions of inequality seriously, both in scholarly analyses of democratic legitimacy and in policy efforts directed at strengthening trust in democratic institutions.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows. The next section reviews the literature on perceived inequality, subjective class, and political trust. The following section presents the data. The empirical results are then outlined in two steps: first, linking perceived inequality to subjective class, and then linking subjective class to electoral trust. The article concludes by discussing the broader implications of the findings and identifying directions for future research.

2. Perceptions of Inequality, Class and Trust in Elections

2.1. Understanding Perceived Inequality and Subjective Class Consciousness

Studies by Kuhn [16], Roth and Wohlfart [17], and Schmalor and Heine [18] suggest a convergence between objective measures of inequality and subjective perceptions of inequality. This convergence indicates that personal experiences significantly shape perceptions, establishing a link between measurable economic inequality and subjective assessments of one’s social standing. Such subjective assessments are critical for understanding how individuals perceive their social class, often shaped by comparisons with reference groups [12,19,20,21,22,23].

Understanding subjective class consciousness requires an exploration of its definition and its relationship with perceived inequality. Social class, as a multifaceted construct, profoundly influences psychological processes and behaviors [24,25]. Over time, social class informs distinct knowledge systems and behavioral patterns [26]. Objective class categorizations are typically based on measurable criteria such as income and education [27], while subjective class consciousness emerges from comparisons with Tajfeothers [28]. Subjective class consciousness is thus shaped by personal recognition and judgment rather than strictly by objective markers [20,29,30]. Consequently, alignment or divergence between objective and subjective class categorizations can result in varied political behaviors and outcomes, as highlighted by Eulau [31].

Tajfel’s [19] social comparison theory posits that individuals evaluate their status relative to peers, a process reinforced by the concept of relative deprivation [32,33,34]. Economic inequality accentuates class consciousness by intensifying perceived disparities within reference groups [16,17,35]. Those experiencing deprivation are more likely to perceive themselves as socially disadvantaged [30,36].

A body of research has linked perceived economic disparities to adverse psychological consequences, such as heightened status anxiety in unequal societies [37,38]. Status anxiety refers to a persistent concern with one’s social standing and a sense of relegation to a lower social position [39]. Accordingly, this study posits that individuals who are more concerned about inequality are more likely to perceive themselves as belonging to a lower social class, whereas those who are less concerned may not experience such perceptions.

2.2. Subjective Class and Trust in Elections

Subjective perceptions of class are an important determinant of political behavior and policy preferences [12,21,35,40,41]. In highly unequal societies, income or other objective indicators alone do not fully explain variation in political attitudes [42]. Examining the role of subjective class consciousness is therefore essential for understanding how individuals evaluate the legitimacy of political institutions.

The link between subjective class and electoral trust can be understood through the experience of deprivation. Goffman [43] argued that trust is shaped by social experiences, and subsequent research has shown that individuals who perceive themselves as marginalized often develop psychological defensiveness and lower levels of trust [44,45]. Those identifying as lower class frequently report feelings of relative deprivation, lack of recognition, and diminished autonomy [30,36,46]. These experiences foster perceptions of exclusion and bias that can easily extend to evaluations of political institutions. In this way, subjective class influences whether individuals view elections as credible mechanisms for representation or as processes that reproduce existing inequalities.

The relationship between deprivation and trust also operates through generalized social trust. Generalized trust, the belief that others and institutions can be relied upon, facilitates social cooperation and sustains social capital [47,48,49]. High levels of trust support adaptive orientations, encouraging individuals to interpret political processes, including elections, as fair and legitimate [50,51,52]. Conversely, low social trust, often rooted in perceptions of deprivation or exclusion, weakens social bonds and erodes confidence in both interpersonal and political relationships [53]. Political trust, which builds on these broader orientations, is directly connected to evaluations of government performance and electoral integrity [54].

Building on this scholarship, the present study posits that subjective class perceptions help shape electoral trust through their influence on social and political orientations. Individuals who see themselves as relatively advantaged are more likely to extend trust to political institutions, including elections, and to accept outcomes as legitimate. By contrast, those who experience themselves as disadvantaged are more likely to view elections with suspicion, interpreting them as biased or rigged.

3. Data

This study uses data from the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP), a long-running cross-national survey that systematically measures social and political attitudes across diverse contexts. Two ISSP modules are central to the analysis. The Social Inequality surveys from 2009 and 2019 provide the basis for examining how perceptions of income inequality are associated with subjective class identification. These waves cover 32 countries, including Argentina, Austria, Australia, Belgium, Bulgaria, Switzerland, Chile, the Czech Republic, Germany, Denmark, Estonia, Spain, Finland, France, the United Kingdom, Croatia, Israel, Iceland, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Lithuania, Latvia, Norway, New Zealand, the Philippines, Poland, Sweden, Slovenia, Slovakia, the United States, and South Africa.

The Citizenship modules from 2004 and 2014 cover a wide range of countries, including Austria, Australia, Belgium, Bulgaria, Brazil, Canada, Switzerland, Chile, the Czech Republic, Germany, Denmark, Spain, Finland, France, Georgia, Croatia, Hungary, Ireland, India, Iceland, Japan, South Korea, Lithuania, Latvia, Mexico, The Netherlands, Norway, New Zealand, the Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Sweden, Slovenia, Slovakia, Turkey, the United States, Uruguay, Venezuela, and South Africa.

Across all waves, country-level sample sizes range from roughly 900 to 2500 respondents, with nationally representative samples drawn using stratified or multistage probability designs. For consistency, the analysis is restricted to respondents aged 18 and older who provided valid responses to the relevant questions. Missing data on the main variables of interest were handled through listwise deletion. Because the proportion of missing cases is small (less than 5 percent for the key variables, including perceived inequality, subjective class and trust in elections), this procedure does not materially affect the results. The specific variables, coding decisions, and analytical techniques are described in the subsections that follow.

4. Empirical Assessments

This section presents two sequential analyses to test the core argument. The first examines how perceived inequality shapes subjective class consciousness; the second investigates how subjective class consciousness affects trust in voting. Together, these analyses offer empirical evidence linking perceptions of inequality to electoral trust through the intermediary of class perception.

4.1. Perceived Income Inequality and Subjective Class Consciousness

This study conducts an individual-level analysis using data from the 2009 and 2019 ISSP to examine the effect of perceived income inequality on subjective class consciousness across 32 countries. The key explanatory variable, perceived income inequality, is measured on a scale from 1 to 5, while the dependent variable, subjective class, ranges from 1 (lowest class) to 10 (highest class). Two alternative dichotomous variables, High Class and Low Class, are also employed: High Class is coded as 1 if subjective class is perceived between 8 and 10, and Low Class as 1 if perceived between 1 and 3.

The analysis controls for objective socioeconomic factors, including income (divided into four country-specific deciles), education (ordinal scale from 1 to 5), and occupation (categorized into high-skilled and low-skilled based on ISCO classifications). Additional controls include sex, age, marital status, religiosity, urbanization, and political orientation. Country and year fixed effects are also included to account for unobserved variables (see Supplementary Materials for details).

Table 1 presents the regression results linking perceived income inequality to subjective class identification. The ordered logistic results indicate that higher levels of perceived inequality are significantly related to lower subjective class placement. The estimated coefficient for perceived inequality is −0.073 (p = 0.002), which means that, controlling for income, education, occupation, and other covariates, individuals who perceive greater inequality are consistently more likely to place themselves lower on the social ladder.

Table 1.

Perceived income inequality and subjective class.

The results for the dichotomous class outcomes reinforce this pattern. In the logistic regression for high class identification, perceived inequality carries a negative and significant coefficient (−0.096, p = 0.013), indicating that rising perceptions of inequality reduce the probability of placing oneself in the upper categories of the class scale. By contrast, in the model predicting low class identification, the coefficient for perceived inequality is positive and significant (0.057, p = 0.043), showing that greater perceived inequality increases the likelihood of identifying with the lowest class categories.

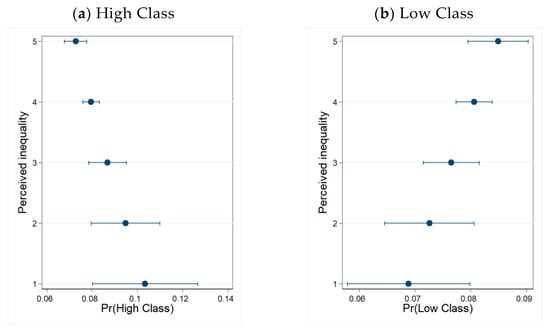

Figure 1, based on Models (2) and (3) in Table 1, illustrates the substantive magnitude of these effects. The predicted probability of identifying as high class decreases from 0.10 to 0.07, while the probability of identifying as low class rises from 0.06 to 0.08. Although the changes appear modest, they are consistent across specifications and statistically reliable, underscoring the role of perceived inequality in shaping subjective class identification.

Figure 1.

Predicted effects of Perceived income inequality.

Overall, these results provide evidence that perceptions of income inequality push individuals toward lower subjective class positions. This finding is central for understanding how inequality perceptions influence class consciousness and, as subsequent analyses demonstrate, how they ultimately affect trust in electoral outcomes.

4.2. Subjective Class Consciousness and Trust in Voting

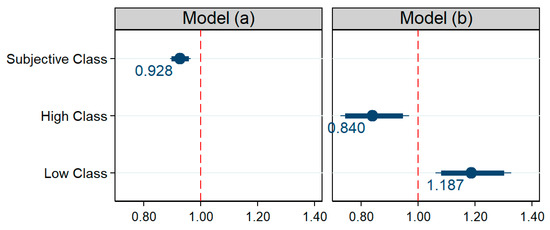

The preceding analysis examined how perceptions of income inequality shape subjective class identification. Building on this, the next step tests the central hypothesis by analyzing the effect of subjective class consciousness on trust in election results, drawing on data from the 2004 and 2014 ISSP Citizenship modules covering 40 countries. The dependent variable, distrust in elections, is measured by responses to the question: “Thinking of the last national election, how honest were the counting and reporting of votes?” Responses range from 1 (highest trust) to 5 (lowest trust), with higher values reflecting greater distrust in electoral processes. The primary explanatory variables are subjective class, high class, and low class, with control variables consistent with prior analyses (see Supplementary Materials). Model (a) includes a subjective class, while Model (b) incorporates both high and low classes. Country and year fixed effects are also estimated. Figure 2 presents the results of both models.

Figure 2.

Subjective class and trust in voting (odds ratio). Note: Odds ratios from ordered logistic regressions (N = 36,360). Model (a) includes a subjective class measured on a 1–10 self-placement scale. Model (b) distinguishes high class (scores 8–10) and low class (scores 1–3). The dependent variable is distrust in elections, coded from 1 (highest trust) to 5 (lowest trust). Controls include income, education, occupation, age, sex, marital status, religiosity, urban residence, and political orientation, with country and year fixed effects. Odds ratios below 1 indicate greater trust, while those above 1 indicate greater distrust. Full results are reported in Table S8 in the Supplementary Materials.

In Model (a), the negative coefficients for subjective class indicate that a higher subjective class is associated with greater trust in election results. Model (b), which includes both high and low classes, reinforces this finding. The subjective class variables are statistically significant at the five percent level or lower, confirming that subjective social class is a significant predictor of trust in election outcomes. In sum, individuals who identify as high class are more likely to trust election results, while those identifying as low class are more prone to distrust them. These findings robustly support the hypothesis and are consistent across models.

In Model (a), the odds ratio for subjective class is 0.928, indicating that each unit increase in subjective class reduces the odds of electoral distrust by approximately 7.2%. In Model (b), being classified as high class decreases the odds of distrust by 16% (odds ratio = 0.840), while being classified as low class increases it by 18.7% (odds ratio = 1.187). These results support the hypothesis that individuals identifying as higher class are more likely to trust election outcomes, whereas those identifying as lower class exhibit greater skepticism.

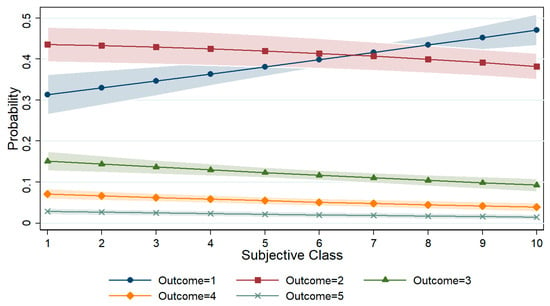

Figure 3, based on Model (a), illustrates the effect of subjective class on the probability of various trust levels in voting outcomes. The x-axis represents the subjective class, and the y-axis represents the probability of five outcomes, ranging from highly trust (=1) to highly distrust (=5). As subjective class increases from 1 to 10, the probability of highly trusting the voting process rises from 31.34% to 47.10%. Conversely, the probability of trusting declines from 43.54% to 38.22%, being neutral drops from 15.11% to 9.28%, distrusting falls from 7.12% to 3.89%, and highly distrusting decreases from 2.89% to 1.50%. These findings demonstrate that higher subjective class is strongly associated with greater trust in the electoral process.

Figure 3.

Effect of Subjective Class on Trust in Voting Outcomes. Note: Based on Model (a), the figure shows how subjective class affects the likelihood of reporting different levels of trust in election results. The x-axis represents self-placement on a 1–10 class scale, and the y-axis shows predicted probabilities for five outcomes: highly trust (=1), trust (=2), neutral (=3), distrust (=4), and highly distrust (=5). As subjective class increases from 1 to 10, the probability of highly trusting elections rises from 31.34 percent to 47.10 percent, while the probabilities of trust, neutrality, distrust, and high distrust fall from 43.54 to 38.22 percent, 15.11 to 9.28 percent, 7.12 to 3.89 percent, and 2.89 to 1.50 percent, respectively. The results demonstrate a clear pattern in which higher subjective class is linked to greater electoral confidence and lower subjective class to greater skepticism.

4.3. Robustness Checks

Several robustness checks were conducted to assess the stability of the results. First, multilevel models that accounted for within-country variation confirmed the main findings, indicating that the associations are not artifacts of country-level clustering (Tables S9 and S10). Second, analyses limited to established democracies with a V-Dem score of 7 or higher, including the United States, United Kingdom, and Germany, produced consistent results (Tables S11 and S12), suggesting that the observed patterns are not confined to newer or less consolidated democracies. Third, a jackknife procedure excluding one country at a time (Figure S1) showed that no single case exerted undue influence on the overall estimates. Fourth, models incorporating objective indicators such as income, occupation, and education yielded similar patterns: individuals with higher income, professional occupations, or higher levels of education reported greater confidence in electoral processes, while those with lower income or lower levels of education expressed greater distrust (Tables S8 and S10). Finally, multicollinearity was evaluated using variance inflation factors (VIF). In the analysis of perceived inequality and subjective class, VIF values for the substantive predictors ranged from 1.08 to 1.71; in the analysis of subjective class and electoral trust, the range was 1.09 to 1.68. Both sets of values fall well below conventional thresholds of concern (typically 5, and more conservatively 10), indicating that multicollinearity is not a problem in either analysis.

5. Conclusions and Implications

This study investigated how perceptions of inequality and subjective class identification are linked to confidence in electoral processes. By focusing on perceptions rather than purely structural indicators, it emphasizes that class is not only an economic position but also a subjective orientation grounded in social comparison and relative standing. Elections, despite being institutionalized procedures of aggregating votes, also rely on being widely regarded as legitimate. The results suggest that individuals who place themselves higher on the social ladder are more likely to trust election outcomes, whereas those identifying with lower classes are more inclined to express skepticism.

These results should be interpreted with caution. The analysis relies on cross-sectional survey data, which do not produce firm conclusions about causal direction. It remains uncertain whether stronger perceptions of inequality lead individuals to identify with a lower social class or whether identifying as lower class heightens sensitivity to inequality. Moreover, because the ISSP modules on inequality and citizenship were fielded in different years and country samples, the full pathway cannot be estimated within a single unified dataset. What this study demonstrates, therefore, is that these variables are systematically associated across a wide range of national contexts, rather than providing evidence of a causal sequence.

In addition, while objective factors such as income, education, and occupation were included in the models, the interaction between objective and subjective measures of class could not be examined in full detail. Future research should investigate how heterogeneity across socioeconomic status, education, or ideological orientation may condition the effects identified here, since these subgroups may experience and interpret inequality in different ways. A more systematic comparison of how objective and subjective class interact in shaping electoral trust would be especially valuable. Likewise, the potential role of institutional settings, such as electoral systems, patterns of party competition, and levels of electoral integrity, deserves further examination, as comparative scholarship suggests that these contexts may amplify or dampen the influence of inequality perceptions.

Within these limits, the analysis points to several noteworthy patterns. First, both objective and subjective dimensions of class are relevant for electoral trust, but subjective class provides a distinctive pathway linking inequality perceptions to democratic attitudes. Second, perceptions of inequality appear to shape how individuals view their place in society, and these perceptions, once internalized, can become a channel through which doubts about elections gain credibility. Third, the dynamics of class-based skepticism are not confined to individual dispositions. They may be reinforced in social interactions, producing collective narratives of electoral fraud or bias. The prominence of such narratives in countries like the United States, where inequality has been politically salient, illustrates how economic perceptions can feed into broader disputes over electoral legitimacy.

The broader implication of this analysis is that inequality generates risks that extend beyond the distribution of resources. When confidence in elections becomes stratified along class lines, societies risk dividing into groups that accept elections as legitimate and groups that view them with suspicion. Such a divide undermines the representative basis of democracy and complicates effective governance. The findings, therefore, underscore the importance of addressing inequality not only to reduce material hardship but also to sustain the institutional trust on which democratic legitimacy ultimately rests.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/world6040132/s1, Table S1: Survey information; Table S2: Dependent variables; Table S3: Explanatory variables for ISSP; Table S4: Descriptive statistics for analysis 1; Table S5: Descriptive statistics for analysis 2; Table S6: List of countries for analysis; Table S7: Perceived income inequality and subjective class, full results; Table S8: Subjective class and the trust in voting, full results; Table S9: Perceived in-come inequality and subjective class, multilevel estimations; Table S10: Subjective class and the trust in voting, multilevel estimations; Table S11: Perceived income inequality and subjective class (Advanced democracies); Table S12: Subjective class and the trust in voting (Advanced democra-cies); Figure S1: Jackknife analysis.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data and code are shared via Harvard Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/89DBEU).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Cabral, S. Capitol Riots: Did Trump’s Words at Rally Incite Violence? BBC, 14 February 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Linegar, M.; Alvarez, R.M. American Views about Election Fraud in 2024. Front. Polit. Sci. 2024, 6, 1493897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, S. Electoral Institutions and Popular Confidence in Electoral Processes: A Cross-National Analysis. Elect. Stud. 2008, 27, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauk, M. Electoral Integrity Matters: How Electoral Process Conditions the Relationship between Political Losing and Political Trust. Qual. Quant. 2022, 56, 1709–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, P. Big Little Election Lies: Cynical and Credulous Evaluations of Electoral Fraud. Parliam. Aff. 2024, 77, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Chung, C.J.; Kim, D. Semantic Networks of Election Fraud: Comparing the Twitter Discourses of the U.S. and Korean Presidential Elections. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S. Democracy at a Crossroads: Polarization, Authoritarian Echoes, and the Struggle for Legitimacy in South Korea. Democratization 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Robinson, J.A. Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Haggard, S.; Kaufman, R.R. Inequality and Regime Change: Democratic Transitions and the Stability of Democratic Rule. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2012, 106, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheve, K.; Stasavage, D. Wealth Inequality and Democracy. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2017, 20, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S. Exploring the Nexus of House Price, Income, Homeownership Types, and Electoral Democracy: Heterogeneous Effects of Housing Wealth on Political Outcomes in OECD Countries. Compet. Change 2025, 29, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown-Iannuzzi, J.L.; Lundberg, K.B.; McKee, S.E. Economic Inequality and Socioeconomic Ranking Inform Attitudes toward Redistribution. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 96, 104180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S. The Erosion of Democracy in an Age of Wealth Inequality: Unravelling the Impact of Subjective Socioeconomic Stratification. Br. J. Politics Int. Relat. 2025, 27, 1103–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Kwon, H. Inequality, Social Context, and Income Bias in Voting: Evidence from South Korea. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2023, 35, edad018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S. The Strongman Phenomenon: Unpacking the Role of Subjective Class. Polit Groups Identities 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, A. The Individual (Mis-)Perception of Wage Inequality: Measurement, Correlates and Implications. Empir. Econ. 2020, 59, 2039–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, C.; Wohlfart, J. Experienced Inequality and Preferences for Redistribution. J. Public Econ. 2018, 167, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalor, A.; Heine, S.J. The Construct of Subjective Economic Inequality. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2021, 13, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Human Groups and Social Categories: Studies in Social Psychology; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Jackman, M.R.; Jackman, R.W. An Interpretation of the Relation between Objective and Subjective Social Status. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1973, 38, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condon, M.; Wichowsky, A. Inequality in the Social Mind: Social Comparison and Support for Redistribution. J. Polit. 2020, 82, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, J.; Evans, M.D.R. Class and Class Conflict in Six Western Nations. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1995, 60, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Han, S. Perceptions of Inequality and Loneliness as Drivers of Social Unraveling: Evidence from South Korea. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, M.W.; Piff, P.K.; Keltner, D. Social Class, Sense of Control, and Social Explanation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 992–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrove, J.M.; Cole, E.R. Privileging Class: Toward a Critical Psychology of Social Class in the Context of Education. J. Social. Issues 2003, 59, 677–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, M.W.; Stephens, N.M. A Road Map for an Emerging Psychology of Social Class. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2012, 6, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingshead, A.B. Four Factor Index of Social Status; Department of Sociology, Yale University: New Haven, CT, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Weakliem, D.L.; Adams, J. What Do We Mean by “Class Politics”? Polit. Soc. 2011, 39, 475–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackman, M.R.; Jackman, R.W. Class Awareness in the United States; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, S. Class and Comparison: Subjective Social Location and Lay Experiences of Constraint and Mobility. Br. J. Sociol. 2015, 66, 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eulau, H. Identification with Class and Political Perspective. J. Polit. 1956, 18, 232–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.A. A Formal Interpretation of the Theory of Relative Deprivation. Sociometry 1959, 22, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.K.; Kitt, A.S. Contributions to the Theory of Reference Group Behaviour; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Runciman, W.G. Relative Deprivation and Social Justice: A Study of Attitudes to Social Inequality in Twentieth-Century England; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, B.J.; Johnston, C.D.; Lown, P.L. False Consciousness or Class Awareness? Local Income Inequality, Personal Economic Position, and Belief in American Meritocracy. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 2015, 59, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neckerman, K.M.; Torche, F. Inequality: Causes and Consequences. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2007, 33, 335–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layte, R.; Whelan, C.T. Who Feels Inferior? A Test of the Status Anxiety Hypothesis of Social Inequalities in Health. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2014, 30, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Bailón, R.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, Á.; García-Sánchez, E.; Petkanopoulou, K.; Willis, G.B. Inequality Is in the Air: Contextual Psychosocial Effects of Power and Social Class. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 33, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Botton, A. Status Anxiety; Vintage: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Côté, S.; House, J.; Willer, R. High Economic Inequality Leads Higher-Income Individuals to Be Less Generous. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 15838–15843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thal, A. Class Isolation and Affluent Americans’ Perception of Social Conditions. Polit. Behav. 2017, 39, 401–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, M.L.; Birchfield, V. Economic Development, Income Inequality, and Preferences for Redistribution. Int. Stud. Q. 2010, 54, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Stigma; Simon & Schuster Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, P.J. Low-Status Compensation: A Theory for Understanding the Role of Status in Cultures of Honor. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, P.J. The Role of Stigma in Understanding Ethnicity Differences in Authoritarianism. Polit. Psychol. 2011, 32, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Lee-Geiller, S. The Ripple Effects of Time Inequality on Perceived Autonomy and Social Trust: Evidence from South Korea and OECD Democracies. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2025, 37, edaf029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Foundations of Social Theory; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D.; Leonardi, R.; Nonetti, R.Y. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, F. Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Alesina, A.; La Ferrara, E. Who Trusts Others? J. Public. Econ. 2002, 85, 207–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslaner, E.M. The Moral Foundations of Trust; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hamamura, T. Social Class Predicts Generalized Trust But Only in Wealthy Societies. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2012, 43, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, M.J.; Henry, P.J. Psychological Defensiveness as a Mechanism Explaining the Relationship Between Low Socioeconomic Status and Religiosity. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 2012, 22, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, D. Trust in Government and the American Public’s Responsiveness to Rising Inequality. Polit. Res. Q. 2020, 73, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).