Abstract

Remote work, as a technologically possible and widely applicable working mode, gained renewed attention during lockdowns amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. On one hand, remote work ensured that working remained sustainable; on the other hand, the unexpected and widespread nature of the immediate shift to remote work led to issues in terms of practicing and adapting to the process. Moreover, remote work can have strong social, economic, and environmental effects that have to be comprehensively understood. The high interest of employees in continuing with full or hybrid remote work calls for effective coping strategies at the individual and organizational levels in the future. This article focuses on academic studies documenting the peculiarities of remote work during the COVID-19 lockdowns. The aim is to identify the issues relating to remote work during the COVID-19 lockdowns that are documented in academic studies and thematically classify them into a range of factors. In this study, bibliometric and content analyses were employed, leading to comprehensive insights into the following areas: (1) remote work as a cause for changes in physical and psychological health; (2) remote work as a cause for changes in daily behavior, routine, and lifestyle; (3) factors that affect the process and productivity of remote work; (4) societal, economic, and environmental consequences of remote work; and (5) the distribution of the effects of remote work on individuals, economic subjects, and sectors. In conclusion, this study on working practices during the COVID-19 lockdowns that were documented in academic studies offers several benefits and areas of novelty: first, a comprehensive overview of the widespread process of adjusting to this new working mode; second, a classification of factors that affected the process at different stages and in different areas; and third, common factors that had more widespread effects during the remote working period. The findings also offer the following theoretical and practical implications: For researchers, this article can be a reference offering a holistic view of remote working during these lockdowns. For practitioners, it can provide an understanding of the impacting factors and their contextualization in terms of health, sociodemographic, and sectoral aspects can allow for more accurate human resource management strategies.

1. Introduction

Society successfully employed remote work before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, during this pandemic, this form of working gained additional meaning to ensure sustainable work, which, according to Eurofound [1], means staying in the workforce. At the same time, during the lockdowns caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, remote work acquired unusual characteristics: (1) it was widespread globally; (2) it was mostly forced due to the health emergency; (3) it was practiced in full, even by unexperienced individuals and organizations; (4) it challenged work–home boundaries and life–work balance; (5) its effects spread throughout society, the economy, and the environment due to changes in usual daily routines; and (6) there was no guidance for such a widespread practice based on previous experience. In this context, it can be seen that the issues of working practices amidst the COVID-19 lockdowns were related to the Sustainable Development Goals, such as SDG 3—“Good Health and Wellbeing”, SDG 5—“Gender Equality”, and SDG 8—“Decent Work and Economic Growth”.

As a result, during the pandemic, remote work gained renewed attention because of its unexpected and widespread nature and effects. In the long term, to reap the benefits of remote work in terms of factors such as improvement in living standards, territorial cohesion, and competitiveness [2], a transition to a full or hybrid form of remote work requires a management and preparation phase. These two phases were impossible to implement during the lockdowns. Moreover, the sudden change in working mode added additional pressure on performance quality at the individual and organizational levels. However, outcomes vary greatly depending on the particular case, requiring deep investigations of factors and reasons behind this.

Some decades ago, Green et al. [3] indicated that diverse forms of flexibility in work are a necessary response to changes in a market that creates opportunities for employees, especially women. Before the pandemic, scientists considered remote work a possible approach to improving work results but with some caution, in part considering such a mode an organizational innovation and perhaps rhetorical option [4]; attempts to discover benefits and possibly more effective ways to work remotely were still made, however. For example, Bae et al. [5] analyzed ways to increase employee engagement in remote work in the public sector through the assessment of leadership and management. A highly cited study [4] tried to collect impressions from public servants over several working days. Müller and Niessen [6] highlighted the role of self-leadership and self-goal setting in satisfaction with remote work. Billari et al. [7] concluded that broadband access encourages remote work, which allows highly educated women to combine career and family responsibilities. In a similar context, Kröll and Nüesch [8] concluded that flexibility in work and working from home increase job satisfaction. Simultaneously, remote work should maintain a similar effectiveness to on-site work. Effective implementation and management of remote work was already receiving attention decades ago [9]. Subsequently, scientists pointed out the importance of so-called telecommuting [10].

In general, before the pandemic, researchers tried to find answers to similar questions to those that arose during the lockdowns, when remote work was mandatory due to the health emergency, although the background for research and the understanding of capabilities changed noticeably. For example, some decades ago, Gillespie [11] pointed out that substituting travel with electronic communication is unrealistic. After two decades, the lockdowns demonstrated that a shift to full remote work [12], where applicable, is technologically possible and accepted by society (at least in a hybrid form), but appropriate management at the individual and organizational levels is required [12,13]. Amidst the lockdowns, in a policy brief, Marcus [14] debated the issues to which employers, workers, educators, trade unions, and governments will need to adapt because of the wider application of remote working in post-pandemic times. In this context, the peculiarities of widespread remote work in practice are important, and the experience of the lockdowns ensures knowledge that is based on large-scale, real-life experiments. Ropponen [15] noted that remote work, as a new normal phenomenon, requires further research.

After the pandemic, researchers tried to obtain a systematized understanding of the issue through literature analyses and by identifying research directions [16]. The present study goes further by expanding the time period for its analysis and paying attention to factors, effects, and consequences.

During the lockdowns, remote working was accompanied by challenges of both an organizational and emotional nature and led to achievements in terms of digitalization and employee wellbeing. The fast shift to fully remote work was complicated and included a wide spectrum of topics. The most pronounced issues that gained researchers’ attention related to work–home boundaries [17], gender disparities [18], health [19], stress [20], and many other factors, which are further analyzed within this research. However, the research on this issue is compartmentalized and does not provide a comprehensive understanding of remote work as a mass phenomenon. This is addressed within this research.

Within the academic literature, the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting lockdowns to ensure public health are characterized as driving forces for the development of remote working practices. Qu and Yan [21] indicate that the pandemic renewed discussions about the way we work, while Biagetti et al. [22] mention that the pandemic allowed for a massive remote working experiment. Hartig-Merkel [23] conclude that it led to accelerated digitalization. The OECD defines remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic as a mass experiment [2] and a forced experiment [24]. In general, remote work during the lockdowns was a strategy [22] not only for staying healthy but also for continuing economic activities and preserving wealth.

The modern economy’s technological development and societal lifestyle allow for partly or fully remote work depending on sectors’ and firms’ circumstances and their readiness levels. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the spread of this practice while at the same time leading to issues in terms of productivity and work–life balance. If widespread, a new form of working may deepen digital, gender, regional, urban–rural, social, and economic divides, as well as increase isolation and hidden overtime [24]. At the same time, remote work contributes to sustainability in many aspects—environmental, social, and economic (e.g., reduced greenhouse gas emissions, flexible working times, and lower costs). Additionally, when appropriately managed, remote work contributes to social inclusion and economic vitality in less developed territories [24]. To ensure success, transition processes and the creation of hybrid working environments require attention [2].

Work-from-anywhere models may vary significantly across communities, cultures, and sectors of economic activity. Moreover, some surveys discovered after the lockdowns that a high share of employees view remote work as a benefit for their mental health and would be happier if they could continue with this mode of working [25,26]. Successful adaptation calls for policy-making in both the business and public sectors, which is more effective when grounded on scientific findings. During lockdown, the academic community initiated active research on this process, actively searching for answers to the issues that arose during the lockdowns and better practices after the pandemic. Comprehensive and unexpected insights into fully remote work were presented within academic studies and may well guide future coping strategies at the individual and organizational levels.

The literature on remote work grew notably during the lockdowns. At an OECD conference, Marcolin [26] presented on two main focuses in the literature devoted to remote work during and post COVID-19: the prevalence and implications of remote work. Conclusions were drawn from an analysis of a non-exhaustive selection of papers and indicated issues such as preferences, future plans, productivity, and wellbeing. In this presentation, Marcolin [26] indicated that about 90% of workers and 60% of managers are highly interested in continuing with remote work in the future. Such a high level of interest calls for an in-depth understanding of the previously unmanaged experience to ensure resilient and effectively managed practices in the future.

This research develops this theme further and aims to identify which issues relating to remote work during the COVID-19 lockdowns have been documented in academic studies and thematically classify these into various factors. To achieve this aim, the author provides quantitative and qualitative analyses. In particular, a bibliometric analysis of keywords ensures an understanding of the most prominent themes and changes in focus areas over time, while a content analysis helps define the issues with remote work during the lockdowns and thematically classify them into different factors. The identified effects and consequences are then categorized as positive or negative.

The analysis results present focus areas that have been documented worldwide, specifically during the forced mass experiment of remote work. The findings offer a comprehensive understanding of practicing and adapting to remote work, which could be useful for future coping strategies and research on remote work. The focus areas are (1) remote work as a cause for changes in physical and psychological health; (2) remote work as a cause for changes in daily behavior, routine, and lifestyle; (3) factors that affect the process and productivity remote work; (4) societal, economic, and environmental consequences of remote work; and (5) the distribution of the effects of remote work on individuals, economic subjects, and sectors.

The article is presented in four sections. Section 2 explains the methods applied, data used, and limitations set for the present research in detail. Section 3 presents the research results based on an academic literature analysis—Section 3.1 offers a quantitative analysis, while Section 3.2 describes a qualitative analysis. In Section 4, the author summarizes the research findings and offers conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

As mentioned above, the aim of this study is to identify the issues relating to remote work during the COVID-19 lockdowns that were documented in academic studies and classify them thematically into different factors. To achieve this aim, the author employed bibliometric and content analyses of the data, which were selected from the Scopus database. As Mahna et al. [27] indicate, the combination of bibliometric analysis with content analysis ensures a rigorous multi-method technique that allows for in-depth understanding of the theme. An unexpected and widespread new working mode attracted immediate interest, which resulted in active publication of studies focused on features of practicing and adapting to this new working mode. Scopus is the research database with the widest coverage [28], ensuring sufficient and appropriate data within the selected theme. It is a common practice to use the Scopus database in research [27], as well as to base an analysis on one appropriate database [29].

The first part of this study was devoted to data selection and extraction. The criteria for the data search included keywords that reflect terms for a new mode of working and precisely determine the peculiarity of the pandemic period—lockdown, remote work, working from home, telecommuting, teleworking, and remote working. The search for these keywords was carried out using “Article title, Abstract, Keywords” in the Scopus database. The following limitations were set for the data extraction: language (English—as the international language of science), document form (journal article—as a more dynamic publication form compared with books and a more in-depth and highly cited publication form compared with conference papers), and publication date—from 2020 (beginning of the pandemic and following restrictions) till 14 February 2024 (final search in the Scopus database and starting point for the present study). The file with the data extracted from the Scopus database was saved in a Microsoft Excel format (.csv). After the search, the database offered 716 documents, which were checked for their relatedness with the selected thematic focus. After this evaluation, 629 documents were recognized as appropriate for the analysis.

As a result of the analysis, this article offers prominent research themes and thematically classified issues relating to remote work. This knowledge was acquired through two steps—first, a bibliometric analysis, particularly including the elaboration and analysis of the keyword co-occurrence network in the VOSviewer version 1.6.20. software [30], and second, a content analysis, involving the thematic extraction and classification of problems, solutions, trends, effects, and experiences. A summary of these research steps with explanations is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Research steps.

To conduct a bibliometric analysis, the following steps were taken (see a detailed summary in Table 1, Column 2): (a) definition of keywords that can characterize remote work during the lockdowns; (b) selection of database for searching based on the topic; (c) search using keywords in the selected database; (d) setting limitations for the research; (e) selection of appropriate documents; (f) export of file with dataset; (g) creation of a keyword co-occurrence map; (h) formation of clusters; (i) analysis of results. These steps provided an accurate analysis that allowed for an understanding of prevalent research themes in the field and changes in focus areas over time.

To conduct a content analysis, an following analytical framework was developed (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Analytical framework for content analysis within the article.

According to the above scheme, content analysis was applied to texts that investigated remote working practices during the lockdowns. Given the results of the bibliometric analysis, the author defined five thematic focuses for the content analysis. Within these thematic focuses, the author searched for terms that were used within the context of the related thematic blocks, as indicated above (Table 1 and Table 2). The reliability of the process was supported by the prior bibliometric analysis using VosViewer software. It can be seen that alongside with a quantitative analysis and clustering of keywords, the content analysis follows the same tendency in terms of themes.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Insights

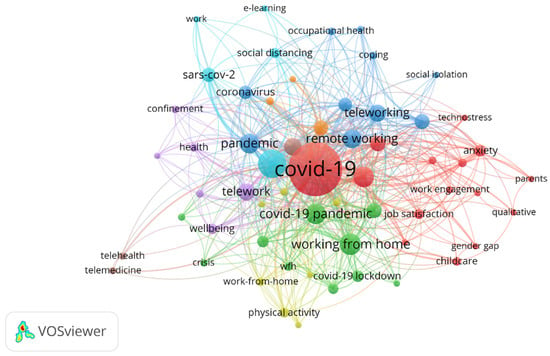

Keyword co-occurrence analysis allows for the identification of more frequent keywords within a theme (see Figure 1 and Table 3). Based on keywords, prominent research themes can be identified. Overall, 1815 keywords were observed within the selected articles. Unsurprisingly given the scope of the present research, keywords such as COVID-19 (331 occurrences), lockdown (91 occurrences), and pandemic (45 occurrences), which characterize this particular time, and keywords such as working from home (52 occurrences), remote work (49 occurrences), remote working (40 occurrences), and teleworking (34 occurrences), which characterize a new mode of working, appeared more frequently. If focus is put on particular features that characterized the COVID-19 lockdowns in terms of remote work, the ten top positions are held by the following keywords: mental health (36 occurrences); gender (27 occurrences); stress and wellbeing (26 occurrences each); productivity (16 occurrences); anxiety (15 occurrences); survey (12 occurrences); physical activity, job satisfaction, and social distancing (each 11 occurrences); depression, health, and childcare (each 9 occurrences); and work–family conflict, work–life balance, burnout, occupational health, resilience, confinement, workplace, and coping (7 occurrences each). The frequency of occurrences of keywords also demonstrates that the top three topics that raised concerns among researchers in relation to remote work during the COVID-19 lockdowns were mental health, gender issues, and wellbeing. From an economic point of view, it is surprising that the issue of productivity received less attention. However, the unexpected change in working mode caused serious mental and organizational pressures on individuals, which may explain the dominance of other issues over productivity.

Figure 1.

Co-occurrence of keywords in articles on remote work during lockdown. Note: The limitation to the occurrence of keywords is 5: 1815 keywords, 5 occurrences, 59 items (keywords), and 8 clusters. Source: Created by the author using data from the Scopus database and VOSviewer software.

Keyword co-occurrence analysis was performed in the VOSviewer software and resulted in eight clusters. Each cluster represents a thematic direction of research conducted on specific issues that appeared alongside with remote work. According to the keyword distribution across clusters, a list of prominent themes can be created.

The precise distribution of keywords across the eight clusters is presented in Table 3. These data allow us to understand the interconnectedness of the themes in this study.

Table 3.

Distribution of keywords across clusters.

Table 3.

Distribution of keywords across clusters.

| Cluster Number | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Cluster 1 (15 items) | Anxiety, childcare, COVID-19, depression, gender, gender gap, job satisfaction, parents, qualitative, remote work, sleep, teachers, techno-stress, work engagement, work–family conflict |

| Cluster 2 (10 items) | COVID-19 lockdown, COVID-19 pandemic, crisis, life satisfaction, productivity, public health, survey, wellbeing, wfh, working from home |

| Cluster 3 (10 items) | Coping, coping strategies, coronavirus, occupational health, pandemic, remote working, social isolation, stress, telecommuting, teleworking |

| Cluster 4 (7 items) | Burnout, employees, home office, physical activity, resilience, sedentary behavior, work-from-home |

| Cluster 5 (6 items) | Confinement, health, telework, wellbeing, working from home (wfh), workplace |

| Cluster 6 (5 items) | E-learning, lockdown, SARS-CoV-2, social distancing, work |

| Cluster 7 (3 items) | Gender roles, work from home, work–life balance |

| Cluster 8 (3 items) | Mental health, telehealth, telemedicine |

Created by the author using data from the Scopus database and VOSviewer software.

Cluster 1 includes keywords that represent family-related issues, psychological health, and the perception of remote work. Cluster 2 represents a thematic focus on personal and occupational wellbeing, as well as on surveys as the most appropriate method for collecting data on the peculiarities of remote work amidst lockdowns. Social isolation and coping strategies are the focus of Cluster 3, while Cluster 4 focuses on psychological and physical effects that appear as a result of remote work. Cluster 5 includes keywords relating to confinement, health, and wellbeing, which are strongly interlinked terms in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and remote work as a new working mode during lockdowns. The impact of social distancing on remote daily activities like learning and working is the focus of Cluster 6. Cluster 7 comprises discussions on work–life balance and gender roles while working from home. Finally, Cluster 8 represents research on how medical services were kept available in remote mode during lockdowns. Despite differences in thematic focuses, all clusters are interrelated, because they demonstrate reasons for and outcomes of remote work, while focusing on different areas of personal and professional life, as well as on the individual, organizational, and sectoral levels.

Cluster 1. Working at home challenged work–life balance and strongly affected familial relationships and daily routines. The theme of the blurred borders between home and work, as well as the active sharing of improvised working spaces at home, added pressure on work performance, home duties, and interpersonal relationships [17,31,32,33].

Cluster 2. Additional pressures that came alongside remote work significantly affected personal and occupational wellbeing for unexperienced and unprepared employees. Researchers actively collected opinions from employees on obstacles and benefits during their remote work [31,34,35,36,37]. Given differences in individual psychological readiness for remote work, different homes’ suitability for remote work, and occupational duties, experiences were both positive and negative.

Cluster 3. Widespread isolation provoked high stress levels and disruption of habitual activities. Strong effects from social isolation on individuals and organizations created a need for coping strategies that could help adjust to and overcome issues with remote work [35,38,39,40,41].

Cluster 4. Home offices affected employees both in psychological and physical terms [31,42,43,44,45,46]. In this context, the effects also differed depending on subjective factors such as perception and attitude, as well as objective factors such as the suitability of the home space for work, organizational support, and provision of technological aids.

Cluster 5. Remote work as a new working mode was initiated during confinement, with the aim of protecting public health. In this sense, restrictions and social isolation affected wellbeing [37,47,48,49]. Individual and organizational resilience and adaptability were particularly important for maintaining wellbeing.

Cluster 6. Social distancing was practiced for all activities, including learning and working, as a measure for ensuring public health. The consequent reduction in social contact showed up clearly in individuals’ and organizations’ performance and wellbeing [50,51,52].

Cluster 7. Simultaneous attention to work and home, as well as joint sharing of home working spaces, interfered with the perception and performance of remote employees. Gender roles were the main factor that was reconsidered in this new working mode, in both directions—both towards gender equity and widening the gender gap [18,53,54,55].

Cluster 8. Provision of health services amidst high infection risks and widespread social distancing was the most challenging task. The newest technological solutions ensured the possibility for patients and doctors to stay in contact [56,57,58]. This completely new approach challenged all stakeholders and encouraged healthcare digitalization.

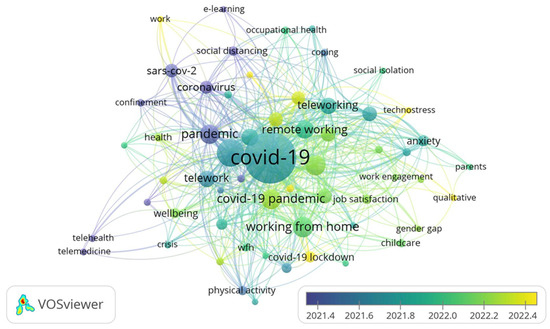

The figure below (Figure 2) presents an overlay of the keywords. This technique allows for the characterization of tendencies and changes in focus areas across urgent themes. Of course, all issues represented by keywords within this analysis remained topical during all lockdowns. At the same time, during the pandemic, the most troubling issues caused by unusual working conditions varied, which led to a change in and expansion of the thematic emphasis in research.

Figure 2.

Overlay visualization of keywords in articles on remote work during lockdown. Note: The limitation to the occurrence of keywords is 5: 1815 keywords, 5 occurrences, 59 items (keywords), and 8 clusters. Source: Created by the author using data from the Scopus database and VOSviewer software.

The social distancing and confinement that resulted in lockdowns were core features that ushered in completely new working mode in terms of prevalence. After social distancing and confinement became widespread, society experienced a reduction in physical activity and increase in anxiety, which gained immediate scientific attention. Researchers studied the process of remote work and its outcomes in terms of occupational health. Later, when remote working became more widespread, researchers delved into the peculiarities and difficulties of remote work caused by childcare, work engagement, techno-stress, the gender gap, and other significant factors.

In conclusion, the quantitative analysis described here presents a thematic focus that clearly represents concerns, obstacles, and outcomes in terms of remote work. The next step within the analysis, which is also a main focus of this research, is to distinguish and classify these issues. The author offers thematically classified issues related to remote work that impact (1) physical and psychological health; (2) daily routines; (3) the working process and productivity; (4) societal, economic, and environmental processes; and (5) economic subjects and sectors.

3.2. Qualitative Insights

During the COVID-19 pandemic, limitations that were implemented to protect the population’s health stimulated unexpected and widespread reconsideration of working practices (where applicable) and fostered digitalization of working processes. Hartig-Merkel [23] even highlights that the COVID-19 pandemic provided a push for faster digitalization. Besides the obvious technological benefits that accompanied this transition to a new mode of working, a comprehensive and detailed overview of the positive and negative consequences is required to improve future coping strategies at the individual and institutional levels.

This section presents and thematically classifies issues that appear due to remote work in terms of physical and psychological health (see Table 4), daily routines (see Table 5), the working process and its productivity (see Table 6), societal, economic, and environmental processes (see Table 7), and economic subjects and sectors (see Table 8).

Although the analysis results are based on studies from within a limited time frame (Materials and Methods Section), the instant reaction of the academic community during this time provides valuable and still relevant material for this analysis. Thematically classified issues expand and organize our knowledge on how remote work affected institutions, individuals, and work–life balance amidst an unusual economic situation.

Table 4.

Remote work as a cause for changes in physical and psychological health.

Table 4.

Remote work as a cause for changes in physical and psychological health.

| Factor | Examples of Themes and Terms Used Within the Context |

|---|---|

| Sleep Quality | Poor sleep quality; shorter sleeping time; earlier sleep and wake timings; sleep effect on immunity |

| Musculoskeletal Health | Musculoskeletal pain; sedentary time; long working hours; pain in neck, shoulders, hands, and wrists; a significant increase in pain intensity in the shoulder and elbow regions; physical load due to household chores |

| Changes in Weight | Weight gain; obesity; reduced physical activity; increased consumption of junk food; food industry advertising; decrease in weight |

| Cardiovascular Health | Cardiovascular risks; sedentary lifestyle; unhealthy diet pattern; psychological distress; smoking; alcohol misuse; cardiometabolic parameters |

| Headache/Migraine | Patients with chronic migraine; sleep-modifying factors; mental effects of working from home |

| Voice and Vocal Tract Health | Voice and vocal tract discomfort; telecommunication; dysphonia; voice training |

| Mental Health | Economic stress; parenting stress; augmented stress; anxiety; depression; changes in lifestyle; Yoga; cognitive and mental health; sleep disturbance; psychological vulnerability; suicide; obscured service burdens for women; men’s psychological wellbeing |

Compiled by the author based on Scopus data.

During the pandemic, health and related issues were the central focus of studies, as can be seen clearly across the clusters according to the network of keywords. In-detail analysis allows for an understanding of which changes in physical and psychological health appeared as a result of remote work.

Keightley, Duncan, and Gardner [19] conclude that work practices affect health-related behaviors and wellbeing, and that these effects may be detrimental. In turn, Delgado-Ortiz et al. [59] identify that populations did, indeed, experience changes in health-related behaviors. The analyzed data cover physical and psychological health, with more attention being paid to mental health disorders in individuals caused by the unexpected and forced change in working mode. In general, the observed effects on health allow us to conclude that changes in working mode increased stress and reduced physical activity, which destroyed habitual behaviors, worsened the ability to cope with individual daily routines, and led to sudden or chronic health issues. This situation was especially pressing due to the previously unexperienced overload on the healthcare systems [60].

Given the widespread nature of the pandemic and uncertainty relating to future working modes, researchers immediately contacted remote workers to receive feedback on any health issues that they experienced, using surveys as a reliable method for evaluation [61]. Many surveys were conducted covering particular health issues [62,63,64,65,66] or providing an overview [67,68].

Health issues that usually exhibit unfavorable trends globally [69,70,71,72] and which may have been significantly worsened during the COVID-19 lockdowns attracted researchers’ attention immediately. These health issues are sleep quality, obesity, cardiovascular health, and depression.

As far as individuals’ situations, their health conditions and the peculiarities of their remote work vary, and researchers found both negative and positive effects on health in remote employees. This findings allows for the conclusion that in a crisis situation, individuals need to manage stress and daily routines more than usual to turn harmful processes into gains. Keightley, Duncan, and Gardner [19] stress that organizational policies and support may encourage home working practices that are conducive to health.

The present analysis discovered a set of main health factors that received significant attention from the academic research community focusing on remote work. The author classifies them as follows: sleep quality, musculoskeletal health, changes in weight, cardiovascular health, headache or migraine, voice and vocal tract health, and mental health (see Table 3). These factors relate to both physical and psychological health. It is worth noting that the mentioned factors are interrelated and activated by remote work but have different effects depending on the specific case.

For example, sleep quality often worsened [73], but for some, it improved [62]. The effects differ depending on lifestyle, psychological health, demographic characteristics, occupational characteristics, and lockdown duration [66,74,75]. Importantly, the results do not vary in all cases. For example, females demonstrated higher rates of sleep disturbance in different contexts—in Bangladesh [66] and Italy [75]—as well as for depression, stress, and anxiety, which are predictive factors for sleep disturbance globally [73,75,76,77]. Serrão et al. [20] conclude that factors such as remote work, unemployment, and being unmarried exhibited higher effects on depression. Adaptation to forced and sudden remote work increased stress levels [20]. In this regard, Kahawage et al. [78] indicate that mood disorders caused by life events disrupt social rhythms.

Reduced physical activity turning into sedentary behavior is one of the more common features of remote work during lockdowns [61,67,79,80]. Long working hours with reduced physical activity led to musculoskeletal issues [63]. Studies reveal that unfavorable tendencies increased weight [81], cardiovascular risks [82], and musculoskeletal pain [67,83]. A dramatic reduction in physical activity and increases in screen time and food consumption even led to the introduction of a new term, “covibesity” [81], which drew attention to the possible prolonged negative effects of lockdowns on weight and cardiovascular health. Kenny [64] discovered a surprising health issue during remote work, concluding that active telecommunication may cause voice and vocal tract discomfort, thus demonstrating that despite mild and few symptoms, the wide spread of remote working would require additional attention to vocal wellness.

In conclusion, a systematized analysis of health issues enables the creation of a list of the most prevalent concerns that should be addressed through designing home working spaces, organizational policies, and self-management training for individuals. The issues discussed are both interconnected with each other and related to globally widespread health disorders. Given the technological possibilities and the fact that full or hybrid modes of remote working are already widely tested, appropriate health and human resource management policies, home interior designs, and work–life balance support are strongly required for healthier regular remote working in the future.

The next point that requires our attention relates to changes in behavior, daily routines, or even lifestyle. Forced changes in working mode led to modifications in usual schedules, which were characterized by clear work–home boundaries and the routines that are characteristic of modern society [32,84]. The unexpected transition to remote work with no or little previous experience challenged society’s ability to balance time and space for working and life activities. As has been shown, previous experience [41] and an appropriate situation at home [38,39,67,85] can ensure pleasant remote working. Some employees express readiness to work remotely even after the pandemic [25]. However, before that, employees needed to adjust their routines, practices, and even lifestyle. Those who were not able to successfully adjust their occupational duties were burdened with home duties or inappropriate working conditions and have opposite viewpoints, preferring on-site work, or at least a hybrid form of working [17,38,39,86].

The new working mode affected workers around the world significantly. The most challenging aspect was to maintain existing routines or successfully adjust them for this new working mode. The author classifies issues that seriously affected behavior, daily routine, and lifestyle into the following factors: food consumption, shopping, trips, unhealthy habits, sedentary lifestyle and screen time, working process at home, and behavioral issues (see Table 5). Table 5 presents the most common areas in which daily routines changed because of remote work. It is worth noting that these changes were both positive and negative.

Table 5.

Remote work as a cause for changes in daily behavior, routine, and lifestyle.

Table 5.

Remote work as a cause for changes in daily behavior, routine, and lifestyle.

| Factor | Examples of Themes and Terms Used Within the Context |

|---|---|

| Food Consumption | Increase in consumption of junk food, food shopping, food takeaway, and alcohol sales; changes in dietary behavior; improvements in consumption, purchasing, and engagement with food; decrease in fast-food and unhealthy snacks intakes; unlocking of culinary talents; experiments with new recipes. |

| Unhealthy Shopping Habits | Increased alcohol consumption; increased smoking; increase in online shopping; changes in shopping habits. |

| Trips | Higher number of shopping, personal business/social, and recreation trips; switch from public transport to private cars and bicycles; reductions in traveling time; alleviation of traffic congestion in developing countries; environmental benefits; expectations for decrease in car use for commuting after the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| Sedentary Lifestyle and Screen Time | E-communication, increased use of instant messaging, and video calls outside of normal working hours; increase in other forms of e-communications during leisure time; lack of face-to-face discussion and informal meetings; Yoga; increased sitting. |

| Working Process at Home | Increased workload; workplace safety and work schedules; physical load; fatigue; techno-fatigue; difficulties with managing work–life balance at home; challenged work–home boundaries; need for structure; need for autonomy; changes in lifestyle behaviors; maintenance of routines and attempts to establish new routines; audiovisual advertising; evaluation of job satisfaction. |

| Behavioral Issues | Increased intimate partner violence; increased abuse; increased risk of aggression in dogs; over-reaction; disruption of social and protective networks and decreased access to support services; enforced coexistence; economic stress. |

Compiled by the author based on Scopus data.

Food consumption, as a basic need, has undergone major changes, not only in terms of daily habits but also in terms of lifestyle, regarding which Ben Hassen and El Bilali [87] indicate that people re-evaluated their health and eating practices and started to cook meals at home more than before. Consumption of unhealthier food and snacks increased in some places [67] while decreasing in others [87], highlighting the diversity of individual preferences and eating cultures. Researchers note that unhealthy habits have increased. For example, Delgado-Ortiz et al. [59] report increases in smoking and alcohol consumption. The groups which increased their alcohol consumption met challenges in remote work and with providing home-schooling [43]. Given the lockdown constraints and people’s fear of infection, online shopping increased substantially [87]. In terms of goods, ref. [81] shows that food shopping, takeaway food, and alcohol sales increased, which confirms the previously mentioned trend of food consumption and unhealthy habits being significant parts of daily routines that were affected by remote work during lockdown. High food sales were stimulated by advertising. For example, ref. [81] found that food advertising was intensified, both in general and in particular for children.

Trips are another aspect that underwent significant changes during lockdown. Traveling restrictions practically stopped touristic and professional trips, and remote work reduced the necessity for commuting to a minimum. Cuts in trips provided positive health-related and environmental effects. For example, the time that was usually spent on commuting was reallocated to longer sleeping time [88]. Some studies highlight benefits to physical health of not commuting to work [46]. However, researchers found that during lockdown, commuting to work was replaced by commuting for shopping, social, personal, business, and other-purpose trips [65,89]. Changes were reported in the choice of transport as well. Shibayama et al. [90] stress that commuting trips with public transport were replaced with other kinds of transport due to the high infection risks in public spaces [90]. Less trips mean higher environmental gains. Such gains were investigated in research conducted by Fabiani et al. [91], which research demonstrates that remote work leads to sustainability and work satisfaction. Given the technological possibilities and practical gains of remote work, some researchers hypothesize that the number of commuting trips will decrease after the pandemic [92].

Cuts in commuting to work are associated with increases in screen time and sedentary behavior, which provides a basis for changes in lifestyle. Remote working, online education, and professional e-communication, combined with the usual daily use of devices for personal needs, caused increases in screen time [81,93], which resulted in a worsening of mental and physical health [94,95].

Boguszewski et al. [83] and the authors of [96] linked the dramatic decrease in physical activity with pain in locomotive organs. Ishibashi and Taniguchi [65] even expressed concerns that remote work may lead to chronic physical inactivity. However, some case studies discovered alignment with guidelines for the recommended amount of physical activities [59,97]. Overall, remote work changed habitual lifestyles, because previously physically active people became inactive [98]. Researchers highlighted the necessity of educational strategies that promote physical activity [79,96,99] and recommended Yoga as a tool for improving one’s physical and psychological health [100].

In light of the sudden changes in daily routines, Kahawage et al. [78] link mood disorders with a disruption of social rhythms. It is worth noting that behavioral changes differed between younger and older generations [101]. Psychological sensibility challenged the ability to adapt to a new working mode. According to Kumar, Alok, and Banerjee [48], technological factors and supervisory support improve wellbeing during remote work. In their research, Navas-Martín et al. [102] evaluated the extent to which individuals tended to maintain or change their routines in new circumstances. Their findings based on a case study demonstrated that changes in daily routines depended on sociodemographic factors and conditions of shared living [102]. Changes in working mode affected routines of physical activity, leisure time [98], and work–life balance [17,33]. Ahmetoglu, Brumby, and Cox [103] defined common issues that appeared among individuals during remote work—fatigue, overwork, difficulties with concentrating, attention span, and increased chaos. Phenomena such as techno-fatigue are particularly prominent in conditions of remote work [104]. Marzban et al. [105] point out that the concerns relating to remote work differ between employers and employees, showing that employers worried about productivity losses, maintaining the work culture, and workplace health and safety. In contrast, employees were more worried about social interactions, internet connectivity, and increased workloads [52,105]. Experiences varied significantly: While some studies reported difficulties maintaining boundaries between work and life [19], others indicated that “temporal flexibility and job autonomy enhance the work-life balance of employees” [106] (p. 327). As Di Fusco et al. [82] conclude, remote work can affect lifestyles significantly. Some perceived remote work as a new lifestyle, the keeping of which would be an advantage for health [46]. Others reported lifestyle alterations while working remotely during lockdown [95]. Individuals with long distances between their workplace and home, a highest standard of lifestyle [91], and a higher need for flexibility [91] associated remote work with positive experiences.

Researchers discovered that not only daily routines and lifestyles but also home safety and the quality of relationships were significantly affected because of pervasive changes in working mode. For example, Niederkrotenthaler et al. [107] highlight an increase in domestic violence, van Gelder et al. [108] analyze the lack of detection of domestic violence during lockdown, while Soron et al. [109] and Alderson et al. [110] raise concerns about the availability of mental health services for victims. Factors such as enforced coexistence, economic stress, and disruption of social and protective networks stimulated domestic violence [110]. One unusual tendency relates to possible aggression from dogs in relation to their owners. Sherwell et al. [111] conclude that prolonged working from home stimulated more aggressive behavior in dogs towards their owner, with the aim to protect their space. At the same time, Victor and Mayer [112] note that pets provide crucial emotional support for their owners during remote work.

In conclusion, widespread remote working will undoubtedly have long-term implications, not only because of technological benefits being tested in real life but also because of changes in behavior and adjustments of daily routines and lifestyles of employees, as well as changing human resource management strategies of employers. As academic studies have shown, experiences differ, but practical implementation should ensure the necessary skills and mental maturity for better coping strategies in the future at the individual and organizational levels. From the perspective of technological effects, the lockdowns and remote work stimulated enforcement of the internet market and digital marketing. From the perspective of health effects, employees were able to implement flexible schedules and work in alignment with circadian preferences. From an environmental perspective, reduced trips contributed to sustainability, while from a safety perspective, an increase in domestic violence attracted condemnation from society and initiated debates on preventive measures and support for victims.

From an economic point of view, working processes should be continuous and productive, even in remote mode. Maintaining an ergonomic environment for working at home is challenging, because previous experience is based on clearly set boundaries between work and life, and any experience of remote work before the pandemic is scarce. Additionally, maintaining productivity occupies the minds of employers [105], because lockdowns and changes in working mode were accompanied by increased stress levels [67] and decreased job satisfaction [113,114]. Studies discovered both negative and positive experiences. Given these academic research findings, the author classifies factors that affect the process and productivity of remote work as follows: availability and quality of working space, surrounding atmosphere, technology resources, human resource management, maintenance of work–life balance, job satisfaction while working remotely, circadian preferences, sense of community, remote work peculiarities/consequences/additional benefits, and future work spaces for remote working (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Factors that affect the process and productivity of remote work.

Table 6.

Factors that affect the process and productivity of remote work.

| Factor | Examples of Themes and Terms Used Within the Context |

|---|---|

| Availability and Quality of Working Space | Working environment at home; workplace comfort; poor, unsuitable working environment; inadequate telework spaces; residential built environment; separate space; ergonomic furniture; access to home office materials; lack of dedicated spaces to work; size of teleworking space; furniture; workspace being adapted for both individual and shared use; type and surface of dwellings. |

| Surrounding Atmosphere | Light; humidity; thermal comfort; air comfort; visual comfort; landscape views outside; odor; outdoor noise; indoor noise; well-sound-insulated environment; poor sound insulation at home; ideal soundscape; positive sounds; natural sounds; music; high sound pressure levels; urban background; more than one teleworker per household; presence of animals; acoustic factors; building factors; urban factors; situational factors; person-related factors. |

| Technology Resources | Open-source software; adequate ICT resources; network connectivity; internet connectivity; access to resources like software and hardware; poor digital resources; AI technologies and tools; cloud computing technology; secure office environment; data security risks; technical glitches; full-scale ransomware attacks; IT teams; business continuity. |

| Human Resource Management | Frustration from leadership and management; difficulty being an inspiring leader; challenge of motivating creativity; employee care and training; help for employees to alleviate stress during enforced remote work; profiles for employees—“Solitary”, “Affiliative”; empathetic approach to manage knowledge workers; remote work task support; boosting resilience among employees; healthier workplaces; difficulty with managing teams; funding availability. |

| Maintenance of Work–Life Balance | Blurred work–life boundaries; parents with increased homeschooling needs; married female workers who have infants and toddlers; household responsibilities; distraction by other household members; coping strategies; happiness; mindfulness training; gender disparities. |

| Job Satisfaction while Working Remotely | Lack of motivation and concentration; loss of focus; reduced mental health and wellbeing; remote work satisfaction; professional isolation and family interference; support for concentration; relaxation; motivation; feeling of being connected to surroundings and comforted by presence of others; limiting or enhancing of freedom of behavior; freedom of sound expression; lack of informal contact with colleagues; resilient individuals; socioeconomic characteristics; audiovisual advertising. |

| Circadian Preferences | Morning types; evening types; modern society’s early-morning routines; sleep times; sleep misalignment with biological needs; social schedules; flexible employment schedules. |

| Sense of Community | Disrupted contact with colleagues and reduced networking; isolation; confinement with family; feeling of being connected to surroundings and comforted by presence of others; chronic loneliness; transient loneliness; online wellbeing meeting; maladaptive social cognition. |

| Remote Work Peculiarities/Consequences | Workload; opportunity to work overtime; flexibility of working hours; autonomy; scheduling flexibility; task interdependence; burnout levels of mothers in leadership positions; cyberloafing as way to handle stress; information overload; increase in overall energy consumption; work–life balance; time for thinking about work-related problem-solving outside of work. |

| Future Work Spaces for Remote Working | Activity-based design of domestic environments; broader set of home uses and household compositions; healthier workplaces. |

Compiled by the author based on Scopus data.

During remote work, employees were responsible for organizing their workplace at home to be sufficiently ergonomic for continuous productive working. Fabiani et al. [91] point out that a comfortable room for work activities supports acceptance of remote work. In turn, acceptance means better job organization. Organization of appropriate workplaces was a significant challenge, especially in the case of remote workers who had children with remote schooling needs. In their research, Jaimes Torres et al. [115] indicate that space for remote work was established in spaces such as bedrooms, living rooms, and dining rooms. However, simply choosing a workspace was not enough. Remote workers needed a comfortable environment and appropriate technological equipment to maintain high-quality working processes. Several factors affect the comfort level of a working space and surrounding atmosphere, as shown by different case studies. For example, thermal comfort, noise insulation, and views outside [115], indoor soundscapes and the presence of others [38,39], the presence of pets [112], the availability of a separate space and ergonomic furniture [116], and visual comfort [85] are considered factors that affect the comfort level of working spaces. Of course, preferences and needs differ depending on individuals’ character, habits, and job duties.

A work–life balance that ensures sufficient comfort levels and respects one’s private space is highly subjective. Before the lockdowns, this balance was based on physically separated places—home and work. The new working mode confused employees due to the absence of such physical borders, which required a high level of discipline and mental readiness to manage daily routines and maintain appropriate levels of productivity and privacy. In the absence of clearly set boundaries between work and home life, a vast amount of remote workers did not have appropriate conditions for continuous and productive working. For example, women were less productive during remote work [54], which may be explained by their increased workload because of home duties [18,45].

Working from home was a new working mode for many. As Rania, Parisi, and Lagomarsino [117] emphasize, in theory, a meaningful organization of remote work could guarantee a better work–life balance. In practice, sudden changes in working mode directly affected job satisfaction, which had further effects on the quality of employees’ performance and their productivity. According to existing studies, job satisfaction suffered from the decline in workplace comfort [67], mental effects of remote work [67], techno-stress [44,118,119], professional isolation and family interference [113], information overload [120], social isolation and minimal possibility of social contacts [50], work–home conflict and overworking [119], and additional unpaid care work performed by women [121]. Positive effects on job satisfaction stemmed from temporal flexibility and job autonomy [106], successful integration of work and family identities into one’s idea of self [122], and not commuting to work [91]. According to Feng and Savani [54], women had lower job satisfaction than men during the lockdowns. Notably, audiovisual advertising tried to place emphasis on joint responsibility and equity between genders in remote work and other duties [55]. Nevertheless, studies revealed increased gender inequalities in household duties [18,123], with some positive exceptions [124].

For a clearer overview of attitudes to remote work, researchers divided workers into different profiles depending on their wellbeing and job performance [114], showing that levels of stress, feelings of loneliness, and creativity formed the basis for evaluation [114]. Such assessment is crucial for human resource management in usual circumstances, and even more so in unusual working conditions. In the new working mode, finding a balance between work and life was accompanied by actualization of traditional gender roles, cognitive overload, techno-stress, and intensive adjustments of daily routines and even lifestyle.

Besides the abovementioned factors in comfort level, stress level, and work–life balance, additional diversified features influenced job satisfaction—(1) the residential built environment [116]; (2) the availability of technological resources and work process organization [113]; (3) psychological profiles of employees [114]; (4) psychological wellbeing [106]; (5) the necessity of commuting [91]; (6) a sense of community [125]; (7) worker–parent identity integration [122]; (8) household duties [54]; (9) health-related quality of life [126]; and (10) circadian preferences [127]. For improvements in job satisfaction and hence in work productivity, individuals and organizations must be able to manage all these factors.

Remote working did provide certain level of autonomy and flexibility during the lockdowns [106]. In this context, researchers tested how being morning or evening person was linked with remote work performance, with the supposition that sleeping and working times may be aligned according to circadian preferences [127]. Crowley, Javadi, and Tamminen [84] concluded that the decreased impact of social schedules improved sleep-related health and allowed individuals to align their sleep and work times with their circadian preferences. However, they also found that despite an alignment with circadian preferences, other factors may decrease work engagement [84]. In turn, Staller and Randler [127] emphasized that morning types were more creative, while evening types were less creative during remote work. These implications are important for human resource management after the pandemic.

Amidst the confinement during lockdown, remote employees experienced opposite feelings—from strengthening of familial links [128] and benefits of virtual networking [46] to loneliness due to lack of social contacts [32,52] and wish to go back to office for meeting colleagues [105]. The younger generation increased virtual contacts with colleagues [101], while the lack of informal contacts with colleagues remained a concern for many [129]. Technological solutions have ensured networking between remote workers, while for those who still felt lonely during lockdowns, experts have offered mindfulness training [32]. In the context of familial relationships, researchers indicate such benefits as socialization of work [117], spending more time together [130], and stronger relationships [31].

Remote working did not only involve a stressful adaptation process but also positive possibilities to work in a more flexible [131,132] and autonomous environment that allows for better alignment with home duties, self-development, and biological rhythms [117]. However, in practice, not everyone was able to benefit from remote work. Burnout, stress, and overloads went along with remote work, especially for women and, particularly, mothers [47]. At the same time, female business owners highlighted gains from flexible and remote working [132]. In this regard, Adisa et al. [17] explain that mandatory remote work may reduce flexibility and provide negative experiences. From an organizational point of view, Reizer et al. [133] emphasize phenomena such as cyberloafing that are used by remote workers as tools to reduce the stress caused by fear of COVID-19. Remote workers experienced not only psychological stress but also increased expenses, e.g., increased energy consumption [115].

Depending on technological opportunities and employee interest, in the future, remote work may become more widespread than before the pandemic. The unexpected necessity to quickly adopt home spaces for remote work encouraged discussions on appropriate designs for remote work in the future. Boegheim et al. [134] suggest that the quality of an indoor environment affects employees at home and in office in a similar manner. Academic discussions relating to acoustic environments [38,39], healthy environments and sustainability [135], and updated requirements to new buildings and existing houses [136] have all been conducted. Frumkin [137] outlined how the pandemic encouraged professionals in different areas to consider future house designs and the surrounding environment, including innovative designs for reducing infection transmission, appropriate spaces for living and working, nature-based solutions, and innovative approaches to service delivery. Future home designs that are more comfortable for remote working would have to refer to sustainability, quality of life, a healthy environment, natural materials, transitional spaces, and folding furniture [135].

In conclusion, remote work, with its pervasive changes in daily routines, had consequences for society, the economy, and the environment. Given the widespread nature of remote work, its effects are both diverse on the one hand and exhibit clear common trends on the other. Researchers discovered both positive and negative consequences. The classification of data presented in Table 7 allows us to detect the most relevant concerns and achievements that can contribute to understanding how to cope with remote work in the future in a more effective way given particular societal, economic, and environmental issues.

Table 7.

Societal, economic, and environmental consequences of remote work.

Table 7.

Societal, economic, and environmental consequences of remote work.

| Factor | Examples of Themes and Terms Used Within the Context | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Consequences | Negative Consequences | |

| Natural world | Positive impact on the environment and CO2 emissions; Anthropause; decrease in footprint from transport emissions and energy consumption; positive impacts on air quality, water quality, noise level, waste generation, and wildlife. | Increased plastic consumption; increased amount of healthcare waste; increased levels of atmospheric ozone; elevated levels of illicit felling in forests and wildlife poaching. |

| Health | Quieter, less polluted environment; sleep improvements; positive self-rated mental health; re-evaluation of overall health practices; decreased symptoms of central hypersomnia; decreased symptoms of migraine; positive effects from parents’ remote working on children’s health; reduced forgetfulness compared with pre-lockdown. | Stress; depression; anxiety disorders; abnormal sleep; appetite changes; reduced libido; health anxiety; increased suicidality; sleep disturbance; reduced physical activity; weight gain; poor sleep quality; musculoskeletal pain; increased exposure to PM2.5. |

| Wellbeing | Psychological wellbeing; enjoyment from working from home; eliminated traveling time; decreased commuting time; improved daytime functioning; increased time for self-development and relaxation; more time for hobbies; more time for self-care; more time spent with friends; more time spent with family; concentration; motivation; freedom of sound expression; teleworking in public sector; lower level of fear compared with people going to workplace. | Overworking; fatigue; decline in workplace comfort; reduction in job satisfaction; digital detox; cognitive overload; lack of personal contact; monotonous daily routines; lowered mental wellbeing; lower social rhythmicity; inequality in habitability; differences between urban and rural areas; differences between families with or without children. |

| Family | Spending more time with family; positive effects on relationship with children; more quality time and stronger relationships with family; feeling of being connected to surroundings and comforted by presence of others; gratitude, closeness, and better quality of coparent interactions; renegotiation of traditional divisions of labor within couples during lockdown. | Gendered division of labor; gender imbalance; marital tension; unequal sharing of childcare duties; parenting; marital harmony worsening; increased domestic duties; blurred lines between home and work; outsourcing of housework; reduced housework help (familial support) from parents; domestic violence and abuse; psychological abuse; lack of smart working culture; lack of knowledge about mental health services during lockdown. |

| Economy | Increase in productivity; minimized cost of traveling; cost and time-savings for employers; household income; lowered likelihood of security misconduct; opportunities for disabled people to work; improvements towards gender equity in labor market; improvements in gender equity in terms of wages and working hours. | Reduction in workers’ efficiency; productivity losses; lower job productivity amongst women; lower job satisfaction amongst women; wage inequality; wage losses; more unpaid work amongst women; clear negative effects on highly valued jobs; drop in earnings for self-employed; risks of detaching women from professional work; unemployment; uncertainty in international trade and world economy. |

| Technologies | Application of new digital solutions in practice; rapid and widespread digitalization process; virtual communication and collaboration; telehealth. | Increased stress and anxiety due to prolonged time facing screens, tablets, and smart devices; poor internet connectivity; techno-stress; techno-invasion and techno-overload; techno-fatigue. |

| Scheduling | Less time spent getting ready for work and commuting; organizational trust and managerial trust in employees; changes in workforce management; temporal flexibility and job autonomy; split teams and social distancing for keeping workers healthy; high level of trust and value amongst organizations and workers; being supported within the team; sparks of creativity. | Chaotic work; loss of focus; overworking; tiredness; reduced face-to-face interactions; long workdays; lack of meaningful caregiving from organizations; insufficient separation of work and home; teleworking capacity. |

| Behavior | Substantial increase in online shopping; decrease in fast-food and unhealthy snack intake; more cooking of meals and experimenting with new recipes; reallocation of time usually spent commuting toward longer sleep time; more time for hobbies; more time for family; freer napping schedule; future housing design. | Increased alcohol consumption; increased consumption of junk food and processed food; reduction in perceived ability to be flexible; division of domestic work based on gender roles. |

Compiled by the author based on Scopus data.

The widespread introduction of lockdowns and dramatic reduction in traveling for any purpose improved people’s footprints in terms of transportation and energy consumption [138,139]. Banned or slowed economic and social activities had positive impacts on air quality, water quality, noise level, waste generation, and wildlife, as documented in the study by Chowdhury et al. [140]. At the same time, negative environmental impacts did not disappear. For example, [141] reported increased plastic consumption, while ref. [140] reported on increased healthcare waste and illicit activities against forests and wildlife.

Similarly, in the healthcare sector, remote work provided both positive and negative effects. Generally, the analyzed studies allow us to understand both the improvements and deterioration of physical and psychological health depending on the case under examination. For example, sleep quality was the most discussed issue. Ara et al. [66], Salfi et al. [75], and Zeduri et al. [77] found that age, gender, occupational position, and changes in work load were influencing factors for changed sleep quality during the lockdowns. Another issue was psychological health. Being a woman [53,142,143,144], stronger lockdown measures [142], and intensive mass media information on COVID-19 [68] were mentioned as causes for lower psychological wellbeing during remote working. Overall, fear for one’s health and unusual working modes appeared to have negative impacts; in turn, flexibility in work and reconsideration of healthcare practices appeared to have positive impacts. The most important thing is to overcome negative effects and not allow them to create unhealthy habits and worsen chronical health conditions; on the contrary, healthy habits have to be maintained in the long term.

Based on the existing studies on remote work during lockdown, wellbeing appears as one of the most discussed factors. Wellbeing amidst lockdowns mostly depended on the surrounding atmosphere at home, the specific conditions of private life, and individual abilities to adjust quickly to changes in working mode. Given the high diversity of individual characteristics, professional duties, and housing features, researchers understand wellbeing during remote work as a subjective phenomenon [49]. Case studies demonstrate both positive and negative outcomes: Positive effects were more likely experienced in cases with appropriate home workplace comfort, supported by ergonomics and technological equipment [38,39,117,131], as well as a possibility to spend more time with family [88,130] and on hobbies [88] and self-development [52,145], decreased commuting time [31,46,52], and improved daytime functioning [88,146]. Negative effects were more likely experienced in cases of worsened comfort in the workplace and surrounding environment [67,85,91,116], digital and cognitive overload [147,148], rising inequalities in terms of gender roles [18,45,53,148], inadequate housing quality to be appropriate for remote work [38,39,46,136,149], and availability of digital tools [120,150]. According to the existing studies, characteristics such as children in the household [151,152] and an urban living place [151] created a background for inequalities. Additionally, the unsafety of public spaces due to high infection risks stimulated inequalities in terms of habitability according to Jaimes Torres et al. [115]. In turn, increased domestic violence [107] worsened safety in private spaces.

Mohanan and Rajarathinam [150] accurately emphasize the particular role of work and family in people’s lives. Remote work with its major effect on work–life balance significantly influenced the wellbeing of families worldwide. The effects varied from a productive and pleasant time combining work duties with a strengthening of familial relationships to stress because of interference by family members, worsening relationships, a lack of professional face-to-face contacts, and an uncomfortable space for working. Improvements in the quantity and quality of time spent with family were valuable and positive outcomes [31,88,128,151,153,154,155]. Seiz [124] even concluded that lockdown measures and remote work encouraged a renegotiation of the traditional division of labor within couples. At the same time, traditional gender roles for women were actualized during lockdowns, which in turn stimulated gender inequalities. Martini, Mebane, and Greco [156] consider smart working culture a possible tool for solving gender inequalities and improving wellbeing through a better work–life balance. Beigi et al. [128] offer outsourcing as a strategy for how families could adjust to remote work in conditions of insufficient resources, especially in households with children. Those who experienced remote work’s negative outcomes on family life most strongly suffered from increased domestic work and care duties [77,157,158], domestic violence [107,109], increased gender inequalities [156,157,158], and blurred lines between home and work [17,31,33].

In a sense, the widespread remote work experiment is an economic phenomenon that demonstrates how effectively the economy and labor market are able join the digitalization trend. Based on the considered studies, the economic effects of remote work were spreading on the individual and collective levels, i.e., on households and entire sectors, as well as national economies. In particular, in terms of productivity and inequalities, the economic effects of remote work vary significantly from case to case. Differences in outcomes were caused by affecting factors such as flexibility of working time [33,131], which positively affected productivity and enabled parents to meet increasing homeschooling needs [159], which, in turn, affected productivity negatively. This analysis allows us to summarize the factors which affected productivity during remote work as follows: work flexibility [33], comfort of the working place [116], indoor environment and, particularly, visual comfort [85], remote work policies [160], gender differences [54]), information overload [120], and homeschooling needs [159]. The summary of academic findings revealed that productivity was increased [31,33,92,161] but at the same time accompanied by concerns over productivity losses [105,131]. The same is true for inequalities. Some studies concluded that gender [18,53,123], wage [162,163,164], and work inequalities [165] increased, while others discovered positive examples of improved gender equity [55,124,156,166], chances to diminish wage disparities [158], and expanded work possibilities [161].

Despite some negative effects from remote work, Escudero-Castillo, Mato-Díaz, and Rodríguez-Alvarez [167] emphasize that unemployment, not remote work of furloughs, was the main factor causing negative impacts. Given the widespread remote working during the lockdowns, existing technological possibilities, as well as employees’ interest in working in this way in the future, managers should adjust organizational structures and processes to digital economy needs, which is “a once-in-a-generation challenge” according to Bryant [168].

From a technological perspective, widespread remote work caused by lockdowns stimulated two main tendencies—digitalization and changes in the wellbeing and health of employees. In terms of digitalization, Hartig-Merkel [23] compares lockdown with a necessary push to intensify this process. Additionally, Hartig-Merkel [23] stresses the amplified benefits for both individuals and organizations. However, the promising path of rapid digitalization remained in the shadow of challenges in the form of home office arrangements and the mental wellbeing of unexperienced employees. Therefore, little attention has been paid to the digitalization process and the effects because of remote work during lockdown within the literature analyzed in this study. This is quite logical, because a sudden change in working mode caused high stress levels. In turn, digitalization outcomes need time to be fully understood and evaluated. The most discussed themes related to how individuals and organizations adjusted to virtual communication and collaboration [32,132,141,169], practiced telehealth [56,57,58], and introduced new technological solutions into their activities [34,170]. Renu [170] emphasizes that lockdowns stimulated new forms of interaction between governments, business, and society, as well as technological advancements which, besides remote work, included increased online shopping, robotic delivery systems, contactless payment systems, distance learning, telehealth, 3D printing, and online entertainment. Significant attention was devoted to the effects of technological developments on the wellbeing and health of employees. Through surveys, researchers identified the main techno-stressors which negatively impacted wellbeing and health [119,171], using a wide range of terms for describing the effects of technological developments on wellbeing and health. For example, Bahamondes-Rosado et al. [104] report on techno-invasion, techno-overload, techno-fatigue, and techno-stress. In turn, ref. [119] understood work–home conflict and overworking as main techno-stressors. In this regard, it is worth highlighting the key roles of taking a systemic approach to balancing work and family [171] and arranging one’s home office to be equipped with all the necessary technology [135].

Remote work is about employing the correct organizational process as well. Literature analysis allows us to conclude which individual characteristics, experiences with previous working modes, peculiarities of occupational positions, and institutional support are key features encouraging or limiting success during remote work. From an organizational perspective, remote working ensured safer spaces during periods with high infection risks through, for example, temporal flexibility and job autonomy [106], split teams, and social distancing [56]. Such activities were necessary to protect workers’ health. At the same time, steps taken to protect workers’ health had additional effects on organizational trust, managerial trust in employees, and changes in workforce management [105,141]. For example, Marzban et al. [105] emphasize positive tendencies such as a high level of trust within organizations and between workers, while Bentham et al. [172] report on support within teams, and Jaiswal and Arun [145] discover sparks of creativity. In parallel, researchers found shortcomings of remote work—chaos in the process and loss of focus [103], prolonged working hours [103,161], reduced face-to-face interactions with colleagues [105], insufficient support from the organization [173], and unclear boundaries between work and home [17,32,33].

According to the literature, organizational effects of remote work affected habitual societal routines relating to healthy or unhealthy habits, self-care, gender roles, and expectations for future housing. Online shopping and consumption of food and drinks clearly mirrored the effects of lockdowns on other daily routines: online shopping increased dramatically [87,170]; food consumption changed, and the kind of food that was consumed varied significantly [67,81,87,174,175]; and alcohol consumption increased in some cases [59,81,176,177,178]. Researchers emphasized better possibilities for self-care [88,153], for example in terms of longer sleeping time, more time spent with family and friends, more time spent on hobbies, eating healthier, and learning new skills. At the same time, a division of domestic work that was grounded in gender roles increased the gender gap and workload, especially for women [156,157,158,167,179].