Revealing the Key Determinants of Green Purchase Intentions: Insights from an Extended UTAUT2 Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

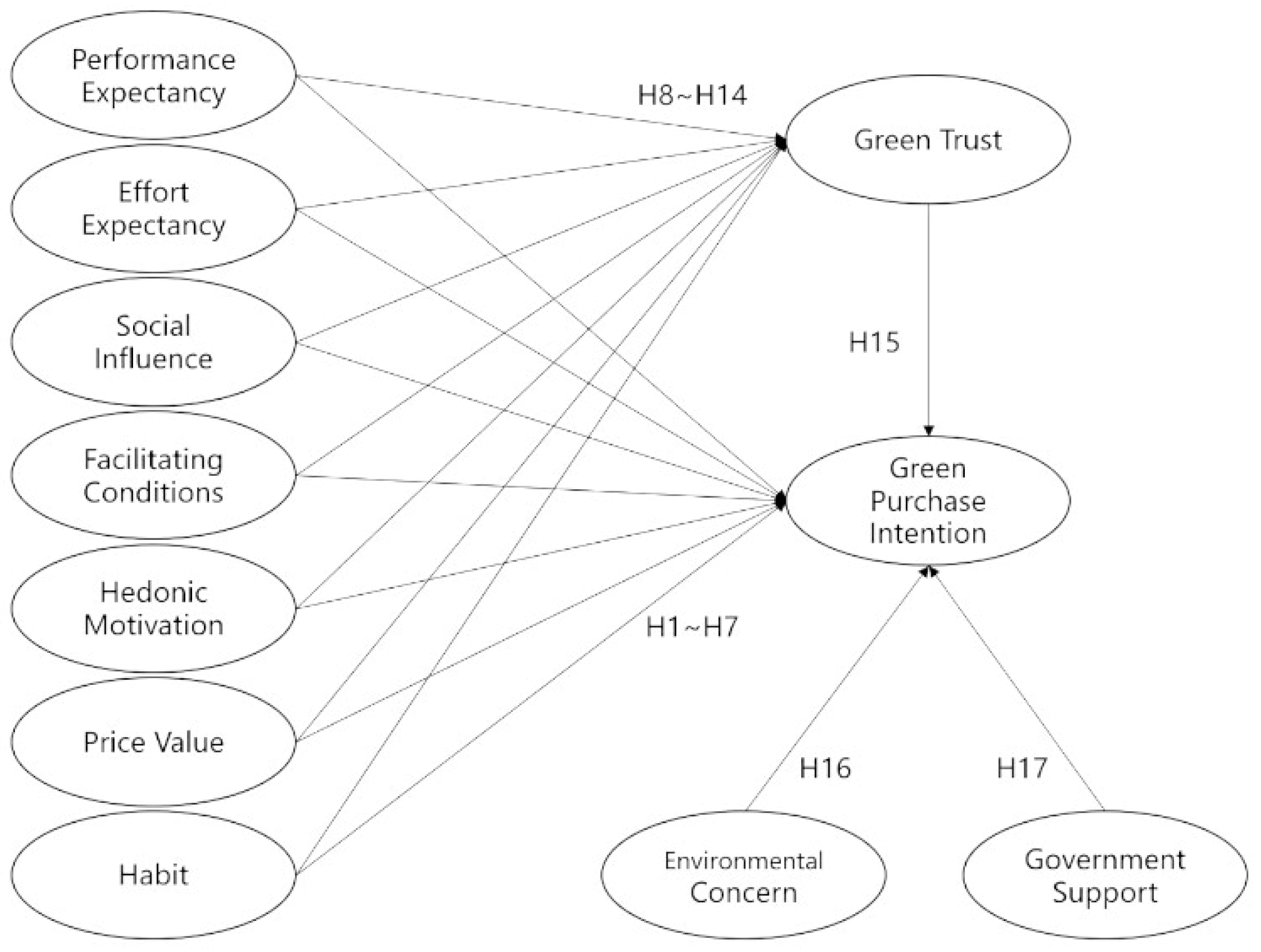

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. UTAUT2 and Extended Model

2.2. The Role of GT in the Model

2.3. EC and GS

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Analysis Methods

3.2. Measurement Instruments

4. Research Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model

5. Discussion

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, Y.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Z. The Impact Mechanism of Government Environmental Regulation and Green Consumer Orientation (GCO) on Green Purchase Intention: A Case Study of Zespri. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Li, Y. Exploring the Impact of the Green Marketing Mix on Environmental Attitudes and Purchase Intentions: Moderating Role of Environmental Knowledge in China’s Emerging Markets. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aflak, A.; Gawshinde, S. How Perceived Usefulness Leads to Green Purchase Intention with a Mediating Effect. Contad. Adm. 2024, 69, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, A.; Sharma, M. Artificial Intelligence and Consumer’s Perception: A Research on Environmentally Conscious Consumer. J. Metaverse 2024, 4, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, K.V.; Uehara, T. The Influence of Key Opinion Leaders on Consumers’ Purchasing Intention Regarding Green Fashion Products. Front. Commun. 2023, 8, 1296174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, K.C.; Nguyen-Viet, B.; Phuong Vo, H.N. Toward Sustainable Development and Consumption: The Role of the Green Promotion Mix in Driving Green Brand Equity and Green Purchase Intention. J. Promot. Manag. 2023, 29, 824–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhao, H.; Li, T. The Role of Live-Streaming e-Commerce on Consumers’ Purchasing Intention Regarding Green Agricultural Products. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, M.T.; Jacob, J. The Relationship between Green Perceived Quality and Green Purchase Intention: A Three-Path Mediation Approach Using Green Satisfaction and Green Trust. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2018, 15, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. Environmental Knowledge and Green Purchase Intention and Behavior in China: The Mediating Role of Moral Obligation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, W.; Zhu, R.; Liu, W.; Liu, Q. Understanding the Influences on Green Purchase Intention with Moderation by Sustainability Awareness. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Augusto, J.A.; Garrido-Lecca-Vera, C.; Lodeiros-Zubiria, M.L.; Mauricio-Andia, M. Green Marketing: Drivers in the Process of Buying Green Products—The Role of Green Satisfaction, Green Trust, Green WOM and Green Perceived Value. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamilmani, K.; Rana, N.P.; Wamba, S.F.; Dwivedi, R. The Extended Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT2): A Systematic Literature Review and Theory Evaluation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 57, 102269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbulú Ballesteros, M.A.; Acosta Enríquez, B.G.; Ramos Farroñán, E.V.; García Juárez, H.D.; Cruz Salinas, L.E.; Blas Sánchez, J.E.; Arbulú Castillo, J.C.; Licapa-Redolfo, G.S.; Farfán Chilicaus, G.C. The Sustainable Integration of AI in Higher Education: Analyzing ChatGPT Acceptance Factors Through an Extended UTAUT2 Framework in Peruvian Universities. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, G.; Luo, H.; Yin, W.; Zhang, Y. Exploration of the Application and Practice of Digital Twin Technology in Teaching Driven by Smart City Construction. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Hu, J.; Liu, D.; Zhou, C. Towards Sustainable Healthcare: Exploring Factors Influencing Use of Mobile Applications for Medical Escort Services. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilal, A.; Varela-Neira, C. Understanding Consumer Adoption of Mobile Banking: Extending the UTAUT2 Model with Proactive Personality. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M.; Zheng, G.; Hamayun, M.; Ibrahim, A.M. The Antecedents of Willingness to Adopt and Pay for the IoT in the Agricultural Industry: An Application of the UTAUT 2 Theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, L.; Li, K.; Jiang, M.; Jiang, X. Exploring the Factors Influencing Tourists’ Satisfaction and Continuance Intention of Digital Nightscape Tour: Integrating the Design Dimensions and the UTAUT2. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poureisa, A.; Aziz, Y.A.; Ng, S.-I. Swipe to Sustain: Exploring Consumer Behaviors in Organic Food Purchasing via Instagram Social Commerce. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.K.S.; German, J.D.; Redi, A.A.N.P.; Cordova, L.N.Z.; Longanilla, F.A.B.; Caprecho, N.L.; Javier, R.A.V. Antecedents of Behavioral Intentions for Purchasing Hybrid Cars Using Sustainability Theory of Planned Behavior Integrated with UTAUT2. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Luo, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Zou, J.; Masukujjaman, M.; Ibrahim, A.M. Modeling the Enablers of Consumers’ E-Shopping Behavior: A Multi-Analytic Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasingh, S.; Girija, T.; Arunkumar, S. Determinants of Omnichannel Shopping Intention for Sporting Goods. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimborazo-Azogue, L.-E.; Frasquet, M.; Molla-Descals, A.; Miquel-Romero, M.-J. Understanding Mobile Showrooming Based on a Technology Acceptance and Use Model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhu, N.T.; My, D.V.; Thu, N.T.K. Determinants Affecting Green Purchase Intention: A Case of Vietnamese Consumers. J. Manag. Inf. Decis. Sci. 2019, 22, 136–137. [Google Scholar]

- Truc, L.T. Greening the Future: How Social Networks and Media Shapes Youth’s Eco-Friendly Purchases. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyal, S.; Ahmed, M.J.; Ahmad, R.; Khan, B.S.; Xin, C. Factors Influencing Green Purchase Intention: Moderating Role of Green Brand Knowledge. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajar, R.G.C.A.; Ong, A.K.S.; German, J.D. Determining Sustainable Purchase Behavior for Green Products from Name-Brand Shops: A Gen Z Perspective in a Developing Country. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, B.; Hwang, H.-G. Consumers Purchase Intentions of Green Electric Vehicles: The Influence of Consumers Technological and Environmental Considerations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kumaim, N.H.; Shabbir, M.S.; Alfarisi, S.; Hassan, S.H.; Alhazmi, A.K.; Hishan, S.S.; Al-Shami, S.; Gazem, N.A.; Mohammed, F.; Abu Al-Rejal, H.M. Fostering a Clean and Sustainable Environment through Green Product Purchasing Behavior: Insights from Malaysian Consumers’ Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology: A Synthesis and the Road Ahead. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2016, 17, 328–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Musa, R.; Kou, S. Research on the Green Purchase Intentions and Driving Factors of Generation Z in Developing Countries. Malays. J. Consum. Fam. Econ. 2024, 33, 62–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Jafar, R.M.S.; Waheed, A.; Sun, H.; Kazmi, S.S.A.S. Determinants of CSR and Green Purchase Intention: Mediating Role of Customer Green Psychology During COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 389, 135888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzin, M.; Sadeghi, M.; Yahyayi Kharkeshi, F.; Ruholahpur, H.; Fattahi, M. Extending UTAUT2 in M-Banking Adoption and Actual Use Behavior: Does WOM Communication Matter? Asian J. Econ. Bank. 2021, 5, 136–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gansser, O.A.; Reich, C.S. A New Acceptance Model for Artificial Intelligence with Extensions to UTAUT2: An Empirical Study in Three Segments of Application. Technol. Soc. 2021, 65, 101535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, T.-H.; Chao, C.-M.; Liu, H.-H.; Chen, D.-F. Developing an Extended Theory of UTAUT 2 Model to Explore Factors Influencing Taiwanese Consumer Adoption of Intelligent Elevators. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440221142209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manogaran, P.; Teoh, A.P. Determinants of Smart City Technology Acceptance: Role of Smart Governance as Moderator. J. Gov. Integr. 2023, 6, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.-H.; Nguyen, D.N.; Nguyen, L.A.T. Quantitative Insights into Green Purchase Intentions: The Interplay of Health Consciousness, Altruism, and Sustainability. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2253616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Furuoka, F.; Rasiah, R.A.; Shen, E. Consumers’ Purchase Intention toward Electric Vehicles from the Perspective of Perceived Green Value: An Empirical Survey from China. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktaviani, R.D.; Naruetharadhol, P.; Padthar, S.; Ketkaew, C. Green Consumer Profiling and Online Shopping of Imperfect Foods: Extending UTAUT with Web-Based Label Quality for Misshapen Organic Produce. Foods 2024, 13, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, S.; Tarun, M.T. Effect of Consumption Values on Customers’ Green Purchase Intention: A Mediating Role of Green Trust. Soc. Responsib. J. 2021, 17, 1320–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.M.L.; Cheung, C.T.Y.; Lit, K.K.; Wan, C.; Choy, E.T.K. Green Consumption and Sustainable Development: The Effects of Perceived Values and Motivation Types on Green Purchase Intention. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 1024–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-C. News Consumption and Green Habits on the Use of Circular Packaging in Online Shopping in Taiwan: An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1025747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S. The Drivers of Green Brand Equity: Green Brand Image, Green Satisfaction, and Green Trust. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enaizan, O.; Eneizan, B.; Almaaitah, M.; Al-Radaideh, A.T.; Saleh, A.M. Effects of Privacy and Security on the Acceptance and Usage of EMR: The Mediating Role of Trust on the Basis of Multiple Perspectives. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2020, 21, 100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Rashidin, M.S.; Song, F.; Wang, Y.; Javed, S.; Wang, J. Determinants of Consumer’s Purchase Intention on Fresh E-Commerce Platform: Perspective of UTAUT Model. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211027875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnoor, A.; Al-Abrrow, H.; Al Halbusi, H.; Khaw, K.W.; Chew, X.; Al-Maatoq, M.; Alharbi, R.K. Uncovering the Antecedents of Trust in Social Commerce: An Application of the Non-Linear Artificial Neural Network Approach. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2022, 32, 492–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehpour, M.; Yin Chau, K.; Du, L.; Qiu, R.; Lin, C.-Y.; Batbayar, B. Predictors of Green Purchase Intention toward Eco-Innovation and Green Products: Evidence from Taiwan. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2023, 36, 2121934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, N.; Çoknaz, D. The Role of Environmental Concern in Mediating the Effect of Personal Environmental Norms on the Intention to Purchase Green Products: A Case Study on Outdoor Athletes. ReMark-Rev. Bras. Mark. 2022, 21, 1282–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazish, M.; Khan, M.N.; Khan, Z. Environmental Sustainability in the Digital Age: Unraveling the Effect of Social Media on Green Purchase Intention. Young Consum. 2024, 25, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnappan, P.; Salim, F.A.A.; Maideen, M.B.H.; Kunjiapu, S. The Effect of Environmental Concern and Global Environmental Connectedness on Green Purchase Intention of Hotel Customers in Malaysia. Int. J. Sustain. Soc. 2023, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouteraa, M. Mixed-Methods Approach to Investigating the Diffusion of FinTech Services: Enriching the Applicability of TOE and UTAUT Models. J. Islam. Mark. 2024, 15, 2036–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, P.-S.; Lim, X.-J.; Wong, L.-J.; Lee, K.Y.M. Thank You, Government! Your Support Facilitated My Intention to Use Mobile Payment in the New Normal Era. Span. J. Mark.-ESIC 2025, 29, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.-L.; Hsu, C.-H.; Chan, Y.-W. Constructing a B2C Repurchase Intention Model Based on Consumer Perceptive Factors. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2015, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, C.; Singhal, N.; Tiwari, S. Antecedents of Consumer Environmental Attitude and Intention to Purchase Green Products: Moderating Role of Perceived Product Necessity. Int. J. Environ. Technol. Manag. 2017, 20, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D.V.; Tung, L.T. Environmental Concern, Perceived Marketplace Influence and Green Purchase Behavior: The Moderation Role of Perceived Environmental Responsibility. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2024, 44, 1024–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Sheng, T.; Zhou, X.; Shen, C.; Fang, B. How Does Young Consumers’ Greenwashing Perception Impact Their Green Purchase Intention in the Fast Fashion Industry? An Analysis from the Perspective of Perceived Risk Theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, G.; Paul, J. CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM Methods for Research in Social Sciences and Technology Forecasting. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. An Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R; Classroom Companion: Business; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–29. ISBN 978-3-030-80518-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.P.; Marsh, H.W. Choosing a Multivariate Model: Noncentrality and Goodness of Fit. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Hong, S. Power Analysis in Covariance Structure Modeling Using GFI and AGFI. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1997, 32, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, T.A.; Schumacker, R.E. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Cengage: Noida, India, 2019; ISBN 978-1-4737-5654-0. [Google Scholar]

- Torkzadeh, G.; Koufteros, X.; Pflughoeft, K. Confirmatory Analysis of Computer Self-Efficacy. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2003, 10, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvi, M.S.; Önem, Ş. Impact of Variables in the UTAUT 2 Model on the Intention to Use a Fully Electric Car. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naaman, D.; Yeşilada, F.; Aghaei, I. A Moderated Mediation Analysis of Lebanon’s Food Consumers’ Green Purchasing Intentions: A Path Towards Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manutworakit, P.; Choocharukul, K. Factors Influencing Battery Electric Vehicle Adoption in Thailand—Expanding the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology’s Variables. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-M.; Kao, W.-Y.; Liu, W.-C. Navigating Sustainable Mobility in Taiwan: Exploring the Brand-Specific Effects of Perceived Green Attributes on the Green Purchase Intention for Battery Electric Vehicles. Sustainability 2025, 17, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, R.; Yang, Q.; Ahmed, M.A.O.; Hasan, G. E-Commerce for a Sustainable Future: Integrating Trust, Product Quality Perception, and Online-Shopping Satisfaction. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.H. A Study on the Application of Kiosk Service as the Workplace Flexibility: The Determinants of Expanded Technology Adoption and Trust of Quick Service Restaurant Customers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, C.; Wang, L. The Docking Mechanism of Public and Enterprise Green Behavior in China: A Scenario Game Experiment Based on Green Product Classification. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Classification | Frequency (n = 590) | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 245 | 41.5 |

| Female | 345 | 58.5 | |

| Age | Younger than 18 years old | 19 | 3.2 |

| 18–25 years old | 101 | 17.1 | |

| 26–35 years old | 110 | 18.6 | |

| 36–45 years old | 159 | 26.9 | |

| Older than 45 years old | 201 | 34.1 | |

| Education | Senior high school | 61 | 10.3 |

| University/college | 351 | 59.5 | |

| Graduate school | 178 | 30.2 | |

| Monthly Income | Less than TWD 30,000 | 155 | 26.3 |

| TWD 30,001–40,000 | 126 | 21.4 | |

| TWD 40,001–50,000 | 114 | 19.3 | |

| TWD 50,001–60,000 | 71 | 12.0 | |

| More than TWD 60,000 | 124 | 21.0 |

| Variables | Items | References |

|---|---|---|

| PE | PE1: Using green products will positively impact my daily life. PE2: Purchasing green products helps me achieve my environmental objectives. PE3: Purchasing green products enhances my quality of life. | [13] |

| EE | EE1: Purchasing green products is convenient. EE2: Purchasing green products is not a burden for me. EE3: The process of selecting and purchasing green products is straightforward. | [13] |

| SI | SI1: My family and friends recommend purchasing green products. SI2: My family and friends support my decision to purchase green products. SI3: My family and friends prefer to purchase green products. | [13] |

| FC | FC1: I can easily search for channels, such as retail stores or online platforms, to purchase green products. FC2: I have sufficient resources, including financial and informational assets, to purchase and use green products. FC3: Green products align with my consumption habits and do not cause any inconvenience during use. FC4: I have access to essential guidance and support when selecting or using green products. | [13] |

| HM | HM1: Selecting and purchasing green products provides a sense of satisfaction. HM2: Selecting and purchasing green products is enjoyable. HM3: Selecting and purchasing green products can be highly entertaining. | [13] |

| PV | PV1: Purchasing green products is beneficial for individuals. PV2: The prices of green products are reasonable because they significantly benefit the environment. PV3: The price of green products reflects their actual value. | [13] |

| HT | HT1: I am accustomed to purchasing green products. HT2: I often select green products as my preferred option. HT3: I will continue to purchase green products, even without promotions or incentives. | [13] |

| GT | GT1: Green products comply with applicable environmental standards and regulations. GT2: The manufacturers’ commitments and guarantees regarding green products are trustworthy. GT3: Green products can meet individual environmental performance expectations. GT4: Green products fulfill their commitments and responsibilities to environmental protection. | [26] |

| EC | EC1: I am deeply concerned about the deteriorating quality of the environment. EC2: Environmental protection is an issue that I frequently emphasize. EC3: I actively engage in matters concerning environmental conservation. EC4: I often consider methods to improve environmental quality. | [26] |

| GS | GS1: The government actively encourages and promotes the use of green products. GS2: The government provides incentive mechanisms, including subsidies and tax incentives, to encourage the development of green products. GS3: The government has implemented clear regulations and standards to encourage the widespread adoption and use of green products. | [19] |

| GPI | GPI1: Based on environmental considerations, I would purchase green products. GPI2: I would choose to support more environmentally friendly green products. GPI3: I am committed to increasing the frequency of my purchases of green products in the future. GPI4: In the future, I will continue to purchase green products. | [26] |

| Variable | Item | Standardized FL | S.E. | C.R. | p | SMC | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | PE1 | 0.79 | 0.62 | 0.84 | 0.64 | |||

| PE2 | 0.75 | 0.05 | 17.78 | *** | 0.56 | |||

| PE3 | 0.86 | 0.05 | 20.52 | *** | 0.74 | |||

| EE | EE1 | 0.70 | 0.49 | 0.84 | 0.63 | |||

| EE2 | 0.82 | 0.07 | 16.59 | *** | 0.67 | |||

| EE3 | 0.86 | 0.08 | 17.02 | *** | 0.74 | |||

| SI | SI1 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 0.95 | 0.85 | |||

| SI2 | 0.92 | 0.03 | 37.08 | *** | 0.84 | |||

| SI3 | 0.93 | 0.03 | 37.83 | *** | 0.86 | |||

| FC | FC1 | 0.77 | 0.60 | 0.88 | 0.65 | |||

| FC2 | 0.86 | 0.05 | 22.40 | *** | 0.74 | |||

| FC3 | 0.78 | 0.06 | 18.38 | *** | 0.61 | |||

| FC4 | 0.82 | 0.06 | 19.82 | *** | 0.67 | |||

| HM | HM1 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.95 | 0.86 | |||

| HM2 | 0.95 | 0.03 | 40.77 | *** | 0.90 | |||

| HM3 | 0.92 | 0.03 | 37.35 | *** | 0.85 | |||

| PV | PV1 | 0.70 | 0.49 | 0.85 | 0.65 | |||

| PV2 | 0.86 | 0.09 | 16.48 | *** | 0.73 | |||

| PV3 | 0.85 | 0.09 | 16.24 | *** | 0.72 | |||

| HT | HT1 | 0.77 | 0.60 | 0.84 | 0.64 | |||

| HT2 | 0.79 | 0.05 | 19.01 | *** | 0.62 | |||

| HT3 | 0.85 | 0.06 | 20.30 | *** | 0.73 | |||

| GT | GT1 | 0.82 | 0.68 | 0.90 | 0.70 | |||

| GT2 | 0.81 | 0.04 | 23.05 | *** | 0.66 | |||

| GT3 | 0.80 | 0.05 | 22.33 | *** | 0.64 | |||

| GT4 | 0.91 | 0.04 | 27.13 | *** | 0.82 | |||

| EC | EC1 | 0.73 | 0.54 | 0.86 | 0.61 | |||

| EC2 | 0.78 | 0.05 | 17.92 | *** | 0.60 | |||

| EC3 | 0.80 | 0.06 | 18.11 | *** | 0.64 | |||

| EC4 | 0.82 | 0.05 | 18.96 | *** | 0.67 | |||

| GS | GS1 | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.88 | 0.71 | |||

| GS2 | 0.81 | 0.04 | 22.37 | *** | 0.66 | |||

| GS3 | 0.87 | 0.04 | 24.13 | *** | 0.76 | |||

| GPI | GPI1 | 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.87 | 0.62 | |||

| GPI2 | 0.83 | 0.06 | 20.32 | *** | 0.69 | |||

| GPI3 | 0.78 | 0.06 | 18.53 | *** | 0.60 | |||

| GPI4 | 0.78 | 0.06 | 18.43 | *** | 0.61 | |||

| Fit Indices | CMIN/DF = 3.25 SRMR = 0.04 RMSEA = 0.06 | GFI = 0.85 AGFI = 0.82 NFI = 0.89 | TLI = 0.91 CFI = 0.92 IFI = 0.92 | |||||

| Hypothesized Path | Standardized Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | PE → GPI | 0.11 | 0.03 | 2.36 | * | Supported |

| H2 | EE → GPI | 0.21 | 0.04 | 3.76 | *** | Supported |

| H3 | SI → GPI | 0.12 | 0.03 | 2.13 | * | Supported |

| H4 | FC → GPI | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.946 | Not Supported |

| H5 | HM → GPI | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.812 | Not Supported |

| H6 | PV → GPI | 0.26 | 0.05 | 4.24 | *** | Supported |

| H7 | HT → GPI | 0.10 | 0.04 | 1.70 | 0.089 | Not Supported |

| H8 | PE → GT | 0.15 | 0.03 | 3.37 | *** | Supported |

| H9 | EE → GT | 0.33 | 0.04 | 6.94 | *** | Supported |

| H10 | SI → GT | 0.23 | 0.03 | 4.49 | *** | Supported |

| H11 | FC → GT | 0.32 | 0.03 | 7.01 | *** | Supported |

| H12 | HM → GT | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.80 | 0.422 | Not Supported |

| H13 | PV → GT | 0.32 | 0.04 | 6.31 | *** | Supported |

| H14 | HT → GT | 0.07 | 0.04 | 1.38 | 0.168 | Not Supported |

| H15 | GT → GPI | 0.23 | 0.06 | 3.45 | *** | Supported |

| H16 | GS → GPI | 0.12 | 0.02 | 2.70 | ** | Supported |

| H17 | EC → GPI | 0.11 | 0.06 | 2.03 | * | Supported |

| Path Relation | Indirect Effect | S.E. | Bias-Corrected Percentile Method (BC) | Percentile Method (PC) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | p | Lower | Upper | p | |||

| PE → GT → GPI | 0.034 | 0.017 | 0.009 | 0.088 | ** | 0.005 | 0.071 | * |

| EE → GT → GPI | 0.076 | 0.028 | 0.030 | 0.140 | ** | 0.020 | 0.133 | * |

| SI → GT → GPI | 0.053 | 0.025 | 0.014 | 0.117 | ** | 0.008 | 0.110 | * |

| FC → GT → GPI | 0.075 | 0.028 | 0.025 | 0.140 | ** | 0.017 | 0.129 | * |

| HM → GT → GPI | 0.005 | 0.008 | −0.006 | 0.026 | 0.313 | −0.009 | 0.021 | 0.474 |

| PV → GT → GPI | 0.072 | 0.032 | 0.022 | 0.158 | ** | 0.021 | 0.156 | * |

| HT → GT → GPI | 0.017 | 0.018 | −0.009 | 0.066 | 0.161 | −0.020 | 0.052 | 0.370 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chan, Y.-W.; Hsu, C.-H.; Hsu, S.-S. Revealing the Key Determinants of Green Purchase Intentions: Insights from an Extended UTAUT2 Model. World 2025, 6, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030089

Chan Y-W, Hsu C-H, Hsu S-S. Revealing the Key Determinants of Green Purchase Intentions: Insights from an Extended UTAUT2 Model. World. 2025; 6(3):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030089

Chicago/Turabian StyleChan, Ya-Wen, Che-Han Hsu, and Shiuh-Sheng Hsu. 2025. "Revealing the Key Determinants of Green Purchase Intentions: Insights from an Extended UTAUT2 Model" World 6, no. 3: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030089

APA StyleChan, Y.-W., Hsu, C.-H., & Hsu, S.-S. (2025). Revealing the Key Determinants of Green Purchase Intentions: Insights from an Extended UTAUT2 Model. World, 6(3), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030089