Abstract

The integration of ethnoreligious minorities into labor markets, particularly among women, is a key contemporary issue. The present study examines the associations among labor market outcomes (employment status, job type—full-time/part-time, wages, and rank), level of religiosity and residential area (in or outside ethnic enclaves) among Arab Muslim and Christian women in Israel. Both groups reside in predominantly Jewish and Arab localities but differ in terms of religiosity, with Muslims being substantially more religious. Utilizing official data from the Social Survey of the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, covering a decade between 2013 and 2022, with a sample of 4112 participants, the study finds that both residential area and religiosity are associated with labor market outcomes, particularly among Muslim women. Religiosity is negatively associated with employment quality measures (job type, wages, and rank), while residing in predominantly Jewish localities is positively associated with labor market participation. An interaction effect is observed regarding wages and type of position (full/part time). This study contributes to theory by introducing residential area as a new factor explaining the negative association between religiosity and labor market outcomes, as well as advancing agent-based approaches to study ethnic enclaves.

1. Introduction

The integration of ethno-religious minorities into labor markets in multi-ethnic societies is a pressing contemporary issue, with particular focus on women due to their oftenlimited representation [1,2,3,4]. In this context, the present study explores the relationships between employment indicators (labor market participation, job type—full- or part-time, wages, and rank); religiosity; and residential location (inside or outside ethnic enclaves) among Arab Muslim and Christian women in Israel.

Religiosity has garnered substantial scholarly attention regarding women’s integration into contemporary labor markets, revealing a negative relationship with labor market outcomes [5,6,7,8]. The current study advances this field by incorporating residential area into the analysis of the associations between religiosity and labor market outcomes.

Residential area is a core variable in the dual economy theory comparing minority members living in or outside ethnic enclaves. The latter refer to neighborhoods or areas within metropolitan fabrics where most residents belong to a minority group [9,10,11,12]. The evidence on the role of ethnic enclaves in the labor market outcomes of minority individuals, particularly women, is mixed. It is often argued that these enclaves encourage women’s employment due to physical and cultural proximity, where social networks help facilitate job opportunities [13,14]. However, contrary findings suggest that women’s integration in these settings remains limited to low-wage, low-skill occupations with scarce promotion opportunities [15,16].

We choose to focus this study on women as apparently religiosity and residential areas substantially affect their employment patterns. Both variables can affect their labor market outcomes for reasons attributed to their societies, such as the patriarchy as well as the labor market namely discrimination by employers and peers, particularly of women with a clearly identifiable religious appearance.

To the best of our knowledge, the combined effects of religiosity and residential location (within or outside ethnic enclaves) on the labor market outcomes of women from minority groups have not been studied. Examining these factors jointly is important, as it is expected to provide a more comprehensive understanding of women’s integration into modern economies. This is particularly important due to the close connection between these domains in labor market contexts. Living in an ethnic enclave may be associated with stronger religious values, and high religiosity can potentially create barriers to participating in the paid labor market [3,17]. Moreover, religious values may limit access to higher-quality positions that require significant interaction with the majority population [5,18].

The case of Arab Muslim and Christian women offers a compelling framework for this inquiry. Substantial evidence indicates that both religiosity [19,20,21] and residential area [22,23] are closely linked to Arab women’s labor market outcomes. Both Muslim and Christian women are likely to exhibit distinct relationships among religiosity, residential areas and employment patterns, thereby providing a richer perspective on the phenomenon under study. While these groups often share residential spaces in both Arab- and Jewish-majority localities, they differ significantly in levels of religiosity—Muslim women tend to demonstrate markedly higher religious observance [24,25]. The main group studied here are Muslim women characterized by high religiosity and residential segregation; these women have been extensively studied in Israel and other contexts [7,19,20,26]. Christian women provide a comparable group characterized by lower religiosity and lower segregation.

This study contributes to the literature on integration of ethnic minorities into contemporary labor markets. Namely, the labor market integration of minority women as a function of religion, residential area, and their interaction. Specifically, the study contributes to debates on religiosity and labor market outcomes of minority women by addressing an additional explanation—residential areas for the association between religiosity and labor market outcomes of women affiliated with minority groups. It seeks to illuminate whether the negative effect of religiosity on employment patterns is affected also by the type of residential area.

The study contributes also to dual economy debates. While most studies in this area focus on ethnic identity as a binary factor (belonging to an ethnic group or not), recent research has begun addressing the diversity within minority groups living in ethnic enclaves [27,28]. The current study aligns with this trend by unpacking the complexities of minorities living in ethnic enclaves, considering not just ethnicity, but also culture, language, and religion. Specifically, it adds value by examining the significance that residents attribute to their religiosity.

1.1. Religiosity and Labor Market Integration of Women Affiliated with Ethno-Religious Minorities

The relationship between religiosity and labor market integration has attracted significant attention [5,6,7,8,21]. This body of literature has primarily focused on Western countries, where women from minority groups are immigrants, particularly Muslims. Overall, these studies reveal a negative association between religiosity and labor market outcomes across various occupational measures, such as employment rates, wages, and working hours [17,18,29]. While similar patterns are observed among women affiliated with other religions [3,8], Muslim women seem to face greater penalties, reflected in lower employment rates and reduced job quality [5,7,30,31].

Various explanations have been proposed for the negative relationship between religiosity and labor market integration. Some suggest that religious commandments prioritize women’s family caregiving roles over their economic and personal fulfilment [32]. Although Abdelhadi and England [1] did not find support for this claim, other studies have highlighted factors such as lower educational attainment and immigration-related issues—such as citizenship status, language proficiency, relevant work experience, recognition of foreign qualifications, and limited social networks—as potential explanations [3,18,31,33]. Additional explanations consider demographic and personal characteristics of women with traditional values, especially those who place significant emphasis on their religious identity. According to this perspective, women who value religious principles may prioritize family, marry and become mothers at a younger age, have more children, and consequently experience lower labor market outcomes [5,7,18,33].

Labor market factors have also been proposed as explanations for the negative association between religiosity and labor market integration. For instance, a variety of discriminatory practices suggest that women from minority groups, especially Muslims, face a double penalty due to both their ethnic affiliation and their religiosity [6,26]. Such discriminatory practices are particularly pronounced for women with visible Islamic or traditional appearances, like those wearing the hijab or traditional dress [1,34,35]. Some have attributed these challenges to Islamophobia and fear of immigrants, which often target women with distinct religious appearances [34,35]. Others have argued that commercial-neoliberal perspectives view Muslim women as potentially alienating to customers [36]. Additionally, government policies and employer practices play a role in promoting or hindering the integration of women from minority groups [37].

Based on these explanations we can infer that the religiosity of women affiliated with ethnic minority groups is likely negatively associated with their labor market outcomes, including employability, job type (full-time/part-time), wages, and rank. Residential areas—whether inside or outside ethnic enclaves—has received limited scholarly attention in the literature on religiosity and labor market integration. Due the associations between religiosity tendencies and living in ethnic enclaves, it seems interesting to investigate these domains together.

1.2. The Dual Economy, Ethnic Enclaves and Labor Market Integration of Women

A substantial number of minority communities in Western countries live in ethnic enclaves. The latter are urban areas or neighborhoods where ethnic minorities form the majority. They often emerge due to large-scale migration, particularly to developed countries, and are typically found in large cities with high labor demand. They are characterized by lower real estate prices and the ability to offer services tailored to the specific population, hence serving as destinations for chain migration [9,10,14,38]. Over time, minority residents who have improved their socioeconomic status often move to suburbs or other neighborhoods with higher living standards. Thus, members of ethnic enclaves may experience lower levels of social integration and are more likely to adhere to traditional and religious lifestyles. Given their cultural makeup and spatial distribution, these areas tend to be socially and economically segregated [39,40].

These communities typically form an economy substantially different from the majority dominated state economy, hence referred to as the dual economy. The state economy leans toward global horizons including large scale supply chains and uses advanced technologies, while the ethnic economy is characterized by being locally based, limited in supplies and is predominated by simple, low-tech services [10,11,38,39,40,41].

Within the context of labor market integration, ethnic enclaves and other spatial aspects like commuting time and neighborhood job contacts were studied and analyzed across various ethno-religious minorities. This literature has addressed issues such as the size of ethnic enclave and its relation to different ethnic groups [9,16,42], behavior of buyers and sellers in ethnic enclaves based on ethno-religious affiliations, as well as business ownership [15,16,43].

Previous studies have presented contradictory evidence regarding whether residence in ethnic enclaves encourages or discourages minority employment. Some argue that living in ethnic enclaves limits minorities’ participation in employment due to restricted opportunities, particularly for quality occupations. These positions are often scarce in areas primarily serving the local ethnic economy, compared to areas dominated by the majority. Additionally, ethnic enclaves typically receive limited investment from both the government and private sectors, resulting in fewer and lower-quality job opportunities [13,14,44]. Conversely, others claim that living in ethnic enclaves promotes minority occupational participation, especially for women, given the proximity of residential and workplace areas and cultural factors. In these enclaves, minority members benefit from using their own language and practicing their cultural values and traditions [14,45,46].

Specifically, Muslim women with an emphasized religious identity might find it easier to integrate into the labor market within their ethnic enclave. The cultural environment of the enclave helps them adapt and integrate into local employment, and they likely encounter less discrimination within the enclave compared to outside areas [19,20,47]. Most business owners within the enclave are from the same ethnic group and are more likely to be accepting and sensitive to their religious background. Additionally, being in a patriarchal ingroup social environment can limit Muslim women’s employment opportunities outside their enclaves, as such employment might be viewed as a challenge to traditional values.

Living in ethnic enclaves might provide a good explanation for certain employment patterns among ethnic minorities but it bears a clear disadvantage by presenting all residents of a particular ethnic group in these areas as identical, without a reference to their intra-group and individual diversity. Some studies (mostly from recent years) have focused on the diversity in employment patterns within ethnic enclaves.

For instance, Light et al. [44] addressed this diversity by looking at subgroups of Iranians in the LA metropolitan area affiliated with four religions—Christian (Armenian), Bahais, Jewish and Muslim. They found substantial differences among these groups in terms of employment patterns (self-employed vs. employees) in addition to detachment among these enclaves, even though all these groups were affiliated with the same ethnonational origin. Likewise, Mok and Platt [28] focused on labor market outcomes of five Chinese groups living in ethnic enclaves in the London area—Chinese individuals born in the UK or outside the UK in mainland China, Taiwan, Hong-Kong or Malaysia. Taiwanese- and Malaysian-born Chinese individuals boasted the highest employment rates and wages, whereas their mainland China and Hong-Kong counterparts had inferior employment patterns. Similarly, Kesici [27] focused on integration of Turkish individuals from three ethnicities—Turkish, Kurdish and Cypriots living and working in the same ethnic enclave in northern London. This qualitative work reported important differences among these subgroups, with Turkish Kurds characterized by lower employment outcomes.

While these studies have been motivated by a desire to address diversity within groups in ethnic enclaves, they have not addressed diversity within ethnic subgroups by relating to personal factors of respondents such as their degree of religious identity. Additionally, ethno-religious identity is treated as dichotomous (being part of an ethno-religious group or not). The present study is part of this recent trend that corresponds to investigating diversity within minorities living in ethnic enclaves by looking at the salience respondents attribute to their religious identity (i.e., religiosity), measured quantitatively.

1.3. Context: Arabs in Israel

There are nearly two million Arabs in Israel, constituting about 20% of the total population. As an ethnonational minority with nominal citizenship, they face significant discrimination despite their formal citizenship status. Israel is often described as an ethnic democracy, a term that highlights the complex dynamics of ethnic and national identity within the state [48,49]. This is evident in daily practices as well as in certain discriminatory laws, such as the Law of Return (1950) that privileges Jewish immigration, and the Nation State Law (2018) formally designating Israel as the nation state of the Jewish people.

Arabs in Israel are subject to social marginality due to their distinct cultural and national Palestinian origin and because of the intractable Israeli-Palestinian conflict [24,48,49,50,51]. They are affiliated with three religious denominations: Muslims, Christians, and Druze; this study focuses on Muslims and Christians. Approximately 80% of the Arab population in Israel are Muslims. This community is experiencing a transition from a traditional to a modern lifestyle, leading to diverse expressions of Islam within the society. Some individuals adopt a highly conscious Islamic lifestyle, others practice Islam in more traditional ways, and a minority pursue a secular lifestyle [25,52,53].

Christian Arabs number approximately 140,000 (7% of Arab society) and generally have a relatively high socioeconomic status. For instance, in 2022, their fertility rate was 1.77, compared to 3.01 among Muslim women. Additionally, 83% of Christian Arab women held a matriculation diploma, compared to 69.5% of Muslim women, and 52% of them pursued academic studies eight years after high school graduation, compared to 34.1% of Muslim women. Furthermore, Arab Christians tend to adopt more modern and less patriarchal values, making them less religious [24,54].

The Druze have a unique relationship with the state, as they generally support it in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. They are excluded from this study because most Druze reside in only Arab localities, making it challenging to examine the role of ethnic enclaves in their situation.

About 90% of Muslims in Israel reside in Arab localities, while about 7% live in mixed Jewish-Arab localities (where the majority are Jews). The remainder have moved to predominantly Jewish neighborhoods and municipalities. In contrast, Arab Christians are more urbanized, with nearly 30% living in predominantly Jewish cities. Existing for many centuries, Arab localities in Israel have not formed as ethnic enclaves as in Western countries, yet they share similar characteristics. These locales are socioeconomically segregated, underdeveloped by the government, and due to the relatively small size of the country, they are part of Israel’s main metropolitan fabrics [55,56,57].

Since the early days of statehood, Arabs in Israel have been marginalized in the labor market, typically employed in lower-ranking occupations such as construction, agriculture, and manufacturing. This limited inclusion is largely due to discriminatory practices by both the government and employers, as well as lower education levels and limited employment opportunities within Arab localities [58,59,60]. Although educational attainment among Arabs has significantly improved over time, their employment still predominantly involves low blue-collar or basic service jobs, which are often less desirable to Jews, such as drivers, construction workers, and food industry employees. Nonetheless, a minority has managed to secure prestigious positions, particularly in the medical and education sectors, as well as in high-tech industries and academia [51,58,60,61,62].

Arab women exhibit significantly different employment patterns compared to their male counterparts. Only about 35% are employed, compared to approximately 70% of Jewish women and around 75% of Muslim-Arab men (who themselves are slightly less employed than Jewish men; ICBS 2023) [63]. The lower employment rate among Arab women is also reflected in the lower quality of their positions, including lower wages. Their average monthly wage is about NIS 6700, compared to NIS 9600 among Jewish women and NIS 9100 among Arab men (2017 data, pre-COVID-19). Additionally, Arab women’s representation in managerial positions is low, with only 2% holding such positions compared to 5.7% among Jewish women and 4.9% among Arab men [22,24].

Arab Christian women display markedly different employment patterns. Their employment rate is 55%, compared to 23% among Muslim women (and 34% among Druze women). This difference is also evident in the quality of occupations, with the average wage for Christian women being approximately 8300 NIS, compared to 6000 NIS for Muslim women [24].

Several barriers explain Arab women’s limited labor market integration. Marketwise, they include location of residency, as most Arab localities are in Israel’s socio-geographical periphery where quality employment opportunities are fewer, supplemented by discriminatory practices by employers in acceptance to jobs and in promotion. Discriminatory governmental policies such as limited development of labor opportunities within the Arab localities are also counted among the significant factors [20,22,55,64]. Commuting is another significant barrier as the public transportation network is not well developed in Arab localities, and since most Muslim women have opportunities only in low salary positions, they cannot afford purchasing and maintaining a private vehicle [23,65]. Women’s affiliation with a lower socioeconomic class puts them at risk for a lower educational level, inability to afford the cost of a daycare solution for their infants or the cost of extracurricular forums for their school-age children, as well as limited proficiency in Hebrew, and hence underdeveloped social networks with Jews [20,47,64,65].

In addition to higher educational levels, residential areas and traditional religious values provide significant explanations for the labor market inequalities between Muslim and Christian women. About 30% of Arab Christian women live in predominantly Jewish areas, which offer significantly more employment opportunities compared to approximately 7% of Muslim women. Arab Christian society tends to embrace modern values, which are considerably different from those in Muslim communities. The inclination towards traditional values among Arab Muslim women has been recognized as a barrier to their labor market integration. For instance, Abu-Rabia-Queder [19] and Shdema et al. [21] have identified religiosity as a barrier to employment, particularly when interacting with employers outside Arab localities. Yonay et al. [54] found that Muslim Arab women living in predominantly Muslim areas had lower employment rates compared to their counterparts in mixed Muslim-Christian localities. They suggested that this disparity was due to increased social interaction with Christian women, who generally had higher employment rates.

Arab localities face significant discrimination in terms of physical infrastructure and economic development compared to Jewish municipalities. These disparities contribute to substantial barriers for Arab women’s integration into the labor market, particularly due to the realities of ethnic enclaves (e.g., distance from employment hubs and patriarchal norms). Therefore, we hypothesize that Arab women residing in predominantly Jewish localities would experience advantages in employment compared to those living in predominantly Arab localities.

1.4. Research Objectives

The main objective of the current study is to examine the role of religiosity and area of residence in labor market integration of Arab Muslim and Christian women in Israel. The study sample is relevant for addressing this objective given the distinction between areas of residence (stable ethnic enclaves vs. mixed or predominantly Jewish areas) and given the diversity of Arab women (Muslim and Christian) in Israel in terms of religiosity. Accordingly, we hypothesized as follows:

H1. Religiosity would be negatively associated with employment outcomes (occupation status, type of occupation-full/pat time job; wages and rank) among both Muslim and Christian women.

H2. Living in predominantly Jewish areas would be associated with higher employment outcomes for Muslim and Christian women.

H3. Residential area would add to the associations between religiosity and labor market outcomes of Muslim and Christian women (religiosity × residence interaction).

In terms of religion and religiosity, Arabs in Israel represent a diverse minority group [21,52]; however, they are homogenous in terms of citizenship and ethnicity. By focusing on Christian- and Muslim-Arab women, we hold their citizenship, and ethnicity constant, thereby sharpening the comparisons between the effects of religiosity and area of residence on labor market outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The study utilizes data from the annual Social Survey conducted by the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (ICBS), which covers a wide range of topics. The survey is administered to a representative sample of 7500 adults drawn from the Ministry of the Interior’s Population Registry. For our analysis, we extracted and merged data from the survey collected over the decade from 2013 to 2022 (the most recent data available) to obtain a comprehensive view over time. We focused on Muslim and Christian Arab women who reported their religion and employment status. We excluded individuals who met the following criteria: (1) aged over 64 years (the retirement age for women according to International Labor Organization standards); (2) residents of East Jerusalem (as they are not Israeli citizens and face different employment opportunities compared to ordinary citizens); and (3) women for whom the area of residence (Arab, mixed/predominantly Jewish) could not be clearly determined from the survey data were excluded from the sample (the survey data present locality characteristics rather than the locality’s specific name). The result was a sample of 4112 respondents, of whom 88.8% were Muslim and the rest Christian.

To ensure the sample’s statistical power, we used G*Power (Version 3.1.9.4) [66] to determine the sample size required for a moderation analysis. Specifically, we estimated a linear multiple regression: fixed model, R2 increase. We used the following parameters: small effect size, f2 = 0.02; α = 0.05; power = 80%; nine tested predictors; and ten total predictors. This gave a minimum sample of 791 participants, while the sample used consists of 4112 participants.

Among the Muslim women, most (70.9%) were married, about 20.9% were single, and the remainder were separated (1.4%), divorced (4.1%), or widowed (2.7%). Most (73%) were mothers, with the number of their children ranging from one to seven (median = 3). Among Christian respondents, 66.6% were married, 28% were single, and 4.4% were divorced or widowed. Additionally, 68.1% were mothers, with the number of their children ranging from one to seven (median = 2).

Regarding educational attainment, 22.1% of Muslim respondents completed high school without a matriculation certificate (an educational certificate given by the state after completing high school studies and passing state exams); 29.1% completed high school with a matriculation certificate; 24.6% held a post-secondary non-academic diploma; 21.2% had a BA degree; and 3.9% attained an MA or higher degree. Among Christian respondents, 8.7% completed high school without a matriculation certificate; 21.4% had high school education with a matriculation certificate; 29.6% completed a post-secondary non-academic certificate; 32.9% held a BA or equivalent academic diploma; and 8.3% had an MA or higher degree.

2.2. Measures

Labor market outcomes. The first labor market variable examined was economic activity, which relates to employment status. Respondents in the ICBS survey were asked, “Did you work in the previous week?”, and, for those not working, “Are you actively looking for work?” Based on their responses, participants were categorized into three groups: (1) employed, (2) unemployed (not working but actively seeking employment), and (3) not participating in the labor market. Substantial differences were observed between Arab Muslim and Christian women regarding this measure.

Among Muslim women, 43.2% were employed, compared to 67.4% of Christian women. Unemployment rates were similar across both groups, at 7.6% for Muslims and 7.8% for Christians. However, a significantly higher proportion of Muslim women were not participating in the labor market, with 49.2% compared to 24.7% among Christian women.

For those employed, we further examined whether they held full- or part-time positions, their wages (classified into eight categories by the ICBS), and their rank (ordinary worker vs. manager). Arab Christian women showed significantly higher attainments in terms of full-time positions and wages, with no notable differences in rank between the two groups.

Area of residence. Most Muslim respondents (96.1%) resided in Arab localities and 3.9% resided in mixed or predominantly Jewish localities. Christian respondents were also living mostly in Arab localities (81.4%) but a significantly higher portions of them were living in predominantly Jewish localities (18.6%). We calculated respondents in mixed and predominantly Jewish localities together (hereafter, predominantly Jewish localities), because both types of localities are not part of the Arab ethnic enclaves and are marked by greater employment opportunities and social exposure to the Jewish majority.

Religiosity. Respondents’ religiosity was self-reported in the ICBS survey on a Likert scale, from 1 “non-religious” to 4 “very religious”. As expected, there were substantial differences in religiosity between Muslim and Christian women. Among Muslim women, 9.1% identified as non-religious compared to 34.9% of Christian women. Additionally, 19.4% of Muslim women reported being religious to some extent, whereas 32.3% of Christian women did. Most Muslim respondents (64.5%) considered themselves religious, while only 29% of Christian respondents did. Furthermore, 6.9% of Muslim women regarded themselves as very religious, compared to 3.7% of Christian women.

We also used the survey data on social integration, as there is substantial evidence linking such measures to the labor market outcomes of women from minority groups. Specifically, we focused on two key variables: Hebrew proficiency, which was calculated as the mean score on a scale from one to five assessing reading, writing, and speaking abilities, and perceived discrimination, calculated as the mean score on a binary scale reflecting experiences of discrimination based on national, ethnic, and religious grounds. Table 1 presents the demographic and labor market differences between Muslim and Christian women, highlighting the empirical basis for selecting these populations for the present study, particularly with relation to religiosity, residential areas, and labor market measures.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics. N for demographics and social integration characteristics: Muslim women = 3619; Christian women = 493; N for occupational measures (only for working women): Muslim = 1563; Christian = 332.

2.3. Data Analysis

We began our analysis by examining the bivariate associations between religiosity, residential area, and employment measures for both Muslim and Christian women. This was done using a series of chi-square tests. Next, we investigated the joint associations among employment status (working, unemployed, or out of the labor market), residential areas and religiosity, by performing multinomial logistic regressions for each sample (Muslim and Christian). Demographic variables were controlled in these analyses. The final stage of the analysis focuses on examining the relationship among residential areas, religiosity, and quality of employment measures, including full- versus part-time positions, wages, and rank. We employed binary logistic regression to analyze the relationship between residential areas, religiosity and full- versus part-time positions as well as rank (simple workers versus managers). For examining the relationship with wages, we applied OLS estimation (linear regressions). For all the regressions conducted, we also examined the moderation effect of residential area on the relationship between religiosity and labor market outcomes by including an interaction term.

3. Results

3.1. Bivariate Associations

Bivariate associations among employment measures, religiosity and residential areas for Muslim women (Table 2) reveal that residing in predominantly Jewish areas was significantly associated with employment status, but it was not associated with the quality measures of employment. Findings regarding religiosity reflect a clear pattern in the expected direction, with all employment measures examined: participation, full- vs. part-time employment, wages, and rank. In contrast, the analysis of Christian women revealed a different pattern. Living in predominantly Jewish localities was significantly associated with employment status, but it was not associated with any of the employment quality measures. Religiosity did not show any significant association with the employment measures studied.

Table 2.

Bivariate associations among religiosity, residential areas and employment measures for Muslim and Christian women. N Muslim women = 3619; N Christian women = 493.

3.2. Religiosity, Residential Areas and Employment Status

To determine whether religiosity (low vs. high) and area of residence (Arab vs. predominantly Jewish) were associated with employment status while controlling for demographics and social integration measures, we conducted a multinomial logistic regression with three categories: employed, unemployed, and not participating in the labor market. In this model, employed women served as the reference group, as we were particularly interested in comparing other groups to this group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multinomial Regression of employment status on religiosity, residential area and their interaction (Odds Ratio, OR are presented in the table) N Muslim women = 3619; N Christian women = 493.

Among Muslim women, both area of residence and religiosity were associated with employment status (in addition to positive association mainly with increased level of education). Specifically, Muslim women residing in Jewish areas had a reduced odds ratio (OR = 0.22) of not participating in the labor market (compared to being employed). However, their residential area was not associated with their odds of unemployment compared to being employed. Additionally, highly religious Muslim women had a higher odds ratio of 1.36 of not participating in the labor market (compared to being employed) than their low-religious counterparts. Similarly, highly religious Muslim women had a 1.4 odds ratio of being unemployed (compared to being employed) compared to less religious women. The interaction between area of residence and religiosity was not significant for the status of not participating in the labor market or being unemployed, compared to being employed. In addition, age and educational level were found to explain the likelihood of Muslim women to participate in the paid labor market.

Similarly to Muslim women, Christian women residing in Jewish areas had lower odds (OR = 0.09) of not participating in the labor market compared to being employed (in addition to a positive association with level of education and proficiency in Hebrew). However, their residential area was not associated with their odds of unemployment compared to being employed. Interestingly, among Christian women, religiosity played no role in employment status. Also here, the interaction between religiosity and area of residence was not significant for the status of not participating in the labor market or being unemployed, compared to being employed. Similarly to Muslim women, their Christian counterparts’ educational level was associated with the likelihood of being employed, but differently from Muslim women, their economic status played a role within Christians’ employment probability.

3.3. Religiosity, Residential Areas and Quality of Occupations

To examine the associations between residential area, religiosity, employment type (part- vs. full-time), and rank (worker vs. manager), we conducted binary logistic regressions. In addition, we used linear regression analyses to explore the relationship with wages (see Table 4). These analyses were restricted to employed participants, and demographic variables as well as social interaction measures were controlled for. As shown in Table 4, highly religious Muslim women had decreased odds (OR = 0.48) for being employed full-time and for occupying a managerial position (OR = 0.34; highly educated women and those affiliated with the main working ages were associated with having a full-time position). Religiosity was negatively associated with wages (β = −0.13) and with high level of education. Additionally, interaction effect between religiosity and residential area was evident in the association with position type (full-/part-time) (OR = 0.22) and wages (β = −0.10), but not with rank. Beyond the variables in the focus of this study, age and level of education were found to be associated with labor market outcomes among both Muslim and Christian women, but no substantial associations were found regarding position type or rank.

Table 4.

Logistic regressions of position type and rank on religiosity, residential area and their interaction (ORs are presented in the table) and linear regression of wages on religiosity, residential area and their interaction (β values). N Muslim women = 1563; N Christian women = 332.

Among Christian women, residential area, religiosity, and their interaction showed no association with the examined employment quality measures, nor an interaction effect. However, older age and higher education level were positively associated mainly with wages.

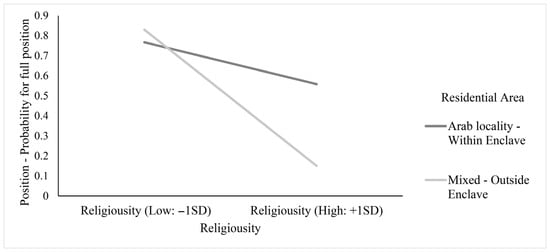

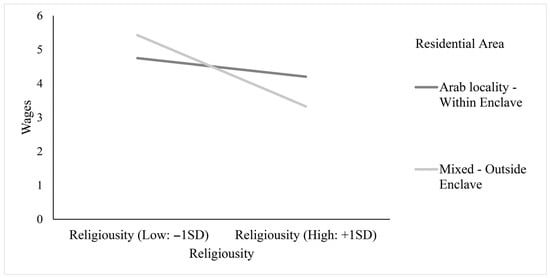

To analyze the significant interaction term, a simple slope analysis was conducted. Specifically, it was found that for those who work within their ethnic enclave there was a negative effect of religiosity on type of position (b = −0.67, se = 0.16, p < 0.001, OR = 0.51). Yet, a stronger negative effect was found for those who work outside their ethnic enclave (b = −2.10, se = 0.76, p = 0.01, OR = 0.12) (Figure 1). Specifically, these results indicate that the greater a person’s religiously, the less likely it is they will work in a full-time position and that this relationship is stronger outside the ethnic enclave than it is inside it. Regarding wages, a parallel exanimation uncovered that for those who work within their ethnic enclave, there was a negative relation between religiosity and wages (b = −0.37, se = 0.13, p = 0.004). Yet, a stronger negative effect was found for those who work outside their ethnic enclave (b = −1.25, se = 0.41, p = 0.003). The simple slopes are presented in Figure 2. Specifically, these results indicate that the greater a woman’s religiously is, the lower the salary she receives and that this relationship is stronger outside the ethnic enclave than it is inside.

Figure 1.

Simple Slopes for Religiosity on type of position (full/part time) at Different residential environments (Jewish/Arab).

Figure 2.

Simple Slopes for Religiosity on wages at Different residential environments (Jewish/Arab).

With respect to the research hypotheses, H1 addressing religiosity was supported for Muslim women but not for their Christian counterpart. H2 regarding residential area was supported for both populations regarding the odds to be employed but not regarding most quality measures of employment. H3 about the interaction effect of religiosity and residential area was partly supported for Muslim women as explaining quality measures of employment, namely type of position—full/part time—and wages, while it was rejected for rank and the likelihood of being employed. It was also rejected for Christian women in all occupational variables (note that characterized by low religiosity, they serve mainly as comparison group).

4. Discussion

Contemporary debates on the relationship between religiosity and labor market outcomes for minority women, particularly Muslim women, have highlighted a negative association. This has been attributed to several factors, including traditional-patriarchal values, limited human capital, immigration challenges, and discrimination [5,8,18,26]. The current study contributes to this discourse by introducing an additional factor—residential area, as outlined in the dual economy literature. This aspect is particularly intriguing given the tendency of ethnic enclaves to host populations with strong traditional-religious values, coupled with limited occupational opportunities [15,46]. The present study explores the combined impact of residential area and religiosity on the labor market outcomes of Arab Muslim and Christian women in Israel. While both groups live either within or outside ethnic enclaves, they differ significantly in terms of religiosity, with Muslim women typically displaying stronger religious values.

In line with findings of international research [3,5,33], the core finding emerging in the present study supported H1, particularly among Muslim women. Specifically, highly religious Muslim women were more likely to be out of the labor market or unemployed compared to less religious women. Additionally, highly religious Muslim women were less likely to hold full-time positions, to have high wages or to hold managerial positions. These associations between religiosity and employment outcomes are consistent with findings from other local studies [19,20,21], noting that an inclination towards traditional values could constitute a barrier for Muslim women’s labor market integration. In contrast, religiosity did not influence any of the employment outcomes among Christian women, suggesting that their relatively low religious identity does not hinder their labor market participation.

In partial support of H2, both Muslim and Christian women living in predominantly Jewish areas (i.e., outside their ethnic enclaves) had lower odds of not participating in the labor market (compared to being employed). Despite this, area of residence had almost no impact on the quality of employment measures for either Muslim or Christian women. Previous studies have suggested contradictory evidence on this matter [9,15]). Our research demonstrates significant associations between economic activity and residential area and shows further that residential area supplements religiosity in explaining Muslim women’s employment status. The proximity between residential areas and employment hubs in predominantly Jewish localities and the increased likelihood for contact and intercultural exchange with Jews might explain the observed association. Additionally, Arab peripheral and segregated localities are characterized by higher patriarchal, traditional and religious values compared to core/central ones (mixed or predominantly Jewish localities) [19,20,47]. Generally, Muslim Arab women living in those segregated hubs are expected to be homemakers more than are women who live in predominantly Jewish localities.

In partial support of H3, the interaction between religiosity and area of residence was significant in relation to quality measures of labor market outcomes for Muslim women, specifically concerning full-/part-time positions and wages, but not rank. These two factors interact in explaining labor market outcomes, particularly in Arab localities, as they enable Muslim women to secure better positions—those requiring long working hours and offering higher wages—reflecting a choice to advance their careers. However, the interaction effect was not observed in the case of managerial positions. These positions are already scarce, and promotions to such roles may depend on additional factors not considered in this study, such as personality and social networks. Regarding labor market participation, both religiosity and residential area were significantly associated with economic activity, though no interaction effect was found. A potential explanation for this is that religiosity, associated with patriarchal values, differs fundamentally from residential barriers, which can be overcome through financial means.

5. Conclusions

The findings suggest two main conclusions that may be applicable to other contexts as well. First, while the residential area is associated with all its residents’ labor market outcomes (expressed here in participation in employment), religiosity, as an agent-based factor, is associated with occupation measures on individual bases and hence is more related to quality measures of employment. Second, religiosity is associated with labor market outcomes of women with emphasized religious identity, whereas within groups marked by low religiosity it has a weaker effect, if any.

The study contributes to theory by providing an additional explanation for the negative associations between religiosity and labor market outcomes of women affiliated with minority groups—residential areas inside or outside ethnic enclaves. Our explanation supplements existing theories such as the tendency to traditional values, limited human capital and migration issues [3,18,31], as the social integration of women residing in ethnic enclaves appears to be more challenging. However, this account is inconsistent with discrimination theory, as women are expected to face this barrier to a lesser extent within the ethnic enclaves. The limited opportunities within these locals probably explain this contradiction.

The study contributes also to dual economy theory. It does not relate to residents of ethnic enclaves as a dichotomous measure but rather reflects their complexities [13,15]. Recent studies have addressed the diversity of ethnic groups residing in ethnic enclaves, relating to different ethno-religious background [27,28]. The current study offers a step forward by highlighting residents’ agent-based characteristics: religious identity and associations with labor market outcomes. Given these complexities, we recommend methods that incorporate both structural (e.g., residential area) and agency-based (e.g., personal choices) approaches to provide a more comprehensive understanding of employment measures like those presented by Schnell et al. [67,68,69].

Practically, government agencies and other stakeholders are advised to establish and diversify employment centers and improve accessibility for residents of segregated Arab localities, both physically and culturally, to enhance women’s participation in the labor market. Additionally, having these centers in such locations could facilitate the implementation of intervention programs aimed at improving occupational outcomes for Muslim women. The COVID-19 pandemic has altered work patterns considerably, with work from home becoming increasingly common [70,71,72]. Implementing or merging remote work possibilities in the labor market can generate more work opportunities in varied services for religious women living in ethnic enclaves, regardless of cultural, religious and geographical restrictions. This would also allow women to pursue work while balancing home and occupational requirements, hence promoting populations who are usually affiliated with lower socio-economic strata, on the one hand, and effectively contribute to their country’s economy on the other.

Importantly, at first glance these occupations suit almost only highly educated women, especially in the high-tech and finance industries. A deeper consideration, however, reveals that they also suit their less educated counterpart, including occupations such as telemarketing and service provision, mainly for Arab societies (i.e., banks, insurance companies, or health services). This work pattern bears some advantages as well as disadvantages [63,70,71,72]. However, it can basically promote the labor market participation of Arab women and even ease some barriers associated with the patriarchy. The establishment of occupational centers, as well as the expected rise in the number of women working from home, will promote the local economy currently dominated by Jewish localities.

Finally, this study covers the decade 2013–2022. Yet one cannot ignore the Israel-Gaza war ongoing since October 2023. Whereas this war is waged mainly in the Gaza Strip, its implications are felt also within Israel and extend to the labor market. We assume that the war has exacerbated suspicions between Arabs and Jews, specifically regarding those with a clear religious appearance, potentially affecting their employment, as they would encounter greater discrimination by employers on the one hand, but also might refrain from working in predominantly Jewish areas due to social exclusion on the other. Working in predominantly Jewish environments would still have its economic advantages, but it seems that under these circumstances, working in Arab localities would be more appealing.

6. Limitations and Future Directions

This study has some caveats that should be acknowledged. First, it examined employment among Muslim and Christian women residents of Arab localities or predominantly Jewish localities in Israel as separate entities. However, there are differences within each residence cluster in various measures, such as size, composition, and socio-economic status not accounted for in the present study. Second, although religiosity was measured quantitatively, a single-item measure was employed. Religiosity is a multifaceted construct that includes such factors as faith, and individual or communal practice, as well as affiliation to social circles [7,21,73]. Examining which facet affects employment among Muslim women might be a line of inquiry for future research. Third, we suspect that the limited interaction effect between religiosity and area of residence might relate to lack of statistical power. Using a larger sample from predominantly Jewish localities and of Christian women may allow future research to better address our interaction hypothesis and its underlying mechanism.

Additional avenues for further research include examining the role of religiosity and residential areas in other countries and among diverse populations. This would allow for a broader exploration of our observations in relation to other ethnic groups and countries where national conflicts do not influence interethnic relations. Furthermore, extending the research to include workplace locations (inside and outside ethnic enclaves) beyond residential areas could provide additional insights into the spatial dynamics affecting women’s employment outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.S.; methodology, H.M.A.-R.; software, Y.M.; validation, M.S. and Y.M.; formal analysis, I.S.; data curation, I.S.; writing—original draft preparation, I.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S. and H.M.A.-R.; visualization, Y.M.; supervision, H.M.A.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There was no funding for this study.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data were obtained from Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics and are available https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/cbsnewbrand/Pages/default.aspx with the permission of Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors have a conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Abdelhadi, E.; England, P. Do Values Explain the Low Employment Levels of Muslim Women Around the World? A within– and between–country analysis. Br. J. Sociol. 2019, 70, 1510–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, M.; Wilkinson, L.; Pisciotta, M.; Williams, L.S. When working hard is not enough for female and racial/ethnic minority apprentices in the highway trades. Sociol. Forum 2015, 30, 415–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, N.; Ron, J.; David, M. Human Capital, Family Structure and Religiosity Shaping British Muslim Women’s labor Market Participation. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2018, 44, 1541–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soener, M.; Godechot, O.; Safi, M. Who Benefits from Migrant and Female Labor? Connecting Wages to Demographic Changes in French Workplaces. Sociol. Forum 2023, 38, 1198–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilmaghani, M.; Dean, J. Religiosity and Female Labor Market Attainment in Canada: The Protestant Exception. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2016, 43, 244–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, N.; Johnston, R. Ethnic and Religious Penalties in a Changing British Labour Market from 2002 to 2010: The Case of Unemployment. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2013, 45, 1358–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, T. The Role of Religion, Religiousness and Religious Participation in the School-to-work Transition in Germany. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2020, 46, 3580–3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, E.; Edgell, P.; Delehanty, J. Public Religion and Gendered Attitudes. Soc. Probl. 2023, 72, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, R.; Musterd, S.; Galster, G. Neighbourhood Ethnic Composition and Employment Effects on Immigrant Incomes. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2014, 40, 710–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, A. The Labour Market Experiences and Strategies of Young Undocumented Migrants. Work Employ. Soc. 2013, 27, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R. Who Does the Dishes? Precarious Employment and Ethnic Solidarity Among Restaurant Workers in Los Angeles’ Chinese Enclave. Ethnicities 2019, 19, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H. The Territoriality of Ethnic Enclaves: Dynamics of Transnational Practices and Geopolitical Relations within and beyond a Korean Transnational Enclave in New Malden, London. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2018, 108, 756–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somashekhar, M. Neither here nor there? How the new Geography of Ethnic Minority Entrepreneurship Disadvantages African Americans. Soc. Probl. 2019, 66, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlbeck, Ö. Work in the Kebab Economy: A Study of the Ethnic Economy of Turkish Immigrants in Fin-land. Ethnicities 2007, 7, 543–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, H. Ethnic Enclaves, Self-employment, and the Economic Performance of Refugees: Evidence from a Swedish Dispersal Policy. Int. Migr. Rev. 2021, 55, 58–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; Larsson, J.P.; Öner, Ö. Ethnic Enclaves and Self-employment among Middle Eastern Immigrants in Sweden: Ethnic Capital or Enclave Size? Reg. Stud. 2021, 55, 590–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, P.; Koenig, M. Explaining the Muslim Employment Gap in Western Europe: Individual-Level Effects and Ethno-Religious Penalties. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 49, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhadi, E. The Hijab and Muslim Women’s Employment in the United States. Res. Soc. Strat. Mobil. 2019, 61, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Rabia-Queder, S. The Paradox of Professional Marginality among Arab-Bedouin Women. Sociology 2017, 51, 1084–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miaari, S.H.; Khattab, N.; Sabbah Karkabi, M. Obstacles to Labour Market Participation Among Arab Palestinian Women in Israel. Int. Labour Rev. 2020, 162, 587–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shdema, I.; Sharabi, M.; Manadreh, D.; Yanay-Ventura, G. Religiosity and Labour Market Attainments of Muslim-Arab Women in Israel. Qual. Quant. 2024, 58, 2523–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj-Yahya, N.; Aiman, S.; Nitza, K.-K.; Ben, F. An Employment Promotion Plan for the Arab Society; Israel’s Democracy Institute: Jerusalem, Israel, 2021. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Shdema, I. ‘Arabs’ Workforce Participation in Israel at a Single Municipality Scale. In Palestinians in the Israeli Labor Market: A Multi-Disciplinary Approach; Khattab, N., Miaari, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 241–261. [Google Scholar]

- Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics [ICBS]. Statistical Abstract of Israel 74; Hemmed Press: Jerusalem, Israel, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shdema, I.; Zelcowitz, I.; Sharabi, M. Views of Arab Muslims and Christians in Israel Regarding the Role of Islamization in the Interreligious Framework before and after the Arab Spring. Isr. Aff. 2022, 28, 208–231. [Google Scholar]

- Khattab, N.; Hussein, S. Can Religious Affiliation Explain the Disadvantage of Muslim Women in the British Labor Market? Work Employ. Soc. 2018, 32, 1011–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesici, M.R. Labor Market Segmentation within Ethnic Economies: The Ethnic Penalty for Invisible Kurdish Mi-grants in the United Kingdom. Work Employ. Soc. 2022, 36, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, T.M.; Platt, L. All look the same? Diversity of Labour Market Outcomes of Chinese Ethnic Group Populations in the UK. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2020, 46, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miaari, S.; Khattab, N.; Johnston, R. Religion and Ethnicity at Work: A Study of British Muslim Women’s Labour Market Performance. Qual. Quant. 2019, 53, 19–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, A.; Martin, J. Can Religious Affiliation Explain ‘Ethnic’ Inequalities in the Labor Market? Ethn. Racial Stud. 2013, 36, 1005–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseem, J.; Adnan, W. Being a Second-generation Muslim Woman in the French Labor Market: Under-standing the Dynamics of (Visibility of) Religion and Gender in Labor Market Access, Outcomes and Experiences. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2019, 61, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R.; Norris, P. Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change around the World; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Khoudja, Y.; Fleischmann, F. Ethnic Differences in Female Labour Force Participation in the Netherlands: Adding Gender Role Attitudes and Religiosity to the Explanation. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 31, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, N.; Sami, M.; Marwan, M.-A.; Sarab, A.-R.-Q. Muslim Women in the Canadian Labor Market: Between Ethnic Exclusion and Religious Discrimination. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2019, 61, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, J.; Pio, E. Veiled diversity? Workplace Experiences of Muslim Women in Australia. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2010, 27, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, J.; Weichselbaumer, D. “Just Take it Off, Where’s the Problem?” How Online Commenters Draw on Neoliberal Rationality to Justify Labour Market Discrimination Against Women Wearing Headscarves. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2022, 45, 2157–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joppke, C. Limits of Integration Policy: Britain and Her Muslims. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2009, 35, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.C. Ethnic Controlled Economy or Segregation? Exploring Inequality in Latina/o Co-Ethnic Jobsites. Sociol. Forum 2009, 24, 589–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, H.S. Selective Moving Behaviour in ethnic Neighbourhoods: White Flight, White Avoidance, Ethnic Attraction or Ethnic Retention? Hous. Stud. 2017, 32, 296–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, A.; Candipan, J. Racial/Ethnic Transition and Hierarchy Among Ascending Neighborhoods. Urban Aff. Rev. 2019, 55, 1550–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamuk, A. Geography of Immigrant Clusters in Global Cities: A Case Study of San Francisco. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2004, 28, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edin, P.-A.; Fredriksson, P.; Åslund, O. Ethnic Enclaves and the Economic Success of Immigrants—Evidence from a Natural Experiment. Q. J. Econ. 2001, 118, 329–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiles, C.H.; Rodriguez, C.L.; Galbraith, C.S. The Impact of Ethnic-Religious Identification on Buyer-Seller Behaviour: A Study of Two Enclaves. Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2007, 1, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, I.; Sabagh, G.; Bozorgmehr, M.; Der Martirosian, C. Internal ethnicity in the ethnic economy. Ethn. Racial Stud. 1993, 16, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H.-S. A Liability of Embeddedness? Ethnic Social Capital, Job Search, and Earnings Penalty Among Female Immigrants. Ethnicities 2018, 18, 385–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Z. Residential and Industrial Enclaves and Labor Market Outcomes among Migrant Workers in Shenzhen, China. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2022, 48, 750–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shdema, I.; Abu-Rayya, H.M.; Schnell, I. The Interconnections Between Socio-Spatial Factors and Labour Market Integration Among Arabs in Israel. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2019, 98, 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smooha, S. The Model of Ethnic Democracy: Israel as a Jewish and Democratic State. Nations Natl. 2002, 8, 475–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smooha, S. Ethnic Democracy: Israel as an Archetype. Isr. Stud. 2005, 2, 198–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabi, M. Political Economy and Work Values: The Case of Jews and Arabs in Israel. Isr. Aff. 2014, 20, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabi, M.; Shdema, I.; Manadreh, D.; Tannous-Haddad, L. Muslim Working Women: The Effect of Cultural Values and Degree of Religiosity on the Centrality of Work, Family, and Other Life Domains. World 2025, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Atawneh, M.; Ali, N. Islam in Israel: Muslim Communities in non-Muslim States; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hatina, M.; Muhammad, A.-A. Muslims in a Jewish State: Religion, Politics, Society; Hakibutz Hameuhad: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2018. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Yonay, Y.P.; Yaish, M.; Kraus, V. Religious Heterogeneity and Cultural Diffusion: The Impact of Christian Neighbors on Muslim and Druze Women’s Participation in the Labor Force in Israel. Sociology 2014, 49, 660–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, N. Ethnic and Regional Determinants of Unemployment in the Israeli Labor Market: A Multilevel Model. Reg. Stud. 2006, 40, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, I.; Shdema, I. Commuters’ and Localists’ Styles of Socio-spatial Segregation in Three Types of Arab Communities in Israel. J. Earth Sci. Eng. 2014, 4, 651–666. [Google Scholar]

- Shdema, I.; Martin, D.G.; Abu-Asbeh, K. Exposure to the Majority Social Space and Residential Place Identity Among Minorities: Evidence from Arabs in Israel. Urban Geogr. 2021, 42, 507–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, N.; Sami, M. (Eds.) Palestinians in the Israeli Labor Market: A Multi-Disciplinary Approach; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin-Epstein, N.; Semyonov, M. Modernization and Subordination: Arab Women in the Israeli Labor Force. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 1992, 8, 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Haidar, A.; Lewin-Epstein, N.; Semyonov, M. The Arab Minority in Israel’s Economy: Patterns of Ethnic Inequality. Contemp. Sociol. A J. Rev. 2019, 23, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, I.; Shdema, I. The role of Peripheriality and Ethnic Segregation in Arabs’ Integration into the Israeli Labor Market. In Inequalities in Contemporary Israel; Hayya, S., Nabil, K., Sami, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 223–238. [Google Scholar]

- Sharabi, M.; Shdema, I.; Abboud-Armaly, O. Nonfinancial Employment Commitment Among Muslims and Jews in Israel: Examination of the Core–Periphery Model on Majority and Minority Groups. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2020, 43, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams-Harmon, D.; Lewis, A.; Yun, J.A. Challenges for Creating Resilience in Minorities and Female Workers, and the Role of Flexibility in Work Environments: A Mixed Method Study. Socioecon. Chall. 2024, 8, 88–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, N. Ethnicity and Female Labour Market Participation: A New Look at the Palestinian Enclave in Israel. Work Employ. Soc. 2002, 16, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, V.; Yonay, Y.P. Facing Barriers: Palestinian Women in a Jewish-Dominated Labor Market; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Erdfelder, E.; Faul, F.; Buchner, A. GPOWER: A general power analysis program. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 1996, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, A.B.; Shdema, I.; Schnell, I. Arab Integration in New and Established Mixed Cities in Israel. Urban Stud. 2021, 59, 1800–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, I.; Diab, A.A.B.; Benenson, I. A Global Index for Measuring Socio-Spatial Segregation Versus Integration. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 58, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shdema, I.; Haj-Yahya, N.; Schnell, I. The Social Space of Arab Residents of Mixed Israeli Cities. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2018, 100, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beland, L.-P.; Brodeur, A.; Wright, T.; Tyrowicz, J. The short-term economic consequences of COVID-19: Exposure to disease, remote work and government response. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0270341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Moen, P. Working more, less or the same during COVID-19? A mixed method, intersectional analysis of remote workers. Work Occup. 2022, 49, 143–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, P.M.; Parker, S.H.; Shen, R. How remote work changes the world of work. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2024, 11, 193–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhadi, E. Religiosity and Muslim women’s employment in the United States. Socius 2017, 3, 2378023117729969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).