Abstract

This study explores the cultural, productive, territorial, and organizational practices of cacao-producing families in Lebrija, Santander (Colombia), within the broader context of rural sustainability and peasant identity in Latin America. In response to recent national and international frameworks recognizing the rights of peasants, the research aims to document local knowledge systems and community-based strategies that sustain rural livelihoods. Through a qualitative ethnographic approach, including participatory workshops, semi-structured interviews, and social cartography, the study collected narratives, practices, and territorial dynamics over the course of one year. The results reveal that cacao production is not only an economic activity, but a deeply embedded cultural process that intertwines with memory, family ties, lunar cycles, and environmental stewardship. Participants described conflicts related to water access, deforestation, poultry farming, and the expansion of urban infrastructure. Despite these pressures, families demonstrated adaptive capacities through agrodiversity, traditional knowledge, and associative work. The study concludes that these cacao-based practices offer valuable insights into bottom-up strategies for resilience and territorial sustainability and calls for greater inclusion of peasant knowledge in rural development agendas.

1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been growing recognition at both national and international levels of the need to protect and value the rights, identities, and knowledge systems of rural populations, especially those engaged in small-scale agriculture [1,2,3,4]. The 2018 Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas, adopted by the United Nations, was a milestone in acknowledging the historical marginalization of rural communities and the essential role they play in food sovereignty, biodiversity conservation, and cultural continuity [5]. That same year, in Colombia, the Constitutional Court ordered the elaboration of a technical document that would formally define and characterize the peasant population. The resulting publication, Conceptualización del Campesinado en Colombia [6], laid the groundwork for understanding the multiple dimensions of campesino life, namely territorial, cultural, productive, and organizational.

While this framework offers a valuable starting point, it also admits its limitations in capturing the full complexity of rural realities across diverse territories. Scholars have since pointed out the need to complement such frameworks with grounded, localized studies that can reveal the nuanced ways in which rural families navigate socio-environmental challenges, sustain their livelihoods, and reproduce cultural practices over time [7,8,9]. In this context, cacao-producing communities in Colombia represent an emblematic case, given the crop’s economic significance, ecological relevance, and cultural embeddedness [2,10,11]. However, the lived experiences, traditional knowledge, and socio-environmental adaptations of these communities remain underexplored in the academic literature, especially in relation to the dynamic tensions between agricultural modernization and ancestral practices [12,13].

This study contributes to bridging this gap by examining the cultural practices, environmental relationships, and community dynamics of cacao-producing families in Lebrija, Santander, a municipality located in northeastern Colombia. By focusing on the subjective dimensions of rural life—memory, identity, ecological knowledge, and associative work—we aim to highlight how campesino families co-construct their territories in the face of changing environmental, infrastructural, and market pressures. Through a participatory, ethnographic approach, this research provides insights into bottom-up processes of sustainability and resilience that challenge the homogenizing effects of top-down rural development models [14].

Ultimately, the goal of this work is to offer a grounded perspective on how campesino identity is enacted and negotiated through daily practices in cacao cultivation, territorial management, and community interaction. The study’s findings suggest that sustainability in rural Colombia cannot be achieved without recognizing and incorporating the diverse cultural and environmental knowledges that shape rural livelihoods.

2. Theoretical Dimensions for the Characterization of Cultural Practices

To understand the cultural practices of cocoa-producing families in Lebrija, the research adopted an analytical framework based on four interconnected dimensions: territorial, productive, organizational, and symbolic memory. This structure draws on the methodological and conceptual contributions of the Conceptualización del Campesinado en Colombia [6], and aligns with Latin American theoretical approaches to rurality and agroecological knowledge [7].

Territorial dimension: This refers to the dynamic relationship between peasant families and their environment, especially their interaction with land, water, forests, and fauna. It captures how the territory is experienced, transformed, and narrated. Particular attention is given to the impact of the Green Revolution and the push for agricultural modernization in Colombia since the 1970s, which promoted the adoption of technological packages and displaced traditional knowledge [9,15,16].

Productive dimension: This dimension explores cocoa cultivation as the backbone of rural life, not only in economic terms but also as a form of cultural expression and intergenerational learning. It includes the plant’s life cycle, the agricultural calendar, and practices influenced by lunar phases, traditionally embedded in local knowledge systems [17,18].

Organizational dimension: This focuses on the ways in which rural families organize collectively to manage resources, promote cooperation, and exercise autonomy. These forms of organization range from informal networks to local associations and communal assemblies. They play a key role in shaping social cohesion and resilience in peasant territories [19].

Symbolic-memory dimension: This dimension addresses the symbolic meanings of cocoa as a cultural object and vehicle of memory. It includes traditional uses of the fruit (culinary, medicinal, ritual) and the oral narratives passed down across generations. These practices contribute to collective identity and the active reconstruction of memory as a form of resistance and persistence [20,21].

The articulation of these dimensions allowed for a multidimensional analysis of peasant identity and practice in the context of cocoa production, enabling deeper insight into how cultural knowledge is transmitted, transformed, and defended in rural Colombia.

3. Materials and Methods

This research was conducted over the course of one year using a qualitative ethnographic approach, structured around four analytical dimensions: territorial, productive, organizational, and symbolic memory. The methodological design integrated participatory workshops, semi-structured interviews, and non-participant observation, carried out in both urban and rural areas of the municipality of Lebrija, Santander (Colombia). These methods aimed to document the situated knowledge, practices, and socio-environmental relationships of smallholder cacao-producing families, while ensuring community involvement throughout the research process.

Two initial participatory workshops were conducted at the “Casa de la Cultura” in the urban center of Lebrija with cacao farmers affiliated with the “Misión Chocolate” association. These gatherings served as both a first point of contact with participants and a space for collective reflection on their experiences. In parallel, two additional workshops were held in the rural villages of La Victoria and San Nicolás. These were complemented by five field visits to different farm sites, during which fourteen in-depth semi-structured interviews were carried out with smallholder cacao-producing families. The interviews focused on farming practices, collective memory, and identity narratives related to cacao cultivation.

The participatory methods used in this study were based on the Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) approach, originally developed to promote inclusive, community-led planning in rural development contexts [14,22,23,24]. PRA was selected due to its emphasis on recognizing local knowledge, empowering communities to analyze their own realities, and facilitating shared decision-making, principles that align closely with the goals of this research. Specifically, we adapted two tools from a regional PRA guide developed by INSFOP, FAO, and PESANN (2008): the historical production timeline and social cartography [25]. These tools allowed participants to visually reconstruct key environmental, productive, and territorial changes over time and space.

In addition to these, two tools, the “Cocoa Anatomy” and the “Cocoa Biography”, were co-designed to address the need for culturally grounded, context-sensitive instruments. These participatory techniques encouraged in-depth dialogue among farming families, helped surface intergenerational knowledge, and supported the identification of locally meaningful categories of analysis for cocoa production and land management.

The participatory nature of the workshops enabled a deep and reciprocal dialogue on the cultural practices of farming families. Each household contributed their knowledge and experiences, fostering mutual learning and the construction of shared meaning. The visual component of the tools facilitated participants’ engagement with the process and supported collective decision-making, in line with the principles outlined in participatory development approaches [26].

The overall methodological approach prioritized horizontality and reciprocity in the research process. Rather than treating farming families as research subjects, the project positioned them as active participants in the co-construction of knowledge. Through participatory rural and community workshops, families were engaged in collective reflection, analysis, and meaning making related to their cultural practices, environmental management, and cacao cultivation. This dialogical process allowed for the articulation of diverse perspectives and helped ensure that local knowledge systems were not only recognized but integrated as valid frameworks for understanding rural sustainability. The researcher–community relationship was intentionally structured to promote trust, respect, and mutual learning. The fieldwork was designed to create shared spaces for interaction, in the farms, on the trails, around the table, where participants could speak from lived experience and guide the research team through their own rhythms and landscapes. As emphasized in recent studies [27,28,29], participatory methodologies that emerge from direct interaction foster more integrative results by respecting, articulating, and building upon local knowledge.

Field activities were designed to promote close engagement with farming families and their everyday environments. Researchers joined participants on guided walks through cocoa plantations, during which families described key practices related to crop care, pest control, and harvesting decisions. These visits extended into the surrounding veredas (Vereda is a term used in Colombia to designate rural subdivisions within municipalities. These areas typically consist of dispersed smallholder farms, local infrastructure (such as schools or chapels), and shared community life. The concept holds both administrative and cultural significance in rural planning), where researchers observed water sources, land use patterns, and spatial connectivity between farms.

Rather than remaining as external observers, the research team participated in shared routines like eating meals together, staying overnight when invited, and starting the day alongside families, with the aim of creating a setting of mutual trust. This immersive presence enabled access to experiential knowledge that is often tacit or embodied, and allowed for the recognition of subtle dynamics in land management and community life that might otherwise remain invisible in conventional interviews.

Participant recruitment was carried out in collaboration with “Misión Chocolate”, a local association of cocoa producers based in Lebrija. The organization serves as a hub for technical support and farmer training, and was instrumental in identifying families engaged in small-scale, family-based cacao agriculture. Three main criteria guided participant selection: (1) affiliation with Misión Chocolate; (2) involvement in peasant family farming centered on cocoa production; and (3) willingness to participate actively in the research process.

From those who attended the participatory workshops, twelve farms were selected for in-depth rural visits and non-participant observation. Selection prioritized geographic diversity across the municipality to capture territorial variation, and placed particular emphasis on the inclusion of women farmers, especially in households engaged in post-harvest transformation activities, tasks which are often led by women in these communities [30,31,32,33].

3.1. Rural Workshops

Two rural workshops were conducted in the villages of La Victoria and San Nicolás, designed to explore participants’ historical, environmental, and productive knowledge through interactive group activities. Two core participatory tools were used:

- Historical Production Timeline: Participants collectively constructed a timeline divided into three key periods, before 1970, from 1970 to 2000, and from 2000 to the present, corresponding to major agricultural and socio-political shifts in Colombia. The 1970s were used as a baseline to reflect the impact of Green Revolution technologies on rural economies. Within each period, participants qualitatively assessed variables such as water availability, forest coverage, crop types, and land management strategies, assigning scores on a collective scale from 0 (lowest) to 5 (highest). These scores reflect the relative presence of each element in the territory during the indicated period.

- Cocoa Biography: This tool mapped the life cycle of the cocoa plant, from seed preparation to grafting, peak productivity, and senescence. At each stage, participants described associated practices, beliefs, and forms of knowledge. The exercise also included a circular diagram divided by lunar phases (new, waxing, full, waning) to identify how moon cycles influence farming decisions and symbolic interpretations of plant behavior.

3.2. Participatory Urban Workshops

Two participatory workshops were also held in the urban center of Lebrija, bringing together cocoa-producing families from different veredas to collectively reflect on their identities, knowledge systems, and territorial dynamics.

- Introductory Workshop: This session presented the research objectives and methodological approach. Participants were grouped by vereda and invited to create symbolic self-representations using a silhouette drawing technique. Each person illustrated or wrote on individual cards key elements related to their identities as cocoa producers and the cultural practices embedded in their everyday lives.

- Workshop on the Four Dimensions: The second session focused on the four core analytical dimensions—territorial, productive, organizational, and symbolic memory—through a set of visual and participatory tools:

- a.

- Social Cartography: Participants drew community maps to represent their spatial understanding of the territory.

- b.

- Network Cartography: Using a different color, they added gathering spaces and local social associations to the same maps.

- c.

- Cocoa Biography: This tool was revisited to further explore the productive dimension in more detail.

- d.

- Cocoa Anatomy: Participants mapped the various uses of the cocoa plant like culinary, medicinal, and symbolic, revealing intergenerational knowledge and memory embedded in everyday practices.

All information collected through these tools was analyzed qualitatively, with the voices and interpretations of participants serving as the central axis of the narrative.

3.3. Data Systematization and Analytical Framework

The material generated through workshops, interviews, and field visits was organized and analyzed using a qualitative, dimension-based matrix. The matrix was structured around the four analytical dimensions—territorial, productive, organizational, and symbolic memory—and expanded through emerging subcategories derived from the participants’ own narratives. These included the history of each family and vereda, cultivation and care practices, environmental transformations, socio-political challenges, and localized forms of conflict and resistance.

This analytical framework allowed for a contextualized interpretation of rural knowledge systems, highlighting both common patterns and site-specific strategies developed by cacao-producing families to sustain their territories, practices, and identities. It is important to mention that although participants in rural and urban workshops could have different backgrounds and trajectories, comparability was ensured by applying the same participatory tools in all settings and by using common selection criteria (smallholder cocoa producers affiliated with Misión Chocolate). All data were subsequently integrated into a single analytical matrix based on the four dimensions (territorial, productive, organizational, and symbolic memory), allowing us to examine both convergences and contrasts within a consistent framework and ensuring that variations reflected contextual realities rather than methodological inconsistencies.

4. Results

4.1. Territorial Dimension

In this study, territory is understood as a space socially constructed by its inhabitants, who develop most of their political, economic, and social life within it [6,34,35]. Based on this perspective, the analysis of the territorial dimension focused on four interrelated axes: territorial organization, water and forest systems, productive land use, and environmental conflicts.

To support this analysis, participants co-created a territorial map during the rural workshops. This map reflects their understanding of infrastructure, ecological zones, cultivation areas, and socio-environmental tensions across the veredas. As shown in Figure 1, the map served not only as a diagnostic tool but also as a spatial narrative of how farming families perceive and manage their territory. It allowed participants to position themselves geographically, identify shared assets, and recognize overlapping or disputed areas, which later informed the thematic axes of the analysis.

Figure 1.

Participatory social cartography of cocoa-growing territories in Lebrija. Note: The image was created based on data provided by participants during rural workshops. It reflects their own territorial knowledge and experiences.

4.1.1. Territorial Organization

Connectivity plays a key role in how rural families structure and inhabit their territory. The main road linking Lebrija to Barrancabermeja is seen as a lifeline that facilitates both local and regional trade. As one participant noted: “We are aiming for an extended trade, so the road lets us move our goods in suitable times and conditions.” This infrastructure, though not always in ideal condition, is central to the region’s agricultural viability.

While the presence of multiple rural roads was viewed as a positive factor— “Fortunately, Lebrija has several rural roads”—some residents raised concerns about the proliferation of informal trails, or “ramales”, which have increased the risk of theft by enabling discreet and rapid movement. In response to these safety concerns, communities have developed informal surveillance systems using mobile phones and WhatsApp groups to share real-time updates about unfamiliar individuals or suspicious activity. These mechanisms of local control reflect both the challenges and the resilience of community-based territorial governance.

A particularly illustrative case is that of Ricaurte. Although it is not officially recognized as a vereda due to the absence of a legally constituted Community Action Board, its inhabitants identify themselves as a distinct community and actively participate in meetings of neighboring veredas such as San Joaquín and Sardinas. This emphasizes the disjunction between formal territorial classifications and lived spatial identities in rural Colombia. Residents’ sense of place and collective organization often exceed or bypass administrative definitions.

These dynamics of road-based connectivity, informal surveillance, and spatial identity construction are visually represented in Figure 1, where participants mapped not only infrastructure but also the social and territorial affiliations that shape their everyday navigation of space. The map reveals how vereda boundaries, trade routes, and zones of cooperation or conflict are experienced and reconstructed by rural families themselves.

4.1.2. Water and Forests

Water sources and forest cover are perceived by participants as vital to the sustainability of both life and agricultural production. Key water bodies include the San Joaquinera and La Aguirre creeks, along with the Lebrija River, which also serve as natural boundaries between veredas (see Figure 1). The San Joaquinera, in particular, is referred to as “the life of these veredas,” as it supplies water to the majority of farms in the area. Participants traced its origin to a small forest patch near the Brisas restaurant, where they described a natural reservoir affectionately known as “una esponjita de agua” (a little sponge of water). From there, the creek joins other tributaries, forming a network that sustains rural households across multiple communities.

This intimate relationship with water is not only ecological but also spiritual and symbolic. Participants shared practices such as sembrar el agua (“planting water”), a ritual involving the burial of a calabash (totumo) filled with holy water, often accompanied by icons of the Virgin of Health. These rituals, especially common in La Victoria and Ricaurte, were described as collective acts of protection against landslides and droughts, underscoring a worldview in which hydrological systems are seen as both sacred and fragile.

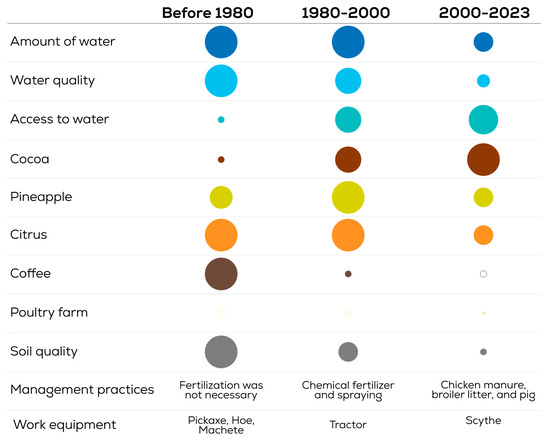

The connection between trees and water was repeatedly expressed in the phrase “where there are trees, there is life.” Most families intentionally preserve forest patches on their farms to retain soil moisture, support biodiversity, especially pollinators, and protect local microclimates. However, concerns about water quality have intensified, as presented in Figure 2. Participants reported increasing contamination in surface streams, prompting a shift toward the use of private springs and improvised collection systems.

Figure 2.

Timeline of key territorial changes in Lebrija (Participatory Mapping). Note: This figure was created by the research team based on data provided by participants during co-creation workshops. Circle size represents relative importance, on a scale from 0 (smallest circle) to 5 (largest circle). Scores reflect the relative presence of each element in the territory during the indicated period. Management practices shown in this figure reflect only those explicitly mentioned by participants during the participatory workshops. Their absence in a given period does not necessarily imply the complete lack of such practices in the region but indicates that they were not emphasized in the collective narratives constructed by participants.

These environmental, cultural, and infrastructural changes were explored through a participatory timeline exercise, summarized in Figure 2. Participants evaluated the presence and relative importance of key territorial elements across three historical periods: before 1970, from 1970 to 2000, and from 2000 to the present. Forest cover, for instance, was perceived to decline sharply after the introduction of Green Revolution technologies, while the issue of water contamination gained prominence in recent decades. As shown in the lower rows of Figure 2, these trends are not only remembered but also interpreted by communities as symptoms of broader territorial transformations, linking ecological shifts to agricultural modernization and institutional neglect.

4.1.3. Productive Systems

Cocoa remains the backbone of most agricultural systems in Lebrija, especially in communities like Ricaurte and La Victoria. While some farms are dedicated entirely to cocoa, many adopt diversified agroecosystems that combine cocoa with maize, citrus, avocado, plantain, and timber species. This strategy, described by participants as a balance between a “big box” (cocoa) and several “small boxes” (subsistence crops), reflects a logic of resilience against market volatility, pest outbreaks, and climate uncertainty.

Although intercropping cocoa with citrus has sparked occasional debate—some farmers believe that citrus trees negatively affect cocoa growth—many families adapt their practices based on localized knowledge and observed outcomes. This capacity to adjust productive strategies is grounded in empirical observation and intergenerational learning rather than prescriptive agronomic models.

Beyond economic logic, this mixed-crop model reflects a cultural vision of food sovereignty and autonomy. As one farmer explained: “Life in the countryside is beautiful: if you want fish, you go and catch one; if you need meat, you grab a chicken. Everything is right there on the farm.” This worldview places the household not just as a unit of production, but as a living space where ecological, social, and symbolic needs are met simultaneously.

This approach contrasts with other smallholder cocoa systems, such as in the “rancherías” of southern Mexico, where the advance of an enclave economy centered on cocoa has displaced traditional crops and deepened household vulnerability [36,37,38]. In contrast, the productive strategies in Lebrija illustrate how diversified peasant agriculture can sustain both livelihoods and cultural identities, while buffering against external shocks.

4.1.4. Environmental Conflicts

The sustainability of cocoa-growing territories in Lebrija is increasingly threatened by overlapping environmental pressures, many of which stem from land use conflicts and unregulated economic activities. Among the most recurrent concerns is the expansion of deforestation, primarily associated with cattle ranching and, more recently, with the advance of pineapple monoculture in Sardinas. The latter depletes soil nutrients and undermines the long-term viability of agroecological systems.

However, the most critical and contested conflict identified by participants relates to the proliferation of industrial poultry farms (galpones), particularly in the communities of San Joaquín and, more recently, Cútiga. Residents reported that these facilities discharge untreated wastewater into the San Joaquinera creek, one of the main water sources in the area, leading to significant pollution and a sharp increase in fly populations. As one resident lamented: “We’ve even sued them, but they always win.” The contamination not only affects environmental health but also disrupts daily life and public health conditions in surrounding households. These accounts are consistent with wider evidence showing that industrial poultry farms contribute to water eutrophication, odor problems, and pest proliferation, especially when waste is poorly managed [39].

This conflict is further compounded by inequitable water usage. According to participants, poultry operations extract large volumes of water upstream while returning it contaminated downstream, severely affecting neighboring communities’ access to clean water. One parent noted: “The poultry farms leave us without water; even the kids at school go without.” This upstream–downstream dynamic has created social tensions and reflects deeper asymmetries in resource control.

Beyond poultry farming, other industrial activities have also left their mark. A notable incident involved a chemical spill from a nearby processing plant, which caused the complete die-off of aquatic life in the Angula creek. Participants cited this event as a turning point in community awareness regarding industrial accountability and environmental vulnerability.

Urban sprawl and rural “parcelización” (the subdivision of land into small lots for residential construction) have accelerated in recent years due to population growth and the expansion of Bucaramanga’s urban frontier. This process has intensified pressure on local water systems, with notable effects on water availability, runoff, and land degradation. Like broader global patterns, participants in Lebrija described how increasing impermeable surfaces and construction in recharge zones have led to altered hydrological cycles and greater exposure to both drought and flooding events. These observations are consistent with research showing that urban sprawl contributes to land degradation, disrupts aquifer recharge, and increases flood risk and water pollution [40,41,42,43,44,45].

Moreover, poor waste management and the intensive use of agrochemicals in peri-urban zones have exacerbated local water contamination, aligning with evidence that urbanization amplifies the concentration of nitrogen, phosphorus, and suspended solids in water bodies [46,47]. These cumulative impacts heighten ecological vulnerability while disproportionately affecting rural households who depend on local springs and surface water for domestic and agricultural use.

Infrastructure development, including the widening of the Barrancabermeja road, has also contributed to the disruption of natural water sources. Although these projects provide employment, residents expressed concern over the long-term ecological impacts: “These springs will burst out again elsewhere,” warned one participant, referring to the unintended redirection of underground flows. Several families have been forced to install gravity-fed pipelines or improvised pumps due to the declining flow of local streams.

Finally, residents linked recent climatic instability to the construction of the Topocoro Dam. Increased humidity has favored the spread of monilia fungus, severely affecting cocoa yields, especially in areas close to the reservoir. Other crops such as soursop (guanábana) and lime have also suffered, as excessive moisture disrupts pollination and flowering cycles. Despite these challenges, many households have adapted through experience, observation, and collaborative problem-solving, echoing broader regional patterns of peasant resilience in the face of environmental uncertainty [19].

4.2. Organizational Dimension

Peasant families in Lebrija build dense networks of familial and community-based relationships that serve as key mechanisms for accessing resources, services, and markets. These relationships are not limited to kinship but extend to neighbors, associations, and informal networks that shape collective action in the territory. In the case of cocoa-producing households, one of the most visible organizational references is the Misión Chocolate association, which supports both the production and transformation of cocoa. However, understanding the organizational fabric of these communities requires a closer look at their basic infrastructure, meeting places, and associative dynamics.

4.2.1. Infrastructure and Meeting Points

The availability of infrastructure varies considerably between veredas. In La Victoria and Conchal, for example, the presence of local cemeteries, a rare feature in rural Santander, signals a deep-rooted sense of belonging that transcends life itself. La Victoria also stands out for having a school and a Catholic parish, making it one of the best-equipped veredas in terms of community infrastructure. Sardinas has a chapel and a school, while other settlements such as Cútiga, Zaragoza, Filo de Cruces, and San Joaquín rely solely on small rural schools.

These facilities serve multiple roles: they are not just physical spaces, but nodes of social life. In La Victoria, the parish doubles as a venue for civic programs like the School for Parents, coordinated by the local school. Similarly, Don Floro’s shop, beyond being a place to buy supplies, functions as an informal gathering point, and is often offered for use during workshops, health brigades, or training sessions. It is the only small convenience store (micromarket) in La Victoria, selling basic groceries and everyday household products for the community, rather than agricultural inputs.

In San Joaquín, a vereda that also receives residents from neighboring Ricaurte, the school serves as the main communal space. It hosts religious masses, meetings of the Junta de Acción Comunal (JAC), and assemblies for the local aqueduct system. Across most veredas, the rural school plays this central role, becoming the de facto headquarters for community life and decision-making.

In areas lacking public infrastructure, private homes or centrally located farms often fulfill this role. A case in point is El Manantial, a farm in San Nicolás Alto that has hosted training sessions from public institutions such as SENA and ASOFRUCOL, demonstrating how private actors step in to fill institutional gaps.

4.2.2. Associations and Market Dynamics

Local organizational efforts in Lebrija have faced a complex trajectory. Participants from Ricaurte recalled ASCAMBEL, an association that once brought together producers of various crops to access projects and strengthen local commercialization. However, the migration of its young leaders in search of employment elsewhere eventually led to the group’s dissolution. One farmer described this asymmetry using a metaphor: “It’s like tying up a donkey and letting the tiger loose to devour it. They call it a peasant market, but it isn’t really. That’s the problem.”

This statement reveals the frustration experienced by small-scale producers who face systemic disadvantages in accessing markets. Many sell unprocessed cocoa at low prices, only to buy it back as finished chocolate at much higher costs. The price of inputs frequently exceeds revenues, and without value addition or collective bargaining power, smallholders often operate at a net loss. These realities underscore the structural inequalities embedded in rural economies and highlight the urgency of strengthening associative processes [48].

Within this context, Misión Chocolate appears as the only active local association, although with limited reach. Participants noted that meetings are usually held at the Casa de la Cultura, “whenever Don Antonio invites us.” Beyond this space, other points of exchange include the municipal coliseum, where farmers receive government-provided supplies, and informal commercial hubs such as El Cafetero or the property of Don Carlos Ferrer, where cocoa is bought and sold. While these spaces are dispersed and often improvised, they contribute to a decentralized but meaningful network of social and economic coordination.

Yet, the limited scope of local associations also points to an area that could benefit from further strengthening. Although organizational aspects were not the main focus of this research, the findings suggest that stronger institutional and community support could translate into tangible benefits for farmers. For example, during workshops, farmers noted that organic cacao was often sold at the same price as conventionally produced cacao, which diminished the incentive to adopt sustainable practices. A collective initiative to obtain clean production or sustainability certifications could help secure better prices and make the benefits of associativity more tangible. This is not a core axis of our analysis, but it does highlight a possible direction for future research and action.

Despite these efforts, several challenges persist. Youth migration continues to weaken associations, collective commercialization remains limited, and unequal competition with large-scale producers undermines local initiatives. These trends reflect broader processes of rural fragmentation [49]. Strengthening associative work, fostering intergenerational collaboration, and securing institutional support are essential steps toward strengthening organizational resilience and building fairer market access for rural producers.

4.3. Productive Dimension

In Lebrija, cacao cultivation is not merely an agricultural activity but a core component of peasant livelihoods, intimately woven into economic, ecological, and cultural life. While some households sell dried beans as their primary income, others engage in artisanal processing to produce chocolate bars, bonbons, and hot chocolate tablets. This dual approach reflects the diversity of livelihood strategies and varying degrees of market integration among smallholder families.

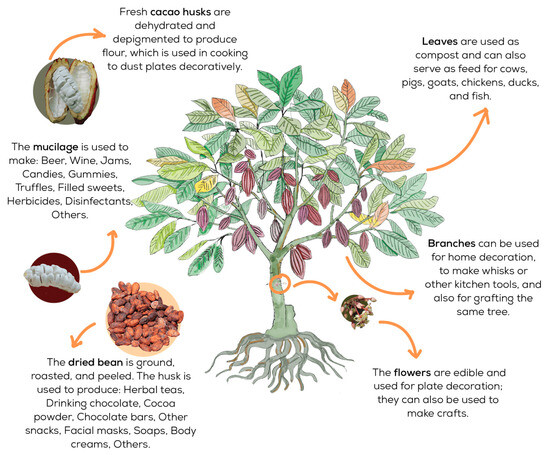

Cacao is central to the identity of the region’s rural population. Families frequently refer to themselves as “cacaoteros”, and the entire cacao life cycle, from seed to processing, is embedded in their daily practices, oral knowledge, and intergenerational transmission of techniques. This was documented visually through two co-created illustrations that portray the biography and anatomy of cacao (see Figure 3 and Figure 4). These images synthesize local knowledge on plant development, care, and productive use.

Figure 3.

Cacao biography according to producers from Lebrija. Note: Image co-designed with participants during co-creation workshops, depicting the cacao life cycle from seed to value-added product.

Figure 4.

Anatomy of the cacao tree according to local knowledge. Note: Drawing created based on participant knowledge about the structure and functions of cacao plant components.

4.3.1. Seed Selection and Germination

Although most families now rely on grafted seedlings from external sources, traditional knowledge around seed selection remains alive and valued. For many, the first step is identifying the right tree: a productive specimen shows pods of different sizes, while a “harvest tree” yields uniform pods. Farmers prefer pods taken from the main branches over those from the trunk or terminal branches, based on the belief that these provide stronger and more fruitful descendants. Seeds are extracted from the pod’s center, cleaned of mucilage using rusque (fine sawdust), and germinated in dark, humid conditions, often beneath a bed or under layers of wet newspaper. This germination technique, known as “tallar la Semilla”, is considered fundamental to securing healthy and vigorous plants.

4.3.2. Transplanting and Grafting

Once germinated, the seedlings are transferred into bags filled with soil, sand, and compost for about two months before transplantation. Older farmers recall traditional methods involving 40 × 40 cm holes filled with decomposed organic matter, left to “cool” for 20 days. Though newer planting techniques tend to simplify this step, some families still prefer the older method, convinced of its benefits for root development and long-term productivity.

Grafting has become a near-universal practice to enhance yield and disease resistance. Techniques such as malayo, pechito a pechito, and parche (budding) are selected based on the thickness and age of the trunk. These procedures demand careful timing and are guided by deeply symbolic notions. Participants likened the matching of sap between branches to human blood transfusions: “the sap has to match, like blood in humans”.

4.3.3. Agroecological Management and Planting Design

The spatial design of cacao planting reflects both topographic conditions and agroecological principles. Farmers alternate between triangular, rectangular, and terrace layouts, depending on the slope and soil drainage. Cacao trees are commonly interspersed with plantains or “mata ratón” (Gliricidia sepium), which provide shade, retain soil moisture, and contribute to ecological diversification.

This intercropping strategy also reflects an economic rationale: cacao is the big box, the primary income source, while other crops like maize, bananas, and medicinal herbs are small boxes that ensure household food security. As one participant summarized, “everything is on the farm”, from poultry and fish to cassava and fruit, emphasizing the multifunctionality of the agroecosystem and its capacity to withstand market fluctuations.

4.3.4. Pruning, Fertilization, and Flowering

Pruning and fertilization practices are central to tree health. A well-managed canopy, trimmed into a pentagon, facilitates airflow and sunlight exposure, reducing disease risk. Farmers frequently highlighted their preference for organic compost instead of chemical fertilizers, framing it as a practice more consistent with their vision of sustainable farming. A notable cultural practice known as “condoniar” involves covering young trees with sacks to protect them from herbicide drift during weeding.

Flowering begins roughly one year after planting, but early pods are often removed to avoid “ensutar la mata”, a term used to describe the weakening of a tree forced to fruit too soon. Natural pollination by midges supports fruit set, which is celebrated as a sign of vitality. Harvest readiness is assessed through traditional indicators such as color and sound: “if it sounds hollow, it’s ready; if it’s solid, it’s not.”

4.3.5. Harvesting and Post-Harvest Processing

Harvesting is performed with scissors to avoid damaging the “almohadilla floral” (floral cushion), a sensitive part of the plant that ensures future fruiting. Pods are opened manually, and the seeds are removed and placed in fermentation boxes lined with banana or bijao (Calathea lutea) leaves. The fermentation process typically lasts six days, with daily mixing to ensure even heat and flavor development.

Drying takes place in “casa elba” systems, wooden trays with retractable roofs, or using tendales (cloth nets) under the sun. In families without dedicated infrastructure, sun drying remains a viable option. Some participants even recalled ancestral beliefs that cacao, when warm and freshly harvested, could pull out sickness from children when used to wrap them, a vivid reminder of the symbolic and medicinal place of cacao in rural life.

4.3.6. Disease Management and Tree Renewal

Properly managed cacao trees can remain productive for over 50 years. Farmers monitor for diseases such as Moniliophthora roreri (monilia), Moniliophthora perniciosa (witch’s broom), and Phytophthora palmivora (black pod disease), applying manual strategies like removing and burying infected pods. Grafting also serves as a tool for tree renewal, allowing vigorous shoots to replace declining branches and extend the plant’s productive life.

These practices are grounded in observation and empirical experimentation, often supported by institutional programs such as the Federación Nacional de Cacaoteros, which classifies trees by performance (e.g., FL3—Federación Lebrija 3) [50]. Still, symbolic knowledge persists; farmers distinguish cacao varieties by flower color or pod shape and often compare them to dog breeds for their diversity and distinct behaviors. Such analogies underscore the depth of local expertise in maintaining genetic diversity and adapting to evolving environmental pressures.

4.4. Cultural Dimension

The cultural dimension refers to the memories, traditions, and forms of self-identification maintained and transformed by peasant communities [6]. These cultural traits manifest in daily life through inherited practices, especially those related to cacao cultivation, that are passed down across generations and continuously reshaped by environmental, economic, and relational dynamics. Rather than fixed traditions, these practices reflect a living memory that operates as a collective learning process: communities reinterpret past experiences in the present to assign them new meaning. This dynamic reinforces the heterogeneity of peasant life. Even within a single municipality such as Lebrija, there exist multiple and sometimes contrasting expressions of what it means to be a campesino, as illustrated in the self-perception map co-created with participants in Figure 5, where cacao farmers describe themselves not only through productive roles but also through affective, environmental, and generational lenses.

Figure 5.

Self-perception of cacao farmers. Note: This visual was developed from reflections shared by 50 cacao farmers during co-creation workshops. Each participant could contribute multiple statements during the collective exercises. The excerpts shown here are verbatim and were selected to illustrate the main themes that emerged from participants’ narratives.

At the heart of this dimension lies the idea of self-identification. Being a campesino is not only a material or occupational condition but also a symbolic one, rooted in daily experiences, responsibilities, and values. The knowledge systems built around cacao cultivation and environmental management, as explored in previous sections, are part of a continuous process of constructing local knowledge and adaptive practices, essential for resilience and sustainability in agroforestry systems [51,52]. In this section, we highlight three interrelated aspects of cultural identity among cacao-producing families in Lebrija: (1) self-perception and collective identity, (2) symbolic and practical uses of the cacao plant, and (3) agricultural logics associated with lunar cycles. These dimensions reveal how symbolic and ecological rationalities intertwine in everyday rural life, guiding both farming strategies and environmental care.

4.4.1. Self-Identification

Most families in Lebrija identify as “campesinos” or “campesinas”, but this identity is not monolithic. Some participants nuance or expand it with terms such as campesino–entrepreneur, cacao producer, or rural entrepreneur. For those who strongly adhere to the campesino label, the term evokes a way of life rooted in the land, being born and raised in the countryside, depending entirely on farming, and navigating persistent economic hardship. “Living in debt” is a recurring phrase in their narratives, highlighting how poverty is experienced not only as a financial condition but as a structural constraint. Far from being an outdated term, campesino remains a socially grounded and politically meaningful identity [7].

Others adopt hybrid identities, such as campesino–empresario, especially when they engage in value-added cacao production, such as making chocolate bars, bonbons, or cocoa powder. This shift is not seen as a rupture from tradition, but as an evolution within it. As one participant explained, “you don’t stop being a campesino because you sell your own chocolate.” These changes reflect the dynamics of what De Grammont describes as diversified agrarian societies, where rural livelihoods combine cultivation, transformation, and commercialization [7]. Similarly, some identify as entrepreneurs or productores agrícolas, placing greater emphasis on market integration and food security. In contrast, those who sell only dried beans often describe themselves simply as cacao producers, adopting a more productivism lens.

For some, education is part of their self-definition. They refer to themselves as campesino–lawyers or campesino–teachers, affirming that professional advancement does not cancel out rural belonging. Across all these variants, a common thread remains: being a cacao producer involves knowledge passed down through generations. This ancestral wisdom is increasingly complemented by technical training, often from initiatives like Misión Chocolate, but this hybridization is not without tension. Some participants expressed regret over replacing “criollo” cacao, prized for its high fat content and fine flavor, with more productive but less aromatic hybrids. “We sacrificed quality for quantity,” one farmer observed.

For many, cacao is more than a crop: it is a livelihood, a responsibility, and a legacy. Producing cacao means sustaining the family, creating jobs, and caring for the environment. Cacao’s compatibility with agroforestry systems reinforces its ecological value, particularly when grown under shade. However, even this practice is not straightforward. Trees like “cedro” or “nauno” may foster diseases like monilia, whereas species like abarco, whose small leaves allow dappled sunlight, are preferred. This level of discernment reflects a deep intertwining of ecological and cultural rationalities embedded in how farmers define who they are and how they cultivate.

4.4.2. Transformations and Uses of the Cacao Plant

For cacao-producing families in Lebrija, the cacao tree is more than a crop, it is a sacred presence, a “blessed tree” whose entire anatomy is considered useful. This deep reverence is reflected in an ethos where nothing goes to waste, blending ecological pragmatism with cultural continuity. As summarized in Table 1, each part of the cacao plant is repurposed in ways that reflect both traditional knowledge and local innovation.

Table 1.

“A blessed tree”: Uses of the cacao plant according to cacao-growing families in Lebrija.

Ancestral recipes, such as “chocolate de ojo”, which involves boiling a cow’s eye and adding chocolate, are still remembered by elders and praised for their supposed cognitive benefits. These practices evoke a living memory, where cacao is not just sustenance or income, but a cultural thread that ties generations together.

4.4.3. Lunar Practices and Agricultural Timing

The moon governs multiple facets of agricultural life. As noted by many participants (n = 45 of 50): “a campesino needs the moon for everything.” The sap of plants, they explain, follows lunar cycles, rising during the waxing and full phases, and descending during waning and new moons. This knowledge informs precise decisions on when to graft, prune, plant, fertilize, or apply pesticides. The diagram in Figure 6 illustrates the lunar rhythm that guides these tasks. For example, in Waning/New moons: Sap is down, then it is the best for pruning, fertilizing, sowing non-grafted cacao, or applying inputs to the lower plant. Similarly, in Waxing/Full moons: Sap is up, and therefore, is the best for grafting, planting root vegetables, or treating the upper plant. Or, during full or new moons, farmers traditionally stop all activity for three days to avoid the influence of luna brava, a phase deemed spiritually and physically unstable.

Figure 6.

Lunar cycle and agricultural timing in cacao cultivation. Note: This diagram represents how cacao producers in Lebrija associate moon phases with plant sap movement and crop interventions.

This agricultural logic is systematized in Table 2, which summarizes the timing of practices according to lunar phases. During either the full moon or new moon, families traditionally refrain from all agricultural activities for three days to avoid the effects of the luna brava, a phase believed to be physically and spiritually unstable. This pause embodies not only symbolic beliefs but also practices of care and prudence passed down through generations.

Table 2.

Lunar phases, sap dynamics, and recommended agricultural practices in cacao cultivation.

Successful grafting, in particular, is said to depend on symbolic practices such as abstaining from sexual intercourse the night before, based on the belief that “warm hands” can hinder the graft’s success. These practices reveal a holistic integration of cosmology, biology, and moral life.

While not all families follow lunar rules as strictly as “the old ones” did, often due to labor shortages or urgent needs, many still align their actions with lunar phases when possible. Some also prepare traditional remedies like “hiel de tinajo” (cow bile), dried under specific moon phases, later mixed with aguardiente and used to treat blood sugar issues or as a body cleanse. Embedded knowledge reflects how campesino families adapt symbolic systems to ecological rhythms, reinforcing a cultural logic of sustainability rooted in both memory and observation.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study provide a grounded understanding of how cacao-producing families in Lebrija articulate multidimensional strategies to navigate the tensions between tradition and modernity, environmental degradation and ecological care, and exclusion from markets and community-driven resilience. These families do not operate within isolated agricultural systems but as part of territorially rooted social fabrics shaped by memory, identity, and collective experimentation.

One of the central contributions of this research lies in revealing how campesino identity is not a fixed or monolithic condition but a lived process negotiated across generations, roles, and practices. As illustrated in the self-perception map and throughout the results, the term “campesino” coexists with hybrid expressions such as “campesino-entrepreneur,” “cacao producer,” or even “campesino-lawyer,” reflecting how rural subjects simultaneously inhabit traditional and modern rationalities. These identities are attached not only in productive roles but in symbolic, ecological, and pedagogical dimensions, such as lunar practices or the teaching of seed selection techniques, thus reinforcing the idea of campesino knowledge as a repertoire of situated competencies.

Territorial dynamics in Lebrija show how spatial organization, water governance, and infrastructure are not neutral or technical matters but fields of power and memory. The participatory cartographies revealed a profound awareness of spatial justice: communities recognize that legal borders do not always reflect lived territories, and that resource access, especially water, is unevenly distributed. Practices such as “sembrar el agua” or preserving forest patches express a localized environmental ethic rooted in both spirituality and empirical observation. These findings support arguments that rural sustainability must be read through emplaced forms of knowledge and governance [53,54,55,56].

From a productive standpoint, the agroecological matrix that emerges, centered on intercropping, seed selection, and symbolic cycles, challenges dominant models that prioritize monoculture, extractivism, or short-term yields. The “big box/small boxes” logic not only diversifies risk but affirms autonomy and food sovereignty. This mirrors agroecological principles present in other Latin American experiences [57], while introducing a culturally embedded form of risk management tied to lunar calendars, biological indicators, and moral–symbolic considerations. The nuanced preferences regarding shade trees, pruning techniques, and disease management show a technical rigor that is often overlooked in rural studies.

The organizational dimension reveals a fragile yet dynamic associative ecosystem. While formal associations face attrition due to youth migration and structural inequalities in value chains, informal networks, such as school-based assemblies, Don Floro’s shop, or El Manantial farm, act as critical nodes of coordination and mutual support. These examples echo broader findings on the importance of “invisible infrastructures” in sustaining rural economies, particularly where institutional support is limited [58,59,60].

At the cultural level, the transformation and full use of the cacao plant stands out not only for its material efficiency but for its symbolic depth. The idea of cacao as a “blessed tree” integrates food, medicine, ritual, and artisanal production, reinforcing what other authors have described as re-existence: a cultural-political practice that updates ancestral meaning through daily life [61,62,63]. This is especially evident in practices like wrapping children in freshly harvested cacao pods, crafting jewelry from aborted fruits, or preparing mucilage-based truffles, which demonstrate how technical knowledge and cultural creativity co-produce value.

Nonetheless, the study also reveals key vulnerabilities. The ecological degradation linked to poultry farms, water contamination, and urban expansion reflects a broader territorial injustice, where peasant communities bear the externalities of development without participating in its design. These asymmetries are compounded by structural barriers in commercialization, often forcing producers to sell low-value raw material while repurchasing transformed cacao at unaffordable prices. In this context, experiences like Misión Chocolate, despite their limitations, represent micro-scale innovations in local value chains that deserve greater institutional backing.

Finally, the intergenerational erosion of lunar-based agricultural logics raises concerns about the sustainability of symbolic knowledge systems. While some families continue to graft, plant, or prune based on lunar rhythms, younger generations face time constraints, labor shortages, and the increasing influence of market calendars. This loss is not merely cultural but strategic: the lunar calendar encapsulates complex ecological intelligence adapted to the rhythms of the local environment. Future initiatives must therefore support not only technical training but also the transmission of these symbolic frameworks.

Overall, the case of Lebrija illustrates how rural families actively construct sustainability from below, weaving together ancestral knowledge, ecological care, diversified production, and symbolic practices. These strategies offer critical alternatives to technocratic development paradigms and underscore the need for public policies that recognize and strengthen campesino epistemologies. Rather than treating peasant communities as recipients of innovation, this study affirms them as producers of knowledge, identity, and resilience in the face of multiple crises.

6. Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that cacao-producing families in Lebrija are not merely agricultural workers or beneficiaries of rural development policies, but protagonists in the co-creation of sustainable, culturally rooted territories. Their practices, ranging from water rituals to grafting techniques and lunar calendar, express a sophisticated integration of ecological knowledge, symbolic systems, and community organization. Rather than reproducing a nostalgic or romanticized image of rural life, these findings present a dynamic and adaptive campesino rationality that blends ancestral memory with strategic innovation.

At the heart of this system lies a fluid, plural conception of campesino identity. Families identify not only as producers, but as cultural guardians, rural entrepreneurs, knowledge holders, and stewards of biodiversity. This identity is embodied in the way they interpret plant behavior, repurpose every part of the cacao tree, and organize social life around shared infrastructure and informal networks. The production and transformation of cacao, particularly led by women, becomes both an economic and a cultural act, generating income, preserving memory, and reaffirming territorial belonging.

The study also reveals that traditional ecological knowledge is not static folklore, but an evolving body of empirical and symbolic wisdom capable of responding to environmental, social, and economic pressures. Practices such as intercropping, planting “according to the moon”, and “planting water” are not remnants of the past but contemporary strategies of sustainability grounded in local logic. These contrast sharply with dominant models of rural development that prioritize productivity over meaning, and uniformity over diversity.

However, these systems face critical threats. The erosion of associative work due to youth migration, the increasing environmental impacts of extractive activities, and the marginal position of smallholders in value chains all pose serious risks to the long-term viability of campesino strategies. While experiences such as Misión Chocolate point to the transformative potential of locally driven initiatives, their impact remains limited in the absence of institutional frameworks that truly value peasant knowledge and territorial intelligence.

The case of Lebrija thus contributes to broader discussions on sustainability in Latin America by shifting the focus from inputs and outputs to identity, memory, and ecological coherence. It calls for a paradigm shift: one in which public policy, academic research, and rural development converge around the recognition that sustainable futures are not built for rural communities, but with them, and, above all, from their own epistemologies. Listening to and supporting the knowledge systems of those who have long cultivated the land is not only a matter of justice, but of social and ecological necessity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.d.J.M.L. and P.A.P.G.; methodology, M.P.L.G. and P.A.P.G.; validation, E.J.P.C. and M.P.L.G.; formal analysis, M.P.L.G. and P.A.P.G.; investigation, M.P.L.G. and P.A.P.G.; data curation, D.B.M. and J.E.G.B.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B.M. and J.E.G.B.; writing—review and editing, D.B.M. and J.E.G.B.; visualization, E.J.P.C.; supervision, D.B.M. and J.E.G.B.; project administration, P.A.P.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Bioethics Committee of Universidad de Santander (protocol code Act No. 003, 27 February 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Leach, M.; Nisbett, N.; Cabral, L.; Harris, J.; Hossain, N.; Thompson, J. Food politics and development. World Dev. 2020, 134, 105024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Rios, L.A.; Vargas-Villegas, J.; Suarez, A. Local perceptions about rural abandonment drivers in the Colombian coffee region: Insights from the city of Manizales. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malapane, O.L.; Musakwa, W.; Chanza, N. Indigenous agricultural practices employed by the Vhavenda community in the Musina local municipality to promote sustainable environmental management. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.J.; Compain, G.; Kesteloot, T.; Meijer, M.; Muñoz, E.; Murtagh, S.; Saarinen, H.; van der Vaart, N. Fixing our food: Debunking 10 myths about the global food system and what drives hunger. Adv. Food Secur. Sustain. 2023, 8, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas. Resolution A/RES/73/165. Available online: https://docs.un.org/en/A/RES/73/165 (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia. Conceptualización del Campesinado en Colombia; Imprenta Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2020. Available online: http://www.icanh.gov.co (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- de Grammont, H.C. La nueva ruralidad en América Latina. Rev. Mex. Sociol. 2004, 66, 279–300. Available online: https://estudiosrurales.sdi.unam.mx/media/attachments/2024/06/03/la-nueva-ruralidad-en-america-latina.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- CEPAL-FAO. Agricultura Campesina en América Latina y el Caribe. Santiago de Chile 1986. Available online: https://www.nodal.am/2017/11/america-latina-la-region-mas-violenta-las-mujeres-al-menos-12-femicidios-diarios/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Ortiz Pérez, S. La Producción Campesina de un Espacio Cooperativo. Dinámicas Territoriales Hacia una Soberanía Alimentaria. 2014. Available online: http://rua.ua.es/dspace/handle/10045/41198 (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Gil, A.; Brennan, M.; Chaudhary, A.K.; Maximova, S.N. Evaluation of cacao projects in Colombia: The case of the rural Productive Partnerships Project (PAAP). Eval. Program Plan 2023, 97, 102230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintero, I.; Ceccaldi, A.; Martínez, H.; Santander, M.; Rodríguez, J.; Escobar, S. Dry cacao pulp in chocolate bars: A sustainable, nutrient-rich sweetener with enhanced sensory quality through refractance windows drying. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 100700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bystriakova, N.; Tovar, C.; Monro, A.; Moat, J.; Hendrigo, P.; Carretero, J.; Torres-Morales, G.; Diazgranados, M. Colombia’s bioregions as a source of useful plants. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Estrada, H.; Díaz-Castillo, F.; Franco-Ospina, L.; Mercado-Camargo, J.; Guzmán-Ledezma, J.; Medina, J.D.; Gaitán-Ibarra, R. Folk medicine in the northern coast of Colombia: An overview. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2011, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R. The origins and practice of participatory rural appraisal. World Dev. 1994, 22, 953–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiani, O. Desarrollo Rural Desde una Perspectiva Territorial; Rimisp-Centro Latinoamericano para el Desarrollo Rural: Santiago, Chile, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Juárez, G. Review of concept of local development from a territorial view. Rev. Lider 2013, 23, 9–28. Available online: https://ceder.ulagos.cl/lider/images/numeros/23/1.-LIDER%2023_Juarez_pp9_28.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Ingram, V.; Janssen, V.; Neh, V.A.; Pratihast, A.K. Cocoa driven deforestation in Cameroon: Practices and policy. Policy Econ 2025, 177, 103533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkor, P.; Siabi, E.K.; Frimpong, K.; Frimpong, P.T.; Mensah, S.K.; Vuu, C.; Siabi, E.S.; Nyantakyi, E.K.; Agariga, F.; Atta-Darkwa, T.; et al. Impacts of illegal Artisanal and small-scale gold mining on livelihoods in cocoa farming communities: A case of Amansie West District, Ghana. Resour. Policy 2024, 91, 104879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagunga, G.; Ayamga, M.; Laube, W.; Ansah, I.G.K.; Kornher, L.; Kotu, B.H. Agroecology and resilience of smallholder food security: A systematic review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1267630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robledo-Márquez, K.; Ramírez, V.; González-Córdova, A.; Ramírez-Rodríguez, Y.; García-Ortega, L.; Trujillo, J. Research opportunities: Traditional fermented beverages in Mexico. Cultural, microbiological, chemical, and functional aspects. Food Res. Int. 2021, 147, 110482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerding, S.G.; Trinh, B.H. A cross-cultural study: How product attributes and cultural values influence chocolate preferences. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 19, 101579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilombo, A.; Van Der Horst, D. Livelihoods and coping strategies of local communities on previous customary land in limbo of commercial agricultural development: Lessons from the farm block program in Zambia. Land Use Policy 2021, 104, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, L.N.; Shimelis, H. Production constraints and breeding approaches for cowpea improvement for drought prone agro-ecologies in Sub-Saharan Africa. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2020, 65, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibe, K.K.; Kollur, S.P. Livelihood and household clean cooking challenges in rural India: A community-based participatory approach for solutions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 119, 103846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Formación Permanente (INSFOP); Programa Especial para la Seguridad Alimentaria Nutricional Nacional (PESANN) Nicaragua; FAO. Diagnóstico Rural Participativo (DRP) y Planificación Comunitaria. 2008. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/b2102b42-0736-42c0-a996-753b9885e319/content (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Frans Geilfus. 80 Herramientas Para el Desarrollo Participativo, 8th ed.; Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture: San José, Costa Rica, 2009; Volume 1. Available online: http://www.iica.int (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Vasileiou, K.; Barnett, J.; Fraser, D.S. Integrating local and scientific knowledge in disaster risk reduction: A systematic review of motivations, processes, and outcomes. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 81, 103255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Lieres, J.S.; Sretha, A.; Kumar, M.N.; Velayudhan, N.K.; Devidas, A.R.; Ramesh, M.V. Promoting water-sustainability: A participatory co-design approach for addressing water-supply challenges in urban Kerala, Indi. J. Urban Manag. 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, R.; Stamm, C.; Staudacher, P. Participatory knowledge integration to promote safe pesticide use in Uganda. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 128, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezzo, X.; Belton, B.; Johnstone, G.; Callow, M. Myanmar’s fisheries in transition: Current status and opportunities for policy reform. Mar. Policy 2018, 97, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnworth, C.R.; Badstue, L.B.; de Groote, H.; Gitonga, Z. Do metal grain silos benefit women in Kenya, Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe? J. Stored Prod. Res. 2021, 93, 101734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antriyandarti, E.; Suprihatin, D.N.; Pangesti, A.W.; Samputra, P.L. The dual role of women in food security and agriculture in responding to climate change: Empirical evidence from Rural Java. Environ. Chall. 2024, 14, 100852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, H.V.; Sexsmith, K.; Matheu, M.; Gonzalez, A.R. Gendered adaptations to climate change in the Honduran coffee sector. Womens Stud. Int. Forum 2023, 98, 102720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, S.; Quercy, A.; Schleyer-Lindenmann, A. Territorial inertia versus adaptation to climate change. When local authorities discuss coastal management in a French Mediterranean region. Glob. Environ. Change 2023, 81, 102702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina-Usuga, L.; Parra-López, C.; Sánchez-Zamora, P.; Carmona-Torres, C. Towards socio-digital rural territories to drive digital transformation: General conceptualisation and application to the olive areas of Andalusia, Spain. Geoforum 2023, 145, 103827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar, A.M.; Valencia, L.F.; Villa, A.L. Life cycle assessment of Colombian cocoa pod husk transformation into value-added products. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2024, 25, 101772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maza-Villalobos, S.; Nicasio-Arzeta, S.; Benitez-Malvido, J.; Ramírez-Marcial, N.; Alvarado-Sosa, E.; Rincón-Arreola, D. Effect of land-use history on tree taxonomic and functional diversity in cocoa agroforestry plantations. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 367, 108952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, G.A.G.; Gutiérrez-Montes, I.; Núñez, H.E.H.; Salazar, J.C.S.; Casanoves, F. Relevance of local knowledge in decision-making and rural innovation: A methodological proposal for leveraging participation of Colombian cocoa producers. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 75, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gržinić, G.; Piotrowicz-Cieślak, A.; Klimkowicz-Pawlas, A.; Górny, R.L.; Ławniczek-Wałczyk, A.; Piechowicz, L.; Olkowska, E.; Potrykus, M.; Tankiewicz, M.; Krupka, M.; et al. Intensive poultry farming: A review of the impact on the environment and human health. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 160014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadi, H.; Keramati, P.; Taheri, F.; Rafiaani, P.; Teklemariam, D.; Gebrehiwot, K.; Hosseininia, G.; Van Passel, S.; Lebailly, P.; Witlox, F. Agricultural land conversion: Reviewing drought impacts and coping strategies. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 31, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D. Effects of urbanisation on the water balance—A long-term trajectory. Environ. Impact Assess Rev. 2009, 29, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.; Nuissl, H. Does urban sprawl drive changes in the water balance and policy?: The case of Leipzig (Germany) 1870–2003. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 80, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Li, X.; Nghiem, L.D.; Hatshan, M.R.; Lam, K.L.; Wang, Q. Assessing the effectiveness of site real-time adaptive control for stormwater quality control. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 56, 104324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emadodin, I.; Taravat, A.; Rajaei, M. Effects of urban sprawl on local climate: A case study, north central Iran. Urban Clim. 2016, 17, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, K.Y.; Palacios, M.R.; Gomez, C.A.M. Governance and policy limitations for sustainable urban land planning. The case of Mexico. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 259, 109575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Jin, G.; Tang, H.; Mo, Y.; Wang, Y.-G.; Li, L. Response of water quality to land use and sewage outfalls in different seasons. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 696, 134014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.; Anderson, C.; Williamson, R.; Dunning, K. Stakeholder perceptions of coastal environmental stressors in the Florida panhandle. Ocean. Coast Manag. 2024, 250, 107008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, A.J.; Dani, A.A. Institutional Pathways to Equity Addressing Inequality Traps; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, S. Family Farming in Latin America and the Caribbean: Looking for New Paths of Rural Development and Food Security; Working Paper No. 137; International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth (IPC-IG): Brasilia, Brazil, 2016; Available online: www.ipc-undp.organdsubscriptionscanberequestedbyemailtoipc@ipc-undp.org (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Zapata-Alvarez, A.; Bedoya-Vergara, C.; Porras-Barrientos, L.D.; Rojas-Mora, J.M.; Rodríguez-Cabal, H.A.; Gil-Garzon, M.A.; Martinez-Alvarez, O.L.; Ocampo-Arango, C.M.; Ardila-Castañeda, M.P.; Monsalve-F, Z.I. Molecular, biochemical, and sensorial characterization of cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) beans: A methodological pathway for the identification of new regional materials with outstanding profiles. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, A.S.; Peres, C.A.; Dodonov, P.; Mariano-Neto, E.; Faria, D.; Cassano, C.R. Mammals in cacao agroforests: Implications of management intensification in two contrasting landscapes. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 383, 109512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, V.B.; Pantoja, L.P.; Cavalcante Filho, E.H.; Haber, R.A.; Leandro-Silva, V.; Costa, D.L.P.; Alves Júnior, M.; Menezes Franco, T.M.; Machado Nery, M.K.; Lima Rua, M.; et al. Current bioclimatic suitability and climate change impacts on the risk of cacao moniliasis invasion in Pará. Ecol. Model. 2025, 505, 111106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonda, N.; Bori, P.J. Rural politics in undemocratic times: Exploring the emancipatory potential of small rural initiatives in authoritarian Hungary. Geoforum 2023, 143, 103766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledezma, J.F.M. Rediscovering rural territories: Local perceptions and the benefits of collective mapping for sustainable development in Colombian communities. Res. Glob. 2023, 7, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, V.H.; Law, W.W.; Williams, J.M. Advocacy coalitions in rural revitalisation: The roles of policy brokers and policy learning. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 136, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, A.; Wallet, F.; Huang, J. A collaborative and multidisciplinary approach to knowledge-based rural development: 25 years of the PSDR program in France. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 97, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfecto, I.; Vandermeer, J. The agroecological matrix as alternative to the land-sparing/agriculture intensification model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 5786–5791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.S.; Nguyen, T.D. Community assets and relative rurality index: A multi-dimensional measure of rurality. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 97, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Yao, B.; Wang, Y. A study on the relationship between high-quality development of the logistics industry and rural revitalization across different levels of industrial structure. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Kusadokoro, M.; Chitose, A. Financing road projects and its impact on off-farm work in rural China. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2025, 99, 102209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampeck, K.E. A constitutional approach to cacao money. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2021, 61, 101257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaue, L.M. 12th IFDC 2017 Special issue—Foods from Latin America and their nutritional contribution: A global perspective. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2019, 83, 103291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzaidi, A.; Amin, I.; Nawalyah, A.; Hamid, M.; Faizul, H. The effect of Malaysian cocoa extract on glucose levels and lipid profiles in diabetic rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 98, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).