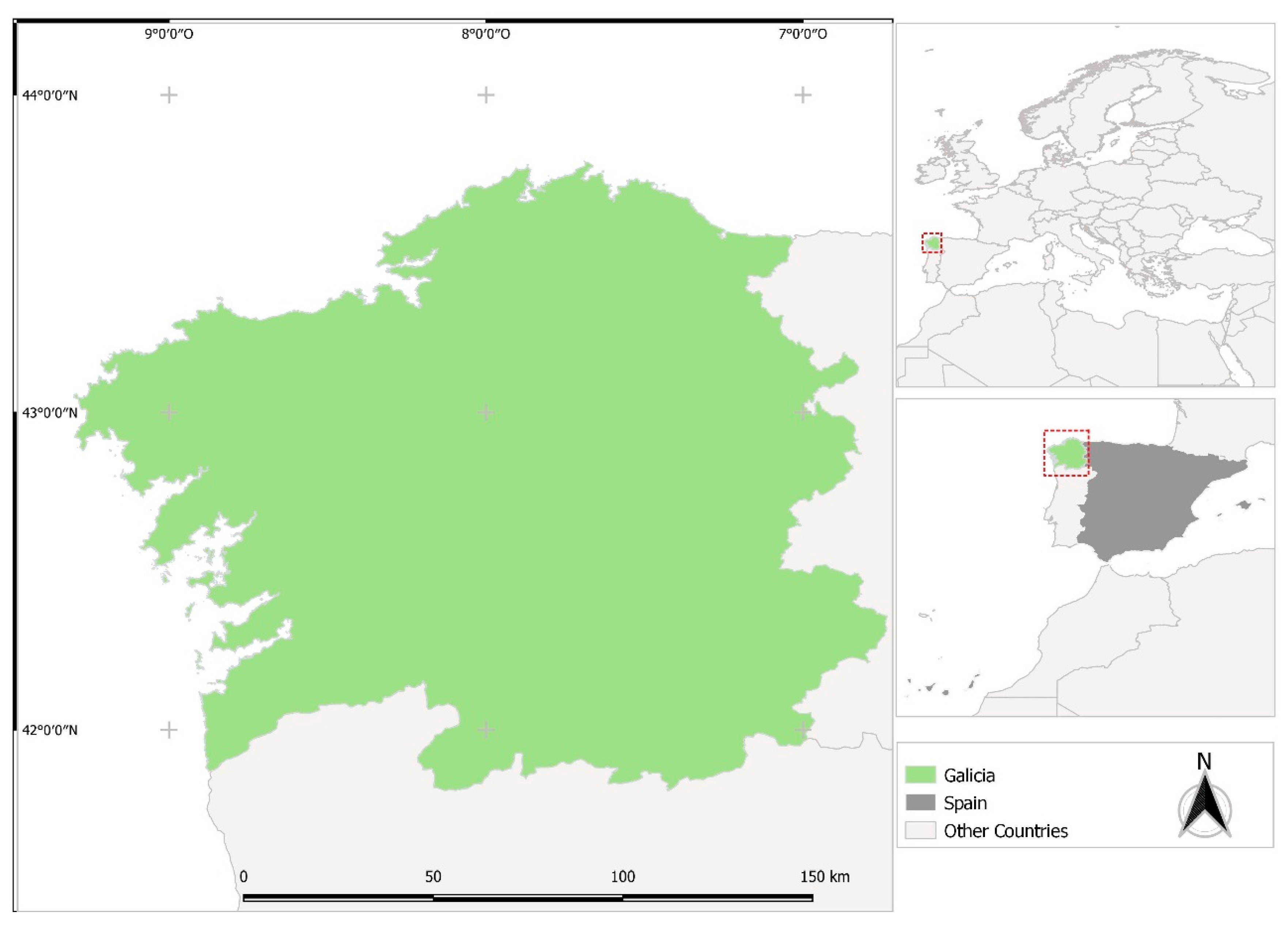

Gastronomic Tourism and Digital Place Marketing: Google Trends Evidence from Galicia (Spain)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Concept: Gastronomic Tourism and Digital Territorial Marketing

3. Methodology

- Selection of terms

- Construction of queries

- Configuration of the platform

- Export approach

- Pre-processing

- Analysis

- Visualisation.

4. Problem Description and the Territorial Marketing Strategies in Galicia as a Global Example: Main Digital Tools

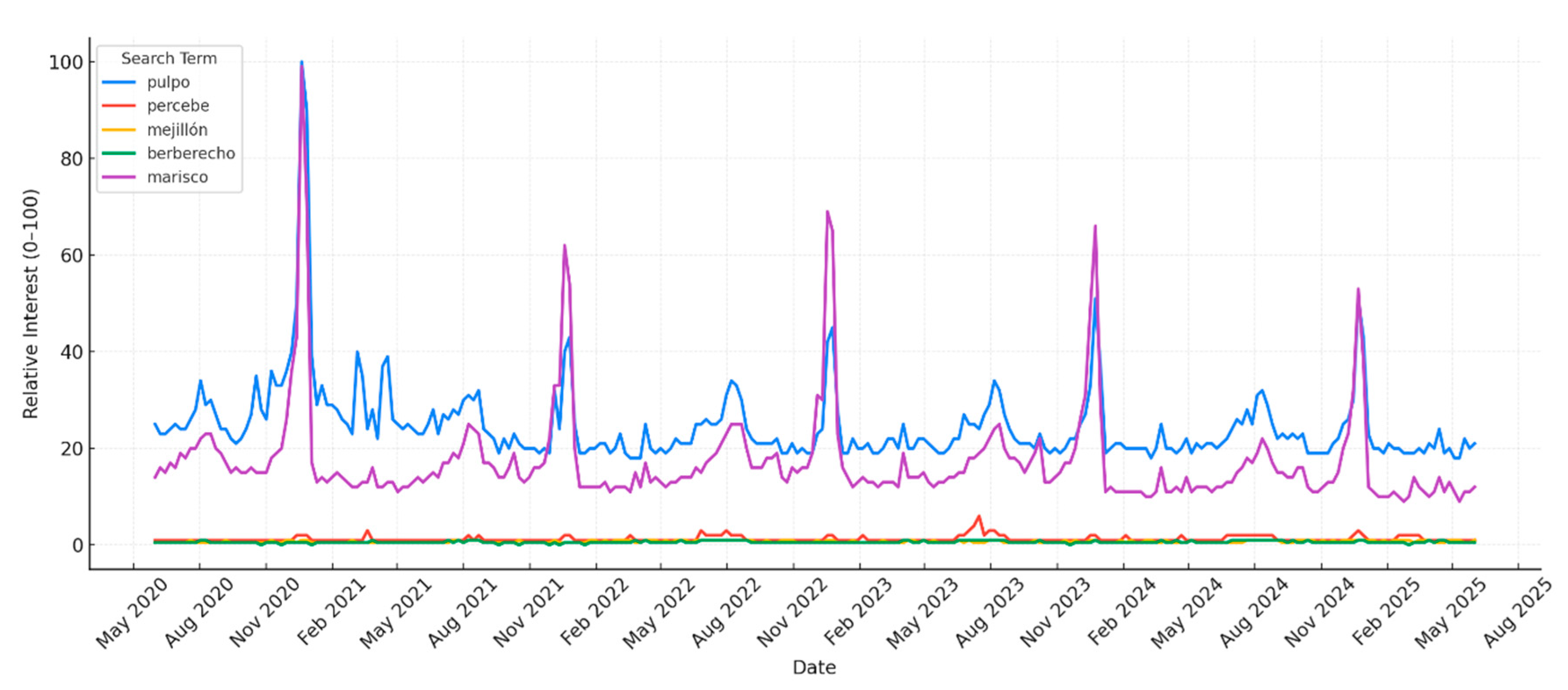

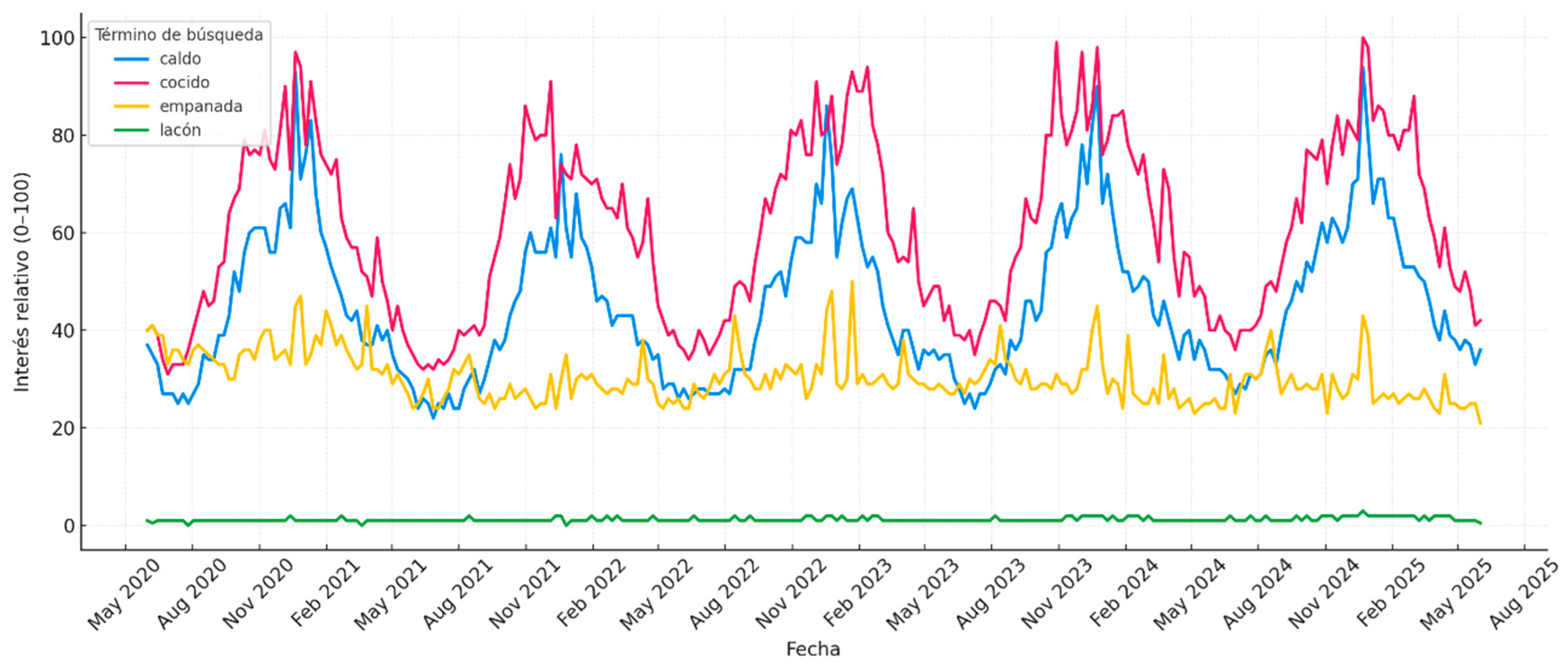

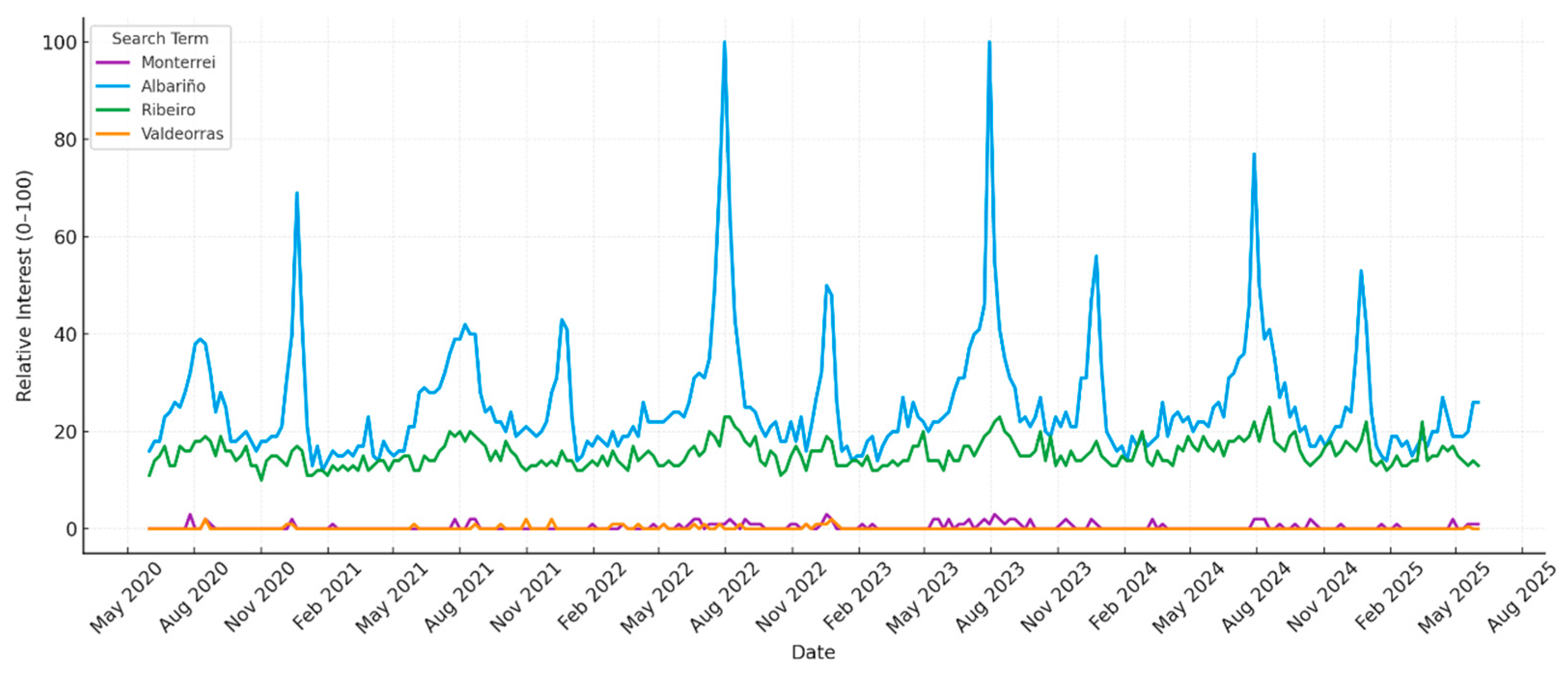

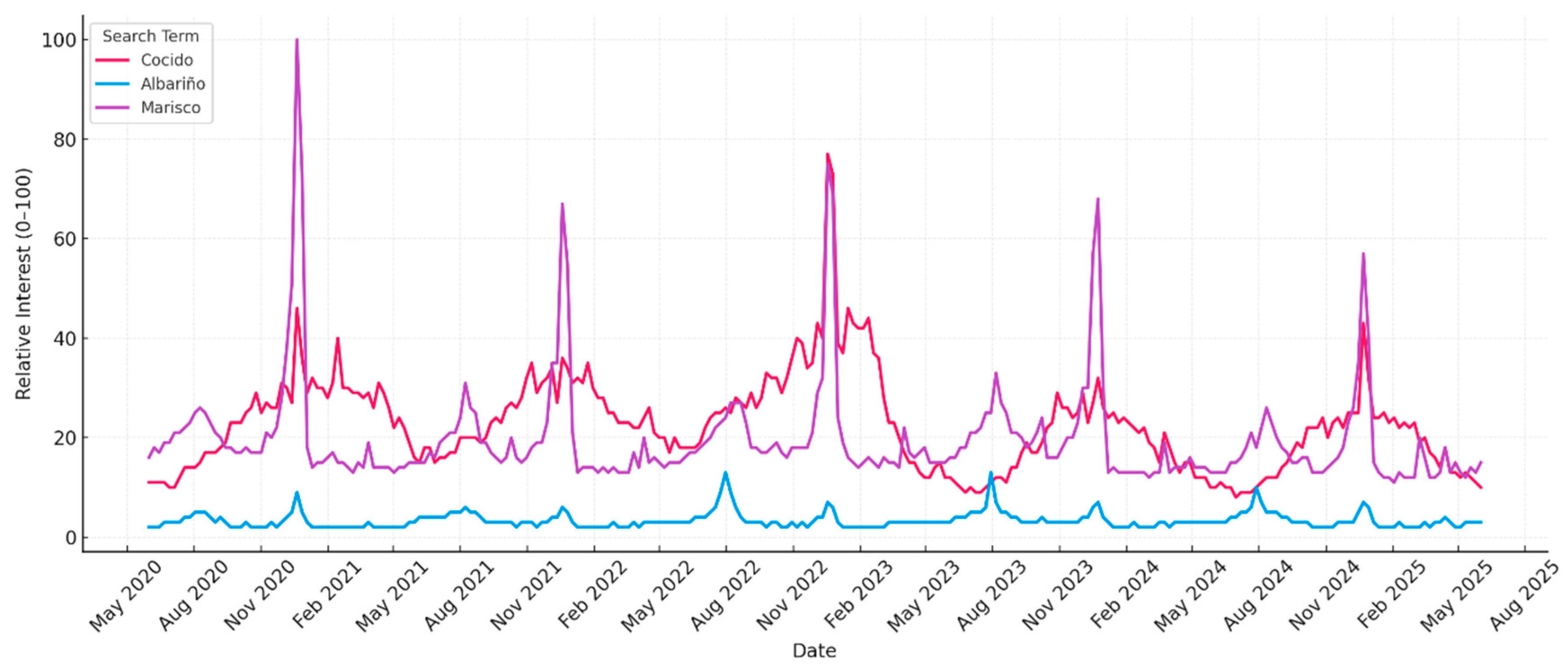

5. Case Study: Analysis of Gastronomic Tourism Terms Using Search Engine Tools

6. Results

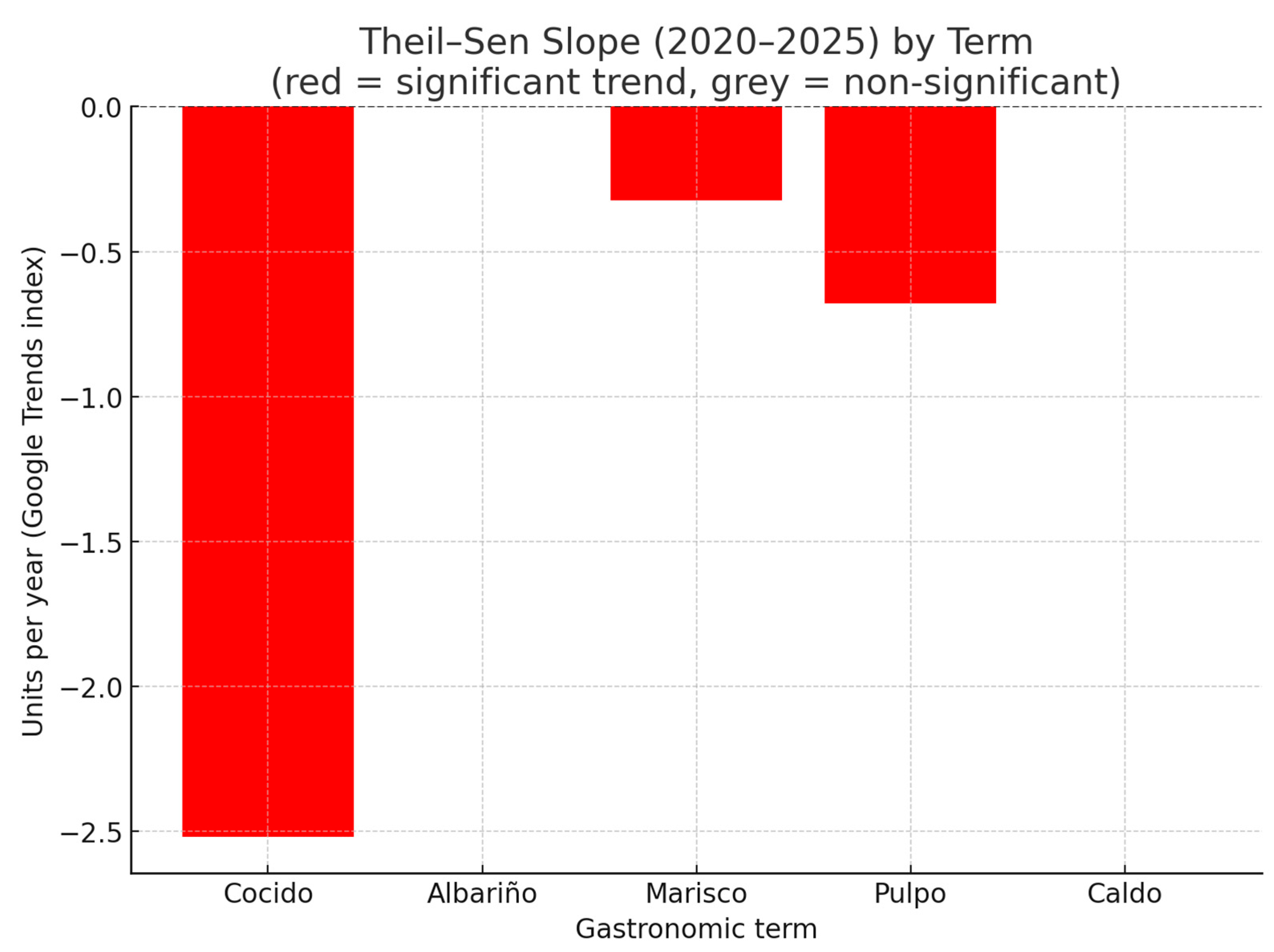

- Cocido: negative slope (≈−2.52 units/year), strong and significant downward trend (p < 0.001).

- Albariño: slope ≈ 0, but with a slight and significant positive trend (p ≈ 0.006).

- Marisco: negative slope (≈−0.32 units/year), slight but significant downward trend (p ≈ 0.013).

- Pulpo: negative slope (≈−0.68 units/year), clear and significant downward trend (p < 0.001).

- Caldo: slope ≈ 0, no significant trend (p ≈ 0.94).

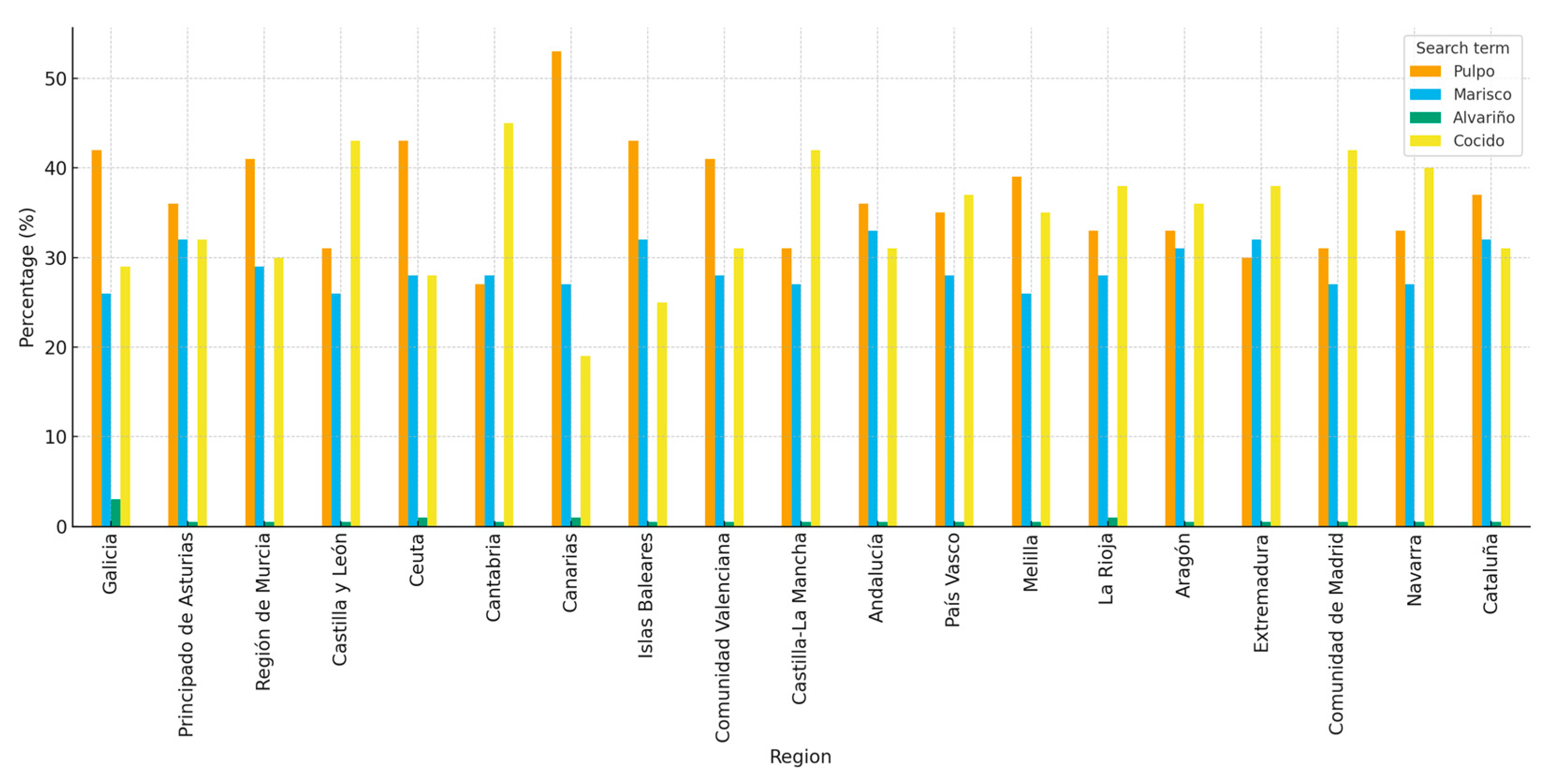

- Cocido reaches very high percentages in inland regions such as Castile and León, where it even surpasses the other terms.

- Pulpo continues to stand out in Galicia, Asturias and, surprisingly, in Murcia and Ceuta.

- Marisco maintains a more balanced profile in most regions.

- Alvariño continues to be a very localised term, concentrated almost exclusively in Galicia.

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seyitoğlu, F.; Stanislav, I. A conceptual study of the strategic role of gastronomy in tourism destinations. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2020, 21, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Londoño, M.P. Gastronomic Tourism and Local Development in Catalonia: The Supply and Marketing of Food Products. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2013. Available online: https://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/handle/2445/46606 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- UNWTO (World Tourism Organization). Global Report on Food Tourism; UN-WTO: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Armesto, X.A.; Gómez, B. Quality agri-food products, tourism and local development: The case of Priorat. Cuad. Geogr. 2004, 34, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Aydın, A. The strategic process of integrating gastronomy and tourism: The case of Cappadocia. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2019, 18, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.C. Food tourism reviewed. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.; Park, E.; Kim, S.; Yeoman, I. What is food tourism? Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.N.S.; Getz, D.; Dolincar, S. Food tourism sub-segments: A da-ta-driven analysis. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.K. (Ed.) Marketing gastronomic tourism experiences. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism Experience Management and Marketing; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 322–335. [Google Scholar]

- Duman, H.; Avcıkurt, C. Evaluation of local dishes as an intangible cultural heritage value in terms of gastronomy tourism: The case of Ayvalık. J. Gastron. Hosp. Travel 2023, 6, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Beltrán, J.; López Guzmán, T.; González Santa-Cruz, F. Gastronomy and tourism: Profile and motivation of international tourism in the city of Córdoba, Spain. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2016, 14, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Eguez, C.G.; Villalva-Guevara, M.R.; Villalva-Guevara, S.C.; Romero-Machado, E.R. Turismo gastronómico en Riobamba, Ecuador: Un análisis del perfil del visitante. Polo Conoc. 2024, 9, 747–773. Available online: https://polodelconocimiento.com/ojs/index.php/es/article/download/7723/pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Arteaga Sánchez, R.; Maldonado López, B.; Suárez Redondo, E.; Valverde-Roda, J.M. Turismo gastronómico: El impacto de TikTok e Instagram sobre el sector restaurante saludable en España. In Nuevas Dimensiones de Cambio en el Panorama Turístico Actual. Melilla as an Emerging Destination; Marmolejo Martín, J.A., Moral Cuadra, S., Eds.; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2025; pp. 475–485. [Google Scholar]

- Lois González, R.C.; Martíns Rodal, B.; Patiño Romarís, C.A. Gastronomic pleasure in an Atlantic Spanish tourist destination: The region of Galicia. In Sensory Tourism: Senses and Sensescapes Encompassing Tourism Destinations; Jenkins, I.S., Bristow, R.S., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2024; pp. 131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez, N.; Mullo, E.; Cajo, M. El turismo gastronómico como estrategia para el desarrollo sostenible. Exprint Investig. 2025, 4, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos Silva, F.; Ramazanova, M.; Vaz Freitas, I. Safeguarding traditional Por-tuguese gastronomy as an intangible cultural heritage through tourism: The case of North of Portugal. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusté-Forné, F. Gastronomy in tourism marketing. An. Bras. Estud. Turísticos 2017, 7, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico Jerez, M. Tourism marketing of the Autonomous Communities of Spain to promote gastronomy as part of their destination branding. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2023, 32, 100727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Sharples, L. The consumption of experiences or the experience of consumption? An introduction to the tourism of taste. In Food Tourism Around the World; Hall, C.M., Sharples, L., Mitchell, R., Macionis, N., Cambourne, B., Eds.; But-terworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hillel, D.; Belhassen, Y.; Shani, A. What makes a gastronomic destination at-tractive? Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán Vázquez de la Torre, M.G. Las empresas alimentarias, nuevo motor del turismo industrial en la provincia de Córdoba: Análisis del perfil del turista. ROTUR. Rev. Ocio Tur. 2011, 4, 89–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgalicia. Plan de Enogastronomía de Galicia. Executive Summary; Xunta de Galicia: Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2012. Available online: http://www.turgalicia.es/docs/mdaw/mtuz/~edisp/turga153270.pdf?langId=es_ES (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Rinaldi, C. Food and gastronomy for sustainable place development: A multi-disciplinary analysis of different theoretical approaches. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Rand, G.E.; Heath, E. Towards a framework for food tourism as an element of destination marketing. Curr. Issues Tour. 2006, 9, 206–234. [Google Scholar]

- Sio, K.P.; Fraser, B.; Fredline, L. A contemporary systematic literature review of gastronomy tourism and destination image. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 49, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basulto Gallegos, O.F. Relevance of social imaginaries in the construction of tourism territorial value: Analysis of a comparative case study. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2020, 29, 932–957. [Google Scholar]

- Patiño Romarís, C.A.; Martins Rodal, B.; Lois González, R.C. Global touristifi-cation: Tourism reversal, management, recrectification or decrectification? Gastronomic tourism as a diversification strategy of mature coastal destinations. In Diversity, Dy-namics and Responses to the Global Change; Comité Español de la UGI, Ed.; Centro Nacional de Información Geográfica: Madrid, Spain, 2024; pp. 182–196. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, T.; Hubbard, P. The entrepreneurial city: New urban politics, new urban geographies. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1996, 20, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Andreasen, A.R. Strategic Marketing for Nonprofit Organizations, 6th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos Vecino, N.; Fernández Portillo, A.; Almodóvar González, M. El uso de estrategias de marketing digital para la promoción turística de las comunidades autónomas españolas. Int. J. Commun. Res. aDResearch ESIC 2020, 21, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz Martínez, N.; Cervantes Blanco, M. Marketing de ciudades y “place branding”. J. Fac. Econ. Bus. 2010, 123–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bigné Alcañiz, J.E.; Font Aulet, X.; Andreu Simó, L. Marketing of Tourist Destinations: Analysis and Development Strategies; ESIC Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Elbe, J.; Hallen, L.; Axelsson, B. The destination-management organisation and the integrative destination-marketing process. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Varian, H. Predicting the Present with Google Trends. Econ. Rec. 2012, 88, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuti, S.V.; Wayda, B.; Ranasinghe, I.; Wang, S.; Dreyer, R.P.; Chen, S.I.; Murugiah, K. The Use of Google Trends in Health Care Research: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölzl, J.; Keusch, F.; Sajons, C. The (Mis)Use of Google Trends Data in the Social Sciences—A Systematic Review, Critique and Recommendations. Soc. Sci. Res. 2025, 126, 103099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrián, E.; Domenech, J. Addressing Google Trends Inconsistencies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 198, 122965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, R.; White, R.W.; Horvitz, E. Calibration of Google Trends Time Series. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.13861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Ismagilova, E.; Hughes, D.L.; Carlson, J.; Filieri, R.; Jacobson, J.; Jain, V.; Karjaluoto, H.; Kefi, H.; Krishen, A.; et al. Setting the future of digital and social media marketing research: Perspectives and research propositions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 59, 102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borst, T.; Limani, F. Patterns for searching data on the web across different research communities. LIBER Q. 2020, 30, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gajanova, L.; Moravcikova, D. The use of demographic and psychographic segmentation to creating marketing strategy of brand loyalty. Sci. Ann. Econ. Bus. 2019, 66, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S.-P.; Yoo, H.S.; Choi, S. Ten years of research change using Google Trends: From the perspective of big data utilizations and applications. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 130, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önder, I. Forecasting tourism demand with Google Trends: Accuracy comparison of countries versus cities. Int. J. Tourism Res. 2017, 19, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño Romarís, C.A. Patrimonio enograstronómico y desarrollo local en el ámbito del espacio litoral gallego. In Actas del XV Coloquio Ibérico de Geografía: Retos y tendencias de la Geografía Ibérica; García Marín, R., Alonso Sarria, F., Belmonte Serrato, F., Moreno Muñoz, D., Eds.; AGE-UMU: Murcia, Spain, 2016; pp. 711–721. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Cherres, J.; Zaldumbide-Peralvo, D. Estrategias digitales para la personalización de experiencias de viaje en la provincia Manabί. 593 Digit. Publ. CEIT 2024, 9, 696–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tool | Main Use | Successful Experiences |

|---|---|---|

| Social media/influencer marketing | Publish photos/videos of dishes, publicise gastronomic events, collaborations with influencers. | Official campaigns (e.g., # DameGalicia), destination profiles (Turismo de Galicia shows showcookings), gastronomic influencers (@senparaxe, @robegrill, @foodtropia, @cenandocongonzalo, …). |

| Content marketing | Websites and blogs with articles, interactive maps and gastronomic guides. | Official websites (e.g., “Paseando entre viñedos”), food bloggers (Available online: fedegustando.com (accessed on 20 July 2025)), local chefs (Recetas de Rechupete, La Cocina de Frabisa, La Cocina de Lechuza, …) |

| Specialised mobile platforms/Apps | Mobile guides with geolocation and restaurant and producer profiles. | My trip (Turismo de Galicia provides this platform to facilitate the management of the visit, with thematic itineraries gastronomic including (Available online: https://www.turismo.gal/a-mina-viaxe (accessed on 20 July 2025)) Enoturismo Galicia (215 resources and multilingual info), Turismo de Galicia app (restaurants, accommodation). |

| Augmented Reality/VR | Interactive experiences: virtual tours, virtual signage of nearby venues. | App RA de Turismo de Galicia (points out restaurants and tourist offices nearby), 360° tours of wineries or gastronomic museums. |

| Targeted digital advertising | Geolocated online ads, email marketing with special offers. | Google Ads and social media campaigns, newsletters with restaurant discounts. |

| Online analytics and reputation | Monitor social media mentions and online reviews to assess the reputation of Galicia as a gastronomic destination. | SIT (Tourist Intelligence System) of SEGITTUR (Available online: https://sistemainteligenciaturistica.es (accessed on 20 July 2025)). Tourist Observatory of Ribeira Sacra (Available online: https://turismo.ribeirasacra.org/pt/observatorio-turistico-de-ribeira-sacra (accessed on 20 July 2025)). |

| Posición en el Ranking | Nombre del Producto | Veces Repetido |

|---|---|---|

| 16 | Aceite | 53 |

| 17 | Caldo | 52 |

| 27 | Carne | 45 |

| 28 | Pemento | 44 |

| 47 | Pan | 34 |

| 49 | Polbo | 34 |

| 50 | Polo | 34 |

| 55 | Cocido | 29 |

| 63 | Percebe | 28 |

| 64 | Empanada | 28 |

| 69 | Sal | 27 |

| 77 | Allo | 26 |

| 79 | Lacón | 25 |

| 81 | Marisco | 25 |

| 83 | Mel | 25 |

| 90 | Berberecho | 24 |

| 91 | Mexillón | 24 |

| Total | 557 |

| Category | Product | Español Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Sea products | Pulpo | Octopus |

| Percebe | Gooseneck barnacle | |

| Mejillón | Mussel | |

| Berberecho | Cockle | |

| Marisco | Seafood | |

| Meat products | Caldo | Broth |

| Cocido | stew | |

| Empanada | Pie | |

| Lacón | pork shoulder | |

| Wines | Albariño | Albariño |

| Monterrei | Monterrei | |

| Ribeiro | Ribeiro | |

| Valdeorras | Valdeorras |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martins-Rodal, B.; Patiño Romarís, C.A. Gastronomic Tourism and Digital Place Marketing: Google Trends Evidence from Galicia (Spain). World 2025, 6, 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040135

Martins-Rodal B, Patiño Romarís CA. Gastronomic Tourism and Digital Place Marketing: Google Trends Evidence from Galicia (Spain). World. 2025; 6(4):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040135

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartins-Rodal, Breixo, and Carlos Alberto Patiño Romarís. 2025. "Gastronomic Tourism and Digital Place Marketing: Google Trends Evidence from Galicia (Spain)" World 6, no. 4: 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040135

APA StyleMartins-Rodal, B., & Patiño Romarís, C. A. (2025). Gastronomic Tourism and Digital Place Marketing: Google Trends Evidence from Galicia (Spain). World, 6(4), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040135