The Convergence of the Fourth Sector and Generation Z’s Biospheric Values: A Regional Empirical Case Study in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background: Socioecology Principles, FS, and Generation Z

2.1. Socioecology and Entrepreneurship

2.2. The FS Values

2.3. Generation Z Values

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Method

3.2. Sample

3.3. Measures and Instruments

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FS | Fourth Sector |

| TBL | Triple Bottom Line |

| GEN Z | Generation Z |

| AV | Altruistic Values |

| BV | Biospheric Values |

| EFV | Economic–finance Values |

| EOFS | Entrepreneurial Orientation to the FS |

| SEM-PLS | Structural Equation Modeling with Partial Least Squares |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

References

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Carvalho, L.; Rego, C.; Lucas, M.R.; Noronha, A. Social innovation and entrepreneurship in the FS. In Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the FS: Sustainable Best-Practices from Across the World; Sánchez-Hernández, M.I., Carvalho, L., Rego, C., Lucas, M.R., Noronha, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Carvalho, L.; Rego, C.; Lucas, M.R.; Noronha, A. The FS: The future of business, for a better future. In Entrepreneurship in the FS: Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Sustainable Business Models; Sánchez-Hernández, M.I., Carvalho, L., Rego, C., Lucas, M.R., Noronha, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rask, M.; Puustinen, A.; Raisio, H. Understanding the Emerging FS and Its Governance Implications. Scand. J. Public Adm. 2020, 24, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.R.; Braga, V.; Sánchez-Hernández, M.; Gomes, J. Framing the FS—Dystopia or future contours? Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2024, 21, 887–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebiyi, O.; Adeoti, M.; Mupa, M.N. The use of employee ownership structures as strategies for the resilience of smaller entities in the US. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2025, 14, 1002–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClean, S.; Ismail, S.; Bird, E. Community business impacts on health and well-being: A systematic review of the evidence. Soc. Enterp. J. 2021, 17, 459–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narmania, D. Efficient management of municipal enterprises. Eur. J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2018, 3, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkowiak, P.; Bartkowiak, A.M. Contextual nature of sustainable development in the activity of an enterprise, on the example of a municipal enterprises. J. Water Land Dev. 2021, 51, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I. The one for one movement: The new social business model. In Innovations in Social Marketing and Public Health Communication; Wymer, W., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 321–333. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Castilla-Polo, F. Intellectual capital as a predictor of cooperative prominence through human capital in the Spanish agrifood industry. J. Intellect. Cap. 2021, 22, 1126–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñares-Zegarra, J.M.; Wilson, J.O. Navigating uncertainty: The resilience of third-sector organizations and socially oriented small-and medium-sized enterprises during the COVID-19 pandemic. Financ. Account. Manag. 2024, 40, 282–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdá-Suárez, L.; Espinosa-Cristia, J.; Núñez-Valdés, K.; Núñez-Valdés, G. Detecting Circular Economy Strategies in the FS: Overview of the Chilean Construction Sector as Evidence of a Sustainable Business Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.C. Harnessing Voluntary Work: A FS Approach. Policy Stud. 2002, 23, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosillo, I.; Aretano, R.; Zurlini, G. Socioecological systems. In Encyclopedia of Ecology, 2nd ed.; Fath, B., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 419–425. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L. Impact of firm ESG performance on cost of debt: Insights from the Chinese Bond Market. Macroecon. Financ. Emerg. Mark. Econ. 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Saleh, N.M.; Keliwon, K.B.; Ghazali, A.W. Can Multiple Large Shareholders Mitigate Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Controversies? World 2025, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulewicz-Sas, A.; Kinowska, H.; Zubek, M.; Danilewicz, D. Examining the impacts of environmental, social and governance (ESG) on employee engagement: A study of Generation Z. Cent. Eur. Manag. J. 2025. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.A.; Amran, A.; Sahar, N.E. Assessing the impact of corporate environmental irresponsibility on workplace deviant behavior of generation Z and millennials: A multigroup analysis. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2024, 40, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Luppi, J.L.; Simmons, T.; Tran, B.; Zhang, R. Examining the impacts of ESG on employee retention: A study of generational differences. J. Bus. Manag. 2023, 29, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juma-Michilena, I.-J.; Ruiz-Molina, M.-E.; Gil-Saura, I.; Belda-Miquel, S. Pro-environmental behaviours of Generation Z: A cross-cultural approach. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2024, 21, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragolea, L.-L.; Butnaru, G.I.; Kot, S.; Zamfir, C.G.; Nuţă, A.-C.; Nuţă, F.-M.; Cristea, D.S.; Ştefănică, M. Determining factors in shaping the sustainable behavior of the generation Z consumer. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1096183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; d’Arge, R.; De Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; Robert, V. O’Neill; Paruelo, J.; et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Available online: http://www.millenniumassessment.org/documents/document.356.aspx.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Brown, T.C.; Bergstrom, J.C.; Loomis, J.B. Defining, valuing, and providing ecosystem goods and services. Nat. Resour. J. 2007, 47, 329–376. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Hernandez, M.I.; Maldonado-Briegas, J.J.; Sanguino, R.; Barroso, A.; Barriuso, M.C. Users’ perceptions of local public water and waste services: A case study for sustainable development. Energies 2021, 14, 3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Li, J.; Ma, Q. Integrating green infrastructure, ecosystem services and nature-based solutions for urban sustainability: A comprehensive literature review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 98, 104843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, T.C.; Muhar, A.; Arnberger, A.; Aznar, O.; Boyd, J.W.; Chan, K.M.; Costanza, R.; Elmqvist, T.; Flint, C.G.; Gobster, P.H.; et al. Contributions of cultural services to the ecosystem services agenda. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8812–8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fish, R.; Church, A.; Winter, M. Conceptualising cultural ecosystem services: A novel framework for research and critical engagement. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopittke, P.M.; Menzies, N.W.; Wang, P.; McKenna, B.A.; Lombi, E. Soil and the intensification of agriculture for global food security. Environ. Int. 2019, 132, 105078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Biggs, R.; Norström, A.V.; Reyers, B.; Rockström, J. Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Rubio, A.; Olmos-Martínez, E.; Blázquez, M.C. Socioecology and Biodiversity Conservation. Diversity 2021, 13, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, D.V. Ecological habitus: Toward a better understanding of socioecological relations. Organ. Environ. 2009, 22, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurven, M.D. Broadening horizons: Sample diversity and socioecological theory are essential to the future of psychological science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 11420–11427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neisig, M. The circular economy: Rearranging structural couplings and the paradox of moral-based sustainability-enhancing feedback. Kybernetes 2022, 51, 1896–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skene, K.R.; Oarga-Mulec, A. The circular economy: The butterfly diagram, systems theory and the economic pluriverse. Circ. Econ. Appl. Sch. J. Circ. Econ. 2024, 2, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Olmos-Martínez, E.; Romero-Schmidt, H.L.; Blázquez, M.D.C.; Arias-González, C.; Ortega-Rubio, A. Human communities in protected natural areas and biodiversity conservation. Diversity 2022, 14, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calicioglu, Ö. Linking bioeconomy with sustainable development goals: Identifying and monitoring socio-ecological opportunities and challenges of bioeconomy. In Biodiversity and Bioeconomy; Singh, K., Ribeiro, M.C., Calicioglu, Ö., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dyck, B.; Silvestre, B.S. Enhancing socio-ecological value creation through sustainable innovation 2.0: Moving away from maximizing financial value capture. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 1593–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentoni, D.; Pinkse, J.; Lubberink, R. Linking Sustainable Business Models to Socio-Ecological Resilience Through Cross-Sector Partnerships: A Complex Adaptive Systems View. Bus. Soc. 2021, 60, 1216–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, V.; Ferreira, M.; Braga, V. The role of the FS in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Strateg. Change 2021, 30, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, N.; Hoffman, A.J. Hybrid organizations: The next chapter of sustainable business. Organ. Dyn. 2012, 41, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, B.; Haugh, H.; Lyon, F. Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabazo-Martín, A.E.; Rodríguez-Rivero, E.J. Reflections on Hybrid Corporations, Social Entrepreneur, and New Generations. In Entrepreneurship in the FS: Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Sustainable Business Models; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2012; pp. 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, B.; Henning, N.; Reyna, E.; Wang, D.; Welch, M.; Hoffman, A.J. Hybrid Organizations: New Business Models for Environmental Leadership; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, F.G.; Varon Garrido, M.A. Can profit and sustainability goals co-exist? New business models for hybrid firms. J. Bus. Strategy 2017, 38, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luttrell, R.; McGrath, K. Gen Z: The Superhero Generation; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, A. Generation Z: Technology and social interest. J. Individ. Psychol. 2015, 71, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. Gen Z and Millennial Survey. 2024. Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/global/en/issues/work/content/genz-millennialsurvey.html (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Bhalla, R.; Tiwari, P.; Chowdhary, N. Digital natives leading the world: Paragons and values of Generation Z. In Generation Z Marketing and Management in Tourism and Hospitality: The Future of the Industry; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Prensky, M. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 1. Horizon 2001, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.C.; Perez, J. Unraveling the digital literacy paradox: How higher education fails at the fourth literacy. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2014, 11, 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, L.; Button, D.; Brommeyer, M. Challenging the Myth of the Digital Native: A Narrative Review. Nurs. Rep. 2023, 13, 573–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Ling, R. Drivers of social media fatigue: A systematic review. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 64, 101696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakobus, I.K.; Suat, H.; Kurniawati, K.; Zulham, Z.; Pannyiwi, R.; Anurogo, D. The Use Social Media’s on Adolescents’ Mental Health. Int. J. Health Sci. 2023, 1, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Ngoc, T.; Viet Dung, M.; Rowley, C.; Pejić Bach, M. Generation Z job seekers’ expectations and their job pursuit intention: Evidence from transition and emerging economy. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2022, 14, 18479790221112548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaros, K.K. Gen Z Employee Adaptive Performance: The Role of Inclusive Leadership and Workplace Happiness. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priporas, C.V.; Stylos, N.; Kamenidou, I.E. City image, city brand personality and generation Z residents’ life satisfaction under economic crisis: Predictors of city-related social media engagement. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 119, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, R.; Ogilvie, S.; Shaw, J.; Woodhead, L. Gen Z, Explained: The Art of Living in a Digital Age; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jasin, D.; Hansaram, R.K.; Chong, K.L. Social Entrepreneurship in the Eyes of Generation Z: An Intentional Perspective. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2024, 14, 2180–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chillakuri, B. Understanding Generation Z expectations for effective onboarding. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2020, 33, 1277–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, A.I. The future of employment: How Generation Z is reshaping entrepreneurship through education? Edu Spectr. J. Multidimens. Educ. 2024, 1, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barati, M. Casual Social Media Use among the Youth: Effects on Online and Offline Political Participation. JeDEM-EJournal EDemocracy Open Gov. 2023, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloni, M.; Hiatt, M.S.; Campbell, S. Understanding the work values of Gen Z business students. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2019, 17, 100320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Kalof, L. Value orientations, gender, and environmental concern. Environ. Behav. 1993, 25, 322–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C.; Kalof, L.; Dietz, T.; Guagnano, G.A. Values, beliefs, and proenvironmental action: Attitude formation toward emergent attitude objects. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 25, 1611–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreg, S.; Katz-Gerro, T. Predicting proenvironmental behavior cross-nationally: Values, the theory of planned behavior, and value-belief-norm theory. Environ. Behav. 2006, 38, 462–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebarajakirthy, C.; Sivapalan, A.; Das, M.; Maseeh, H.I.; Ashaduzzaman, M.; Strong, C.; Sangroya, D. A meta-analytic integration of the theory of planned behavior and the value-belief-norm model to predict green consumption. Eur. J. Mark. 2024, 58, 1141–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negm, E. Recognizing the impact of value-belief-norm theory on pro-environmental behaviors of higher education students: Considering aspects for social-marketing applications. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024, 25, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snelgar, R.S. Egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric environmental concerns: Measurement and structure. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Value orientations and environmental beliefs in five countries—Validity of an instrument to measure egoistic, altruistic and biospheric value orientations. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2007, 38, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.; Steg, L. Value orientations to explain beliefs related to environmental significant behavior: How to measure egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric value orientations. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 330–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarieva, A.M.; Gorshkov, V.G.; Li, B.L. Energy budget of the biosphere and civilization: Rethinking environmental security of global renewable and non-renewable resources. Ecol. Complex. 2008, 5, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. The value basis of environmental concern. J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Czellar, S. Where do biospheric values come from? A connectedness to nature perspective. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 52, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, T.; Steg, L.; Zawadzki, S.J. The value of what others value: When perceived biospheric group values influence individuals’ pro-environmental engagement. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 71, 101470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, P. Influence of Millennials’ eco-literacy and biospheric values on green purchases: The mediating effect of attitude. Public Organ. Rev. 2023, 23, 1195–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, A.; Walia, S.K.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Gen Z and the flight shame movement: Examining the intersection of emotions, biospheric values, and environmental travel behaviour in an Eastern society. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 1621–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, S.M.; Rūtelionė, A.; Bhutto, M.Y. The Role of Environmental Values, Environmental Self-Identity, and Attitude in Generation Z’s Purchase Intentions for Organic Food. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 2024, 80, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robina-Ramírez, R.; Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Jiménez-Naranjo, H.V.; Díaz-Caro, C. The challenge of greening religious schools by improving the environmental competencies of teachers. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xing, J. The impact of social media information sharing on the green purchase intention among generation Z. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, C. Sowing the seeds: Education for sustainability within the early years curriculum. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 18, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selly, P.B. Early Childhood Activities for a Greener Earth; Redleaf Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Weldemariam, K.; Boyd, D.; Hirst, N.; Sageidet, B.M.; Browder, J.K.; Grogan, L.; Hughes, F. A critical analysis of concepts associated with sustainability in early childhood curriculum frameworks across five national contexts. Int. J. Early Child. 2017, 49, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, S.F. Harmony of Nature and Culture: Symbolism and Environmental Education in Ritual. J. Contemp. Ritual. Tradit. 2023, 1, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Berthold, A. The lasting effect of the Romantic view of nature: How it influences perceptions of risk and the support of symbolic actions against climate change. Risk Anal. 2024, 1–11, online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fike, K.J.; Mattis, J.S.; Nickodem, K.; Guillaume, C. Black adolescent altruism: Exploring the role of racial discrimination and empathy. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2023, 150, 106990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.F.; Thompson, J. Fickle Prosociality: How Violence against LGBTQ+ People Motivates Prosocial Mass Attitudes toward LGBTQ+ Group Members. In American Political Science Review; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2024; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yarris, K.E.; Garcia-Millan, B.; Schmidt-Murillo, K. Motivations to help: Local volunteer humanitarians in US refugee resettlement. J. Refug. Stud. 2020, 33, 437–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammaerts, B. The abnormalisation of social justice: The ‘anti-woke culture war’discourse in the UK. Discourse Soc. 2022, 33, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietropaoli, M. New Aspects of Well-being in the Crisis Era: Emotions, Generations, Anxieties, and Work. PuntOorg Int. J. 2024, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyrou, S. Children as future-makers. Childhood 2020, 27, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naha, D. Redefining Realities: The Impact of Digital Media on Social Awareness. In Knowledge, Society and Sustainability: Multidisciplinary Approaches; Ghosh, A., Ed.; Shashwat Publication: Bilaspur, India, 2025; pp. 80–91. [Google Scholar]

- Cassar, G. Money, money, money? A longitudinal investigation of entrepreneur career reasons, growth preferences and achieved growth. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2007, 19, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruett, M.; Shinnar, R.; Toney, B.; Llopis, F.; Fox, J. Explaining entrepreneurial intentions of university students: A cross-cultural study. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2009, 15, 571–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalitanyi, V.; Bbenkele, E. Assessing the role of socio-economic values on entrepreneurial intentions among university students in Cape Town. South Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2017, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakara, W.A.; Laouiti, R.; Chavez, R.; Gharbi, S. An economic view of entrepreneurial intention. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 1807–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS 4. Bönningstedt: SmartPLS 2024. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Moleiro Martins, J.; Nuno Mata, M.; Naz, S.; Akhtar, S.; Abreu, A. Linking entrepreneurial orientation with innovation performance in SMEs; the role of organizational commitment and transformational leadership using smart PLS-SEM. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, J.; Jin, Y.; Wang, T.; Lin, C.L.; Xu, D. Factors influencing entrepreneurial intention of university students in China: Integrating the perceived university support and theory of planned behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Rosa, I.; Gutiérrez-Taño, D.; García-Rodríguez, F.J. Social entrepreneurial intention and the impact of COVID-19 pandemic: A structural model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Aguilar-Yuste, M.; Maldonado-Briegas, J.J.; Seco-González, J.; Barriuso-Iglesias, C.; Galán-Ladero, M.M. Modelling municipal Social Responsibility: A pilot study in the Region of Extremadura (Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 6887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I. Strengthening Resilience: Social Responsibility and Citizen Participation in Local Governance. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelario-Moreno, C.; Sánchez-Hernández, M.I. Redefining rural entrepreneurship: The impact of business ecosystems on the success of rural businesses in Extremadura, Spain. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2024, 20, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Molina, F.; Carrapiso-Luceño, E.; Sánchez-Hernández, M.I. The FS and the 2030 Strategy on Green and Circular Economy in the Region of Extremadura. In Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the FS: Sustainable Best-Practices from Across the World; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 283–297. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, D.L.; Lane, M.D. Individual entrepreneurial orientation: Development of a measurement instrument. Educ. Train. 2012, 54, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Breier, M.; Jones, P.; Hughes, M. Individual entrepreneurial orientation and intrapreneurship in the public sector. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 1247–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

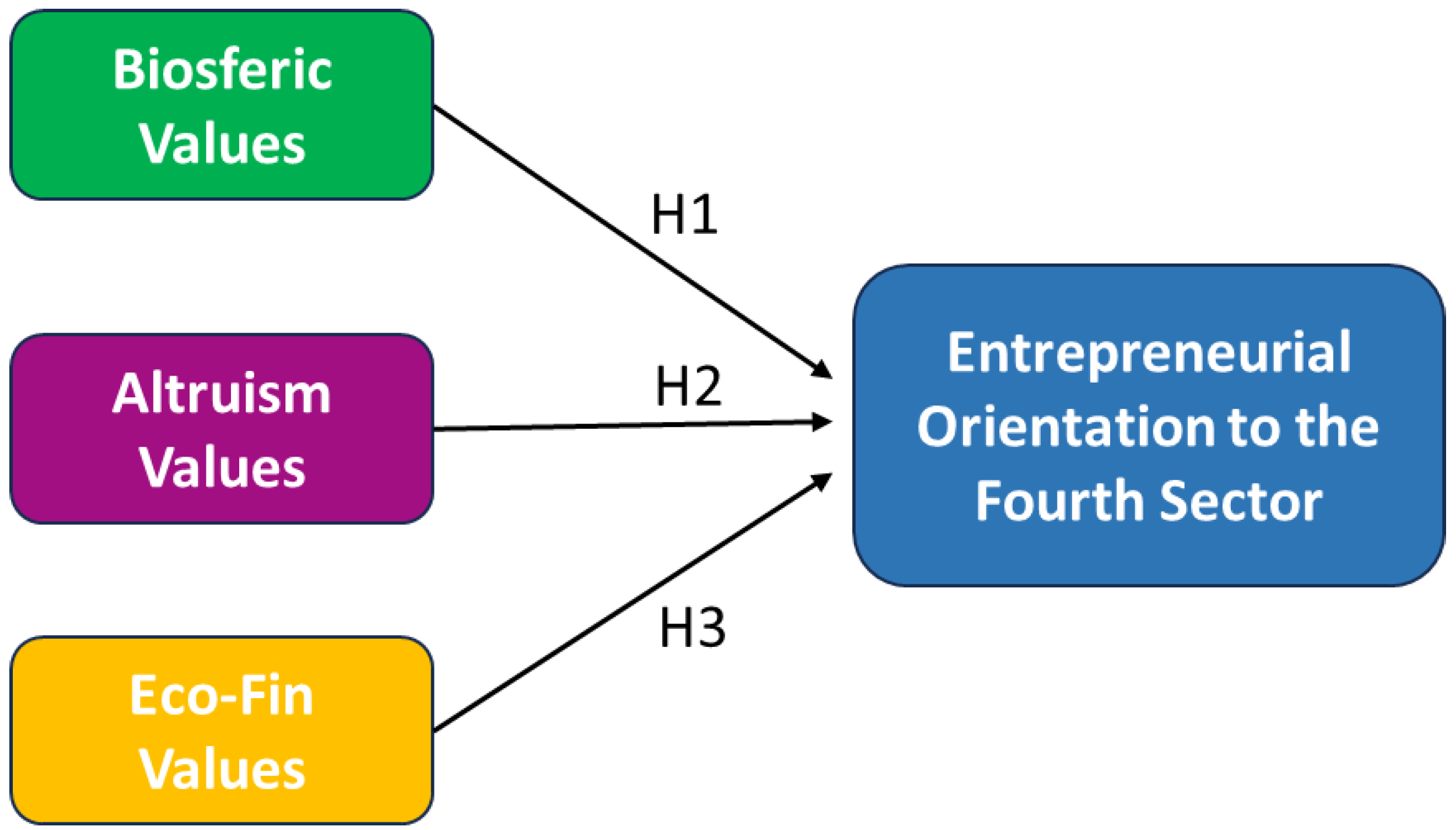

| Construct | Definition | Theoretical Basis | Link to the FS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biospheric Values | Concern for the biosphere and ecosystems | Value–Belief–Norm Theory and Socioecology | Initiatives addressing environmental challenges through profitable approaches align with the FS model |

| Altruistic Values | Concern for the welfare of others and social justice | Value–Belief–Norm Theory | Initiatives targeting social welfare and justice through financially sustainable models align with the FS |

| Economic–Financial Values | Emphasis on profit, financial sustainability, and business viability | TBL and Entrepreneurial Theory | Social and environmental initiatives that ensure profit and financial sustainability are integral to the FS |

| Construct | Items (Internal Code) | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Biospheric Values | It is important to prevent pollution (BV1) It is important to protect the environment (BV2) It is important to respect nature (BV3) It is important to live in harmony with nature (BV4) | Groot and Steg [73,74] |

| Altruistic Values | It is important that everyone has the same opportunities (AV1) It is important to care for those who are in worse situations (AV2) It is important that all people are treated fairly (AV3) It is important that there are no conflicts or wars (AV4) It is important to be useful and help others (AV5) | |

| Economic and Financial Values | I believe that generating profits is the main reason to start a business (EFV1) I support the sale of goods and services for profit (EFV2) I agree that companies should seek to maximize their economic profits (EFV3) I believe it is acceptable for companies to aim at maximizing shareholder wealth (EFV4) I believe that social organizations should survive through their earnings (EFV5) I agree that companies’ profits should be the means to achieve social goals (EFV6) | Bolton and Lane [109] and Kraus et al. [110] |

| Entrepreneurship orientation in the FS | I agree that solving social (and/or environmental) problems can be a way to make money (EOFS1) There is nothing wrong with identifying new business opportunities for social (and/or environmental) change (EOFS2) It is acceptable to pursue economic profit by addressing people’s (and/or environmental) problems (EOFS3) I believe it is possible to achieve economic profit for the company and benefits for society (and/or the environment) at the same time (EOFS4) It is ethical to make money by doing good (EOFS5) | Sánchez-Hernandez et al. [1,2] |

| Constructs | Cronbach’s Alfa | rho_A | Composite Reliability | AVE | Fornell–Larcker Criterion (Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BV | AV | EFV | EOFS | |||||

| Biospheric Values (BV) | 0.884 | 0.884 | 0.892 | 0.921 | 0.863 | |||

| Altruistic Values (AV) | 0.892 | 0.942 | 0.918 | 0.693 | 0.725 (0.809) | 0.832 | ||

| Economic–finance Values (EFV) | 0.778 | 0.793 | 0.846 | 0.525 | 0.292 (0.327) | 0.293 (0.317) | 0.724 | |

| Entrepreneurial orientation to the FS (EOFS) | 0.824 | 0.830 | 0.875 | 0.584 | 0.406 (0.426) | 0.491 (0.539) | 0.589 | 0.764 |

| Hypotheses | β | Confidence Intervals | Significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower CI (2.5%) | Upper CI (97.5%) | Standard Deviation | t Statistic | p-Value | ||

| H1: BV → EOFS | 0.333 | 0.165 | 0.529 | 0.095 | 3.507 | 0.000 *** |

| H2: AV → EOFS | 0.022 | −0.169 | 0.206 | 0.099 | 0.224 | 0.823 |

| H3: EFV → EOFS | 0.485 | 0.357 | 0.603 | 0.063 | 7.661 | 0.000 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Rabazo-Martín, A.; Rodriguez-Rivero, E.; Guerrero-Cáceres, J.M. The Convergence of the Fourth Sector and Generation Z’s Biospheric Values: A Regional Empirical Case Study in Spain. World 2025, 6, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020083

Sánchez-Hernández MI, Rabazo-Martín A, Rodriguez-Rivero E, Guerrero-Cáceres JM. The Convergence of the Fourth Sector and Generation Z’s Biospheric Values: A Regional Empirical Case Study in Spain. World. 2025; 6(2):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020083

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Hernández, María Isabel, Aurora Rabazo-Martín, Edilberto Rodriguez-Rivero, and José María Guerrero-Cáceres. 2025. "The Convergence of the Fourth Sector and Generation Z’s Biospheric Values: A Regional Empirical Case Study in Spain" World 6, no. 2: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020083

APA StyleSánchez-Hernández, M. I., Rabazo-Martín, A., Rodriguez-Rivero, E., & Guerrero-Cáceres, J. M. (2025). The Convergence of the Fourth Sector and Generation Z’s Biospheric Values: A Regional Empirical Case Study in Spain. World, 6(2), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020083