1. Introduction

After the 1989 Revolution, the temporary emigration of Romanians for work became particularly widespread, as the change in political regime was accompanied by profound economic and social transformations. The restructuring of industry and the closure of unprofitable businesses were accompanied by the redundancy of a growing number of people who, lacking minimum subsistence possibilities, chose emigration as the only solution to the economic problems facing their families. In the post-revolutionary period, Italy became one of the most important destinations for Romanian emigration. This country is currently home to the largest Romanian diaspora in the world—approximately 1.08 million people on 1 January 2024, according to ISTAT data [

1]. Migration flows have increased over more than three decades, thanks to a tolerant attitude from the local population towards immigrants who were not directly competing for precarious and seasonal jobs. Also, regulatory laws passed in 1997, 2003, and 2006 played a crucial role, giving immigrants the possibility to obtain unlimited residence permits and the right to family reunification [

2].

In the absence of other alternatives in their country of origin and driven by the desire to succeed economically, the pioneers of Romanian emigration created migratory networks and niches around which solid Romanian communities coalesced [

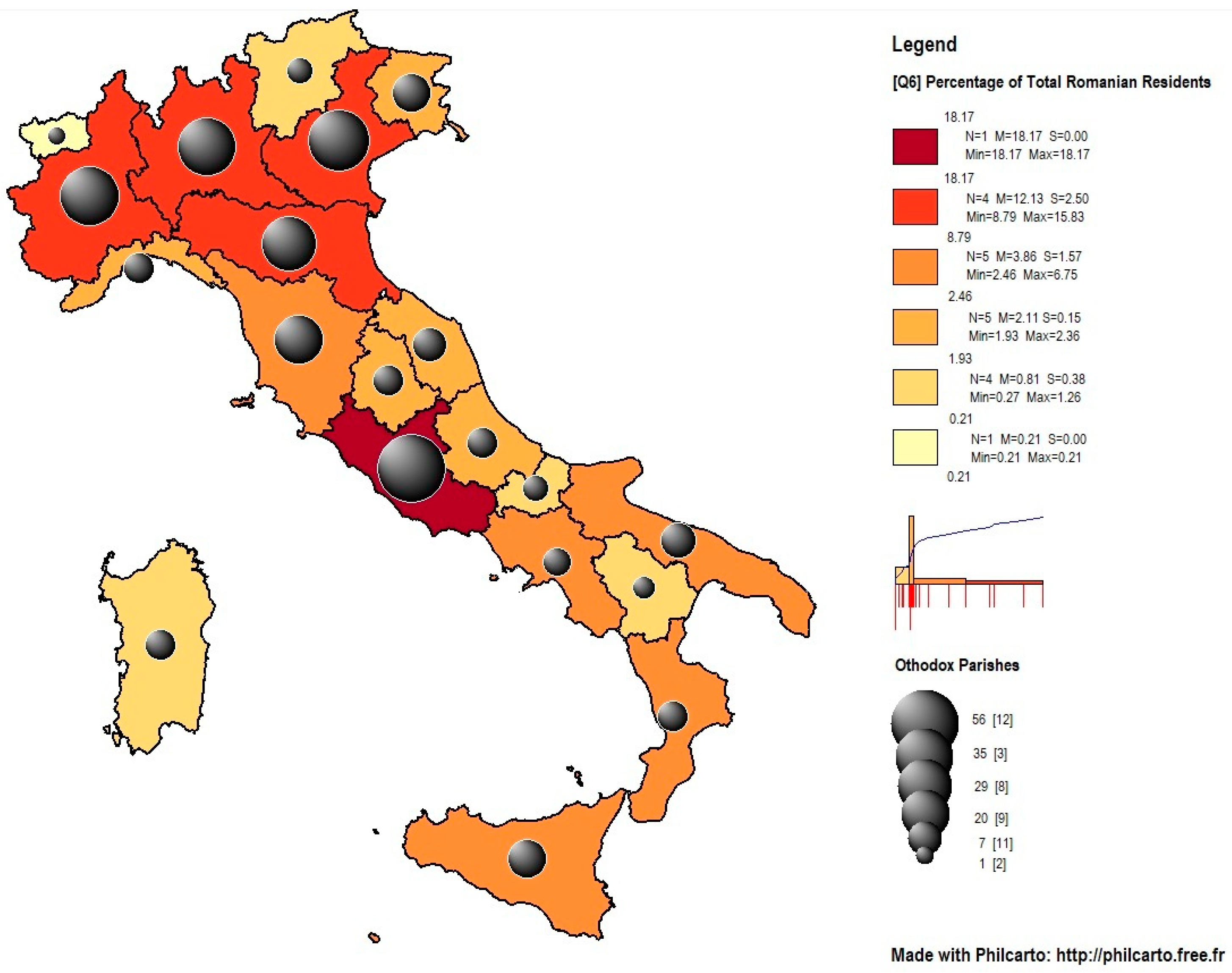

3]. The increasing size of Romanian emigration contributed to the emergence of a growing number of Orthodox parishes. Thus, the distribution of parishes in Italy generally follows the geographical distribution of Romanian communities, the most representative being those in Lazio, Lombardy, Piedmont, and Veneto (

Figure 1).

The beginnings of emigration were not easy. Many Romanian emigrants experienced feelings of being lost, marginalized, and even exploited. Bereft of family support, disoriented, and faced with the challenges of a foreign environment, they found solace in the Romanian Orthodox Church (ROC) and Romanian Orthodox communities. In a global context dominated by individualism and material values, religious identity has become an essential landmark for Romanian immigrants. In Italy, as in other countries with different religious traditions, Romanian immigrants have contributed to the formation of their own eparchies under the authority of the Romanian Orthodox Church [

4]. They place a strong emphasis on family and community values, which provides a sense of emotional stability for immigrants. In a situation where many Romanian immigrants are far from their families, the church becomes a place that promotes solidarity and mutual support, values that are essential for maintaining a sense of well-being. The role of the church in the context of immigration goes beyond the purely spiritual dimension, manifesting itself on several levels: identity, social, educational, and integrative. Orthodox parishes in Italy function as nodes in a “chain of memory” [

5], providing symbolic resources for maintaining links with cultural roots and building a positive self-identity in a foreign context. At the same time, they create opportunities for interaction between compatriots, strengthening support networks and facilitating the integration of immigrants into the labour market and Italian society [

6,

7].

Although the literature has extensively analyzed Romanian migration and its religious dimensions, studies on ROCs in the diaspora have generally focused on their role in preserving identity and on their spiritual dimension [

4,

8]. Less attention has been paid to a critical analysis of the multiple functions of the ROC, in particular its social, integrative, and transnational dimensions.

We chose to conduct interviews with Romanian priests in Italy because they provide access to information about the migrant community that is difficult to obtain through other methods. Beyond their role as advisors, mediators, and facilitators, priests are witnesses to realities that are less visible and more difficult to decipher, including personal, social, and cultural aspects that immigrants tend to avoid sharing. Our research has highlighted that parishes function not only as liturgical spaces but also as community centres and places for intergenerational socialization, supporting children and young people in maintaining their cultural roots and ethnic identity.

This study aims to investigate how the ROC in Italy contributes to reducing acculturation stress, supporting socio-cultural integration, and promoting the cultural heritage and identity of Romanian immigrants. In this context, the analysis refers to the “life cycle of ethnic churches” model proposed by Mullins [

9], which describes the evolution of migrant religious communities through three successive stages: support, consolidation, and adaptation/transformation. Applying this theoretical framework allows us to interpret how ROCs manage the maintenance of ethno-religious identity and social integration, providing a solid conceptual foundation for analyzing their multiple functions in the Romanian diaspora in Italy.

1.1. Religion, Migration, and Acculturation: A Literature Review

The scholarly concerns focusing on the interaction between religion and migration are vast and complex, addressing multiple dimensions of this complex relationship. Numerous authors have emphasized the central role of religion in the lives of migrants, both in terms of the process of adaptation in host societies and in the maintenance of ethnic and cultural identity [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Since the 1950s, pioneering research has emphasized the importance of religion in the lives of immigrants. Handlin [

19] and Herberg [

20] were among the first to analyze this issue in American society. Herberg argued that, although the first generations of immigrants tended to abandon their native language and some cultural traditions, religion was often preserved and used as a means of integration into the American triple melting pot of Protestants, Catholics, and Jews. Similarly, Hagan and Ebaugh [

6] (2003), analyzing the migratory experience of a transnational Mayan community, emphasized the multidimensional function of religion from the moment of the decision to migrate to integration in the host country and the maintenance of transnational ties. Drawing on empirical research, Portes and Rumbaut [

13] argue that religious practices are essential in processes of social exchange and in facilitating integration in multicultural societies.

The importance of places of worship as spaces of support and adaptation is a recurrent theme in the recent literature. Hirschman [

21] emphasizes their role as providers of essential elements for immigrants: refuge, resources, and respectability. Places of worship are perceived simultaneously as conservative institutions—preserving language, customs, and community solidarity—and as adaptive organizations, supporting the integration process and contributing to an increased quality of life [

9,

22]. Religion has been seen as a symbolic and institutional refuge for immigrants who have faced discrimination and social exclusion, while at the same time providing them with opportunities for economic mobility and recognition within the host society [

21]. In this sense, the founding of a church or temple has not only a spiritual function but also a social, community, and identity function. In analyzing the relationship between religion and migration, many authors have paid particular attention to processes of identity change. Cerulo [

23] argues that identities are fluid and multidimensional, shaped by historical and social contexts. Ajrouch [

24] emphasizes the overlapping and flexible nature of identities, and other authors [

11,

25] argue that religion often becomes a more salient identity marker in the diaspora than in the country of origin. Religion thus contributes to the consolidation of ethnic identity in migratory contexts. A relevant empirical example in this regard is the study by Maliepaard and Phalet [

26], who analyzed the relationship between religious identity expression and social integration among Dutch Muslims of Turkish and Moroccan origin. The results indicate stronger religious identification among minority groups, as opposed to majority groups, who show less support for visible religious practices. Compared to other religious denominations, the ROC takes a more conservative approach to worship practices and religious education, emphasizing the preservation of identity and the native language, which may influence how migrants integrate into the host society [

27]. Similarly, Guglielmi [

8] highlights that Romanian Orthodoxy in Italy differs from Italian Catholicism and Romanian Pentecostalism in its conservative religious practices, its integrative role in the community, and its emphasis on ethnic identity and language of origin.

A useful framework for analyzing religious communities in the diaspora is provided by Emmerich Arndt’s study [

28] on Turkish mosques in Germany. The author emphasizes the role of language as a fundamental tool in preserving cultural identity, facilitating social integration, and strengthening transnational ties. By examining how Turkish mosques manage the relationship between the mother tongue and the host country’s language in worship and community activities, the research highlights the delicate balance between preserving identity and adapting to the German environment, as well as the effects of these practices on younger generations.

The ROC in Italy functions as a transnational religious institution, capable of adapting to the social and cultural context of the host country without losing touch with the traditions and values of Romania. This adaptation manifests itself through a process of “religious glocalization” [

8], in which Orthodox traditions are reinterpreted according to local realities while maintaining community cohesion and the cultural identity of migrants. Ihlamur-Öner [

29] analyzes how the ROC in Italy has contributed to the construction of a “transnational Romanian-Italian Orthodox space.” The study highlights the institutional and organizational adaptations of the ROC, which respond to the spiritual and social needs of Romanian migrants and maintain links with Romania through parishes and various joint activities.

Mullins [

9] proposed the “ethnic church life-cycle model”—a sociological framework in which ethnic religious communities go through three distinct stages of development: the initial phase, the support phase, the community consolidation phase, and the adaptation or transformation phase. According to Mullins [

9], ethnic churches follow a three-stage development process. Initially, they provide religious and social support to migrants; subsequently, they consolidate institutionally, becoming community centres; finally, they enter a phase of adaptation, marking their gradual integration into the culture of the host society and the diminution of their initial identity role.

In the context of Romanian migration, Cormoș [

30] highlights how the Romanian Orthodox Church supports the preservation of ethnic identity, community cohesion, and the reduction in stress associated with cultural adaptation.

Acculturation is the process whereby individuals or groups adopt cultural elements from another culture as a result of direct and prolonged contact between two or more different cultures, with an emphasis on understanding the ways in which individuals change as a result of cultural contact [

31].

The concept of acculturation has been intensively studied over the years [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. Since the early 20th century, acculturation has become the concern of many American sociologists who have studied the lives of immigrant Americans of colour and how they have integrated into American society.

When immigrants have become detached from their culture of origin, they have felt insecure, disoriented, and even panic-stricken in unfamiliar territory. This state usually causes acculturation stress, a consequence of the tension and anxiety resulting from the person’s contact with a new culture and feelings of loneliness, confusion, and helplessness caused by the loss of familiar cultural cues and social rules [

42]. Acculturation can include changes in language, values, social norms, customs, lifestyles, and even identity. People going through the process of acculturation try to blend the culture of origin with that of the host country, which can cause both benefits and difficulties [

43].

1.2. Acculturation Stress and Adaptive Mechanisms Among Romanian Immigrants in Italy

Migration, a massive global phenomenon, brings with it not only economic benefits and opportunities but also profound social and psychological challenges. In Europe, and particularly in Italy, Romanian immigrant communities have expanded considerably in recent decades. Although many Romanians migrate in search of a better life, integration into a different cultural context entails a number of difficulties, which, over time, can lead to acculturation stress and significant emotional distress.

Acculturation stress, as conceptualized by Berry [

44], arises when the individual is confronted with tensions generated by cultural differences and the difficulty of responding simultaneously to the demands of the two cultures—the culture of origin and the society of destination. In the case of Romanian immigrants in Italy, this stress is aggravated by factors such as language barriers, discrimination, precarious social status, and the emotional break with the family left behind in Romania. Thus, many immigrants end up experiencing anxiety, depression, isolation, and low self-esteem, which can negatively affect the integration process and quality of life.

A central theoretical framework for understanding immigrant adaptation processes is the Cultural Stress Theory, formulated by Schwartz et al. [

45]. According to this theory, transitioning to a new socio-cultural context frequently generates specific forms of stress, different from everyday stress, caused by tension between the values and norms of the culture of origin and those of the host society. The consequences of this stress are reflected not only at the psychological level (anxiety, feelings of isolation) but also in the capacity for social and economic integration. In the case of Romanian immigrants in Italy, the church appears as a community actor that reduces cultural stress by providing symbolic and identity continuity through rituals, language, and traditions [

6,

7]. At the same time, the church facilitates integration by developing social networks and acting as an interface between the Romanian community and Italian society. Thus, the integration of the ROC from the perspective of Cultural Stress Theory emphasizes its dual dimension: preserving ethno-cultural identity and supporting integration processes in the host society.

A major impact factor in intensifying acculturation stress was the COVID-19 pandemic. During this period, many immigrants faced job loss, social isolation, and lack of adequate institutional support. Porumbescu [

46] highlighted, through a qualitative study based on interviews with 32 Romanian female care workers (caregivers), how the pandemic amplified their vulnerability. The women interviewed reported intense feelings of frustration, loneliness, and insecurity, exacerbated by their distance from their children and families in Romania and the lack of clear social support measures from the Italian state. These women were in a permanent inner conflict between the desire to return home and the need to continue working in order to support their families financially.

The phenomenon is not isolated. In another study, Jupîneanț Cioran et al. [

47] analyzed how Romanian migrant women in Spain experienced the lockdown period. According to the research, their homes became spaces fraught with tension and uncertainty amid social and economic restrictions and pressures. These women faced increased family responsibilities, severe financial hardship, and a heightened sense of isolation, which contributed to high levels of psychosocial stress. In this context of identity breakdown and instability, a sense of belonging becomes essential. Ahmed [

48] emphasizes the importance of reconnecting to a symbolic ‘home’ in order to alleviate feelings of cultural uprooting. The lack of an affective and cultural anchor can lead to alienation and the loss of a sense of continuity of identity. This is why the development of adaptive mechanisms—or coping strategies—is crucial for immigrants to regain their emotional equilibrium and integrate harmoniously into their new socio-cultural context.

1.3. Coping Strategies and Cultural Resilience

Coping, as theorized by Lazarus and Folkman [

49], is an active process of stress management involving constant interaction between the individual and the environment. It includes cognitive, emotional, and behavioural resources that can be mobilized to cope with difficulties. Among Romanian immigrants in Italy, these strategies vary according to personal and contextual factors, but some mechanisms prove to be particularly effective.

One of the most important resources is social support. Support networks—made up of family, friends, community members, or even religious groups—provide not only social but also emotional support. The study by Novara et al. [

50] demonstrated that informal social support is an important predictor of life satisfaction, sense of community belonging, and resilience. Thus, human connections are a fundamental pillar in the process of adaptation to a new culture.

At the same time, problem-focused coping strategies have proven to be beneficial. They involve a proactive and solution-oriented approach, which includes accepting the socio-cultural reality of the host country, learning the Italian language, developing new professional skills, and establishing social relations with locals. This active attitude not only contributes to more effective integration but also significantly reduces acculturation stress.

Resilience, understood as the ability to cope with adversity and return to psychological equilibrium, is another essential resource. According to the American Psychological Association (APA), resilience involves mental and emotional flexibility as well as the ability to turn negative experiences into opportunities for growth. The study by Verbena and colleagues [

51] shows that immigrant youth develop resilience through empathy, mutual support, and community involvement, which contributes to a stronger sense of belonging and long-term adjustment.

A distinctive element of the Romanian community in Italy is the role of the Romanian Orthodox Church. It functions not only as a place of worship but also as a meeting place and community cohesion. According to the research by Cozma and Giorda [

52], Orthodox churches in Italy contribute to the preservation of cultural and spiritual identity, providing emotional support and facilitating adaptation in a foreign context. In addition, Sonea [

53] emphasizes that the pastoral mission of the Romanian Church extends beyond religious boundaries, being actively involved in supporting migrants, both in the diaspora and upon.

2. Materials and Methods

This paper is based on the data obtained within scientific research that aimed to investigate the role of the Romanian Orthodox Church in Italy in alleviating the stress of acculturation, facilitating the socio-cultural integration of Romanian immigrants, and valorizing the Romanian cultural, traditional and identity heritage. The study has a qualitative character and was conducted in Italy, from April to May 2024, using semi-structured interviews as a research method. This technique allowed the collection of relevant data through a guided dialogue, providing valuable information in order to test the hypotheses formulated but also to rigorously describe the social phenomena involved [

54].

The research themes and hypotheses were defined prior to the start of the investigation, and the wording of the questions in the interviews was adaptive, allowing the content to be adjusted according to the profile and responses of each research participant. The instrument used was the interview guide, applied to a sample of ten Romanian Orthodox priests with a minimum of 5 years and a maximum of 22 years of pastoral experience in Italy, working in parishes in the following localities: Mestre (A.M., 54 years old; P.D.I., 29 years old), Mira (B.C., 48 years old), Portogruaro (B.I., 50 years old), Mirano (C.D.L., 48 years old), San Donà di Piave (C.F., 50 years old), Treviso (K.M., 53 years old), Noale (P.N., 58 years old), Cittadella–Padova (M.G., 35 years old), and Dolo (N.D., 37 years old).

The analysis of the interview was based on specific themes, formulated according to the structure of the interview, the purpose of the research, and the hypotheses mentioned. In regard to the context of the interview, we note that the interviewed priests were open in providing information and showing the evolution of the Church and the formation of Romanian communities in Romanian Orthodox churches in Italy.

In addition to the interview, the technique of direct observation was also used, especially in situations that involved direct interaction with the subjects under investigation, but also with the ecclesial environment and community spaces for Romanian immigrants and their families. The observation was participatory, with the researcher being actively involved in the context being analyzed, which allowed for an authentic perspective on the dynamics of social relations and the pastoral role of priests [

55]. Combining this technique with the semi-structured interview helped to increase the consistency and validity of the data obtained.

From a methodological perspective, the research approach fits into the exploratory paradigm, aiming to identify and analyze the perceptions expressed by the priests included in the sample. Given its limited size and inductive nature, we consider this investigation as a pilot study, which provides the conceptual and empirical premises necessary for the development of further research on a larger scale in order to deepen the thematic area.

The study conducted in Romanian parishes in Italy sought to answer some key questions about the role of the Romanian Orthodox Church in reducing acculturation stress, facilitating the socio-cultural integration of Romanian immigrants, and promoting Romanian cultural heritage, traditions, and identity:

- -

What are the problems related to migration and acculturation stress that Romanian immigrants bring to the attention of priests?

- -

How do the services, religious holidays, and cultural events organized by the ROC influence the process of preserving and strengthening the national and cultural identity of Romanians in Italy?

- -

How does the ROC get involved in developing social networks, both among members of the Romanian community and between Romanians and Italians?

- -

How does participating in religious services and parish activities help Romanians integrate into Italian society?

In order to capture the dimensions of this complex social phenomenon, with effects at the individual, family, and community levels, the following research hypotheses were formulated:

H1: The active involvement of Italian CSOs reduces the acculturation stress experienced by Romanian immigrants, providing them with emotional and practical support in the process of adapting to Italian society.

H2: Participation in services, cultural events, and traditions organized by the ROC has contributed significantly to maintaining the language, values, and ethnic identity of Romanian immigrants.

H3: Thanks to the support of the Romanian Orthodox Church, Romanians in Italy are well integrated, respect social norms, and benefit from strong community support networks.

3. Results

In order to highlight the results of the research, the purpose, the research hypotheses, and the pre-established themes were taken into account in order to analyze them: (T1: The Romanian Orthodox Church in Italy—a valuable resource in alleviating acculturation stress; T2: Romanian Orthodox Church in Italy—the basis for the formation of a new Romanian community; T3: Romanian Orthodox Church in Italy—an important role in preserving and valorizing the Romanian national identity).

T.1. Romanian Orthodox Church in Italy—a valuable resource in alleviating acculturation stress

From this research, it emerges that, in the first phase, the desire of the Church was to gather Romanians at the services throughout the year in order to preserve the faith and to strengthen the relationship with the divinity. Over time, it became clear that Romanians also needed guidance, support, and orientation in the new society, so the Church adapted to the needs of the immigrants, considering that the social should not replace the spiritual [

56].

“Because we hear their confessions, they open up to us with their problems, with their sorrows, we try to help them, a bond of soul is created between the priest and the faithful who come and strengthen their faith”

(N.D., 37 years old, 8 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

“Here, the priest must also get involved in such things to help those who are looking for a job or a place to live or looking for solutions to other problems”

(M.G., 35 years, pastoral experience in Italy).

The integration of Romanians can sometimes be difficult because they arrive in a new environment, with a new language, with different mentalities, behaviours, and values. Thus, the immigrant is forced to model his/her behaviour in accordance with the actions, requirements, norms, and values of the integrating collectivity [

57]. His or her integration implies knowledge of the language of the host country, access to the education system and labour market of that country, opportunities for professional development, equality before the law, cultural and religious freedom, and respect for the laws and traditions of the country in which he or she lives. But more often than not, Romanian immigrants encountered difficulties, as a result of which many of them asked for support or were directed to the Romanian Church, where each time, priests and other church representatives came to meet their needs. The church becomes part of civil society not only spiritually but also functionally [

58].

“It doesn’t matter whether you come to church or not. You are Romanian, we are all living the same drama, you need me, if God has enlightened you to come here, all the better, we come to your support.”

(K.M., 53 years old, 20 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

“Here, the priest must also get involved in such things to help those who are looking for a job or a place to live or have other problems and further recommend those Romanians.”

(P.D.I., 29 years old, 6 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

What has been observed in the present research and is important to emphasize is that the priest involves, in turn, other Romanian immigrants who can offer support at a given moment, becoming support persons for them. The priest calls for involvement and solidarity, which implies a willingness to provide pastoral support to people in need and division of labour [

59].

In this way, the priest creates and maintains a support network, at the level of the church community, for people or social groups in difficult situations [

60].

“They come to the church with all sorts of problems, from getting the paperwork, to finding a place to live, to finding a job. Strictly personal problems remain within the priest-believer relationship. But common problems are solved jointly. Here, in the church community, there are no more borders, we are all Romanians, this is Greater Romania. This is our joy: to all feel Romanian.”

(B.C., 48 years old, 5 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

The accounts of the priests interviewed highlight the fact that, in certain situations, the integration difficulties of immigrants exceed the intervention capacities of the parish and the community they represent, requiring additional support from other institutions or support structures. This is why they turn to and ask for the support of Catholic priests with whom they have developed a solid and trust-based relationship. When Roman Catholic priests understand the difficult problems faced by Romanian immigrants, they call on the relationships they have in the Italian community to be able to support them as much as possible. The communion between the Romanian Orthodox Church and the Italian Catholic Church is based on the religious principles of helping one’s fellow man and on “social work”, that in which one works together with other people for a social cause [

61]. At the same time, in the context of identifying the need for labour in the Italian community, Orthodox priests are often informed about these opportunities and pass them on to members of the Romanian community. This has facilitated the professional integration of a significant number of Romanian immigrants, contributing to their socio-economic stability.

“The Catholic priests knew the situation of their community and could recommend jobs for caregivers or babysitters for their children, etc. In addition to that, they knew the representatives of the companies and employers and asked the Romanian priest for people who could do the job. For example: ‘Father, I need a bricklayer, I need a mechanic, etc.’ Then at every Mass I would tell them what I had requested and in this way many Romanians found work”

(K.M., 53 years old, 20 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

“…the Church was the link between the Italian and Romanian communities for social integration and the labour market. And it was also a little reference from the priest of that community”

(B.I., 50 years old, 12 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

Orthodox priests also call on associations and institutions that can help Romanians. It is not enough for the church alone to be involved; it is important to have some institutional levers, and alongside the Romanian community, those in need or those who are going through difficult situations that they cannot manage on their own to be guided and supported. Pătuleanu [

58] points out that the church is not indifferent to the values and institutions of social life. On the contrary, it recognizes their importance and has a positive attitude towards them.

“Of course the priest can’t do it alone. Perhaps to the extent that he can call on other institutions, Roman Catholic priests, institutions that deal with charitable, social activities, etc. But the Romanian community around the church must necessarily be involved. A first aspect is that by involving the other Romanians in the community a much faster and more valid response and solution can be found. Another important aspect is that these Romanians have also been through similar situations. Romanians here started life in the gutter. And I know all their problems.”

(K.M., 53 years old, 20 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

The priests interviewed confirmed that there is no institution that deals specifically with Romanian immigrants and supports them in the problems they face. Therefore, they turn to various associations and institutions that have a social purpose, with limited power in solving the difficulties they face. Institutions can be an important factor in the migration process [

62], and as a result, the interviewed priests reinforce that it is necessary to have an institution that aims to support Romanian immigrants in their difficulties of integration and adaptation in the country of migration.

“The Church is in a way both mother and father for many Romanians. There is not even now any kind of Romanian social institution that has been for Romanians in Italy an open door to integration, to help and other things.”

(C.F., 50 years old, 11 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

“The NGOs and associations had their own, limited, very narrow aims, and neither the state institutions, nor the embassy, nor the consulate, were not present at all in the problems of Romanian emigrants, in situations that were often very dramatic, such as Romanians in prison, Romanians having to turn to a lawyer, if they found themselves in an unfair situation with the police or the carabinieri, etc. There were situations in which Romanians did not know where to turn to, situations that were hallucinating, revolting. They really didn’t know who to turn to and they came to the church. Then the priest looked for a lawyer or people who could help those in need.”

(C.D.L., 48, 12 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

The priests underline a situation of indifference of the Romanian state towards emigrants. They emphasize the importance of increased attention to Romanians in diaspora, as well as a deeper understanding of the needs and challenges they face and a collaboration between the church and the Romanian and Italian states for their support and guidance in difficult situations.

“If there was such an institution to deal with Romanians’ problems, people would not come to the priest or the church for solutions. And, not because Romanians would not go to the embassy or the consulate, but because they were left with unresolved problems and then they would come to the church.”

(C.D.L., 48 years old, 12 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

T.2. Romanian Orthodox Church in Italy—the basis for the formation of a new Romanian community

The Romanian Orthodox Church came to meet the needs of Romanian immigrants through social actions that valued the person and their rights, through its ability to get involved in the life of Romanian communities, thus strengthening Romanians’ trust in this institution.

“The Church has tried to be as open as possible to absolutely everything that means the soul, moral and spiritual needs of man”

(P.N., 58 years old, 12 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

The ROC facilitated the coagulation of Romanian communities also through actions aimed at integration and preservation of cultural identity. Once in Italy, Romanians underwent a process of assimilation and integration. They joined Romanian communities formed around Romanian churches for the preservation of values, traditions, and social relations. In this context, we bring to our attention the concept of collective consciousness proposed by Durkheim et al. [

63] to characterize the strong bond that exists between people. The collective consciousness, seen as a set of beliefs and feelings shared by the majority of members of the same society, is restrictive, imposing on the individual certain ways of thinking and behaving, which are materialized at the level of communities through social, moral, and religious rules [

64].

“In the diaspora, the church is the closest to Romanians who are away from home. And it can coagulate and tries to create a sense of community among us Romanians. The Church is the reality that is closest to the soul of a Romanian who is far away.”

(N.D., 37, 8 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

“Communities were organized around the church.”

(A.M., 54 years old, 22 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

The communities of Romanians organized around Romanian churches become a very important social and relational resource for immigrants, where they express their need to communicate and share their experiences. The need for socialization, which is at the origin of individuality and freedom of people, is thus identified, and in this process a sense of identity and the capacity for interdependent thinking and action are developed [

65].

“The Romanian is looking for a place to meet another Romanian, to talk to him, to tell his pain and, eventually, to look for a job through other Romanians who meet in church…”

(B.C., 48 years old, 5 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

“The Church is the only reality that is in direct contact with Romanians abroad, it is the one that feels the pulse and gives them the balance of a normal life.”

(N.D., 37 years old, 8 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

In Italy, the Orthodox Church has taken on a different connotation compared to the Church in Romania. It has adapted to the needs of Romanian immigrants and has accepted that their role is different from that at home. It has tried not to limit itself strictly to the liturgical life and has involved itself in cultural events, support, and promotion of the Romanian community.

“Bearing in mind that we are all in a foreign land, the church here takes on different connotations than in Romania, as a place where Romanians meet and pray.”

(M.G., 35 years old, 10 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

The Romanian community formed around the church becomes a second family. Communication is the basis of the relationships formed in the community, and solidarity helps them to come together as a social group, which gives them the strength and determination to continue their journey abroad in a safer and closer way. Social solidarity, a wholly moral phenomenon, is the glue that holds societies together, makes them function, and helps to maintain social order [

63].

“Through the activities organized by the church, the people in the community get to know each other, communicate and the church functions as one big family. It goes as a whole, forward.”

(M.G., 35 years old, 10 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

“Here, the faithful are more united than in the country and they are also closer to the priest. Those who come to church very often have a fairly close relationship. This is the mission of the church…”

(N.D., 37 years old, 8 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

Kinship relationships (marriage, baptisms) also contribute to the cohesion of Romanian communities. In a small entity, individuals are in direct contact with each other: they know each other’s biography, help each other, and participate in important events in the Romanian community. Kinship relationships emerge as essential ways of regulating group life and establishing a certain order, kinship being one of the important principles organizing human society.

“In these communities, Romanians are related to each other without previously knowing each other. Along the way, some are godfathers, others become godsons, some marry, that is to say, a family of their own is formed among certain members of the community. And in this way, the community binds even more.”

(N.D., 37 years old, 8 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

The Romanian community gives immigrants a sense of security of place, a sense of identity, a sense of social and relational landmark, a sense of being, and a sense of helping and communion. It is what gives them security of life in relation to their origin and identity.

T.3. Romanian Orthodox Church in Italy—important role in preserving and valorizing the Romanian national identity

These communities, formed around churches, initially had a religious character, but over time they also acquired a social character. The priest is directly involved in the formation of these communities, as he is the one who provides support and guidance to Romanian immigrants, both religiously and culturally. Modernity, however excessive and self-sufficient it may be, cannot replace identity. This is because the appeal to tradition and the need to legitimize ourselves are constants of the human spirit [

66].

“Romanians need not only the religious aspect, but also their culture because it is part of their identity…If you strip a man of his culture, you strip him of his identity. Therefore, the church should also maintain these aspects that are part of the Romanian’s identity…”

(K.M., 53 years old, 20 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

“It is important for every Romanian to live his social, traditional and spiritual identity with greater intensity. It is a necessity, otherwise life will not find its beauty.”

(B.I., 50 years old, 12 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

To preserve and promote Romanian traditions, it is important to organize traditional activities and events. Customs embody deep meanings about man’s relations with the surrounding world, with nature, about inter-human relations, about the normal course of social life, and about the solutions that, in an evolution often millenarian, mankind has found to make things return to normal when the order of the world was, for one reason or another, broken [

67].

“We have such events as: ‘Carols Festival’, ‘Days of the National Carriage’, ‘Eminescu Days’, ‘Romanian Language Days’, ‘Family Days’, all kinds of camps where cultural and traditional activities are organized.”

(N.D., 37 years old, 8 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

“When we organize the Church Feast, we also want to unite the community through what tradition means: folk costumes, each from its own area, music and folk dances from each area, music that is authentic, with historical, soul and cultural value. The church becomes a cultural centre, a house of culture.”

(P.D.I., 29 years old, 6 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

Romanian traditions are accompanied by a rich palette of cultural and moral values that are passed down from one generation to the next. These values are a guide for Romanians’ behaviour, contributing to interhuman connection. They promote community solidarity, honesty and integrity, and respect for the family, values which are important for the education and training of children and young people in the Romanian community. One can even speak of a common identity, which is more a matter of imaginary, contractual rationality, utility, and adherence to a certain type of social values [

68].

“We need to make a place for our children where we pass on both tradition and faith. If we are together, we will succeed! And if the children will see that we are a community, then they will understand what we Romanians are like”

(M.G., 35 years old, 10 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

“Cultural and moral values remain fundamental in Romanian communities abroad. Respect for family and traditions, solidarity, cultural and national identity are important values that help these communities to come together, to feel connected and to help each other in difficult times.”

(P.N., 58 years old, 12 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

The church is open and collaborates with various institutions and associations that are interested in Romanian traditions and their promotion.

“Our parish has collaborations with associations. For example, there is an Association called ‘Traian and Decebal’ that organizes shows, like the one on the feast of St Nicholas, and then there is the preparation of Christmas carols, all kinds of artists from the country come and there is a connection. Around 500 people participate… or on Romanian Language Day.”

(C.F., 50, 11 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

The Romanian Church emphasizes the promotion and preservation of cultural and national identity among children. Therefore, great emphasis is placed on carrying out traditional and cultural activities in which children are involved, speak Romanian, and socialize. From this point of view, immigrant children are simultaneously subjects of enculturation and acculturation. Thus, they are “enculturated” through learning the language, norms, and values of their parents’ culture of origin, but also “acculturated” through social interactions with other children, through the education system, and through the media in the country to which their parents immigrated [

69].

“The children, when they come to the summer school, at the beginning, they tend to speak only Italian, but we bring teachers from the country who don’t know a word of Italian and we do this on purpose, and then they have no way to speak Italian, and they have to speak Romanian.”

(N.D., 37 years old, 8 years of pastoral experience in Italy).

The Romanian Church is not only a spiritual institution but also a centre of Romanian culture and identity, a vital moral and social support for Romanian immigrants and their children, providing them with a sense of community and national belonging.

4. Discussion

Throughout more than three decades of emigration, the Romanian Orthodox Church has played an essential role in reducing the stress of acculturation felt by Romanian immigrants. This has been possible by cultivating relationships of empathy and emotional support within religious communities, which have become places of belonging and human warmth. The parishes provided spiritual counselling and helped immigrants to cope with the difficulties and challenges of adapting to a new society. In the 1990s, when Romanian immigration to Italy was often illegal, Romanian Orthodox parishes played an essential role in supporting their compatriots. In the absence of institutional structures accessible to immigrants, the Church became a place of refuge and community cohesion, developing social support mechanisms that could not be obtained through other channels [

52].

Romanians arriving in Italy faced language barriers, lack of residence or work permits, job insecurity, and inability to access social services [

70]. In this context, Romanian priests played not only a spiritual role but also a social, cultural, and administrative one. They became mediators and facilitators of the integration of Romanians into the host society. They provided practical and administrative support in obtaining residence permits and access to medical and educational services. Priests collaborated informally with local institutions and some Italian charitable organizations to solve the problems faced by Romanian immigrants. Thus, Romanian Orthodox parishes in Italy became pivotal institutions in the life of communities from the very first waves of migration.

Information obtained from interviews confirms studies in the field [

52], which reveal that the ROC in Italy has compensated for the absence of official integration structures by providing a framework of solidarity and mutual support, contributing both to survival in difficult conditions and to the consolidation of the collective identity of the Romanian diaspora. As the number of immigrants grew, Romanians began to consciously engage in the acculturation process, confirming the first hypothesis (

H1: The active involvement of Italian CSOs reduces the acculturation stress experienced by Romanian immigrants, providing them with emotional and practical support in the process of adapting to Italian society).

Gradually, their desire to assert and organize themselves as a community that wished to promote their cultural and national identity was increasingly evident [

70]. Their active participation in church life gave them access to a support network that facilitated their adaptation to the new sociocultural context. The results obtained by processing the interviews are confirmed by studies in the field [

71,

72,

73], according to which religious communities function as forms of social, economic, and emotional support, often also providing surrogate parental support for those separated from their families. For many Romanians who have emigrated individually, the ROC in Italy has been a symbolic family, a “second home”—a place where they could express their suffering, anxieties, and hopes. Attending services was also an opportunity to meet members of the community, which not only gave them a sense of belonging but also the chance to receive material assistance, such as food and clothing [

70]. The Romanian Orthodox Church has ensured the continuity of spiritual practices through services in Romanian, prayers, and family rituals, preserved traditions, and maintained living links with national roots, reducing the risk of cultural uprooting [

74]. Participation in national celebrations organized within the Church provided immigrants with access to cultural resources, which, in the new social context, contributed to the preservation of elements representative of their cultural and national identity [

75].

By organizing cultural events, meetings, language and traditions courses, the Church creates a united community and promotes a sense of belonging. In this way, the parish can be understood as a society in miniature, a meeting and cohesive space for all Romanian immigrants for whom religion represents either a mere cultural reference or a central element of their identity and existence [

76]. Orthodoxy becomes an element of the preservation of Romanian culture and spirituality, and the language, the binder of ethnic identity: ‘It is perhaps the only dimension of Romanianness that is not in doubt; culturally—Romanians have a rich popular culture, the basis of the constitution of our nation’ [

77].

The results obtained confirm the second hypothesis of the study (

H2: Participation in services, cultural events, and traditions organized by the ROC has contributed significantly to maintaining the language, values, and ethnic identity of Romanian immigrants). A comparative analysis with research dedicated to other religious communities proves essential for understanding linguistic and identity mechanisms. In this regard, Emmerich Arndt’s [

28] research on Turkish mosques in Germany provides a relevant framework for analyzing the role of language in maintaining ethnic identity. Both Turkish mosques and Romanian Orthodox churches in Italy use the mother tongue to transmit cultural and religious values. However, the major difference lies in the fact that Turkish mosques integrate German more actively into their educational programs and activities for young people, which facilitates social integration without severing ties with the Turkish language. In contrast, the Romanian Orthodox Church in Italy maintains a more conservative approach, keeping Romanian as the predominant language in services and activities, which helps to protect cultural identity but may slow down the process of adaptation to Italian society.

Analyzing the role of the Romanian Orthodox Church in Italy over more than three decades of migration, based on Mullins’ model of the “life cycle of ethnic churches,” [

9], we found a clear convergence with the first two phases described by the author: the support phase and the community consolidation phase. Thus, in the early years after the Revolution (1990–2000), we can speak of an initial stage, corresponding to the first phase described by Mullins, but with accents specific to the post-communist Romanian context. During this period, the ROC in Italy functioned as a veritable spiritual and community refuge for the first waves of Romanian immigrants, providing them with emotional support and practical assistance in the adaptation process (finding a job, administrative help, translations, and counselling to obtain the necessary documents). Subsequently, between 2000 and 2010, the ROC underwent a period of institutional consolidation, marked by an increase in the number of parishes, the establishment of the Metropolis, and the development of educational and cultural structures aimed at transmitting the Romanian language and traditions to new generations. With regard to the third stage of Mullins’ model [

9]—the adaptation or transformation phase—in which the church tends to integrate into the host society, our research reveals a distinctive feature of the ROC in Italy. Unlike some of the religious communities analyzed by Mullins, which underwent a gradual process of assimilation, the ROC in Italy tends toward a model of “stable diaspora,” in which ethno-religious identity is maintained over the long term. Thus, although there are openings towards the host society—collaborations with Italian parishes, joint social activities—the Romanian identity core remains dominant, with services being conducted almost exclusively in Romanian and national holidays and traditions occupying a central place in community life. The ROC in Italy confirms the logic of the Mullins model in the first two stages (which also confirms the first two hypotheses) but deviates from the hypothesis of eventual complete assimilation, given the specific nature of the Romanian diaspora. Therefore, the third hypothesis (

H3: Thanks to the support of the Romanian Orthodox Church, Romanians in Italy are well integrated, respect social norms, and benefit from strong community support networks) is only partially confirmed. The results we obtained indicate that religion functions simultaneously as a means of preserving national identity and as an instrument of partial social integration into Italian society. This hybrid position confirms that the “life cycle” of ethnic churches is not rigid but can undergo adaptations and particularizations depending on the historical, cultural, and religious context of the diaspora. Other studies on this topic confirm the results of our research [

8,

27]. The authors show that, compared to other denominations such as Italian Catholicism or Romanian Pentecostalism, the ROC adopts a more conservative approach to liturgical practices and religious education, supporting identity continuity and the preservation of the mother tongue, which can influence the process of integration of migrants into the host society.

Limits

This study is exploratory in nature and aims to investigate a phenomenon that has already been extensively researched but which brings new perspectives to the role of the Romanian Orthodox Church in Italy in the lives of Romanian immigrants.

From a methodological point of view, the research has certain limitations, as the interviews were conducted exclusively with Romanian priests from Orthodox parishes in Italy. The choice of this category is justified by the fact that priests, beyond their role as counsellors and mediators, are privileged witnesses to less visible realities that researchers can probe, analyze, and translate into scientific terms. These realities include personal, social, and cultural dimensions that immigrants would not normally share directly.

The absence of immigrants from the sample was determined both by their unavailability during the research period and by their reluctance to provide personal and family information related to their migration experience. To avoid ethical and confidentiality issues regarding data protection and informed consent, the analysis was limited to the testimonies of priests from ten Orthodox parishes.

Even though immigrants were not directly involved, we believe that the interviews with priests provide a clear and nuanced picture of the experiences of Romanian communities, thus partially compensating for this methodological limitation. In future research, we intend to conduct qualitative interviews with both Romanian immigrants and their employers in Italy, thus opening up new avenues for further exploration of the phenomenon.